Chapter 3 Puberty and Biological Foundations - The McGraw-Hill ...

Chapter 3 Puberty and Biological Foundations - The McGraw-Hill ...

Chapter 3 Puberty and Biological Foundations - The McGraw-Hill ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Deprived <strong>and</strong> Enriched Environments Until the middle of the twentieth<br />

century, scientists believed that the brain’s development was determined almost exclusively<br />

by genetic factors. <strong>The</strong>n, researcher Mark Rosenzweig (1969) conducted a<br />

classic study. He was curious about whether early experiences can change the brain’s<br />

development. He r<strong>and</strong>omly assigned rats <strong>and</strong> other animals to grow up in different environments.<br />

Some lived in an enriched early environment with stimulating features,<br />

such as wheels to rotate, steps to climb, levers to press, <strong>and</strong> toys to manipulate. In contrast,<br />

others lived in st<strong>and</strong>ard cages or in barren, isolated environments. <strong>The</strong> results<br />

were stunning. <strong>The</strong> brains of the animals from “enriched” environments weighed<br />

more <strong>and</strong> had thicker layers, more neural connections, <strong>and</strong> higher levels of neurochemical<br />

activity than the brains of the “deprived” animals. Similar findings occurred<br />

when older animals were reared in vastly different environments, although the results<br />

were not as strong as for younger animals.<br />

Researchers have also found depressed activity in children who grow up in unresponsive<br />

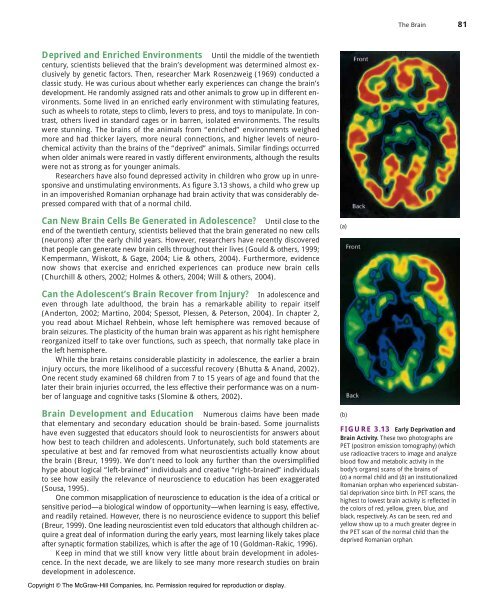

<strong>and</strong> unstimulating environments. As figure 3.13 shows, a child who grew up<br />

in an impoverished Romanian orphanage had brain activity that was considerably depressed<br />

compared with that of a normal child.<br />

Can New Brain Cells Be Generated in Adolescence? Until close to the<br />

end of the twentieth century, scientists believed that the brain generated no new cells<br />

(neurons) after the early child years. However, researchers have recently discovered<br />

that people can generate new brain cells throughout their lives (Gould & others, 1999;<br />

Kempermann, Wiskott, & Gage, 2004; Lie & others, 2004). Furthermore, evidence<br />

now shows that exercise <strong>and</strong> enriched experiences can produce new brain cells<br />

(Churchill & others, 2002; Holmes & others, 2004; Will & others, 2004).<br />

Can the Adolescent’s Brain Recover from Injury? In adolescence <strong>and</strong><br />

even through late adulthood, the brain has a remarkable ability to repair itself<br />

(Anderton, 2002; Martino, 2004; Spessot, Plessen, & Peterson, 2004). In chapter 2,<br />

you read about Michael Rehbein, whose left hemisphere was removed because of<br />

brain seizures. <strong>The</strong> plasticity of the human brain was apparent as his right hemisphere<br />

reorganized itself to take over functions, such as speech, that normally take place in<br />

the left hemisphere.<br />

While the brain retains considerable plasticity in adolescence, the earlier a brain<br />

injury occurs, the more likelihood of a successful recovery (Bhutta & An<strong>and</strong>, 2002).<br />

One recent study examined 68 children from 7 to 15 years of age <strong>and</strong> found that the<br />

later their brain injuries occurred, the less effective their performance was on a number<br />

of language <strong>and</strong> cognitive tasks (Slomine & others, 2002).<br />

Brain Development <strong>and</strong> Education Numerous claims have been made<br />

that elementary <strong>and</strong> secondary education should be brain-based. Some journalists<br />

have even suggested that educators should look to neuroscientists for answers about<br />

how best to teach children <strong>and</strong> adolescents. Unfortunately, such bold statements are<br />

speculative at best <strong>and</strong> far removed from what neuroscientists actually know about<br />

the brain (Breur, 1999). We don’t need to look any further than the oversimplified<br />

hype about logical “left-brained” individuals <strong>and</strong> creative “right-brained” individuals<br />

to see how easily the relevance of neuroscience to education has been exaggerated<br />

(Sousa, 1995).<br />

One common misapplication of neuroscience to education is the idea of a critical or<br />

sensitive period—a biological window of opportunity—when learning is easy, effective,<br />

<strong>and</strong> readily retained. However, there is no neuroscience evidence to support this belief<br />

(Breur, 1999). One leading neuroscientist even told educators that although children acquire<br />

a great deal of information during the early years, most learning likely takes place<br />

after synaptic formation stabilizes, which is after the age of 10 (Goldman-Rakic, 1996).<br />

Keep in mind that we still know very little about brain development in adolescence.<br />

In the next decade, we are likely to see many more research studies on brain<br />

development in adolescence.<br />

Copyright © <strong>The</strong> <strong>McGraw</strong>-<strong>Hill</strong> Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Brain 81<br />

FIGURE 3.13 Early Deprivation <strong>and</strong><br />

Brain Activity. <strong>The</strong>se two photographs are<br />

PET (positron emission tomography) (which<br />

use radioactive tracers to image <strong>and</strong> analyze<br />

blood flow <strong>and</strong> metabolic activity in the<br />

body’s organs) scans of the brains of<br />

(a) a normal child <strong>and</strong> (b) an institutionalized<br />

Romanian orphan who experienced substantial<br />

deprivation since birth. In PET scans, the<br />

highest to lowest brain activity is reflected in<br />

the colors of red, yellow, green, blue, <strong>and</strong><br />

black, respectively. As can be seen, red <strong>and</strong><br />

yellow show up to a much greater degree in<br />

the PET scan of the normal child than the<br />

deprived Romanian orphan.