The effects of puma prey selection and specialization on ... - Panthera

The effects of puma prey selection and specialization on ... - Panthera

The effects of puma prey selection and specialization on ... - Panthera

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mammalogy, 94(1):000–000, 2013<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> less abundant<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Patag<strong>on</strong>ia<br />

L. MARK ELBROCH* AND HEIKO U. WITTMER<br />

Wildlife, Fish, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Biology, 1088 Academic Surge, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA<br />

95616, USA (LME, HUW)<br />

School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biological Sciences, Victoria University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wellingt<strong>on</strong>, P.O. Box 600, Wellingt<strong>on</strong> 6140, New Zeal<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> (HUW)<br />

* Corresp<strong>on</strong>dent: lmelbroch@ucdavis.edu<br />

Populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> generalist foragers may in fact be composed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals that select different <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>. We<br />

m<strong>on</strong>itored 9 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Puma c<strong>on</strong>color) in Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia using Argos–global positi<strong>on</strong>ing system (Argos-GPS)<br />

technology for a mean <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9.33 m<strong>on</strong>ths 6 5.66 SD. We investigated 694 areas where <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> locati<strong>on</strong> data were<br />

spatially aggregated, called GPS clusters, at which we identified 433 kill sites <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6 acts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> scavenging. Pumas as<br />

a populati<strong>on</strong> specialized up<strong>on</strong> guanacos (Lama guanicoe), whereas <strong>on</strong>ly 7 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s specialized<br />

up<strong>on</strong> guanacos. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> specialized up<strong>on</strong> domestic sheep (Ovis aries) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 up<strong>on</strong> European hares (Lepus<br />

europaeus) in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed. Male <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> female <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s selected different distributi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibited <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> at both the individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> level. Three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibited<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> when we compared individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> use to <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability within individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s’ home ranges. One<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> selected endangered huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 selected sheep. When we compared individual<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> use to <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> use at the populati<strong>on</strong> level, 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s differed from the populati<strong>on</strong> norm. Whereas <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s did<br />

not select huemul at the populati<strong>on</strong> level, 2 individuals did select huemul. Two individuals also selected<br />

domestic sheep, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these 2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s was substantial enough to result in a populati<strong>on</strong>-level effect.<br />

Our research highlights the need to determine whether <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibit individual foraging variati<strong>on</strong> throughout<br />

their range, the extrinsic factors associated with (<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> possibly influencing) such variati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> how <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that<br />

select rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> less abundant species in multi<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> systems impact recovering <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Key words: diet, European hare, global positi<strong>on</strong>ing system (GPS) cluster, guanaco, Hippocamelus, Lama, Patag<strong>on</strong>ia, Puma,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ó 2013 American Society <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mammalogists<br />

DOI: 10.1644/12-MAMM-A-041.1<br />

Animals can be categorized broadly as generalist or<br />

specialist foragers, although populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> generalist foragers<br />

may in fact be composed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals that select different<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> (e.g., Estes et al. 2003; Matich et al. 2011; Woo et al.<br />

2008). Predators exhibit <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> when they c<strong>on</strong>sume a<br />

particular <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> disproporti<strong>on</strong>ately to its availability (Estes et al.<br />

2003; Knopff <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boyce 2007), or when they select a <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

disproporti<strong>on</strong>ately to the populati<strong>on</strong> norm. Following Knopff<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boyce (2007), we differentiate <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> from <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, which describes the <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species composing the<br />

majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a predator’s diet. Based <strong>on</strong> these definiti<strong>on</strong>s, a<br />

predator can select <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> specialize <strong>on</strong> another.<br />

Across taxa, individuals within many populati<strong>on</strong>s exhibit<br />

different <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (see Estes et al. 2003; Matich et al.<br />

2011); yet, neither the theoretical implicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variable<br />

intraspecific <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> nor the populati<strong>on</strong>-level c<strong>on</strong>sequences<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predators selecting or specializing <strong>on</strong> a particular<br />

0<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in multi<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> systems are currently well understood (Estes<br />

et al. 2003; Pettorelli et al. 2011). Historically, biologists<br />

assumed that predator populati<strong>on</strong>s exhibited a ‘‘mean’’ foraging<br />

strategy <strong>on</strong> a ‘‘mean’’ <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> representative <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>n they employed functi<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>ses (Holling 1959) to<br />

model the foraging behavior <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ‘‘mean’’ predator with<br />

changes in the availability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘‘mean’’ <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, an approach that<br />

may underestimate or overestimate the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predators<br />

up<strong>on</strong> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> when there are specialist predators in the<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> (Pettorelli et al. 2011).<br />

Generalist foraging in multi<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> systems establishes scenarios<br />

for apparent competiti<strong>on</strong> between <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> that share predators<br />

(Holt 1977), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> apparent competiti<strong>on</strong> is a mechanism that can<br />

www.mammalogy.org

0 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY<br />

Vol. 94, No. 1<br />

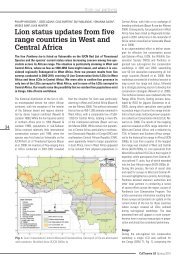

FIG. 1.—Locati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> study site in Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia. Inset illustrates l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ownership across the area, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the thick black outline delineates the<br />

boundaries <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the future Patag<strong>on</strong>ia Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> smaller black rectangle delineates the actual study area in which we m<strong>on</strong>itored <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

(Puma c<strong>on</strong>color). LCNR ¼ Lago Cochrane Nati<strong>on</strong>al Reserve.<br />

drive declines in rare species (DeCesare et al. 2010). In<br />

apparent competiti<strong>on</strong>, predators that <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> multiple <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> can<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tinue unsustainable predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> rare species because they<br />

are subsidized by alternative <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> (DeCesare et al. 2010).<br />

Because different foraging <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibited by different<br />

individuals may be taught to their <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring (Estes et al.<br />

2003) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> persist for years (Estes et al. 2003; Woo et al. 2008),<br />

the potential impact that relatively few, l<strong>on</strong>g-lived predators<br />

that either select or specialize <strong>on</strong> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> may have <strong>on</strong> rare<br />

species in natural systems is important both in theoretical <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

applied c<strong>on</strong>texts. For example, Williams et al. (2004) estimated<br />

that a pod <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 orcas (Orcinus orca) that specialized <strong>on</strong> sea<br />

otters (Enhydra lutris) could kill 8,500 otters each year.<br />

Further, they calculated that if just 4.4% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the estimated orca<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> surrounding the Aleutian archipelago (170 individuals)<br />

specialized <strong>on</strong> sea otters, then orcas could drive the entire<br />

Aleutian Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sea otters to extincti<strong>on</strong> in 3–4<br />

m<strong>on</strong>ths (Williams et al. 2004). Thus, research efforts that<br />

explore the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predators that select or specialize <strong>on</strong><br />

rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the viability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s are critical<br />

(Pettorelli et al. 2011).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Puma c<strong>on</strong>color) is a large, solitary felid with the<br />

broadest geographic range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any terrestrial mammal in the<br />

Western Hemisphere (Sunquist <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sunquist 2002). Increasing<br />

evidence suggests that individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibit varied <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (Knopff <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boyce 2007; Murphy <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ruth 2010),<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> that individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that select or specialize <strong>on</strong> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

can severely affect the populati<strong>on</strong> viability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> those <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

(Festa-Bianchet et al. 2006; Ross et al. 1997; Sweitzer et al.<br />

1997). For example, a single female <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed 8.7% (n ¼ 11)<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 26.1% (n ¼ 6) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the spring lambs in a small bighorn sheep populati<strong>on</strong> in a<br />

single year (Ross et al. 1997). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>refore, we tested whether<br />

individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibited varied <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> if so,<br />

whether <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> by individuals differed from <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

exhibited by the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> as a whole. More<br />

importantly, we sought to determine how differences in<br />

individual- versus populati<strong>on</strong>-level <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> influenced less<br />

abundant <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in natural systems.<br />

An underst<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual- versus populati<strong>on</strong>-level<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is essential to the management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that select<br />

rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>. In resp<strong>on</strong>se to severe <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> rare species,<br />

c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> scientists c<strong>on</strong>tinue to debate whether depredati<strong>on</strong><br />

permits, the removal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that select or<br />

specialize <strong>on</strong> rare species, or wide-scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> culling, either<br />

through direct acti<strong>on</strong> or indirectly through raising harvest<br />

quotas, is the best strategy to aid rare species recovery (Cougar<br />

Management Guidelines Working Group 2005; Robins<strong>on</strong> et al.<br />

2008; Rominger 2007). When few individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s select rare<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> patterns at the populati<strong>on</strong> level will be<br />

subject to stochastic changes in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> (Festa-<br />

Bianchet et al. 2006); therefore, the removal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that select rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> rather than populati<strong>on</strong>-level<br />

management will be more effective in reducing predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>

M<strong>on</strong>th 2013 ELBROCH AND WITTMER—PUMA PREY SELECTION IN PATAGONIA<br />

0<br />

rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>. In c<strong>on</strong>trast, when many <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s select rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in<br />

proporti<strong>on</strong> to their availability, management that targets<br />

individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s will be ineffective. Instead, populati<strong>on</strong>-level<br />

management will be the better strategy to reduce predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong><br />

rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Patag<strong>on</strong>ia is a large (.1,000,000-km 2 ), sparsely populated<br />

regi<strong>on</strong> below latitude 398S in southern Chile <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Argentina,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> an area in which the foraging ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s remains<br />

poorly understood (Walker <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Novaro 2010). Nevertheless,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>–livestock c<strong>on</strong>flict <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> endangered<br />

huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovering guanaco<br />

(Lama guanicoe) populati<strong>on</strong>s are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> increasing c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>cern (Flueck 2009; Kissling et al. 2009; Walker <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Novaro<br />

2010; Wittmer et al., in press). In additi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets in<br />

southern South America have primarily been documented in<br />

areas where <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> are largely exotic, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> based <strong>on</strong> scat analyses,<br />

with the identity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the predator species unc<strong>on</strong>firmed with<br />

genetic tests (Franklin et al. 1999; Iriarte et al. 1991; Novaro et<br />

al. 2000; Palacios et al. 2012; Rau <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Jiménez 2002; Yáñez et<br />

al. 1986). Four <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 6 published studies <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets based<br />

<strong>on</strong> scat analyses in Patag<strong>on</strong>ia reported that <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

specialized <strong>on</strong> European hares (Lepus europaeus—Franklin et<br />

al. 1999; Novaro et al. 2000; Rau <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Jiménez 2002; Yáñez et<br />

al. 1986). Of the 5 studies completed in areas actually inhabited<br />

by European hares, researchers reported that hares c<strong>on</strong>tributed<br />

40% to <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets (Franklin et al. 1999; Iriarte et al. 1991;<br />

Novaro et al. 2000; Rau <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Jiménez 2002; Yáñez et al. 1986).<br />

Nevertheless, we must account for the fact that it is comm<strong>on</strong> to<br />

c<strong>on</strong>fuse the scats <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different carnivore species (Elbroch et al.<br />

2012; Farrell et al. 2000; Janečka et al. 2011). For example,<br />

Janečka et al. (2011) reported that in a study in which<br />

researchers targeted snow leopard (Uncia uncia) scats <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> used<br />

associated signs such as footprints <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> scrapes to facilitate<br />

positive identificati<strong>on</strong>, genetics later c<strong>on</strong>firmed that 57% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 146<br />

scats identified in the field as snow leopard were in fact red fox<br />

(Vulpes vulpes). Lacking the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic tools required to<br />

identify <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> scats, we suspect that researchers in previous<br />

studies <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets in Patag<strong>on</strong>ia misclassified some fox scats<br />

as <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>, thus biasing their findings toward small <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Further,<br />

without genetic analyses, scat analysis does not allow<br />

researchers to assess the influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual specialist<br />

predators <strong>on</strong> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential misidentificati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> scats <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the need to calibrate <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass remains<br />

found in scats using digestibility coefficients to estimate actual<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers killed (Ackerman et al. 1984; Gamberg <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Atkins<strong>on</strong> 1988) may have cultured a distorted underst<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> foraging ecology in southern South America. In order to<br />

better incorporate research <strong>on</strong> the diets <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

to provide alternative data to scat-based research, we decided to<br />

employ global positi<strong>on</strong>ing system (GPS) technology to study<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets in Patag<strong>on</strong>ia.<br />

New <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> improving GPS technology has facilitated our<br />

underst<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the foraging ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> large carnivores<br />

through increasing the detecti<strong>on</strong> probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their kill sites in<br />

the field <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> allowing us to compare the variable diets <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

individuals (e.g., Cavalcanti <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gese 2010; Knopff et al.<br />

2009). Dietary analyses based <strong>on</strong> GPS clusters, however, also<br />

have potential biases, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> may miss or underestimate the<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> small <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> to <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> energetics (Bac<strong>on</strong> et al.<br />

2011). This is because <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s may not remain in place l<strong>on</strong>g<br />

enough to create a cluster when c<strong>on</strong>suming small <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, or<br />

researchers may not locate the remains, if any exist.<br />

Nevertheless, we argue that investigating GPS clusters to<br />

study foraging ecology is particularly well suited to <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

other solitary felids because felids <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten ‘‘pluck’’ <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> drop the<br />

fur <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> at least a porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, even mammals as small as<br />

hares (L. M. Elbroch, pers. obs.). In c<strong>on</strong>trast, some canids<br />

scatter <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains, or c<strong>on</strong>sume small <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> more completely,<br />

so cluster analysis may prove less suited for studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> canid<br />

foraging ecology.<br />

Here we report <strong>on</strong> the foraging ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as determined through GPS<br />

tracking <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 animals (4 males <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 females) in the future<br />

Patag<strong>on</strong>ia Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park, Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia. We c<strong>on</strong>firmed<br />

the identities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> by visiting potential ‘‘kill sites’’<br />

identified by spatially clustered GPS locati<strong>on</strong>s (called GPS<br />

clusters—Anders<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lindzey 2003). In our study area,<br />

native <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass exceeded that <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>native species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the complete array <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> native large- <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> medium-sized<br />

vertebrates still coexisted <strong>on</strong> the l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> community<br />

included approximately 120 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 1,000 endangered huemul<br />

still remaining in Chile (Jiménez et al. 2008), up<strong>on</strong> which the<br />

influence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> remains <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> immediate c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>cern (Corti et al. 2010; Wittmer et al., in press), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

2,500 sheep (Ovis aries), a c<strong>on</strong>tinued source <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human–<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>flict across much <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>’s distributi<strong>on</strong> in South<br />

America (Kissling et al. 2009).<br />

Given the potential for variable <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> by individual<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s to influence populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> less abundant <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

such as huemul <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> domestic sheep, we tested the following<br />

hypotheses. Because guanacos were the most abundant <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

in our study area (Elbroch <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wittmer 2012), we<br />

hypothesized that c<strong>on</strong>trary to earlier published accounts,<br />

individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a populati<strong>on</strong> would specialize<br />

<strong>on</strong> guanacos, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> that male <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> female <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s would kill<br />

guanacos <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> equivalent health. We also hypothesized that<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in Patag<strong>on</strong>ia would exhibit foraging strategies similar<br />

to those in North America (Knopff <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boyce 2007; Ross et<br />

al. 1997), with individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s exhibiting preferences for<br />

different species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>. We hypothesized that <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> would select rare huemul, but that few individuals<br />

would do so. Further, we hypothesized that few <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s would<br />

select domestic sheep, but rather eat them in proporti<strong>on</strong>s equal<br />

to or less than expected given their availability in the study<br />

area. To test these hypotheses, we compared <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sumed<br />

by the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>, as determined by investigating GPS<br />

clusters, with <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability in the study area, as well as<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sumed by individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s with the distinctive <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

availabilities within each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their respective home ranges, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

with the proporti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species selected by<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a populati<strong>on</strong>.

0 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY<br />

Vol. 94, No. 1<br />

MATERIALS AND METHODS<br />

Study area.—Our study covered approximately 1,100 km 2 in<br />

the southern porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Chile’s Aysén District, immediately<br />

north <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lago Cochrane in central Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia<br />

( 72.23008S, 47.120008W; Fig. 1). It included the 69-km 2<br />

Lago Cochrane Nati<strong>on</strong>al Reserve, the 690-km 2 private Estancia<br />

Valle Chacabuco, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> approximately 440 km 2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 1,611km<br />

2 Jeinimeni Nati<strong>on</strong>al Reserve; these 3 areas will be<br />

combined into the future Patag<strong>on</strong>ia Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park (http://<br />

www.c<strong>on</strong>servaci<strong>on</strong>patag<strong>on</strong>ica.org/). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cover was<br />

characteristic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rugged Patag<strong>on</strong>ia mountains <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> was a<br />

mixture <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 dominant cover classes: open Patag<strong>on</strong>ian<br />

steppe; high-elevati<strong>on</strong> deciduous forests dominated by lenga<br />

(Noth<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>agus pumilio); <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower-elevati<strong>on</strong> shrub communities<br />

dominated by ñirre (N. antarctica) interspersed with chaura<br />

(Pernettya mucr<strong>on</strong>ata) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> calafate (Berberis microphylla)<br />

shrubs. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area supported large numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> native<br />

guanacos <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a small populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> endangered huemul<br />

(Elbroch <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wittmer 2012; Wittmer et al., in press).<br />

European hares were abundant in all habitats, especially in<br />

scrub communities, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> approximately 2,500 sheep <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 150<br />

cows were kept in the eastern porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the estancia. Culpeo<br />

foxes (Lycalopex culpaeus) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> several scavenger birds,<br />

including Andean c<strong>on</strong>dors (Vultur gryphus), southern<br />

caracaras (Caracara plancus), Chimango caracaras (Milvago<br />

chimango), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> black-chested buzzard eagles (Geranoaetus<br />

melanoleucus) were comm<strong>on</strong>. Bey<strong>on</strong>d the borders <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the future<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al park, sheep farming was the most comm<strong>on</strong> l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> use.<br />

Captures <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> collar programming.—Our capture<br />

procedures adhered to guidelines approved by the American<br />

Society <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mammalogists (Sikes et al. 2011), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> were<br />

approved by the independent Instituti<strong>on</strong>al Animal Care <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Use Committee at the University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> California, Davis. We<br />

captured <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s from March to September in 2008 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2009,<br />

when locating them was facilitated by the presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> snow <strong>on</strong><br />

the ground. When c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s were suitable, we traveled <strong>on</strong><br />

horseback until fresh <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> tracks were found, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> used hounds<br />

to force <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s to retreat to either a tree or rocky outcrop where<br />

we could safely approach an animal. Pumas were anesthetized<br />

with ketamine (2.5–3.0 mg/kg) administered with a dart gun,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> then lowered to the ground where they were administered<br />

medetomidine (0.075 mg/kg) by syringe. We fitted <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s with<br />

either an Argos-GPS collar (Argos collar, SirTrack, Havelock<br />

North, New Zeal<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>; Tellus Collar, Televilt, Lindesberg,<br />

Sweden; or Lotek 7000saw, Lotek Wireless, Newmarket,<br />

Ontario, Canada) or very-high-frequency collar (SirTrack), the<br />

weights <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which were ,3% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult female weights in the<br />

study area, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ,2% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult males. Once an<br />

animal was completely processed, the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the capture<br />

drugs were reversed with atipamezole (0.375 mg/kg), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s departed the capture sites <strong>on</strong> their own.<br />

Collars were programmed to acquire GPS locati<strong>on</strong>s at 2-h<br />

intervals, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> transmit data through an Argos uplink at 2- to 5day<br />

intervals. Our most comm<strong>on</strong> programming was a 6-h<br />

Argos uplink every 3 days to relay GPS locati<strong>on</strong> data. Elbroch<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wittmer (2012) provide further details about the collars<br />

deployed in our study.<br />

Field investigati<strong>on</strong>s.—Up<strong>on</strong> retrieval, locati<strong>on</strong> data were<br />

displayed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> distances between c<strong>on</strong>secutive <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> locati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were calculated in ArcGIS 9.1 (ESRI, Redl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, California).<br />

We defined GPS clusters (Anders<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lindzey 2003) as any<br />

2þ points within 150 m <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each other, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> CyberTrackercertified<br />

observers (Elbroch et al. 2011; Evans et al. 2009)<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted field investigati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any cluster where 1 GPS<br />

locati<strong>on</strong> was made during the hours <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crepuscular light or<br />

periods <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> darkness. Observers located the areas associated<br />

with clusters using h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>held Garmin Etrex <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Venture models<br />

(Garmin Internati<strong>on</strong>al, Inc., Olathe, Kansas). We investigated<br />

every cluster, even those made completely within daylight<br />

hours, for the first 2 m<strong>on</strong>ths <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the project. Because the daytime<br />

clusters never revealed predati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> required significant time<br />

to check (each <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> would make 1–3 short daytime clusters<br />

per day), we chose not to investigate clusters with durati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

completely within daylight hours for the remainder <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

project <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to assume that they were day beds rather than kills.<br />

We did not include the day cluster investigati<strong>on</strong>s made early in<br />

the project in our analyses.<br />

We used <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains, including hair, skin, rumen or<br />

stomach, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> b<strong>on</strong>e fragments to identify <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains, including the locati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bite marks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

what had been eaten, were used to determine whether the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

had killed the animal or was scavenging. For ungulates, we<br />

marked the locati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the rumen as the kill site with h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>held<br />

Garmin GPS units (accuracy 5–10 m). For smaller <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the<br />

stomach or intestines when they were available, or the largest<br />

collecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any remains, was marked as the kill site.<br />

To help future researchers gauge what area they need to<br />

investigate while searching for <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains, we measured the<br />

distance between kill sites marked with a h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>held GPS in the<br />

field <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the nearest <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> GPS locati<strong>on</strong> associated with that<br />

kill. We defined the time until investigati<strong>on</strong> as the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

days between the day the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> departed a GPS cluster <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

day the site was investigated by an observer. If an observer<br />

visited a kill site that was still active or <strong>on</strong> the same day the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> departed the GPS cluster, the time until investigati<strong>on</strong> was<br />

recorded as 0. We used logistic regressi<strong>on</strong> to test whether the<br />

time until investigati<strong>on</strong> str<strong>on</strong>gly indicated whether kill remains<br />

were found at a GPS cluster.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong>, we opportunistically identified additi<strong>on</strong>al fresh<br />

kills by unmarked <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by following tracks found in the field<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> following scavenging birds, particularly Andean c<strong>on</strong>dors<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> caracara. Kills were attributed to <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

when tracks c<strong>on</strong>firmed their presence at the site, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> when bite<br />

marks, wounds, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> signs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> struggles indicated that they were<br />

not scavenging. We included these data in descriptive analyses<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets for our study area that dealt with <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>, but not in the analyses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> or<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Prey indexes.—We counted numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

calculated biomass <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> to better reflect their energetic<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> diets. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> age <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> guanacos up to 24

M<strong>on</strong>th 2013 ELBROCH AND WITTMER—PUMA PREY SELECTION IN PATAGONIA<br />

0<br />

m<strong>on</strong>ths old were determined using tooth erupti<strong>on</strong> sequences in<br />

the lower m<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ible (Raedeke 1979). We estimated the m<strong>on</strong>thly<br />

weights <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1-year-old (chulengos) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2-year-old guanacos<br />

using linear growth estimates, a birth weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 12.7 kg, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1year<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2-year weights <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 42 kg <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 100 kg, respectively<br />

(Sarno <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Franklin 1999). Guanacos . 2 years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> age were<br />

estimated to weigh 120 kg (Raedeke 1979). Guanacos . 2<br />

years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> age were c<strong>on</strong>sidered adults <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their sex was<br />

determined by measuring the mass <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a lower canine<br />

(Raedeke 1979).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>ly data available for growth rates in huemul were an<br />

estimated birth weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 kg (Flueck <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Smith-Flueck<br />

2005). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g>refore, we applied growth allometry for the<br />

structurally similar mule deer (Odocoileus hemi<strong>on</strong>us; 0.21<br />

kg/day—Anders<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wallmo 1984) to estimate weights <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

huemul , 1 year old. We estimated weights <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> huemul 1–3<br />

years old based <strong>on</strong> growth rates reported for mule <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> whitetailed<br />

deer (O. virginianus—Putnam 1988). We used a weight<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 65 kg for adult huemul (.3 years—Iriarte Walt<strong>on</strong> 2008).<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> ages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> huemul up to 3.5 years old were estimated using<br />

tooth erupti<strong>on</strong> sequences. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> sex <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> huemul was determined<br />

using external morphology, including genitalia <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> antlers. For<br />

small <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g>, we assumed 4 kg for European hares (the mean<br />

weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 30 specimens hunted by locals or killed by vehicles<br />

in our study area), 2 kg for Patag<strong>on</strong>ian haired armadillos<br />

(Chaetophractus villosus—Iriarte Walt<strong>on</strong> 2008), 9 kg for<br />

culpeo foxes (Iriarte Walt<strong>on</strong> 2008), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6.4 kg for upl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> geese<br />

(Chloephaga picta—Todd 1996).<br />

Franklin et al. (1999) used punctures in the crania <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

guanacos to identify <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> guanacos in Torres del<br />

Paine Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park. To assess whether this method accurately<br />

estimated the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> guanacos killed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, we<br />

carefully inspected the crania <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ibles from a subset <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

guanaco kills by <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in our study area for tooth marks. We<br />

then quantified the percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> skulls in each guanaco age<br />

class that held tooth marks that betrayed <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

When possible, we estimated the relative health <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult<br />

guanacos <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> huemul from a field analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the b<strong>on</strong>e marrow<br />

in a femur. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> marrow was scored 1–3 <strong>on</strong> 2 characteristics,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> these were summed to yield a scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2–6, with 2<br />

reflecting very poor health <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6 reflecting good health. First<br />

the marrow was scored for color: 1 for red–brown, 2 for pink,<br />

or 3 for white. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, we scored marrow for texture: 1 for<br />

very loose or runny or in extreme cases partly missing to 3 for<br />

firm. We employed an analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> variance to assess whether<br />

male <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> female <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s killed guanacos <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> equivalent health.<br />

Time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> kills <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> durati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> GPS clusters.—We defined the<br />

time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> kill as the time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 1st GPS locati<strong>on</strong> gathered by a<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> collar within 150 m <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a kill site. We defined the cluster<br />

length as the total hours from the 1st to the last GPS locati<strong>on</strong><br />

within 150 m <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the kill site, even when the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> moved<br />

farther from the kill site but returned while using the site.<br />

Preferential <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.—We defined <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> for<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> as the killing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species in greater<br />

proporti<strong>on</strong>s than expected given their availability. To do this,<br />

we used habitat-specific <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> abundances (discussed below) as<br />

an index for <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability. We used a chi-square goodness<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>-fit<br />

test to determine 2nd-order resource <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (Johns<strong>on</strong><br />

1980; see Cavalcanti <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gese [2010] for an example with<br />

jaguars [<strong>Panthera</strong> <strong>on</strong>ca]), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> whether <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a populati<strong>on</strong><br />

selected any <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their 4 primary <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> species (as determined<br />

from site investigati<strong>on</strong>s) in our study area in greater abundance<br />

than their availability would suggest. To account for variable<br />

samples am<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, we divided the biomass killed for each<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> type by each <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> by the total biomass each killed before<br />

testing for 2nd-order resource <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Next, we used chi-square goodness-<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>-fit tests to determine<br />

3rd-order resource <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (Johns<strong>on</strong> 1980). We did this by<br />

testing <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed by individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s against 2 different<br />

indexes for <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability. First, we used <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> abundances as<br />

an index for <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability to test whether individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

killed <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in proporti<strong>on</strong>s to their availabilities within each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

their respective home ranges. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, we used 2nd-order<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as an index for <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability to test whether<br />

individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s selected <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in the same proporti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

selected by <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a populati<strong>on</strong>. When results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the chisquare<br />

tests were significant, we employed B<strong>on</strong>ferr<strong>on</strong>i Z-tests<br />

to determine which <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> proporti<strong>on</strong>s were statically different<br />

from expected (Byers et al. 1984).<br />

We estimated <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> densities in different habitats using<br />

program Distance 6.0 (Thomas et al. 2010), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> these data<br />

were reported in Elbroch <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wittmer (2012). Program<br />

Distance determines detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> animals at<br />

different distances from transects, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> then quantifies their<br />

densities. We applied the estimates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6,550 guanacos, 120<br />

huemul, 21,973 hares, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2,500 sheep to our study area, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

then multiplied these by specific <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> weights described above<br />

to estimate available biomass. We used adult weights for all<br />

animals, except guanacos. During transect sampling for<br />

guanacos, the percent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1st-year animals am<strong>on</strong>g mixed groups<br />

also was calculated (19%) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> we multiplied this proporti<strong>on</strong> by<br />

the weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6-m<strong>on</strong>th-old chulengos (27.3 kg) to reflect actual<br />

biomass <strong>on</strong> the l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape more realistically. For sheep, we<br />

used adult weights because nearly all the lambs were sold <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f<br />

each Christmas at 2 m<strong>on</strong>ths <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> age.<br />

Prey <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.—We defined <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as<br />

killing a <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> in greater abundance than any other <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Knopff<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Boyce 2007), both at the populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> individual levels.<br />

We quantified <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

killed, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> total biomass <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed.<br />

RESULTS<br />

Prey indexes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> GPS cluster characteristics.—We<br />

m<strong>on</strong>itored 8 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s using Argos-GPS technology (2 SirTrack<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6 Lotek 7000s), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> using the stored GPS data in<br />

the collar because its Argos capabilities failed (Tel<strong>on</strong>ics collar)<br />

for a mean <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9.33 m<strong>on</strong>ths 6 5.66 SD. We investigated 694<br />

GPS clusters, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> located <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains at 63.3% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these,<br />

including 433 kill sites <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6 scavenging sites. Kill sites were<br />

located <strong>on</strong> average 8 m 6 14.2 SD away from the nearest <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

locati<strong>on</strong> data.

0 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY<br />

Vol. 94, No. 1<br />

FIG. 2.—Prey indexes in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> A) numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> B)<br />

kilograms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass killed for <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Puma c<strong>on</strong>color) as a<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> kilograms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed by C) males <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> D) females<br />

in Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia, 2008–2009.<br />

We c<strong>on</strong>ducted field investigati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Argos-relayed GPS<br />

clusters within 11 days 6 12 SD (range, 0–78 days) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the time<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> left the area. We did not use the stored data in the<br />

malfuncti<strong>on</strong>ing collar in the analysis <strong>on</strong> time until investigati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

because site investigati<strong>on</strong>s for this animal were c<strong>on</strong>ducted<br />

<strong>on</strong> average 792 6 87 days (range, 650945 days) after the <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

had left the area. Probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> locating <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains was<br />

inversely correlated with time until investigati<strong>on</strong> (rs ¼ 0.01 n ¼<br />

609, P ¼ 0.02).<br />

Prey animals included 350 ungulates <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 83 small to<br />

medium-sized vertebrates (Figs. 2A <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2B). Sixty-four<br />

percent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> kills were made at night, 26% during crepuscular<br />

hours, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 10% during the day (Fig. 3). <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> probability that<br />

observers would discover <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> remains did not show a<br />

relati<strong>on</strong>ship with cluster length until 14 h, at which the<br />

probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> locating a kill increased with the durati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time<br />

a <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> spent at a cluster: 2 h (42% yielded kills), 4 h (52%), 6<br />

h (43%), 8 h (37%), 10 h (59%), 12 h (46%), 14 h (73%), 16 h<br />

(91%), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 18 h (98%). Kills were found 100% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the time at<br />

clusters . 18 h, with the excepti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 large clusters created<br />

by females at den sites (196 h for F4 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 258 h for F5). In<br />

every case <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> scavenging, male 2 (M2) comm<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>eered<br />

FIG. 3.—Percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Puma c<strong>on</strong>color) kills made in<br />

Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia, 2008–2009, in 3 time categories by m<strong>on</strong>th <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> year.<br />

Backdrop <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> labels <strong>on</strong> the right side <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the figure illustrate the hours<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> sunlight through the year.<br />

guanacos killed by marked females (4 from F3 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 from<br />

F4). We also identified 30 fresh guanacos killed by unmarked<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (17 chulengos <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 13 subadults <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> adults).<br />

Male <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> female <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s selected <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> differently (v 2 6 ¼<br />

123.38, n ¼ 433, P , 0.0001). Accounting for the age <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their variable weights, guanacos c<strong>on</strong>stituted 88.5% (96.6%<br />

for females <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 79.3% for males), domestic sheep c<strong>on</strong>stituted<br />

8.7% (0% for females <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 19.1% for males), European hares<br />

c<strong>on</strong>stituted 1.9% (1.9% for females <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 0% for males), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

endangered huemul c<strong>on</strong>stituted 0.9% (1.3% for females <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

1.6% for males) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total biomass killed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Figs. 2C <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

2D). Guanacos were by far the primary <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s at our<br />

study site, both in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers killed (n ¼ 332) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

biomass (23,248 kg; Figs. 2A <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2B).<br />

Males <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> females killed guanacos <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> equivalent health<br />

(F1,137 ¼ 0.55, n ¼ 138, P . 0.46); the mean marrow index was<br />

4.46 6 1.31 SD. Of 139 adult guanaco kills for which sex<br />

could be determined reliably, 67 (48.2%) were female <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 72<br />

(51.8%) were male. Only 84 (87.5%) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 96 chulengos killed, 6<br />

(60%) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 10 2nd-year guanacos, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 (25%) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 35 adult<br />

guanacos exhibited <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> teeth marks <strong>on</strong> the head or m<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ible.<br />

We documented 7 huemul killed by 2 marked <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. M2<br />

killed 2 adult females . 7 years old, both <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which were<br />

unhealthy <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> exhibited porous, brown b<strong>on</strong>e marrow (marrow<br />

scores <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2). F4 killed 5 huemul, including 1 fawn <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> unknown<br />

sex, 2 yearlings (1 male <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 female), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a subadult male<br />

estimated to be 3.5 years old. All huemul killed by F4<br />

exhibited healthy b<strong>on</strong>e marrow.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s spent at a cluster increased with<br />

the estimated size <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed (rs ¼ 0.23, n ¼ 414, P ,<br />

0.0001; Fig. 4), but the relati<strong>on</strong>ship showed c<strong>on</strong>siderable

M<strong>on</strong>th 2013 ELBROCH AND WITTMER—PUMA PREY SELECTION IN PATAGONIA<br />

0<br />

FIG. 4.—Regressi<strong>on</strong> analysis between weight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

global positi<strong>on</strong>ing system (GPS) cluster (h) for GPS-collared <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

(Puma c<strong>on</strong>color) in Chilean Patag<strong>on</strong>ia, 2008–2009.<br />

scatter. <str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> heaviest <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> (120 kg) were recorded at GPS<br />

clusters occupied as briefly as 2 h.<br />

Preferential <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.—<str<strong>on</strong>g>The</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

exhibited 2nd-order <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> domestic sheep <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

avoidance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> European hares (Table 1). When comparing <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>selecti<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> to <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> availability, 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> selected huemul <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2<br />

selected sheep (Table 1). When comparing individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> use<br />

to the proporti<strong>on</strong>s selected by the populati<strong>on</strong> as a whole, 2<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s selected sheep, 1 selected guanacos, 1 selected huemul,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 selected European hares (Table 2).<br />

Prey <str<strong>on</strong>g>specializati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.—In terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

biomass <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed, <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as a populati<strong>on</strong> highly<br />

specialized up<strong>on</strong> guanacos. Individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g>s also specialized<br />

up<strong>on</strong> guanacos in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both number <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

killed, except in 2 cases. M4 specialized <strong>on</strong> domestic sheep in<br />

terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass. F5 specialized <strong>on</strong><br />

European hares in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>prey</str<strong>on</strong>g> killed, but<br />

specialized <strong>on</strong> guanacos in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biomass killed.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

Our use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> GPS technology to study <str<strong>on</strong>g>puma</str<strong>on</strong>g> foraging ecology<br />

provided radically different results than research reliant up<strong>on</strong><br />