BOGOTA - Le Corbusier en Bogotá

BOGOTA - Le Corbusier en Bogotá

BOGOTA - Le Corbusier en Bogotá

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

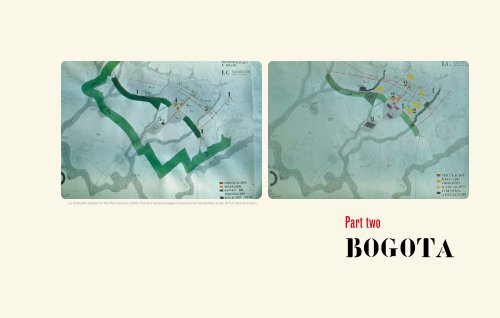

<strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>, project for the Plan Director (1950): First and second stages of execution at metropolitan scale. © FLC Archivo Pizano.<br />

Part two<br />

<strong>BOGOTA</strong>

Bogota, 1940-1950: Towards modernization<br />

Alberto Saldarriaga Roa<br />

The city of Bogota transformed itself radically throughout the<br />

20th c<strong>en</strong>tury. At the beginning of the c<strong>en</strong>tury, it still conserved<br />

its colonial appearance and was just initiating the route towards<br />

the improvem<strong>en</strong>t of the conditions of its public services,<br />

of the collective transportation, the communications,<br />

and in g<strong>en</strong>eral the quality of life of at least one sector of his<br />

population. An embryonic idea of modernization was pres<strong>en</strong>t<br />

in those attempts. It advanced gradually and acquired a special<br />

str<strong>en</strong>gth towards 1930, wh<strong>en</strong> the national governm<strong>en</strong>t,<br />

th<strong>en</strong> in the hands of the Liberal Party, adopted it as an official<br />

purpose. In the following fifte<strong>en</strong> years the modernizing spirit<br />

attempted to take root in diverse sectors of the national life:<br />

60 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

Office of the Regulator Plan (OPR), Five-Year<br />

Plan, street-wid<strong>en</strong>ing, Av<strong>en</strong>ida<br />

Norte Quito Sur, and the placem<strong>en</strong>t of<br />

Paloquemao market plaza, 1951.<br />

© A-D Archivo de <strong>Bogotá</strong> 201-001-23<br />

public administration, education, health, and culture, among<br />

others. The small intellectual and artistic groups of the time<br />

inclined towards the leftist ideas and watched with somewhat<br />

delayed interest the proposals of the European and North<br />

American vanguards. The private sector, impelled by the advances<br />

of the capitalism, found in the bank, industry, commerce,<br />

and <strong>en</strong>tertainm<strong>en</strong>t, horizons of modernization, and<br />

approached them. Therefore, a bicephalous conception of<br />

modernization and progress became established, one liberalizing,<br />

the other conservative. The country’s turn towards the<br />

conservatism after 1945 discarded the socializing cont<strong>en</strong>t<br />

of the previous governm<strong>en</strong>ts and wanted to str<strong>en</strong>gth<strong>en</strong> the<br />

modernizing approach of the private world, visible, among<br />

other things, in the works of <strong>en</strong>gineering and architecture.<br />

Betwe<strong>en</strong> 1940 and 1950, Bogota had a considerable<br />

increase of population. The 1938 c<strong>en</strong>sus gave an approximated<br />

number of 330,000 inhabitants; in 1951 it registered<br />

715,000. The urban plans of that period show a city of an elongated<br />

shape, from south to north, on the side of the eastern<br />

mountains and still distant from the Río <strong>Bogotá</strong>. The growth of<br />

the city during this decade is manifested in its acc<strong>en</strong>tuated<br />

prolongation towards the north <strong>en</strong>d, a minor stretch to the<br />

south <strong>en</strong>d, and some urbanized conc<strong>en</strong>trations on the western<br />

edge. The streetcars’ routes and some of the important<br />

roads, like the 7 th Carrera, Caracas Av<strong>en</strong>ue, and the Av<strong>en</strong>ue<br />

of the Americas, connected the urban fabric and propitiated<br />

their developm<strong>en</strong>t. 1<br />

Bogota’s urban landscape was, according to photographs<br />

of the period, one of a medium size city of low height, surrounded<br />

by the untamed nature of eastern mountains and the<br />

broad ext<strong>en</strong>sion of the high plateau. The tallest constructions<br />

were located in the banking area of the Jiménez de Quesada<br />

Av<strong>en</strong>ue and the gre<strong>en</strong> spaces of C<strong>en</strong>t<strong>en</strong>ary Park, Indep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>ce<br />

Park and—greatest of all—the National Park, stood out<br />

in this landscape. In the resid<strong>en</strong>tial neighborhoods built after<br />

1930 there was the developm<strong>en</strong>t of a domestic architecture,<br />

the “English style”, that has characterized the north sector of<br />

the city since th<strong>en</strong>. In publications of the time it is possible to<br />

appreciate differ<strong>en</strong>t images of this landscape. 2 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong><br />

visited Bogota before and after the disturbances of the 9th<br />

of April of 1948. The city that he visited in 1951 was not the<br />

same than the one he got to know in his first stay; the country<br />

was not the same either. The political atmosphere, rarefied

after the murder of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, should have manifested<br />

itself, one way or another, in the reception of its work.<br />

The signs of destruction in Bogota’s c<strong>en</strong>ter were too visible to<br />

be ignored. Did <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> perceive those changes? Did<br />

they influ<strong>en</strong>ce the final version of the plan?<br />

The visualized modernization<br />

The evid<strong>en</strong>t signs of the modernization of the city betwe<strong>en</strong><br />

1940 and 1950 were not abundant, but some of them were<br />

quite significant. The celebration, in 1938, of the fourth c<strong>en</strong>t<strong>en</strong>ary<br />

of the foundation of the city had already motivated some<br />

important advances, one of them putting into operation the<br />

aqueduct of Vitelma, the first really modern aqueduct in the<br />

history of the city. The works inaugurated in that year included<br />

schools, parks, sport facilities, some housing neighborhoods<br />

for workers and employees, and a quite complete treatm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

plan of the eastern edge of the c<strong>en</strong>ter, planned by Karl Brunner,<br />

who led practically all the realized works.<br />

With the University City, outlined by <strong>Le</strong>opoldo Rother and<br />

Fritz Kars<strong>en</strong>, an integral plan of urban and architectural developm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

of a large area of land located in the western periphery<br />

of the city, the first step was tak<strong>en</strong> toward the modern<br />

planning of Bogota. In the plan are evid<strong>en</strong>t certain echoes of<br />

the preceding academicism, especially the symmetrical disposition<br />

of the roadways and the buildings. Actually, these<br />

were released as indep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>t units and in each of the first<br />

ones, without giving up the principles of symmetry, an analogous<br />

but not id<strong>en</strong>tical formal treatm<strong>en</strong>t was applied; Rother<br />

explored some of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s architectural principles in<br />

the <strong>en</strong>trance buildings and in the houses for professors and<br />

projected later, in 1945, the printing press building, an original<br />

and interesting work with a formal language completely<br />

dissimilar to his first works. The University City was a special<br />

urban planning exercise completely differ<strong>en</strong>t from the developm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

model applied to the rest of Bogota, based on building<br />

“urbanizations” or “neighborhoods” by private businessm<strong>en</strong>,<br />

consisting of the bounding of streets, blocks and lots,<br />

with the required intervals for parks and some communitar-<br />

Photograph by Daniel Rodríguez of English-style houses in the Merced neighborhood, from M<strong>en</strong>doza de Riaño, Consuelo, <strong>Bogotá</strong> the City, Ediciones Gamma<br />

– Consuelo M<strong>en</strong>doza Ediciones, <strong>Bogotá</strong>, 2006.<br />

Bogota, 1940-1950: Towards modernization | Alberto Saldarriaga Roa<br />

61

ian services. Two municipal public institutions, the Instituto<br />

de Acción Social (Institute of Social Action) and the Caja de<br />

la Vivi<strong>en</strong>da Popular (Bank of Popular Housing) and another<br />

institution of national order, the Banco C<strong>en</strong>tral Hipotecario<br />

(C<strong>en</strong>tral Hypothecary Bank) carried out several small housing<br />

developm<strong>en</strong>ts for workers and employees. Among these<br />

neighborhoods, the Model of the North, designed by Karl<br />

Brunner, excels. In the Model of the North are applied some<br />

norms derived from the Decree 380 of 1942, which formulated<br />

and regulated the proposal of Barrios Populares Modelo<br />

(Popular Neighborhoods Model), a Colombian interpretation<br />

of the “neighborhood unit” followers of the ideas of the city<br />

planners Clar<strong>en</strong>ce Perry and Clar<strong>en</strong>ce Stein and already applied<br />

in several American cities.<br />

The Instituto de Crédito Territorial (Institute of Territorial<br />

Credit) advanced the developm<strong>en</strong>t and updating of that<br />

proposal and, in the neighborhood unit of Muzú, in 1948,<br />

applied a new city-planning model, the one of superblocks,<br />

interconnected externally by two unique vehicular roadways<br />

and in their interior by a network of pedestrian footpaths<br />

integrated to the op<strong>en</strong> gre<strong>en</strong> areas. A few years later, in the<br />

neighborhood unit Quiroga, after the visits of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> and<br />

Josep Lluís Sert, the model was perfected in some aspects,<br />

before being abandoned almost completely. In both works, the<br />

institute tried prefabrication systems using reinforced concrete<br />

pieces, in a first attempt of industrialization of the construction<br />

process. In another field of work, some incipi<strong>en</strong>t architecture<br />

and <strong>en</strong>gineering companies quickly adopted the functional and<br />

technical principles of the international architecture and were<br />

in charge of realizing some commissions of some importance.<br />

Standouts among them are the company Cuéllar Serrano<br />

Gómez, established in 1939, which projected and constructed<br />

two significant buildings towards 1948: the Hospital of San<br />

Juan de Dios and the headquarters for the Caja Colombiana<br />

de Ahorros. A novel system of construction for concrete slab<br />

floors, the “reticular celulado”, (waffle slab) designed by Italian<br />

<strong>en</strong>gineer Doménico Parma Marré, was applied in the first<br />

building. A steel structure imported from the United States was<br />

used in the second, the highest building of the city at that time,<br />

which accelerated its execution remarkably.<br />

62 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

<strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> and the modernizing spirit<br />

<strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s first visit was not fortuitous: he was invited expressly<br />

in response to his offer to elaborate the urban plan of<br />

the city. <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> was recognized as a great master in<br />

the university and professional field, but he was little known<br />

in political and economic circles. His visit, aside from exciting<br />

the architecture stud<strong>en</strong>ts of the Universidad Nacional, was<br />

ori<strong>en</strong>ted to the motivation of the governm<strong>en</strong>tal and private<br />

sectors towards a radical modernization of the city modeled<br />

in agreem<strong>en</strong>t with his ideas.<br />

Three urban plans preceded the first visit of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>.<br />

One of them was the roadway and zoning plan, elaborated in<br />

1944 by <strong>en</strong>gineer Alfredo Bateman during the mayoralty of<br />

Jorge Soto del Corral and known by the name Soto-Bateman.<br />

The Colombian Society of Architects formulated, the following<br />

year, a counter proposal that was not adopted, just like the<br />

roadway proposal published by Carlos Martinez Jiménez in<br />

Proa magazine in 1946. The three plans were modern in their<br />

own ways, but they did not respond strictly to a citywide project.<br />

It is not very clear whether some of the ideas contained in<br />

these plans influ<strong>en</strong>ced <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s proposal to any ext<strong>en</strong>t.<br />

The modern notion of the “plan” had spread as much<br />

from the academy as from the professional architects’ guild.<br />

The study of urbanism had be<strong>en</strong> established in the School<br />

of Architecture of the Universidad Nacional since 1938. Its<br />

main impellers were Karl Brunner, Carlos Martinez Jiménez,<br />

and Herbert Ritter. The latter two of these adhered quickly<br />

to the ideas of modern urbanism and ev<strong>en</strong>tually distanced<br />

themselves from Brunner’s proposals, which were described<br />

as “academic”. It is significant that the magazine Proa—<br />

founded in 1946 by Martinez Jiménez, along with Jorge<br />

Arango Sanín and Manuel de V<strong>en</strong>goechea, and dedicated<br />

to the subjects of “Urbanism, Architecture and Industry”—<br />

included in its first issue an article signed by the architects’<br />

promotion of 1945, titled “For Bogota to be a modern city”,<br />

and that in the second issue, from September of that year,<br />

Jose de Recas<strong>en</strong>s would write a article titled “The other <strong>Corbusier</strong>”,<br />

in which he dealt with the painting and sculpture of<br />

the Swiss architect. Ev<strong>en</strong> more interesting is the third issue<br />

of Proa, dedicated to the subject “Bogota can be a modern<br />

city”, conc<strong>en</strong>trated on the “re-urbanization of the c<strong>en</strong>tral<br />

market place and of the 16 neighboring blocks”, an ambitious<br />

project of urban r<strong>en</strong>ovation that covered from 7 th Street,<br />

in the south, to 11 th Street, in the north, and from the 9th<br />

Carrera, to the east, until the 12 th Carrera, in the west. The<br />

project was a set of repetitive high buildings, an ext<strong>en</strong>sion<br />

block, resting on low platforms, with interior gre<strong>en</strong> spaces<br />

and a large park. 3<br />

From the proposal published by Proa it can be deduced<br />

that for its authors an appreciable portion of the historical<br />

c<strong>en</strong>ter of Bogota was susceptible to being demolished, becoming<br />

a fragm<strong>en</strong>t of a modern city. There was no m<strong>en</strong>tion of<br />

an interest in its patrimonial value. That attitude was characteristic<br />

of the modern approach regarding the transformation<br />

of old sectors that the same <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> had exemplified<br />

with his famous Plan Voisin for Paris. The <strong>en</strong>counter betwe<strong>en</strong><br />

the Swiss architect and his young Colombian colleagues had,<br />

th<strong>en</strong>, affinities that facilitated the much more radical proposal<br />

of the Swiss architect for the future civic c<strong>en</strong>ter of Bogota.<br />

Bogota post-<strong>Corbusier</strong><br />

The set of factors previously described allows us to understand<br />

that at the time of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s first visit to Bogota<br />

there already existed, in differ<strong>en</strong>t political, academic, cultural,<br />

and business spheres, a favorable attitude towards modernization.<br />

It is significant to acc<strong>en</strong>tuate the importance of the<br />

facts that happ<strong>en</strong>ed betwe<strong>en</strong> 1947 and 1950, which affected<br />

not only the city but also the country. In the following decade,<br />

Bogota’s population increased explosively and in 1964 it<br />

reached 1,700,000 inhabitants, more than double the population<br />

in 1951. A good part of the population growth was due<br />

to the massive arrival of immigrants expelled from the rural<br />

areas by the political viol<strong>en</strong>ce that reached levels of cruelty<br />

never before known in Colombia.<br />

During the dictatorship of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (1953-<br />

1957), two works of great urban-planning impact were completed<br />

in the east-west axis: the Official Administrative C<strong>en</strong>ter

and the El Dorado airport. The north freeway was built as an<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sion of Caracas Av<strong>en</strong>ue. These works were not anticipated<br />

in the definitive version of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s plan, translated<br />

to practical terms by Wi<strong>en</strong>er and Sert. The change of place<br />

of the civic c<strong>en</strong>ter, from the c<strong>en</strong>ter to the periphery of the city,<br />

was one of the signs of the abandonm<strong>en</strong>t of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s<br />

proposal. The plan was retak<strong>en</strong> and modified some years later<br />

by the architects of the Planning Office of the city. After the dictatorship,<br />

the planning of the city acquired another course and<br />

a cascade of plans began that has concluded partially with the<br />

actual Plan of Territorial Ordering. The ghost of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong><br />

has be<strong>en</strong> pres<strong>en</strong>t in all of them.<br />

Alberto Saldarriaga Roa. Architect from the Faculty of Arts and the Universidad<br />

Nacional de Colombia (1965). Specialized in Housing and Planning<br />

from the C<strong>en</strong>tro Iberoamericano de Vivi<strong>en</strong>da in Bogota. Completed<br />

courses of Urban Planning at the University of Michigan (USA). He is the<br />

author of several publications, among them: Habitabilidad (1976), Arquitectura<br />

y Cultura <strong>en</strong> Colombia y Arquitectura para todos los días, (1986)<br />

Arquitectura Popular <strong>en</strong> Colombia: Her<strong>en</strong>cias y Tradiciones, with Lor<strong>en</strong>zo<br />

Fonseca (1988); Arquitectura fin de siglo, Apr<strong>en</strong>der Arquitectura and the<br />

CD-Rom <strong>Bogotá</strong> CD (1992); <strong>Bogotá</strong> siglo XX. Urbanismo, arquitectura y<br />

vida urbana (2000). In 2005, he was recognized with the America prize in<br />

the category of Theory in the Ninth Seminary of Latin American Architecture<br />

gathered in Mexico. He has won several Bi<strong>en</strong>nials in Colombia and<br />

Ecuador. He has be<strong>en</strong> professor at Universidad de los Andes and the<br />

Universidad Nacional de Colombia and he was the academic coordinator<br />

of the program of Maestría <strong>en</strong> Historia y Teoría del Arte y la Arquitectura<br />

de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia (1989-2005). At the mom<strong>en</strong>t he<br />

is the dean of the Facultad de Ci<strong>en</strong>cias Humanas, Arte y Diseños of Jorge<br />

Tadeo Lozano University<br />

1 Marcela Cuéllar y Germán Mejía Pavony, Atlas histórico de <strong>Bogotá</strong>. Cartografía,<br />

1791-2007 (Alcaldía Mayor de <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Planeta, 2007).<br />

2 Guillermo Hernández de Alba, Álbum de <strong>Bogotá</strong>, 1938, Sociedad de Mejoras<br />

y Ornato de <strong>Bogotá</strong> (<strong>Bogotá</strong>: Litografía Colombia, 1948).<br />

3 The authors of the proposal were Luz Amorocho, Enrique García, José J.<br />

Angulo and Carlos Martínez.<br />

Luz Amorocho, Enrique García, José J. Angulo and Carlos Martínez, proposal for the reurbanization of the c<strong>en</strong>tral market plazas and the surrounding 16 blocks,<br />

published in Proa No. 3: “<strong>Bogotá</strong> can be a Modern City.” © Proa<br />

Bogota, 1940-1950: Towards modernization | Alberto Saldarriaga Roa<br />

63

Notes for a context on the Pilot Plan and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota<br />

Hernando Vargas Caicedo<br />

But mainly, what is needed is a change of m<strong>en</strong>tal attitude.<br />

Once we have be<strong>en</strong> convinced truly that the time of the cities<br />

is a reality and that they are going to grow, that the majority<br />

of us are going to pass the majority of our lives in the cities,<br />

that a high d<strong>en</strong>sity is conv<strong>en</strong>i<strong>en</strong>t economically and that is<br />

possible without congestion, that the character and the distinction<br />

of a city affects our well-being and that, as in many<br />

European cities, wh<strong>en</strong> we built it must be in a lasting way<br />

and that it adjusts to a harmonic pattern and not something<br />

improvised that it has to be tak<strong>en</strong> down in a few years. If we<br />

are able to carry out this m<strong>en</strong>tal revolution, th<strong>en</strong> it will follow,<br />

on its own, the revolution of our physical <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t, we will<br />

be able to guide our destinies in a conci<strong>en</strong>tious and rational<br />

way, or will have to remain in the hands of blind forces. This<br />

is, in ess<strong>en</strong>ce, the question. 1<br />

This text sets out to suggest and order elem<strong>en</strong>ts of refer<strong>en</strong>ce<br />

infrequ<strong>en</strong>tly noticed in the increasing literature that has<br />

come out in the rec<strong>en</strong>t years on the g<strong>en</strong>esis of the Pilot Plan<br />

and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota and the mom<strong>en</strong>t in which<br />

they unfolded. It is presumed that these processes were the<br />

result of ext<strong>en</strong>sive incubations and confrontations of differ<strong>en</strong>t<br />

natures. Among differ<strong>en</strong>t natures, it will argue that the awar<strong>en</strong>ess<br />

of the needs of and options for urban modernization<br />

drove the exploration of differ<strong>en</strong>t options and models with<br />

diverse efforts of adaptation. It will finish with some lessons<br />

possibly learned.<br />

64 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

Urban evolution until World War II<br />

In the slow 19th c<strong>en</strong>tury, the only plan of ext<strong>en</strong>sion for Bogota<br />

that is remembered is the one by the g<strong>en</strong>eral Mosquera, in<br />

the days of the speculative euphoria sparked by the dis<strong>en</strong>tailm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

of dead hands’ property. 2 The major Colombian cities<br />

had begun to show signs of overcrowding and deterioration<br />

at the <strong>en</strong>d of the 19th c<strong>en</strong>tury, wh<strong>en</strong> the first series of industrialization<br />

and improvem<strong>en</strong>t announced new molds and problems.<br />

3 Already, the street cars had indicated the impact that<br />

they could have on urban size and forms, as in the case of<br />

Chicago or Bu<strong>en</strong>os Aires. 4 Bogota did not have, as São Paulo<br />

did, the push of great promoters like those of the Companhia<br />

City, that advanced the <strong>en</strong>ormous urbanizations of Jardim<br />

America from 1912. 5 The first zones for working districts;<br />

the promotion of urbanization in ext<strong>en</strong>sions; the appearance<br />

and ext<strong>en</strong>sion of new <strong>en</strong>ergy, aqueduct, telephone, and public<br />

transportation networks, expressed how the population<br />

growth and the specialization of the urban c<strong>en</strong>ters during the<br />

republican period demanded more space and better standards.<br />

On the other hand, there appeared normative indications<br />

on building control, efforts to make technical surveys,<br />

hygi<strong>en</strong>e campaigns promoting gre<strong>en</strong> spaces and cleanings.<br />

With the arrival of the railroads in Colombian cities (Barranquilla,<br />

1871; Bogota, 1889; Medellin, 1914; Cali, 1915),<br />

the problem int<strong>en</strong>sified. In the middle of a g<strong>en</strong>eration of real<br />

estate promoters like Nemesio Camacho or José María Sierra,<br />

who had multiple businesses and were of rural origin, a<br />

figure like Ricardo Olano typified the preoccupation of the<br />

impresario with undertaking urban ext<strong>en</strong>sions within a consciously<br />

organized framework of future city, drawing from<br />

international experi<strong>en</strong>ce. Olano, after att<strong>en</strong>ding the international<br />

confer<strong>en</strong>ce of dwelling and urbanism in Paris in 1928,<br />

donated his books on the subject to the School of Mines, on<br />

the condition that a course be offered on the subject. 6<br />

After Medellin, Bogota and Cali joined the movem<strong>en</strong>t of<br />

adhesion to ext<strong>en</strong>sion plans, wh<strong>en</strong> the resources of the economic<br />

expansion of the tw<strong>en</strong>ties— with public money received<br />

from the indemnification of Panama and local and international<br />

banking recourses—allowed for diverse improvem<strong>en</strong>ts in<br />

aqueducts, market places, and the creation of schools and<br />

roads. It was also the time in which foreign standards for landscapes<br />

and paving in concrete were noticed, like those of El<br />

Prado or urbanizations like the Mutual b<strong>en</strong>efit society. 7<br />

Before the city planners came, it was the time of architect<strong>en</strong>gineers<br />

like Enrique Uribe Ramírez, who led improvem<strong>en</strong>t<br />

proposals on the contin<strong>en</strong>t. We should not forget that the <strong>en</strong>gineer<br />

of Ponts et Chaussées, Maurice Rotival, was hired for<br />

the plan for Caracas since the <strong>en</strong>d of the gomecismo. 8 The<br />

pres<strong>en</strong>ce of international founds, grew to support urban infrastructure<br />

works, as weak local financial resources could not<br />

keep up with the rate of industrial growth and urbanization<br />

that took place in the 1930s... On rare occasions, as in Barranquilla,<br />

this resulted in advanced models for the managem<strong>en</strong>t<br />

of municipal services. For its part, the problem of housing<br />

for workers, which had be<strong>en</strong> se<strong>en</strong> by early legislators as<br />

a problem of public budgets and lobby groups, now drew<br />

att<strong>en</strong>tion from new public, local and national institutions.<br />

In the shield of the respice polum of Marco Fidel Suárez,<br />

it is significant that the presid<strong>en</strong>t Olaya Herrera (1930-1934),<br />

former ambassador to the United States, would determine<br />

that Bogota should have an urban plan which would follow the

code of urbanism from the prestigious Bartholomew, pioneer<br />

of the new profession in North America. And that, in circumstances<br />

that are still murky, with his important responsibilities<br />

in commissions in Chile, Karl Brunner arrived at Bogota to<br />

direct the significant Planning Office in 1933. In a very short<br />

time, Brunner, who educated the Council with his exhibition<br />

in the Teatro Colón in 1937, created unpreced<strong>en</strong>ted criteria,<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sions, districts, and public spaces, made possible with<br />

national, municipal and private initiatives. The urbanism of<br />

Brunner, under the epigraph of Mumford, was a form of high<br />

culture, a s<strong>en</strong>se of civic, political, aesthetic, and technical<br />

organization. The Austrian professor combined European,<br />

North American, and ev<strong>en</strong> South American ideas on the best<br />

possible city, in an expert effort that aspired to synthesize<br />

them all in the Regulatory Plan.<br />

The Bogota that Brunner advised in the thirties clearly knew<br />

weaknesses. It was the imm<strong>en</strong>se village without municipal<br />

services. Aside from the sectors of piedemonte that demanded<br />

cleanings, there was flood congestion by the c<strong>en</strong>ter-north<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sion, very old public buildings in inconv<strong>en</strong>i<strong>en</strong>t places,<br />

a lack of parks, blocked roadways, no deliberate direction of<br />

growth, and disorderly industry scattered throughout. What<br />

one hoped that the capital had in 1950, after the blessing of<br />

works like those that the IV C<strong>en</strong>t<strong>en</strong>ary of 1938, was a series of<br />

interconnected parks; new locations for three main markets;<br />

bus and train stations; defined working districts; organized<br />

factories, workshops, and deposits. Brunner noticed that the<br />

hills were occupied illegally, and saw that businesses had to<br />

be kept out of the hills and that pathways and linear parks<br />

were necessary for their conservation. To sum up, Brunner’s<br />

was an inward-looking operation on the existing city, with new<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sions, arduous surgeries, relocated connections that<br />

<strong>en</strong>countered the impact that, in its own words, had the same<br />

urban valuation. 9 It is necessary to remember that Brunner<br />

and Humeres already had developed a plan in Santiago that<br />

was considered a segregator of popular districts, aestheticizing<br />

the public buildings and ing<strong>en</strong>uous in its demographic<br />

projections, although their insist<strong>en</strong>ce in the maint<strong>en</strong>ance of<br />

parks is recognized. 10<br />

Brunner had expanded his actions to Cali, where he was<br />

in charge of urbanizations like Versailles, Miraflores, and<br />

Santa Isabel; the Regulatory Plan of the Future City was commissioned<br />

in 1944 and it faced the pressures of developers<br />

who were resisting the halt of new lic<strong>en</strong>ses while they were<br />

finalizing the plan that would be finally adopted by the city, in<br />

August of 1947. 11<br />

The capital was also on the minds of politicians, doctors,<br />

and <strong>en</strong>gineers. Despite the high turnover of mayors, a few,<br />

like Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, Germán Zea and Carlos Sanz de<br />

Santamaría, <strong>en</strong>thusiastic about sewage systems, contributed<br />

suffici<strong>en</strong>t mandates to propose and realize improvem<strong>en</strong>ts<br />

before developers like Mazuera Villegas, Trujillo Gómez,<br />

and Salazar Gómez took office. 12 Behind Medellin, that had<br />

a leftover hydroelectric network from 1932, Bogota dreamed<br />

about a modern aqueduct, which came to fruition in Vitelma.<br />

In spite of this, it suffered, put under the yoke of the quick<br />

urbanization of the 1930s and 40s, with chronic rationing until<br />

the <strong>en</strong>d of the following decade, wh<strong>en</strong> it was able to fill with<br />

Bogota river’s supply.<br />

We must remember that the Pearson house made the first<br />

survey for the modern project of an aqueduct in 1907. Despite<br />

this, ev<strong>en</strong> in 1954 there were complaints that the capital<br />

did not know the networks that it had and that its sewage<br />

system was hardly of a third of the indicated urban area in the<br />

Pilot Plan, with serious defici<strong>en</strong>cies in the c<strong>en</strong>tral areas and<br />

impure tr<strong>en</strong>ches. From 1940, with the support of the international<br />

guru in geotechnics, professor Arthur Casagrande of<br />

Harvard, there appeared in Vitelma’s periphery—in the Muña,<br />

Neusa and Sisga—projects that provided water and <strong>en</strong>ergy<br />

to a city that resisted paying for them. 13<br />

The industrialization had sped up in the 1930s with the<br />

stimulus from the state and it continued in the 40s with the<br />

opportunities that the war offered manufacturers. The commerce<br />

had barely be<strong>en</strong> modernized and without new space<br />

had dispersed linearly. The markets remained in the c<strong>en</strong>ter<br />

of the city, with impact unanimously indicated in all the proposals<br />

of improvem<strong>en</strong>t. In those days, the new campus of<br />

the Universidad Nacional and the stadium were islands of<br />

modernity.<br />

From the war to the Pilot Plan<br />

With the convulsions that the international conflict caused in<br />

the economy, business had begun to organize in the ANDI<br />

and F<strong>en</strong>alco, and the labor and social legislation gradually<br />

recognized the new features in the middle of the political controversy.<br />

The rural country announced its conversion to the<br />

Colombia of cities of the second half of the c<strong>en</strong>tury and the<br />

state assumed tasks in industry, housing, health, tourism,<br />

transportation, and education, that compromised important<br />

economic and human resources in a successive series of<br />

initiatives. The state desired to demonstrate its str<strong>en</strong>gth by<br />

pres<strong>en</strong>ting the results of its modernization, particularly in the<br />

showcase of the capital.<br />

Hernando Vargas Rubiano was elected presid<strong>en</strong>t of the<br />

SCA at the beginning of 1947. He was a member of the first<br />

group of stud<strong>en</strong>ts to graduate from the Faculty of Architecture<br />

at the Universidad Nacional in 1941, a group of professionals<br />

who wanted to be increasingly visible and influ<strong>en</strong>tial, especially<br />

after their criticism of the Soto-Bateman plan in 1943. 14<br />

Wh<strong>en</strong> he saw in the newspaper El Tiempo the news of <strong>Le</strong><br />

<strong>Corbusier</strong>’s visit with Rockefeller and Eduardo Zuleta Angel<br />

to the site of the United Nations project in New York, Rubiano<br />

had the idea that the SCA convince the national governm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

and the mayor of the city to have the architect and city planner<br />

visit Bogota, dictate confer<strong>en</strong>ces, and be put in charge<br />

of advising on urban developm<strong>en</strong>t. (Brunner’s star, by th<strong>en</strong>,<br />

had begun to exhaust itself.) Giv<strong>en</strong> the fri<strong>en</strong>dship of Zuleta<br />

and <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>, it was easy to get the interest the European<br />

architect, although it was very unusual that th<strong>en</strong>-mayor<br />

Mazuera, who would go on to great accomplishm<strong>en</strong>ts in governm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

and real estate developm<strong>en</strong>t, failed to recognize<br />

him at all. With the company of Gabriel Serrano and Gabriel<br />

Largacha, Vargas Rubiano started up this contact, which culminated<br />

in the mythological first visit of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>. Vargas<br />

Rubiano was abs<strong>en</strong>t because a familiar duel, in the tribute to<br />

Corbu in the Granada Hotel, Largacha read the speech of<br />

the presid<strong>en</strong>t of the SCA in which he praised the architecture<br />

and the urbanism of the visitor and declared him a honorary<br />

member of it. “Master of his g<strong>en</strong>eration”, he was called; his<br />

Notes for a context on the Pilot Plan and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota | Hernando Vargas Caicedo<br />

65

Karl Brunner, plan designed by the research team led by Fernando Cortés Larream<strong>en</strong>dy based on the plan from 1941 that includes the housing developm<strong>en</strong>t and other projects<br />

for Bogota, published in the exposition catalogue, “Karl Brunner – Arquitecto Urbanista, 1887-1960”, at the Bogota Museum of Modern Art, May of 1989.<br />

66 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

Housing developm<strong>en</strong>ts:<br />

1. Palermo, 1934<br />

2. Prelimary plan for El Campin, 1934<br />

3. El Retiro, 1939<br />

4. Medina, 1935<br />

5. Workers’ Neighborhood, Social and Sports C<strong>en</strong>ter, 1935<br />

6. Project for El Campin<br />

7. San Luis, 1936<br />

8. El Bosque Izquierdo, 1936<br />

9. El C<strong>en</strong>t<strong>en</strong>ario neighborhood, 1938<br />

10. Ciudad Del Empleado (The Employees’ City), 1942<br />

11. Satellite City, 1942<br />

Street expansions and road plans<br />

12. Study of the Ensanche Sur, 1934<br />

13. Study of the Ensanche Occid<strong>en</strong>tal, 1934-35<br />

14. Study of the Ensanche de la Calle Real, 1935<br />

15. Study of construction of the Av<strong>en</strong>ida C<strong>en</strong>tral, 1935<br />

16. Road plan for Bogota, 1936-37<br />

17. Road op<strong>en</strong>ing, 1934<br />

18. Regulator plan and street-wid<strong>en</strong>ing in Bogota<br />

19. Regulation of the Av<strong>en</strong>ida Caracas<br />

20. Regulation of the Av<strong>en</strong>ida Jiménez<br />

Other constructions:<br />

21. Media Torta cultural c<strong>en</strong>ter<br />

22. Gard<strong>en</strong>s at the Escuela Bellavista<br />

23. El Campin stadium<br />

24. Humboldt Monum<strong>en</strong>t<br />

25. Emerg<strong>en</strong>cy Clinic<br />

26. “Daytime” Hotel project (subterranean)<br />

27. Lookout Terrace at the Paseo Bolívar<br />

28. Ext<strong>en</strong>sion of 26 th St.<br />

29. Tranvia stops<br />

30. Kiosks for the Paseo Bolívar<br />

Parks<br />

31. Paseo Bolivar Park<br />

32. Park on 13 th St. and 26 th Ave.<br />

33. Plaza de Nariño<br />

34. Santander Park<br />

35. Santa Sofia Park<br />

36. San Martin Park<br />

37. San Diego Park<br />

38. El Salitre Forestal Park<br />

39. Panamerican Forest<br />

40. San Fernando Park<br />

41. Park in the La Estrella neighborhood<br />

42. Calderón Tejada Forest Park<br />

43. 20 de Julio Park<br />

44. Los Rosales Park<br />

45. Sebastián de Belalcázar Ave.

works in his words a lasting accomplishm<strong>en</strong>t and an ori<strong>en</strong>tating<br />

doctrine. Vargas Rubiano remembered the comm<strong>en</strong>ts<br />

of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> on top of Monserrate on projections of the<br />

population of the city, saying that it would not reach one million<br />

inhabitants, and his admiration of the transformation work<br />

of the Panóptico in the National Museum that was prepared<br />

for the 9th Pan-American Confer<strong>en</strong>ce of 1948.<br />

In the euphoria of his first visit, <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> was <strong>en</strong>ticed<br />

by the ICT to participate in the neighborhood Los Alcázares<br />

and to develop the prefabricated industry in Colombia with<br />

the support of ATBAT, the multidisciplinary cooperative that<br />

had formed around <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>’s atelier with great prestige<br />

in the Unité of Marseilles. 15 A significant amount of time<br />

passed before <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> was indeed in charge of the Pilot<br />

Plan of the city. Many things had interfered with the project,<br />

including interest, but mainly the 9th of April of 1948, which<br />

saw a series of fires and destruction in the heart of the city.<br />

This situation demanded the accelration of several courses of<br />

action. On the professional border, the Colegio de Ing<strong>en</strong>ieros<br />

y Arquitectos was formed in June of that year, predecessor<br />

of the future Cámara Colombiana de la Construcción, that<br />

brought together city professionals dedicated to the construction.<br />

Several main assignm<strong>en</strong>ts were considered: managing<br />

and using the t<strong>en</strong> million dollars that the International Bank of<br />

Reconstruction and Promotion had approved for the reconstruction<br />

of the city, adapting and adopting a law of horizontal<br />

property inspired by the Chilean experi<strong>en</strong>ce and necessary<br />

to regulate new types of developm<strong>en</strong>ts, cataloging and making<br />

visible the materials of the local industry of construction,<br />

demanding technical and city-planning definitions raised by<br />

the quick urban developm<strong>en</strong>t from authorities. 16 The immediate<br />

consequ<strong>en</strong>ce was the commission that Serrano, Ritter<br />

and Arango formed to handle the reconstruction and that tested<br />

the possible integration predial on the 7 th Carrera as form<br />

of r<strong>en</strong>ovation of the destroyed commercial sectors. The fury<br />

against Brunner in Proa shone th<strong>en</strong>, with the <strong>en</strong>dorsem<strong>en</strong>t of<br />

Rotival, that credited that Bogota’s architects only required the<br />

tutoring, at a distance, of international advisors. 17<br />

The presid<strong>en</strong>cy of Mariano Ospina Pérez was propitious<br />

for urban improvem<strong>en</strong>t. The presid<strong>en</strong>t founded a success-<br />

ful urbanizing and construction company in 1933, which had<br />

leaned on Brunner for many of its new neighborhoods and<br />

supported, through his public works ministers, substantial programs<br />

of infrastructure modernization. 18 At that time in Medellin,<br />

an original process for the urban developm<strong>en</strong>t occurred.<br />

From a 1920 law, Antioqueños’ businessm<strong>en</strong> headed by Jorge<br />

Restrepo Uribe had managed a national law that allowed them<br />

to carry out urban improvem<strong>en</strong>ts by valuation. 19 Although at<br />

the outset these were made first and the contributions of the<br />

taxed properties were collected later, the instrum<strong>en</strong>t became<br />

serious through a municipal office that made outstanding profits<br />

in works like breaking canals and forming new routes. Restrepo<br />

invited <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> to Medellin to interest him in formulating<br />

a pilot plan for that city, thinking that the cost of the study<br />

could be tak<strong>en</strong> later from the same works that the valuation<br />

managed. The valuation of the Antioqueños would ext<strong>en</strong>d to<br />

Bogota, Cali, and Barranquilla in the following years, with unequal<br />

success, perhaps due to cultures and local policies that<br />

contrasted with the associative tradition of the region. In any<br />

case, although <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> and Sert m<strong>en</strong>tioned several times<br />

in the correspond<strong>en</strong>ce the plans that were commissioned from<br />

them, this original instrum<strong>en</strong>t of financing and urban project<br />

managem<strong>en</strong>t—without a doubt inherited from the colonial systems<br />

of special taxes for public works—was not quantified,<br />

analyzed, or formally incorporated to those proposals. In a<br />

confid<strong>en</strong>tial memorandum on valuation in 1950, possible criteria<br />

for their application were m<strong>en</strong>tioned. 20<br />

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the foreigners were<br />

learning in Colombia. In the notebooks there appear refer<strong>en</strong>ces<br />

to Pizano and the Catalan vault and in the correspond<strong>en</strong>ces<br />

of <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>, Wi<strong>en</strong>er, and Sert there is praise for<br />

Solano’s vaults, and for the <strong>en</strong>thusiasm and quality of the<br />

teams of young people. Within these teams there were differ<strong>en</strong>t<br />

temperam<strong>en</strong>ts, like those of Gaitán Cortés or Arbeláez<br />

Camacho. The first one, a technocrat, a politician, was interested<br />

with Sert, from Tumaco, in the urban plans. His multiple<br />

roles as a professional, public functionary, industrial and<br />

academic official seemed to exemplify the ambitious task of<br />

bringing to the Colombian context the international state-ofthe-art.<br />

Germán Téllez speaks to us of their dean at the time 21<br />

(note six) and on the obvious differ<strong>en</strong>ce betwe<strong>en</strong> the Corbusian<br />

faith that Germán Samper showed against the criticisms<br />

that Francisco Pizano put forth with respect to the effort of<br />

the plan. 22 After an int<strong>en</strong>se race in 1966, Gaitán Cortés culminated<br />

his recognized mayorship with a plan of the city for<br />

following the 25 years.<br />

As a first director of the Office of the Regulatory Plan for<br />

Bogota (OPRB), until November of 1949, Herbert Ritter had<br />

tak<strong>en</strong> care of the meeting in Cap Martin in August of that year<br />

and maintained correspond<strong>en</strong>ce with the teams in Paris and<br />

New York. In 1949, in the correspond<strong>en</strong>ce on the Pilot Plan,<br />

there was announced the study on public services of the<br />

OPRB where it was explained that the Bogota River was ess<strong>en</strong>tial<br />

for the rear area public networks to produce almost all<br />

the electricity of Bogota and to form the base of the irrigation<br />

in the savannah. It was c<strong>en</strong>tral within the recomm<strong>en</strong>dations to<br />

begin the studies on the river and to create a commission on<br />

the river constituted by the people in charge of services and<br />

hygi<strong>en</strong>e in Bogota. 23<br />

In November of 1949 Ritter was succeed by Arbeláez, who<br />

came from the National Buildings Directory and was a member<br />

of the CIAM—and therefore a guarantee for the consultants.<br />

24 He was dilig<strong>en</strong>t in taking care of the local pressures<br />

in routes and, mainly, validating the developm<strong>en</strong>ts that the<br />

OPRB advanced. A conservative, he maintained a key proximity<br />

with the mayor and the presid<strong>en</strong>t (note 8). With Francisco<br />

Pizano and an increasing team of architects and <strong>en</strong>gineers,<br />

the OPRB transformed from a group of pupils to critics<br />

or competitors in the developm<strong>en</strong>t of ideas and prototypes,<br />

like those of the neighborhood units. The OPRB did their first<br />

tests trying schemes of neighborhoods with unité type buildings<br />

which TPA was inclined to view positively because of<br />

their principles, reason why would be necessary to let them<br />

do the proposals until review them with <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>. 25 The<br />

technical assembly that supposed the OPRB allowed to have<br />

previously dispersed information, like the schemes of commercial<br />

growth, distribution of population and activity of construction<br />

of house per years. 26<br />

Notes for a context on the Pilot Plan and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota | Hernando Vargas Caicedo<br />

67

It is very clear that the mayoralty of Santiago Trujillo Gómez<br />

(from April 1949 to July 1952) imposed pressure in time, detail,<br />

and clear expression of products of the contracted plan.<br />

This mayor, a constructor in the Trujillo Gómez Company and<br />

the Cardinal y Martínez Cárd<strong>en</strong>as, carried out tasks as work<br />

minister until being promoted to manager of the new-born<br />

Petroleum’s Public Company. Like Arbeláez, Trujillo concluded<br />

his tasks in the mayoralty and the OPRB and fulfilled the<br />

technical and political objective of developing and of making<br />

public the Pilot Plan that, finally, after its secret developm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

and failed exhibition in September of 1950, appeared in May<br />

of 1951—sustained in dispositions that assured against the<br />

<strong>en</strong>mity from the Municipal Council and the anxiety of the private<br />

developers. 27<br />

Examining the their correspond<strong>en</strong>ces in the period of elaboration<br />

of the plan, the sil<strong>en</strong>ce of the consultants on what the<br />

ICT was doing in the matter of processes, neighborhoods and<br />

constructive systems is noticeable, particularly in the case of<br />

Muzú, which is reverted wh<strong>en</strong> Sert demands the authorship<br />

of the prototypes of Quiroga. Minister <strong>Le</strong>yva had undertak<strong>en</strong><br />

the superblocks of CUAN (C<strong>en</strong>tro Urbano Antonio Nariño),<br />

from the data obtained in the tour in charge of the architects to<br />

Mexico, 28 and a total hermetism occurred on the appearance<br />

in Bogota of the CINVA since 1951, becoming a species of<br />

anti-model for the CIAM approach, like a school of technicians<br />

that bet on the disciplinary mixture, to the mixed zoning, to<br />

the communitarian participation, to the technological developm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

with local means. 29<br />

The proximity and distance of the group of Proa with respect<br />

to the Pilot Plan has be<strong>en</strong> examined before. It is a history<br />

of confusions and few gratitudes, which began with the<br />

murder of the father wh<strong>en</strong> Brunner was relegated, the master<br />

who was losing control successively on his proposals in Bogota,<br />

Medellin, and Cali. It is possible that the cooling and<br />

later criticism of Martinez for the Pilot Plan would also have<br />

had to do with political partisan issues. Clearly, the intermediate<br />

plan and its reports were put under code of sil<strong>en</strong>ce, so<br />

that the correspond<strong>en</strong>ce registers an unusual situation wh<strong>en</strong><br />

Sert recomm<strong>en</strong>ds what and how to say it, the OPRB and the<br />

mayor control the publicity on the verge of justifying increas-<br />

68 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

ing nonconformity by the product abs<strong>en</strong>ce or results until irremediably<br />

sp<strong>en</strong>ding the credit of the project and its authors.<br />

A key oppon<strong>en</strong>t, Brown Manuel Umaña, repres<strong>en</strong>ted the interest<br />

of the traditional builders against the radicalism of the<br />

Corbusian typologies. 30<br />

The city underw<strong>en</strong>t great changes in form, nature, and<br />

scale from the turn of the c<strong>en</strong>tury. The first detailed plan, created<br />

by the Pearson house in 1907, showed a very small city,<br />

with the ear of Chapinero. This contrasted with the one of<br />

Bucle, of 1933, that showed a proliferation of districts in all<br />

directions, which was formed for the first time in the photomosaic<br />

of aerial images of 1935. In successive illusion, the<br />

agreem<strong>en</strong>ts on urban perimeter, in 1940, and zoning, in 1944,<br />

face the crude reality of the plane of clandestine parceling of<br />

1950, in the sc<strong>en</strong>e of the elaboration of the plans by the international<br />

consultants and the OPRB. 31 Finally, the proposal of<br />

order of the plan director in 1950, the Pilot Plan in 1951, and<br />

the Regulatory Plan in 1953, are considered the culmination<br />

of the hypothetical series of states of the city in history, from<br />

1538 to 1938. The city had be<strong>en</strong> projected and its possible<br />

history had be<strong>en</strong> constructed.<br />

After the city planners, the economists<br />

In def<strong>en</strong>se of the Pilot Plan, the OPRB declared their gospel:<br />

On the arrival of the industry and the automobile, the streets<br />

became narrowed, the perimeter and the urban operational<br />

range were ext<strong>en</strong>ded sudd<strong>en</strong>ly and the fields and the villages<br />

were left by the promises of the new city. The consequ<strong>en</strong>ces<br />

were the destruction of the existing harmony, the city began<br />

their developm<strong>en</strong>t without order nor reason, until acquiring an<br />

abnormal ext<strong>en</strong>sion. The private interests speculated more<br />

and more with remote urbanizations, and at the pres<strong>en</strong>t time<br />

the city is led the problem of an exaggerated ext<strong>en</strong>sion. We<br />

write down the disturbed growth of the city moved away from<br />

all human activity, at the same time that its t<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>cy to transform<br />

itself into a linear city of a precise Biology. They are multitude<br />

of empty areas in the zones destined to housing, emptiness<br />

coveted by the earth speculation. 32<br />

This affirmation contrasted with that of Currie, years later:<br />

Two of the truly amazing developm<strong>en</strong>ts that distinguish the<br />

past c<strong>en</strong>tury and a half from the previous ones were the demographic<br />

explosion and the urbanism. As its time, in the<br />

countries economically more advanced, in the last 30 years,<br />

urbanism is becoming metropolitanism that is almost <strong>en</strong>dless<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sions of suburbs betwe<strong>en</strong> and around the urban c<strong>en</strong>ters.<br />

The automation of agriculture and the means of urban<br />

transportation, followed by means of individual transportation,<br />

made possible this trem<strong>en</strong>dous growth in the radical<br />

numbers and changes in the conditions of life and <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t.<br />

They are illustrations of how the technology and the<br />

economy model our world and our lives.<br />

The dynamics of these processes have not stopped working.<br />

By the way, in Colombia, as in other underdeveloped countries,<br />

we were in the departure point of <strong>en</strong>ormous processes<br />

that will make the country almost unrecognizable within a few<br />

years, relatively. The administrative mechanism to execute<br />

this policy could be a Ministry of Urban Issues to formulate<br />

plans and to provide inc<strong>en</strong>tives and ties or impedim<strong>en</strong>ts to<br />

obtain a balanced urban developm<strong>en</strong>t; offices of planning<br />

and ag<strong>en</strong>cies of urban r<strong>en</strong>ovation in all the big cities to carry<br />

out the policy to unite the room with the work, that characterized<br />

the urban life during 3,000 years until the 19th c<strong>en</strong>tury;<br />

a system of subsidies, if necessary, to resist the costs of the<br />

r<strong>en</strong>ovation and the high values of earth near the c<strong>en</strong>ters.<br />

Other fundam<strong>en</strong>tal elem<strong>en</strong>ts in an urban policy must be to<br />

provide suitably that the transit goes around the cities, the<br />

location of the markets wholesale and the slaughter houses<br />

on the periphery of the city, and facilities for diversions of the<br />

urban inhabitants in the field. 33<br />

The Bogota of the beginning of the 1950s moved quickly. The<br />

Colombian economy was accelerated to the tune of the international<br />

growth of the postwar period and the urban sc<strong>en</strong>e<br />

registered new hotels, like the Tequ<strong>en</strong>dama Hotel, in 1951;<br />

warehouses of of North American chains like Sears, in 1953;<br />

services of domiciliary gas, in 1954; the project of the Official<br />

Administrative C<strong>en</strong>ter, in 1955; the reorganization of<br />

the OPRB, in 1956, with the Office of District Planning. After

the height of the city planners, the new star from 1949 was<br />

Lauchlin Currie, outstanding propeller of railroads, regional<br />

institutions of planning, authorities and, finally, studies and<br />

urban policies: economic rationality, institutions, and mechanisms<br />

were their platform. 34 His study for the World Bank<br />

continues to be an example of synthetic docum<strong>en</strong>tation of a<br />

country that was looking into the developm<strong>en</strong>t from its rurality<br />

and that bet on that which Lleras Camargo called “our<br />

industrial revolution”. 35 In there, numbers on the increasing<br />

needs of housing, forms of financing, systems of planning for<br />

infrastructures are considered.<br />

Against the economic rationalism, the Pilot Plan had its<br />

provoking rhetoric: “Urbanism is a social task that tries to<br />

lead the modern society towards the harmony. The world has<br />

a necessity for harmony and to let itself be guided by the<br />

harmonizing ones”. 36 He briefly talked about the human problems<br />

of the city (Human Geography), summarizing in some<br />

dim<strong>en</strong>sions the poor material, cultural, and social conditions:<br />

sanitary overcrowding, services, the abs<strong>en</strong>ce of kitch<strong>en</strong>s,<br />

wage cost in drink, lack of formation of trades, time of mobilization<br />

of the workers, and basic education. And he summarized<br />

characteristics of a city to surpass that, instead of<br />

a culvert, had the “old Spanish sewer”, with space for automobiles,<br />

since the railroad was considered “perfectly uneconomical”,<br />

equipped with a “world-wide airport” plus the<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sion of the pres<strong>en</strong>t airport, where “each neighborhood<br />

is a perfect organism”, with a “rational subdivision of the city”<br />

and, as a bone of cont<strong>en</strong>tion, a “civic c<strong>en</strong>ter that reunites in a<br />

spiritual and material harmony the set of collective functions”,<br />

where to reunite the “history of the city without rupture and<br />

abandonm<strong>en</strong>t”. It was conceded that “this plan has studied<br />

everything, it has anticipated it for a total accomplishm<strong>en</strong>t”.<br />

It was made to notice that the new perimeter included 3,000<br />

additional hectares and works for the following five years<br />

were tak<strong>en</strong> into account.<br />

As well, Arbeláez answered the critics of the plan, 37 making<br />

commitm<strong>en</strong>ts to the new class of the team of technicians<br />

that, besides necessary technical knowledge, must have:<br />

[...] a very high work spirit and the goal of improving oneself<br />

… conditions for observing consci<strong>en</strong>tiously, to deduce<br />

the logic conclusions and knowledge to adapt to the positive<br />

resolutions … to own a special temperam<strong>en</strong>t that allows him<br />

to accept the suggestions of the conglomerate to whom he<br />

is working, as long as they have reasonable bases of good<br />

faith or int<strong>en</strong>tion and that they persecute in the long run the<br />

same goal.<br />

Gracefully, and possibly more important than majesty of the<br />

consultants or the prince, he thought that “the public opinion<br />

must be considered, since the planning that goes ahead has<br />

a ess<strong>en</strong>tially democratic character, because it wants to b<strong>en</strong>efit<br />

many without stopping hearing everything that it should<br />

be said on the matter. But also the office can have an opinion<br />

about the criticism”. He was hurt by the accusation about the<br />

“contrast betwe<strong>en</strong> the creative imagination (is worth to say<br />

the fantasy) and the existing reality” since “the exhibition corresponds<br />

in its scale to a doll’s game and that here everything<br />

appears clean, healthy, and without problems”.<br />

He added that the Pilot Plan:<br />

is just a First draft [sic] that in g<strong>en</strong>eral lines solves a problem<br />

as complex as the urban zoning. Each case in particular<br />

must be studied and be solved by a living organism that constitutes<br />

the Office of the Regulating Plan, which will have to<br />

remain investigating the g<strong>en</strong>eral conditions of the city.<br />

Against the dogma of the team of the plan, it was clear that<br />

this was the signal of mass exodus because of the news that<br />

the press gave on the CIAM in Hoddesdon. On <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>,<br />

it reported:<br />

[...] because of his poetic exaltation forgot to perhaps treat<br />

points less beautiful, but more important: did the project<br />

contemplate the conditions, possibilities and social needs<br />

of the country. Was it in agreem<strong>en</strong>t with the principles of<br />

the Ath<strong>en</strong>s Charter? … Vieco indicated the existing similarity<br />

betwe<strong>en</strong> the social conditions of India and Colombia<br />

with respect to undernourishm<strong>en</strong>t, illiteracy and lack of assistance.<br />

If the Regulatory Plan of Bogota was studied with<br />

the same criterion, will be more detrim<strong>en</strong>tal that b<strong>en</strong>eficial,<br />

he said. The civic c<strong>en</strong>ter with a presid<strong>en</strong>tial palace of 2,000<br />

squared meters of reception left out much more important<br />

problems to be solved or without ev<strong>en</strong> beginning to study<br />

them, at least. It was spok<strong>en</strong> of knowing how to extract traditional<br />

values and to appreciate the climactic conditions of<br />

our countries and to take into account the conditions of life<br />

and the differ<strong>en</strong>ce of classes, education and hygi<strong>en</strong>e defici<strong>en</strong>cy.<br />

The explanations that the masters gave left without<br />

answering these questions. 38<br />

In the afternoon, Germán Samper maintained that:<br />

technically, the problems are well resolved but the limitation<br />

of the urban area (by effects of the plan) would valorize the<br />

lands included inside the limits of it, favoring in this way a<br />

minority that owns them and increasing in price the housing<br />

for the poor classes.<br />

From the Pilot Plan to the Regulatory Plan: from the<br />

dreams to the practices<br />

After the visionary and <strong>en</strong>unciative condition of the Pilot Plan,<br />

victim of the pre-statistical age in which it was developed, the<br />

consultant’s contract of the Regulatory Plan meant a commitm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

to details and advice much more concrete. The city<br />

moved much faster than the studies and it was necessary to<br />

propose criteria and refer<strong>en</strong>ts of clear and immediate use.<br />

It auto-defined a plan that “indicates your rules, it indicates<br />

a way and forms a program that must govern the ordered<br />

and harmonic developm<strong>en</strong>t of the city, correcting errors committed<br />

in the past and trying to avoid their repetition in the<br />

future”. And it was pointed out that its “suggestions and standard<br />

percepts… [sic] do not repres<strong>en</strong>t a rigid criteria and<br />

its variety allows very diverse solutions”. It was necessary<br />

to surpass the vices and to op<strong>en</strong> “great av<strong>en</strong>ues that begin<br />

anywhere, do not go nowhere and frequ<strong>en</strong>tly they finish in<br />

the funnel of the old city”, possibly alluding to rec<strong>en</strong>t large<br />

roadways, like the Av<strong>en</strong>ue of the Americas or the 10 th Carrera.<br />

In this context, in which the services of aqueduct, sewage<br />

system, and electricity did not bear on the urban growth,<br />

with buildings v<strong>en</strong>tilated by small patios, norms as the Act<br />

Notes for a context on the Pilot Plan and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota | Hernando Vargas Caicedo<br />

69

70 <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> in <strong>Bogotá</strong>: Precisions around the Master Plan<br />

Urbanization plans drawn by Ospinas & Cia, Fernando Mazuera & Cia and Olcasa betwe<strong>en</strong> 1940 and 2000.

21 of 1944 had regulations on incomplete and contradictory<br />

heights, backward movem<strong>en</strong>ts, patios, and ties. 39<br />

The problem of the evolution, control, and taxation of the<br />

values of the urban ground was just outlined, making m<strong>en</strong>tion<br />

of the initiatives of Ernesto González Concha on unique tax,<br />

and did not appear anywhere in refer<strong>en</strong>ces to the valuation<br />

system that already was an effective fact in Medellin and organized<br />

in Cali, Barranquilla, and Bogota. It was assumed to<br />

be possible to fix the top value of the land and the planes of<br />

economic contours of the municipality were m<strong>en</strong>tioned. The<br />

plan was designed to be a flexible g<strong>en</strong>eral frame in its details<br />

and rigid in its basic principles, giv<strong>en</strong> the impossibility of exactly<br />

predicting the growth of Bogota during next fifty years,<br />

which would require knowing all the changes that can affect<br />

the national and international economy. The report of Wi<strong>en</strong>er<br />

and Sert included plans 1 to 5,000 and 1 to 2,000, graphical<br />

standards, three volumes of informative material and bibliography.<br />

Part of it talked about how continuing the organization<br />

of the OPRB, daughter of its advice since September 1948, to<br />

press for measures to avoid the growth of clandestine urbanizations,<br />

to conceive systems of road intersections with several<br />

successive phases of developm<strong>en</strong>t with bridged rotaries<br />

after round points.<br />

The difficulty of advance without an embryonic regulatory<br />

frame was se<strong>en</strong>. At that time Luis Cordova Mariño, advisory<br />

legal of the OPRB, dominated the process. A regional<br />

authority would have to be created as rapidly as possible<br />

and the municipalities incorporated before the developm<strong>en</strong>t<br />

of the population of the initial phase happ<strong>en</strong>ed. The marginal<br />

subdivisions that had multiplied quickly in the last years<br />

had to be limited, reorganized, and included in a regional<br />

plan. One imagined that it could be effective to control of<br />

deeds of extra-peripheral urbanizations and that the same<br />

perimeter (inheritance of the “feudal urbanism” of Brunner)<br />

could be used. At the same time, it was maintained that it<br />

was necessary to use special norms for spontaneous parcellings<br />

and that it was conv<strong>en</strong>i<strong>en</strong>t to use low-cost material<br />

in the form of premolded elem<strong>en</strong>ts for workers’ housing and<br />

that it was necessary to facilitate the purchase of lots with<br />

elem<strong>en</strong>tary services.<br />

After the change that 9 April unleashed on the commerce<br />

of the c<strong>en</strong>ter to take it to Chapinero, 40 new typologies of space<br />

for this activity were considered: American type markets, like<br />

those Carulla had just finished op<strong>en</strong>ing, and they were considered<br />

in the CUAN: shopping c<strong>en</strong>ters, according to the<br />

models of the latest criteria on local neighboring commerce<br />

advocated by committees of housing of the United States.<br />

Before the abs<strong>en</strong>ce of other promoters, it was proposed that<br />

the blocks were impelled by the insurance ag<strong>en</strong>cies, the<br />

banks and the state. The city would need two decades to establish<br />

financing mechanisms suffici<strong>en</strong>t to support a volume<br />

of construction like the one that was implicit in the plan and<br />

its d<strong>en</strong>sities.<br />

In order to achieve the image of a great nation’s capital, many<br />

actions were necessary: prohibiting dispersed chircales, to<br />

continue the reforestation, developing monum<strong>en</strong>tal buildings<br />

according to North American models and standards, lighting,<br />

v<strong>en</strong>tilation, accessibility, services, emerg<strong>en</strong>cy exits, batteries<br />

of elevators and parking, besides lodging for the employees of<br />

ministries in appropriate zones. Already from the Geologic Service<br />

Report of 1949, questions regarding construction and operations<br />

in hills were considered, although the OPRB would not<br />

demonstrate specifically how to handle slope urbanizations,<br />

secular subject of the Colombian Andean city 41 and data from<br />

the collectors that, in the OPRB, were handled by the team that<br />

Jorge Forero directed in sewage system networks. 42<br />

The urban traffic was quantified for the first time with the<br />

studies by the consultants Seeyle, Stev<strong>en</strong>son, Vaue, and<br />

Knecht, on capacities, movem<strong>en</strong>t of vehicles in critical hours,<br />

peripheral parking. They m<strong>en</strong>tioned parking meters; parking<br />

inside the blocks; in streets, cellars, and buildings of several<br />

floors; wh<strong>en</strong> in Bogota the cellars were still a peculiarity. With<br />

a population of 700,000 inhabitants, Bogota had only 20,000<br />

cars that, nevertheless, were a problem in the congested<br />

c<strong>en</strong>ter. It was necessary to offer for the CBD 9520 maint<strong>en</strong>ances<br />

plus a peripheral maint<strong>en</strong>ance of 4,000 positions.<br />

The imagined city must have an area of 6,577 hectares in<br />

order to lodge the projected population of 1,653,242 inhabitants<br />

after 50 years, handling d<strong>en</strong>sities of 200, 300, 350 and<br />

400 inhabitants by hectare in differ<strong>en</strong>t zones. It was an imperative<br />

for the urbanism of three dim<strong>en</strong>sions, the elimination<br />

of mixed zones, indices FAR to control constructed d<strong>en</strong>sities,<br />

front yards, adapted standards for urbanizations of mountain,<br />

superblocks surrounded by gre<strong>en</strong> areas in apartm<strong>en</strong>ts of<br />

more than t<strong>en</strong> floors, construction in series or in masses, a<br />

series of linear parks.<br />

The problem of the evolution, control, and taxation on the<br />

values of the urban ground was just outlined, making m<strong>en</strong>tion<br />

to the initiatives of Ernesto González Concha on unique<br />

tax, and did not appear any where refer<strong>en</strong>ces to the valuation<br />

system that already was an effective fact in Medellin and was<br />

organized in Cali, Barranquilla and Bogota. Planes of economic<br />

contours of the municipality were m<strong>en</strong>tioned.<br />

All this int<strong>en</strong>tion required that the OPRB, organized in the<br />

way of the Planning Departm<strong>en</strong>t, would guarantee a stable<br />

technical nucleus and would assure their visibility: “For being<br />

able to execute the plan, it is necessary to make the citiz<strong>en</strong>ship<br />

in g<strong>en</strong>eral understand the conv<strong>en</strong>i<strong>en</strong>ce and public utility.<br />

One is due to explain to them that the plan is for the g<strong>en</strong>eral<br />

good of the city, that it affects the life of all. The plan must<br />

become popular”.<br />

Nostalgic, it praised “the small towns with colonial places<br />

of great <strong>en</strong>chantm<strong>en</strong>t” and it was hoped in the new city to restore<br />

the concept of vicinity, giving each sector its own character<br />

or personality. The creation of the Special District was a<br />

necessity. 43 Already in Medellin, TPA had raised the issue of<br />

a municipal association of future and lasting consequ<strong>en</strong>ces.<br />

Behind the contractual sequ<strong>en</strong>ce of analysis of the city<br />

was a preliminary basic scheme. Pilot Plan, Regulatory Plan,<br />

developm<strong>en</strong>t and application of the plan, the provocations of<br />

the new illegal parcellings, congestion, overcrowding, inadequate<br />

speculation on the ground, and construction had g<strong>en</strong>erated<br />

a series of answers on perimeter, roadways, superblocks,<br />

interv<strong>en</strong>tion of the ground, governm<strong>en</strong>tal systems of<br />

parks, and buildings that proposed radical innovations. This<br />

ambitious set demanded an unconscious distribution of roles<br />

around the idea. On the one hand, <strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong> repres<strong>en</strong>ted<br />

emotion, the poetics and the dreams. The SCA personified<br />

the initial impulse raising the positive factors of the initiative.<br />

Notes for a context on the Pilot Plan and the Regulatory Plan of Bogota | Hernando Vargas Caicedo<br />

71

Like devil’s advocate, the set of the developers behaved as<br />

snipers throughout the evolution of the plans. Wanting to be<br />

neutral and objective, the OPRB team talked about data and<br />

realities. Finally, like coordinator and main tutor, the TPA team<br />

was the true facilitator with seriousness, s<strong>en</strong>iority solutions<br />

and organizational capacity. Simplifying the organizational<br />

scheme that nobody designed, the SCA had suggested<br />

what to do; Mazuera had found why to support it; Trujillo had<br />

determined wh<strong>en</strong> to obtain it; the OPRB had proposed where<br />

to fulfill it; TPA had prescribed with whom to develop it; and<br />

<strong>Le</strong> <strong>Corbusier</strong>, with Wi<strong>en</strong>er and Sert had considered how it<br />

would be.<br />

The reality of the new urbanization in the following decades<br />