Culture Wars in the Age of Enlightenment - Bowdoin College

Culture Wars in the Age of Enlightenment - Bowdoin College

Culture Wars in the Age of Enlightenment - Bowdoin College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

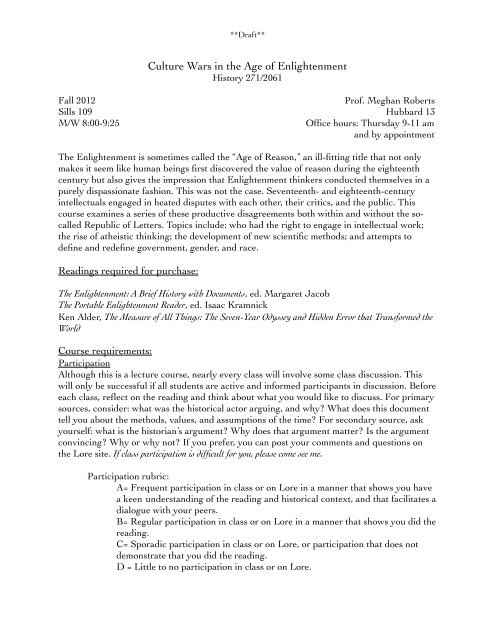

<strong>Culture</strong> <strong>Wars</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong><br />

History 271/2061<br />

Fall 2012 Pr<strong>of</strong>. Meghan Roberts<br />

Sills 109 Hubbard 13<br />

M/W 8:00-9:25 Office hours: Thursday 9-11 am<br />

and by appo<strong>in</strong>tment<br />

The <strong>Enlightenment</strong> is sometimes called <strong>the</strong> “<strong>Age</strong> <strong>of</strong> Reason,” an ill-fitt<strong>in</strong>g title that not only<br />

makes it seem like human be<strong>in</strong>gs first discovered <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> reason dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> eighteenth<br />

century but also gives <strong>the</strong> impression that <strong>Enlightenment</strong> th<strong>in</strong>kers conducted <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>in</strong> a<br />

purely dispassionate fashion. This was not <strong>the</strong> case. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century<br />

<strong>in</strong>tellectuals engaged <strong>in</strong> heated disputes with each o<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>ir critics, and <strong>the</strong> public. This<br />

course exam<strong>in</strong>es a series <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se productive disagreements both with<strong>in</strong> and without <strong>the</strong> socalled<br />

Republic <strong>of</strong> Letters. Topics <strong>in</strong>clude: who had <strong>the</strong> right to engage <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectual work;<br />

<strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> a<strong>the</strong>istic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> new scientific methods; and attempts to<br />

def<strong>in</strong>e and redef<strong>in</strong>e government, gender, and race.<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>gs required for purchase:<br />

**Draft**<br />

The <strong>Enlightenment</strong>: A Brief History with Documents, ed. Margaret Jacob<br />

The Portable <strong>Enlightenment</strong> Reader, ed. Isaac Kramnick<br />

Ken Alder, The Measure <strong>of</strong> All Th<strong>in</strong>gs: The Seven-Year Odyssey and Hidden Error that Transformed <strong>the</strong><br />

World<br />

Course requirements:<br />

Participation<br />

Although this is a lecture course, nearly every class will <strong>in</strong>volve some class discussion. This<br />

will only be successful if all students are active and <strong>in</strong>formed participants <strong>in</strong> discussion. Before<br />

each class, reflect on <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g and th<strong>in</strong>k about what you would like to discuss. For primary<br />

sources, consider: what was <strong>the</strong> historical actor argu<strong>in</strong>g, and why? What does this document<br />

tell you about <strong>the</strong> methods, values, and assumptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time? For secondary source, ask<br />

yourself: what is <strong>the</strong> historian’s argument? Why does that argument matter? Is <strong>the</strong> argument<br />

conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g? Why or why not? If you prefer, you can post your comments and questions on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Lore site. If class participation is difficult for you, please come see me.<br />

Participation rubric:<br />

A= Frequent participation <strong>in</strong> class or on Lore <strong>in</strong> a manner that shows you have<br />

a keen understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g and historical context, and that facilitates a<br />

dialogue with your peers.<br />

B= Regular participation <strong>in</strong> class or on Lore <strong>in</strong> a manner that shows you did <strong>the</strong><br />

read<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

C= Sporadic participation <strong>in</strong> class or on Lore, or participation that does not<br />

demonstrate that you did <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

D = Little to no participation <strong>in</strong> class or on Lore.

**Draft**<br />

Assignments<br />

Summaries: I will <strong>of</strong>ten ask you to write a 150-word summary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day’s read<strong>in</strong>g. These<br />

should be given to me <strong>in</strong> class, with <strong>the</strong> word count noted at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text. These<br />

summaries are not analytical but are <strong>in</strong>stead a quick articulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t or<br />

argument <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g. The po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> this exercise is tw<strong>of</strong>old: first, to teach you to process<br />

large quantities <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation and to identify <strong>the</strong> most important components <strong>of</strong> that body <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge and, second, to help you learn to write <strong>in</strong> clear and concise prose without excess<br />

language. These are graded with a √+, √, or √-<br />

Papers: You will write two papers for this class. The first is a five page biographical sketch <strong>of</strong> a<br />

historical actor. The goal <strong>of</strong> this assignment is to use <strong>the</strong> genre <strong>of</strong> biography to better<br />

understand broad <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>in</strong> history: how is this person a product <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir time? You will also<br />

present your f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to <strong>the</strong> class; see below. The paper will be due on <strong>the</strong> day you give your<br />

oral presentation.<br />

The second paper is a six to eight page paper. You will choose a controversial and/or<br />

popular issue and will explore <strong>the</strong> historical context <strong>of</strong> that issue. Consider: Why did your<br />

subject attract so much attention? Was it controversial? Why or why not? What does this tell<br />

you about eighteenth-century history? How do <strong>the</strong>se debates cont<strong>in</strong>ue to resonate today? The<br />

topic is <strong>of</strong> your choos<strong>in</strong>g, although I urge caution about tak<strong>in</strong>g on more than you can handle<br />

<strong>in</strong> a paper <strong>of</strong> this length. A narrow focus — e.g., wigs, cosmetics, c<strong>of</strong>fee, lightn<strong>in</strong>g rods, female<br />

skeletons — is generally most successful. I encourage you to meet with me to discuss your<br />

paper topic well <strong>in</strong> advance. The Kramnick reader would be a good place to scavenge for<br />

sources, as would <strong>the</strong> Internet History Sourcebook available at http://www.fordham.edu/<br />

halsall/mod/modsbook.asp<br />

Each student has three extension days to apply to <strong>the</strong>se papers at <strong>the</strong>ir discretion. If<br />

you want to use an extension day, please simply turn <strong>in</strong> a hard copy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> assignment as well<br />

as an email attachment. Note <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> extension days you used on <strong>the</strong> cover page.<br />

I focus on <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g categories when grad<strong>in</strong>g written work: your argument, <strong>the</strong><br />

evidence you use to support it, <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> your paper, and <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> your prose. See<br />

<strong>the</strong> rubric for more details.<br />

All papers should be <strong>in</strong> 12-po<strong>in</strong>t font and double-spaced. Please <strong>in</strong>clude a cover letter<br />

that answers <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g questions <strong>in</strong> one or two sentences each: 1) What is <strong>the</strong> argument <strong>of</strong><br />

your paper? 2) What do you like best about <strong>the</strong> paper? 3) What worries you <strong>the</strong> most about<br />

your paper?<br />

Paper rubric:<br />

A. As def<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>College</strong>, an A student “has mastered <strong>the</strong> material <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> course<br />

and has demonstrated exceptional critical skills and orig<strong>in</strong>ality.” An A paper is thus an<br />

outstand<strong>in</strong>g piece <strong>of</strong> historical analysis. The paper has a persuasive argument that<br />

demonstrates <strong>the</strong> author’s own take on a historical problem and is well-founded <strong>in</strong> primary<br />

and secondary sources. The argument is <strong>in</strong>troduced early <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> paper and is developed <strong>in</strong><br />

successive paragraphs. The prose is sophisticated, clear, and fluid. The structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> paper<br />

showcases <strong>the</strong> student’s argument. The paper exceeds my expectations for what a student<br />

might accomplish with a given assignment.

B. Bowdo<strong>in</strong> stipulates that a B student is one who “has demonstrated a thorough and<br />

above average understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> material <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> course.” A B paper is a good piece <strong>of</strong><br />

historical analysis. The paper has a solid argument, but it might be less orig<strong>in</strong>al or have a<br />

shakier evidentiary foundation than those <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> A category. The prose is clear and free <strong>of</strong><br />

major grammatical problems. The paper is well-organized and proceeds <strong>in</strong> logical fashion. It<br />

somewhat exceeds and/or meets my expectations for what a student could accomplish with a<br />

given assignment.<br />

C. The <strong>College</strong> considers a C student to be one who “has demonstrated a thorough and<br />

satisfactory understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> material <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> course.” A C paper is an average piece <strong>of</strong><br />

historical analysis that might have one or more <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g problems. The paper might<br />

have an argument, but it is not grounded <strong>in</strong> primary and/or secondary sources. The prose<br />

might also be clunky, grammatically <strong>in</strong>correct, or hard to follow. The organization might<br />

h<strong>in</strong>der <strong>the</strong> clarity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argument. The paper meets or falls somewhat short <strong>of</strong> my<br />

expectations.<br />

D. Bowdo<strong>in</strong> def<strong>in</strong>es a D student as one who “has demonstrated a marg<strong>in</strong>ally<br />

satisfactory understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> basic material <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> course.” A D paper is a completed<br />

assignment that shows some understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> course material, but has significant<br />

problems with argument, evidence, and prose.<br />

Oral presentation: You will tell <strong>the</strong> class about <strong>the</strong> historical figure who comprised <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong><br />

your first paper. Your presentation should provide enough background on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual so<br />

that your classmates know who/what you’re talk<strong>in</strong>g about, but you don’t want to get lost <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> details. The most important part <strong>of</strong> your presentation is <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> your figure:<br />

what <strong>the</strong>ir life tells historians about <strong>the</strong> time <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>y lived. Your presentation should<br />

have an argument, and it should be <strong>the</strong> same argument featured <strong>in</strong> your paper. You will be<br />

graded on <strong>the</strong> clarity <strong>of</strong> your presentation and how engag<strong>in</strong>gly you present your material. The<br />

presentation should be five to ten m<strong>in</strong>utes long. Costumes, props, and slides are encouraged<br />

but are not required.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al exam: There will be an open-note, take-home f<strong>in</strong>al exam which will be due on December<br />

14 at 12:00 (noon). I will only change <strong>the</strong> due date for <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al if you have three exams with<strong>in</strong><br />

a two day period or if I receive notification from your dean.<br />

The exam will have three parts: identifications, quotations, and an essay. In <strong>the</strong><br />

identification section, I want you to only spend one or two sentences identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> person,<br />

term, or event. The bulk <strong>of</strong> your response should consider significance: how you can connect<br />

that particular term to a host <strong>of</strong> historical issues and <strong>the</strong>mes. The quotations will showcase<br />

your skills at analyz<strong>in</strong>g primary sources, and <strong>the</strong> essay will <strong>in</strong>volve mak<strong>in</strong>g a concise and clear<br />

historical argument. Although <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al is at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> class, I encourage you to th<strong>in</strong>k<br />

about it throughout so that your notes will be useful to you.<br />

Grad<strong>in</strong>g scale:<br />

92-100: A<br />

90-91: A-<br />

88-89: B+<br />

82-87: B<br />

80-81: B-<br />

**Draft**<br />

78-79: C+<br />

72-77: C<br />

70-71: C-<br />

60-70: D<br />

59 and below: F

Grade distribution:<br />

Participation: 20%<br />

Summaries: 10%<br />

Paper #1: 15%<br />

Paper #2 : 25%<br />

Oral presentation: 10%<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al exam: 20%<br />

Athletics: Please let me know if and when you will miss class, as well as how you plan to make<br />

up missed work.<br />

Academic Integrity: All students must adhere to <strong>the</strong> Academic Honor and Social Code (http://<br />

www.bowdo<strong>in</strong>.edu/studentaffairs/student-handbook/college-policies/<strong>in</strong>dex.shtml) Failure to<br />

do so may result <strong>in</strong> referral to <strong>the</strong> Judicial Board.<br />

NB: You must complete all assignments <strong>in</strong> order to receive credit for this course.<br />

Class Meet<strong>in</strong>gs and Assignments<br />

September 3: What is <strong>the</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong>, and why does it matter?<br />

September 5: Community, civility, and conflict <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Republic <strong>of</strong> Letters<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Steven Shap<strong>in</strong>, “The House <strong>of</strong> Experiment <strong>in</strong> Seventeenth-Century<br />

England,” Isis 79, pp. 373-404, available via JSTOR; César Dumarsais,<br />

“Def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> a Philosophe,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 21-23.<br />

Questions: How would you describe <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> science and philosophy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

seventeenth century? How were <strong>the</strong>y alike, and how were <strong>the</strong>y different? How<br />

did philosophes def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>ir fellow citizens <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Republic <strong>of</strong> Letters?<br />

Part I: Reform<strong>in</strong>g Religion and Morality<br />

September 10: Religion and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong><br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Treatise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Three Impostors <strong>in</strong> Jacob, pp. 94-114; John Locke, A Letter<br />

Concern<strong>in</strong>g Toleration <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 81-90; Isaac Newton, “The Argument for<br />

a Deity,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 96-100; Baron d’Holbach, “No Need <strong>of</strong><br />

Theology...Only <strong>of</strong> Reason,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 140-150.<br />

Questions: How would you characterize <strong>the</strong> various religious positions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

authors? What sort <strong>of</strong> argument are <strong>the</strong>y mak<strong>in</strong>g? How do <strong>the</strong>y def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between religion and reason? Who is <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>tended audience?<br />

September 12: The limits <strong>of</strong> toleration? Jews and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong><br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Moses Mendelssohn, Jerusalem: Or on Religious Power and Judaism, <strong>in</strong> Jacob,<br />

pp. 208-219; Gotthold Ephraim Less<strong>in</strong>g, Nathan <strong>the</strong> Wise, pp. 23-75, available<br />

via e-reserve.<br />

Questions: How do Mendelssohn and Less<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> ideal relationship between<br />

religion, reason, and <strong>the</strong> state? How do <strong>the</strong>y build upon <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>the</strong><br />

last class, and how do <strong>the</strong>y differ from <strong>the</strong>m?<br />

September 17: Love, marriage, and celibacy<br />

**Draft**

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Julie, or <strong>the</strong> New Héloïse, pp. 25-49, 118-146, 279-301,<br />

available via e-reserve<br />

Questions: What do you th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> characters, especially Julie and St. Preux? What<br />

is <strong>the</strong> moral message <strong>of</strong> this novel? Why did this novel acquire a huge and<br />

devoted readership?<br />

September 19: Torture and capital punishment<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Cesare Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp.<br />

525-532; Jeremy Bentham, “Cases unmeet for punishment….”, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick,<br />

pp. 541-546; Lynn Hunt, Invent<strong>in</strong>g Human Rights, pp. 70-112, available via<br />

e-reserve. Summary <strong>of</strong> Hunt due.<br />

Questions: Why did many learned <strong>in</strong>dividuals come to oppose torture and<br />

punishment? What did <strong>the</strong>y propose as new methods <strong>of</strong> social control?<br />

Part II: Unlock<strong>in</strong>g Nature’s Secrets<br />

September 24: Natural history<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Jay Smith, Monsters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gévaudan, pp. 1-6, 27-59, available via e-reserve;<br />

Comte de Buffon, “The Rat,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 60-63.<br />

Questions: What topics and questions seemed to fasc<strong>in</strong>ate eighteenth-century<br />

naturalists and readers, and why? How would you describe Buffon’s methods<br />

and his style <strong>of</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

September 26: What is life?<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Julien Offray de la Mettrie, Man a Mach<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 202-209 ;<br />

Jessica Risk<strong>in</strong>, “The Defecat<strong>in</strong>g Duck: Or, <strong>the</strong> Ambiguous Orig<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Artificial<br />

Life, Critical Inquiry (Summer 2003) Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 599-633, available via<br />

JSTOR.<br />

Questions: Are Mettrie’s text and Risk<strong>in</strong>’s duck just strange outliers, or do <strong>the</strong>y tell<br />

you someth<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>of</strong>ound about <strong>the</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong>? What are <strong>the</strong> moral and<br />

philosophical implications <strong>of</strong> humans be<strong>in</strong>g mach<strong>in</strong>es, or mach<strong>in</strong>es seem<strong>in</strong>g<br />

alive?<br />

October 1: Sex, race, and gender<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Londa Schieb<strong>in</strong>ger, The M<strong>in</strong>d Has No Sex?, pp. 160-213, available via<br />

‘ e-reserve; Mary Wollstonecraft, V<strong>in</strong>dication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong> Woman, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick,<br />

pp. 618-628; Denis Diderot, Supplement to Bouga<strong>in</strong>eville’s Voyage, <strong>in</strong> Jacob, pp.<br />

160-176. Summary <strong>of</strong> Schieb<strong>in</strong>ger due.<br />

Questions: How did eighteenth-century savants reth<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> race and sex?<br />

How did <strong>the</strong>y make <strong>the</strong>ir arguments, and why is this significant?<br />

October 3: midterm<br />

October 8: Fall break<br />

**Draft**<br />

October 10: The Oxygen Combat and Mesmerism

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Marquis de Condorcet, “Utility <strong>of</strong> Science,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 64-69; Joseph<br />

Priestley, “Organization <strong>of</strong> Scientific Research,” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 69-73;<br />

Jessica Risk<strong>in</strong>, Science <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Age</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sensibility, pp. 189-225, available via<br />

e-reserve.<br />

Questions: How do natural philosophers dist<strong>in</strong>guish real science from fake science at<br />

<strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eighteenth century? What does a real scientist look like? How<br />

has this changed from <strong>the</strong> seventeenth century (i.e., <strong>the</strong> Shap<strong>in</strong> article we read<br />

at <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> class)?<br />

Part III: Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Society<br />

**Draft**<br />

October 15: Happ<strong>in</strong>ess, optimism, and progress<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Denis Diderot, Rameau’s Nephew, selected pages OR Voltaire, Candide,<br />

selected pages. I will split <strong>the</strong> class <strong>in</strong> half, with one half read<strong>in</strong>g Voltaire and<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r Diderot.<br />

Questions: How would you describe Diderot and Voltaire’s take on optimism and<br />

progress? Were <strong>the</strong>se texts what you expected <strong>of</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong> philosophers?<br />

Why or why not?<br />

October 17: Education, or how to form <strong>the</strong> ideal citizen<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 229-235 and pp. 568-579;<br />

Julia Douthwaite, The Wild Girl, Natural Man, and <strong>the</strong> Monster, pp. 134-160,<br />

available via e-reserve. Summary <strong>of</strong> Douthwaite due.<br />

Questions: Why was education so important to eighteenth-century th<strong>in</strong>kers? What<br />

does <strong>the</strong> Douthwaite text tell you about <strong>the</strong> social impact <strong>of</strong> pedagogical<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory?<br />

October 22: Freemasons<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Margaret Jacob, Liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Enlightenment</strong>, pp. 52-95, available via e-reserve;<br />

images on pp. 23, 36 <strong>in</strong> Jacob.<br />

Questions: Why did so many <strong>in</strong>dividuals choose to ga<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> lodges and participate <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se ceremonies? Why could this be upsett<strong>in</strong>g to many secular and religious<br />

leaders?<br />

October 24: In-class view<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Mozart’s The Magic Flute<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: None!<br />

October 29: Inoculation<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Harry Marks, “When <strong>the</strong> State Counts Lives,” pp. 51-64 <strong>in</strong> Body Counts:<br />

Medical Quantification <strong>in</strong> Historical and Sociological Perspective, available as an<br />

electronic book through <strong>the</strong> library; Voltaire, Letters concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> English Nation,<br />

<strong>in</strong> Jacob, pp. 114-137, Lady Wortley Montagu, Letters, <strong>in</strong> Jacob, pp. 137-138,<br />

152-153.<br />

Questions: Why did people hesitate to <strong>in</strong>oculate? What methods did writers use to<br />

persuade <strong>the</strong> public? What is <strong>the</strong> broader significance <strong>of</strong> those methods?

October 31: Enlighten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> economy<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Bernard Mandeville, The Fable <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bees, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 242-254; François<br />

Quesnay, Physiocratic Formula, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 496-502; Adam Smith, On <strong>the</strong><br />

Wealth <strong>of</strong> Nations, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 505-515; Ken Alder, Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

Revolution, pp. 221-249, available via e-reserve.<br />

Questions: What makes economies grow, and what should be done to foster that<br />

growth? How did new ideas about <strong>in</strong>terchangeability and division <strong>of</strong> labor<br />

revolutionize <strong>in</strong>dustry?<br />

November 5: Government<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: John Locke, Second Treatise, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 395-404; Jean-Jacques<br />

Rousseau, Social Contract, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 430-441; Thomas Pa<strong>in</strong>e, Common<br />

Sense, <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 442-448; Frederick <strong>the</strong> Great, “Benevolent Despotism,”<br />

<strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 452-459; Immanuel Kant, “What is <strong>Enlightenment</strong>?” <strong>in</strong><br />

Kramnick, pp. 202-208.<br />

Questions: What separates a legitimate government from an illegitimate one? Us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Locke, Rousseau, and Pa<strong>in</strong>e, can you tell a story <strong>of</strong> change over time? How do<br />

all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se authors def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> ideal relationship between <strong>Enlightenment</strong> and<br />

government?<br />

November 7: Smuggl<strong>in</strong>g slander<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Robert Darnton, “The High <strong>Enlightenment</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Low Life <strong>of</strong> Literature <strong>in</strong><br />

Pre-Revolutionary France,” Past and Present (1971) Vol. 51, No. 1, pp. 81-115,<br />

available via JSTOR; Memoirs <strong>of</strong> Madame <strong>the</strong> Comtesse du Barry, pp. 337-389,<br />

available via e-reserve.<br />

Questions: What is <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> Grub Street? How damag<strong>in</strong>g would a<br />

publication like <strong>the</strong> Memoirs be? How would you assess its impact?<br />

November 12: Peer review workshop for paper #2<br />

November 14: Paper #2 due. In-class view<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Beaumarchais l’<strong>in</strong>solent<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: None<br />

Part IV: Translat<strong>in</strong>g Ideas <strong>in</strong>to Social Reality<br />

November 19: The meter: a revolutionary measurement<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Ken Alder, Measure <strong>of</strong> All Th<strong>in</strong>gs, pp. 1-67.<br />

Questions: Why <strong>the</strong> meter? Why dur<strong>in</strong>g a Revolution?<br />

November 21: Thanksgiv<strong>in</strong>g break<br />

November 26: The meter and <strong>the</strong> Terror<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Ken Alder, Measure <strong>of</strong> All Th<strong>in</strong>gs, pp. 69-105, 125-159.<br />

Questions: What obstacles did our <strong>in</strong>trepid astronomers face, and what does that tell<br />

you about <strong>the</strong> practice <strong>of</strong> science at this time? Summary <strong>of</strong> Alder due.<br />

November 28: The mistake that is <strong>the</strong> meter<br />

**Draft**

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Ken Alder, Measure <strong>of</strong> All Th<strong>in</strong>gs, pp. 291-350.<br />

Question: What is <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “hidden error” mentioned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> book’s title?<br />

December 3: Pacifism and total war<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>g: Benjam<strong>in</strong> Frankl<strong>in</strong>, “There was never…” <strong>in</strong> Kramnick, pp. 550-551;<br />

Immanuel Kant, “Perpetual Peace,” pp. 552-559; David Bell, The First Total<br />

War, pp. 52-83, available via e-reserve. Summary <strong>of</strong> Bell due.<br />

Question: What is <strong>the</strong> relationship between pacifism and total war?<br />

December 5: Review session for f<strong>in</strong>al exam<br />

**Draft**<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al exam will be due via email on December 14 at noon.