You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TERMS AND CONDITIONS<br />

All items in this catalogue are guaranteed to be genuine.<br />

A full refund will be given for any item found not to be as described, provided it is<br />

returned undamaged within 14 days and any work returned must be sent by registered,<br />

prepaid, first class post (airmail overseas) and must be fully insured.<br />

All items are in good condition unless otherwise stated. Sizes are given in both the<br />

standard Japanese and Western format (in inches).<br />

All prices are net; postage, packing and insurance are extra.<br />

No additional Value Added Tax will be charged to either UK or overseas customers.<br />

Any importation or customs duties will be the responsibility <strong>of</strong> the customer.<br />

Invoices will be rendered in £ sterling.<br />

Payment must be made in £ sterling, either in a personal cheque or inter bank transfer.<br />

We also accept Visa, Mastercard, Switch, and American Express.<br />

The title <strong>of</strong> the goods does not pass to the purchaser until the invoice has been paid in<br />

full.<br />

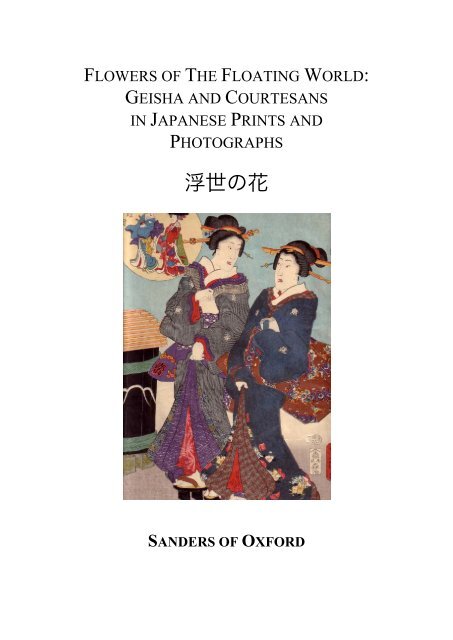

FRONT COVER: Detail from Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864), Hachidanme,<br />

from the 1859 series Chûshingura E-kyôdai [Cat. No. 1/VIII]

While the culture <strong>of</strong> the courtesan and that <strong>of</strong> the geisha was ostensibly distinct and sharply<br />

drawn, geisha in the licensed quarters being forbidden from engaging sexually with the yûjo<br />

or courtesan’s customers, the line was always somewhat blurred, the basis <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

confusion over the scope and tone <strong>of</strong> the latter’s pr<strong>of</strong>ession. As one pithy senryû [epigram]<br />

author put it, writing about geisha <strong>of</strong> a disreputable quarter: ‘First will she spread ~ second,<br />

how’s her voice?’ Despite this ambiguity, however, the two worlds were divided and<br />

discrete, this delineation being markedly expressed in attire, manner, training, housing,<br />

governmental bureaucracy and general public perception. To a geisha, the high-ranking<br />

courtesans were vulgar, flashy, and obvious ~ their eroticism openly displayed in their<br />

overly-elaborate, brightly coloured attire and complicated hairstyles (such as their multiple<br />

use <strong>of</strong> kogai or hair pins). The geisha, on the other hand, strove for an understated elegance<br />

known as iki, a ‘cool’, restrained sense <strong>of</strong> style, which could only be truly appreciated by a<br />

customer who was iki himself.<br />

In the woodblock prints featured in the exhibition, oiran (a generic terms for the highest<br />

class <strong>of</strong> courtesan; lit. ‘castle toppler’, in reference to the ease at which they could rid an<br />

infatuated daimyô [lord] <strong>of</strong> his estates) predominate, depicted both as themselves and in a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> roles, drawn principally from classical novel and epic. This conflation <strong>of</strong> famous<br />

courtesan with beloved literary archetype served to render what were, essentially, indentured<br />

entertainers and prostitutes, however artistically skilled, into figures <strong>of</strong> legend with no<br />

reference point to the <strong>of</strong>ten harsh, quotidian reality <strong>of</strong> the pleasure quarters, which, according<br />

to figures at the end <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century were riddled with syphilis and gonorrhoea<br />

(over 9, 000 Yoshiwara women suffering from the former in 1893 alone) [De Becker: 1899,<br />

p. 360].<br />

Indeed, the mythologizing <strong>of</strong> the ‘flowers <strong>of</strong> the floating world’ rooted early and continues<br />

to flourish today~ the <strong>of</strong>ten far from romantic reality as adroitly masked as it was in the early<br />

modern era. Included in our exhibition is a Meiji-period image by an anonymous<br />

photographer, which poignantly counterweights that myth: a rare portrait <strong>of</strong> an Okami-san [a<br />

proprietress <strong>of</strong> a teahouse]. Her world weary, resigned expression recalling lines penned a<br />

century earlier by the renowned literati Ôta Nampo (1749-1823) on the insubstantial, shifting<br />

ground underpinning the floating world:<br />

Courtesans <strong>of</strong> the Five Streets <strong>of</strong> the Quarter,<br />

Ten years adrift on an ocean <strong>of</strong> troubles,<br />

Released at twenty-seven with misguided dreams<br />

Ah! This bitter mirage <strong>of</strong> the brothels!<br />

[Trans. T. Clark]<br />

EARLY JAPANESE PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Anne Louise Avery<br />

The origins <strong>of</strong> photography in Japan can be traced to 1848, when a daguerreotype camera<br />

was imported by Ueno Shunnojo (1790-1851) through the island <strong>of</strong> Dejima, the Nagasaki<br />

enclave where Chinese and Dutch merchants were allowed to trade during the long period <strong>of</strong><br />

Japan’s ‘Seclusion Law’ or Sakoku (ca.1650-1854).<br />

It was within the scientific rather than artistic community that photography began to flourish.<br />

In 1853, a Dutch doctor and amateur photographer, Dr J. K. van den Broek, arrived to work<br />

at a Nagasaki hospital and started to instruct a number <strong>of</strong> Japanese in the daguerreotype and<br />

calotype techniques. His successor at the hospital in 1857, Dr J. L. C. Pompe van<br />

Meerdervoort, introduced the relatively new wet-plate process to two <strong>of</strong> his most talented<br />

chemistry students: Ueno Hikoma (1838-1904), Ueno Shunnojo’s son, who subsequently<br />

opened the first commercial photo studio in Japan in 1862, and Kyuichi Uchida who went on<br />

to take the first photographic portraits <strong>of</strong> the Meiji Emperor and Empress.

The earliest known authenticated images <strong>of</strong> a Japanese subject were a number <strong>of</strong><br />

daguerreotypes taken in the United States by the Baltimore photographer Harvey R. Marks<br />

(1821-1902) in 1851. Marks photographed some <strong>of</strong> the survivors from a Japanese shipwreck,<br />

who had been rescued and brought to San Francisco in 1851, notably 'Sam Patch' the cook.<br />

Sam Patch later returned in 1854 with Commodore Perry, whose intention was to force<br />

Japan to abandon her isolationist position and open up to trade with America. Perry’s <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

photographer, Eliphalet Brown, Jr (1816-1886), took over 200 daguerreotypes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

expedition, photographing a number <strong>of</strong> Japanese women, including one courtesan. Few <strong>of</strong><br />

these pictures are extant.<br />

The success <strong>of</strong> Perry’s mission led to the arrival in 1856 <strong>of</strong> US consul Townsend Harris<br />

together with a Dutch interpreter, Henry Heusken. Heusken was also a photographer, and<br />

among his students was Renjo Shimooka (1823-1914), who opened a studio in Yokohama in<br />

1862. Russia had also sent naval expeditions in 1853 and 1854, including a daguerreotypist,<br />

Captain Aleksander Mozhaiskii in 1854.<br />

Subsequent to these visits, the US, Russia and other Western countries negotiated the<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> 'treaty ports', including Yokohama, Hakodate and Shimoda.<br />

Following an American, Orrin E. Freeman, and an Englishman, William Saunders, Felice<br />

Beato (ca. 1825-ca.1908) arrived in Yokohama in around 1862, with an impressive<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional record [Cat. No. 52; 53]. His reputation quickly grew, during the 1860s being<br />

considered the foremost Western photographer in Japan, until the sale <strong>of</strong> his studio to Baron<br />

von Stillfried in 1877, ending his sojourn in Japan. Commercial photography in Japan owed<br />

much to Beato, particularly in the relation to the practice <strong>of</strong> hand-colouring prints ~ a<br />

process which brought the art <strong>of</strong> photography closer to the traditions <strong>of</strong> ukiyo-e woodblock<br />

prints.<br />

His successor, Baron Raimund von Stillfried-Ratenicz (1839-1911), an Austrian aristocrat,<br />

was one <strong>of</strong> the leading photographers <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century [Cat. No. 54]. Throughout<br />

the 1870s, he managed a series <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional studios in Yokohama, which was now firmly<br />

established as the premiere gateway for the Western tourist trade. As such, it supported and<br />

nurtured the rapid spread <strong>of</strong> commercial photography, the number <strong>of</strong> studios expanding<br />

rapidly. In the 1880s, the Yokohama shashin [‘Yokohama-style photograph’] entered its<br />

heyday: the shift from experimental dilettanteism to commercialism evident in the new<br />

production <strong>of</strong> souvenir photograph albums, replete with geisha, samurai, quaint peasantry<br />

and the omnipresent ‘Fujiyama’; sold to foreign tourists as virtual records <strong>of</strong> their<br />

experiences in the exotic and bewildering country.<br />

The tourist trade, however, was not the only marketplace in which the empiricism <strong>of</strong> early<br />

photography was utilised. From the 1870s to the mid-1880s, photographs <strong>of</strong> the inmates <strong>of</strong><br />

the Yoshiwara were displayed in frames outside <strong>of</strong> the respective brothels. Later, this<br />

practice was refined into the presentation <strong>of</strong> albums (mostly consisting <strong>of</strong> women from first<br />

and second-class houses) to prospective customers. Called Shashin mitate-chô (‘photograph<br />

albums to facilitate the selection <strong>of</strong> girls), one stated that ‘you can find any flower you desire<br />

if you go to the Yoshiwara. However, the practice <strong>of</strong> promenading…is too old a custom to<br />

be revived in these times, and so we have hit upon the plan <strong>of</strong> grouping a collection <strong>of</strong> belles<br />

in the space <strong>of</strong> a small photograph album…leaving our guests to select the flowers they<br />

fancy’ [From a photograph album <strong>of</strong> the Ohiko-rô].<br />

In this way, the Yokohama photograph entered the culture <strong>of</strong> the Floating World, its ability<br />

to objectively capture an image rendering it a dark modern successor to the idealised<br />

woodblocks still being printed in the Nihonbashi publishing houses: the shashin, literally<br />

meaning ‘truthful copy’, revealing the monetary sordidity <strong>of</strong> the pleasure districts in a way<br />

that the nishiki-e could never do.<br />

During this period, the principal and most prolific studios were those <strong>of</strong> Adolfo Farsari<br />

(1841-1898), whose reputation, according to Rudyard Kipling, extended ‘from Saigon even<br />

to America [Cat. No. 55],’ and the increasingly financially-successful Japanese photographic<br />

pioneers, led by Kimbei Kusakabe (1841-1934) [Cat. No. 51, 56, 57], Kazuma Ogawa<br />

(1860-1929) [Cat. No.: 58] and Kozaburo Tamamura (1856-1915).<br />

The ascendancy <strong>of</strong> Yokohama as a centre for photography began to wane at the close <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Meiji period (1868-1912), when advances in camera technology enabled amateurs affordably

I. Daiichinokan. Kiritsubo. [Chapter 1: The Paulownia Court]<br />

Date [Western]: 1858<br />

Date [Japanese]: Second Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: uma ni/horse 2<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Uoya Eikichi<br />

Carver: Yokogawa Takejiro<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock with karazuri<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e diptych<br />

Condition: Very good; some light creasing; pristine colour with the fugitive purple<br />

intact<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £550<br />

II. Daishichinokan E-awase [Chapter 17: The Picture Contest]<br />

Date [Western]: 1858<br />

Date [Japanese]: Second Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: uma ni/horse 2<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Uoya Eikichi<br />

Carver: Yokogawa Takejiro<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock with karazuri<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e diptych<br />

Condition: Excellent with fine karazuri; pristine colour with the fugitive purple intact<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £600<br />

III. Dainijûgonokan. Hotaru. [Chapter 25: Fireflies]<br />

Date [Western]: 1858<br />

Date [Japanese]: Seventh Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: uma shichi/horse 7<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Wakasaya Yoichi<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print with karazuri<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e diptych<br />

Condition: Excellent with fine karazuri; pristine colour with the fugitive purple intact<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £600<br />

IV. Daisanjûnokan. Fujibakama. [Chapter 30: Purple Trousers]<br />

Date [Western]: 1858<br />

Date [Japanese]: Second Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: uma ni/horse 2<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Uoya Eikichi<br />

Carver: Yokogawa Takejiro<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print with karazuri<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e diptych<br />

Condition: Excellent with fine karazuri; pristine colour with the fugitive purple intact

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £550<br />

V. Daiyonjûnikan. Niou no Miya. [Chapter 42: His Perfumed Highness]<br />

Date [Western]: 1859<br />

Date [Japanese]: Ansei 6<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Censor/Zodiacal Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined’] and date seal [yagi<br />

ichi/goat 1]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Ebisu-ya Shôshichi<br />

Carver: Yokogawa Takejiro<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print with karazuri<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e diptych<br />

Condition: Excellent with fine karazuri; pristine colour with the fugitive purple intact<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £550<br />

3. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Blossom Viewing [Hanami]<br />

Series: Tôsei Genji [Modern Day Genji]<br />

Date [Western]: 1859<br />

Date [Japanese]: 10 th Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 6<br />

Censor/Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined] and zodiacal date seal [yagi jû/goat<br />

10]<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Ki-ya Sojiro<br />

Carver: Kosen<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Excellent<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 9 3/4 inches<br />

Price [Framed]: £750<br />

This rare triptych, similarly drawing on the rambunctious Inaka Genji gôkan, depicts<br />

Mitsuuji [Genji] in elaborate cold weather attire watching an inebriated group <strong>of</strong> spring<br />

revellers frolic under the blossom, the court ladies accompanying him closely resembling a<br />

courtesan and her kamuro. Dominating the composition, his exaggerated stature recalls lines<br />

from ‘The Festival <strong>of</strong> the Cherry Blossoms’ [Hananoen], Chapter 8 <strong>of</strong> Genji monogatari,<br />

describing the prince at a hanami party: ‘Genji dressed himself with great care…He wore a<br />

robe <strong>of</strong> thin white Chinese damask with a red lining and under it a very long train <strong>of</strong><br />

magenta. Altogether, the dashing young prince, he added something new to the assembly<br />

that so cordially received him…He quite overwhelmed the blossoms, in a sense spoiling the<br />

party.’<br />

4. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Admiring Suzumushi [Bell Crickets] on a Summer Evening<br />

Date [Western]: 1860<br />

Date [Japanese]: Tenth month <strong>of</strong> Man-en 1/Ansei 7<br />

Signatures: Toyokuni-ga [middle and right-hand panels]; Kunihisa-ga [left-hand<br />

panel]<br />

Censor/Date Seal: Combined aratame-date seal [saru jû/monkey 10]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Moriya Jihei

6. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Yatsu koane tenen no zu [Eight Princesses from the Tales <strong>of</strong> the Dog Warriors]<br />

Series: Satomi Hakkenden Sôkanbi [The Final Chapter <strong>of</strong> the Tales <strong>of</strong> the Eight Dog<br />

Warriors from Satomi]<br />

Date [Western]: 1855<br />

Date [Japanese]: Twelfth Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 2<br />

Signature: oju Toyokuni-ga<br />

Censor Seal: aratame [‘examined’]<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: usagi jûni/hare 12<br />

Carver: Sashichi<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print with karazuri [‘blind printing’]<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Good; some creasing on left-hand sheet; fugitive purple intact<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 3/4 x 9 3/4 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £650<br />

A rare triptych depicting the usually neglected female characters from the Nansô Satomi<br />

Hakkenden by Takizawa Bakin (1767-1849), a series <strong>of</strong> 106 yomihon published between<br />

1814 and 1841. The tales, their complex plot-lines structured around bushi notions <strong>of</strong> heroic<br />

courage, duty, honour, filial piety, righteousness, and unflinching physical prowess,<br />

originally deriving from the Chinese novel Shuihuzhuan [The Water Margin; Japanese:<br />

Suikoden].<br />

The story begins with Satomi Yoshizane <strong>of</strong>fering his beloved daughter Fusehime to<br />

whomever can manage to kill his sworn enemy. In a strange twist <strong>of</strong> fate, Yatsufusa, his<br />

faithful dog, murders the odious man, returning with his severed head. Against her distraught<br />

father’s wishes, Fusehime subsequently accepts the hound as her husband, submitting to the<br />

winds <strong>of</strong> karma. Eventually a child is born to the unlikely pairing. After the birth, a vassal <strong>of</strong><br />

Yoshizane attempts to kill Yatsufusa, but, instead, his bullet strikes Fusehime who then<br />

commits suicide. On the moment <strong>of</strong> death, eight magical tei beads, each inscribed with a<br />

character signifying a Confucian virtue, fly up to the heavens and vanish. They are later<br />

discovered in the clutched hands <strong>of</strong> infant sons born to families whose names begin with inu,<br />

the kanji for dog.<br />

Once grown, these eight young ‘dog’ warriors, the spiritual <strong>of</strong>fspring <strong>of</strong> the tragic Fusehime,<br />

engage in numerous heroic exploits, eventually restoring the dispossessed Satomi family to<br />

power. The huge canvas painted by the loquacious Bakin ensured its popularity as rich<br />

source <strong>of</strong> imagery for ukiyo-e warrior prints [musha-e] and mitate-e. This work, a form <strong>of</strong><br />

gentle mitate-e, is interesting for its exclusive focus on the wives and daughters <strong>of</strong> the series;<br />

as usual, portrayed by famous tayû <strong>of</strong> the day.<br />

The grouping consists <strong>of</strong> the following characters: Shizuo-hime [1 st Princess, Shinbee's wife]<br />

Kinoto-hime [2 nd Princess, Sôsuke’s wife]; Hinaki-hime [3 rd Princess, Daikaku’s wife];<br />

Takeno-hime [4 th Princess, Dôsetsu’s wife]; Onami-hime [7 th Princess, Keno’s Wife]; Irotohime<br />

[8 th Princess, Kobungo’s wife]; and two Senior Ladies in Waiting [Rôjo].<br />

The byôbu decorated with auspicious cranes and the mass <strong>of</strong> plum blossom in the centre <strong>of</strong><br />

the composition indicates the early spring.<br />

7. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Cherry Trees at Night [Yozakura]<br />

Date [Western]: 1860<br />

Date [Japanese]: Second Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 7<br />

Censor/Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined’] and zodiacal date seal [saru<br />

ni/monkey 2]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Shimizu-ya Naôjirô<br />

School: Utagawa

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Excellent; slight wear at edges <strong>of</strong> sheets<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £875<br />

Almost identical in design to an earlier triptych <strong>of</strong> 1850, Viewing Plum Blossoms at Night<br />

[Okonomi yoru no umemi], this rare triptych is one <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> works depicting hanami<br />

[blossom viewing] in the capital. In the Edo imagination, the beauty and brevity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cherry blossom was synonymous with the transient pleasures <strong>of</strong>fered by the Floating World.<br />

Aside from the Shin Yoshiwara, where cherry trees were specially planted for the flowering<br />

season, four places were most frequented for hanami parties: Ueno, Gotenyama, Asukayama<br />

and the banks <strong>of</strong> the Sumidagawa [Sumida River]. The river was particularly popular for<br />

moonlit strolls among the fragrant blossoms, a picturesque theme frequently explored by<br />

ukiyo-e artists.<br />

The sakura fever that overtook Japan every spring was parodied in one famous geisha kouta<br />

[a short, lyrical song accompanied by the shamisen], popular in Kunisada’s day:<br />

Sakura sakura to O the cherry, the cherry,<br />

Hitobito ga When is it that folks<br />

Ukaretamau wa Frolic about under the blossom?<br />

Itsu no koto From the end <strong>of</strong> the Third Month<br />

Sangatsu sue To the middle <strong>of</strong> the Fourth,<br />

Kara shigatsu It’s nothing<br />

No nakareba kana but cherry blossom!<br />

Hanazakari<br />

8. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Kachô noriai genji [Prince Genji partnered with Birds and Flowers]<br />

Date [Western]: 1859<br />

Date [Japanese]: Eighth Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 6<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga within a toshidama cartouche<br />

Censor/Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined’] and zodiacal date seal [yagi<br />

hachi/goat 8]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Kaga-ya Kichiemon<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print with karazuri [‘blind printing’]<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Excellent<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £850<br />

The ‘modern’ Genji floats down a river on a yakatabune [palace boat] accompanied, as<br />

usual, by a coterie <strong>of</strong> ladies. Cherry trees in bloom represent the ‘partnership’ <strong>of</strong> the title and<br />

refer to the evanescent nature <strong>of</strong> such delightful entertainment. Contrasting with his party’s<br />

elegance, is a regular river barge, filled with lower-class, slightly rusticated entertainers who<br />

have obviously come from a spring matsuri. The costume being roughly shoved away for its<br />

inhabitant to smoke a pipe, is that <strong>of</strong> an oni or demon.<br />

Guardians <strong>of</strong> the entrance to hell, the horned, shaggy-haired and club-wielding oni, were<br />

usually considered a powerfully malevolent force. However, like the shape-shifting kitsune<br />

[fox], they were <strong>of</strong>ten capricious in their relationship with humanity ~ occasionally<br />

performing good deeds or <strong>of</strong>fering unexpected assistance. Such unpredictable fluxes <strong>of</strong> good<br />

and bad behaviour made appropriate obeisances necessary and every spring oni-odori<br />

[demon dances] would take place around the country. At the beginning <strong>of</strong> the second month

it was also traditional to cast dried beans [signifying prosperity] in a dwelling’s nooks and<br />

crannies to drive any resident recalcitrant oni away.<br />

9. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864) and Utagawa Hiroshige<br />

(1797-1858).<br />

Azuma Genji Yuki no Niwa [The Eastern Genji in the Snowy Garden]<br />

Date [Western]: 1854<br />

Date [Japanese]: Twelfth Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 1<br />

Signatures and Artist’s Inscriptions/Seals: Toyokuni-ga in a toshidama cartouche [left<br />

and right-hand sheets]; Yuki no kei oju [‘The Snow Scene on Request’]; Hiroshige-hitsu<br />

with Ichiryusai seal<br />

Censor Seal: Aratame [‘examined’]<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: tora jûni/tiger 12<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Moriji<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Excellent; particularly fine colour and bokashi<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £1, 650<br />

This collaborative design, showing Genji and Murasaki watching a group <strong>of</strong> maids building<br />

a yuki-usagi [snow rabbit], consists <strong>of</strong> a landscape background by Hiroshige, with figures by<br />

Kunisada. Although the genji mon forming the cartouche in the right-hand sheet is that <strong>of</strong><br />

Chapter 12 <strong>of</strong> Genji monogatari, the construction <strong>of</strong> a snow sculpture that forms the central<br />

motif <strong>of</strong> the work, seems to bear a closer relationship to an <strong>of</strong>t-depicted passage in Chapter<br />

20, Asagao [Morning Glory]:<br />

‘There was a heavy fall <strong>of</strong> snow. In the evening there were new flurries. The moon turned<br />

the deepest recesses <strong>of</strong> the garden into a gleaming white. The contrast between the snow on<br />

the bamboo and the snow on the pines was very beautiful...The flowerbeds were wasted, the<br />

brook seemed to send up a strangled cry, and the lake was frozen and somehow terrible. Into<br />

this austere scene, Genji sent little maidservants, telling them that they must make snowmen.<br />

Their dress was bright and their hair shone in the moonlight. The older ones were especially<br />

pretty…the fresh sheen <strong>of</strong> their hair black against the snow. The smaller ones quite lost<br />

themselves in the sport…It was all very charming.’ [Seidensticker, trans., 1976: p.357].<br />

In Japanese cosmology, the quasi-divine figure <strong>of</strong> the white rabbit was thought to embody<br />

the spirit <strong>of</strong> the moon; the god <strong>of</strong> the moon and the seasonal tides, Tsuki-Yomi, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

depicted as riding a giant usagi. As such, the construction <strong>of</strong> a snow rabbit in the moonlit<br />

garden would have been particularly appropriate. That the maid servants are shown placing<br />

the final eye in the rabbit is <strong>of</strong> import, as its recalls the Buddhist eye-opening ceremony<br />

[kaigen], based on the tenet that a wooden or painted image can only embody its signified<br />

divinity when the eyes are painted in. Kaigen <strong>of</strong>ten drew huge crowds <strong>of</strong> people, in 752, for<br />

example, when a large bronze image <strong>of</strong> Roshana (Mahavairocana) was dedicated in the main<br />

hall <strong>of</strong> Todai-ji in Nara, the Buddha's eyes being painted in by an Indian monk, it was<br />

witnessed by roughly ten thousand priests and numerous foreign visitors.<br />

10. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Yukimi tsuki [Snow Viewing Month]<br />

Series: Genji Jûnikagetsu no uchi [The Twelve Months <strong>of</strong> Genji]<br />

Date [Western]: 1856<br />

Date [Japanese]: Seven Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 3<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga in a toshidama cartouche<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: tatsu shichi/dragon 7<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Fujioka-ya Keijirô<br />

School: Utagawa

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Excellent with especially fine colour and detailing<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £1, 650<br />

This important and rare work <strong>of</strong>fers a further reinterpretation <strong>of</strong> Chapter 20 <strong>of</strong> Genji<br />

monogatari, with the erection <strong>of</strong> a snow frog [yuki-kaeru] being substituted for the yukiusagi.<br />

Genji, surrounded by courtiers, points his kiseru [pipe] at the group energetically<br />

putting the finishing touches to the sculpture. Again, the moment is that <strong>of</strong> the placement <strong>of</strong><br />

the final eye, the ritualised awakening and ensouling <strong>of</strong> the image.<br />

In Japanese the word for "frog" and the verb for "to return" are pronounced the same way<br />

[kaeru], and, in the floating world, it became customary for a geisha or courtesan to fold and<br />

pin up an origami frog after entertaining a favourite patron, in the hope that he would return.<br />

A further semantic layer is <strong>of</strong>fered by the Zen notion that the characteristic squatting position<br />

<strong>of</strong> the frog was reminiscent <strong>of</strong> a monk’s meditation or zazen position; the Rinzai Zen master<br />

Sengai Gibbon (1750-1837), for example, executing numerous sumi-e sketches on that<br />

theme. Thus, as with most ukiyo-e, all is not quite as it seems ~ the playful snow frog<br />

actually being positioned in the apposite pose for the achievement <strong>of</strong> satori or<br />

enlightenment: the awareness <strong>of</strong> the transience <strong>of</strong> all things, a constant <strong>of</strong> both Genji and<br />

ukiyo culture, being conflated with the asobi [play] <strong>of</strong> Genji and companions in the snow. As<br />

one <strong>of</strong> Genji’s waka from Chapter 20 expresses, in the midst <strong>of</strong> pleasure, the sadness <strong>of</strong> this<br />

world <strong>of</strong> fragile appearances, the old sense <strong>of</strong> ukiyo, can suddenly intrude. Admiring the<br />

beauty <strong>of</strong> Murasaki against the backdrop <strong>of</strong> the snowy garden, his thoughts are interrupted<br />

by the call <strong>of</strong> a waterfowl: ‘A night <strong>of</strong> drifting snow and memories/Is broken by another note<br />

<strong>of</strong> sadness.’<br />

11. Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)<br />

The Shin Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarter<br />

Date [Western]: 1861<br />

Date [Japanese]: First Month <strong>of</strong> Man-en 2<br />

Signature: Kunisada-ga<br />

Censor/Zodiacal Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined’] and date seal [tori ichi/<br />

cock 1]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Chôkichiban [rare]<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 1/2 inches<br />

Condition: Good<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £850<br />

The Shin Yoshiwara [‘New Yoshiwara’] pleasure quarter represented the nexus <strong>of</strong> the<br />

floating world. It was named for the marshy reed plains near Nihonbashi where it was<br />

originally established, by Shouji Jin'emon (1576-1644), at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the seventeenth<br />

century, the only bakufu sanctioned prostitution zone in Edo. Almost immediately, however,<br />

the first kanji ‘reed’, was replaced by that for ‘happiness’, which shares the same reading;<br />

transfiguring the meaning to the more appropriate and appealing ‘Plain <strong>of</strong> Happiness’. In<br />

1657, a terrible fire swept through the enclosed district, and the quarter was moved to a new<br />

site by the Nihon-zutzumi dyke in the Asakusa district, thus adding the prefix Shin or ‘New’<br />

to the name. After its relocation, the quarter began to flourish; its initial five-street layout<br />

expanding to seven to accommodate the growing population, which, in its heyday in the<br />

early eighteenth century, numbered over 3000 courtesans and kamuro. In addition to the<br />

women, a daily carnival <strong>of</strong> brothel owners, shopkeepers, geisha, cooks, servants, attendants,

entertainers, musicians and ‘adventurers and intermediaries <strong>of</strong> every kind and description’<br />

plied the wards for trade [Turk, 1966: p.135].<br />

Despite the otherworldly isolation <strong>of</strong> the quarter and the emphasis on a client’s monetary<br />

assets rather than his rank, the Yoshiwara nevertheless developed an elaborate system <strong>of</strong><br />

precedence and etiquette as bewildering and stifling as that which dictated the ‘fixed’ world<br />

outside. This, together with the spiralling costs <strong>of</strong> hiring a high-class tayû or kôshi, led to the<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> numerous okabasho or unlicensed, illegal pleasure districts where the average<br />

townsman could afford a more quotidian and unadorned form <strong>of</strong> prostitution.<br />

Indeed, by the end <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century, the highest ranks <strong>of</strong> courtesan occupied such a<br />

super-elevated and financially unobtainable position that the grading system had to be<br />

changed ~ the lower yobidashi and chûsan classes moving to the top. [Clark, 1992: p.15]. As<br />

grand courtesans, they occupied houses known as ômagaki after the distinctive lattice<br />

windows at the entrance. Higher graded women were not expected to display themselves to<br />

attract clients, however, instead elegantly processing, retinue <strong>of</strong> kamuro in matching kimono<br />

trailing behind them, to an ochaya [‘teahouse’] to meet the prosperous customer who had<br />

ceremonially summoned them.<br />

Just such a procession can be seen in the right-hand sheet <strong>of</strong> Kunisada II’s triptych, which<br />

depicts nine <strong>of</strong> the most famous courtesans in the Shin Yoshiwara; the decorative cartouche<br />

containing their mon or device, name and a short poetic encomium.<br />

The pyramidal arrangement <strong>of</strong> buckets [in the centre sheet] was a safeguard against the everpresent<br />

danger <strong>of</strong> fires, so common they were known as ‘Flowers <strong>of</strong> Edo’.<br />

12. Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)<br />

A Collection <strong>of</strong> Ôiran inside the Shin Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarters<br />

Date [Western]: 1861<br />

Date [Japanese]: First Month <strong>of</strong> Man-en 2<br />

Signature: Kunisada-ga<br />

Censor/Zodiacal Date Seal: Combined aratame [‘examined’] and date seal [tori ichi/<br />

cock 1]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Chôkichiban [rare]<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Condition: Good<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 14 x 9 1/2 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £850<br />

From the same series as the above triptych, the viewer’s perspective has now shifted to<br />

inside the Yoshiwara. Similarly acting as an idealistic advertisement for the exquisite and<br />

cultivated women on <strong>of</strong>fer, the work depicts a further set <strong>of</strong> nine courtesans, with their<br />

kamuro, languidly engaged in whiling away the time before their next assignations. In these<br />

types <strong>of</strong> unproblematic depictions, little was evoked, however, <strong>of</strong> the seamier and more<br />

pitiful side <strong>of</strong> the floating world.<br />

For the large numbers <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten pre-pubescent peasant girls sold into prostitution by their<br />

impoverished families, the best they could hope for was to become apprenticed as attendants<br />

to one <strong>of</strong> the more successful and high-ranking women. In an almost identical pattern to<br />

geisha, they were trained for a number <strong>of</strong> years in etiquette and the fine arts, finally making<br />

their debut as shinzô (the equivalent to maiko), apprentice courtesans, in their later teens.<br />

Thereafter, the aim was to progress through the hierarchy as rapidly as possible, moving<br />

from heya-mochi (having their own room) and zashiki-mochi (having their own suite) to<br />

becoming a full courtesan with servants <strong>of</strong> their own. After the standard decade <strong>of</strong> indenture,<br />

however, the options became rather limited for most women, however beautiful or talented.<br />

Possibly the happiest outcome <strong>of</strong> one’s Yoshiwara career would be societal and financial<br />

redemption by a kind patron, either by becoming his mistress or by running a business<br />

backed by his gold. All too many former inmates, however, ended their careers in the less

Publisher’s Seal: Sadaoka<br />

School: Hokusai<br />

Method: Woodblock surimono; hôsho-gami; embossed background; extensive<br />

detailing in gold [rich brass] and silver [zinc-rich brass].<br />

Format: Shikishiban<br />

Dimensions: Each impression 8 x 7 1/2 inches<br />

Code: BH163<br />

I. Green cartouche, bright red detailing on fan. Some oxidation.<br />

Price [Mounted]: £490<br />

II. Gold cartouche, faded red detailing on fan. Some soiling and movement <strong>of</strong> colour.<br />

Price [Mounted]: £450<br />

The exquisitely elegant and iki [‘cool’] bijin depicted in the upper roundel is probably a<br />

portrait <strong>of</strong> a geisha who was a particular favourite <strong>of</strong> the kyôka poet. This would seem to be<br />

confirmed by the presence <strong>of</strong> a fanciful boat-shaped form <strong>of</strong> the character nao, the first kanji<br />

<strong>of</strong> the poet’s name, Naonari Asa-no-ya, both on her fan and on the poetry slip to the right <strong>of</strong><br />

the composition. Naonari’s verse alludes to the central emblem <strong>of</strong> the auspicious kujaku or<br />

peacock, a bird <strong>of</strong>ten invoked in New Year surimono. It reads 'Tori mo kite asobu hikage no<br />

nagaki o ni kogane iro masu tama no hatsuharu' [‘The bird come and plays, and the jewelled<br />

early spring gilds the long tails <strong>of</strong> the sunbeams]. Interestingly, there was also a well-known<br />

poetic association between the peacock and the Shin Yoshiwara. At the end <strong>of</strong> the paddyfields<br />

behind the quarter, there was situated an old row <strong>of</strong> houses known as the Kujakunagaya<br />

(nagaya being a long building with several separate residences). From this rather<br />

lowly spot, the brilliant spectacle <strong>of</strong> the pleasure quarters could be seen to great advantage ~<br />

the spot thus being compared to the humble body <strong>of</strong> a peacock, with the dazzling splendour<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Yoshiwara as its magnificent tail.<br />

The two impressions <strong>of</strong> Bijin to kujaku in the exhibition demonstrate both the variations in<br />

tone, colour and decoration possible within the small print run <strong>of</strong> the surimono, and the<br />

problems <strong>of</strong> pigment experimentation in terms <strong>of</strong> long-term preservation.<br />

19. Yanagawa Shigenobu (1786-1832)<br />

Ume [Plum Blossom]<br />

Series: Sanfukyûkaigô [Series <strong>of</strong> Three Ladies]<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1820s<br />

Date [Japanese]: Bunsei era<br />

Signature: Artist’s seal<br />

Carver: Tani Seikô [?]<br />

School: Hokusai<br />

Method: Woodblock surimono<br />

Format: Shikishiban<br />

Condition: Fading and rubbing, otherwise good<br />

Dimensions: 8 x 9 inches<br />

Code: BH162<br />

Price [Mounted]: £380<br />

Shigenobu was a pupil <strong>of</strong> Hokusai, whose daughter he married, subsequently becoming<br />

adopted into the family. After marital problems forced a separation, however, he returned to<br />

his own family in Honjo Yanagawa. From the 1810s, he designed approximately thirty<br />

surimono, mainly for the Tsuru-ren or ‘Crane Group’, and was active as an illustrator <strong>of</strong><br />

yomihon and kyôka poetry anthologies.<br />

Two kyôka verses decorate this shunkyô [Spring Season] surimono, the first, by Senyôtei<br />

Zenko, extols the beauty <strong>of</strong> the ume blossom. The bijin’s robes are decorated with various<br />

botanical motifs, including irises and wisteria.

Dimensions: 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £200<br />

This relatively rare erotic bijin-ga is one <strong>of</strong> a twelve-print soroimono matching oiran to the<br />

different signs <strong>of</strong> the zodiac and, by extension, to the months <strong>of</strong> the year. Here, representing<br />

the sign <strong>of</strong> the dog or inu, a courtesan is shown tying her koshimaki [lit. ‘hip wrap’ or ‘waist<br />

roll’]. In early modern Japan, women did not wear underclothing: the tight lines <strong>of</strong> the<br />

kosode being ruined by superfluous material. Comprising a two-yard length <strong>of</strong> thin silk, the<br />

koshimaki constituted the most intimate layer <strong>of</strong> clothing and was simply wrapped around<br />

the waist.<br />

23. Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) (1786-1864)<br />

The Meandering Stream Party [Kyokusui no en or Kyokusui-no-Utage]<br />

Date [Western]: 1852<br />

Date [Japanese]: Sixth Month <strong>of</strong> Kaei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: ne roku/rat 6<br />

Nanushi Censor Seals: Murata [Murata Heiemon] & Muramatsu [Muramatsu<br />

Genroku]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Mori-ji<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Good, some wear at corners<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £500<br />

A mitate or parody <strong>of</strong> rantei kyokusui [Chinese: Lanting qushui] or ‘meandering stream and<br />

orchid pavilion’, a iconographical theme which referred to a gathering held in 353 by the<br />

famous Eastern Jin calligrapher Wang Xishi (Japanese: Ou Gishi [321-79]) at the Orchid<br />

Pavilion (Japanese: Rantei) in Guiji, Zhejiang. In order to celebrate the annual ‘Spring<br />

Purification Festival’ (held on the Third Day <strong>of</strong> the Third Month), Wang Xishi invited fortyone<br />

scholar-poets to engage in poetry and drinking while seated along the bank <strong>of</strong> a winding<br />

rivulet. As an elegant conceit, he arranged for servants to float cups <strong>of</strong> wine down the<br />

stream, and those guests who had not yet written a poem before a cup had passed by were<br />

required to imbibe a penalty cup. The next day, Wang assembled the surprisingly competent<br />

poems <strong>of</strong> his inebriated friends and wrote his famous Lanting jixu (Japanese: Rantei Shûjo)<br />

or ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Compilation’, a melancholy discourse on the meaning <strong>of</strong><br />

life.<br />

The trope became extremely popular in Chinese painting, and was subsequently equally<br />

revered by the Japanese. According to both the Nihon shoki and archaeological remains, a<br />

meandering stream built <strong>of</strong> stones was constructed in the southeast corner <strong>of</strong> the eightcentury<br />

Heijô palace, presumably so that aristocrats could re-enact the ‘meandering stream<br />

party’ (kyokusui-no-en).<br />

Paintings <strong>of</strong> rantei kyokusui typically feature a number <strong>of</strong> erudite gentlemen seated beside a<br />

twisting stream. For Sinophile Japanese painters the theme was symbolic <strong>of</strong> refined scholarly<br />

pleasure and the humour in Kunisada’s work rests heavily on that perceived esoteric<br />

aestheticism.<br />

The triptych wittily and somewhat irreverently depicts one such re-enactment with a group<br />

<strong>of</strong> fashionable 1850s bijin (beautiful women) and an exquisitely dressed samurai carrying a<br />

pipe (probably a pictorial nod towards Prince Genji, although the text does not make this<br />

association explicit); the jovial vulgarity <strong>of</strong> the servants wading in the water possibly<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering an indication <strong>of</strong> Kunisada’s opinion <strong>of</strong> the pretentiousness <strong>of</strong> such gatherings.

Notable paintings <strong>of</strong> the theme include works by Kanô Sansetsu (1589/90-1651), Nakayama<br />

Kôyô (1717-80) and Yosa Buson (1716-84).<br />

24. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Scene from Hatsune [The First Warbler or The First Song], Chapter 23 <strong>of</strong> Genji<br />

monogatari [The Tale <strong>of</strong> Genji]<br />

Series: Genji gojûyon jô [Fifty-four Pictures <strong>of</strong> Genji]<br />

Date [Western]: 1852<br />

Date [Japanese]: Fifth Month <strong>of</strong> Kaei 5<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga<br />

Nanushi Censor Seal: Hama Yahei<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Sanoki<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Chûban<br />

Condition; Good, some wear and fading<br />

Dimensions: 9 3/4 x 7 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £175<br />

This very short chapter in the Genji monogatari centres around an exchange <strong>of</strong> New Year’s<br />

greetings between Genji and the ladies <strong>of</strong> the Rokujô Mansion: Lady Murasaki [Murasaki no<br />

Ue] the Akashi Lady [Akashi no Ue], the Lady <strong>of</strong> the Orange Blossoms [Hanachirusato], the<br />

Safflower Lady [Suetsumuhana], and the Lady <strong>of</strong> the Locust Shell [Utsusemi]. In the<br />

chapter, Genji receives felicitous New Year delicacies in ‘bearded baskets’ [higeko, baskets<br />

with the ends <strong>of</strong> the woven strands left untrimmed] and, as depicted here, a warbler [uguisu]<br />

on an artificial pine branch, sent by the Akashi Lady, with whom he has a daughter, the<br />

future Akashi Empress [lower left]. Attached to the branch is a letter with a melancholy<br />

poem telling <strong>of</strong> her loneliness. Hatsune motifs are a constant <strong>of</strong> Japanese iconography,<br />

particularly within the decorative arts, because <strong>of</strong> their perceived auspicious symbolism.<br />

25. Utagawa Kunisada [Utagawa Toyokuni III] (1786-1864)<br />

Tori no koku [The ‘Hour’ <strong>of</strong> the Cock: 5 to 7 pm]<br />

Cartouche: A Group <strong>of</strong> Edoites by Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900)<br />

Series: Shunyu jûniji [Twelve Hours <strong>of</strong> Spring Pleasure]<br />

Date [Western]: 1856<br />

Date [Japanese]: Third Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 3<br />

Signature: Toyokuni-ga<br />

Censor Seal: aratame [‘examined’]<br />

Zodiacal Date Seal: tatsu san/dragon 3<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Yamaguchiya Tobei<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock<br />

Format: Single sheet ôban tate-e<br />

Condition: Excellent<br />

Dimensions: 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £375<br />

In Edo-period Japan, time was not measured in equal units, like the occidental hour. Instead,<br />

a day was split into day and night time, in accordance with sunrise and sunset, and then<br />

subsequently sub-divided into a further six segments, which, apart from at the two<br />

equinoxes, were unequal. The twelve ‘hours’ thus produced corresponded to the zodiacal<br />

animals used in calendrical numeration,<br />

Kunisada’s 1856 series explores and contrasts a courtesan’s day with that <strong>of</strong> the generic Edo<br />

chônin [townsmen], the latter being depicted in dinner-time scramble within a separate

Censor Seal: Kiwame [‘approved]<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Eikyudo (also known as Yamamoto-ya Heikichi)<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Single sheet ôban tate-e<br />

Condition: Excellent with fine detailing<br />

Dimensions: 15 x 9 3/4 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £600<br />

A courtesan surrounded by the aki-no-nanakusa or ‘Seven Plants <strong>of</strong> Autumn’, the boundary<br />

between her kosode and obi rendered deliberately faint, thus suggesting that she too<br />

represent a seasonal bloom. The plants consisted <strong>of</strong> hagi [bushclover], susuki [pampas<br />

grass], kikyô [Chinese bellflower], kuzu [arrowroot] ominaeshi [maidenflower], nadeshiko<br />

[pinks or wild carnations] and fujibakama [boneset].<br />

First mentioned collectively in a poem by Yamanoue no Okura (ca. 660-733) from the<br />

eighth-century Man’yôshû [ca. 750], they were <strong>of</strong>ten contrasted with the ‘Seven Grasses <strong>of</strong><br />

Spring’ or haru-no-nanakusa. According to De Becker [1899: p.226], yûjo <strong>of</strong> the Yoshiwara<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten set out artificial representations <strong>of</strong> the aki-no-nanakusa in their rooms, the displays<br />

intending to evoke autumnal fields, thus setting a wistful seasonal atmosphere for their<br />

customers.<br />

28. Kikugawa Eizan (1787-1867)<br />

Flirting in the Street <strong>of</strong> Fabric Shops, Odemmachô Quarter<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1840s<br />

Date [Japanese]: Tempô era<br />

Signature: Kikugawa Eizen-hitsu<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Aizuri-e woodblock<br />

Format: Single sheet ôban tate-e<br />

Condition: Good, some fading and slight rubbing on corners<br />

Dimensions: 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £480<br />

The fabric sellers’ quarter in Edo was centred on Momendana [‘The Great Post Station’], as<br />

the First Street in the Odenmachô was popularly known. Situated next to the Nihonbashi<br />

[‘The Bridge <strong>of</strong> Japan’], the departure point for journeys along the Tôkaidô and the hub <strong>of</strong><br />

mercantile Edo, Momendana had been associated with textiles from the Genroku period. By<br />

Eisen’s day, First Street boasted around fifty wholesale stores, stretching in an unbroken line<br />

on either side <strong>of</strong> the road, each business identifiable only by curtains [noren] emblazoned<br />

with the trader’s name.<br />

In Eisen’s print, possibly once part <strong>of</strong> a triptych, a cross-section <strong>of</strong> Shitamachi [‘Low City’]<br />

life bustles along the Momendana: a townswoman selects rolls <strong>of</strong> material from an eager<br />

salesman, a beauty dressed in a seasonal iris-patterned kosode (indicating the Fifth Month),<br />

flanked by her maids, flirts with a handsome samurai, holding a fan picked up at the latest<br />

kabuki performance, and, surveying the scene, a wealthy merchant’s wife is transported in a<br />

kago [palanquin] by half-stripped bearers, sweating in the summer heat. As one proverb had<br />

it: 'The person who rides in the kago, the men who bear it; pain in the lower back, pain in the<br />

shoulders.'<br />

The distinctive aizuri technique, which entailed repeated printings in multiple shadings <strong>of</strong><br />

blue, was devised in 1842 to circumvent the draconian governmental sumptuary reforms.<br />

Aside from banning the colourful nishiki-e or ‘brocade’ prints, they also forbad the portrayal<br />

<strong>of</strong> yûjo, geisha and other demimondaines, which explains Eisen’s choice <strong>of</strong> a quotidian street<br />

scene ~ the beauty and iki <strong>of</strong> the women merely hinting at the models’ nightime occupations.

29. Keisai Eisen (1790-1848)<br />

A Courtesan Composing the First Letter <strong>of</strong> the New Year<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1830s<br />

Date [Japanese]: Tempô era<br />

Signature: Hokutei [?]<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Woodblock surimono with karazuri and laquering<br />

Format: Shikishiban<br />

Condition: Some fading and rubbing<br />

Dimensions: 8 x 7 1/4 inches [20 x 18 cm]<br />

Code: BH158<br />

Price [Mounted]: £475<br />

This saitan surimono depicts an elaborately dressed courtesan, writing brush in one hand,<br />

struggling with a winding scroll, on which she has begun to compose her first love letter <strong>of</strong><br />

the New Year. A lacquered suzuribako [‘writing box’] with ink stone and brushes lies at her<br />

feet. The child, oblivious to her travails, has made an origami bird, in imitation <strong>of</strong> those<br />

decorating the kosode hanging at the edge <strong>of</strong> the composition. The kyôka verse is by<br />

Henfukuan.<br />

30. Keisai Eisen (1790-1848)<br />

Courtesan by the Sumida River<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1830<br />

Date [Japanese]: Tempô era<br />

Signature: Eisen-ga<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Sanoya Kihei<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Woodblock print<br />

Format: Single sheet ôban tate-e<br />

Condition: Creasing, wormage, staining and general wear; particularly extensive in<br />

lower right corner<br />

Dimensions: 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £120<br />

Similar in composition to Eisen’s earlier series Tosei Goban Shima (Five Islands <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Present Day), this bijin-ga shows a courtesan at the edge <strong>of</strong> the Sumida-gawa [Sumida<br />

River] in Edo. The overhanging pine is probably the Shubi-no-Matsu [‘The Successful<br />

Conclusion Pine’], one <strong>of</strong> the famous pines <strong>of</strong> Edo, prolifically depicted within Edo meishoe<br />

[‘Pictures <strong>of</strong> Famous Places in Edo’]. It entered the city’s fertile imagination for having a<br />

shape like a dragon, its wide branches spreading out over the river below. Its unusual name<br />

came from its association with returning visitors from the Shin Yoshiwara pleasure district,<br />

located further down the river. In the early hours <strong>of</strong> the morning, it became the custom to<br />

stop by the pine and relate the events <strong>of</strong> the night passed in the ‘green quarters’ - a more<br />

literary group <strong>of</strong> returnees perhaps even devising a suitable poem or epigram on their<br />

romantic adventures. In a layering <strong>of</strong> meaning typical to Ukiyo-e, the matsu imagery may<br />

also relate to the courtesan’s green house: the Matsu-ya being a principal brothel in the<br />

Yoshiwara district.

31. Keisai Eisen (1790-1848)<br />

Fukurokuju with Two Oiran<br />

Date [Western]: 1822 or 1834<br />

Date [Japanese]: Busei/Tempô eras<br />

Signature: Eisen-ga<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Woodblock surimono with gauffrage and detailing in gold<br />

Format: Shikishiban<br />

Condition: Good, some fading<br />

Dimensions: 8 x 9 inches<br />

Code: BH170<br />

Price [Mounted]: £500<br />

This New Year saitan surimono conveys greetings for the Year <strong>of</strong> the Horse [uma], which<br />

is alluded to by the pattern on the right-hand bijin’s kosode and by the miniature hobbyhorse<br />

in her lap. Seated benignly between the two oiran [courtesans] is the god <strong>of</strong> wisdom,<br />

felicitous long life and popularity, Fukurokuji, one <strong>of</strong> the Shichifukujin [Seven Lucky<br />

Gods], who were closely associated with the Shôgatsu [New Year] celebrations. Eisen has<br />

depicted him according to the traditional formula, as a smiling old gentleman, short in<br />

stature with a high forehead (indicating his intelligence) and bushy whiskers, carrying a<br />

hand-scroll tied to a flat fan. Although beloved in Japan, Fukurokuji was originally a<br />

Chinese deity thought to be an embodiment <strong>of</strong> the South Pole stars.<br />

Kyôka verses by, from right to left, Tôkatei Toyû, Senkakutei Hyakunin and Kyôkatei,<br />

surround the figures, elegantly alluding to the New Year.<br />

32. Utagawa Kuniyasu (1794-1832)<br />

Cherry Blossom in the Shin Yoshiwara Pleasure District at the Height <strong>of</strong> its Prosperity<br />

[Tôto Yoshiwara Zensei]<br />

Date [Western]: ca.1830<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Tempô 1<br />

Signature: Kuniyasu-ga<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Tsuru-ya Kiemon<br />

Censor Seal: Kiwame [‘approved’]<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Ôban tate-e triptych<br />

Condition: Reasonable, some evidence <strong>of</strong> block wear<br />

Dimensions: Each sheet 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £500<br />

Kuniyasu Utagawa was born in Edo and trained as a pupil <strong>of</strong> Toyokuni I. He is particularly<br />

known for his surimono and his bijin-ga.<br />

In Kuniyasu’s vibrant print, the Shin Yoshiwara’s most coveted courtesans, surrounded by<br />

admirers, are seen promenading along the famous Naka-no-chô [‘Middle Street’] during<br />

the annual cherry-blossom festival held in the first week <strong>of</strong> the third month [roughly, the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> April]. At the centre <strong>of</strong> the composition, surrounded by a bamboo fence, is<br />

the quarter’s famous cherry tree, depicted in numerous ukiyo-e works and replete with<br />

symbolism relating to the transient nature <strong>of</strong> a courtesan’s life. Indeed, the association <strong>of</strong><br />

the courtesan to the sakura or cherry blossom was such that inscribed on the Ômon [‘great<br />

gateway’] <strong>of</strong> the quarter was the following line: “A Dream <strong>of</strong> Spring-tide when the streets<br />

are full <strong>of</strong> cherry blossom’. An allusion to a Chinese poem immortalizing a womanizing<br />

emperor, it recalled the hundreds <strong>of</strong> verses penned in Edo and Meiji periods comparing the<br />

Yoshiwara beauties to blossom: ‘Cherries <strong>of</strong> the night which bloom luxuriantly,” praises

one, another dramatically describes the ‘Dream <strong>of</strong> Spring, in a town inhabited by beautiful<br />

and voluptuous women to whom their lovers cleave as the commingling blossoms <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cherry bond together’ [See De Becker, 1899, 1971: pp.19-20].<br />

33. Andô Hiroshige (1797-1858)<br />

Tamagawa zutsumi no hana [Cherry Trees in Bloom along the Embankment <strong>of</strong> the Tama<br />

River]<br />

Series: Meisho Edo Hyakkei [A Hundred Famous Views <strong>of</strong> Edo]<br />

Series Number: 42 <strong>of</strong> 120 [inc. Title Page and a replacement print by Hiroshige II]<br />

Date [Western]: 1856<br />

Date [Japanese]: Second Month <strong>of</strong> Ansei 3<br />

Signature: Hiroshige-ga<br />

Publisher’s Seal: Uoya Eikichi<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Nishiki-e woodblock print<br />

Format: Single sheet ôban tate-e<br />

Condition: Good impression; some creasing and rubbing<br />

Dimensions: 15 x 10 inches<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Mounted]: £550<br />

Located in the district <strong>of</strong> Shinjuku, in the western fringes <strong>of</strong> Edo (modern Tôkyô), the<br />

Tamagawa was a twenty-mile-long canal that supplied a major part <strong>of</strong> the city’s population<br />

with drinking water [Uspensky, 1997: p.102]. In the 1850s, the canal banks were studded<br />

with the grand properties <strong>of</strong> daimyô, juxtaposed with inns, shops, eating-houses and various<br />

open air amusements ~ a fluid conflation <strong>of</strong> fixed and floating worlds, which owed<br />

something to the liminal situation <strong>of</strong> this border ward, placed right on the edges <strong>of</strong> the<br />

capital.<br />

To the left <strong>of</strong> the image is the entrance to the mansion <strong>of</strong> the Naito clan, who had originally<br />

owned the entire Shinjuku estate and who inadvertently transformed its fortunes. Having<br />

granted land to six retainers, an equivalent number <strong>of</strong> mansions were built, prompting the<br />

name Rokkenmachi or ‘The Six-House Quarter’ [Ibid]. In the Genroku period (1688-1704),<br />

a group <strong>of</strong> wealthy merchants applied to the landowners for permission to open inns and tea<br />

houses along the canal; a successful bid which transformed the watery neighbourhood into a<br />

little floating world known as Naito-Shinjuku, ‘The New Houses on the Naito Estate.’ It<br />

subsequently developed into one <strong>of</strong> the most popular ‘play’ [asobi] zones in Edo, a<br />

distinction which it retains today. To the right <strong>of</strong> the composition, directly facing the<br />

venerable Naito complex, a group <strong>of</strong> meshimori no onna can be seen, enjoyed the fresh river<br />

breezes on a veranda <strong>of</strong> a tea shop. Representing another layer <strong>of</strong> the mizu-shôbai or ‘water<br />

trade’, meshimori ostensibly acted solely as hostesses or entertainers, in reality, however,<br />

they <strong>of</strong>fered a more approachable and affordable service than their sisters in the licensed<br />

quarters to the east.<br />

34. Utagawa Sadakage (fl. ca. 1820s-1830s)<br />

Courtesan from the Sôrôkan [House <strong>of</strong> the Blue Waves] drinking warm sake<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1820s<br />

Date [Japanese]: Bunsei era<br />

Signature: Gokotei Sadakage-ga<br />

School: Utagawa<br />

Method: Woodblock surimono with gauffrage and detailing in silver.<br />

Format: Shikishiban<br />

Dimensions: 8 x 9 inches<br />

Condition: Excellent with slight colour-fading<br />

Code: BH169<br />

Price [Mounted]: £450

One <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> three small portraits <strong>of</strong> maiko wearing the same furisode kimono, possibly<br />

indicating their allegiance to the same okiya [Cat. No.: 44-47]. These extremely young girls<br />

would have been in the first or second years <strong>of</strong> training, their makeup [note the application<br />

<strong>of</strong> a small circle <strong>of</strong> crimson safflower petal lipstick to the lower lip], attire, and hairstyles all<br />

appropriate to maiko at the outset <strong>of</strong> their careers.<br />

44. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Seated Maiko [Maiko no kaojashin]<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 13<br />

Method: Silver print<br />

Dimensions: 5 1/4 x 3 3/4 inches<br />

Code: AD28<br />

Price [Framed]: £140<br />

45. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Maiko [Maiko no kaojashin]<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 13<br />

Method: Silver print<br />

Dimensions: 5 1/4 x 3 3/4 inches<br />

Code: AD26<br />

Price [Framed]: £140<br />

46. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Geisha [Geisha no kaojashin]<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 13<br />

Method: Silver print<br />

Dimensions: 5 1/4 x 3 3/4 inches<br />

Code: AD35<br />

Price [Framed]: £140<br />

A portrait <strong>of</strong> a young geisha wearing a formal black five-crested tomesode kimono, patterned<br />

with the mon <strong>of</strong> her oki-ya.<br />

47. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> Two Maiko Studying an Album <strong>of</strong> Photographs<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 13<br />

Method: Silver print<br />

Dimensions: 5 1/4 x 3 3/4 inches<br />

Code: AD29<br />

Price [Framed]: £140<br />

Two senior maiko with <strong>of</strong>uku hairstyles. wearing elaborate furisode-style kimono, adopt the<br />

established pose <strong>of</strong> examining a picture book.<br />

From the front, the <strong>of</strong>uku style resembles the wareshinobu coiffure, worn at a maiko’s debut.<br />

At the back, however, the forms diverge, with the kanoko (red spotted silk ribbon, evoking<br />

the markings <strong>of</strong> a young deer) <strong>of</strong> the wareshinobu, being replaced by a tegarami. [a piece <strong>of</strong><br />

silk material] The triangular tegarami, is pinned rather than woven to the bottom <strong>of</strong> the mage<br />

[bun]: the final effect being that <strong>of</strong> a split peach or momoware, the alternative name <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hairstyle. Traditionally, the adoption <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>uku signified the sexual transition <strong>of</strong> the maiko,<br />

either through the ritualized passage <strong>of</strong> the mizuage [loss <strong>of</strong> virginity] or the formal<br />

attentions <strong>of</strong> a patron or danna.

48. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Gaicha de Yokohama<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1875-78<br />

Date [Japanese]: Meiji period<br />

Method: Hand-tinted albumen print<br />

Dimensions: 8 x 5 3/4 inches<br />

Condition: Slight, restored tear in lower centre<br />

Code: AD33<br />

Price [Framed]: £190<br />

One <strong>of</strong> two photographs in the exhibition from a nineteenth-century French album [see also,<br />

Cat. No. 49, below], this depicts a geisha and a maiko, probably sisters from the same okiya,<br />

in a tatami-matted room, re-enacting the preparations for a zashiki [‘a banquet room’; used<br />

as a term for an engagement]. The kneeling geisha is assisting her onêsan in tying her heavy<br />

obi [sash].<br />

During the Edo period, while the form <strong>of</strong> the kimono scarcely changed, the obi appeared in a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> ties and widths, marking trends in fashion and denoting one’s place in both fixed<br />

and floating world hierarchies. It appears that the weave evolved as well, shifting in around<br />

1800, from the pliant fabric evident in prints by, for example, Harunobu (ca.1724-1770), to<br />

the stiff, elaborate, ‘tapestry’ cloth favoured by Kunisada’s bjin [see, for example, Cat. No.:<br />

1-3]. From this point onwards, it came to dominate a woman’s ensemble, so much so that, as<br />

Dalby [1983: p.297] puts it ‘the kimono [became] merely a backdrop for the obi.’<br />

Thus, for the contemporary art historian, the pattern, colour and arrangement <strong>of</strong> the obi is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the key iconographical elements used in determining the societal and pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

positioning <strong>of</strong> its wearer. High-ranking yûjo characteristically tied their obi at the front in the<br />

style <strong>of</strong> married women, to visually suggest that they were ‘married’ to their clients for the<br />

night. The less salubrious explanation being that having the unwieldy obi front-tied,<br />

facilitated expeditious dressing and undressing.<br />

49. Anonymous Photographer<br />

Kamisan de Tokio<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1875-78<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 8-11<br />

Method: Albumen print<br />

Dimensions: 7 3/4 x 5 1/4 inches<br />

Code: AD34<br />

Price [Framed]: £400<br />

An extremely rare portrait study <strong>of</strong> a Okami-san or mistress <strong>of</strong> an ochaya [teahouse],<br />

wearing a formal black five-crested tomesode. Okami-san were retired geisha who, although<br />

still occasionally attending banquets, performing and entertaining clients, presided over the<br />

complex administration <strong>of</strong> the flower and willow world.<br />

In the latter half <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century, the most famous and exclusive hanamachi in<br />

Tôkyô were located in Shimbashi and Asakusa. The former, in particular, being a nerve<br />

centre for the increasingly influential militarists in the Meiji government ~ their celebrations<br />

and parties played out within the teahouses <strong>of</strong> the quarter. Thus, the ostensibly dowdy and<br />

commonplace okamisan depicted in this unusually intimate photograph, would have been<br />

privy to, and in some respects orchestrated, some <strong>of</strong> the most important political gatherings<br />

<strong>of</strong> the age.<br />

50. Anonymous Japanese Photographer<br />

A Study <strong>of</strong> a Maiko in an Garden<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880s<br />

Date [Japanese]: Meiji period<br />

Method: Albumen print

Dimensions: 9 1/4 x 7 1/4 inches<br />

Code: AD32<br />

Price [Framed]: £320<br />

A rare naturalistic outdoor study <strong>of</strong> a senior maiko, or possibly a debuting geisha, wearing<br />

lacquered okubo [high clogs]. Their distinctive sound, resonating throughout the floating<br />

world, entered the Japanese language as the onomatopoeia koppori or pokkuri.<br />

51. Anonymous Photographer, possibly Kusakabe Kimbei (1841-1934)<br />

On Snowing [Geisha in a Two-passenger Jinrikisha]<br />

Date [Western]: ca. 1880-5<br />

Date [Japanese]: Meiji period<br />

Method: Hand-tinted albumen print<br />

Dimensions: 7 3/4 x 10 1/4 inches [Image]<br />

Code: SOX<br />

Price [Framed]: £170<br />

The jinrikisha [lit. man-powered vehicle] or rickshaw first appeared in Tôkyô in 1870. An<br />

invention variously ascribed to Jonathan Goble, an American Baptist missionary, and to<br />

Izumi Yosuke, Suzuki Tokujiro, and Takayama Kosuke, the group <strong>of</strong> enterprising Japanese<br />

townsmen who obtained the first manufacturing license, the jinrikisha quickly replaced the<br />

kago [palanquin] as the transportation <strong>of</strong> choice for the urban masses <strong>of</strong> the Meiji period.<br />

According to a contemporary report in the Shinbun Zasshi newspaper, its rise in popularity<br />

was such that by 1872, only two years after the first passengers were gingerly stepping into<br />

the early prototypes, over 40, 000 were plying their trade in the capital’s streets.<br />

From its inception, it was constructed in one- and two-passenger versions, the latter swiftly<br />

becoming identified with trysts and romantic intimacy, inspiring popular songs such as<br />

Ainori Horokake (‘Beneath a Hood for Two’) and Hoppeta Ottsuke (‘Cheek Pressed to<br />

Cheek’). As such, it became a mainstay <strong>of</strong> early photographer’s studios: here, two young<br />

geisha pose amidst a carefully constructed winter scene.<br />

52. Felice Beato (ca. 1825-ca.1908)<br />

Japonais dans son intérier [Geisha holding an ebony kiseru [pipe], surrounded by the<br />

symbols <strong>of</strong> her art ~ shamisen, koto and tea kettle]<br />

Date [Western]: ca.1880-1883<br />

Date [Japanese]: ca. Meiji 13-16<br />

Method: Hand-tinted albumen silver photograph<br />

Studio Location: Yokohama<br />

Dimensions: 10 x 7 3/4 inches [Image]<br />

Code: AD1<br />

Price [Mounted]: £480<br />

Felice Beato was arguably the most important foreign figure working in the field <strong>of</strong> Japanese<br />

photography in the late nineteenth century. One <strong>of</strong> the originators <strong>of</strong> photojournalism, he<br />

travelled to India in 1857, taking what are retrospectively considered to be the definitive<br />

images <strong>of</strong> the Indian Mutiny, and then to East Asia in 1860, becoming the first Western<br />

photographer to work in China, as he followed and recorded the British army during the<br />

Second Opium War. Previously he had worked as an assistant to James Robertson, whose<br />

body <strong>of</strong> work in the Crimea, to which Beato contributed, is generally defined as the first<br />

distinct example <strong>of</strong> objective war photojournalism.<br />

Beato was probably born in Corfu, then a Venetian territory, but at some point he and his<br />

brother Antonio (or Antoine) Beato (ca.1830-ca.1903), both became British citizens. This<br />

was a period when Britain welcomed political exiles and many Italian nationalists, such as<br />

the Rossetti family, were living and working in London. Antonio Beato was also a keen<br />

photographer and the two brothers worked together on a number <strong>of</strong> occasions, signing their<br />

collaborative works Felice Antonio Beato; later problematizing the identification <strong>of</strong>

photographs taken at the same time in different locations. For the majority <strong>of</strong> his working<br />

life, however, Antonio resided in Egypt, running a flourishing studio specializing in the<br />

photography <strong>of</strong> antiquities.<br />

Beato arrived in Japan in around 1862, living in Yokohama from 1863 to 1884. He initially<br />

joined Charles Wirgman, an ex-patriot since 1861; the two forming a partnership entitled<br />

‘Beato & Wirgman, Artists and Photographers’ during the years 1864–1867. A trained<br />

watercolourist, Wirgman developed a technique <strong>of</strong> adding colour washes to his albumen<br />

prints; a technical advance which greatly contributed to the popularity <strong>of</strong> the partners’<br />

oeuvre, particularly amongst Occidental collectors already enamoured <strong>of</strong> the sophisticated<br />

colouring present in woodblock prints. Before long, the studio was inundated with work<br />

and, to satisfy demand, Beato began to employ Japanese Ukiyo-e colourists. Organized as a<br />

production line, they could complete 20 or 30 high-quality prints a day, a number which was<br />

quickly absorbed by the gaijin travellers, merchants and who flocked to Beato’s emporium.<br />

Beato's Japanese photographs include bijin portraits, genre works, landscapes, cityscapes<br />

and, consciously recalling Hiroshige and Hokusai, a number <strong>of</strong> meisho-e documenting the<br />

scenery and sites along the Tôkaidô.<br />

Despite his large output, Beato's images are remarkable not only for their quality, but for<br />

their rarity as photographic views <strong>of</strong> a lost Japan at the brink <strong>of</strong> cataclysmic change.<br />

53. Felice Beato (ca. 1825-ca.1908)<br />

Portrait <strong>of</strong> a Geisha<br />

Date [Western]: 1863<br />