Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull FAR HORIZONS

Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull FAR HORIZONS

Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull FAR HORIZONS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Maritime</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Centre</strong>, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong><br />

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War<br />

Three generations <strong>of</strong> eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth | Robb Robinson

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

Herbert Johnson was born in <strong>Hull</strong> in 1890. He was the son <strong>of</strong> John Henry Johnson<br />

and his wife Charlotte (nee Menzies). His father, John, was a native <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> but<br />

Charlotte, his mother, hailed from South Queensferry, near Edinburgh. The two had<br />

married at Holy Trinity Church in 1877 and Herbert was their youngest son. John<br />

Johnson became a trawler skipper and worked on sailing smacks on the North Sea<br />

fishing grounds. He skippered a variety <strong>of</strong> smacks during the 1880s and the first half<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 1890s and the Johnson family, who lived <strong>of</strong>f Hessle Road, were fairly<br />

prosperous by the standards <strong>of</strong> the day.<br />

Everything changed for the Johnsons with the onset <strong>of</strong> winter 1893. On the 14 th<br />

November John Johnson took the smack Pallas out to the North Sea fishing<br />

grounds. The vessel appears to have been seen as late as the 20 th November but<br />

after that there was nothing. The Pallas and its crew were never seen again: the<br />

fishing smack was believed to have foundered in rough seas.<br />

Charlotte Johnson was left a widow at thirty six with eight young children and little in<br />

the way <strong>of</strong> savings to fall back on. She had been poorly educated - being unable to<br />

sign her marriage certificate - but was in good health and determined to try and keep<br />

her family together. Benefits in those days were paid by the local parish poor law<br />

union and extremely meagre. Each week she received no more than five loaves and<br />

three shillings and sixpence from the poor law union workhouse. After paying two<br />

shillings and sixpence a week rent for a very modest terrace house in Manchester<br />

Street <strong>of</strong>f Hessle Road, she was left with just one shilling to feed and cloth the<br />

children for seven days. To make ends meet she took in washing and ironing.<br />

Without modern appliances such work was a long hard drudge and paid poorly. She<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten washed from seven in the morning and was sometimes still ironing after nine in<br />

the evening: hard work but her aims were to survive, to keep all together until the<br />

older children could start to contribute to the family income. But eventually, things<br />

became so desperate that she had to put one <strong>of</strong> the boys in the orphanage until he<br />

was old enough to work. It’s difficult to imagine just how heartbreaking such a<br />

decision must have been.<br />

But Charlotte Johnson and her family proved resilient and they scraped through<br />

these worst <strong>of</strong> years. The girls earned their keep by taking jobs as domestic servants<br />

as soon as they were old enough, although their weekly wage <strong>of</strong> little more than half<br />

a crown meant they were unable to contribute much to family income. It was initially<br />

decided that Herbert’s eldest brother, Billy, would take up an apprenticeship as a<br />

whitesmith but after a few months at the job he decided he could earn good money<br />

for his family more quickly if he went fishing. He took his first trip out <strong>of</strong> St Andrew’s<br />

Dock as a cook but was sacked when the vessel returned. Undaunted, he joined a<br />

steam trawler as a fireman/trimmer, his job to stoke the boilers and to level the coal<br />

in the bunkers thus keeping the ship on an even keel. Later, he sailed as a deckhand<br />

and soon progressed through the crew becoming a skipper when only twenty three<br />

years old. He joined the new Hellyer boxing fleet and became one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

popular figures on St Andrew’s Dock in the years leading up to the Great War.<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 2

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

(Image from the Christopher Ketchell Local History Unit Collection)<br />

His younger brother Herbert took a couple <strong>of</strong> summer pleasure trips on trawlers with<br />

his uncle when just twelve and thirteen years old. Almost as soon as he was fourteen<br />

he hung around the lockhead at St Andrew’s Dock waiting for a ship short <strong>of</strong> crew.<br />

His opportunity came quickly: he signed aboard a trawler leaving the dock without an<br />

experienced fireman/trimmer. It was possibly on this trip, as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong>’s famous<br />

Gamecock Boxing Fleet, that he witnessed the Russian warships open fire on the<br />

unarmed <strong>Hull</strong> trawlers on the night <strong>of</strong> the 21st October 1904, in the mistaken belief<br />

that they were Japanese torpedo boats. Russia and Japan were at war and the<br />

vessels <strong>of</strong> the Russian Baltic fleet were at the early stages <strong>of</strong> a long voyage to the<br />

Far East. This incident became known as the North Sea Outrage or the Dogger Bank<br />

Incident and for a moment it seemed that Britain would be plunged into war with<br />

Russia. The Russian Government expressed their regrets and the fleet sailed on but<br />

to destruction. Many vessels in the Russian fleet were eventually destroyed by their<br />

Japanese foes under Admiral Togo at the Battle <strong>of</strong> Tsushima in 1905. One survivor<br />

<strong>of</strong> both the Dogger Bank Incident and the Battle <strong>of</strong> Tsushima is the cruiser Aurora,<br />

moored today at St Petersburg, and now remembered more for its role in the<br />

Russian Revolution in October 1917. In <strong>Hull</strong> a statue at the corner <strong>of</strong> The Boulevard<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 3

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

and Hessle Road commemorates the incident and the three <strong>Hull</strong> trawlermen who lost<br />

their lives through the action.<br />

A postcard showing an artist's impression <strong>of</strong> the shelling <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Hull</strong>'s Gamecock Fleet by the Russian Baltic Fleet<br />

(From the Christopher Ketchell Local History Unit Collection)<br />

The Memorial Statue at the corner <strong>of</strong> the Boulevard and<br />

Hessle Road which still stands in the same place today<br />

(From the Christopher Ketchell Local History Unit Collection)<br />

After this brief foray afloat Herbert came ashore for a while but this had little to do<br />

with the Russian Warships. Although he had given his best during his first weeks at<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 4

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

sea, as a small fourteen year boy, Herbert was still not really physically mature<br />

enough to shovel around 150 tons <strong>of</strong> coal consumed by a trawler’s furnaces during a<br />

five week boxing fleet voyage. Afterwards, he spent a short time working on the ‘Cod<br />

Farm’ helping to process salt dried fish for the overseas market but he returned to<br />

sea soon after his sixteenth birthday. Like Billy, he rose rapidly through the crew and<br />

made skipper in 1912 at the age <strong>of</strong> twenty two. As their fishing careers prospered,<br />

both brothers made good money providing crucial support for their widowed mother<br />

and siblings. The family moved from a poor terrace house in Manchester Street to<br />

better property further down Hessle.Road. Soon Herbert was courting strongly and<br />

made plans to marry Eva Wooldridge, a maid with a fish merchant’s family who lived<br />

down the Boulevard.<br />

Soon the two brothers were both skippers in the same trawling company. They both<br />

sailed with the Hellyer Boxing fleet, the steam trawler Viola – mentioned elsewhere<br />

on the website – was another <strong>of</strong> the company’s vessels. These boxing fleet trawlers<br />

didn’t bring their boxes <strong>of</strong> fish back to <strong>Hull</strong> but transferred them to steam cutters<br />

which ran them directly to London’s Billingsgate Market. All Hellyer ships were<br />

named after Shakespearian characters and in late1913 Billy was skipper <strong>of</strong> the<br />

trawler Angus whilst Herbert was master <strong>of</strong> the Bonar. On the 17 th November the two<br />

ships came alongside each other out on the fishing grounds. The brothers<br />

exchanged greetings and Billy, who was running low on fuel and anxious to make a<br />

start for home rather than wait for next morning’s Billingsgate cutter, transferred his<br />

fish boxes to Herbert’s trawler It was the last time they saw each other. As soon as<br />

the fish was transferred Billy Johnson turned his trawler for home. That evening the<br />

weather deteriorated and the wind reached almost hurricane proportions. The Angus<br />

was never seen again. Billy Johnson and his crew had disappeared, claimed by the<br />

North Sea; almost exactly twenty years after his father’s smack had gone missing<br />

Billy’s tragic loss was taken heavily by the family. Herbert was especially affected<br />

and gave up the sea for some months, also postponing his marriage until 1915.<br />

However, the money was too good to miss and he had returned as a Hellyer skipper<br />

by the time war with Germany broke out in August 1914. The immediate impact on<br />

the fishing fleets was a suspension <strong>of</strong> all operations. Herbert had been fishing with<br />

the Hellyer fleet when a radio message was relayed out to the one vessel with the<br />

fleet with a radio that all ships were to return to port. When the vessels returned to<br />

port a number were requisitioned by the Admiralty and fitted out as either<br />

minesweepers or armed patrol vessels and the remainder were allowed back to sea<br />

after a few weeks <strong>of</strong> inactivity but under strict Admiralty guidelines. The remaining<br />

boxing fleet vessels tried their luck <strong>of</strong>f the west coast <strong>of</strong> Scotland for a while but soon<br />

returned to <strong>Hull</strong> and all the trawlers went fishing on their own. Herbert Johnson was<br />

one <strong>of</strong> these skippers and was expected to keep within designated boundaries set by<br />

the Admiralty. Many trawler skippers, however, remained a law unto themselves<br />

however and Herbert was no exception. On one occasion he continued out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Humber and <strong>of</strong>f to the fishing grounds when all trawlers had been called back<br />

because a German battlecruiser squadron under Admiral Von Hipper had<br />

bombarded Whitby, Scarborough and Hartlepool, on another occasion he sailed well<br />

beyond the designated protection areas to the so-called C<strong>of</strong>fee grounds in search <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 5

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

a good catch. In this early part <strong>of</strong> the war he might not have been put <strong>of</strong>f by fear <strong>of</strong><br />

the Germans but was certainly more deterred by the threat <strong>of</strong> suspension – and thus<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> earnings - when his latter transgression was discovered. Afterwards he<br />

usually fished within the Admiralty designated boxes.<br />

Following the rules might have kept him out <strong>of</strong> trouble with the Admiralty but not with<br />

the Germans. In February 1915 the Germans embarked on their so-called restricted<br />

U-boat campaign against commerce at sea. At first they concentrated on merchant<br />

ships but by May they had turned to fishing vessels and Herbert Johnson’s trawlers<br />

were to be amongst their earliest victims. Late in the afternoon <strong>of</strong> the 3 rd May 1915,<br />

Herbert was conducting trawling operations from the bridge <strong>of</strong> the Hellyer trawler,<br />

Hector far out in the North Sea. His little ship was some 160 miles East North East <strong>of</strong><br />

Spurn Point. Two other trawlers, the Coquet and the Progress were also working in<br />

the vicinity. As the Hector’s crew were shooting the trawl they spotted a strange<br />

looking craft leaving the Coquet and heading for the Progress. As Johnson scanned<br />

the seas with his glasses the sound <strong>of</strong> gunfire drifted over the water and all aboard<br />

the Hector realised to their dismay that the mystery craft was a U-boat. It turned out<br />

later that the U-boat had halted the Coquet, ordered the crew to take to their open<br />

boat and row across to the submarine. Whilst they were lined up on deck under<br />

guard the German sailors rowed back to the trawler and set explosive charges.<br />

Whilst this was happening the U-boat set <strong>of</strong>f after the Progress which was attempting<br />

to get away. The Coquet’s crew were still on the deck and the reluctant passengers<br />

were forced to cling on grimly to the lifelines on the U-boats deck as the water<br />

swirled up to their waists. The Progress eventually hove to after four shots were<br />

fired. Explosive charges on both trawlers were duly detonated and their crews<br />

ordered to row <strong>of</strong>f in their open boats. Now the U-boat turned towards Herbert<br />

Johnson’s Hector.<br />

By the time those on the Hector realised what was happening, their vessel was a<br />

sitting duck, unable to flee with her trawl still down. The Germans were soon<br />

alongside and all aboard were ordered to row across to the U-boat. Now it was the<br />

turn <strong>of</strong> the Hector’s crew to line up on the submarine’s deck whilst the Germans used<br />

the rowing boat to inspect their unfortunate trawler. The inspection was soon over<br />

and the Hector’s crew were soon ordered back on board their rowing boat and told<br />

they would find fellow fishermen some way to the eastward. But that was not quite<br />

all: as the <strong>Hull</strong> trawlermen prepared to row away the German Commander passed<br />

some loaves over the side. German war bread, he said, two-thirds potatoes. As they<br />

rowed clear the U-boat sank the Hector with gunfire and then submerged. Herbert<br />

Johnson and his crew were left alone in their rowing boat far out in the North Sea:<br />

alone, but not quite empty handed. The Germans had put an oilskin in the bottom <strong>of</strong><br />

the boat, wrapped inside was a kettle full <strong>of</strong> hot water and all the food <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

trawler’s table, fried fish, cheese and jam, even some mugs. The cook had been<br />

preparing the evening meal and the Germans had scooped up everything he had laid<br />

on the table: a remnant <strong>of</strong> chivalry amongst an age <strong>of</strong> modern warfare.<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 6

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

The crew spent an unpleasant night in the little boat but were picked up by another<br />

trawler the next morning and all landed safely at Grimsby. By now the U-boat attacks<br />

on fishing vessels had intensified and before the month was out a total <strong>of</strong> fifteen <strong>Hull</strong><br />

trawlers were sunk in a similar fashion and more followed in June. The North Sea<br />

was proving too dangerous to work and the owners began sending all <strong>of</strong> their<br />

trawlers – even those design to work solely in the North Sea - to the distant water<br />

grounds <strong>of</strong>f Iceland and amongst those who made the voyage north was Herbert<br />

Johnson. In July 1915 he took the Cassio to Iceland. Neither the trawler nor the<br />

skipper had been to such waters before and they took with them a pilot, an<br />

experienced distant water trawlerman, to show them the grounds. At first, all went<br />

well and the little Cassio soon caught all the fish she could carry and began her<br />

voyage back to <strong>Hull</strong>. The first few days were uneventful but everything changed<br />

when Cassio’s crew spotted a large steamer on fire with what seemed like a U-boat<br />

at either end. The Cassio tried to get away, gathering steam and running south at top<br />

speed, but a U-boat was already in pursuit. A grim chase ensued: after an hour the<br />

U-boat had closed sufficiently to fire a shot but still the plucky little trawler tried to get<br />

away. An hour later and the U-boat was so close that the trawlermen could pick out<br />

the Germans in the conning tower. Still Herbert Johnson kept the engines running at<br />

top speed but the gap continued to narrow and as soon as the U-boat was in hailing<br />

distance its commander ordered the fishermen to leave their trawler. At this stage<br />

the Cassio’s crew didn’t need telling twice. They threw their boat overboard and had<br />

just got clear when the U-boat began shelling the Cassio. Within fifteen minutes the<br />

stricken trawler had sank and the U-boat had slipped beneath the waves without any<br />

further communications. For the second time in less than two months Herbert<br />

Johnson was alone with his crew in an open boat far out to sea.<br />

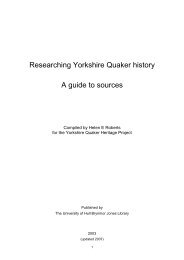

The Hellyer Trawler Cassio, sister ship to the Viola which was sunk by<br />

a German U-boat in July 1915 when skippered by Herbert Johnson.<br />

(Taken from a glass plate negative courtesy <strong>of</strong> Jon Grobler)<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 7

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

After pulling at their oars for six hours they spotted a sailing ship and scrambled<br />

aboard. The vessel was en route to Lerwick and during the six day voyage there it<br />

picked up another three trawler crews. Undaunted by his experience, Herbert<br />

Johnson returned to sea almost as soon as he returned to <strong>Hull</strong> but had at first to sail<br />

as a mate because Hellyers had lost so many trawlers. Later that year he and Eva<br />

were married at the Church <strong>of</strong> St Mary and St Peter in Dairycoates. They<br />

subsequently had six children.<br />

Later in the war Herbert entered Admiralty service and, like others before him,<br />

became skipper <strong>of</strong> a requisitioned Scottish drifter in the Western Mediterranean and<br />

Adriatic, being based at Mudros in Greece and Taranto in Italy amongst other<br />

places. Like many trawlermen in Admiralty service he had a sometimes strained<br />

relationship with Royal Navy discipline and had one <strong>of</strong> these brushes with authority<br />

whilst at Taranto. Here, Herbert was sent out with a shore patrol one evening to<br />

round up ratings who had reportedly been drinking too much. It turned into a case <strong>of</strong><br />

gamekeeper turned poacher as Herbert and his patrol came across a group <strong>of</strong> other<br />

<strong>Hull</strong> trawler skippers and their crews in the local bars they searched. Stopping for a<br />

drink they soon ended up much the worse for wear themselves and certainly in no fit<br />

state to round anyone else up.<br />

Herbert and his armed drifter later joined one <strong>of</strong> the first hydrophone flotillas<br />

operating in this theatre <strong>of</strong> the war but after hostilities ceased he returned to Britain<br />

overland by train and was sent up to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. He was<br />

there when the great battleships <strong>of</strong> the German High Seas fleet were scuttled by<br />

their crews at their moorings in June 1919. More than 400,000 tons worth <strong>of</strong><br />

warships went to the bottom and represents the largest ever loss <strong>of</strong> shipping in one<br />

day.<br />

The Hindenburg, part <strong>of</strong> the German High Seas Fleet scuttled at Scapa Flow in 1919<br />

(Source http://www.firstworldwar.com/photos/sea3.htm)<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 8

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

After demobilisation, Herbert Johnson returned to trawling and to Hellyers and during<br />

the 1920s voyaged to Iceland, Bear Island and the White Sea. However, he later fell<br />

out with Hellyers and during the 1930s found it more difficult to get a ship, at one<br />

time going for up to eighteen months without a trip and as he got older he sometimes<br />

sailed as mate or skippered old trawlers for their last voyage to scrapyards on the<br />

Continent. One way or the other he survived and by the Second World War was<br />

working as an electrician’s mate for Brigham and Cowan Ltd., ship repairers. The<br />

sea had not finished with the Johnsons, however: in December 1939 Eric Johnson,<br />

Herbert’s son and Charlotte’s grandson who joined the patrol Service was lost on the<br />

Loch Doon which was mined <strong>of</strong>f Blyth in Northumberland in December 1939. He was<br />

only nineteen and is remembered on the Sparrow’s Nest Memorial at Lowest<strong>of</strong>t,<br />

along with many other <strong>Hull</strong> trawlermen who gave their lives in the Patrol Service<br />

during the Second World War. The North Sea had taken the eldest son from each <strong>of</strong><br />

three generations <strong>of</strong> the Johnson family.<br />

Charlotte Johnson, meanwhile, had finished bringing up her children and lived on<br />

until 1929 when she died in Hessle aged 73. Despite her family’s deprivations many<br />

<strong>of</strong> her children and grandchildren went on to rewarding and fulfilled lives and today<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the descendants are scattered across the globe as far afield as Vancouver<br />

and New Zealand. Herbert himself retired in the 1950s and, although his eyesight<br />

increasingly deteriorated, he lived on until 1978. His story, like so many others, might<br />

have been forgotten had not his son, Phil, given him a tape recorder and tapes with<br />

which to recall in absorbing detail the remarkable life <strong>of</strong> the Johnson family and their<br />

struggles with the sea.<br />

Robb Robinson February 2009.<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 9

Charlotte Johnson’s Struggle: Herbert Johnson’s War - Three generations <strong>of</strong><br />

eldest sons lost to the North Sea<br />

Select Bibliography<br />

Alec Gill, Lost Trawlers <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hull</strong> 1835 – 1987 (UK: Hutton Press, 1989.<br />

Robb Robinson and Ian B. Hart, ‘Viola/Dias: The Working Life and Contexts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Steam Trawler/Whaler and Sealer’ in Mariner’s Mirror, (August 2003).<br />

Robb Robinson, Trawling: The Rise and Fall <strong>of</strong> the British trawl fishery (UK:<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Exeter Press, 1996).<br />

On-line References<br />

www.viola-dias.org<br />

Viola website<br />

Thanks also to Phil Johnson for access to Herbert Johnson’s taped reminiscences<br />

<strong>FAR</strong> <strong>HORIZONS</strong> – to the ends <strong>of</strong> the Earth Page 10