Chapters 1 - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Chapters 1 - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Chapters 1 - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

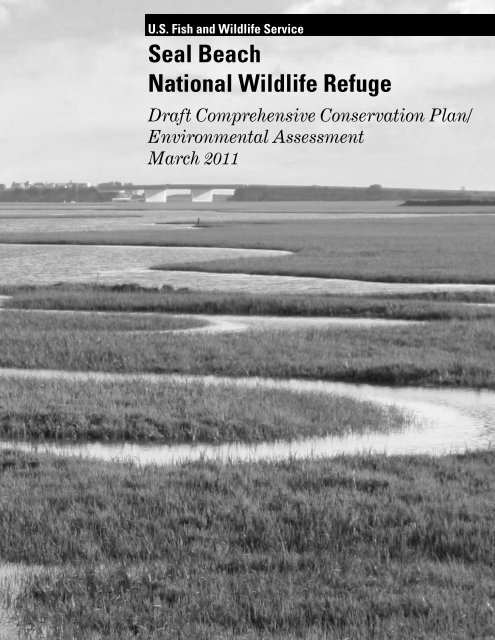

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

Seal Beach<br />

National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/<br />

Environmental Assessment<br />

March 2011

Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long-term guidance for management decisions <strong>and</strong> set<br />

forth goals, objectives, <strong>and</strong> strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes <strong>and</strong> identify the<br />

<strong>Service</strong>’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are<br />

sometimes substantially above current budget allocations <strong>and</strong>, as such, are primarily for <strong>Service</strong><br />

strategic planning <strong>and</strong> program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment<br />

for staffing increases, operational <strong>and</strong> maintenance increases, or funding for future l<strong>and</strong><br />

acquisition.

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> & <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

Seal Beach<br />

National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/<br />

Environmental Assessment<br />

March 2011<br />

Vision Statement<br />

Tidal channels me<strong>and</strong>ering through a sea of cordgrass deliver moisture <strong>and</strong><br />

nourishment to support a healthy marsh ecosystem. As the quiet calm of the<br />

morning is interrupted by the clacking of a light-footed clapper rail, school<br />

children <strong>and</strong> other visitors, st<strong>and</strong>ing on the elevated observation deck, point<br />

with excitement in the direction of the call hoping for a glimpse of the rare<br />

bird. Shorebirds dart from one foraging area to another feasting on what<br />

appears to be an endless supply of food hidden within the tidal flats.<br />

California least terns fly above the tidal channels searching for small fish to<br />

carry back to their nests on NASA Isl<strong>and</strong>. A diverse array of marine<br />

organisms, from tube worms <strong>and</strong> sea stars to rays <strong>and</strong> sharks, <strong>and</strong> even an<br />

occasional green sea turtle, thrive within the tidal channels <strong>and</strong> open water<br />

areas of the Refuge’s diverse marsh complex, while Nelson’s sharp-tailed<br />

sparrows <strong>and</strong> other upl<strong>and</strong> birds find food <strong>and</strong> shelter within the native<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> vegetation that borders the marsh.<br />

U. S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

Pacific Southwest Region<br />

2800 Cottage Way, Room W-1832<br />

Sacramento, CA 95825-1846<br />

March 2011

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment<br />

Orange County, California<br />

Type of Action: Administrative<br />

Lead Agency: U.S. Department of the Interior, <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

Responsible Official: Ren Lohoefener, Regional Director, Pacific Southwest Region<br />

For Further Information: Victoria Touchstone, Refuge Planner<br />

San Diego NWR Complex<br />

6010 Hidden Valley Road, Suite 101<br />

Carlsbad, CA 92011<br />

(760) 431-9440 extension 349<br />

Abstract: This Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment (CCP/EA)<br />

describes <strong>and</strong> evaluates various alternatives for managing the Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

(NWR). Three alternatives, including a No Action Alternative (Alternative A) as required by the<br />

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations, are described, compared, <strong>and</strong> assessed<br />

for the Seal Beach NWR. The three alternatives are summarized below:<br />

Alternative A – No Action: This alternative assumes no change from past management<br />

programs <strong>and</strong> serves as the baseline to which all other action alternatives are compared.<br />

There would be no major changes in habitat management or the current public use program<br />

under this alternative.<br />

Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current Public Uses: Under<br />

this alternative, current wildlife <strong>and</strong> habitat management activities would be exp<strong>and</strong>ed to<br />

include evaluation of current baseline data for fish, wildlife, <strong>and</strong> plants on the Refuge,<br />

identification of data gaps, implementation of species surveys to address data gaps as staff<br />

time <strong>and</strong> funding allows, <strong>and</strong> support for new research projects that would benefit Refuge<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> Refuge management. Also proposed is the restoration of approximately 22<br />

acres of intertidal habitat (salt marsh <strong>and</strong> intertidal mudflat) <strong>and</strong> 15 acres of wetl<strong>and</strong>/upl<strong>and</strong><br />

transition habitat. Pest control would be implemented in accordance with an Integrated Pest<br />

Management (IPM) program <strong>and</strong> mosquito monitoring <strong>and</strong> control would be guided by a<br />

Mosquito Management Plan. No changes to the current public use program are proposed.<br />

Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration, Improve<br />

Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation: The majority of the management activities,<br />

including the IPM program <strong>and</strong> Mosquito Management Plan, proposed in Alternative B would<br />

also be implemented under this Alternative. The primary difference between Alternatives B<br />

<strong>and</strong> C is that under Alternative C a larger portion of the areas to be restored would consist of<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>/upl<strong>and</strong> transition habitat. Approximately 12 acres of currently disturbed<br />

upl<strong>and</strong> would be restored to native upl<strong>and</strong> habitat, about 10 acres would be restored to<br />

wetl<strong>and</strong>/upl<strong>and</strong> transition habitat, <strong>and</strong> approximately 15 acres would be restored to intertidal<br />

habitat. In addition, Alternative C includes limited expansion of the current public use<br />

program, including exp<strong>and</strong>ed opportunities for wildlife observation.<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment

Abstract <br />

The issues addressed in this Draft CCP/EA include the potential effects of the various alternatives<br />

on the physical environment, biological <strong>and</strong> cultural resources, <strong>and</strong> the social/economic<br />

environment. The adverse <strong>and</strong> beneficial effects of implementing the alternatives are generally<br />

described in the following action categories: habitat <strong>and</strong> wildlife management, pest management,<br />

<strong>and</strong> public use.<br />

Providing Comments: Your comments on the Draft CCP/EA should be mailed, faxed, or emailed<br />

to the San Diego NWR Complex no later than May 11, 2011. Comments should be mailed to:<br />

Victoria Touchstone<br />

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

San Diego NWR Complex<br />

6010 Hidden Valley Road, Suite 101<br />

Carlsbad, CA 92011<br />

Faxed comments should be directed to Victoria Touchstone at (760) 930-0256 <strong>and</strong> emailed<br />

comments should be directed to Victoria_Touchstone@fws.gov (please include “Seal Beach CCP”<br />

in the subject line).<br />

Comments should be provided to the <strong>Service</strong> during the public review period of this Draft<br />

CCP/EA. This will enable us to analyze <strong>and</strong> respond to the comments at one time <strong>and</strong> to use this<br />

input in the preparation of the Final CCP. Comments should be specific <strong>and</strong> should address the<br />

document’s adequacy <strong>and</strong> the merits of the alternatives described. Environmental objections that<br />

could have been raised at the draft stage may be waived if not raised until after the completion of<br />

the Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI).<br />

All comments received from the public will be placed in the <strong>Service</strong>’s record for this action. As part<br />

of the record, comments will be made available for inspection by the general public, <strong>and</strong> copies may<br />

be provided to the public. For persons who do not wish to have their names <strong>and</strong> other identifying<br />

information made available, anonymous comments will be accepted.<br />

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Reader’s Guide<br />

The U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong> will manage the Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge (NWR) in<br />

accordance with an approved Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP). This CCP provides long<br />

range guidance on Refuge management through its vision, goals, objectives, <strong>and</strong> strategies. The<br />

CCP also provides a basis for a long-term adaptive management process including implementation,<br />

monitoring progress, evaluating <strong>and</strong> adjusting, <strong>and</strong> revising plans accordingly. Additional stepdown<br />

planning will be required prior to implementation of certain programs <strong>and</strong> projects.<br />

This document combines both a Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan <strong>and</strong> Environmental<br />

Assessment (Draft CCP/EA). Following the completion of public review <strong>and</strong> evaluation of the<br />

comments received, the <strong>Service</strong> will identify the preferred alternative. Assuming no significant<br />

adverse effects are identified, the <strong>Service</strong> will also issue a Finding of No Significant Impact<br />

(FONSI). Once the FONSI is signed, the Final CCP will be prepared.<br />

The following chapter <strong>and</strong> appendix descriptions are provided to assist readers in locating <strong>and</strong><br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing the various components of the CCP/EA.<br />

Chapter 1, Introduction, includes the purpose of <strong>and</strong> need for the CCP <strong>and</strong> EA; an overview of the<br />

National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System; legal <strong>and</strong> policy guidance for planning for <strong>and</strong> managing the<br />

resources on National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuges; setting, regional context, <strong>and</strong> history of the Seal Beach<br />

NWR; <strong>and</strong> Refuge purposes, vision, <strong>and</strong> goals for future management.<br />

Chapter 2, The Planning Process, describes the CCP planning process, including the public<br />

involvement aspects of the process. This chapter also provides background on major planning<br />

issues identified by Refuge staff, Federal, Tribal, State, <strong>and</strong> local agencies, <strong>and</strong>/or the public, as<br />

well as a variety of management concerns <strong>and</strong> opportunities.<br />

Chapter 3, Alternatives, describes three management alternatives proposed for the Refuge. Each<br />

alternative represents a different approach to achieving the vision, goals, <strong>and</strong> objectives for the<br />

Refuge. Alternative A (No Action) describes current management practices. Alternative C is the<br />

proposed action.<br />

Chapter 4, Affected Environment, describes the existing physical <strong>and</strong> biological environment,<br />

public uses, cultural resources, <strong>and</strong> socioeconomic conditions. They represent baseline conditions<br />

for the comparisons made in Chapter 5.<br />

Chapter 5, Environmental Consequences, describes the potential impacts of each of the<br />

alternatives on the resources, programs, <strong>and</strong> conditions outlined in Chapter 4.<br />

Chapter 6, Implementation, presents the details of how the proposed action (Alternative C) for<br />

the Seal Beach NWR would be implemented if it is selected as the preferred alternative when the<br />

Final CCP is approved, including details regarding the objectives <strong>and</strong> strategies necessary to<br />

achieve the Refuge goals. This chapter also addresses step-down planning, adaptive management,<br />

compliance requirements, <strong>and</strong> Refuge operations, including funding <strong>and</strong> staffing proposals.<br />

Chapter 7, Reference Cited, provides bibliographic references for the citations in this document.<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment RG-1

Reader’s Guide <br />

Appendix A, Compatibility Determinations (draft), describe uses, anticipated impacts,<br />

stipulations, <strong>and</strong> a determination of compatibility for wildlife observation, interpretation, <strong>and</strong><br />

environmental education, as well as scientific research <strong>and</strong> mosquito management. The latter two<br />

uses also include a determination of appropriate use.<br />

Appendix B, List of Preparers, Planning Team Members, <strong>and</strong> Persons/Agencies Consulted,<br />

lists those individuals involved in the preparation of the CCP/EA, as well as those agencies<br />

consulted during the preparation of this planning document.<br />

Appendix C, Integrated Pest Management Program (draft), is a step-down management plan<br />

that provides guidance for managing pests on the Refuge, including invasive plant species control.<br />

This program does not address the control of mosquitoes.<br />

Appendix D, Mosquito Management Plan (draft), is a step-down management plan that presents<br />

a phased approach to mosquito management, including monitoring <strong>and</strong> control, on the Refuge.<br />

Appendix E, Federal <strong>and</strong> State Ambient Air Quality St<strong>and</strong>ards, presents the currently adopted<br />

Federal <strong>and</strong> State Ambient Air Quality St<strong>and</strong>ards.<br />

Appendix F, Species Lists, contains a list of the bird species observed on the Refuge, as well as<br />

additional lists for mammalian, plant, <strong>and</strong> reptile species that have been observed on the Refuge.<br />

Appendix G, Fire Management Plan Exemption, documents that the Seal Beach NWR has been<br />

exempted from the requirement to prepare a fire management plan.<br />

Appendix N, Wilderness Inventory, outlines the process used to determine that the Seal Beach<br />

NWR does not meet the criteria for a wilderness review or designation.<br />

Appendix I, Request for Cultural Resource Compliance Form, is an example of the form that<br />

must be submitted to initiate cultural resource review.<br />

Appendix J, Glossary of Terms, contains acronyms, abbreviations, <strong>and</strong> definitions of terms used in<br />

this document.<br />

Appendix K, Distribution List, contains the list of Federal, Tribal, State, <strong>and</strong> local agencies,<br />

nongovernmental organizations, libraries, <strong>and</strong> individuals who received notification of the<br />

availability of the Draft CCP/EA <strong>and</strong> other planning updates associated with this planning effort.<br />

RG-2 Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Table of Contents<br />

Chapter 1 – Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1-1<br />

1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1-1<br />

1.2 Purpose <strong>and</strong> Need for the Plan ............................................................................................ 1-1<br />

1.3 U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong> <strong>and</strong> National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System ........................... 1-4<br />

1.3.1 U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong> .................................................................................... 1-4<br />

1.3.2 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System .............................................................................. 1-4<br />

1.4 Legal <strong>and</strong> Policy Guidance .................................................................................................... 1-5<br />

1.4.1 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 ................................. 1-5<br />

Compatibility Policy .............................................................................................. 1-6<br />

Appropriate Use Policy ......................................................................................... 1-7<br />

Biological Integrity, Diversity <strong>and</strong> Environmental Health Policy ................. 1-8<br />

Wilderness Stewardship Policy ........................................................................... 1-9<br />

1.4.2 National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 ........................................................... 1-10<br />

1.5 Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ................................................................................ 1-10<br />

1.5.1 Location ....................................................................................................................... 1-10<br />

1.5.2 Physical Setting .......................................................................................................... 1-10<br />

1.5.3 Ecosystem Context .................................................................................................... 1-11<br />

Sonoran Joint Venture Bi-national Bird Conservation .................................. 1-12<br />

California <strong>Wildlife</strong> Action Plan .......................................................................... 1-12<br />

Watershed Management ..................................................................................... 1-12<br />

1.5.4 Refuge Purpose <strong>and</strong> Authority ................................................................................. 1-12<br />

1.5.5 Refuge Vision <strong>and</strong> Goals ............................................................................................ 1-13<br />

1.5.6 History of Refuge Establishment ............................................................................ 1-14<br />

Chapter 2 – The Planning Process ................................................................................... 2-1<br />

2.1 Preparing a Comprehensive Conservation Plan ................................................................ 2-1<br />

2.2 Preplanning ............................................................................................................................. 2-1<br />

2.3 Public Involvement in Planning ........................................................................................... 2-2<br />

2.4 Overview of Issues <strong>and</strong> Public Scoping Comments ........................................................... 2-3<br />

Habitat Management ................................................................................................... 2-3<br />

Threatened <strong>and</strong> Endangered Species Management ............................................... 2-3<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong>-Dependent Recreational Use ....................................................................... 2-3<br />

Research ........................................................................................................................ 2-3<br />

Refuge Operations ........................................................................................................ 2-3<br />

Expansion of the Refuge Boundary ........................................................................... 2-3<br />

2.5 Management Concerns/Opportunities ................................................................................ 2-4<br />

Climate Change/Sea Level Rise ................................................................................. 2-4<br />

Subsidence ..................................................................................................................... 2-4<br />

Invasive Species ............................................................................................................ 2-5<br />

Predation of Listed Species ........................................................................................ 2-5<br />

Contaminants ................................................................................................................ 2-5<br />

Refuge Access………………………………………………………………... 2-5<br />

Opportunities ................................................................................................................ 2-6<br />

2.6 Development of a Refuge Vision .......................................................................................... 2-6<br />

2.7 Development of Refuge Goals, Objectives, <strong>and</strong> Strategies .............................................. 2-6<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan i

Table of Contents <br />

2.8 Alternative Development Process ....................................................................................... 2-7<br />

2.9 Selection of theRefuge Proposed Action ............................................................................ 2-7<br />

2.10 Plan Implementation ............................................................................................................. 2-7<br />

Chapter 3 – Alternatives ..................................................................................................... 3-1<br />

3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3-1<br />

3.2 Alternative Development Process ....................................................................................... 3-1<br />

3.3 Past <strong>and</strong> Current Refuge Management .............................................................................. 3-2<br />

3.3.1 Background .................................................................................................................. 3-3<br />

3.3.2 Existing Management Plans ...................................................................................... 3-3<br />

3.3.3 Management History <strong>and</strong> Past Refuge Actions ...................................................... 3-4<br />

Management History ............................................................................................ 3-4<br />

Past Refuge Actions .............................................................................................. 3-4<br />

3.3.4 Coordination with NWSSB ......................................................................................... 3-5<br />

3.3.5 Current Refuge Management .................................................................................... 3-6<br />

3.4 Proposed Management Alternatives ..................................................................................... 3-7<br />

3.4.1 Summary of Alternatives ............................................................................................ 3-7<br />

Alternative A (No Action) .................................................................................... 3-7<br />

Alternative B .......................................................................................................... 3-7<br />

Alternative C (Proposed Action) ......................................................................... 3-7<br />

3.4.2 Similarities Among the Alternatives ......................................................................... 3-8<br />

3.4.2.1 Features Common to All Alternatives ............................................................ 3-8<br />

3.4.2.2 Features Common to All Action Alternatives .............................................. 3-10<br />

3.4.3 Detailed Description of the Alternatives ................................................................ 3-11<br />

3.4.3.1 Alternative A (No Action) ............................................................................... 3-11<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>and</strong> Habitat Management ........................................................... 3-11<br />

Public Use Program .................................................................................... 3-19<br />

Refuge Operations ...................................................................................... 3-20<br />

Environmental Contaminants Coordination ........................................... 3-20<br />

Cultural Resource Management ............................................................... 3-20<br />

Volunteeers <strong>and</strong> Partners .......................................................................... 3-21<br />

Mosquito Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Control............................................................3-21<br />

3.4.3.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current.... 3-23<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>and</strong> Habitat Management ............................................................ 3-23<br />

Habitat Restoration .................................................................................... 3-31<br />

Public Use Program .................................................................................... 3-33<br />

Refuge Operations ...................................................................................... 3-33<br />

Environmental Contaminants Coordination ........................................... 3-33<br />

Cultural Resource Management ............................................................... 3-33<br />

Volunteeers <strong>and</strong> Partners .......................................................................... 3-34<br />

3.4.3.3 Alternative C – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,Improve<br />

Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation ..................................................... 3-34<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>and</strong> Habitat Management ........................................................... 3-34<br />

Public Use Program .................................................................................... 3-38<br />

Refuge Operations ...................................................................................... 3-38<br />

Coordination with NWSSB........................................................................3-38<br />

Environmental Contaminants Coordination ........................................... 3-38<br />

Cultural Resource Management ............................................................... 3-38<br />

ii Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Table of Contents<br />

Volunteeers <strong>and</strong> Partners ................................................................................... 3-39<br />

3.4.4 Alternatives Considered but Eliminated from Detailed Analysis ....................... 3-39<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong> the Number of California Least Tern Nesting Sites ....................... 3-39<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong> the Refuge Boundary to Include the Los Cerritos Wetl<strong>and</strong>s ........ 3-39<br />

Include Oil Isl<strong>and</strong> into the Refuge Following Termination of Oil<br />

Production Activities .......................................................................................... 3-39<br />

Improve Public Access onto the Refuge ........................................................... 3-40<br />

3.4.5 Comparison of Alternatives by Issue ....................................................................... 3-40<br />

Chapter 4 –Refuge Resources ............................................................................................. 4-1<br />

4.1 Environmental Setting .......................................................................................................... 4-1<br />

4.1.1 Location <strong>and</strong> Property Description ........................................................................... 4-1<br />

4.1.2 Flyway Setting .............................................................................................................. 4-1<br />

4.1.3 Historic Setting ............................................................................................................. 4-3<br />

4.2 Physical Environment ........................................................................................................... 4-8<br />

4.2.1 Topography/Visual Quality ......................................................................................... 4-8<br />

4.2.2 Geology <strong>and</strong> Soils ........................................................................................................ 4-11<br />

4.2.3 Mineral Resources ...................................................................................................... 4-14<br />

4.2.4 Agricultural Resources .............................................................................................. 4-14<br />

4.2.5 Hydrology/Water Quality .......................................................................................... 4-15<br />

4.2.5.1 Hydrology .......................................................................................................... 4-15<br />

4.2.5.2 Water Quality .................................................................................................... 4-21<br />

4.2.5.3 Watershed Planning ......................................................................................... 4-27<br />

4.2.6 Climate/Climate Change/Sea Level Rise ................................................................ 4-28<br />

4.2.7 Air Quality ................................................................................................................... 4-30<br />

4.2.8 Greenhouse Gas Emissions ....................................................................................... 4-32<br />

4.2.9 Contaminants .............................................................................................................. 4-34<br />

4.3 Biological Resources .............................................................................................................. 4-37<br />

4.3.1 Regional <strong>and</strong> Historical Context .............................................................................. 4-37<br />

4.3.2 Regional Conservation Planning .............................................................................. 4-38<br />

4.3.2.1 Ecoregion/L<strong>and</strong>scape Conservation Cooperative Planning ....................... 4-38<br />

4.3.2.2 Applicable Species Recovery Plans ................................................................ 4-39<br />

4.3.2.3 Shorebird Conservation Planning .................................................................. 4-39<br />

4.3.2.4 Waterbird Conservation .................................................................................. 4-40<br />

4.3.2.5 Sonoran Joint Venture Bi-national Bird Conservation ............................... 4-40<br />

4.3.2.6 Marine Protected Areas .................................................................................. 4-41<br />

4.3.2.7 California <strong>Wildlife</strong> Action Plan ....................................................................... 4-41<br />

4.3.3 Habitat <strong>and</strong> Vegetation ............................................................................................. 4-41<br />

4.3.3.1 Shallow Subtidal Habitat ................................................................................. 4-42<br />

4.3.3.2 Intertidal Channels <strong>and</strong> Tidal Mudflat Habitats ......................................... 4-44<br />

4.3.3.3 Coastal Salt Marsh Habitat ............................................................................. 4-45<br />

4.3.3.4 Upl<strong>and</strong> Habitat ................................................................................................. 4-46<br />

4.3.3.5 Sensitive Plants ................................................................................................. 4-47<br />

4.3.4 <strong>Wildlife</strong> ........................................................................................................................ 4-47<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment iii

Table of Contents <br />

4.3.4.1 Birds ................................................................................................................... 4-47<br />

Wintering Birds ........................................................................................... 4-48<br />

Migrant Birds .............................................................................................. 4-48<br />

Summer Residents ...................................................................................... 4-48<br />

Year-Round Residents ............................................................................... 4-49<br />

4.3.4.2 Mammals ........................................................................................................... 4-49<br />

4.3.4.3 Reptiles <strong>and</strong> Amphibians ................................................................................ 4-50<br />

4.3.4.4 Terrestrial Invertebrates ................................................................................ 4-50<br />

4.3.4.5 Marine Invertebrates ...................................................................................... 4-55<br />

4.3.4.6 <strong>Fish</strong>es ................................................................................................................. 4-56<br />

4.3.5 Federally Listed Endangered <strong>and</strong> Threatened Species ...................................... 4-59<br />

4.3.5.1 California Least Tern ...................................................................................... 4-59<br />

4.3.5.2 Light-footed Clapper Rail ............................................................................... 4-63<br />

4.3.5.3 Western Snowy Plover .................................................................................... 4-67<br />

4.3.5.4 Salt Marsh Bird’s-beak .................................................................................... 4-68<br />

4.3.5.5 East Pacific Green Turtle ............................................................................... 4-69<br />

4.3.6 State Listed Species .................................................................................................. 4-70<br />

4.3.6.1 Belding’s Savannah Sparrow .......................................................................... 4-70<br />

4.3.7 Species of Concern <strong>and</strong> Other Special Status Species .......................................... 4-71<br />

4.3.8 Invasive Species ......................................................................................................... 4-75<br />

4.3.8.1 Invasive Plants .................................................................................................. 4-75<br />

4.3.8.2 Invasive Terrestrial Animals .......................................................................... 4-75<br />

4.3.8.3 Invasive Marine Organisms ............................................................................ 4-76<br />

4.4 Cultural Resources .............................................................................................................. 4-77<br />

4.4.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4-77<br />

4.4.2 Cultural Setting .......................................................................................................... 4-77<br />

4.4.2.1 Early Man (Initial Occupation – 7,500 B.P.) ................................................. 4-77<br />

4.4.2.2 Millingstone Period (7,500 – 3,000 B.P.) ........................................................ 4-78<br />

4.4.2.3 Intermediate Period (3,000 – 1,000 B.P.) ...................................................... 4-78<br />

4.4.2.4 Late Prehistoric Period (1,000 B.P. – 1800 A.D.)......................................... 4-78<br />

4.4.2.5 Ethnohistory ..................................................................................................... 4-79<br />

4.4.2.6 Historic Period .................................................................................................. 4-79<br />

4.4.3 Existing Cultural Resources Investigations <strong>and</strong> Research ................................. 4-80<br />

4.5 Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Environment .................................................................................... 4-82<br />

4.5.1 L<strong>and</strong> Use ..................................................................................................................... 4-82<br />

4.5.1.1 Current Uses on the Refuge ........................................................................... 4-82<br />

4.5.1.2 Surrounding L<strong>and</strong> Uses .................................................................................. 4-84<br />

4.5.2 Public Safety ............................................................................................................... 4-87<br />

4.5.3 Traffic Circulation ...................................................................................................... 4-87<br />

4.5.4 Public Utilities/Easements ....................................................................................... 4-88<br />

4.5.5 Vectors <strong>and</strong> Odors ...................................................................................................... 4-88<br />

4.5.6 Economics/Employment ........................................................................................... 4-88<br />

4.5.7 Environmental Justice .............................................................................................. 4-89<br />

Chapter 5 – Environmental Consequences ..................................................................... 5-1<br />

5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5-1<br />

5.2 Effects to the Physical Environment .................................................................................. 5-1<br />

iv Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Table of Contents<br />

5.2.1 Alternative A -- No Action .......................................................................................... 5-3<br />

5.2.1.1 Effects to Topography/Visual Quality ............................................................. 5-3<br />

5.2.1.2 Effects to Geology/Soils ..................................................................................... 5-3<br />

5.2.1.3 Effects on Mineral Resources ........................................................................... 5-4<br />

5.2.1.4 Effects to Agricultural Resources .................................................................... 5-4<br />

5.2.1.5 Effects to Hydrology .......................................................................................... 5-4<br />

5.2.1.6 Effects to Water Quality .................................................................................... 5-4<br />

5.2.1.7 Effects from Climate Change/Sea Level Rise ................................................ 5-7<br />

5.2.1.8 Effects to Air Quality ......................................................................................... 5-9<br />

5.2.1.9 Effects Related to Greenhouse Gas Emissions ............................................ 5-10<br />

5.2.1.10Effects to Related to Contaminants ............................................................... 5-11<br />

5.2.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-12<br />

5.2.2.1 Effects to Topography/Visual Quality ........................................................... 5-12<br />

5.2.2.2 Effects to Geology/Soils ................................................................................... 5-13<br />

5.2.2.3 Effects to on Mineral Resources .................................................................... 5-14<br />

5.2.2.4 Effects to Agricultural Resources .................................................................. 5-14<br />

5.2.2.5 Effects to Hydrology ........................................................................................ 5-14<br />

5.2.2.6 Effects to Water Quality .................................................................................. 5-16<br />

5.2.2.7 Effects from Climate Change/Sea Level Rise .............................................. 5-21<br />

5.2.2.8 Effects to Air Quality ....................................................................................... 5-21<br />

5.2.2.9 Effects Related to Greenhouse Gas Emissions ............................................ 5-24<br />

5.2.2.10Effects Related to Contaminants ................................................................... 5-24<br />

5.2.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation ................................................... 5-25<br />

5.2.3.1 Effects to Topography/Visual Quality ........................................................... 5-25<br />

5.2.3.2 Effects to Geology/Soils ................................................................................... 5-26<br />

5.2.3.3 Effects on Mineral Resources ......................................................................... 5-27<br />

5.2.3.4 Effects to Agricultural Resources .................................................................. 5-27<br />

5.2.3.5 Effects to Hydrology ........................................................................................ 5-27<br />

5.2.3.6 Effects to Water Quality .................................................................................. 5-27<br />

5.2.3.7 Effects from Climate Change/Sea Level Rise .............................................. 5-28<br />

5.2.3.8 Effects to Air Quality ....................................................................................... 5-28<br />

5.2.3.9 Effects Related to Greenhouse Gas Emissions ............................................ 5-29<br />

5.2.3.10Effects to Related to Contaminants ............................................................... 5-30<br />

5.3 Effects to Habitat <strong>and</strong> Vegetation Resources .................................................................. 5-30<br />

5.3.1 Alternative A -- No Action ........................................................................................ 5-30<br />

5.3.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-33<br />

5.3.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation ................................................... 5-36<br />

5.4 Effects to <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fish</strong>eries ........................................................................................ 5-37<br />

5.4.1 Alternative A -- No Action ........................................................................................ 5-38<br />

5.4.1.1 Effects to Waterfowl, Seabirds, Shorebirds <strong>and</strong> Other Waterbirds ......... 5-38<br />

5.4.1.2 Effects to L<strong>and</strong>birds ........................................................................................ 5-40<br />

5.4.1.3 Effects to <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> Other Marine Organisms .............................................. 5-41<br />

5.4.1.4 Effects to Terrestrial Invertebrates, Amphibians, <strong>and</strong> Reptiles .............. 5-42<br />

5.4.1.5 Effects to Mammals ......................................................................................... 5-43<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment v

Table of Contents <br />

5.4.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-44<br />

5.4.2.1 Effects to Waterfowl, Seabirds, Shorebirds <strong>and</strong> Other Waterbirds ......... 5-44<br />

5.4.2.2 Effects to L<strong>and</strong>birds ........................................................................................ 5-46<br />

5.4.2.3 Effects to <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> Other Marine Organisms .............................................. 5-47<br />

5.4.2.4 Effects to Terrestrial Invertebrates, Amphibians, <strong>and</strong> Reptiles .............. 5-48<br />

5.4.2.5 Effects to Mammals ......................................................................................... 5-50<br />

5.4.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation .................................................. 5-51<br />

5.4.3.1 Effects to Waterfowl, Seabirds, Shorebirds <strong>and</strong> Other Waterbirds ......... 5-51<br />

5.4.3.2 Effects to L<strong>and</strong>birds ........................................................................................ 5-52<br />

5.4.3.3 Effects to <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> Other Marine Organisms .............................................. 5-53<br />

5.4.3.4 Effects to Terrestrial Invertebrates, Amphibians, <strong>and</strong> Reptiles .............. 5-53<br />

5.4.3.5 Effects to Mammals ......................................................................................... 5-54<br />

5.5 Effects to Endangered <strong>and</strong> Threatened Species <strong>and</strong> Other Species of Concern ....... 5-54<br />

5.5.1 Alternative A -- No Action ........................................................................................ 5-55<br />

5.5.1.1 Effects to California Least Tern .................................................................... 5-55<br />

5.5.1.2 Effects to Light-footed Clapper Rail ............................................................. 5-57<br />

5.5.1.3 Effects to Western Snowy Plover .................................................................. 5-57<br />

5.5.1.4 Effects to Salt Marsh Bird’s-Beak ................................................................. 5-58<br />

5.5.1.5 Effects to Pacific Green Sea Turtle ............................................................... 5-58<br />

5.5.1.6 Effects to Belding’s Savannah Sparrow ........................................................ 5-59<br />

5.5.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-59<br />

5.5.2.1 Effects to California Least Tern .................................................................... 5-59<br />

5.5.2.2 Effects to Light-footed Clapper Rail ............................................................. 5-60<br />

5.5.2.3 Effects to Western Snowy Plover .................................................................. 5-61<br />

5.5.2.4 Effects to Salt Marsh Bird’s-Beak ................................................................. 5-61<br />

5.5.2.5 Effects to Pacific Green Sea Turtle………………………………………..5-61<br />

5.5.2.6 Effects to Belding’s Savannah Sparrow ........................................................ 5-62<br />

5.5.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation .................................................. 5-63<br />

5.5.3.1 Effects to California Least Tern .................................................................... 5-63<br />

5.5.3.2 Effects to Light-footed Clapper Rail ............................................................. 5-63<br />

5.5.3.3 Effects to Western Snowy Plover .................................................................. 5-64<br />

5.5.3.4 Effects to Salt Marsh Bird’s-Beak ................................................................. 5-65<br />

5.5.3.5 Effects to Pacific Green Sea Turtle ............................................................... 5-65<br />

5.5.3.6 Effects to Belding’s Savannah Sparrow ........................................................ 5-65<br />

5.6 Effects to Cultural Resources ............................................................................................ 5-66<br />

5.6.1 Alternative A -- No Action ........................................................................................ 5-68<br />

5.6.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-69<br />

5.6.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation .................................................. 5-70<br />

5.7 Effects to the Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Environment ........................................................... 5-71<br />

5.7.1 Alternative A -- No Action ........................................................................................ 5-73<br />

5.7.1.1 Effects to L<strong>and</strong> Use ......................................................................................... 5-73<br />

5.7.1.2 Effects Related to Public Safety .................................................................... 5-73<br />

vi Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Table of Contents<br />

5.7.1.3 Effects to Traffic Circulation .......................................................................... 5-74<br />

5.7.1.4 Effects to Public Utilities/Easements ........................................................... 5-74<br />

5.7.1.5 Effects Related to Vectors <strong>and</strong> Odors ........................................................... 5-74<br />

5.7.1.6 Effects to Economics/Employment ............................................................... 5-75<br />

5.7.1.7 Effects to Environmental Justice ................................................................... 5-76<br />

5.7.2 Alternative B – Maximize Salt Marsh Restoration, Continue Current<br />

Public Uses .................................................................................................................. 5-76<br />

5.7.2.1 Effects to L<strong>and</strong> Use ......................................................................................... 5-76<br />

5.7.2.2 Effects Related to Public Safety .................................................................... 5-76<br />

5.7.2.3 Effects to Traffic Circulation .......................................................................... 5-77<br />

5.7.2.4 Effects to Public Utilities/Easements ........................................................... 5-77<br />

5.7.2.5 Effects Related to Vectors <strong>and</strong> Odors ........................................................... 5-77<br />

5.7.2.6 Effects to Economics/Employment ............................................................... 5-78<br />

5.7.2.7 Effects to Environmental Justice ................................................................... 5-78<br />

5.7.3 Alternative C (Proposed Action) – Optimize Upl<strong>and</strong>/Wetl<strong>and</strong> Restoration,<br />

Improve Opportunities for <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation ................................................... 5-78<br />

5.7.3.1 Effects to L<strong>and</strong> Use ......................................................................................... 5-78<br />

5.7.3.2 Effects Related to Public Safety .................................................................... 5-79<br />

5.7.3.3 Effects to Traffic Circulation .......................................................................... 5-79<br />

5.7.3.4 Effects to Public Utilities/Easements ........................................................... 5-79<br />

5.7.3.5 Effects Related to Vectors <strong>and</strong> Odors ........................................................... 5-80<br />

5.7.3.6 Effects to Economics/Employment ............................................................... 5-80<br />

5.7.3.7 Effects to Environmental Justice ................................................................... 5-80<br />

5.8 Indian Tribal Assets ............................................................................................................. 5-80<br />

5.9 Cumulative Effects ............................................................................................................... 5-81<br />

5.9.1 Cumulative Effects to the Physical Environment ................................................. 5-84<br />

5.9.2 Cumulative Effects to Biological Resources .......................................................... 5-85<br />

5.9.3 Cumulative Effects to Cultural Resources ............................................................. 5-85<br />

5.9.4 Cumulative Effects to the Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Environment ............................ 5-85<br />

5.10 Summary of Effects ............................................................................................................. 5-86<br />

Chapter 6 - Implementation ............................................................................................... 6-1<br />

6.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 6-1<br />

6.2 Refuge Goals, Objectives <strong>and</strong> Strategies ............................................................................ 6-2<br />

Goal 1 .............................................................................................................................. 6-2<br />

Goal 2 .............................................................................................................................. 6-8<br />

Goal 3 ............................................................................................................................ 6-14<br />

Goal 4 ............................................................................................................................ 6-18<br />

6.3 Monitoring ............................................................................................................................. 6-18<br />

6.4 Adaptive Management ......................................................................................................... 6-19<br />

6.5 Partnership Opportunities .................................................................................................. 6-19<br />

6.6 Step-down Plans ................................................................................................................... 6-20<br />

6.6.1 Draft Step-Down Plans.............................................................................................. 6-21<br />

Draft Integrated Pest Management Plan ........................................................ 6-21<br />

Draft Mosquito Management Plan .................................................................... 6-21<br />

6.7 Compliance Requirements .................................................................................................. 6-23<br />

6.7.1 Federal Regulations, Executive Orders, <strong>and</strong> Legislative Acts ........................... 6-23<br />

Human Rights Regulations ................................................................................ 6-23<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment vii

Table of Contents ───────────────────────────────────────────<br />

Cultural Resources Regulations ....................................................................... 6-23<br />

Biological Resources Regulations ..................................................................... 6-24<br />

L<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Water Use Regulations ..................................................................... 6-24<br />

Tribal Coordination ............................................................................................. 6-25<br />

Wilderness Review .............................................................................................. 6-25<br />

6.7.2 Potential Future Permit, Approval, <strong>and</strong>/or Review Requirements .................... 6-26<br />

6.7.3 Conservation Measures to be Incorporated into Future Projects ...................... 6-27<br />

6.8 Refuge Operations ............................................................................................................... 6-28<br />

6.8.1 Funding <strong>and</strong> Staffing ................................................................................................. 6-29<br />

Current <strong>and</strong> Future Staffing Needs ................................................................. 6-32<br />

Potential Funding Sources for Implementing CCP Projects ....................... 6-33<br />

6.8.2 Compatibility/Appropriate Use Determinations ................................................... 6-33<br />

Chapter 7 – References Cited ............................................................................................. 7-1<br />

Appendices<br />

Appendix A. Compatibility Determinations (draft)<br />

A-1 <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation, Interpretation, <strong>and</strong> Environmental Education<br />

A-2 Scientific Research (with accompanying Finding of Appropriateness)<br />

A-3 Mosquito Management (with accompanying Finding of Appropriateness)<br />

Appendix B. List of Preparers, Planning Team Members, <strong>and</strong> Persons/Agencies Consulted<br />

Appendix C. Integrated Pest Management Program (draft)<br />

Appendix D. Mosquito Management Plan (draft)<br />

Appendix E. Federal <strong>and</strong> State Ambient Air Quality St<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

Appendix F. Species Lists<br />

Appendix G. Fire Management Plan Exemption<br />

Appendix H. Wilderness Inventory<br />

Appendix I. Request of Cultural Resource Compliance Form<br />

Appendix J. Glossary of Terms<br />

Appendix K. Distribution List<br />

List of Figures<br />

1-1 Regional Vicinity Map for the Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ............................. 1-2<br />

1-2 Location Map .......................................................................................................................... 1-3<br />

1-3 Artist's Rendition of Proposed Freeway Bisecting Anaheim Marsh ........................... 1-16<br />

2-1 Comprehensive Conservation Planning Process ............................................................... 2-2<br />

3-1 Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge Site Map ................................................................. 3-2<br />

3-2 Alternative A ........................................................................................................................ 3-12<br />

3-3 Approved Mosquito Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Control Areas ...................................................... 3-22<br />

3-4 Alternative B......................................................................................................................... 3-24<br />

3-5 Alternative C ......................................................................................................................... 3-35<br />

4-1 Seal Beach NWR Site Map ................................................................................................... 4-2<br />

4-2 Historical (1894) Coastal Wetl<strong>and</strong>s of Los Angeles <strong>and</strong> Orange Counties.................... 4-4<br />

4-3 Historical (1875) Wetl<strong>and</strong>s of Anaheim Bay ...................................................................... 4-5<br />

4-4 Aerial View of Anaheim Bay <strong>and</strong> Salt Marsh Complex in 1922 ...................................... 4-6<br />

4-5 Comparison of Anaheim Bay in 1873 <strong>and</strong> 1976 .................................................................. 4-7<br />

viii Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ────────────────────────────────

─────────────────────────────────────────── Table of Contents<br />

4-6 Oblique Aerial View of the Seal Beach NWR, Anaheim Bay, Northern Orange County<br />

<strong>and</strong> Distant Santa Ana Mountains ................................................................................ 4-9<br />

4-7 USGS Topographic Map of Refuge ................................................................................... 4-10<br />

4-8 Steep, Scoured Bank at NE Corner of Kitts-Bolsa Cell ................................................ 4-11<br />

4-9 Soils Map ............................................................................................................................... 4-12<br />

4-10 Anaheim Bay-Huntington Harbour Watershed .............................................................. 4-16<br />

4-11 Tidal <strong>and</strong> Freshwater Conveyance Points ........................................................................ 4-18<br />

4-12 Installation Restoration Program Sites in Proximity to Seal Beach NWR ................. 4-35<br />

4-13 Habitats Types on the Seal Beach NWR .......................................................................... 4-43<br />

4-14 Light-footed Clapper Rail Counts on Seal Beach NWR, 1980-2005 ............................. 4-65<br />

4-15 Areas of Previous Archaeological Surveys at Seal Beach NWR ................................... 4-81<br />

4-16 L<strong>and</strong> Use in the Vicinity of Seal Beach NWR ................................................................. 4-86<br />

List of Tables<br />

3-1 Current Pesticide Use Information for the Seal Beach NWR………………………..3-26<br />

3-2 OCVCD Criteria for Considering Pesticide Application to Control Immature Mosquito<br />

Populations ..................................................................................................................... 3-26<br />

3-3 OCVCD Criteria for Considering Adulticide Application .............................................. 3-27<br />

3-4 Habitat Restoration Proposals for Alternative B……………………………………...3-31<br />

3-5 Habitat Restoration Proposals for Alternative C……………………………………...3-37<br />

3-6 Comparison of Alternatives by Issue…………………………………………………...3-41<br />

4-1 Historical Acreages of Coastal Los Angeles <strong>and</strong> Orange County Wetl<strong>and</strong>s ................. 4-3<br />

4-2 C<strong>and</strong>idate Toxix Hot Spots in <strong>and</strong> around Anaheim Bay ............................................... 4-24<br />

4-3 Water Column Measurements for Three Locations in Anaheim Bay from August 2001<br />

<strong>and</strong> February/April 2003 .............................................................................................. 4-26<br />

4-4 Summary of Installation Restoration Program Sites On <strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Immediately<br />

Surrounding Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge .................................................. 4-36<br />

4-5 Summary of the Habitat Types Occurring on the Seal Beach NWR ........................... 4-42<br />

4-6 Reptiles <strong>and</strong> Amphibians Expected to Occur on NWSSB ............................................. 4-51<br />

4-7 Top Five <strong>Fish</strong> Taxa Collected in Anaheim Bay from September 1990 to July 1995 .. 4-57<br />

4-8 California Least Terns Nesting Results for Seal Beach NWR ..................................... 4-61<br />

4-9 Light-footed Clapper Rail Breeding Pair Estimates for Anaheim Bay ....................... 4-65<br />

4-10 Belding’s Savannah Sparrow Territories at Seal Beach NWR ..................................... 4-71<br />

4-11 Birds of Conservation Concern on <strong>and</strong> adjacent to the Seal Beach NWR .................. 4-72<br />

4-12 California Special Status Species Observed or with the Potential to Occur on the<br />

Seal Beach NWR ........................................................................................................... 4-74<br />

4-13 Annual Visitation to Seal Beach NWR .............................................................................. 4-84<br />

4-14 Refuge Visits Associated with Special Events ................................................................. 4-84<br />

4-15 Economic/Employment Data for Orange County, California ........................................ 4-90<br />

4-16 Seal Beach NWR Staff <strong>and</strong> Budget (Estimate Based on FY2008) ............................... 4-90<br />

4-17 Census Data for Areas in Proximity to Seal Beach NWR ............................................. 4-91<br />

5-1 Scenarios Used to Run SLAMM 5 ....................................................................................... 5-8<br />

5-2 Environmental Fate of Herbicides Used on the Refuge………………………………5-19<br />

5-3 Estimated Visitation <strong>and</strong> Expenditures for the Seal Beach NWR in 2006………...... 5-75<br />

5-4 Economic Impacts from Seal Beach NWR Visitation in 2006 ....................................... 5-76<br />

5-5 Summary of Potential Effects of Implementing Alternatives A, B, or C .................... 5-86<br />

6-1 Step-down Plans Proposed for the Seal Beach NWR……………………………........6-20<br />

─────────────── Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment ix

Table of Contents ───────────────────────────────────────────<br />

6-2 Proposed Update to the SAMMS Database………...... .................................................. 6-30<br />

6-3 Proposed Update to the RONS Database ........................................................................ 6-31<br />

6-4 Estimated Staffing Needs to Fully Implement the Seal Beach NWRP ...................... 6-32<br />

x Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ────────────────────────────────

1 Introduction<br />

1.1 Introduction<br />

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge (NWR or Refuge) encompasses approximately 965 acres of<br />

coastal wetl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> upl<strong>and</strong>s in northwestern Orange County, California (see Figure 1-1). The<br />

Refuge, which is managed by the U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong> (<strong>Service</strong>) as part of the National<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System (NWRS), is located entirely within the boundaries of Naval Weapons<br />

Station Seal Beach (NWSSB) (Figure 1-2). The tidally influenced wetl<strong>and</strong> habitat protected<br />

within the Refuge supports thous<strong>and</strong>s of migratory birds that travel along the Pacific Flyway <strong>and</strong><br />

provides habitat for listed species including the California least tern (Sternula antillarum browni)<br />

<strong>and</strong> light-footed clapper rail (Rallus longirostris levipes), both of which nest on the Refuge.<br />

This Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) has been prepared to describe the desired future<br />

conditions of the Seal Beach NWR. It is also intended to provide long-range guidance <strong>and</strong><br />

management direction to achieve the purposes for which the Refuge was established; to help fulfill<br />

the mission of the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System; to maintain <strong>and</strong>, where appropriate, restore<br />

the ecological integrity of the Refuge <strong>and</strong> the Refuge System; <strong>and</strong> to meet other m<strong>and</strong>ates.<br />

1.2 Purpose <strong>and</strong> Need for the Plan<br />

The purpose <strong>and</strong> need for the Seal Beach NWR CCP is to provide guidance to the Refuge Manager<br />

<strong>and</strong> others for how this Refuge should be managed to best achieve the purposes for which it was<br />

established <strong>and</strong> to contribute to the mission of the NWRS. The CCP when completed is intended<br />

to provide a 15-year management plan for addressing the conservation of fish, wildlife, <strong>and</strong> plant<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> their related habitats, while also presenting the opportunities on the Refuge for<br />

compatible wildlife-dependent recreational uses. It is through the CCP process that the<br />

overarching wildlife, public use, <strong>and</strong>/or management needs for the Refuge, as well as any issues<br />

affecting the management of Refuge resources <strong>and</strong> public use programs, are identified; <strong>and</strong><br />

various strategies for meeting Refuge needs <strong>and</strong>/or resolving issues that may be impeding the<br />

achievement of Refuge purposes are evaluated <strong>and</strong> ultimately presented for implementation.<br />

The CCP is intended to:<br />

Ensure that Refuge management is consistent with the NWRS mission <strong>and</strong> Refuge<br />

purposes <strong>and</strong> that the needs of wildlife come first, before other uses;<br />

Provide a scientific foundation for Refuge management;<br />

Establish a clear vision statement of the desired future conditions for Refuge habitat,<br />

wildlife, other species, visitor services, staffing, <strong>and</strong> facilities;<br />

Communicate the <strong>Service</strong>’s management priorities for the Refuge to its neighbors, visitors,<br />

partners, state, local, <strong>and</strong> other Federal agencies, <strong>and</strong> to the general public;<br />

Ensure that current <strong>and</strong> future uses of the Refuge are compatible with Refuge purposes;<br />

Provide long-term continuity in Refuge management; <strong>and</strong><br />

Provide a basis for budget requests to support the Refuge’s needs for staffing, operations,<br />

maintenance, <strong>and</strong> capital improvements.<br />

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan/Environmental Assessment 1-1

Ventura<br />

County<br />

Hopper Mt. NWR<br />

P a c i f i c<br />

O c e a n<br />

Legend<br />

^_ Seal Beach NWR<br />

Other NWR<br />

§¨¦<br />

County Seat<br />

U.S. Interstate<br />

County Boundary<br />

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Regional Location, Southern California<br />

§¨¦ 5<br />

S a n t a<br />

M onica<br />

B a y<br />

Kern County<br />

§¨¦ 405<br />

Seal Beach NWR<br />

Santa Catalina Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

San Clemente Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

Los Angeles<br />

County<br />

§¨¦ 210<br />

Los Angeles<br />

¯<br />

^_<br />

Santa Ana<br />

0 10 20 30 40 Miles<br />

§¨¦ 10<br />

Orange<br />

County<br />

§¨¦ 5<br />

§¨¦ 15<br />

§¨¦ 15<br />

San Bernardino<br />

County<br />

San Bernardino<br />

Riverside<br />

§¨¦ 5<br />

San Diego<br />

San Diego Bay NWR<br />

Tijuana Slough NWR<br />

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

California<br />

§¨¦ 15<br />

Nevada<br />

Seal Beach NWR<br />

^_<br />

Riverside<br />

County<br />

San Diego<br />

NWR<br />

San Diego<br />

County<br />

§¨¦ 8<br />

M e x i c o<br />

Utah<br />

Arizona<br />

Figure 1-1. Regional Vicinity Map for the Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Figure 1-1. Regional Vicinity Map of Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge

Los Angeles<br />

County<br />

Long Beach Harbor<br />

California<br />

Nevada<br />

Seal Beach NWR<br />

^_<br />

¯<br />

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

Refuge Location, Los Angeles/Long Beach/Santa Ana Metro Area<br />

Los Angeles<br />

River<br />

Utah<br />

Arizona<br />

0 1 2 3 4Miles<br />

Long Beach<br />

San Pedro Bay<br />

Legend<br />

§¨¦<br />

!(<br />

1<br />

Los<br />

Cerritos<br />

Wetl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Seal Beach NWR<br />

San Gabriel<br />

River<br />

Anaheim Bay<br />

Seal<br />

Beach<br />

Huntington Harbour<br />

Naval Weapons Station<br />

Seal Beach<br />

City<br />

U.S. Interstate<br />

State Highway<br />

County Boundary<br />

Naval<br />

Weapons<br />

Station<br />

Seal Beach<br />

Seal<br />

Beach<br />

NWR<br />

Bolsa<br />

Chica<br />

Wetl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Bolsa Chica State Beach<br />

Pacific<br />

Ocean<br />

Figure 1-2. Location Map Mapof<br />

Seal Beach National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

Westminster<br />

Huntington Beach<br />

1<br />

§¨¦ 405<br />

Huntington<br />

State Beach<br />

Garden Grove<br />

22<br />

Newport Bay<br />

Orange<br />

County<br />

Fountain Valley<br />

Costa Mesa<br />

55<br />

Santa<br />

Ana<br />

73<br />

Newport Beach

Chapter 1 <br />

The development of this CCP is also required to fulfill legislative obligations of the <strong>Service</strong>. Its<br />

preparation is m<strong>and</strong>ated by the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, as<br />

amended by the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 (the Improvement<br />

Act) (Public Law 105-57). The Improvement Act requires that a CCP be prepared for each refuge<br />