Ouachita Map Turtle Graptemys ouachitensis ... - Ohio University

Ouachita Map Turtle Graptemys ouachitensis ... - Ohio University

Ouachita Map Turtle Graptemys ouachitensis ... - Ohio University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Ouachita</strong> <strong>Map</strong> <strong>Turtle</strong><br />

<strong>Graptemys</strong> <strong>ouachitensis</strong> <strong>ouachitensis</strong> (Cagle 1953)<br />

Kathleen G. Temple-Miller, Willem M. Roosenburg, Matthew M. White<br />

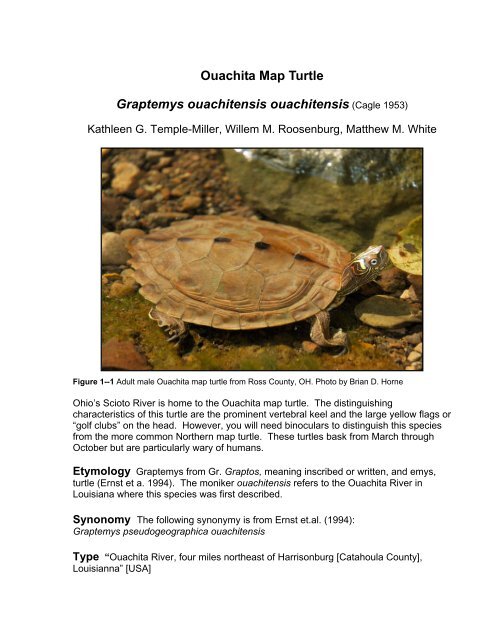

Figure 1--1 Adult male <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle from Ross County, OH. Photo by Brian D. Horne<br />

<strong>Ohio</strong>’s Scioto River is home to the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle. The distinguishing<br />

characteristics of this turtle are the prominent vertebral keel and the large yellow flags or<br />

“golf clubs” on the head. However, you will need binoculars to distinguish this species<br />

from the more common Northern map turtle. These turtles bask from March through<br />

October but are particularly wary of humans.<br />

Etymology <strong>Graptemys</strong> from Gr. Graptos, meaning inscribed or written, and emys,<br />

turtle (Ernst et a. 1994). The moniker <strong>ouachitensis</strong> refers to the <strong>Ouachita</strong> River in<br />

Louisiana where this species was first described.<br />

Synonomy The following synonymy is from Ernst et.al. (1994):<br />

<strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica <strong>ouachitensis</strong><br />

Type “<strong>Ouachita</strong> River, four miles northeast of Harrisonburg [Catahoula County],<br />

Louisianna” [USA]

Taxonomic Status <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles were a subspecies of G.<br />

pseudogeographica, the False <strong>Map</strong> turtle, (Cagle 1953) and supported by Ward (1980).<br />

The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle was given taxonomic distinction from G. pseudogeographica<br />

due to morphological differences in head markings and absence of hybridization<br />

between G. pseudogeographica and G. <strong>ouachitensis</strong> in areas of sympatry (Vogt 1978;<br />

1980; 1993). Recent molecular data supports species status because G. <strong>ouachitensis</strong><br />

does not group with G. pseudogeographica in molecular data sets (Stephens and Wiens<br />

2003)<br />

Common Names <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle<br />

Description<br />

The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle is an average to large map turtle. The dark brown<br />

carapace of the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle has black splotches usually along the keel of the<br />

carapace and includes serrated marginals. The vertebral keel has low spines and is<br />

especially prominent in smaller individuals. The plastron surface is light yellow or cream<br />

with black curving and reticulated lines. The ventral sides of the marginals are similar<br />

with light yellow or cream coloration and black curving lines similar to a topographic<br />

map. The yellow head stripes are common to all map turtles but one to nine head<br />

stripes and the broad yellow flag extending over the head identifies the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map<br />

turtle (Ernst et al., 1994) . The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle can be distinguished from the false<br />

map turtle by the presence of 2 large spots below the eye (figure 1--2). The post-orbital<br />

flag or stripe may vary in size and shape from oval to rectangular or square and usually<br />

extends down to the orbit. There are small light spots on each side of the face below<br />

the orbit in addition to one on the lower jaw but these are difficult to discern and may be<br />

absent in some individuals. In older individuals, the yellow flags and stripes can fade<br />

and can be difficult to distinguish unless the turtle is in hand. The skin is dark brown with<br />

lighter brown stripes gradually changing to yellow at the distal range of all appendages:<br />

tail, legs, neck, and chin. All limbs lack scales and the hind limbs have webbing<br />

between the digits. The Scioto River population has white eyes although populations<br />

outside of <strong>Ohio</strong> may have a yellow or golden eye color.<br />

Figure 1--2. Note<br />

the broad post<br />

orbital stripe, white<br />

eyes, and one to<br />

nine head stripes<br />

characteristic of<br />

the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map<br />

turtle found in the<br />

Scioto River, OH.

<strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles are sexually dimorphic. Adult females’ plastron lengths<br />

range from 89--185 mm while adult males range from 77--99 mm (Lindeman 1999).<br />

Males often have long nails on their front forelimbs, long broad tales, and a cloacal<br />

opening beyond the posterior carapace margin. Females are much larger and weigh<br />

370--1600g while the largest male captured in <strong>Ohio</strong> was only 329g (Temple-Miller<br />

2008).<br />

Table 1—1 Population means and ranges for the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle from the Scioto River (Temple-<br />

Miller 2008).<br />

Sex (n) Carapace<br />

(mm)<br />

Plastron (mm) Mass (g)<br />

J (5) 95 (69—120) 85(61—106) 122(44—209)<br />

M (38) 119(103—142) 105(86—123) 201(131—329)<br />

F (35) 204(122-230) 176(92—214) 1168(74—1614)<br />

<strong>Ohio</strong> has two map turtle species. The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle has the large post-orbital<br />

stripes, flags, extending above the head and often a white spot on the lower jaw and<br />

below the orbit. Adult female Northern map turtles have a prominent jaw while <strong>Ouachita</strong><br />

<strong>Map</strong> turtles have a more distinctive keel and small spines. Northern map turtle adult<br />

female’s head can be considerably wider than a comparably sized <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle.<br />

The eye color is also different with white or cream eyes in <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles (in the<br />

Scioto River) while Northern map turtles have yellow or golden eyes.<br />

Distribution<br />

<strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles occur throughout the Mississippi River basin but the distribution<br />

suggests that the population in <strong>Ohio</strong>’s Scioto River is disjunct (Ernst et al. 1994; Figure<br />

1-3). Smith (2008) suggested that the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle likely had several dispersal<br />

events and that a population extended throughout the <strong>Ohio</strong> River valley at one time.<br />

The Scioto River is the only currently recorded <strong>Ohio</strong> <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle population and<br />

was first described by Conant et al. (1964). The earliest record of the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map<br />

turtle in <strong>Ohio</strong> is a museum specimen National Museum of Natural History deposited<br />

there by L. Lesquereux that was collected near Columbus in 1872 (Conant et al. 1964).<br />

This early specimens strongly suggests that the <strong>Ohio</strong> population is a natural occurance<br />

Conant et al. (1964). Today map turtles in the Scioto River extend from Circleville to<br />

Portsmouth, <strong>Ohio</strong>, but most individuals are found in clusters near Kingston, Waverly,<br />

and Lucasville, <strong>Ohio</strong>. Individuals in the Scioto River north of Circleville are rare but<br />

populations seem stable in Ross, Pike, and Scioto counties (Temple-Miller 2008).<br />

Turkeyfoot Lake, Scioto County, in close proximity to the Scioto River, contains at least<br />

one individual although in-depth surveys outside of the lower portion of the Scioto River<br />

are lacking. Prior to 1973 <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles (historically the False map turtle) were<br />

spotted on the West Virginia shores of the <strong>Ohio</strong> River across from Washington County,<br />

<strong>Ohio</strong> (Smith et al. 1973). However, it is unknown whether this species is the False map<br />

turtle or the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle since no recent studies have reported this species in<br />

this area.

Figure 1—3 <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle national distribution map (Ernst et al. 1994).<br />

Figure 1--4 <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle distribution on the Scioto River (Temple-Miller 2008).<br />

Natural History<br />

Emydid turtles associate with deadwood along river banks indicating the<br />

importance of natural riparian areas that provide basking habitat (Shively and Jackson<br />

1985; Pluto and Bellis 1986; Fuselier and Edds 1994; Lindeman 1999). Most map<br />

turtles prefer basking locations found in deep water, offshore, and exposed to the sun.<br />

<strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles prefer fast flowing rivers (Vogt 1980, Black et al. 1987, Harvey<br />

1992) but may also inhabit oxbows, ponds, and lakes. The most preferential substrates<br />

are sand and silt over gravel and mud (Ewert 1979). Most importantly, sand and gravel<br />

bars formed by natural channel movement serve as vital nesting ground for <strong>Graptemys</strong>.

Wider river habitats are also preferred (Fuselier and Edds 1994), and turtles often<br />

associate with the presence of filamentous algae and available basking sites (Shively<br />

and Jackson 1985). Spring surveys in the Scioto River show G. <strong>ouachitensis</strong> closer to<br />

shallow bars and in wider stretches of the river than the sympatric G. geographica.<br />

Throughout the active season, females in the Scioto River preferred deeper water and<br />

finer substrate, which are often characteristic of their habitat near root wads and large<br />

woody debris (Figure 1-- 5) (Temple-Miller 2008).<br />

<strong>Map</strong> turtle habitat is complex requiring many different resources. Basking for all<br />

aquatic emydid turtles is a thermoregulatory behavior, although basking may also<br />

desiccate leeches and other skin parasites, epizootic algae, and aide in vitamin-D<br />

synthesis (Boyer 1965). Interestingly grackles feed on leeches while map turtles are<br />

basking providing an important symbiotic relationship (Vogt 1979). The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map<br />

turtle spends most of the day basking during the active season and can be found in high<br />

densities in the spring and fall perhaps in association with their hibernacula or<br />

reproductive cycles. Although there is no evidence of aggressive behavior between<br />

map turtles for basking sites, larger individuals ultimately have the ability to displace<br />

smaller turtles while basking and causes them to drop into the water (Lindeman 1999).<br />

Previously observed movements include the pursuit of seasonally available food<br />

sources, migration to hibernacula, juvenile migration from nest sites, and discarding<br />

unsuitable habitats (Ernst et al. 1994). River turtles use habitat differentially based on<br />

size and sex. Since smaller size equates with a lack in swimming ability in strong<br />

currents, smaller turtles usually occupy slower moving water such as back channels,<br />

protected areas, and tributaries (Moll and Moll 2004); while larger female map turtles<br />

move throughout expansive areas within the Mississippi River (Vogt 1980). In<br />

Pennsylvania, common hibernacula are deep riverine pools (Pluto and Bellis 1988) yet<br />

in Kentucky impoundments are common (Ernst et al 1994). Adult female map turtles<br />

migrate to suitable nesting locations (Gibbons and Lovich 1990) and seek adult males<br />

for mating (Tuberville et al. 1996). The nesting period varies regionally but typically<br />

begins in late May and ends by mid-July (Ernst et al. 1994).<br />

The male courtship behavior includes drumming of the foreclaws against the<br />

female’s ocular region. Typically males will make contact with the ocular region 5.2<br />

times per vibration attempt (Ernst et al. 1994). Mating in <strong>Ohio</strong> likely takes place in April,<br />

October, and November similar to a Wisconsin population (Vogt 1980). Males mature<br />

at 6 cm plastron length in Louisiana (Cagle 1953) but in Oklahoma they are mature at 7<br />

cm plastron length (Webb 1961). <strong>Ohio</strong>’s maturity rates are likely similar to Wisconsin<br />

because they have similar active periods. Females lay their first clutch in Wisconsin<br />

between the middle of May and mid-June (Vogt 1980). Most nesting occurs in the<br />

morning between 6:30 and 10:00 and females will lay two and sometimes three clutches<br />

per year. Most clutches contain between 6 and 15 eggs with a mean of 10.5 eggs per<br />

clutch (Vogt 1980). Hatchlings rarely overwinter in the nest and only weigh 1.5-6.2g.<br />

The carapace is only 27.1-35mm long while the plastron is only 22.2-34 mm long.<br />

(Cagle 1953, Webb 1961, Vogt 1980).<br />

<strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles have type I environmental sex determination (ESD); Eggs<br />

incubated at a constant 28°C develop into males while eggs incubated at a constant<br />

30°C produce nearly all females (Bull et al. 1982, Ewert and Nelson 1991). The most<br />

influential temperature occurs in the middle third of development (Bull and Vogt 1981).<br />

Ultimately temperature can skew population sex ratios. The Oauchita <strong>Map</strong> turtle<br />

typically has a hatchling sex ratio of 1.9:1 (female to male) in Minnesota (Charnov and

Bull, 1989). <strong>Ohio</strong>’s adult Scioto River population is consistent, with a sex ratio of 1.7:1<br />

(Temple-Miller 2008). <strong>Map</strong> turtles sex ratio in Wisconsin (Vogt 1980) and South Dakota<br />

(Timken 1968) consistently were 4:1 female biased<br />

The <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle feeds on the bottom as well as at the surface by<br />

extending the neck and exposing about 1/3 of the shell (Vogt 1981a). Digestive tracts<br />

of <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles revealed mostly vegetation and a few insects, yet the turtles<br />

had an attraction to fish, mussels, and crayfish during trapping (Moll1976). This<br />

behavior is typical of an opportunistic feeder in congruence with smaller turtles<br />

containing more insects and larger turtles eating more plant material (Moll 1976).<br />

Dense algae on logs are also a primary food source particularly as turtles become<br />

larger (Shively and Jackson 1985, Moll 1976). In Wisconsin, <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles ate<br />

by volume: mollusks 2.8%, plant material 31.5%, insects 51%, and 15% unknown (Vogt<br />

1981a). Common habitats for <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles contain areas of eddy-drop zones<br />

for opportunistic foraging (Figure 1—4). As the current strikes the root wad debris and<br />

organisms drop out of the current in the course of eddies.<br />

Figure 1-4 Representative <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle habitats in the Scioto River. Both pictures contain eddydrop<br />

zones, which cause invertebrates and other aquatic organisms to drop out of suspension.<br />

Predators: Fly maggots (Metoppsarcophaga importans) may consume eggs in<br />

Wisconsin (Vogt, 1981b). Most of the predation threat occurs in the nests as opposed<br />

to adult turtles. <strong>Ohio</strong> nest predators include raccoons (Procyron lotor), opossums,<br />

(Didelphis virginiana), coyote (Canis latrans), and foxes (Vulpes sp.). Hatchling<br />

emergence can also attract predation from Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), gulls<br />

(Larus delawarensis), red-winged black birds (Agelaius phoeniceus), grackles<br />

(Quiscalus sp.), and crows (Corrus brachyrhynchos). Bass (Micropterus sp.), Longnose<br />

Gar (Lepisosteus osseus), and catfish are possible predators in the water. Adults are<br />

protected from predators by the their shell, however, adult females can be captured and<br />

killed by raccoons on the nesting beaches as has been observed in other aquatic<br />

turtles. Leeches are common on the legs and shells of <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles.<br />

Conservation:<br />

The Scioto<br />

The disjunct distribution of the Scioto River <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle population<br />

makes it vulnerable and thus a population that requires periodic monitoring. <strong>Turtle</strong><br />

populations in general and emydid turtles in particular, are most sensitive to changes in

adult survivorship (Congdon et al., 1993; 1994). Thus, any factors that increase adult<br />

mortality are likely to threaten the Scioto population. Factors that can increase adult<br />

mortality include harvest, incidental bycatch in commercial gear, pollution, and habitat<br />

alteration. <strong>Map</strong> turtles may not be harvested in <strong>Ohio</strong> and thus harvest is not a potential<br />

problem. However, poaching due to increase demand in commercial markets could be<br />

a problem. Perhaps a greater threat to adult map turtles is mortality as bycatch from<br />

other gear designed to catch fish or other turtle species. Snapping and softshell turtles<br />

are legally harvested in <strong>Ohio</strong> and map turtles are caught in the same types of traps.<br />

Additionally, turtles frequently are caught on trot lines and therefore this fishing<br />

technique poses a threat to map turtles.<br />

Currently, the greatest threat to <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles in <strong>Ohio</strong> is Scioto River<br />

channelization and bank stabilization that reduces nesting, foraging, and basking<br />

habitat. Channelization and bank stabilization cause changes in the river flow regime<br />

that reduces the ability of the river to meander and thereby changes its hydrodynamics.<br />

Reducing meander and dynamic reduces tree falls and the dead wood necessary for<br />

basking and eliminates sand and gravel bars that are key nesting habitat. The<br />

decrease in habitat diversity may eliminate the preferred habitat of the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map<br />

turtle and increase competitive interactions with the sympatric congener, the northern<br />

map turtle. Correspondingly, the highest densities of map turtles found in the Scioto<br />

occur in areas with minimal channelization (Temple-Miller 2008). Additionally, climate<br />

change models predict decreased precipitation in <strong>Ohio</strong> suggesting that flood and<br />

drought patterns can change the flow and sediment distribution. Habitat recruitment<br />

and regeneration, particularly woody debris, may decrease large woody debris<br />

recruitment through scouring of banks may become difficult in low flow while high flows<br />

may flood basking habitat outside of the channel or further downstream. Woody debris<br />

recruitment is essential to their basking and foraging habitat. High flow and flashy<br />

conditions could alter the flow of organic matter, large woody debris, and change the<br />

biogeomorhology that could change rates of erosion, sedimentation, and the flow of<br />

organic particulates. One possible explanation for the isolation of <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtles<br />

in the Scioto River may be that the channelization and shipping have reduced suitable<br />

habitat that led to the extirpation of the Oauchita map turtle from the <strong>Ohio</strong> River.<br />

Because of this possibility, surveys of other tributaries along the <strong>Ohio</strong> River are needed<br />

to determine if other relictual populations of the <strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle occur in the vicinity<br />

of the <strong>Ohio</strong> River, particularly between the Scioto River and the nearest population in<br />

Indiana.<br />

Dams upstream of known map turtle habitats in the Scioto River habitat likely<br />

limit the natural river change and habitat creation although this large watershed is<br />

mostly natural south of Columbus, <strong>Ohio</strong>. During the summer of 2007, the Scioto River<br />

experienced two of the five lowest water records kept on web record (NOAA 2008). Yet<br />

in 2008, the river crested to historical levels; two of the twenty crest events on web<br />

record were also within the last year (NOAA 2008). Programs that attempt to restore<br />

agricultural land within the river corridor such as the Scioto Conservation Reserve<br />

Enhancement Program will become increasingly important to minimize runoff and<br />

erosion should flood events continue to rise. Given that this project includes the goal of<br />

restoring the natural meander and flood capability of the river, we anticipate that the<br />

habitat should improve for map turtles and that their populations could increase. Future<br />

river studies should monitor the changing landscape on a broad scale to develop a<br />

greater understanding of fluvial and ecological interactions.

Literature Cited<br />

Cagle, F.R. 1953. Two new subspecies of the genus <strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica.<br />

Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology. <strong>University</strong> of Michigan 546:1-17.<br />

Black, J.H., J. Pigg and R.L. Lardie.1987. Distribution records of <strong>Graptemys</strong> in<br />

Oklahoma. Bulletin of Maryland Herpetological Society 23: 65-68.<br />

Boyer, D.R. 1965. Ecology of the basking habitat in turtles. Ecology 46:99-118.<br />

Bull, J.J., R.C. Vogt.1981. Temperature-sensitive periods of sex determination in<br />

Emydid turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology 218:435-440.<br />

Bull, J.J., R.C. Vogt, and C.J. McCoy, 1982. Sex determining temperatures in turtles<br />

with environmental sex determination. Evolution 36: 326-333.<br />

Charnov, E.L. and J.J. Bull. 1989. The primary sex ratio under environmental sex<br />

determination. Journal of Theoretical Biology 139:431-436.<br />

Conant, R., M. B. Trautman, and E. B. McLean. 1964 The false map turtle, <strong>Graptemys</strong><br />

pseudogeographica (Gray) in <strong>Ohio</strong>. Copeia 1964: 212-213.<br />

Congdon, J. D., A. E. Dunham and R. C. van Loben Sels. 1993. Delayed sexual<br />

maturity and demographics of Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii):<br />

implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Conserv.<br />

Biol. 7:826-833.<br />

Congdon, J. D., A. E. Dunham and R. C. van Loben Sels. 1994. Demographics of<br />

common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina): implications for conservation of<br />

long-lived organisms. Am. Zool. 34:397-408.<br />

Ernst, C.H., R.W. Barbour, and J.E. Lovich. 1994. <strong>Turtle</strong>s of the United States and<br />

Canada. Washington and London. Smithsonian Institute Press. 403-409pp.<br />

Ewert, M.A. 1979. <strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica <strong>ouachitensis</strong> (<strong>Ouachita</strong> map turtle).<br />

Herpetological Review 10:102.<br />

Ewert, M.A. and C.E. Nelson. 1991. Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and<br />

some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991:50-69.<br />

Fuselier, L. and D. Edds. 1994. Habitat partitioning among three sympatric species of<br />

map turtles, Genus <strong>Graptemys</strong> . Journal of Herpetology 28:154-158.<br />

Gibbons, J.W., and J.E. Lovich. 1990. Sexual dimorphism in turtles with emphasis on<br />

the slider turtle (Trachemys scripta). Herpetological Monographs 4:1-29.<br />

Harvey, M.B. 1992. The distribution of <strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica on the upper<br />

Sabine River. Texas Journal of Science 44:505-510.<br />

Lindeman, P.V. 1999. Surveys of basking map turtles <strong>Graptemys</strong> sp. in three river<br />

drainages and the importance of deadwood abundance. Biological Conservation<br />

88:33-42.<br />

Moll, D. 1976. Food and feeding strategies of the Oauchita map turtle (<strong>Graptemys</strong><br />

pseudogeographica <strong>ouachitensis</strong>). American Midland Naturalist 96:478-482.<br />

Moll, D., and E.O. Moll. 2004. The Ecology Exploitation and Conservation of River<br />

<strong>Turtle</strong>s. New York. Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press. 393pp.<br />

NOAA. 2008. Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service, Scioto River.<br />

[web];“http://usasearch.gov/search?affiliate=noaa.gov&v%3Aproject=firstgov&qu<br />

ery=scioto+river”. (7/23/08).<br />

Pluto T.G. and E.D. Bellis. 1986. Habitat utilization by the turtle, <strong>Graptemys</strong><br />

geographica, along a river. Journal of Herpetology 22: 152-158.<br />

Pluto T.G. and E.D. Bellis. 1988. Seasonal and annual movements of riverine map<br />

turtles, <strong>Graptemys</strong> geographica, along a river. Journal of Herpetology 20:22-31.

Shively, S.H. and J.F. Jackson. 1985. Factors limiting the upstream distribution of the<br />

Sabine map turtle. American Midland Naturalist. 114:292-303.<br />

Smith, A.S. 2008. Phylogeography of <strong>Graptemys</strong> <strong>ouachitensis</strong>. (MS Thesis). Athens<br />

(OH): <strong>Ohio</strong> <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Smith, H.G. ,R.K. Burnard, E. E. Good. And J.M. Keener. 1973. Rare and<br />

endangered vertebrates of <strong>Ohio</strong>. The <strong>Ohio</strong> Journal of Science 73:257-265.<br />

Stephens, P.R. and J.J. Wiens. 2003. Ecological diversification and phylogeny of<br />

emydid turtles. Biological Journal of the Linnaean Society 79:577-610.<br />

Temple-Miller, K.G. 2008. Use of radiotelemetry and GIS to distinguish habitat use<br />

between <strong>Graptemys</strong> <strong>ouachitensis</strong> and G. geographica in the Scioto River. (MS<br />

Thesis). Athens (OH): <strong>Ohio</strong> <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Timken, R.L.1968. <strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica in the upper Missouri River of the<br />

northcentral United States. Journal of Herpetology 1:76-82.<br />

Tuberville, T.D., J.W. Gibbons, and J.L. Greene. 1996. Invasion of new aquatic<br />

habitats by male freshwater turtles. Copeia. 1996:713-715.<br />

Vogt, R.C. 1978. Systematics and ecology of the false map turtle complex <strong>Graptemys</strong><br />

pseudogeographica. (PhD Thesis). Madison (WI): <strong>University</strong> of Wisconsin-<br />

Madison.<br />

Vogt, R.C. 1979. Cleaning/feeding symbiosis between grackles (Quisscalus: Icteridae)<br />

and map turtles (<strong>Graptemys</strong>: Emydidae). Auk 96:609.<br />

Vogt, R.C. 1980. Natural history of the map turtles <strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica and<br />

G. <strong>ouachitensis</strong> in Wisconsin. Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 22:17-48.<br />

Vogt, R.C. 1981a. Food partitioning in three sympatric species of map turtle, Genus<br />

<strong>Graptemys</strong> (Testudinata, Emydidae). American Midland Naturalist 105:102-111.<br />

Vogt, R.C. 1981b.<strong>Turtle</strong> egg (<strong>Graptemys</strong>:Emydidae) infestation by fly larvae. Copeia<br />

1981:457-459.<br />

Vogt, R. C. 1993. Systematics of the false map turtle (<strong>Graptemys</strong> pseudogeographica<br />

complex: Reptilia, Testudines Emydidae). Annals of the Carneige Musuem<br />

Natural History 62:1-46.<br />

Ward, J.P. 1980. Comparative cranial morphology of the freshwater turtle subfamily<br />

Emydinae: An analysis of the feeding mechanisms and systematics.<br />

[dissertation]. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina State <strong>University</strong>.<br />

Webb, R.G. 1961. Observations on the life histories of turtles (genus Pseudemys and<br />

<strong>Graptemys</strong>) in Lake Texocoma, Oklahoma. American Midland Naturalist 65:193-<br />

214.