Albertopolis Walking Tour: transcript - Royal Institute of British ...

Albertopolis Walking Tour: transcript - Royal Institute of British ...

Albertopolis Walking Tour: transcript - Royal Institute of British ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

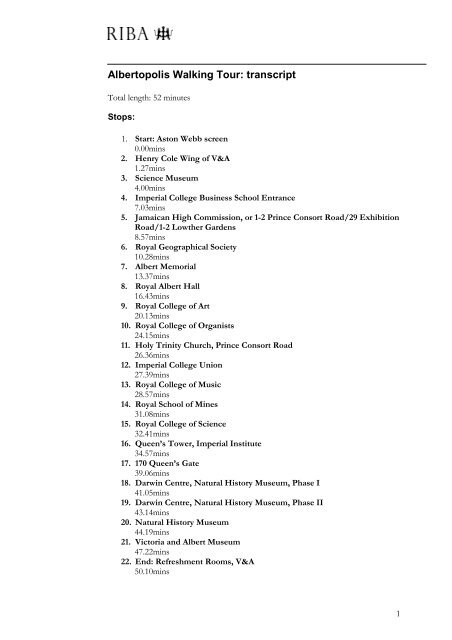

<strong>Albertopolis</strong> <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>Tour</strong>: <strong>transcript</strong><br />

Total length: 52 minutes<br />

Stops:<br />

1. Start: Aston Webb screen<br />

0.00mins<br />

2. Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> V&A<br />

1.27mins<br />

3. Science Museum<br />

4.00mins<br />

4. Imperial College Business School Entrance<br />

7.03mins<br />

5. Jamaican High Commission, or 1-2 Prince Consort Road/29 Exhibition<br />

Road/1-2 Lowther Gardens<br />

8.57mins<br />

6. <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society<br />

10.28mins<br />

7. Albert Memorial<br />

13.37mins<br />

8. <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall<br />

16.43mins<br />

9. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

20.13mins<br />

10. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists<br />

24.15mins<br />

11. Holy Trinity Church, Prince Consort Road<br />

26.36mins<br />

12. Imperial College Union<br />

27.39mins<br />

13. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music<br />

28.57mins<br />

14. <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines<br />

31.08mins<br />

15. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science<br />

32.41mins<br />

16. Queen’s Tower, Imperial <strong>Institute</strong><br />

34.57mins<br />

17. 170 Queen’s Gate<br />

39.06mins<br />

18. Darwin Centre, Natural History Museum, Phase I<br />

41.05mins<br />

19. Darwin Centre, Natural History Museum, Phase II<br />

43.14mins<br />

20. Natural History Museum<br />

44.19mins<br />

21. Victoria and Albert Museum<br />

47.22mins<br />

22. End: Refreshment Rooms, V&A<br />

50.10mins<br />

1

1. Start: Exhibition Road Entrance to Victoria and Albert<br />

Museum – Aston Webb screen<br />

0.00mins<br />

To begin our tour <strong>of</strong> the Exhibition<br />

Road Cultural Quarter we start at the<br />

southern end <strong>of</strong> Exhibition Road,<br />

outside the Groups Entrance to the<br />

V&A.<br />

The low-level building you see before<br />

you is quite literally a link between<br />

science and art, a fitting way to start<br />

our tour <strong>of</strong> <strong>Albertopolis</strong>. One <strong>of</strong><br />

Prince Albert’s intentions for the area<br />

was the encouragement <strong>of</strong> the study <strong>of</strong><br />

both the arts and science. The<br />

structure in front <strong>of</strong> you is effectively a<br />

screen, designed by the architect Sir<br />

Aston Webb screen, 2010<br />

Aston Webb, which joins the Victoria<br />

Photographer: Susan Pugh<br />

and Albert Museum, an internationally<br />

renowned arts collection on the right,<br />

with the former Science Schools<br />

building on the left, (now the Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> the V&A).<br />

The screen was erected in 1909 to hide the original boiler house <strong>of</strong> the museum which lay<br />

behind. Such an industrial space wasn’t suitable or attractive enough for Exhibition Road, so<br />

Webb was commissioned to design something to mask it from view. Although relatively<br />

small the Classical screen he created is effective and imposing, with its square Corinthian<br />

columns above a heavy-looking rusticated base. The solidity <strong>of</strong> this base is emphasised by the<br />

many pockmarks you see along it, all resulting from bomb damage during the Second World<br />

War.<br />

Turning to the left or northwards up Exhibition Road, we now look to the Henry Cole Wing<br />

<strong>of</strong> the V&A, or the former Science Schools.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

2

2. Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> V&A<br />

1.27mins<br />

To the north or left <strong>of</strong> where we are standing<br />

is a striking Italianate red brick building now<br />

known as the Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> the V&A. It<br />

has had many different names since it was<br />

built in 1871, including the Science Schools,<br />

the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science, and the Huxley<br />

Building. It was originally built as a School <strong>of</strong><br />

Naval Architecture, to contain laboratories and<br />

teaching rooms.<br />

The initial plans for the building were made by<br />

Francis Fowke, however he died before work<br />

began. General H.D.Y. Scott, who also<br />

worked on the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall, took over<br />

the project and completed the building with<br />

the assistance <strong>of</strong> James Gamble and J.W. Wild.<br />

This was the first building <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Science and Art to have a prominent<br />

position on Exhibition Road, so a showy front was required. Scott designed an impressive<br />

seven-bay elevation with one-bay projections at either end topped with a pediment. Red<br />

brick and lots <strong>of</strong> terracotta decoration ornamented in Minton majolica were used, following<br />

the style evolved by Cole, Fowke and Sykes at the South Kensington Museum.<br />

An elaborate decorative scheme was devised, based on Sykes’ decoration <strong>of</strong> the museum’s<br />

Lecture Theatre building, (now the north wing <strong>of</strong> the Madejski Gardens). The terracotta<br />

columns on the ground floor exterior are identical to those on the Lecture Theatre front. On<br />

the top floor <strong>of</strong> the building are more ornate columns, producing a long open arcaded<br />

balcony or loggia.<br />

In 1974 the building was converted to house the Department <strong>of</strong> Prints, Drawings &<br />

Photographs <strong>of</strong> the V&A and renamed the Henry Cole Building. A new link structure was<br />

built to join it to the museum, whilst also creating a new entrance on Exhibition Road.<br />

Before we leave this side <strong>of</strong> the Exhibition Road it’s worth noting the traditional red<br />

telephone kiosk between the Aston Webb screen and the Henry Cole Wing. This iconic<br />

telephone box design, known as the K2 type, was created by Giles Gilbert Scott in 1927, and<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the drawings for it now in the RIBA Drawings and Archives Collections.<br />

Interestingly Scott was the grandson <strong>of</strong> Sir George Gilbert Scott, the architect <strong>of</strong> the Albert<br />

Memorial. All surviving original red telephone boxes are now listed buildings, and as such are<br />

part <strong>of</strong> our protected heritage.<br />

Turn to face the other side <strong>of</strong> Exhibition Road to view the large, Classical stone building<br />

opposite, the Science Museum.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

Henry Cole Wing, 1871<br />

Reproduced by permission <strong>of</strong> English<br />

Heritage. NMR<br />

3

3. Science Museum<br />

4.00mins<br />

The Science Museum is the youngest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

museums in the Exhibition Road Cultural<br />

Quarter, although its origins date back to the<br />

Great Exhibition <strong>of</strong> 1851. The study <strong>of</strong> science<br />

was a key part <strong>of</strong> the exhibition’s objective, and<br />

this ideal was continued by Prince Albert and<br />

the 1851 Commissioners when they developed<br />

the area <strong>of</strong> South Kensington.<br />

Although the first museum, the South<br />

Kensington Museum which opened in 1857, is<br />

though <strong>of</strong> as an arts institution, science<br />

collections featured in its very first building, the<br />

Brompton Boilers. As the science collections<br />

expanded during the 1860s they had to be<br />

gradually moved across Exhibition Road, in to<br />

storage in buildings originally constructed for<br />

the International Exhibition <strong>of</strong> 1862.<br />

The East Block <strong>of</strong> the Science<br />

Museum, 1928<br />

Copyright: Science Museum/SSPL<br />

From 1893 the science collections had their own director but they were still administered as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the South Kensington Museum. The science accommodation was by now inadequate<br />

and the scientific community argued for new and appropriate buildings.<br />

The committee planned a range <strong>of</strong> buildings all the way from Exhibition Road to Queen’s<br />

Gate. In reality only a small proportion <strong>of</strong> the proposed buildings were ever built.<br />

Construction work began on the East Block in 1913, and this is the building which you see<br />

before you today.<br />

Due to World War I the museum was not fully opened until 1928. It was designed by the<br />

Office <strong>of</strong> Works and the architect Sir Richard Allison (1869-1958). Allison, who was a<br />

Scotsman, used the department store as a model for the inside <strong>of</strong> the museum and the<br />

Edwardian <strong>of</strong>fice building for the outside. Having said that, the Science Museum’s exterior<br />

does also bear some resemblance to Selfridges on Oxford Street.<br />

Allison designed generous circulation spaces inside the museum, and a ro<strong>of</strong> lit central hall<br />

which serves very well for the display <strong>of</strong> large engines. He also created open galleries at the<br />

sides, lit naturally as was the fashion at the time.<br />

In 1996 some westward expansion at South Kensington finally began. The Wellcome Trust<br />

sponsored a new building which was to become the Wellcome Wing <strong>of</strong> the museum. This<br />

was opened by HM The Queen in June 2000 and houses exhibitions <strong>of</strong> present and future<br />

science and technology.<br />

If you cross over Exhibition Road to stand at the entrance to the Science Museum you’ll see<br />

on the opposite side <strong>of</strong> the road a striking modern church that is the Church <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ<br />

<strong>of</strong> Latter-Day Saints. This Mormon church was designed by T.P Bennett and Son in 1961.<br />

Also worth noting is the large block <strong>of</strong> flats immediately next door to the church, numbers<br />

59-63 Prince Gate. This is a 1930s interpretation <strong>of</strong> the white stuccoed terraces <strong>of</strong> South<br />

4

Kensington. This Art Deco building was completed in around 1935 by the architects Adie,<br />

Button and Partners.<br />

Continue northwards up Exhibition Road until you come to a contemporary building with<br />

tall white columns which is the main entrance to Imperial College.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

4. Imperial College Business School Entrance<br />

7.03mins<br />

This high-tech building was opened by Queen<br />

Elizabeth II in 2004 as the Tanaka Business<br />

School and it acts as the main entrance and<br />

atrium to Imperial College London. The<br />

£26million building costs were met by alumnus<br />

Dr Gary Tanaka, hence the building’s original<br />

name. In October 2008 the building was renamed<br />

the Imperial College Business School to<br />

emphasise the connection with the college.<br />

The structure was designed by Foster and<br />

Partners and gives Imperial College a very strong<br />

presence and identity on Exhibition Road. The<br />

dramatic white colonnade stands proudly forward<br />

on to the pavement, welcoming students in to the<br />

college. Through the glass façade you can see an<br />

impressive six-storey stainless steel drum, which<br />

contains six lecture theatres.<br />

The Business School connects on the upper floors with the neighbouring <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong><br />

Mines, a building designed by the Victorian architect Sir Aston Webb, which will be featured<br />

later in this walk. It also provides public access to other parts <strong>of</strong> Imperial College, acting as a<br />

thoroughfare to buildings behind, including the striking blue Faculty building, another<br />

structure designed by Foster and Partners.<br />

Lord Foster <strong>of</strong> Foster and Partners is the one <strong>of</strong> the most influential and prolific <strong>British</strong><br />

architects today. He has designed some <strong>of</strong> London’s most recent landmarks including the<br />

Greater London Assembly building and the gherkin-shaped Swiss Re tower.<br />

Looking across Exhibition Road to number 50 Princes Gate, you can see the London branch<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Goethe <strong>Institute</strong>, another <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> the Exhibition Road Cultural Group.<br />

The Goethe <strong>Institute</strong> acts to promote the study <strong>of</strong> Germany, its cultural, social and political<br />

life, and in particular its language.<br />

Continue up Exhibition Road until you reach Prince Consort Road. Pause here to look at<br />

the red brick building on the corner.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

Imperial College Business School, 2007<br />

Photographer: Christopher Hope-Fitch<br />

Copyright: Christopher Hope-<br />

Fitch/RIBA Library Photographs<br />

Collection<br />

5

5. Jamaican High Commission, or 1-2 Prince Consort Road/29<br />

Exhibition Road/1-2 Lowther Gardens<br />

8.57mins<br />

The Jamaican High Commission is now<br />

located here in this beautiful red brick<br />

building here on the corner <strong>of</strong> Prince<br />

Consort Road and Exhibition Road.<br />

Although not really part <strong>of</strong> the story <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Albertopolis</strong> it’s worth pausing here to<br />

admire this building which is a very<br />

important, relatively early example <strong>of</strong><br />

the Queen Anne style.<br />

The building was designed by J.J.<br />

Stevenson in 1876, as a pair <strong>of</strong> private<br />

houses. It is a superb example <strong>of</strong> this<br />

revival style <strong>of</strong> architecture. The name<br />

Queen Anne style is derived from its<br />

inspiration: that is English and Dutch<br />

houses in around 1700, when Queen<br />

Anne was on the throne. The houses<br />

display many <strong>of</strong> the style’s distinctive<br />

characteristics including: an irregular outline; asymmetric windows, balconies and gables; cutbrick<br />

decoration; superimposed pilasters; and the use <strong>of</strong> the sunflower motif. It is interesting<br />

to look from Stevenson’s redbrick building to the contrasting white stucco terraced houses<br />

across the road, showing just how far domestic architecture had developed from the<br />

Georgian style which had dominated from the 18 th century right up until the mid-19 th<br />

century.<br />

Continue up to the top <strong>of</strong> Exhibition Road, and turn left onto Kensington Gore, walk about<br />

ten metres along the road to look at another significant example <strong>of</strong> the Queen Anne Style,<br />

Lowther Lodge, now home to the <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

6. <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society<br />

10.28mins<br />

1-2 Prince Consort Road/29 Exhibition<br />

Road/1-2 Lowther Gardens<br />

Source: Building News, 1878<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Photographs<br />

Collection<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society was founded in 1830, and moved to Lowther Lodge in<br />

1912. Although not part <strong>of</strong> the 1851 Commissioners’ original plans for the area, the Society’s<br />

objectives and activities complement the ideals <strong>of</strong> South Kensington and it is now one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the Exhibition Road Cultural Group.<br />

Lowther Lodge was designed by the architect Richard Norman Shaw in 1873. It was to be a<br />

“country house” on the edge <strong>of</strong> town for the MP, William Lowther, who had bought the site<br />

in 1870 and pulled down the previous property.<br />

When Shaw’s design was exhibited at the <strong>Royal</strong> Academy in 1874 a contemporary journal,<br />

The Building News, declared it to be a house <strong>of</strong> the “most uncompromising Queen Anne<br />

6

character.” This was a new style <strong>of</strong> architecture <strong>of</strong> which Shaw and JJ Stevenson were the<br />

main proponents. Key characteristics <strong>of</strong> the style were the use <strong>of</strong> redbrick; asymmetrical<br />

elevations; tall pedimented or Dutch gables; towering chimney stacks; and the use <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sunflower motif. All <strong>of</strong> these features can be seen at Lowther Lodge.<br />

William Lowther died in 1912, and his son James, Speaker <strong>of</strong> the House <strong>of</strong> Commons, sold<br />

the house for £100,000 to the RGS.<br />

In 1928-30 the building was altered<br />

and extended to better suit the needs<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Society.<br />

To the left you can see the new<br />

lecture theatre, which was added by<br />

Kennedy and Nightingale on the site<br />

<strong>of</strong> the former stables for the<br />

property. The external wall they<br />

created on the corner <strong>of</strong> Kensington<br />

Gore and Exhibition Road is<br />

consequently very bare, with no<br />

windows, mainly for acoustic reasons.<br />

The only decorations to the wall are<br />

two statues <strong>of</strong> famous explorers: Sir<br />

Ernest Shackleton by C. Sargeant<br />

Jagger <strong>of</strong> 1932; and David<br />

Livingstone by TB Huxley-Jones, <strong>of</strong><br />

1953.<br />

Immediately to the west, or right <strong>of</strong> Lowther Lodge on Kensington Gore stands a very large,<br />

imposing redbrick block <strong>of</strong> flats. This is Albert Hall Mansions, built between 1879 and 86,<br />

and also designed by Shaw. When Lowther Lodge was built Kensington was almost fully<br />

developed, although the adjacent sites to the house were still empty. It is therefore surprising<br />

that it was Shaw himself who filled the site to the west with a structure which completely<br />

over-powers the house he designed. Perhaps this was a symptom <strong>of</strong> how many Victorian<br />

architects saw their creations as individual ventures, disregarding context.<br />

Albert Hall Mansions was the first block <strong>of</strong> flats in London in the new red brick Queen<br />

Anne style, many followed it, including several other large red brick mansion flats which<br />

grew up around the Albert Hall during the 1880s and 90s.<br />

Continue westward along Kensington Gore until you come to the traffic lights by the<br />

Albert Hall. Cross over the road here to enter Kensington Gardens, heading towards the<br />

Albert Memorial. Before we move on to the memorial, take the opportunity to turn around<br />

to get a better view <strong>of</strong> Albert Hall Mansions.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

Front and side elevations for Lowther Lodge,<br />

1873<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Drawings and<br />

Archives Collections<br />

7

7. Albert Memorial<br />

13.37mins<br />

The 53 metre high Albert Memorial has been a<br />

London landmark since its unveiling in 1872.<br />

Following the sudden death <strong>of</strong> her beloved Prince<br />

Albert from typhoid in 1861, Queen Victoria very<br />

quickly decided that a memorial should be built to<br />

honour her late husband. She invited seven leading<br />

architects to submit designs for a monument to be<br />

built in Kensington Gardens. It was to be located just<br />

to the north <strong>of</strong> the museums area which Albert had<br />

helped to build up, and to the west <strong>of</strong> where the<br />

Great Exhibition had been held.<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> the competition were announced in<br />

April 1863. George Gilbert Scott was the winner, with<br />

his ornate design for a canopy or tabernacle in the<br />

Gothic style, containing a seated statue <strong>of</strong> Albert.<br />

Work began on constructing the memorial in 1864<br />

and in 1872 the 176 feet or 53 metre high memorial<br />

was opened, although it was not completely finished<br />

until 1876. The monument cost £120,000 to build, a<br />

large sum at the time, due in part to the luxurious<br />

materials used and the numerous craftsmen involved.<br />

The 24ct gold statue <strong>of</strong> Albert was completed by the<br />

sculptor John Henry Foley. The prince is dressed as a<br />

Knight <strong>of</strong> the Garter and is sat holding a catalogue to<br />

the Great Exhibition <strong>of</strong> 1851. The memorial contains<br />

many references to Albert’s interests and his work in<br />

the field <strong>of</strong> arts and science education.<br />

At the base <strong>of</strong> the canopy runs a frieze in which is the<br />

following inscription:<br />

Statue <strong>of</strong> Prince Albert, preliminary<br />

model for the Albert Memorial,<br />

c.1863<br />

Copyright: V&A Images<br />

“Queen Victoria and her people - A tribute to the memory <strong>of</strong> Albert Prince Consort –<br />

As a Tribute <strong>of</strong> their gratitude – for a life dedicated to the public good.”<br />

The mosaics for each side <strong>of</strong> the canopy and beneath it were designed by Clayton and Bell<br />

and manufactured by the firm <strong>of</strong> Salviati in Venice.<br />

The podium <strong>of</strong> the memorial is surrounded by an elaborate sculptural frieze, depicting 169<br />

individual composers, architects, poets, painters, and sculptors, all carved by Henry Hugh<br />

Armstead and John Birnie Philip.<br />

At the four corners <strong>of</strong> the podium, below the statue <strong>of</strong> the prince, are allegorical marble<br />

sculptures <strong>of</strong> agriculture, commerce, engineering and manufacturing. At the outermost<br />

corners are allegorical stone sculptures <strong>of</strong> Europe, Asia, Africa, & the Americas, reflecting<br />

Albert’s international concerns.<br />

8

Underneath the memorial is a large undercr<strong>of</strong>t <strong>of</strong> numerous brick arches, which act as the<br />

foundations to the heavy monument above. <strong>Tour</strong>s <strong>of</strong> the memorial, including the undercr<strong>of</strong>t,<br />

are given by English Heritage on the first Sunday <strong>of</strong> the month, from March to December.<br />

If you were to continue walking northwards through the park you’d come to the Serpentine<br />

Gallery, one <strong>of</strong> London’s premier galleries for Contemporary Art, and one <strong>of</strong> the 16<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the Exhibition Road Cultural Group.<br />

For the next stop on our <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>Tour</strong> turn to the south, looking across Kensington Gore<br />

to the iconic round structure <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

8. <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall<br />

16.43mins<br />

Built between 1867 and 1871 the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

Albert Hall was originally intended to be<br />

both a large music hall and a conference<br />

centre for meetings <strong>of</strong> learned societies. In<br />

reality it was not possible to combine the<br />

two, however the range <strong>of</strong> events held in<br />

the hall as always been incredible. From<br />

opera to ice skating, rock concerts to<br />

awards events, the hall has become known<br />

as the “Nation’s Village Hall.”<br />

A music hall for South Kensington was<br />

first proposed by Prince Albert and Henry<br />

Cole in as early as 1853. The project later<br />

materialised as the Central Hall <strong>of</strong> Arts and<br />

Science, and a site to the north <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

Horticultural Society Gardens was<br />

proposed.<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall, 1970<br />

Photographer: Edwin Smith (1912-1971)<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Photographs<br />

Collection<br />

After the death <strong>of</strong> the Prince in 1861, Cole became the driving force behind the project. It<br />

was renamed the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall by Queen Victoria when she laid the foundation stone in<br />

May 1867.<br />

The hall was designed by Captain Francis Fowke and completed by Major-General Henry<br />

Scott after Fowke’s sudden death in 1865. Both were engineer designers closely associated<br />

with Cole and the South Kensington Museum. In general terms the hall’s overall form and<br />

internal layout can be attributed to Fowke, and its exterior look and character to Scott.<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall is an iconic modern day version <strong>of</strong> the Roman amphitheatre. The<br />

elliptical shape <strong>of</strong> the building was possibly modelled on the ancient amphitheatres <strong>of</strong> Nîmes<br />

and Arles, in the South <strong>of</strong> France, both <strong>of</strong> which were visited by Cole and Fowke in 1863.<br />

Scott simplified Fowke’s design, with less overt classical detailing. One major change he<br />

made was the addition <strong>of</strong> the mosaic frieze which continues all the way round the building<br />

9

elow the main cornice. Numerous artists contributed to the frieze design, including Reuben<br />

Townroe. In keeping with the ethos <strong>of</strong> <strong>Albertopolis</strong> the ladies <strong>of</strong> the South Kensington<br />

Museum’s mosaic class made the 800 slabs which make up the frieze.<br />

The main cylinder <strong>of</strong> the building is primarily red brick with terracotta decoration. Above is a<br />

vast domed ro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> glass and iron.<br />

On the 29 th March 1871 Queen Victoria <strong>of</strong>ficially opened the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall. It was to be<br />

an emotional and testing occasion for the Queen. She arrived by carriage on Kensington<br />

Gore, but had requested that the statue <strong>of</strong> her late husband, in the centre <strong>of</strong> the Albert<br />

Memorial, be covered in cloth so as not to upset her. Despite it being 10 years after her<br />

husband’s death she still wore black mourning dress, however she had white ribbons added<br />

to it to show that she was at least in part happy.<br />

10,000 people attended the opening, however the brick and terracotta structure was actually<br />

built to seat 8000. Due to current Health and Safety regulations today it seats just 5600. In<br />

2004 the hall underwent a £70million refurbishment. This included adding 3 new basement<br />

levels and loading bays, to reduce disruption to local residents due to the almost daily<br />

changing <strong>of</strong> events in this busy central London venue.<br />

To the right or west <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall on Kensington Gore is a very different large,<br />

modern building, the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art. Move to a position on Kensington Gore where<br />

you have a good view <strong>of</strong> the college.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

9. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art<br />

20.13mins<br />

The large modern building you see before<br />

you was built between 1960 and 1963 to be<br />

the new home <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten referred to simply as the RCA. It was<br />

designed by three members <strong>of</strong> its own<br />

staff: Henry Thomas Cadbury-Brown, who<br />

taught in the sculpture department; Sir<br />

Hugh Casson, then Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Interior<br />

Design; and Robert Gooden, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong><br />

Silversmithing and Jewellery.<br />

Just as with the V&A, the origins <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art came from the 1830s<br />

movement for popular education in<br />

industrial design. The RCA began life in<br />

Somerset House, central London, in 1837<br />

as the Metropolitan School <strong>of</strong> Design.<br />

Design for the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Art,<br />

c.1955-60<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Drawings and<br />

Archives Collections<br />

In 1857 it was renamed the Normal<br />

Training School <strong>of</strong> Art and moved to<br />

South Kensington, where it shared a site with the new South Kensington Museum. Another<br />

10

name change followed in 1863, before the college gained its current title, the <strong>Royal</strong> College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Art in 1897.<br />

By the early 20 th century the college was running out <strong>of</strong> space. Various proposals were put<br />

forward for a new building. In 1951 the site before you on Kensington Gore was assigned to<br />

the RCA. For the first time all the college departments and administration could be brought<br />

together on one site (although the RCA has since expanded and this is no longer possible).<br />

The design for the new building was not completed until 1959. The result is a striking<br />

structure, very much <strong>of</strong> the late 1950s/60s. It was a brave move for both the designers and<br />

Westminster Council, placing such an overtly modern structure amongst the Georgian white<br />

stuccoed terraces and the red brick Victorian buildings <strong>of</strong> Kensington. The RCA building<br />

was listed Grade II in 2001, recognising the building as a very fine example <strong>of</strong> a cultural<br />

institution <strong>of</strong> the 1960s.<br />

The college was planned as three blocks: the main eight-storey structure along Kensington<br />

Gore, known as the Darwin Building and named after the principal <strong>of</strong> the time, Robin<br />

Darwin; the Gulbenkian Wing, the long, low, exhibition block facing the Albert Hall; and<br />

behind it, a smaller block housing the library, and common-rooms. Although the new<br />

buildings are all strikingly different to the neighbouring Victorian structures, the designers<br />

took care to be as complementary as possible.<br />

The Darwin Building was limited in height to balance Shaw’s Albert Hall Mansions, which<br />

sits on the opposite side <strong>of</strong> the Albert Hall. The regular but broken skyline <strong>of</strong> the building<br />

was also designed to reflect the gables <strong>of</strong> Shaw’s mansion block, and dark brick cladding was<br />

chosen for the concrete building, so as to mirror the then un-cleaned red brick <strong>of</strong> the Shaw<br />

buildings and the Albert Hall. The entrance and exhibition block opposite the Albert Hall<br />

was kept deliberately low to allow views <strong>of</strong> the hall from the college.<br />

In using staff to plan the building the design shows a good understanding <strong>of</strong> the needs <strong>of</strong> the<br />

college. The interior was intended to be flexible and unobtrusive. Studios open into<br />

workshops and corridors are avoided where possible. The reinforced concrete construction<br />

<strong>of</strong> the main structure allowed the designers to split the building along its axis, giving different<br />

ceiling heights at the front and back. Natural lighting from more than one direction in each<br />

room was also adopted where possible.<br />

The new college proved on the whole to be popular with its students. The RCA boasts an<br />

incredible list <strong>of</strong> alumni, including: Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Sir James Dyson,<br />

David Hockney, Tracey Emin, David Adjaye, and Sir Ridley Scott.<br />

To move to the next location on the <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>Tour</strong> cross back over Kensington Gore and<br />

walk towards the RCA. Take the road to the left between the college and the <strong>Royal</strong> Albert<br />

Hall until you come to number 26, an unusual, highly ornate building on the right hand<br />

side, with the name “<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists” above the black front door.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

11

10. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists<br />

24.15mins<br />

This unusual building was built in 1874-75 to<br />

accommodate the new National Training<br />

School for Music, later to become the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

College <strong>of</strong> Music. Interestingly the architect<br />

was Lieutenant H.H. Cole, the eldest son <strong>of</strong><br />

Henry Cole, one <strong>of</strong> the main figures behind<br />

South Kensington.<br />

Lieutenant Cole, who gave his services for<br />

free on the project, had great experience and<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> Indian archaeology and<br />

architecture. He had also catalogued the casts<br />

for the Indian section <strong>of</strong> the South<br />

Kensington Museum. This interest and<br />

knowledge can be seen in his design, although<br />

his father and members <strong>of</strong> the Science and<br />

Art Department were also consulted.<br />

Cole combined the Old English style <strong>of</strong> the<br />

15 th century, with its large oriel windows,<br />

timber framing and brackets, with Italianate plaster ornament and a polychromatic or multicoloured<br />

façade, resulting in the building having quite a foreign feel.<br />

It was intended that the school contrast with the neighbouring <strong>Royal</strong> Albert Hall, so red<br />

brick and terracotta were avoided. Instead, cream, pale blue and maroon sgraffito, or incised<br />

plaster decoration, was adopted. This decorative scheme was devised by F.W. Moody, who<br />

had also designed for the South Kensington Museum. The frieze features numerous<br />

musicians, reflecting the function <strong>of</strong> the building.<br />

The building and school opened in May 1876, with Sir Arthur Sullivan, <strong>of</strong> Gilbert and<br />

Sullivan fame, as its first principal. In 1883 the School was replaced by the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong><br />

Music, who were already preparing to move to a larger site by 1887. The building stood<br />

vacant from 1896 until 1903 when the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists took a lease for the site for<br />

99 years.<br />

The organists left the building in 1990. Once again the building remained unoccupied for a<br />

while, but it has now been converted and restored for use as a private house.<br />

To reach the next stop on our walk follow the curving road round to the right, walking<br />

down towards Bremner Road. Turn left on to Queen’s Gate and then take the immediate<br />

first left turning into Prince Consort Road. Walk along Prince Consort Road until you come<br />

to a church on the left hand side.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists, c.1876<br />

Reproduced by permission <strong>of</strong> English<br />

Heritage. NMR<br />

12

11. Holy Trinity Church, Prince Consort Road,<br />

26.36mins<br />

Although not part <strong>of</strong> the story <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Albertopolis</strong> it’s worth noting this simple<br />

but beautiful Victorian church. Holy Trinity<br />

Church was one <strong>of</strong> the last works <strong>of</strong> the<br />

architect, G.F. Bodley, built between 1901<br />

and 1906. It is a very fine Gothic Revival<br />

church which looks back to 14 th century hall<br />

churches. It has a simple stone exterior but<br />

with elaborate Perpendicular tracery to the<br />

windows. It was a difficult, confined site to<br />

work with and Bodley succeeded in<br />

producing an elegant church, with a notable<br />

interior complete with most <strong>of</strong> the fittings<br />

being designed by him too. Bodley is<br />

perhaps best known for his designs<br />

produced by the decorating company Watts<br />

& Co. <strong>of</strong> which he was a founder.<br />

Continue now along Prince Consort Road until you come to the entrance to the Imperial<br />

College Union, Beit Quadrangle, on the left hand side. The union courtyard is open to the<br />

public so feel free to wander in.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

12. Imperial College Union<br />

27.39mins<br />

This Students’ Union building was the third<br />

structure which the architect Sir Aston Webb<br />

designed for Imperial College. The college was<br />

founded in 1907 with the joining <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

College <strong>of</strong> Science, the <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines<br />

and the City and Guilds College. By 1910 the<br />

college and its needs had grown considerably<br />

and a Students Union was <strong>of</strong>ficially established<br />

with the commissioning <strong>of</strong> Webb to design a<br />

union building.<br />

The union formed part <strong>of</strong> what became known<br />

as Beit Quadrangle, named after Sir Alfred<br />

Beit, a major benefactor to the college. The<br />

union building today is not recognisable from<br />

Webb’s original design. In the 1920s student<br />

accommodation was built in front <strong>of</strong> and<br />

Holy Trinity Church, 2010<br />

Photographer: Wilson Yau<br />

Design for hostel for 50 students<br />

(part <strong>of</strong> the Beit Quadrangle), 1924<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Drawings<br />

and Archives Collections<br />

13

around the union, again to a design by Webb, however these have since been considerably<br />

added to, including an additional storey on top.<br />

Continue along Prince Consort Road, pausing at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the steps which lead up to<br />

the Albert Hall. In the centre <strong>of</strong> the steps you’ll see the Memorial to the Great Exhibition<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1851, designed by Joseph Durham, and appropriately topped with a statue <strong>of</strong> Prince<br />

Albert. Now turn around to face the grand red brick building on the other side <strong>of</strong> the road,<br />

the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

13. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music<br />

28.57mins<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music began its days in<br />

1873 as the National Training School for Music.<br />

Initially it was housed in the building known as<br />

the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Organists, which we have<br />

already visited on this walk.<br />

By 1887 the school had changed its name to the<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music and it had outgrown its<br />

premises. The 1851 Commissioners <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

them a new site, first <strong>of</strong> all on the west side <strong>of</strong><br />

Exhibition Road, and later a second site, the one<br />

before you.<br />

This new location was on the south side <strong>of</strong> a<br />

new street, Prince Consort Road, and was<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered with a lease for 999 years. The college<br />

commissioned the experienced architect Sir<br />

Arthur Blomfield to design their new premises,<br />

and he produced a grand, red brick French<br />

baronial style building which was formally<br />

opened by the Prince <strong>of</strong> Wales on 2 May 1894.<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Music, 2010<br />

Photographer: Wilson Yau<br />

Blomfield had faced quite a challenge. The site<br />

was north facing, overlooked by the majestic Albert Hall, and at the time two large blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

flats were planned to be built either side. The architect therefore needed to produce<br />

something tall and grand, to compete with its neighbours.<br />

He insisted his design for the main façade must wait until the plan had been completely<br />

decided upon. However, in the end he had to provide a façade for a tall building consisting<br />

mainly <strong>of</strong> small rooms in storeys <strong>of</strong> nearly equal and modest height. The result was a façade<br />

with small-scale subdivisions, and as such it was criticised for its lack <strong>of</strong> monumentality and<br />

interest.<br />

Blomfield faced further disappointment in that he had intended to further develop the<br />

building behind with two quadrangles, but this was put <strong>of</strong>f until later, and ultimately was not<br />

built by Blomfield. The college underwent several extensions in the 1960s, including one to<br />

14

the south side <strong>of</strong> Blomfield’s building, and this was designed by the architects <strong>of</strong> the new<br />

Imperial College, Norman and Dawbarn.<br />

Continue walking westwards along Prince Consort Road, towards Exhibition Road, until you<br />

come to the next building, the <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines, now part <strong>of</strong> the Imperial College <strong>of</strong><br />

Science and Technology.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

14. <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines<br />

31.08mins<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines began<br />

life in 1851 with the Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Practical Geology. It was the first<br />

government backed technical higher<br />

education establishment in the<br />

United Kingdom. Initially it sat in<br />

Jermyn Street, central London,<br />

however after a number <strong>of</strong><br />

developments, including a merger<br />

with the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Chemistry<br />

in 1853, the school outgrew its<br />

accommodation and in the 1870s the<br />

school moved piecemeal to South<br />

Kensington. At first it moved in to<br />

the building that is now the Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> the V&A, but then into a purpose-built<br />

structure by Sir Aston Webb, which is the building before you.<br />

Built between 1910 and 1913 Webb designed the <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines as an imposing<br />

classical structure. The entrance to the school uses the Ionic order and is recessed into the<br />

building. It is dominated by the two flanking statues outside, those <strong>of</strong> Sir Julius Charles<br />

Werhner and Sir Alfred Beit, both substantial benefactors to the School who died just before<br />

the building was completed.<br />

During construction the <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines joined with the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science and<br />

the City and Guilds College to form Imperial College. It is the only building <strong>of</strong> these three to<br />

have survived the 1950s and 60s reconstruction <strong>of</strong> Imperial College.<br />

Turn right into Exhibition Road, walk past the modern entrance to Imperial College and<br />

then turn right into Imperial College Road. Walk about 50 metres along the road until you<br />

notice a stripy brick building on the left hand side with obelisk street lamps in front.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines, 1910<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Drawings and Archives<br />

Collections<br />

15

15. <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science<br />

32.41mins<br />

Imperial College Road today<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> a mish-mash <strong>of</strong> buildings<br />

from different ages. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

oldest is the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong><br />

Science, a very small section <strong>of</strong><br />

which survives, sandwiched between<br />

the Post Office building and the Sir<br />

Alexander Fleming Building <strong>of</strong><br />

Imperial College, all <strong>of</strong> which sit on<br />

the south or left-hand side <strong>of</strong> the<br />

road.<br />

The college was designed by Sir<br />

Aston Webb at the turn <strong>of</strong> the 20th<br />

century. The remnant <strong>of</strong> this<br />

formerly imposing building is<br />

recognisable by its bold stripy brick<br />

courses and round-arched windows.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> Webb’s original obelisk street lamps which ran along the building’s frontage also<br />

survive.<br />

This building was not the original location <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science. The college was<br />

first founded in 1881 as the Normal School <strong>of</strong> Science and it shared a home with the School<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mines in the building that is now known as the Henry Cole Wing <strong>of</strong> the V&A. The college<br />

later gained the <strong>Royal</strong> title, and over the next twenty years both Schools grew considerably,<br />

outgrowing their premises.<br />

Aston Webb was employed to design new homes for both colleges and he began with the<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science. In 1898 the 1851 Commission <strong>of</strong>fered land opposite the Imperial<br />

<strong>Institute</strong>, valued at £100,000, if government funding was made available for construction <strong>of</strong><br />

the building. It was, and between 1900 and 1906 Webb built a large classical structure,<br />

complete with new modern well equipped laboratories.<br />

The <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science was undertaken at the pinnacle <strong>of</strong> Webb’s career. Around this<br />

time he was also working on the main front <strong>of</strong> the V&A, the <strong>Royal</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Mines, and<br />

Admiralty Arch on Trafalgar Square. Between 1902 and 1904 Webb was President <strong>of</strong> the<br />

RIBA, and in 1904 he received a knighthood.<br />

Sadly the college was almost entirely demolished in the early 1960s and 1970s, as part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

major reconstruction <strong>of</strong> Imperial College.<br />

Continue walking eastwards along Imperial College Road until you’re standing in front <strong>of</strong> a<br />

lone tall tower, topped by a green copper dome, the Queen’s Tower <strong>of</strong> Imperial <strong>Institute</strong>.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

Exterior <strong>of</strong> <strong>Royal</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Science, c. 1900<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Photographs Collection<br />

16

16. Queen’s Tower, Imperial <strong>Institute</strong><br />

34.57mins<br />

Before you is the sole survivor <strong>of</strong> T.E.<br />

Collcutt’s Imperial <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1893,<br />

the Portland stone Queen’s Tower. It<br />

stands proudly reaching a height <strong>of</strong> 285<br />

feet, looking down today on Imperial<br />

College and dominating the<br />

Kensington skyline with its colourful<br />

green copper dome.<br />

This plot and the surrounding lands<br />

used to be the site <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong><br />

Horticultural Society Gardens until<br />

they were closed in 1882. The first <strong>of</strong><br />

the new buildings on the land was the<br />

Imperial <strong>Institute</strong>, founded after the<br />

Imperial Exhibition <strong>of</strong> 1886 and in<br />

celebration <strong>of</strong> the Queen’s Golden<br />

Jubilee. Its purpose was to encourage<br />

scientific study relevant to all countries<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>British</strong> Empire, through<br />

research, exhibitions, and conferences.<br />

It was intended to encourage<br />

emigration, expand trade, and to<br />

promote the commercial and industrial<br />

prosperity <strong>of</strong> the empire. The location<br />

in South Kensington had been received<br />

with some criticism – many preferred<br />

Westminster as a more apt location,<br />

however finances dictated a less central<br />

location.<br />

Contract design for the Principal Tower <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Imperial <strong>Institute</strong>, 1888<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Drawings and Archives<br />

Collections<br />

Thomas Edward Collcutt won the competition to design the institute and he created a Neo-<br />

Renaissance style building. His design consisted <strong>of</strong> a simple symmetrical plan, a strong<br />

building pr<strong>of</strong>ile with a 700 foot long front with a large central tower (the Queen’s Tower),<br />

and smaller towers at the ends. The façade used what became a Collcutt trademark,<br />

horizontal stripes <strong>of</strong> brick through stone, a feature you might be more familiar with at the<br />

Palace Theatre in London’s West End, which was also designed by Collcutt. It could also be<br />

that Aston Webb had Collcutt’s use <strong>of</strong> stripes in mind when he designed the <strong>Royal</strong> College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Science, which is on the other side <strong>of</strong> the street.<br />

Although Collcutt’s Imperial <strong>Institute</strong> design was in the French Early Renaissance style the<br />

building was intended as a symbol <strong>of</strong> the <strong>British</strong> Empire. As such the smaller turrets that<br />

used to flank the tower were capped by onion domes, possibly in tribute to India. Above the<br />

entrance door Collcutt also placed the patriotic inscription: “Strength and honour are her<br />

clothing.”<br />

The institute did not prove to be a success and already in 1899 the University <strong>of</strong> London<br />

took over half <strong>of</strong> the building as administration <strong>of</strong>fices. By 1936 the university moved out to<br />

Bloomsbury and for the next 20 years the institute was subject to various changes <strong>of</strong><br />

administration.<br />

17

In 1953 the government announced a scheme for the expansion <strong>of</strong> Imperial College, which it<br />

became apparent would include the demolition <strong>of</strong> Collcutt’s building. Imperial College had<br />

been created in 1907 with the merger <strong>of</strong> several technical colleges which had been set up on<br />

and around the site in South Kensington<br />

Fondness for the tower was such that when it was proposed to demolish Imperial <strong>Institute</strong> in<br />

the 1950s, the tower alone was saved. After the demolition <strong>of</strong> the surrounding, supporting<br />

buildings, the tower had to be reinforced with a new base and foundations. Interestingly this<br />

exercise was carried out in part by the same people who straightened the leaning tower <strong>of</strong><br />

Pisa.<br />

The tower used to be open to visitors, to admire the view from the top gallery, where in<br />

good conditions you can see for 20 miles. Unfortunately it is now closed due to lack <strong>of</strong><br />

resources, and also reputedly due to the number <strong>of</strong> student suicides which took place here.<br />

The tower also contains an important collection <strong>of</strong> bells, the Alexandra Peal <strong>of</strong> bells, which<br />

can be heard on royal anniversaries and on Imperial College graduation days. The peal in the<br />

belfry consists <strong>of</strong> 10 bells, all named after members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Royal</strong> family. Also worth noting<br />

are the two majestic stone lions which sit beneath the tower to the north side. Originally<br />

there were four lions flanking the entrance to Imperial <strong>Institute</strong>, the other two were removed<br />

during demolition <strong>of</strong> the institute and taken to its successor, the Commonwealth <strong>Institute</strong>.<br />

Continue walking westwards along Imperial College Road. Continue through the gates at<br />

the end and pause to look at the house at the very end <strong>of</strong> the street on the right hand site,<br />

no. 170 Queen’s Gate.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

17. 170 Queen’s Gate<br />

39.06mins<br />

170 Queen’s Gate is one <strong>of</strong> a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> houses the architect Richard<br />

Norman Shaw designed along this<br />

prestigious London street. Today it is<br />

the rector’s house for Imperial College.<br />

It also serves as a meeting venue and is<br />

available for private hire.<br />

The house, which was completed in<br />

1889, was commissioned by Frederick<br />

Anthony White, a wealthy cement<br />

manufacturer with an interest in art and<br />

architecture. The White family crest sits<br />

proudly above the front door, and the<br />

initials <strong>of</strong> White and his wife can be<br />

seen on the rainwater heads.<br />

170 Queen’s Gate, 1900<br />

Copyright: RIBA Library Photographs Collection<br />

The red brick house with its stone<br />

dressings is an important example <strong>of</strong> English domestic architecture <strong>of</strong> the period. It follows<br />

very loosely the style which Shaw became internationally famous for, the Queen Anne style.<br />

18

However, it doesn’t have the very distinctive Queen Anne motifs which Shaw employed<br />

nearby at Lowther Lodge.<br />

170 Queen’s Gate changed hands a number <strong>of</strong> times before it was acquired by Imperial<br />

College in 1947. It was then altered slightly by Sir Hubert Worthington, consultant architect<br />

to the college, to adapt it to the College’s needs.<br />

Its future was threatened in the 1950s and 1960s when Imperial College was looking to<br />

radically expand and rebuild. Another nearby Shaw house, 180 Queen’s Gate was demolished<br />

to make way for new buildings, as was the nearby Imperial <strong>Institute</strong>. However fortunately<br />

Shaw’s houses at 170 and 196 Queen’s Gate were saved and today number 170 remains a key<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the college’s estate.<br />

Now turn left to walk southwards down Queen’s Gate, past the Dana Centre, until you<br />

come to a large modern building set back from the street on the left hand side which is the<br />

Darwin Centre <strong>of</strong> the Natural History Museum. Move slightly down along the road so that<br />

you have a good view <strong>of</strong> the striking glass wall which faces the building to the south,<br />

perpendicular to Queen’s Gate.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

Darwin Centre, Natural History Museum<br />

41.05mins<br />

The most recent phase in the development <strong>of</strong> the Natural History Museum is the Darwin<br />

Centre. This extension to the Museum acts not only as a store for some <strong>of</strong> its vast collections<br />

but also provides new laboratories for the scientists working at the museum, and “behind the<br />

scenes” access for visitors.<br />

The centre was planned in two parts: Phase I being completed in 2002 by the architectural<br />

firm HOK, and Phase II, designed by CF Møller, opened in 2009.<br />

18. Darwin Centre, Natural History Museum, Phase I<br />

41.40mins<br />

Phase I <strong>of</strong> the Darwin Centre is that immediately before you and contains storage for the<br />

Museum’s collection <strong>of</strong> 22 million zoological specimens stored in spirit, and is an excellent<br />

example <strong>of</strong> a new wave <strong>of</strong> environmental architecture.<br />

The building is faced by a large glass solar wall, designed to reduce heat in summer and heat<br />

loss in winter. It has a “caterpillar” ro<strong>of</strong> made <strong>of</strong> recyclable materials, which lets in lots <strong>of</strong><br />

natural light, reducing the need for electricity.<br />

The choice <strong>of</strong> these environmental features also follows the designer’s wish to reflect on the<br />

outside <strong>of</strong> the building what happens inside, just as Alfred Waterhouse did with his animal<br />

sculptures on the main building <strong>of</strong> the Natural History Museum.<br />

19

HOK achieve this by using zoomorphic<br />

brackets in the solar wall; sun-tracking metal<br />

louvers which move, changing the appearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> the building; and a triple-skin caterpillar like<br />

inflated ro<strong>of</strong>; all <strong>of</strong> which act to reflect the<br />

centre’s work and ideals.<br />

The designers also wanted to provide a visual<br />

connection to the main museum building by<br />

Waterhouse. It therefore incorporates<br />

terracotta, and the steel frame echoes the blue<br />

terracotta <strong>of</strong> the Victorian building.<br />

HOK is a global firm <strong>of</strong> architects well known<br />

for completing large scale projects. Most<br />

notably the Heathrow Terminal 5 Rail Station,<br />

and the National Air and Space Museum in<br />

Washington DC.<br />

Move slightly further down along Queen’s Gate to get a good view <strong>of</strong> the large, long glass<br />

building which sits immediately alongside Phase I.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

19. Darwin Centre, Natural History Museum, Phase II<br />

43.14mins<br />

Phase II <strong>of</strong> the Darwin<br />

Centre is a state <strong>of</strong> the art<br />

scientific research and<br />

collections facility housed<br />

within a 16,000 square metre<br />

building. It securely stores the<br />

museum’s entomology and<br />

botany specimens: some 17<br />

million insects and 3 million<br />

plants.<br />

Exterior <strong>of</strong> the Darwin Centre, Phase I, 2002<br />

Copyright: The Natural History Museum,<br />

London<br />

The key concept for the Long section <strong>of</strong> the Second Phase <strong>of</strong> the Darwin Centre, 2001<br />

building by C.F. Møller Reproduced by kind permission <strong>of</strong> C. F. Møller Architects<br />

Architects is a giant cocoon<br />

encased within a glass box, a<br />

fitting concept for a building dedicated to studying plants and insects. The 60 metre long<br />

building contains eight storeys which meet around a central atrium.<br />

C.F. Møller Architects is one <strong>of</strong> Scandinavia’s oldest and largest architectural practices.<br />

Founded in 1924 by the late Christian Frederik Møller, a Danish architect and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor, the<br />

firm is mainly known for its works in Denmark.<br />

20

Continue to walk down Queen’s Gate until you meet the junction with Cromwell Road,<br />

then turn left, walking along the main front <strong>of</strong> the Natural History Museum, until you come<br />

the museum gates.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

20. Natural History Museum<br />

44.19mins<br />

The iconic Natural History Museum<br />

opened in April 1881 to much praise,<br />

including a description in The Times as<br />

‘a true Temple <strong>of</strong> Nature.’ It also caught<br />

the headlines as the first building in<br />

Britain to be faced entirely in terracotta.<br />

Its story begins in the 1850s when the<br />

<strong>British</strong> Museum recognised that its<br />

Natural History Collections had<br />

outgrown their Bloomsbury site. After<br />

much debate it was decided in 1860 to<br />

build them a new home in South<br />

Kensington. Initially the designer was to<br />

be the engineer Francis Fowke, who had<br />

designed much <strong>of</strong> the South Kensington<br />

Museum. However, Fowke died<br />

Natural History Museum, 1876<br />

Copyright: V&A images<br />

suddenly in 1865, and he was replaced by a rising star from Manchester, Alfred Waterhouse.<br />

At first Waterhouse simply revised Fowke’s design, but with a change in government in 1866<br />

he was given greater licence to make changes, and effectively designed a new building.<br />

Waterhouse bucked the current architectural fashion <strong>of</strong> adopting the Gothic style, and<br />

instead opted for his own version <strong>of</strong> German Romanesque. He explained his choice due to it<br />

suiting a museum, giving it order, grandeur and simplicity, appropriate qualities for a natural<br />

history collection.<br />

Key features <strong>of</strong> Waterhouse’s Romanesque design include:<br />

• Round-arched windows and entrance.<br />

• A double entrance portal.<br />

• Central twin towers, inspired by several German churches, including the Minster <strong>of</strong><br />

St. Martin in Bonn which Waterhouse visited and sketched in 1857. It’s worth noting<br />

that the large scale <strong>of</strong> the towers is also due to demands from the London Fire<br />

Office, who stipulated that the towers should contain water tanks large enough to<br />

provide sufficient pressure to tackle any fires.<br />

• And finally, another Romanesque quality Waterhouse adopted was naturalistic<br />

decoration using plant and animal motifs.<br />

The façade is decorated according to the wishes <strong>of</strong> the museum’s first director, Sir Richard<br />

Owen. Owen wanted the purpose <strong>of</strong> the museum conveyed on the exterior: the west side is<br />

decorated with living species; and the east side with extinct species. Owen and Waterhouse<br />

21

were possibly influenced in their choice <strong>of</strong> decoration by the University Museum, Oxford, by<br />

Deane & Woodward, which Waterhouse visited in 1858.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> the decoration and the whole façade facing are carried out in terracotta. Waterhouse<br />

chose this relatively new material since it could mass produce cheap, durable, and washable<br />

ornament.<br />

The overall result <strong>of</strong> the façade is reminiscent <strong>of</strong> both a cathedral front and a medieval<br />

market hall. The building is entered via a magisterial staircase and cathedral like portal, a<br />

theme which is continued in the grand entrance hall which resembles a large church nave.<br />

The interior <strong>of</strong> the museum is equally as decorative and beautiful as its exterior and is well<br />

worth exploring, even if you’re not interested in dinosaurs!<br />

Continue to walk eastwards along Cromwell Road towards the main entrance to the V&A.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

21. Victoria and Albert Museum<br />

47.22mins<br />

Before you is the world renowned<br />

Victoria and Albert Museum, however<br />

the museum began its life under a<br />

different name and in a different<br />

location. The first seed <strong>of</strong> what was to<br />

become the South Kensington<br />

Museum, and later the V&A, was the<br />

founding <strong>of</strong> the Government School <strong>of</strong><br />

Design, established in Somerset House<br />

in 1837. The Department <strong>of</strong> Practical<br />

Art followed in 1852 with the<br />

associated Museum <strong>of</strong> Manufactures set<br />

up in Marlborough House, which<br />

included objects purchased from the<br />

Great Exhibition.<br />

Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> the Victoria and Albert<br />

Museum, 2002<br />

Copyright: English Heritage. NMR<br />

The result was the first public<br />

institution to <strong>of</strong>fer education in design,<br />

with the objective to make works <strong>of</strong> art<br />

available to all, and to inspire contemporary design. Both the department and museum were<br />

renamed in 1853, and in 1857 they moved to the site before you.<br />

Henry Cole became the museum’s first director, and it was he who coined the name South<br />

Kensington for both the area and the museum. The South Kensington Museum opened in<br />

the summer <strong>of</strong> 1857 to the north east <strong>of</strong> where you are standing, in a temporary iron building<br />

which earned the derogatory nickname the ‘Brompton Boilers.’ Cole quickly employed the<br />

engineer Captain Francis Fowke to design new permanent buildings for the museum<br />

collections. The Brompton Boilers was dismantled in 1864 and partially re-erected at Bethnal<br />

Green for a new museum, now the Museum <strong>of</strong> Childhood.<br />

22

Fowke remained the architect for the South Kensington Museum until his death in 1865,<br />

when his work was taken over by another engineer, Major Henry Scott, also architect for the<br />

Albert Hall. The last building to be erected following Fowke and Scott’s plans for the<br />

museum was the National Art Library, opening in 1884. No further building work was<br />

proposed until a competition was launched in 1891 to complete the Museum towards the<br />

Cromwell Road. Up until then the museum lay further to the north than where are standing.<br />

The winner <strong>of</strong> the 1891 competition was the architect Aston Webb, and it’s this building and<br />

entrance front that you see before you on the Cromwell Road. Queen Victoria laid the<br />

foundation stone for the building in 1899 and at this ceremony that she renamed the<br />

institution the Victoria and Albert Museum.<br />

Now enter the V&A by the main entrance and head for the museum restaurant. To reach<br />

your well earned cup <strong>of</strong> tea, and the last location for the <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>Tour</strong>, walk straight through<br />

the museum, passing directly through the museum entrance, shop and Madejski Gardens, to<br />

enter the museum’s Refreshment Rooms, the world’s first museum public restaurant, located<br />

in the north wing <strong>of</strong> the Museum Quadrangle.<br />

Pause the recording<br />

22. Refreshment Rooms, V&A<br />

50.10mins<br />

To reach this part <strong>of</strong> the V&A<br />

you have passed through some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the oldest parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

institution, including the<br />

Museum Quadrangle, now the<br />

Madejski Gardens, which<br />

encompasses to east or right<br />

hand side, the former<br />

Sheepshanks Gallery, the oldest<br />

surviving original gallery <strong>of</strong> the<br />

South Kensington Museum; and<br />

to the north, the Lecture Theatre<br />

Block by Francis Fowke.<br />

On the ground floor <strong>of</strong> the Lecture<br />

Theatre Block are the museum’s<br />

Refreshment Rooms, the oldest<br />

museum public restaurant in the<br />

Gamble Room <strong>of</strong> the V&A Refreshments Rooms, 2006<br />

Copyright: V&A Images<br />

world, opening in 1857. It consists <strong>of</strong> a suite <strong>of</strong> three rooms, the central one <strong>of</strong> which is the<br />

Gamble Room.<br />

This incredibly grand and opulent space has a semi-circular northern side, following the plan<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Lecture Theatre which sits directly above it. At the back <strong>of</strong> this are stained glass<br />

windows intended to hide the kitchens behind.<br />

23

The room itself was designed by James Gamble with Godfrey Sykes and Reuben Townroe.<br />

The entire room is washable, with an enamelled iron ceiling and every surface covered in<br />

ceramic tiles. Even the four large free-standing columns in the room are faced in majolica<br />

tiles. The overall result is a glossy, highly coloured, opulent room.<br />

Either side <strong>of</strong> the Gamble Room are the two smaller, less grandiose, but nevertheless<br />

beautiful rooms. To the west is the Green Dining or Morris Room since it was one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

first big jobs <strong>of</strong> the firm Morris Marshall & Faulkner. Philip Webb was responsible for the<br />

overall design, and Burne-Jones painted the dado panels and designed the stained glass.<br />

The room at the east end is the Grill Room designed by Edward Poynter. A more intimate<br />

room with blue Dutch tiles set in wooden panelling, and larger tiled panels <strong>of</strong> figures<br />

representing the seasons designed by art school students.<br />

Congratulations on reaching the final stop on our tour <strong>of</strong> <strong>Albertopolis</strong>! I hope that you’ve<br />

enjoyed the walk and that perhaps you can now treat yourself to a well-earned refreshment in<br />

this historical venue.<br />

www.architecture.com<br />

24