- Page 1 and 2: United States Department of Agricul

- Page 4 and 5: Cover photo The scientific names fo

- Page 6 and 7: Rebecca G. Nisley editorial coordin

- Page 8: Introduction v How to Use This Book

- Page 11 and 12: ecame the primary nomenclature reso

- Page 13 and 14: Chapter 1 Seed Biology Franklin T.

- Page 15 and 16: Libocedrus (see Calocedrus) 313 Lig

- Page 17 and 18: Introduction 4 Flowering Plants 4 R

- Page 19 and 20: varied among species, ranging from

- Page 21: There are other effects of moisture

- Page 25 and 26: Pollen grains of trees are extremel

- Page 27 and 28: common in forest species but has be

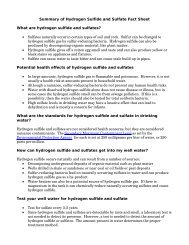

- Page 29 and 30: Table 2—Chapter 1, Seed Biology:

- Page 31 and 32: Figure 6—Chapter 1, Seed Biology:

- Page 33 and 34: Figure 9—Chapter 1, Seed Biology:

- Page 35 and 36: D. Don), ponderosa, digger (P. sabi

- Page 37 and 38: significant. Fowells and Schubert (

- Page 39 and 40: closed or only partly open, and see

- Page 41 and 42: seedcoats (Sandif 1988; Stubsgaard

- Page 43 and 44: Table 10—Chapter 1, Seed Biology:

- Page 45 and 46: (Bouvier-Durand and others 1984; Sa

- Page 47 and 48: Carl CM, Snow AG. 1971. Maturation

- Page 49 and 50: Martin GC, Dennis FG Jr, MacMillan

- Page 51 and 52: Vázquez-Yanes C, Orozco-Segovia A,

- Page 53 and 54: Chapter 2 Genetic Improvement of Fo

- Page 55 and 56: also replicated on different sites

- Page 57 and 58: The Genetic Code The physical basis

- Page 59 and 60: have been operating for a number of

- Page 61 and 62: Figure 3—Chapter 2, Genetic Impro

- Page 63 and 64: dictates locations that cause a maj

- Page 65 and 66: In the Western United States, seed

- Page 67 and 68: The Pacific Northwest Tree improvem

- Page 69 and 70: Abbott JE. 1974. Introgressive hybr

- Page 71 and 72: Introduction 58 Harvesting 58 Plann

- Page 73 and 74:

Figure 1—Chapter 3, Seed Harvesti

- Page 75 and 76:

drop. This delay provides some marg

- Page 77 and 78:

Seed Acquisition Seed harvesting ca

- Page 79 and 80:

appearance could be due to the gene

- Page 81 and 82:

Those seeds that can be dried are r

- Page 83 and 84:

Figure 14—Chapter 3, Seed Harvest

- Page 85 and 86:

tightly they press against the shel

- Page 87 and 88:

However, before the wing is removed

- Page 89 and 90:

machine is determined by the speed

- Page 91 and 92:

large amount of pitch. The pitch pa

- Page 93 and 94:

damaged seedcoats. The seeds are pl

- Page 95 and 96:

Figure 40—Chapter 3, Seed Harvest

- Page 97 and 98:

Aldous JR. 1972. Nursery practice.

- Page 99 and 100:

Introduction 86 Factors Affecting L

- Page 101 and 102:

Table 1—Chapter 4, Storage of See

- Page 103 and 104:

drates and very little lipid. Even

- Page 105 and 106:

Table 7—Chapter 4, Storage of See

- Page 107 and 108:

Figure 4—Chapter 4, Storage of Se

- Page 109 and 110:

Barnett JP,Vozzo JA. 1985. Viabilit

- Page 111 and 112:

Chapter 5 Seed Testing Robert P. Ka

- Page 113 and 114:

Figure 1—Chapter 5, Seed Testing:

- Page 115 and 116:

gain or lose moisture in exchange w

- Page 117 and 118:

lot. “Inert matter” is all othe

- Page 119 and 120:

The germination test is conducted o

- Page 121 and 122:

A species that does not require pre

- Page 123 and 124:

daily germination increases with ea

- Page 125 and 126:

X-Radiography X-radiography is very

- Page 127 and 128:

seedling in a cell drops to .01, bu

- Page 129 and 130:

Anderson HW, Wilson BC. 1966. Impro

- Page 131 and 132:

Introduction 118 Certification in A

- Page 133 and 134:

Figure 2—Chapter 6, Certification

- Page 135 and 136:

(which varied only slightly from th

- Page 137 and 138:

seeds must receive a derogation (sp

- Page 139 and 140:

Introduction 126 Terminology 126 Th

- Page 141 and 142:

Figure 2—Chapter 7, Nursery Pract

- Page 143 and 144:

Genetic Considerations Most seedlin

- Page 145 and 146:

Table 1—Chapter 7, Nursery Practi

- Page 147 and 148:

wheel with clips to place the trans

- Page 149 and 150:

Soil Management and Seedbed Prepara

- Page 151 and 152:

Bareroot nurseries apply mineral nu

- Page 153 and 154:

Figure 14—Chapter 7, Nursery Prac

- Page 155 and 156:

1 seed per cavity. Although expensi

- Page 157 and 158:

Figure 18—Chapter 7, Nursery Prac

- Page 159 and 160:

Figure 20—Chapter 7, Nursery Prac

- Page 161 and 162:

Part II Specific Handling Methods a

- Page 163 and 164:

A Table 1—Abies, fir: nomenclatur

- Page 165 and 166:

A Table 1—Abies, fir: nomenclatur

- Page 167 and 168:

A 9 species—Pacific silver, balsa

- Page 169 and 170:

A Table 2—Abies, fir: schematic o

- Page 171 and 172:

A their validity is questionable (F

- Page 173 and 174:

A Guatemala have been reported (Agu

- Page 175 and 176:

A Thinning promoted fruiting in 150

- Page 177 and 178:

A Figure 5—Abies, fir: mature see

- Page 179 and 180:

A ber on the south side of the tree

- Page 181 and 182:

A Table 4—Abies, fir: insects aff

- Page 183 and 184:

A vigor (Laacke 1990a&b) and produc

- Page 185 and 186:

A detachment indicates that they ha

- Page 187 and 188:

A need turning at least once each d

- Page 189 and 190:

A The IDS (incubating-drying-separa

- Page 191 and 192:

A Table 9—Abies, fir: experiences

- Page 193 and 194:

A Table 10—Abies, fir: nursery pr

- Page 195 and 196:

A dried to 35% and refrigerated for

- Page 197 and 198:

A 1988). Tetrazolium test results o

- Page 199 and 200:

A 1989). Pesticide use changes over

- Page 201 and 202:

A Bergsten U. 1993. Removal of dead

- Page 203 and 204:

A Franklin JF. 1965. An exploratory

- Page 205 and 206:

A Irmak A. 1961. The seed-fall of f

- Page 207 and 208:

A MacLean DW. 1960. Some aspects of

- Page 209 and 210:

A Roe EI. 1948b. Balsam fir seed: i

- Page 211 and 212:

A Tulstrup NP. 1952. Skovfrø: nogl

- Page 213 and 214:

A Table 1—Acacia, acacia: nomencl

- Page 215 and 216:

A Table 4—Acacia, accacia: preger

- Page 217 and 218:

A Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 219 and 220:

A found to be highly skewed to male

- Page 221 and 222:

A stands due to tree distribution a

- Page 223 and 224:

A the forest floor for at least 3 t

- Page 225 and 226:

A Table 5—Acer, maple: warm and c

- Page 227 and 228:

A Sometimes maple seedlings are lar

- Page 229 and 230:

A Van Gelderen DM, De Jong PC, Oter

- Page 231 and 232:

A Nursery practice. Although there

- Page 233 and 234:

A flower spikes are 15 to 20 cm tal

- Page 235 and 236:

A tures at 5 °C for about 120 days

- Page 237 and 238:

A Synonyms. Toxicodendron altissimu

- Page 239 and 240:

A Feret PP. 1985. Ailanthus: variat

- Page 241 and 242:

A Table 2—Albizia, albizia: pheno

- Page 243 and 244:

A Synonyms. Aleurites javanica Gand

- Page 245 and 246:

A Growth habit and occurrence. Alde

- Page 247 and 248:

A Table 1—Alnus, alder: nomenclat

- Page 249 and 250:

A Figure 2—Alnus, alder: nuts (se

- Page 251 and 252:

A Table 5—Alnus, alder: stratific

- Page 253 and 254:

A and early growth in the nursery (

- Page 255 and 256:

A Pojar J, MacKinnon A, comps. & ed

- Page 257 and 258:

A als by Kay and others (1988) refe

- Page 259 and 260:

A Table 2—Amelanchier, serviceber

- Page 261 and 262:

A tions (Acharya and others 1989).

- Page 263 and 264:

A Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 265 and 266:

A Figure 2—Amorpha canescens, lea

- Page 267 and 268:

A be taken when lifting, as the roo

- Page 269 and 270:

A 1981). A distinguishing character

- Page 271 and 272:

A Figure 4—Aralia nudicaulis, wil

- Page 273 and 274:

A to 27 years old and are about 20

- Page 275 and 276:

A should be treated with a fungicid

- Page 277 and 278:

A Figure 2—Arbutus menziesii, Pac

- Page 279 and 280:

A Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 281 and 282:

A may be checked in the field by cu

- Page 283 and 284:

A Keeley JE. 1995. Seed germination

- Page 285 and 286:

A Table 2—Aronia, chokeberry: phe

- Page 287 and 288:

A Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 289 and 290:

A the exterior of the pericarp may

- Page 291 and 292:

A others 1959; Wilson 1982) probabl

- Page 293 and 294:

A Wagstaff FJ, Welch BL. 1991. Seed

- Page 295 and 296:

A soundness are as follows (Bonner

- Page 297 and 298:

A Table 1—Atriplex, saltbush: eco

- Page 299 and 300:

A Figure 2—Atriplex semibaccata,A

- Page 301 and 302:

A ole walls may also be weakened by

- Page 303 and 304:

A Gerard JB. 1978. Factors affectin

- Page 305 and 306:

B Table 1—Baccharis, baccharis: n

- Page 307 and 308:

B Table 3 —Baccharis, baccharis:

- Page 309 and 310:

B Table 2—Bauhinia, bauhinia: flo

- Page 311 and 312:

B Berberidaceae—Barberry family G

- Page 313 and 314:

B Table 2—Berberis, barberry: phe

- Page 315 and 316:

B Ahrendt T. 1961. Berberis and Mah

- Page 317 and 318:

B Table 1—Betula, birch: nomencla

- Page 319 and 320:

B Figure 1—Betula, birch: ripe fe

- Page 321 and 322:

B Table 5—Betula, birch: germinat

- Page 323 and 324:

B References Ahlgren CE.1957. Pheno

- Page 325 and 326:

C seeds sink in water, and the pulp

- Page 327 and 328:

C the winter and early spring...”

- Page 329 and 330:

C Reported averages representing co

- Page 331 and 332:

C McDonald PM. 1992. Estimating see

- Page 333 and 334:

C 10 °C is recommended for quick a

- Page 335 and 336:

C Figure 3—Caragana arborsecens,

- Page 337 and 338:

C Cactaceae Cactus family Carnegiea

- Page 339 and 340:

C Growth habit. Carpenteria (bush-a

- Page 341 and 342:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 343 and 344:

C Table 2—Carpinus, carpinus: phe

- Page 345 and 346:

C Allen DH. 1995. Personal communic

- Page 347 and 348:

C Table 2—Carya, hickory: phenolo

- Page 349 and 350:

C imbibed nuts in plastic bags with

- Page 351 and 352:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 353 and 354:

C is especially important if the we

- Page 355 and 356:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 357 and 358:

C Nursery practice. In the nursery,

- Page 359 and 360:

C Figure 1—Catalpa bignonioides,

- Page 361 and 362:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 363 and 364:

C Figure 1—Ceanothus, ceanothus:

- Page 365 and 366:

C Table 3—Ceanothus, ceanothus: t

- Page 367 and 368:

C stimulate germination. For wester

- Page 369 and 370:

C Poth M, Barro SC. 1986. On the th

- Page 371 and 372:

C seeds (table 2) (Dirr 1990; Farjo

- Page 373 and 374:

C temperatures of 20 °C (night) an

- Page 375 and 376:

C Hartmann HT, Kester DE, Davies FT

- Page 377 and 378:

C Extraction and storage of seeds.

- Page 379 and 380:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 381 and 382:

C Table 3—Celtis, hackberry: heig

- Page 383 and 384:

C Germination tests. Buttonbush see

- Page 385 and 386:

C Figure 1—Ceratonia siliqua, car

- Page 387 and 388:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 389 and 390:

C Figure 1—Cercis canadensis, eas

- Page 391 and 392:

C whether to dip the seeds for 15 o

- Page 393 and 394:

C Jones RO, Geneve RL. 1995. Seedco

- Page 395 and 396:

C ledifolius is more shrubby (or le

- Page 397 and 398:

C Nursery and field practice. Curll

- Page 399 and 400:

C Adams RS. 1969. How to cure mount

- Page 401 and 402:

C Rosoideae). McArthur and Sanderso

- Page 403 and 404:

C Kirkwood JE. 1930. Northern Rocky

- Page 405 and 406:

C Table 2—Chamaecyparis, white-ce

- Page 407 and 408:

C Table 4—Chamaecyparis, white-ce

- Page 409 and 410:

C 396 • Woody Plant Seed Manual B

- Page 411 and 412:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 413 and 414:

C zomes. Cultivation attempts often

- Page 415 and 416:

C Figure 2—Chionanthus virginicus

- Page 417 and 418:

C Synonyms. The 2 species of Chryso

- Page 419 and 420:

C Figure 3—Chrysolepsis, chinquap

- Page 421 and 422:

C Table 1—Chrysothamnus, rabbitbr

- Page 423 and 424:

C Table 2—Chrysothamnus, rabbitbr

- Page 425 and 426:

C Anderson LC. 1986. An overview of

- Page 427 and 428:

C Figure 1—Cladrastis kentukea, y

- Page 429 and 430:

C Dates of flowering and fruiting a

- Page 431 and 432:

C Table 5—Clematis, clematis: ger

- Page 433 and 434:

C have been observed (Bir 1992b). T

- Page 435 and 436:

C 422 • Woody Plant Seed Manual R

- Page 437 and 438:

C Figure 3—Coleogyne ramosissima,

- Page 439 and 440:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 441 and 442:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 443 and 444:

C Table 2—Cornus, dogwood: phenol

- Page 445 and 446:

C and sow them in the spring (Goodw

- Page 447 and 448:

C Other common names. Filbert, haze

- Page 449 and 450:

C carried out on the nature of dorm

- Page 451 and 452:

C 438 • Woody Plant Seed Manual A

- Page 453 and 454:

C Table 2—Cotinus, smoketree: see

- Page 455 and 456:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 457 and 458:

C Table 2—Cotoneaster, cotoneaste

- Page 459 and 460:

C (Shaw and others 2004). Germinati

- Page 461 and 462:

C Table 1—Crataegus, hawthorn: no

- Page 463 and 464:

C edible fruits in Asia, Central Am

- Page 465 and 466:

C Figure 1—Crataegus, hawthorn: c

- Page 467 and 468:

C recommended that if controlled se

- Page 469 and 470:

C Flint HL. 1997. Landscape plants

- Page 471 and 472:

C Figure 2—Cryptomeria japonica,

- Page 473 and 474:

C Table 1—Cupressus, cypress: nom

- Page 475 and 476:

C Table 3—Cupressus, cypress: see

- Page 477 and 478:

C Table 4—Cupressus, cypress: ger

- Page 479 and 480:

C Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 481 and 482:

D Fabaceae—Pea family Delonix reg

- Page 483 and 484:

D Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 485 and 486:

D Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 487 and 488:

D screen cleaner to remove trash an

- Page 489 and 490:

D 476 • Woody Plant Seed Manual T

- Page 491 and 492:

D anthers still contained pollen in

- Page 493 and 494:

D Figure 6—Dirca palustris, easte

- Page 495 and 496:

E Fabaceae—Pea family Ebenopsis e

- Page 497 and 498:

E Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 499 and 500:

E Table 3—Elaeagnus, elaeagnus: h

- Page 501 and 502:

E Other common names. brittlebush,

- Page 503 and 504:

E Fabaceae—Pea family Enterolobiu

- Page 505 and 506:

E Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 507 and 508:

E Figure 2—Ephedra viridis,Torrey

- Page 509 and 510:

E Germination tests. Germination is

- Page 511 and 512:

E Germination. Parish goldenweed se

- Page 513 and 514:

E Table 1— Eriogonum, wild-buckwh

- Page 515 and 516:

E Table 2—Eriogonum, wild-buckwhe

- Page 517 and 518:

E Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 519 and 520:

E fall; and tallowwood eucalyptus i

- Page 521 and 522:

E Table 4—Eucalyptus, eucalyptus:

- Page 523 and 524:

E Table 7—Eucalyptus, eucalyptus:

- Page 525 and 526:

E Geary TF, Meskimen GF, Franklin E

- Page 527 and 528:

E Table 2— Euonymus, euonymus: he

- Page 529 and 530:

E Figure 3—Euonymus, euonymus: se

- Page 531 and 532:

E Table 8—Euonymus, euonymus: ger

- Page 533 and 534:

F Fagaceae—Beech family Fagus L.

- Page 535 and 536:

F Table 3—Fagus, beech: height, s

- Page 537 and 538:

F Ahuja MR. 1986. Short note: stora

- Page 539 and 540:

F Figure 2—Fallugia paradoxa, Apa

- Page 541 and 542:

F Synonym. Flindersia chatawaiana F

- Page 543 and 544:

F 530 • Woody Plant Seed Manual R

- Page 545 and 546:

F Table 1—Frangula, buckthorn: no

- Page 547 and 548:

F Arno SF, Hammerly RP. 1977. North

- Page 549 and 550:

F Figure 2—Franklinia alatamaha,

- Page 551 and 552:

F Deusen and Cunningham 1982), and

- Page 553 and 554:

F Table 4—Fraxinus, ash: seed yie

- Page 555 and 556:

F Table 6—Fraxinus, ash: germinat

- Page 557 and 558:

F Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 559 and 560:

F because the period of germination

- Page 561 and 562:

G Table 1—Garrya, silktassel: occ

- Page 563 and 564:

G Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 565 and 566:

G Table 2—Gaultheria, wintergreen

- Page 567 and 568:

G stratified and sown in the spring

- Page 569 and 570:

G McMinn HE. 1970. An illustrated m

- Page 571 and 572:

G Germination. Black huckleberry se

- Page 573 and 574:

G Figure 2—Ginkgo biloba, ginkgo:

- Page 575 and 576:

G Growth habit and uses. There are

- Page 577 and 578:

G the acid treatment has been much

- Page 579 and 580:

G Figure 3—Gordonia lasianthus, l

- Page 581 and 582:

G consists of a single pistil enclo

- Page 583 and 584:

G Wallace and Romney 1972; Wood and

- Page 585 and 586:

G Everett RL,Tueller PT, Davis JB,

- Page 587 and 588:

G Figure 1—Grevillea robusta, sil

- Page 589 and 590:

G Figure 2—Gutierrezia sarothrae,

- Page 591 and 592:

G Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 593 and 594:

H Other common names. opossum-wood,

- Page 595 and 596:

H Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 597 and 598:

H Nursery practice. Witch-hazel see

- Page 599 and 600:

H Figure 2—Heteromeles arbutifoli

- Page 601 and 602:

H Other common names. Sandthorn, sw

- Page 603 and 604:

H Papp L. 1982. The importance of v

- Page 605 and 606:

H (Stark 1966; Sutton and Johnson 1

- Page 607 and 608:

H Creambush ocean-spray can be esta

- Page 609 and 610:

H Figure 2—Hymenaea courbaril, co

- Page 611 and 612:

I Table 2—Ilex, holly: phenology

- Page 613 and 614:

I Afanasiev M. 1942. Propagation of

- Page 615 and 616:

J cultural varieties of English and

- Page 617 and 618:

J often spread on the ground in the

- Page 619 and 620:

J Beineke WF. 1989. Twenty years of

- Page 621 and 622:

J Table 1—Juniperus, juniper: nom

- Page 623 and 624:

J Table 3—Juniperus, juniper: hei

- Page 625 and 626:

J Nursury practices. Juniper seeds

- Page 627 and 628:

J Johnsen TN Jr, Alexander RA. 1974

- Page 629 and 630:

K (Jaynes 1997). An individual shru

- Page 631 and 632:

K 618 • Woody Plant Seed Manual A

- Page 633 and 634:

K Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 635 and 636:

K temperature and longer in cold st

- Page 637 and 638:

K Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 639 and 640:

K Synonyms. Eurotia lanata (Pursh)

- Page 641 and 642:

K Table 1— Krascheninnikovia lana

- Page 643 and 644:

K Pursh F. 1814. Flora Americae Sep

- Page 645 and 646:

L Figure 1—Laburnum anagyroides,

- Page 647 and 648:

L 634 • Woody Plant Seed Manual L

- Page 649 and 650:

L Pregermination treatments and ger

- Page 651 and 652:

L fall. Branching is usually pyrami

- Page 653 and 654:

L The seed cones and pollen cones u

- Page 655 and 656:

L Atmospheric fluorides can reduce

- Page 657 and 658:

L larch seeds keep well for a year

- Page 659 and 660:

L Table 8—Larix, larch: germinati

- Page 661 and 662:

L Eis S, Craigdallie D. 1983. Larch

- Page 663 and 664:

L Simak M. 1973. Separation of fore

- Page 665 and 666:

L Figure 2—Larrea tridentata, cre

- Page 667 and 668:

L Figure 1—Ledum groenlandiicum,

- Page 669 and 670:

L 1980) ripens seeds a month earlie

- Page 671 and 672:

L Fabaceae—Pea family Leucaena le

- Page 673 and 674:

L Brewbaker JL, Plucknett DL, Gonza

- Page 675 and 676:

L Figure 2—Leucothoe fontanesiana

- Page 677 and 678:

L The privets are valued for landsc

- Page 679 and 680:

L AFA [American Forestry Associatio

- Page 681 and 682:

L Figure 1—Lindera benzoin, commo

- Page 683 and 684:

L 670 • Woody Plant Seed Manual H

- Page 685 and 686:

L Table 1—Liquidambar styraciflua

- Page 687 and 688:

L 674 • Woody Plant Seed Manual M

- Page 689 and 690:

L Table 1—Liriodendron tulipifera

- Page 691 and 692:

L Fagaceae—Beech family Lithocarp

- Page 693 and 694:

L spring. Seeding germinated acorns

- Page 695 and 696:

L Occurrence, growth habit, and use

- Page 697 and 698:

L Table 1—Lonicera, honeysuckle:

- Page 699 and 700:

L Figure 2—Lonicera, honeysuckle:

- Page 701 and 702:

L Bailey LH. 1949. Manual of cultiv

- Page 703 and 704:

L as they have stored well in seale

- Page 705 and 706:

L Figure 1—Lupinus, lupine: seeds

- Page 707 and 708:

L Other common names. matrimony vin

- Page 709 and 710:

L Figure 2—Lycium barbarum, matri

- Page 711 and 712:

M Figure 1—Maclura pomifera, Osag

- Page 713 and 714:

M The genus Magnolia comprises abou

- Page 715 and 716:

M Magnolias have the most primitive

- Page 717 and 718:

M Nursery practice. Sowing seeds in

- Page 719 and 720:

M 706 • Woody Plant Seed Manual B

- Page 721 and 722:

M Figure 2—Mahonia, Oregon-grape:

- Page 723 and 724:

M the distal end, and incubating in

- Page 725 and 726:

M Rosaceae—Rose family Malus Mill

- Page 727 and 728:

M Table 2—Malus, apple: phenology

- Page 729 and 730:

M significant impacts on both the p

- Page 731 and 732:

M Meliaceae—Mahogany family Melia

- Page 733 and 734:

M Menispermaceae—Moonseed family

- Page 735 and 736:

M related sub-shrub, was improved b

- Page 737 and 738:

M ing at room temperature. Tumbling

- Page 739 and 740:

M Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 741 and 742:

M Moraceae—Mulberry family Morus

- Page 743 and 744:

M Figure 2—Morus alba, white mulb

- Page 745 and 746:

M Table 4—Morus, mulberry: seed y

- Page 747 and 748:

M deciduous or evergreen shrubs and

- Page 749 and 750:

M However, germination was reduced

- Page 751 and 752:

N Hydrophyllaceae—Waterleaf famil

- Page 753 and 754:

N Other common names. heavenly-bamb

- Page 755 and 756:

N References Afanasiev M. 1943. Ger

- Page 757 and 758:

N (Adams 1927; Schopmeyer 1974). Co

- Page 759 and 760:

N Figure 1—Nyssa, tupelo: fruits

- Page 761 and 762:

N Figure 4—Nyssa sylvatica, black

- Page 763 and 764:

O Flowering and Fruiting. Anatomica

- Page 765 and 766:

O Abrams L. 1944. Illustrated flora

- Page 767 and 768:

O Figure 1—Olea europaea, olive:

- Page 769 and 770:

O Table 1—Olea europaea, olive: f

- Page 771 and 772:

O counts on 2 samples were 4,400 an

- Page 773 and 774:

O Figure 2—Ostrya virginiana, eas

- Page 775 and 776:

O Figure 1—Oxydendron arboreum, s

- Page 777 and 778:

P Fabaceae—Pea family Paraseriant

- Page 779 and 780:

P Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 781 and 782:

P Figure 2—Parkinsonia aculeata,

- Page 783 and 784:

P Figure 1—Parthenocissus quinque

- Page 785 and 786:

P Other common names. paulownia, em

- Page 787 and 788:

P Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 789 and 790:

P Table 3—Penstemon, penstemon, b

- Page 791 and 792:

P 778 • Woody Plant Seed Manual R

- Page 793 and 794:

P Auger J. 1994. Viability and germ

- Page 795 and 796:

P Figure 3—Persea borbonia, redba

- Page 797 and 798:

P Figure 3—Phellodendron amurense

- Page 799 and 800:

P Growth habit, occurrence, and use

- Page 801 and 802:

P Collection, cleaning, and storage

- Page 803 and 804:

P 790 • Woody Plant Seed Manual R

- Page 805 and 806:

P Figure 2—Physocarpus malvaceus,

- Page 807 and 808:

P Table 1—Picea, spruce: nomencla

- Page 809 and 810:

P (Diebel and Fechner 1988; Fechner

- Page 811 and 812:

P Figure 2—Picea glauca, white sp

- Page 813 and 814:

P Table 3—Picea, spruce: common c

- Page 815 and 816:

P Table 4—Picea, spruce: weight o

- Page 817 and 818:

P emergence rate of white spruce se

- Page 819 and 820:

P Ross SD. 1992. Promotion of flowe

- Page 821 and 822:

P Figure 1—Pieris floribunda, mou

- Page 823 and 824:

P Table 1— Pinus, pine: nomenclat

- Page 825:

P Table 1— Pinus, pine: nomenclat

- Page 828 and 829:

Table 2 —Pinus, pine: mature tree

- Page 830 and 831:

the 2-needle form, var. edulis. Mor

- Page 832 and 833:

Pinus parviflora—Japanese white p

- Page 834 and 835:

Guatemala, the var. chiapensis Mart

- Page 836 and 837:

Table 3—Pinus, pine: phenology of

- Page 838 and 839:

Table 4—Pinus, pine: cone ripenes

- Page 840 and 841:

Figure 2A—Pinus, pine: seeds (alt

- Page 842 and 843:

Table 5—Pinus, pine: specific gra

- Page 844 and 845:

Table 6—Pinus, pine: cone process

- Page 846 and 847:

Table 8—Pinus, pine: cone and see

- Page 848 and 849:

Table 9—Pinus, pine: recommended

- Page 850 and 851:

Table 10—Pinus, pine: seed germin

- Page 852 and 853:

Figure 4—Pinus resinosa, red pine

- Page 854 and 855:

losses to birds and rodents, and th

- Page 856 and 857:

Cocozza MA. 1961. Osservazioni sul

- Page 858 and 859:

Lamb GN. 1915. A calendar of the le

- Page 860 and 861:

Steinhoff RJ. 1964. Taxonomy, nomen

- Page 862 and 863:

Figure 2—Pithecellobium dulce, gu

- Page 864 and 865:

core. The elongated embryo is surro

- Page 866 and 867:

Nursery practice. Sycamores are usu

- Page 868 and 869:

tained for at least 5 years. For lo

- Page 870 and 871:

Table 1—Populus, poplar, cottonwo

- Page 872 and 873:

Flowering and fruiting. Poplars are

- Page 874 and 875:

nificant number of flowers from the

- Page 876 and 877:

Figure 3—Populus balsamifera, bal

- Page 878 and 879:

Table 5—Populus, poplar, cottonwo

- Page 880 and 881:

Figure 6—Populus, poplar: stages

- Page 882 and 883:

Andrejak GE, Barnes BV. 1969. A see

- Page 884 and 885:

Tauer CG. 1995. Unpublished data. S

- Page 886 and 887:

Figure 2—Prosopis juliflora, mesq

- Page 888 and 889:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 890 and 891:

Table 1—Prunus, cherry, peach, an

- Page 892 and 893:

Table 2—Prunus, cherry, peach, an

- Page 894 and 895:

Table 3—Prunus, cherry, peach, an

- Page 896 and 897:

Tables 5—Prunus, cherry, peach, a

- Page 898 and 899:

Table 6—Prunus, cherry, peach, an

- Page 900 and 901:

Figure 5—Prunus virginianna, comm

- Page 902 and 903:

Crocker W. 1927. Dormancy in hybrid

- Page 904 and 905:

Growth habit, occurrence, and uses.

- Page 906 and 907:

Table 2—Pseudotsuga, Douglas-fir:

- Page 908 and 909:

Table 3—Pseudotsuga, Douglas-fir:

- Page 910 and 911:

mended (table 4), as high heat appl

- Page 912 and 913:

Ching 1959; Dumroese and others 198

- Page 914 and 915:

stored at -7 to 3 °C for 9 months

- Page 916 and 917:

Borno C,Taylor IEP. 1975. The effec

- Page 918 and 919:

Myers JF, Howe GE. 1990. Vegetative

- Page 920 and 921:

Other common names. dalea. Growth h

- Page 922 and 923:

Table 2—Psorothamnus, indigobush:

- Page 924 and 925:

Figure 2— Ptelea trifoliata, comm

- Page 926 and 927:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 928 and 929:

Chudnoff M. 1984. Tropical timbers

- Page 930 and 931:

Kyle and Righetti 1996; Nelson 1983

- Page 932 and 933:

warm water (>10 °C), or holding im

- Page 934 and 935:

McCarty EC, Price R. 1942. Growth a

- Page 936 and 937:

Table 1— Pyrus, pear: nomenclatur

- Page 938 and 939:

Figure 1—Pyrus, pear: fruit and s

- Page 940 and 941:

Seedlings of wild native species ar

- Page 942 and 943:

Figure 1— Quercus, oak: acorns of

- Page 944 and 945:

Table 1—Quercus, oak: nomenclatur

- Page 946 and 947:

Table 2—Quercus, oak: height, see

- Page 948 and 949:

ing does not prevent sowing or prod

- Page 950 and 951:

Figure 3—Quercus macrocarpa, bur

- Page 952 and 953:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 954 and 955:

Figure 2—Rhamnus cathartica, Euro

- Page 956 and 957:

Occurrence. The genus rhododendron

- Page 958 and 959:

Table 1—Rhododendron, rhododendro

- Page 960 and 961:

Figure 1—Rhododendron, rhododendr

- Page 962 and 963:

Table 4—Rhododendron, rhododendro

- Page 964 and 965:

eduction in leaf, stem, and root dr

- Page 966 and 967:

Figure 2—Rhodotypos scandens, jet

- Page 968 and 969:

Table 1—Rhus, sumac; Toxicodendro

- Page 970 and 971:

Figure 1—Rhus, sumac: fruits of R

- Page 972 and 973:

Figure 4—Rhus hirta, staghorn sum

- Page 974 and 975:

Grossulariaceae—Currant family Ri

- Page 976 and 977:

Table 2—Ribes, currant, gooseberr

- Page 978 and 979:

empty seeds, and excess water can t

- Page 980 and 981:

investigators alternated diurnal te

- Page 982 and 983:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 984 and 985:

Figure 1—Robinia, locust: legumes

- Page 986 and 987:

( 1 / 4 in) of soil, as in the nurs

- Page 988 and 989:

example is the multiflora rose, a J

- Page 990 and 991:

the sutures, whether with acid or t

- Page 992 and 993:

The preferred method in official te

- Page 994 and 995:

Arecaceae—Palm family Roystonea O

- Page 996 and 997:

Collection, storage, and germinatio

- Page 998 and 999:

Table 1—Rubus, blackberry, raspbe

- Page 1000 and 1001:

seeds without sexual reproduction)

- Page 1002 and 1003:

flowering and fruit ripening usuall

- Page 1004 and 1005:

Table 5—Rubus, blackberry, raspbe

- Page 1006 and 1007:

Some form of sulfuric acid treatmen

- Page 1008 and 1009:

seeds have germinated and reached a

- Page 1010 and 1011:

Arecaceae—Palm family Sabal Adans

- Page 1012 and 1013:

Table 2—Sabal, palmetto: seed dat

- Page 1014 and 1015:

Table 1—Salix, willow: nomenclatu

- Page 1016 and 1017:

Booth willow, 6 to 9; pussy willow,

- Page 1018 and 1019:

Table 3—Salix, willow: phenology

- Page 1020 and 1021:

Table 4—Salix, willow: cleaned se

- Page 1022 and 1023:

Kim KH, Zsuffa L, Kenny A, Mosseler

- Page 1024 and 1025:

Figure1—Salvia sonomensis, creepi

- Page 1026 and 1027:

ANPS [Arizona Native Plant Society]

- Page 1028 and 1029:

Figure 1—Sambucus nigra spp. ceru

- Page 1030 and 1031:

Table 5—Sambucus, elder: stratifi

- Page 1032 and 1033:

Sapindaceae—Soapberry family Sapi

- Page 1034 and 1035:

Afanasiev M. 1942. Propagation of t

- Page 1036 and 1037:

Figure 2—Sarcobatus vermiculatus,

- Page 1038 and 1039:

Synonyms. Sassafras albidum var. mo

- Page 1040 and 1041:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1042 and 1043:

Anderson E. 2002. Personal communic

- Page 1044 and 1045:

1930; Rehder 1940; Waxman 1957). Wa

- Page 1046 and 1047:

perature, 4 °C, -15 °C, and in wa

- Page 1048 and 1049:

Figure 1—Sequoia sempervirens, re

- Page 1050 and 1051:

Taxodiaceae—Redwood family Sequoi

- Page 1052 and 1053:

Arecaceae—Palm family Serenoa rep

- Page 1054 and 1055:

Figure 1—Serenoa repens, saw-palm

- Page 1056 and 1057:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1058 and 1059:

The seeds are orthodox and should b

- Page 1060 and 1061:

Sapotaceae—Sapodilla family Sider

- Page 1062 and 1063:

Simmondsiaceae—Jojoba family Simm

- Page 1064 and 1065:

(Castellanos and Molina 1990). Dorm

- Page 1066 and 1067:

Figure 1—Solanum dulcamara, bitte

- Page 1068 and 1069:

Growth habit, occurrence and use. T

- Page 1070 and 1071:

Rosaceae—Rose family Sorbaria sor

- Page 1072 and 1073:

Growth habit, occurrence, and uses.

- Page 1074 and 1075:

Figure 2—Sorbus, mountain-ash: tw

- Page 1076 and 1077:

Table 5—Sorbus, mountain-ash: str

- Page 1078 and 1079:

Bignoniaceae—Trumpet-creeper fami

- Page 1080 and 1081:

Growth habit, occurrence, and uses.

- Page 1082 and 1083:

ecomes straw-colored or light brown

- Page 1084 and 1085:

Growth habit, occurrence and use. T

- Page 1086 and 1087:

However, recent research results in

- Page 1088 and 1089:

Growth habit, occurrence and use. T

- Page 1090 and 1091:

Figure 3—Swietenia, mahogany: ger

- Page 1092 and 1093:

used by birds and black bear (Ursus

- Page 1094 and 1095:

22 to 30 °C for 3 to 4 months has

- Page 1096 and 1097:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1098 and 1099:

In common, nodding (S. reflexa C.K.

- Page 1100 and 1101:

Synonym. T. pentrandra Pall. Growth

- Page 1102 and 1103:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1104 and 1105:

at 4 °C for 90 days or until ready

- Page 1106 and 1107:

Pacific yew is common east of the C

- Page 1108 and 1109:

number of cleaned seeds per weight

- Page 1110 and 1111:

efore they are of salable size (Har

- Page 1112 and 1113:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1114 and 1115:

are more difficult to germinate (Tr

- Page 1116 and 1117:

poisonous to sheep, especially smoo

- Page 1118 and 1119:

Malvaceae—Mallow family Thespesia

- Page 1120 and 1121:

Francis JK. 1989. Thespesia grandif

- Page 1122 and 1123:

The 3 Asian species listed (table 1

- Page 1124 and 1125:

Figure 4—Thuja occidentalis, nort

- Page 1126 and 1127:

Tiliaceae—Linden family Tilia L.

- Page 1128 and 1129:

weather conditions) and lack of con

- Page 1130 and 1131:

good germination for all species an

- Page 1132 and 1133:

Synonyms. Toona australis Harms, Ce

- Page 1134 and 1135:

Growth habit, occurrence, and uses.

- Page 1136 and 1137:

then held in open storage until the

- Page 1138 and 1139:

Euphorbiaceae—Spurge family Triad

- Page 1140 and 1141:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1142 and 1143:

can trap more than 100 pollen grain

- Page 1144 and 1145:

Figure 3—Tsuga mertensiana, mount

- Page 1146 and 1147:

Table 6—Tsuga, hemlock: stratific

- Page 1148 and 1149:

or equal to 0.05) (Edwards and El-K

- Page 1150 and 1151:

continue height growth during the s

- Page 1152 and 1153:

Ruth RH. 1974. Tsuga, hemlock. In:

- Page 1154 and 1155:

The mature fruit is a typical, smal

- Page 1156 and 1157:

Growth habit, occurrence, and use.

- Page 1158 and 1159:

Figure 1—Ulmus, elm: samaras of U

- Page 1160 and 1161:

months (Dirr and Heuser 1987). Seed

- Page 1162 and 1163:

Arisumi T, Harrison JM. 1961. The g

- Page 1164 and 1165:

leaves, and seeds have been sold fo

- Page 1166 and 1167:

Seedling development and nursery pr

- Page 1168 and 1169:

Table 1—Vaccinium, blueberry and

- Page 1170 and 1171:

seeds are allowed to dry (Ballingto

- Page 1172 and 1173:

Figure 3—Vaccinium corymbosum, hi

- Page 1174 and 1175:

Germination. No pretreatments are u

- Page 1176 and 1177:

European cranberrybush are eaten by

- Page 1178 and 1179:

Table 3—Viburnum, viburnum: growt

- Page 1180 and 1181:

Table 6—Viburnum, viburnum: lates

- Page 1182 and 1183:

Figure 1—Vitex agnus-castus, lila

- Page 1184 and 1185:

Other common names. northern fox gr

- Page 1186 and 1187:

Arecaceae—Palm family Washingtoni

- Page 1188 and 1189:

Growth habit and occurrence. There

- Page 1190 and 1191:

Table 2—Yucca, yucca: phenology o

- Page 1192 and 1193:

Seedlings should be provided with m

- Page 1194 and 1195:

Figure 2—Zanthoxylum clava-hercul

- Page 1196 and 1197:

Rhamnaceae—Buckthorn family Zizip

- Page 1198 and 1199:

Chenopodiaceae—Goosefoot family Z

- Page 1200 and 1201:

Figure 3—Zuckia brandegei, siltbu

- Page 1202 and 1203:

Gray A. 1876. Grayia brandegei. Pro

- Page 1204 and 1205:

Conversion Factors 1192 Glossary 11

- Page 1206 and 1207:

abortive imperfectly or incompletel

- Page 1208 and 1209:

fruit wall outer layer of fruits in

- Page 1210 and 1211:

polygamo-monoecious species that ar

- Page 1212 and 1213:

A Aceraceae—Maple family Acer L.

- Page 1214 and 1215:

S Salicaceae—Willow family Populu

- Page 1216 and 1217:

C Connor, Kristina F. Bauhinia Park

- Page 1218 and 1219:

Schubert, T. H. Tectona Shaw, Nancy

- Page 1220 and 1221:

auline blanchâtre, Alnus Australia

- Page 1222 and 1223:

Carolina silverbell, Halesia carpen

- Page 1224 and 1225:

Douglas-spruce, Pseudotsuga droopin

- Page 1226 and 1227:

hackmatack, Larix hackmatack, Popul

- Page 1228 and 1229:

Scotch Waterer lacewood, Grevillea

- Page 1230 and 1231:

interior live iron jack Kellogg lau

- Page 1232 and 1233:

western white western yellow Weymou

- Page 1234 and 1235:

silk-oak, Grevillea silktassel, Gar

- Page 1236 and 1237:

Hinds Hinds black Japanese little n

- Page 1238 and 1239:

Figure 1—Cercidium floridum Figur

- Page 1240 and 1241:

Figure 13—Thespesia populnea Figu