Download this publication as PDF - WQLN

Download this publication as PDF - WQLN

Download this publication as PDF - WQLN

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

home & garden<br />

MAYBE IT’S THE thrill of underground<br />

tunnels, daring escapes, and border crossings<br />

that gets our adrenaline going. Or maybe<br />

it’s a tinge of shame and sorrow, mixed with<br />

wishful thinking. We’d like to believe that our<br />

ancestors, when faced with a person or family<br />

in need, came to the rescue of freedom seekers<br />

before, during and after the Civil War, hiding<br />

them in an old stone b<strong>as</strong>ement.<br />

But the Underground Railroad w<strong>as</strong> neither<br />

underground nor a railroad, and like most<br />

myth and folklore, there’s more to the story<br />

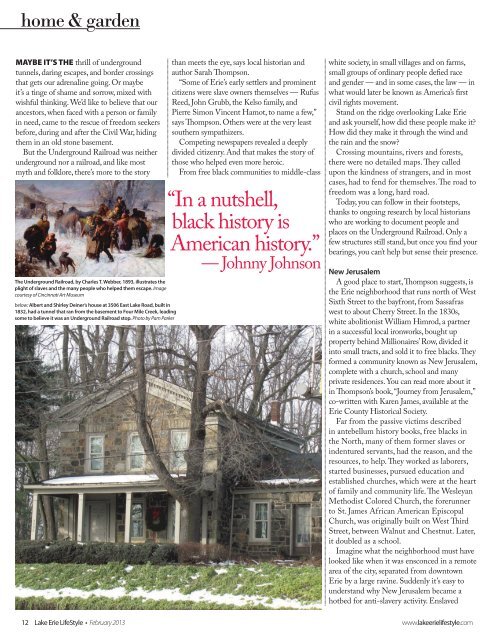

The Underground Railroad, by Charles T. Webber, 1893, illustrates the<br />

plight of slaves and the many people who helped them escape. Image<br />

courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum<br />

below: Albert and Shirley Deiner’s house at 3506 E<strong>as</strong>t Lake Road, built in<br />

1832, had a tunnel that ran from the b<strong>as</strong>ement to Four Mile Creek, leading<br />

some to believe it w<strong>as</strong> an Underground Railroad stop. Photo by Pam Parker<br />

February2013<br />

than meets the eye, says local historian and<br />

author Sarah Thompson.<br />

“Some of Erie’s early settlers and prominent<br />

citizens were slave owners themselves — Rufus<br />

Reed, John Grubb, the Kelso family, and<br />

Pierre Simon Vincent Hamot, to name a few,”<br />

says Thompson. Others were at the very le<strong>as</strong>t<br />

southern sympathizers.<br />

Competing newspapers revealed a deeply<br />

divided citizenry. And that makes the story of<br />

those who helped even more heroic.<br />

From free black communities to middle-cl<strong>as</strong>s<br />

“In a nutshell,<br />

black history is<br />

American history.”<br />

— Johnny Johnson<br />

white society, in small villages and on farms,<br />

small groups of ordinary people defied race<br />

and gender — and in some c<strong>as</strong>es, the law — in<br />

what would later be known <strong>as</strong> America’s first<br />

civil rights movement.<br />

Stand on the ridge overlooking Lake Erie<br />

and <strong>as</strong>k yourself, how did these people make it?<br />

How did they make it through the wind and<br />

the rain and the snow?<br />

Crossing mountains, rivers and forests,<br />

there were no detailed maps. They called<br />

upon the kindness of strangers, and in most<br />

c<strong>as</strong>es, had to fend for themselves. The road to<br />

freedom w<strong>as</strong> a long, hard road.<br />

Today, you can follow in their footsteps,<br />

thanks to ongoing research by local historians<br />

who are working to document people and<br />

places on the Underground Railroad. Only a<br />

few structures still stand, but once you find your<br />

bearings, you can’t help but sense their presence.<br />

New Jerusalem<br />

A good place to start,Thompson suggests, is<br />

the Erie neighborhood that runs north of West<br />

Sixth Street to the bayfront, from S<strong>as</strong>safr<strong>as</strong><br />

west to about Cherry Street. In the 1830s,<br />

white abolitionist William Himrod, a partner<br />

in a successful local ironworks, bought up<br />

property behind Millionaires’Row, divided it<br />

into small tracts, and sold it to free blacks.They<br />

formed a community known <strong>as</strong> New Jerusalem,<br />

complete with a church, school and many<br />

private residences. You can read more about it<br />

in Thompson’s book,“Journey from Jerusalem,”<br />

co-written with Karen James, available at the<br />

Erie County Historical Society.<br />

Far from the p<strong>as</strong>sive victims described<br />

in antebellum history books, free blacks in<br />

the North, many of them former slaves or<br />

indentured servants, had the re<strong>as</strong>on, and the<br />

resources, to help. They worked <strong>as</strong> laborers,<br />

started businesses, pursued education and<br />

established churches, which were at the heart<br />

of family and community life. The Wesleyan<br />

Methodist Colored Church, the forerunner<br />

to St. James African American Episcopal<br />

Church, w<strong>as</strong> originally built on West Third<br />

Street, between Walnut and Chestnut. Later,<br />

it doubled <strong>as</strong> a school.<br />

Imagine what the neighborhood must have<br />

looked like when it w<strong>as</strong> ensconced in a remote<br />

area of the city, separated from downtown<br />

Erie by a large ravine. Suddenly it’s e<strong>as</strong>y to<br />

understand why New Jerusalem became a<br />

hotbed for anti-slavery activity. Enslaved<br />

www.lakeerielifestyle.com