ZAGREB MOSQUE - Islamska zajednica u Hrvatskoj

ZAGREB MOSQUE - Islamska zajednica u Hrvatskoj

ZAGREB MOSQUE - Islamska zajednica u Hrvatskoj

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

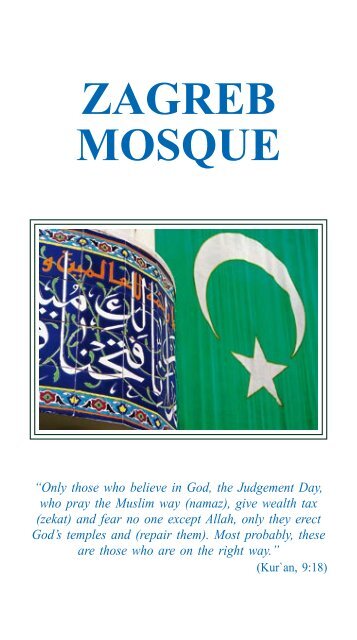

<strong>ZAGREB</strong><br />

<strong>MOSQUE</strong><br />

“Only those who believe in God, the Judgement Day,<br />

who pray the Muslim way (namaz), give wealth tax<br />

(zekat) and fear no one except Allah, only they erect<br />

God’s temples and (repair them). Most probably, these<br />

are those who are on the right way.”<br />

(Kur`an, 9:18)

Series<br />

TOURISM AND HERITAGE<br />

No 73<br />

ISBN 978-953-215-579-2<br />

Editors<br />

Zlatko Hasanbegović, Ana Ivelja-Dalmatin,<br />

Senad Nanić, Mato Njavro,<br />

Maja Perišin, Mirsad Srebreniković,<br />

Iva Vranješ, Marija Vranješ, Khaled Yassin<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Mato Njavro<br />

Responsible Editor<br />

Ana Ivelja-Dalmatin<br />

Photos<br />

Zoran Filipović, Zlatko Hasanbegović, Avdo Imširović,<br />

Patrik Macek, Arhiv Islamskog centra<br />

Publisher<br />

Turistička naklada d.o.o., Zagreb<br />

For Publisher<br />

Marija Vranješ<br />

© Copyright by Turistička naklada<br />

Photolitographs<br />

O_TISAK, Zagreb<br />

Print<br />

PRINTERA, Zagreb<br />

<strong>ZAGREB</strong><br />

<strong>MOSQUE</strong><br />

Koran, sura (chapter) El-Kevser<br />

Text<br />

ZLATKO HASANBEGOVIĆ<br />

SENAD NANIĆ<br />

Translation from English<br />

Živan Filippi, Ph.D.<br />

English Language Revision<br />

Jeremy Irving, B.A.<br />

Zagreb, 2009

The elegant minaret of the Zagreb Mosque<br />

<br />

Sura 1.<br />

THE OPENING SURA – AL-FĀTIH. A<br />

(Proclaimed in Mecca; ajet (line) 7; proclaimed after<br />

the sura One that covers himself – al-Mudettir)<br />

In the name of Allah All-merciful and Pitying<br />

1. Thanks belong to Allah, Who is the Master of worlds,<br />

The City of Zagreb is the<br />

administrative and political<br />

centre of the Republic of Croatia.<br />

Due to its geographical<br />

and geopolitical position, it is<br />

at the crossroads of the routes<br />

between central and southeastern<br />

Europe and the Adriatic<br />

Sea and both its location<br />

and historical development<br />

2. To All-merciful and Pitying,<br />

3. To the Ruler on the Day of Faith;<br />

4. We adore You and ask help from You –<br />

5. Direct us to the right way,<br />

6. To the Way of those whom you lavished with Your blessings,<br />

7. And not of those you are angry with,<br />

Or those who have gone astray!<br />

Koran, sura El-Fatiha<br />

MUSLIMS IN <strong>ZAGREB</strong><br />

A BRIEF HISTORY<br />

have made the city a waypoint<br />

between Catholic central Europe<br />

and Islamic south-eastern<br />

Europe, where Muslim traditions,<br />

culture and heritage are<br />

deeply rooted. This is obvious<br />

to anyone approaching Zagreb<br />

from the East, who will notice<br />

the white minaret of the<br />

Zagreb Mosque on the left.

The grand building of the Zagreb Mosque

Zagreb Mosque was built by great efforts and persistence of the Zagreb<br />

Muslim community<br />

It is one of the landmarks of<br />

the modern quarter of the city,<br />

but also a sign of religious and<br />

cultural identity, and a symbol<br />

of the permanent presence of<br />

the oldest Muslim community<br />

in central Europe. According<br />

to the 2001 census, among<br />

4,437.460 inhabitants of the<br />

Republic of Croatia, there are<br />

56, 777 Muslims of various<br />

ethnic origin (Bosnian, Croat,<br />

Albanians, Romany and others),<br />

comprising 1.28% of<br />

population. After the Roman<br />

Catholics and Orthodox Christians,<br />

Muslims account for the<br />

third largest religious community.<br />

Almost a third of them<br />

live in Zagreb and are at the<br />

centre of Muslim religious,<br />

social, cultural and educational<br />

life in the Republic of Croatia.<br />

According to the same census,<br />

Zagreb has 779, 145 inhabitants,<br />

among whom are 16, 215<br />

Muslims, living throughout the<br />

city. Muslims comprise 2.08%<br />

of the city’s population, and<br />

are the second religious group<br />

after the Roman Catholics.<br />

Although this is a relatively<br />

small Islamic community, Islam<br />

is a traditional and native faith<br />

in the Republic of Croatia and<br />

in the City of Zagreb, practised<br />

The first Zagreb biography of the<br />

God’s envoy Mohamed a.s. from<br />

the 18 th century<br />

for centuries and enjoying a legal<br />

basis. City communal and<br />

fiscal sources record Muslims<br />

in Zagreb in the middle of the<br />

18 th century, when groups of<br />

Muslim merchants from Bosnia<br />

stayed in Zagreb doing<br />

business; they were attracted<br />

by trade privileges and the<br />

revival in trade after the very<br />

long wars between Christian<br />

Austria and the Muslim Ottoman<br />

Empire. The vicinity<br />

of Ottoman Bosnia incited a<br />

greater interest in Islam within<br />

the city’s intellectual and cultural<br />

circles. Thus, the Austrian

Oriental philologist and diplomat<br />

Franz Dombay published<br />

in Zagreb the biography of<br />

God’s emissary Mohammed,<br />

as the pioneering work of European<br />

Oriental Studies. He<br />

described Islamic teaching in<br />

an objective way without the<br />

usual polemical discourse. The<br />

turning-point occurred in 1878<br />

following the Austro-Hungarian<br />

annexation of the westernmost<br />

Ottoman province of<br />

Bosnia and Herzegovina. From<br />

that point, Bosnia and Herzegovina<br />

was within the framework<br />

of the various regions<br />

comprising today’s Republic of<br />

Croatia. The inclusion of Bosnia<br />

and Herzegovina within the<br />

Habsburg Monarchy at the end<br />

of the 19 th century represented<br />

a break with the centuries-old<br />

state, legal and cultural barriers<br />

between Christians and Muslims<br />

in these regions. It was<br />

the beginning of the gradual<br />

formation of a specific Muslim<br />

community in Zagreb, together<br />

with its religious and attendant<br />

social institutions. The first<br />

Muslims in Zagreb after 1878<br />

were young men from Bosnia<br />

and Herzegovina of various<br />

professions who came looking<br />

for job; a special group was<br />

10 10 11 comprised of Muslim pupils<br />

and students at Zagreb University,<br />

who left a significant<br />

mark in Croatian public and<br />

cultural life at the end of the<br />

19 th century. These beginnings<br />

of a Muslim community<br />

are witnessed by the fact that<br />

the first Muslim was buried in<br />

the Zagreb Mirogoj cemetery<br />

in 1883; his tomb marked the<br />

start of the oldest Muslim cemetery<br />

in central Europe. A special<br />

feature of the cemetery is a<br />

two-metre high Islamic monument<br />

from 1873, outstanding<br />

in its beauty and detail.<br />

The census of 1910 recorded<br />

the existence of a small<br />

35-strong Muslim community<br />

in Zagreb which grew to 2000<br />

permanent inhabitants in 1941.<br />

The rise of the Muslim community<br />

in Zagreb created a<br />

need for a legal framework as<br />

a prerequisite for the formation<br />

of a permanent Islamic community,<br />

together with its religious,<br />

cultural and educational<br />

institutions. Therefore in 1916,<br />

the Croatian Sabor (Parliament)<br />

passed “The Act of Recognition<br />

of Islamic confession in<br />

the Kingdoms of Croatia and<br />

Slavonia”, which guaranteed<br />

Islam the same legal protec-<br />

Nišan (stonetomb) of the Ferhatović family in the Mirogoj cemetery<br />

from 1893

12 12 13 tion accorded to other faiths,<br />

and also the possibility of establishing<br />

religious communities<br />

with a close connection<br />

with those in Bosnia and Herzegovina.<br />

This Croatian law of<br />

1916 represents, together with<br />

the Austrian act of 1912, the<br />

oldest recorded recognition<br />

of Islam in Europe outside<br />

an area controlled for centuries<br />

by the Ottoman Empire.<br />

At the beginning of the First<br />

World War, a great many Muslim<br />

soldiers from Bosnia and<br />

Herzegovina were conscripted<br />

in various Austro-Hungarian<br />

military units. Pre-dating legal<br />

recognition of Islam, The Impe-<br />

rial and Royal Islam Military<br />

Spiritual Tutorship in Zagreb<br />

was founded in 1915 for the<br />

spiritual needs of Muslim soldiers<br />

and citizens. This was the<br />

first local Islamic institution at<br />

the head of which presided a<br />

military imam among whose<br />

duties was to register the death<br />

of Muslim soldiers and citizens<br />

until the end of the First<br />

World War, and who taught the<br />

Islamic faith to Muslim youth<br />

in Zagreb schools.<br />

After the establishment of<br />

the new state of the Serbs, Croats<br />

and Slovenes, which was<br />

later called Yugoslavia, a new<br />

wave of Muslim immigrants<br />

A century of the legal recognition of Islam in Croatia The first mesdžid (small mosque) in Zagreb was opened in 1935

1 1 1<br />

same year, as the first Muslim<br />

centre of prayer. Today, it<br />

is the seat of the Mešihat of<br />

the Islamic community in the<br />

Republic of Croatia. The deep<br />

roots of the Muslim community<br />

in Zagreb society were<br />

confirmed in 1940 by the appointment<br />

of the first Muslim<br />

to the city council.<br />

The full administration of<br />

Islamic religious life, as it existed<br />

in Bosnia and Herzegovina,<br />

was implemented at the end<br />

of 1935 when the state sharia<br />

Muslim students from Bosnia<br />

and Herzegovina, who were<br />

also setting up academic clubs<br />

at Zagreb University. Thus,<br />

the sub-committee of Gajret,<br />

a Muslim cultural and educational<br />

society, was founded in<br />

1921 as the first Muslim society<br />

in Zagreb. Later, the Zagreb<br />

local board of the Muslim cultural<br />

society Narodna uzdanica<br />

was established, which later<br />

evolved into an academic society.<br />

This was the central Muslim<br />

cultural and educational in-<br />

The Zagreb Muslim Youth in mekteb (elementary school) in 1930’s court, responsible<br />

for Muslim weddings,<br />

family and<br />

The first Zagreb mufti (1919 -1945) Ismet<br />

ef. Muftić, the founder of the religious end<br />

educational life<br />

from Bosnia and Herzegovina was established, which received<br />

inheritance matters,<br />

arrived in Zagreb to work in not only muftis but also the<br />

was established. It<br />

the important industrial and representatives of the Zagreb<br />

ruled according to<br />

commercial trade centre of Muslim community. The fact<br />

sharia marital and<br />

the new state. This continued that Zagreb radio broadcast<br />

family law, whose<br />

the formation of the Muslim ezan (the Islamic invitation to<br />

application was<br />

community and its religious, prayer) for the first time, and<br />

guaranteed by the<br />

cultural and social institutions then transmitted live important<br />

constitution and<br />

within the Zagreb society. Is- Islamic religious services until<br />

by law. In parallel<br />

lamic religious life began in the 1945, illustrates the growth<br />

with other religious<br />

city in 1919 outside the frame- of the number of Muslims in<br />

institutions, Muswork<br />

of the military spiritual the city. In 1936, the Zagreb<br />

lim societies were<br />

tutorship, when an imam was city authorities provided offi-<br />

established dealing<br />

appointed, who was given the cial premises for the Muslim<br />

with a broad range<br />

title of mufti in 1922. Along community. They were situ-<br />

of cultural, educa-<br />

with the offices of imam and ated in the city centre, at 12<br />

tional and social<br />

mufti, the Islamic religious Tomašićeva Street, where the<br />

matters. They were<br />

commune (Džematski medžlis) mesdžid was opened in the<br />

mostly attended by

1 1 1<br />

The first Zagreb mosque (1944 – 1948), Meštrović’s Pavilion, reconstructed<br />

according to the design of the architects Stjepan Planić and Zvonimir Požgaj

stitution in Zagreb until 1945.<br />

Muslims also gathered around<br />

Društvo zagrebačkih muslimana<br />

(the Society of Zagreb<br />

Muslims), which was active<br />

from 1939 until 1945 and was<br />

also known as the Hrvatsko<br />

muslimansko društvo.<br />

As part of the strengthening<br />

of the Muslim community in the<br />

middle of the 1930’s, there was<br />

an initiative to build a mosque<br />

in Zagreb. This would symbolically<br />

incorporate Islam in traditional<br />

city confessions. The<br />

notion of building a mosque in<br />

Zagreb had surfaced as early<br />

as 1908, as part of the political<br />

and administrative actions<br />

of the Party of Rights during<br />

the annexation of Bosnia and<br />

Herzegovina. This party wanted<br />

to emphasize its pro-Muslim<br />

stance and win over Muslims<br />

for its own aims and was in<br />

tune with the thoughts of the<br />

founder of the modern Croatian<br />

nation, Ante Starčević. The invitation<br />

to tender for the building<br />

of the mosque appeared in<br />

Zagreb newspapers in October<br />

1908. It would meet the needs<br />

of Muslims who regularly<br />

came to the city. Družba braće<br />

hrvatskoga zmaja (The Society<br />

of the Brothers of the Croatian<br />

1 1 1<br />

Dragon) joined the initiative in<br />

1912 and raised donations from<br />

its members to help pay for the<br />

building. However, after some<br />

unsuccessful attempts during<br />

the Yugoslav period after 1918,<br />

the local board of the Muslim<br />

cultural society Narodna uzdanica<br />

concluded in 1936 that<br />

it would establish “a foundation<br />

for the building of a mosque<br />

and other religious and educational<br />

institutions”, together<br />

with Džematski medžlis, the<br />

community of Zagreb, Matica<br />

hrvatska and Hrvatski radiša.<br />

The Zagreb Džematski medžlis<br />

determined the foundation charter<br />

and the statute of the Zaklada<br />

za izgradnju džamije i<br />

zgrada za održavanje džamije<br />

te smještaj islamskih vjerskoprosvjetnih<br />

ustanova u Zagrebu<br />

(The Foundation for building<br />

the mosque and buildings for<br />

the maintenance of the mosque,<br />

and the accommodation of Islamic<br />

religious and educational<br />

institutions in Zagreb). These<br />

documents laid down how<br />

funds would be gathered and<br />

spent for the building of the<br />

mosque and how the foundation<br />

bodies would be organized.<br />

The Zagreb city authorities decided<br />

in October 1940 to build<br />

The interior of the first Zagreb mosque

the mosque at Zelengaj, in the<br />

north of the city, whilst the architect<br />

Zvonimir Požgaj and the<br />

painter Omer Mujadžić were<br />

entrusted with the submission<br />

of the designs. In August 1941,<br />

the city authorities amended the<br />

overall design of the mosque to<br />

include the Artists Home, previously<br />

in the centre of the city,<br />

built to a design of the sculptor<br />

Ivan Meštrović. The mosque<br />

was opened in the summer of<br />

1941. The exterior arrangement<br />

was conceived by one of<br />

the leading Croatian architects<br />

Stjepan Planić, and the interior<br />

20 20 21 of the mosque was designed by<br />

the architect Zvonimir Požgaj.<br />

The three concrete-reinforced<br />

minarets 46 metres high and<br />

the outside fountain (šadrvan)<br />

were completed in the spring of<br />

1943. A new dome was erected<br />

in the interior of the mosque<br />

which brought light into the hall<br />

and carried a one-ton hanging<br />

lamp. The partition walls were<br />

removed, the imam’s office and<br />

two flats, the classroom for religious<br />

studies and two mahfils<br />

(an area restricted to women)<br />

were added, one in the form<br />

of a gallery on the first floor<br />

Part of the fence of the minber (pulpit) in the first Zagreb mosque<br />

Remains of the first Zagreb mosque (ćurs /pulpit, mihrab, minber), the<br />

exhibity in the Islamic Centre<br />

Replica of the interior decoration<br />

in the first Zagreb mosque<br />

and another on the semi-circular<br />

balcony above the entrance<br />

to the hall. The monumental<br />

mihrab, and mimber and ćurs<br />

(pulpits) were situated in the<br />

prayer hall. The walls of the<br />

mosque were lined with green<br />

Italian marble and adorned with<br />

travertine decoration of early<br />

Croatian interlaced-ribbon motifs<br />

and Arabic calligraphy. The<br />

floors were covered with forty<br />

Persian rugs of the Isfahan<br />

type. The opening of The Zagreb<br />

Mosque, which ranked,<br />

through its sheer size and scale,

A motif from the opening of the new Zagreb mosque<br />

22 22 23 Koran the Honourable, the proclaimed God’s word and direction sign<br />

in the life of Muslims<br />

among the world’s outstanding<br />

mosques, represented a symbolic<br />

coronation of the protracted<br />

development of the Muslim<br />

community in Zagreb,<br />

The establishment of communism<br />

after the Second World<br />

War and the deep political and<br />

social changes which ensued<br />

strongly influenced the Zagreb<br />

Muslim community. Following<br />

the social and religious achievements<br />

of the first generation<br />

of Zagreb Muslims, they now<br />

found themselves under various<br />

forms of repression. Muslim<br />

societies and institutions, with<br />

the exception of religious representation,<br />

were dissolved and<br />

banned, whilst the trial and execution<br />

of the Zagreb mufti in<br />

1945, together with the destruction<br />

of minarets and the closure<br />

of the first Zagreb Mosque in<br />

1948, marked the end of the<br />

foundation period of the Muslim<br />

presence in Zagreb. The<br />

Muslim community reverted to<br />

its modest framework of 1918,<br />

and was forced to try to develop<br />

and restore its institutions in<br />

the difficult and unfavourable<br />

circumstances of the post-war<br />

period. The preserved remains<br />

of the first Zagreb Mosque,<br />

among which is the magnificent<br />

mihrab, are exhibited today in<br />

the new mosque’s museum.

Šadrvan (fountain) in the first Zagreb mosque<br />

2 2 2<br />

CONTEMpORARY SITUATION<br />

After the Second World War,<br />

intensive Muslim immigration<br />

to Zagreb from the country’s<br />

regions continued. They<br />

were drawn from various professions,<br />

social strata and ethnic<br />

origins, and among them<br />

were Muslim Albanians from<br />

Kosovo and Macedonia, who<br />

today constitute the main element<br />

of the Muslim community.<br />

An increase in the Muslim<br />

community occurred at<br />

the end of the 1960’s and the<br />

beginning of the 1970’s, when<br />

A view to the façade<br />

The Mosque while building

discussions began about building<br />

a new mosque in Zagreb,<br />

which would become the centre<br />

of Islamic religious and<br />

social life; it would also be a<br />

symbol of the important role<br />

of a great number of Muslims<br />

in Croatian and Zagreb public<br />

and cultural life. Although<br />

the authorities tried through<br />

various administrative means<br />

to make the realization of the<br />

project difficult, the foundation-stone<br />

of the new Zagreb<br />

Mosque was laid in 1981, in<br />

what was then a suburb of<br />

Zagreb, but what is now an<br />

area linked to the city centre<br />

by good roads.<br />

The building of the mosque<br />

was dogged by difficulties<br />

but supported by great dedication<br />

and the persistence of<br />

the community at large and<br />

in particular by its building<br />

committee. It was completed<br />

in 1987 when the mosque was<br />

open to the public as a symbol<br />

of an ancient and reborn community.<br />

The mosque transcended<br />

the local Muslim community<br />

and became one of the most<br />

important Islamic centres in<br />

2 2 2<br />

Europe, due to its programme<br />

of religious, social, cultural<br />

and educational activities. It<br />

connected the more recent<br />

Muslim communities in western<br />

Europe with the original<br />

and traditional Islam in southeastern<br />

Europe.<br />

The restoration and<br />

strengthening of the Zagreb<br />

Muslim community after the<br />

opening of the mosque was<br />

confirmed by the final formation<br />

of independent Islamic<br />

religious institutions in the<br />

Republic of Croatia, with their<br />

seat in Zagreb. The Islamic<br />

community in the Republic<br />

of Croatia is active today as<br />

a recognized and independent<br />

religious community, which<br />

agreed its position and significance<br />

by a contract with the<br />

state on mutual relationships.<br />

The institutions of the Islamic<br />

community in the Republic of<br />

Croatia, which is connected<br />

through reis-ul-ulema in Sarajevo<br />

with the Islamic community<br />

in Bosnia and Herzegovina,<br />

are the Sabor of the<br />

Islamic community, as a national<br />

religious representative<br />

body, the Mešihat with the<br />

Zagreb Ramadan candles

The builders of the Zagreb Mosque<br />

2 2 2

Mosque, a place of inter-religious dialogue<br />

Zagreb mufti as the executive<br />

body of the Sabor, and<br />

the network of Mežlises (Islamic<br />

religious communities)<br />

which are active throughout<br />

the country. The Zagreb<br />

Mosque and the Islamic<br />

Centre took on a significant,<br />

broader social role during and<br />

after the armed aggression<br />

against both the Republic of<br />

Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina<br />

from 1991 to 1995<br />

by becoming a refuge for<br />

thousands of people fleeing<br />

30 30 31 the fighting, and also a centre<br />

of charitable work. The Zagreb<br />

Mosque was a gathering<br />

place for Muslims who took<br />

part in defending the homeland<br />

and in the establishment<br />

of the independent Republic<br />

of Croatia. 39 Zagreb Muslims<br />

gave their lives for Croatia<br />

as part of Croatian Army<br />

units. The monument in the<br />

Islamic Centre is a permanent<br />

reminder of their sacrifice as<br />

well as that of all Muslim<br />

defenders of the Republic of<br />

Croatia from other parts of<br />

the country and also from<br />

Bosnia and Herzegovina.<br />

The Zagreb Mosque and<br />

Islamic Centre is run by the<br />

Executive Committee of the<br />

Medžlis of the Islamic community<br />

of Zagreb, whose members<br />

are chosen by the džemat<br />

- the local Muslim community.<br />

The main task of the Zagreb<br />

Executive Committee of the<br />

Medžlis is to strengthen the<br />

social cohesion of the community,<br />

besides maintaining the<br />

buildings and ensuring that<br />

Visit of the Iranian President Mohammad Khatami<br />

regular religious services and<br />

educational classes can take<br />

place. The Executive Committee<br />

of the Medžlis works<br />

through specialized councils<br />

dealing with particular social<br />

areas, e.g. youth; it also<br />

oversees the work of the Merhamet<br />

charity. 14 imams and<br />

many teachers of Islam undertake<br />

religious instruction,<br />

which takes place regularly<br />

both in the mosque and in the<br />

city’s schools. Wedding ceremonies<br />

are performed in the<br />

mosque and as per the agree-

ment between the state and<br />

the Islamic community, the<br />

Islamic service is recognized<br />

as having full civil and legal<br />

rights. Today, the ‘Dr. Ahmed<br />

Smajlović’ Islamic Grammar<br />

School which is also secondary<br />

modern school, is part of<br />

the mosque and the Islamic<br />

Centre and is integrated into<br />

the Croatian educational system.<br />

It was founded in 1993<br />

as a madrassah - an Islamic<br />

religious school. ‘Arabeske’,<br />

the female choir of the Za-<br />

The Zagreb mufti Ševko ef. Omerbašić<br />

32 32 33 greb Mosque, is well-known<br />

outside Zagreb for its varied<br />

performances and concerts.<br />

The city kindergarten ‘Jasmin’<br />

was opened in the Islamic<br />

Centre for all children,<br />

regardless of their faith, together<br />

with the sports centre<br />

and playground of the football<br />

club Nur. Since opening, both<br />

the Zagreb Mosque and the Islamic<br />

Centre have become a<br />

focus for authentic European<br />

Islamic thinking, confirmed<br />

by its wide literary output, nu-<br />

The Prime Minister of Malaysia Mahathir bin Mohamad visiting the<br />

Islamic Centre<br />

The President of the Republic of Croatia Stjepan Mesić visiting the<br />

Zagreb medrese “Dr. Ahmed Smajlović”

School leavers of the Zagreb medrese “Dr. Ahmed Smajlović”<br />

Sharia wedding in Zagreb<br />

3 3 3<br />

The Mosque – the meeting place of ulema (theologians) from the whole<br />

Islamic world

merous international scientific<br />

symposia.<br />

There is a regular Islamic<br />

meeting on Thursday at the<br />

‘Dr. Sulejman Mašović’ centre,<br />

named after its founder<br />

who was an outstanding Zagreb<br />

Muslim and it is today<br />

one of the oldest institutions<br />

3 3 3<br />

The female choir “Arabeske” have attracted the hearts of the public in<br />

all its performances since 1993<br />

in the city. The Zagreb Islamic<br />

Centre is also well-known in<br />

Europe as a Koran learning<br />

centre, much appreciated in<br />

world Islamic circles, and as a<br />

venue for dialogue with other<br />

faiths.<br />

With its extensive facilities,<br />

the Zagreb Mosque embod-<br />

ies the most significant symbols<br />

of universal meaning of<br />

Islam as a faith for all men<br />

and women, races, locations<br />

and civilizations; and is a permanent<br />

monument to Islamic<br />

values as an inseparable part<br />

of European culture and civilization.<br />

Winners of the table-tennis<br />

tournament in the sports hall of<br />

the Islamic Centre

The “Jasmin” kindergarten<br />

Mekteb (elementary school) in the Islamic Centre<br />

3 3 3<br />

The mayor of Zagreb, a friend of the football club “Nur”<br />

Sports Centre “Nur”

Waiting for the prayer<br />

0 0 1 The Mevlud Feast (the holy day of the birth of Mohamed)<br />

The final celebration of the European competition of learners of the Koran

2 2 3 BUILdING CHARACTERISTICS OF THE<br />

<strong>MOSQUE</strong> ANd ISLAMIC CENTRE<br />

W hen the Zagreb Mosque<br />

is mentioned, one refers<br />

to a large building, the greatest<br />

in this part of Europe. One is<br />

aware of the building’s difficult<br />

inception, the involvement of<br />

prominent individuals and donors,<br />

and one is conscious of<br />

the role of the mosque in the<br />

life of the Zagreb Muslim community.<br />

Sometimes, attention<br />

is drawn to the designers and<br />

builders, but the architectonic<br />

and building characteristics of<br />

the very project are often neglected.<br />

Everybody agrees that<br />

this is a very successful and<br />

aesthetically exceptional enterprise.<br />

The mosque was opened<br />

in 1987 built by the Zagreb<br />

builders “Tehnika”. The man<br />

behind the preliminary design<br />

is Džemal Čelić, an architect<br />

and Professor at Sarajevo<br />

University and a great connoisseur<br />

of the Islamic building<br />

tradition of Bosnia and<br />

Herzegovina. His design was<br />

co-authored by Mirza Gološ,<br />

also an architect from Sarajevo,<br />

whilst the calligraphy is<br />

by Ešref Kovačević, the best<br />

known Bosnian calligrapher of<br />

the time.<br />

Main façade The monumental sliding door of copper, the work of the academic<br />

sculptor Šefkija Baručija

Sedžda (prostration)

An orchard in front of the Mosque<br />

<br />

Džuma (Muslim prayer on Friday)<br />

The first mosque was erected<br />

by God’s emissary Mohamed<br />

a.s. in the village of Kuba<br />

not far from Medina during the<br />

time of the hidžra from Mecca<br />

to Medina. The first mosques<br />

did not yet have all those elements<br />

which constitute recognizable<br />

characteristics of each<br />

Islamic shrine. Thus, with the<br />

first mosques, kibla (the direction<br />

of the prayer towards Mecca)<br />

was marked by one stone<br />

in the wall, whilst the classic<br />

mihrab (the niche in the wall<br />

directed towards Mecca), the<br />

minber (pulpit) and the minaret<br />

became in time the constitutive<br />

elements of every mosque.<br />

ON <strong>MOSQUE</strong>S...<br />

The name ‘mosque’ is derived<br />

from the Arabic root<br />

meaning gathering and being<br />

together; it was used in both<br />

the Ottoman and in the previous<br />

Seljuk tradition for larger<br />

places of worship where common<br />

prayer would be held<br />

on Fridays. The name of the<br />

Tespih (Muslim rosary)

prayer, as well as that of the<br />

day Friday itself – džum, is<br />

derived from the same Arabic<br />

root. The name for the<br />

basic community of Muslims<br />

– džemat also derives from<br />

this root. Another name for<br />

a mosque – mesdžid is older<br />

and is mentioned in the Koran.<br />

Mesdžid means the place of<br />

A view to the interior of the Zagreb Mosque<br />

<br />

sedžda, or the religious expression<br />

of humility before God by<br />

touching the floor with one’s<br />

forehead; this is one element in<br />

each of five daily personal and<br />

obligatory prayers. The word<br />

mosque has not become part of<br />

Arab tradition, but all mosques<br />

and mesdžids are commonly<br />

called mesdžids. From this<br />

came the Spanish<br />

word mezguita,<br />

English mosque and<br />

German Moschee.<br />

It also influenced<br />

the Croatian form<br />

of mošeja, which,<br />

however, was not<br />

adopted due to the<br />

popular traditional<br />

words džamija and<br />

mesdžid. In the Ottoman<br />

tradition in<br />

central and southeastern<br />

Europe, each<br />

place of worship<br />

which has a munara,<br />

or the tower<br />

from which a mullah<br />

calls the faithful<br />

to prayer is džamija<br />

(mosque), and all<br />

other places of worship<br />

are mesdžids.<br />

There are differences<br />

in the interiors of<br />

Hutba (preaching) on Friday<br />

mosques and mesdžids. Both<br />

of them have a mihrab, a niche<br />

in the front wall marking the<br />

obligatory direction for each<br />

common and personal prayer,<br />

which points to Mecca or a<br />

building called Bejtullah, the<br />

first of God’s houses erected<br />

by Ibrahim/Abraham, God’s<br />

emissary. Mosques also have<br />

a minber, a pulpit situated to<br />

the right of the mihrab, from<br />

which the imam addresses the<br />

faithful on Friday and on holy<br />

days, as was done by God’s<br />

emissary Mohammed. To the<br />

left of mihrab, there is ćurs,<br />

from the Arabian name for<br />

chair, from where lectures are<br />

delivered separate from the religious<br />

service. Mosques and<br />

mesdžids can have domes or<br />

roofs, they can have harems<br />

(fenced courtyards), mahfils<br />

(prayer galleries), šadrvans<br />

(fountains) and abdesthans<br />

(basins for ceremonial cleansing<br />

before prayer). There is a<br />

lot of varied mosque typology<br />

throughout history, and in the<br />

many cultures and civilizations<br />

of the Islamic world.

0 0 1 The ceramic calligraphic frieze with the text of the Koran sura “Jasin”<br />

“There is no divinity except God, and Mohamed is God’s envoy”<br />

Besides the basic exterior<br />

and interior architectonic<br />

elements, mosque decor is<br />

the most important feature in<br />

a mosque and renders each<br />

mosque recognizable within<br />

general Islamic architecture.<br />

Images are not forbidden as<br />

can be seen from the rich<br />

tradition of Islamic miniature<br />

painting, which were often<br />

used to illustrate manuscripts<br />

and other artefacts. The prohibition<br />

refers to the use of<br />

ON <strong>MOSQUE</strong> dECOR...<br />

figures for religious purposes.<br />

This is because the Richness of<br />

God’s person is characterized<br />

by the infinite transcendence of<br />

His figure. If it is presented in<br />

only two or three dimensions,<br />

this figure is then completely<br />

unworthy of the Grace directed<br />

towards the heart of man. The<br />

Koran does not speak about<br />

man as an image of God, but<br />

of man’s nature which was<br />

made by God according to his<br />

Nature. The mind is therefore

A detail of the ornamental frieze in the Mosque<br />

directed towards the reality of<br />

the multiplicity of dimension<br />

in abstract thought only, both<br />

in science and in art. The confirmation<br />

of God’s oneness, tehvid,<br />

or the quest for the unity of<br />

God’s principles, does not lead<br />

to a false simplicity of God’s<br />

being. On the contrary, the principle<br />

of tehvid, supported by the<br />

Koran giving God many names,<br />

shaped and described in Deeds,<br />

leads the mind towards fresh<br />

and ever richer forms providing<br />

a harmonious answer to a given<br />

problem, but also permeating<br />

2 2 3 the entirety as well. Therefore<br />

it is natural that Islamic building<br />

heritage is characterized by<br />

a uniformity of construction<br />

and decor, where the three-dimensional<br />

is a natural indeterminate,<br />

continuous and integral<br />

part of the construction, following<br />

the noblest and most<br />

diverse geometrical patterns,<br />

and simultaneously complements<br />

the universal recognition<br />

and essence of Islamic building<br />

art. Islamic decor assumes not<br />

only a pure geometrical pattern,<br />

but also calligraphy and tevrik,<br />

for which the usual expression<br />

in European languages is arabesque.<br />

These are forms based<br />

THE FACILITIES OF THE <strong>ZAGREB</strong><br />

<strong>MOSQUE</strong><br />

Muslims living away from<br />

traditional centres do<br />

not live in a compact neighbourhood,<br />

but are scattered<br />

throughout the town. Therefore<br />

traditional forms of mesdžids<br />

and mosques cannot satisfy all<br />

on geometric rules which continue<br />

harmoniously in an abstract<br />

pattern.<br />

their religious needs. In new<br />

mosques, religious service is<br />

combined with cultural, educational<br />

and social activities.<br />

Such buildings are called Islamic<br />

centres which are similar<br />

to historical models of the

taurant with the divanhan (an<br />

area for meetings and dialogue)<br />

and classrooms for religious<br />

instruction. There are<br />

also flats for imams and guest<br />

rooms on the first floor. The<br />

madrassah is in the basement,<br />

which also has a kindergarten<br />

and a youth club with a small<br />

amphitheatre. In accordance<br />

with the design of the architect,<br />

Džemal Čelić, the building<br />

is divided according to its<br />

function. The southern section<br />

forms the area of the mosque<br />

and the northern section the<br />

The library of the Islamic Centre<br />

The restaurant in the Islamic<br />

Centre, a place of the traditional<br />

culinary art Congress Hall “Hadži Salim Šabić”<br />

largest mosque complexes in<br />

big traditional Islamic centres,<br />

capable of hosting other<br />

cultural and educational activities.<br />

As an Islamic Centre,<br />

the Zagreb Mosque fulfils<br />

mesdžid and a praying area<br />

and other functions too. The<br />

whole complex encompasses<br />

around 10,000 square metres,<br />

and consists of three sections:<br />

prayer, social and residential<br />

(an apartment for the<br />

imams and accommodation<br />

for guests). On the groundfloor,<br />

there is a congress hall,<br />

a reading room, offices, a res-<br />

Traditional cuisine

They are defined by an equilateral<br />

triangle, where every side<br />

is equal to the diameter of the<br />

parabola’s axial rotation. The<br />

rotational axes are not vertical<br />

but have a deviation which<br />

forms the symmetry of a threesided<br />

pyramid. This grouping is<br />

similar to a cluster of three soap<br />

bubbles affected by a force opposing<br />

their gravitation. Additionally,<br />

the construction of the<br />

dome is emphasized by vertical<br />

apertures enabling strong<br />

penetration of natural light to<br />

the very top of the dome. The<br />

dome is supported by three<br />

vertical parabolic consoles,<br />

transforming the dome into a<br />

strong visual identity for the<br />

entire community. At the same<br />

time, this enables the spread<br />

of natural light into gently<br />

curved white planes inside the<br />

dome and obviates the need for<br />

windows and selective natural<br />

lightning. The minaret has an<br />

original design: the traditional<br />

elegant cylinder of Ottoman<br />

Interesting construction of the Zagreb Mosque – a connection of the<br />

traditional and modern<br />

accompanying facilities. They<br />

are connected by a shallow<br />

tract emphasized by the small<br />

dome of the reading room and<br />

a spacious access terrace. The<br />

area of the mosque has been<br />

turned by approximately 45º<br />

in the direction of Mecca.<br />

The size of the Mosque is<br />

emphasized by its construction.<br />

The most important element is<br />

the dome, where the traditional<br />

Ottoman monumental circular<br />

dome has been constructed<br />

in a reinforced-concrete parabola.<br />

There are three cuts of<br />

rotational parabolas, elements<br />

created by their axial rotation.<br />

minarets is gently slanted into<br />

the form of an elongated cone<br />

42 metres high, rendering the<br />

dome even more dynamic. The<br />

external entrance to the mosque<br />

is accented with a small parabolic<br />

dome projecting from the<br />

main façade and lined with<br />

white marble. Three huge glid-

Dome – a strong visual identity of džemat (community of the faithful)<br />

The contact of modern architecture and the traditional Islamic building<br />

heritage<br />

ing bronze doors, designed by<br />

the academic sculptor Šefkija<br />

Baručija, are inserted into the<br />

dome. The northern section of<br />

facilities was not given prominence<br />

and is subordinate to the<br />

majesty of the mosque. The<br />

main façade is adorned with<br />

engraved calligraphy Bismillah,<br />

which is found at the beginning<br />

of each chapter of the Koran.<br />

The translation reads: “In the<br />

name of God, the All-merciful”.<br />

The mosque is at once a<br />

building of the Islamic tradition<br />

and a unique building of modern<br />

expression. By using construction<br />

techniques to achieve<br />

the basic element of form, the<br />

Zagreb Mosque naturally continues<br />

the tradition of modern<br />

Zagreb architecture. It also<br />

evokes the heritage of Islam<br />

where innovative architects<br />

have produced many masterpieces.<br />

Play of lights

0 0 1 “… Direct your face towards the inviolable mesdžid (place of<br />

prostration)…” (Koran 2:144)<br />

INTERIOR OF THE <strong>MOSQUE</strong><br />

The interior elements follow<br />

the traditional function of<br />

modern interior design. Thus<br />

mihrab, which is traditionally<br />

formed as a niche in the wall,<br />

is shaped in the<br />

Zagreb mosque as<br />

a parabolic element<br />

emerging from the<br />

wall in which it is<br />

then inserted. The<br />

mihrab is adorned<br />

by calligraphy on<br />

the edge of the<br />

opening of the<br />

niche with the Ajetu-l-kursija<br />

text, the<br />

Koran text (2:255)<br />

referring to God’s<br />

permanent creation<br />

and celebrating<br />

Him by all on earth<br />

and in the heavens.<br />

The calligraphy is written in<br />

the neshi style of Arabic script,<br />

one which is geometrically<br />

standardized for the purpose<br />

of reproducing Koranic text.<br />

Mihrab – a sign-post towards Mecca Levha (sentence from the Koran) with the<br />

name of Allah

Minber, the place of imam’s preaching<br />

2 2 3

Valuable carpets and a calligraphic ceramic frieze, a gift of the<br />

Iranian people to the Zagreb Mosque<br />

The Koran imperative to the<br />

believer to direct his face towards<br />

the inviolable mesdžid<br />

in Mecca is inscribed in the<br />

niche of the mihrab . Two<br />

medallions with Allah’s name<br />

are at the top of the mihrab,<br />

on both sides. The designer of<br />

the Zagreb Mosque accentu-<br />

<br />

ates his monotheism, but also<br />

Islamic ecumenism, by not<br />

including several medallions<br />

with the name of God and<br />

the names of God’s emissary,<br />

Mohammed, and the first four<br />

just halifs – the chosen rulers<br />

of the first historical Islamic<br />

state. Other architectonic ele-<br />

ments of the interior, such as<br />

the minber and mahfil, follow<br />

the distorted plane resulting<br />

from lowering dome segments<br />

to the floor behind the mihrab<br />

and columns supported by the<br />

mahfil. The front part of the<br />

supporting beam of the mahfil<br />

is decorated with a ceramic<br />

calligraphic frieze made in<br />

Iran with the text of a Koran’s<br />

sura – the chapter Jasin,<br />

speaking about mission and<br />

faith on the Judgment Day.<br />

The interior of the mosque is<br />

adorned with valuable carpets,<br />

the gift of the Iranian people<br />

to the Zagreb Muslims.

Circular staircases connect mahfil (gallery) with the main preaching hall<br />

Mahfil (a preaching area for women)<br />

Ćurs, a small preaching room

Sunset

5<br />

17<br />

6<br />

11<br />

2<br />

ČRNOMEREC<br />

PREČKO<br />

Sveti Duh<br />

ZAPADNI<br />

KOLODVOR<br />

12 93<br />

Mandaličina<br />

Selska<br />

LJUBLJANICA<br />

Slovenska<br />

RELJKOVIĆEVA<br />

Talovčeva<br />

Hanuševa<br />

1<br />

Jagićeva<br />

Nehajska<br />

Austrijska<br />

0 0 1 MIHALJEVAC<br />

MANDALIČINA<br />

Gračanske stube<br />

Jandrićeva<br />

Adžijina Vodnikova<br />

Trešnjevački trg<br />

Badalićeva<br />

Tehnički<br />

m.<br />

Zagrepčanka<br />

Jadranska avenija<br />

JANDRIĆEVA<br />

15<br />

15<br />

8<br />

14<br />

BRITANSKI TRG<br />

Britanski trg<br />

Frankopan.<br />

Trg m. Tita<br />

Slavenskoga<br />

M. Radev<br />

Petrovaradinska<br />

Rudeška<br />

Jarun<br />

Staglišće<br />

Srednjaci<br />

Horvati<br />

Knežija<br />

Stud.dom<br />

"S.Radić”<br />

USPINJAČA<br />

Frankopanska<br />

6<br />

11<br />

1<br />

17<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

12 13 17 14 4 9<br />

5 1714 4<br />

Grač. Mihaljevac<br />

Gračani<br />

Radićevo šetalište<br />

Gupčeva zvijezda<br />

Zrinjevac<br />

Stud. centar<br />

Vrbik<br />

Belostenčeva<br />

Grškovićeva<br />

Klinika<br />

za<br />

traumat.<br />

Sveučilišna<br />

aleja<br />

Učiteljski fakultet<br />

Vjesnik<br />

Prisavlje<br />

Veslačka<br />

Savski gaj<br />

KAPTOL<br />

TRG BANA<br />

J.JELAČIĆA<br />

TRG<br />

MAŽURANIĆA<br />

Botan.<br />

vrt<br />

Vodnikova<br />

4 SAVSKI MOST<br />

7<br />

Trnsko<br />

DOLJE<br />

GLAVNI<br />

KOLODVOR<br />

13<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

9<br />

Velesajam<br />

11 1214 8 4<br />

Miramarska<br />

Siget<br />

7<br />

14<br />

Draškovićeva<br />

Branimirova<br />

Lisinski<br />

6<br />

SOPOT<br />

Trg hrv.<br />

velikana<br />

Sheraton<br />

Branimir.<br />

Kruge<br />

Središće<br />

Vončinina<br />

Trg žrtava<br />

fašizma<br />

6<br />

8<br />

2<br />

Branimir.<br />

trž.<br />

Strojarska<br />

Utrina<br />

KVATERNIKOV<br />

TRG<br />

Petrova<br />

1<br />

17<br />

9<br />

13<br />

8<br />

13<br />

7 5<br />

2 8 6 7 5<br />

HEINZELOVA<br />

Šubićeva<br />

Mašićeva<br />

Jordanovac<br />

Bukovačka<br />

Hondlova<br />

Svetice<br />

Ravnice<br />

Tuškanova<br />

Heinzelova<br />

Šulekova<br />

Harambašićeva<br />

Trg kralja Petra Krešimira IV<br />

AUTOBUSNI KOLODVOR<br />

Držićeva<br />

Olipska<br />

Slavonska<br />

Folnegovićevo<br />

naselje<br />

Most mladosti<br />

14<br />

ZAPRUĐE<br />

¸5<br />

MAKSIMIR<br />

Radnička<br />

Heinzelova<br />

Donje Svetice<br />

Ivanićgradska<br />

1<br />

17<br />

9<br />

BORONGAJ<br />

Ferenščica<br />

5<br />

13<br />

3 13<br />

3<br />

2<br />

8 6 7<br />

Tržnica<br />

Kvatrić<br />

Getaldićeva<br />

Čavićeva<br />

Ljubijska<br />

12<br />

7<br />

DUBRAVA<br />

SVETICE<br />

13<br />

ŽITNJAK<br />

Elka<br />

Munja<br />

Zagrebački<br />

transporti<br />

2<br />

3 SAVIŠĆE<br />

L E G E N D A<br />

L E G E N D<br />

Kapucinska<br />

Grižanska<br />

Dankovečka<br />

Čulinečka<br />

Aleja javora<br />

TRAM st. u oba smjera<br />

TRAM stop - both directions<br />

TRAM st. u jednom smjeru<br />

TRAM stop - one direction<br />

Besplatan prijevoz<br />

Free rides<br />

Autobusni terminali<br />

BUS terminal<br />

Poljanice IV<br />

11<br />

DUBEC<br />

4

2 2 TOURIST INFORMATION<br />

Islamic Centre Zagreb<br />

Medžlis of the Islamic community<br />

Gavellina 40<br />

tel. 385 1 61 37 162<br />

Đulbehar (rose flower) in Zagreb<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

www.islamska-<strong>zajednica</strong>.hr<br />

e-mail: info@islamska-<strong>zajednica</strong>.hr<br />

Muslims in Zagreb – A Brief History . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

Contemporary Situation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25<br />

Building Characteristics of the Mosque and Islamic Centre . . . . . . . . . 43<br />

On Mosques... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47<br />

On Mosque Decor... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51<br />

The Facilities of the Zagreb Mosque . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53<br />

Interior of the Mosque . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61