T. Heilbron 2012.Botanical relics of the plantations - osodresie

T. Heilbron 2012.Botanical relics of the plantations - osodresie

T. Heilbron 2012.Botanical relics of the plantations - osodresie

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Botanical Relics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plantations <strong>of</strong><br />

Suriname<br />

Author:<br />

Thiëmo HEILBRON<br />

MSc Thesis<br />

November 23, 2012<br />

Supervisor:<br />

Dr. Tinde VAN ANDEL

Abstract<br />

This research demonstrates <strong>the</strong> need for recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation<br />

era in Suriname among scientists, Surinamese citizens and tourists, in order to ensure<br />

its protection as a living memory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s turbulent history. The botanical heritage<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation society was investigated by searching for physical relic plants and exploring<br />

<strong>the</strong> local knowledge about <strong>the</strong>se plants, also an important aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>plantations</strong>. On 27 locations <strong>of</strong> former <strong>plantations</strong>, 41 specimens <strong>of</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong> were<br />

collected. Individuals <strong>of</strong> 18 species could be regarded as plantation <strong>relics</strong>. Field assessment,<br />

interviews with <strong>the</strong> local population and landowners, historical literature, maps and pictures<br />

were essential to placing <strong>the</strong> <strong>relics</strong> into context. A former production field <strong>of</strong> cacao dating<br />

to pre-abolition times, remnants <strong>of</strong> tamarind lanes, a date palm from Africa that became<br />

a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural vegetation, a banana used as a food source by slaves in <strong>the</strong>ir escape<br />

from <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>, remnants <strong>of</strong> cactus hedges in <strong>the</strong> forest, a shade tree for cash crops<br />

still very common, a Javanese black rice variety in decline, wild hedge plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genus<br />

Triphasia and a wild banana, a new record for Suriname, were amongst <strong>the</strong> finds. Results<br />

<strong>of</strong> this study will be incorporated in a botanical heritage project for tourists on one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

research locations at plantation Reijnsdorp, Commewijne.<br />

1

Contents<br />

1 Introduction 3<br />

1.1 Plantations and <strong>the</strong>ir plants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

1.2 Suriname . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

1.2.1 Topography and history . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

1.2.2 Legacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plantations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

1.2.3 Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plantations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

1.3 Key Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

2 Methodology 7<br />

3 Results 9<br />

3.1 Graphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<br />

3.2 Detailed examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

3.2.1 Amerindian <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

3.2.2 Cash crop <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

3.2.3 Plantation structure <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

3.2.4 Plantation owner garden <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

3.2.5 Slave garden <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

3.2.6 Wage laborer <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

4 Discussion 15<br />

4.1 Plantations in Suriname and diversity in <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

4.2 Complications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15<br />

4.3 Relics in context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

4.4 Tracking plants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

4.5 Prospects <strong>of</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

4.6 Follow-up research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

5 Conclusion 18<br />

6 Acknowledgements 19<br />

A List <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collected species 24<br />

2

1 Introduction<br />

1.1 Plantations and <strong>the</strong>ir plants<br />

The formation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colonial plantation economy system based on slave labor in <strong>the</strong> New World<br />

and <strong>the</strong> subsequent increased Atlantic travel not only set in motion <strong>the</strong> forced and voluntary<br />

migration <strong>of</strong> large numbers <strong>of</strong> people, but also <strong>the</strong> dispersal <strong>of</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> plant species (Carney,<br />

2005; Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f, 2009; Morgan, 1997; Schiebinger, 2004). Several crops made <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

way to <strong>the</strong> Americas from o<strong>the</strong>r regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, such as c<strong>of</strong>fee (C<strong>of</strong>fea spp.) from Africa<br />

and banana (Musa spp.) domesticated since long in Africa from Asia (Mbida et al., 2000),<br />

sugarcane (Saccharum <strong>of</strong>ficinarum L.) and citrus (Citrus spp.) from Asia, and cabbage (Brassica<br />

spp.) from Europe (Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f, 2009; Voeks, 2013; Herlein, 1718; Van Andel et al.,<br />

2012).<br />

The recent interest in studying plant dispersal <strong>of</strong> enslaved Africans in <strong>the</strong> historical context<br />

<strong>of</strong> slavery and <strong>plantations</strong> has revealed a vivid image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plant use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

slaves, slave owners and <strong>the</strong> indigenous population (Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f, 2009; Voeks, 2013;<br />

Mann, 2011; Carney, 2004). By studying dispersal tracks and uses <strong>of</strong> plants in <strong>the</strong> plantation era,<br />

ethnobotanists have shown how slaves and slave-owners planted (or managed) different plants<br />

for a certain rationale. Whilst slave owners had interest in planting cash crops for trade, slaves<br />

grew <strong>the</strong>ir plants for medicinal, food and ritual use in <strong>the</strong>ir own gardens (Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f,<br />

2009; Van Andel et al., 2012; Carney, 2005, 2002).<br />

There is a vast body <strong>of</strong> information available on African diaspora, slavery and <strong>plantations</strong>,<br />

from archaeological and historical research (e.g. Orser & Funari, 2001; Klingelh<strong>of</strong>er, 1987;<br />

Singleton, 1995; Pryor, 1982). However, little research has been done on plants in a historical<br />

context. Studying <strong>the</strong> plants used by <strong>the</strong> slaves and slave owners will provide information on<br />

<strong>the</strong>se people and <strong>the</strong>ir history.<br />

1.2 Suriname<br />

1.2.1 Topography and history<br />

The former Dutch colony <strong>of</strong> Suriname is situated in <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn part <strong>of</strong> South-America, and<br />

bordered by Guyana to <strong>the</strong> West, French Guyana to <strong>the</strong> East, Brazil to <strong>the</strong> South and <strong>the</strong> Atlantic<br />

Ocean to <strong>the</strong> North (See: Fig. 3). The country lies roughly between 6 ◦ and 2 ◦ Nor<strong>the</strong>rn latitude<br />

and 58 ◦ and 54 ◦ Western longitude. Owing to its geographical position close to <strong>the</strong> equator<br />

Suriname has a tropical rainforest and tropical monsoon climate (respectively Af and Am in <strong>the</strong><br />

Köppen-Geiger climate classification (Peel et al., 2007)), with temperature averaging around<br />

26 ◦ C and annual precipitation between 2000-2400mm. The soil <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coastal area consists <strong>of</strong><br />

sea clay with local sand and shell ridges. The coastal vegetation types are, from North to South,<br />

mangrove forest, swamp with herbs and shrubs, and swamp woods. In <strong>the</strong> country’s interior,<br />

a variety <strong>of</strong> rainforest types exists. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> country occupies a central position in <strong>the</strong><br />

floral district <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas (Lindeman & Moolenaar, 1953).<br />

Around 1650, English settlers established <strong>the</strong> first <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname, producing<br />

mostly sugarcane (Saccharum <strong>of</strong>ficinarum ) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) (Wolbers, 1861;<br />

Van Lier, 1977). In 1667, <strong>the</strong> Dutch, at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Second Anglo-Dutch war, conquered <strong>the</strong><br />

3

small but prospering colony (Wolbers, 1861). The Dutch expanded <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong><br />

and <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> cash crops. The best locations for <strong>plantations</strong> were <strong>the</strong> fertile coastal areas,<br />

where present vegetation could be cleared and areas could be transformed to fertile arable land<br />

by implementing a drainage system with canals and sluices. Large numbers <strong>of</strong> enslaved people<br />

from <strong>the</strong> African continent were shipped to Suriname to work on <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>.<br />

After periods <strong>of</strong> prosperity and hardship for <strong>the</strong> colony, by 1770 Suriname eventually<br />

gave rise to over 400 <strong>plantations</strong> (Hoefte, 1996) (See: Fig. 1). The main crops in production<br />

on <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> were sugarcane (Saccharum <strong>of</strong>ficinarum), cacao (Theobroma cacao), cotton<br />

(Gossypium barbadense), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and indigo (Indig<strong>of</strong>era tinctoria) (<strong>Heilbron</strong>,<br />

1993). The plantation system in Suriname eventually declined due to increased pressure<br />

from competition on <strong>the</strong> world market and raids by maroons (<strong>Heilbron</strong>, 1993; Benjamins &<br />

Snelleman, 1914).<br />

Figure 1: Map showing <strong>the</strong> many <strong>plantations</strong> in coastal Suriname (Moseberg, 1801)<br />

In 1863 slavery was abolished in Suriname, but former slaves were forced to work under<br />

indentured contracts for a ten-year period (Emmer, 1993). After this period, large numbers <strong>of</strong><br />

former slaves left <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> for cities and villages. To provide workforce for <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>,<br />

contract laborers were recruited from o<strong>the</strong>r areas, mostly from <strong>the</strong> former British East-Indies,<br />

former Dutch East-Indies (Java) and China (Van Lier, 1977; Benjamins & Snelleman, 1914). In<br />

<strong>the</strong> period that followed, <strong>the</strong> plantation economy gradually collapsed and estates were overtaken<br />

by small farmers or abandoned (<strong>Heilbron</strong>, 1982). Currently, <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> is still<br />

abandoned and have been overgrown by natural vegetation, while o<strong>the</strong>rs, especially around <strong>the</strong><br />

capital <strong>of</strong> Suriname, Paramaribo, have been urbanized. Along <strong>the</strong> Commewijne and Suriname<br />

rivers, many areas are still known by <strong>the</strong>ir historical plantation name.<br />

4

(a) Satellite image <strong>of</strong> abandoned<br />

and overgrown <strong>plantations</strong>,<br />

Warappa creek, Commewijne<br />

1.2.2 Legacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plantations<br />

(b) An historical planter’s house<br />

on partly urbanized plantation Alliance,<br />

Commewijne<br />

Figure 2: Remnants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname<br />

(c) A kettle for boiling sugarcane<br />

syrup in <strong>the</strong> forest on plantation<br />

de Hoop, Commewijne<br />

In Suriname plantation history is still very well visible, both in abandoned and urbanized areas<br />

(See: Fig. 2). Remnants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extensive coastal drainage system are visible on satellite images<br />

(2a), while on some former <strong>plantations</strong> <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> buildings (2b) and various o<strong>the</strong>r remnants<br />

and artifacts can be found (2c). Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, names like ‘Blauwgrond’ (Blueground in Dutch)<br />

for a former indigo plantation refer to historical links.<br />

There is growing interest in Suriname for conserving, protecting and restoring <strong>plantations</strong><br />

for educational and heritage tourism purposes. Organizations like Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Protection<br />

<strong>of</strong> Antiquities Suriname (STIBOSUR), The Built Heritage Foundation Suriname (SGES)<br />

and restoration projects on former <strong>plantations</strong> Reijnsdorp (http://www.warappakreek.com),<br />

Peperpot (http://plantagepeperpot.nl) and Frederiksdorp (http://www.frederiksdorp.<br />

com) are examples <strong>of</strong> this.<br />

Most archaeological research in Suriname has focused on <strong>the</strong> indigenous population (e.g.<br />

Versteeg, 1998, 1992). Little research on <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> and plantation era (roughly 1667-1873)<br />

has taken place. One exception is <strong>the</strong> search for fort Buku, <strong>the</strong> stronghold <strong>of</strong> Boni, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

most famous maroons fighting against colonial authority in Suriname (Pel et al., 2008). Still, no<br />

scientific research has been done on <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation society.<br />

1.2.3 Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plantations<br />

There are a limited number <strong>of</strong> 17 th and 18 th century historical accounts that provide some information<br />

on <strong>the</strong> plants present on <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname. Important are <strong>the</strong> recently rediscovered<br />

diary <strong>of</strong> Linnaeus-trained botanist Daniel Rolander, who mentioned plants from <strong>the</strong><br />

gardens <strong>of</strong> slaves, such as Cleome gynandra L. used as a vegetable and Croton tiglium L. used<br />

medicinally (Rolander, 2008). O<strong>the</strong>r sources are <strong>the</strong> drawings <strong>of</strong> Maria Sibylla Merian (1705),<br />

<strong>the</strong> collections <strong>of</strong> Gustav Dahlberg (1771), <strong>the</strong> Hermann herbarium (Van Andel et al., in press)<br />

and historical descriptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colony (Herlein, 1718; Fermin, 1765; Hartsinck, 1770). Apart<br />

from obvious cash crops, African crops were brought as ‘local known’ food for <strong>the</strong> slaves as<br />

provisions on <strong>the</strong> Trans-Atlantic journey (Emmer, 2007). The more recent literature that covers<br />

plantation crops in Suriname dates from <strong>the</strong> 1960s (e.g. Ostendorf, 1962; Wessels Boer, 1965).<br />

5

The potential contribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> slave population on <strong>the</strong> plants present on <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>,<br />

should not be underestimated. In <strong>the</strong> period until <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery around 300.000 to<br />

350.000 Africans, mostly from Guinea and Congo, but also Cameroon, Angola, Togo and Senegal,<br />

were brought to Suriname (Van Lier, 1977). Slave ships were <strong>the</strong> vessels for a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

seeds and plants from Africa(Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f, 2009). Slaves constituted a significant proportion<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population in <strong>the</strong> colony, sometimes at a ratio <strong>of</strong> one to 65 on <strong>plantations</strong> and a<br />

ratio <strong>of</strong> two to seven in urban areas in 1787 (Van Lier, 1977; Hoefte, 1996). Many plantation<br />

slaves were allowed to cultivate <strong>the</strong>ir own provision grounds (Emmer, 2007; Price, 1991).<br />

Almost 150 years after <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery in Suriname, part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plantation era is <strong>of</strong> botanical nature. A relic is defined as a ‘survivor or remnant left after decay,<br />

disintegration, or disappearance’ (Merriam-Webster dictionary). In <strong>the</strong> discourse <strong>of</strong> biology, a<br />

relic can be an individual, group <strong>of</strong> individuals (population) or a species that has managed to<br />

survive from an earlier time in an area or population that has undergone considerable changes<br />

(e.g. Mousadik & Petit, 1996; Li et al., 2012). Carney & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f (2009) use <strong>the</strong> term ‘legacy’<br />

to describe African botanical heritage. Here, ‘botanical relic’ is used to refer to a surviving plant<br />

individual introduced by humans to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname and its <strong>of</strong>fspring. These <strong>relics</strong><br />

are <strong>the</strong> heritage <strong>of</strong> a time period that has had significant impact on <strong>the</strong> country’s history. In<br />

addition to <strong>the</strong> physical botanical <strong>relics</strong> <strong>the</strong>mselves, <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> local population on<br />

<strong>the</strong>se <strong>relics</strong> is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colonial history, and is <strong>of</strong> interest as well.<br />

1.3 Key Questions<br />

This study aims to reveal and document <strong>the</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> <strong>of</strong> Suriname. The<br />

questions addressed in this research are:<br />

1. What botanical <strong>relics</strong> can be found on former <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname?<br />

2. Are <strong>the</strong> origin and <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> plant species reflected in <strong>the</strong>ir contemporary uses,<br />

stories and local names?<br />

3. How useful are <strong>the</strong>se botanical <strong>relics</strong> as indicators for <strong>the</strong> former presence <strong>of</strong> a plantation?<br />

This research may contribute to <strong>the</strong> recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation<br />

era, among scientists, Surinamese citizens and tourists, and <strong>the</strong>ir protection as a living memory<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s turbulent history. Findings <strong>of</strong> this research will be incorporated in a project<br />

on botanical heritage named ‘Botanical Legacy Garden’ for educational purposes, at Plantation<br />

Reijnsdorp (http://www.warappakreek.com).<br />

6

2 Methodology<br />

The direct motive for this study was <strong>the</strong> request <strong>of</strong> a Dutch tourist operator who recently started a<br />

project for eco-tourism development on part <strong>of</strong> a plantation (Reijnsdorp, Commewijne district).<br />

He encountered rows <strong>of</strong> cacti and a date palm species in <strong>the</strong> forest and was interested in <strong>the</strong><br />

origin and history <strong>of</strong> those plants.<br />

From literature on plantation crops (e.g Van Andel et al., 2012; Rolander, 2008; Ostendorf,<br />

1962; Stahel, 1944), a list was made <strong>of</strong> plant species that might be expected as <strong>relics</strong> on former<br />

<strong>plantations</strong>. The list included most prominent former cash crops, such as Theobroma cacao and<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fea liberica and plants that supported <strong>the</strong>m, for example Erythrina spp. as a shade tree. Some<br />

species described in historical literature as being planted in slave or slave owners’ gardens, such<br />

as Cleome gynandra and Croton tiglium (Rolander, 2008), Furcraea foetida, and plants which,<br />

according to local inhabitants, might have some historical connection to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>, such<br />

as <strong>the</strong> columnar cactus Cereus spp., were also included. Color images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se species were<br />

provided to local inhabitants to ask whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y knew <strong>the</strong>se species and <strong>the</strong>ir locality.<br />

Fieldwork was performed between March 6 th and May 19 th , 2012. After spending 13<br />

days at plantation Reijnsdorp, new locations were chosen according to information gained from<br />

open-ended interviews with local guides, hunters, fishermen and elderly people. Information<br />

regarding <strong>the</strong> whereabouts <strong>of</strong> possible relic individuals was also obtained, and vernacular names<br />

and stories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se plants were documented. Figure 3 shows <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>plantations</strong> where fieldwork was conducted. Generally, <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> are distributed over five<br />

areas, namely Warappa creek (#1-12), <strong>the</strong> mouth <strong>of</strong> Commewijne river (#13-18), Orleane creek<br />

(#19-21), <strong>the</strong> mouth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Suriname river (#22-25) and <strong>the</strong> lower Suriname river (#26-27) area.<br />

For each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>relics</strong>, a botanical voucher was made using standard botanical techniques. The<br />

plants’ locations were logged in a GPS device. Observations on growth form, reproduction,<br />

abundance and specific patterns on site were made, and pictures were taken <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> locality. For<br />

species encountered various times at different localities, only GPS data were collected. For<br />

cacti collected, <strong>the</strong> alcohol method described by De Groot (2011) was used prior to drying.<br />

Duplicates <strong>of</strong> all collected species were deposited at <strong>the</strong> National Herbarium Suriname (BBS)<br />

and <strong>the</strong> National Herbarium <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands (NHN). Collection and export permits were<br />

obtained from <strong>the</strong> Nature Conservation Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Suriname Forest Service (L.B.B.). For<br />

<strong>the</strong> cacti specimens collected, a separate CITES permit was obtained (permit nr. 12189).<br />

After <strong>the</strong> fieldwork, <strong>the</strong> collected specimens were identified using <strong>the</strong> Flora <strong>of</strong> Suriname,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas and <strong>the</strong> Checklist <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas (Boggan et al., 1997). For<br />

some specimens, specialist botanists were consulted to identify <strong>the</strong> plants to a (sub)species level,<br />

namely P. Maas (NHN) and M. Hakkinen (H) for Musaceae, D. HilleRisLambers for an Oryza<br />

cultivar and M. Nee (NYBG) for Solanaceae. After identification, <strong>the</strong> plants were added to <strong>the</strong><br />

NHN collection. A sample <strong>of</strong> seeds <strong>of</strong> a black Oryza cultivar was sent to <strong>the</strong> Anne van Dijk<br />

Rijst Onderzoekscentrum Nickerie (ADRON) in Suriname for documenting and maintaining<br />

this cultivar. It is currently being grown in Nickerie for comparative research.<br />

Maps were made using ArcGIS 10.0, GPS locations collected during fieldwork, <strong>the</strong> digitized<br />

map <strong>of</strong> Bakhuis et al. (1930), and exported satellite imagery from Google Earth (http:<br />

//earth.google.com). For Phoenix reclinata a distribution map was made with <strong>the</strong> ear-<br />

7

Figure 3: Fieldwork locations<br />

lier mentioned datasets, location data <strong>of</strong> herbarium specimens from <strong>the</strong> NHN collection and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF http://www.gbif.org). Images including<br />

<strong>plantations</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir remnants were obtained from <strong>the</strong> KDV Architects database (http:<br />

//www.kdvarchitects.com) in Paramaribo.<br />

8

3 Results<br />

3.1 Graphs<br />

Figure 4: Locations <strong>of</strong> collected specimens and species<br />

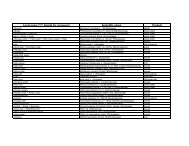

In total, a number <strong>of</strong> 41 botanical vouchers were collected on 27 <strong>plantations</strong>. Among <strong>the</strong>se collected<br />

specimens were plants mentioned by locals as <strong>relics</strong> that were not on <strong>the</strong> list <strong>of</strong> plants<br />

expected as <strong>relics</strong>. Figure 4 shows <strong>the</strong> locations and <strong>the</strong> species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collected specimens. A<br />

complete list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collected species with number, scientific name, vernacular name(s), historical<br />

and current uses is given in Appendix A.<br />

In total, individuals from 18 species that could be regarded as botanical <strong>relics</strong> were collected.<br />

Table 1 summarizes information on relic type, species, reproduction status, cultivation<br />

status and origin. Some specimens <strong>of</strong> ‘original individuals’ 1 were collected, but most specimens<br />

were ‘<strong>of</strong>fspring individuals’ 2 . Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large individuals <strong>of</strong> Tamarindus indica and Erythrina<br />

fusca that were observed might very well date to before <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery. Species can be<br />

potentially attributed and linked to more than a single group. An example is Mangifera indica,<br />

which can be a relic <strong>of</strong> plantation owners, slaves or wage laborers. Pandanus dubius, Musa<br />

balbisiana and <strong>the</strong> black Oryza sativa cultivar are attributed to wage laborers solely, whilst plantation<br />

owner garden <strong>relics</strong> could potentially also be attributed to o<strong>the</strong>r groups. Typical botanical<br />

relic species attributed to African slaves are Phoenix reclinata and Caesalpinia bonduc. Musa<br />

x paradisiaca, Pandanus dubius and <strong>the</strong> black Oryza sativa cultivar were <strong>the</strong> only plants found<br />

1 Original individual: an individual originally planted and managed by people from <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong><br />

2 Offspring individual: an individual that is <strong>of</strong>fspring <strong>of</strong> an original individual<br />

9

solely in cultivation. Plants originating from Asia, Africa and <strong>the</strong> Americas were found, but no<br />

crops from Europe were found to be present at <strong>the</strong> study sites.<br />

Relic type Species<br />

Amerindian<br />

Cash crop<br />

Plantation<br />

structure<br />

Plantation owner<br />

garden<br />

Slave Garden<br />

Wage labourer<br />

Reproduction<br />

status<br />

Cultivation<br />

status<br />

Origin a<br />

Capsicum annuum var.<br />

glabriusculum<br />

<strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Suriname<br />

Bixa orellana <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Suriname<br />

Furcraea foetida <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Suriname<br />

Amaranthus australis <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild N. America<br />

Theobroma cacao <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Amazon<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fea liberica orig. ind. cult. Africa<br />

Bixa orellana <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Amazon<br />

Erythrina fusca <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Suriname<br />

Triphasia trifolia <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Asia<br />

Tamarindus indica orig. ind. cult. Africa<br />

Cereus hexagonus <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Suriname<br />

Trichan<strong>the</strong>ra gigantea <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Suriname<br />

Triphasia trifolia <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Asia<br />

Mangifera indica <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Asia<br />

Tamarindus indica orig. ind. cult. Africa<br />

Phoenix reclinata <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult.? Africa<br />

Musa x paradisiaca <strong>of</strong>fspr. cult., wild? Asia,Africa<br />

Caesalpinia bonduc <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild unknown<br />

Amaranthus australis <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild N. America<br />

Furcraea foetida <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Suriname<br />

Tamarindus indica orig. ind. cult. Africa<br />

Mangifera indica <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. cult., wild? Asia<br />

Oryza sativa <strong>of</strong>fspr. cult. Asia<br />

Musa balbisiana <strong>of</strong>fspr. wild Asia, Africa<br />

Mangifera indica <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Asia<br />

Theobroma cacao <strong>of</strong>fspr., orig. ind. wild, cult. Amazonia<br />

Pandanus dubius orig. ind. cult. Asia<br />

Musa x paradisiaca <strong>of</strong>fspr. cult. Asia,Africa<br />

Source: Abbreviations:<br />

a Rehm and Espig (1991), F.W. Ostendorf (1962) orig. ind.= original individual <strong>of</strong>fspr. = <strong>of</strong>fspring<br />

cult.= cultivated<br />

Table 1: Botanical <strong>relics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname<br />

10

(a) Relics <strong>of</strong> a historical<br />

tamarind lane on plantation<br />

Alliance, Commewijne<br />

3.2 Detailed examples<br />

3.2.1 Amerindian <strong>relics</strong><br />

(b) Cactus <strong>relics</strong> in a hedge in<br />

a swamp forest on plantation<br />

Barbados, Commewijne<br />

Figure 5: Images <strong>of</strong> <strong>relics</strong><br />

(c) Thick mango individuals and<br />

roots on plantation Berg en Dal,<br />

Brokopondo<br />

A collection <strong>of</strong> a bush pepper native to Suriname (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) was<br />

made at <strong>the</strong> abandoned plantation Bent’s Hoop. The vernacular name ‘pepper <strong>of</strong> God’ was<br />

explained by a Javanese elderly woman who heard from her fa<strong>the</strong>r that <strong>the</strong> pepper ‘cannot be<br />

planted by humans, only by God’. On <strong>the</strong> nearby abandoned plantation Kerkshove, Bixa orellana,<br />

used by Amerindians (and African slaves) for its red dye (Ostendorf, 1962), was found<br />

growing wild.<br />

3.2.2 Cash crop <strong>relics</strong><br />

Numerous cacao trees stand in <strong>the</strong> rainforest at <strong>the</strong> former plantation Montpellier, abandoned<br />

since 1840. Locals identified <strong>the</strong>se trees as being from <strong>the</strong> plantation era and indicated <strong>the</strong><br />

variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cacao as one formerly used, but not in recent times (although this could not be<br />

confirmed by <strong>the</strong> literature). A remnant <strong>of</strong> a cacao field was also found at plantation Berlijn.<br />

However, ra<strong>the</strong>r than a remnant <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation era, this was a remnant <strong>of</strong> a field established<br />

after <strong>the</strong> Second World War. After a few bad harvests, ownership changed and currently <strong>the</strong>se<br />

<strong>plantations</strong> are in use for o<strong>the</strong>r agricultural practices such as cattle farming. Remnants <strong>of</strong> cacao<br />

and c<strong>of</strong>fee fields were found on plantation Peperpot, where production stopped a few decades<br />

ago.<br />

11

3.2.3 Plantation structure <strong>relics</strong><br />

Tamarind trees in lanes were a common feature on <strong>plantations</strong>. Drinks from <strong>the</strong>ir fruits were<br />

a welcome refreshment by <strong>the</strong> plantation owners, as an early observer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tree in Suriname<br />

mentioned in Herlein (1718). On <strong>the</strong> former plantation Alliance, a remnant <strong>of</strong> a lane is found<br />

in <strong>the</strong> village (Fig. 5a). Only trees on one side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trail remain as <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs were cut some<br />

decades ago to make place for a hangar.<br />

The tamarind tree collected on <strong>the</strong> abandoned plantation Johanna Charlotte was encountered<br />

in <strong>the</strong> interior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation. There an ‘island’ inside a raised dam (15cm) was present<br />

in <strong>the</strong> swamp. In this ‘island’ shrubs and a few trees, among which <strong>the</strong> tamarind tree, but also<br />

Triphasia trifolia and Cereus hexagonus, were encountered.<br />

The individuals <strong>of</strong> Cereus hexagonus collected at <strong>the</strong> Warappa creek area were found standing<br />

in rows on small dams originating from <strong>the</strong> plantation era on several abandoned <strong>plantations</strong><br />

(Fig. 5b). These hedges stand in coastal swamp vegetation, which has reclaimed large parts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>, but according to <strong>the</strong> Flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas normally this native columnar cactus<br />

is found ‘on sandy ridges near <strong>the</strong> coast and in savanna, on rock outcrops in <strong>the</strong> forest and savanna,<br />

also on riverbanks <strong>of</strong> granite’ (Leuenberger, 1997). Man-made cactus hedges are known<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Dutch Antilles, where <strong>the</strong> hedges were and <strong>of</strong>ten still are placed as a partition (Morton,<br />

1967), and from o<strong>the</strong>r former colonies (Campbell, 1898; Duvall, 2009). No leads on any recent<br />

origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se cactus hedges, nor historical maps depicting cacti hedges were found. Individuals<br />

in <strong>the</strong> open swamp tended to grow less high (1-4m), than individuals in <strong>the</strong> swamp forest<br />

(3-10m). Occasionally, Triphasia trifolia was encountered between Cereus individuals. Triphasia<br />

trifolia is a plant indigenous to Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia, <strong>of</strong>ten used for hedges (Swingle & Reece,<br />

1943). It is still used as a hedge and can be found at <strong>the</strong> presidential palace in Paramaribo. The<br />

co-occurrence <strong>of</strong> those two species fur<strong>the</strong>r supports that <strong>the</strong>y have been used as hedges in <strong>the</strong><br />

past.<br />

On plantation Berlijn, a number <strong>of</strong> Erythrina fusca individuals were found amidst an abandoned<br />

cacao field. The tree was used on <strong>plantations</strong> as a shade tree for juvenile cacao and c<strong>of</strong>fee<br />

plants, also reflected in <strong>the</strong> vernacular name ‘k<strong>of</strong>imama’. This species is <strong>of</strong>ten encountered and<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most widely known botanical <strong>relics</strong>.<br />

3.2.4 Plantation owner garden <strong>relics</strong><br />

Mangifera indica trees were encountered on several <strong>plantations</strong>, that have been urbanized or<br />

abandoned. On plantation Berg en Dal, several thick trees (DBH 460cm, height 12m) with<br />

extensive root systems stood between original slave houses and a plantation owner’s house (Fig.<br />

5c). According to one informant, <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> trees’ root system was visible due to erosion<br />

was an indication <strong>of</strong> old age (Fig. 5c). Mango trees are still common in <strong>the</strong> yards in Paramaribo,<br />

where also large individuals can be encountered.<br />

3.2.5 Slave garden <strong>relics</strong><br />

The Senegal date palm Phoenix reclinata, native to Africa, was probably introduced in Suriname<br />

as food on slave ships. Juveniles and adults were frequently found on <strong>the</strong> coastal <strong>plantations</strong><br />

12

(a) locations observed in <strong>the</strong> field (red dots) and collections from<br />

NHN (yellow dots)<br />

Figure 6: Phoenix reclinata<br />

(b) adult on plantation Reijnsdorp,<br />

Commewijne and fruits<br />

(Fig. 6). Wessels Boer (1965) and Ostendorf (1962) note that this clustered palm was locally<br />

frequent along <strong>the</strong> lower Commewijne river, <strong>the</strong> Suriname river and <strong>the</strong> coastal swamps near<br />

Matapica. Always encountered in a brackish environment, conditions in Suriname appear similar<br />

to <strong>the</strong> palm original habitat in Africa (Von Fintel et al., 2004). The interviews revealed that few<br />

people knew about <strong>the</strong> palm’s African origin and connection to <strong>the</strong> period <strong>of</strong> slavery. Uses<br />

encountered during fieldwork were limited. The fruits (1-2cm) are occasionally eaten, mostly<br />

by children. The fruits can be left in water overnight to enhance <strong>the</strong> ripening. Given <strong>the</strong> palm’s<br />

many uses in Africa (Kinnaird, 1992), much knowledge on this species seems to have been lost.<br />

A local banana variety (Musa x paradisiaca) was collected under <strong>the</strong> vernacular name<br />

‘loweman bakba’. This variety’s fruits have a thick angular peel (Fig. 7a). In Sranan Tongo<br />

(Surinamese language) ‘loweman’ means a runaway slave and ‘bakba’ is a term used for bananas.<br />

This plant was collected in a Javanese community on plantation Reijnsdorp. Interviews<br />

revealed that <strong>the</strong> villagers’ ancestors encountered this plant ‘growing wild in <strong>the</strong> forest’ and that<br />

<strong>the</strong> few remaining former slaves on <strong>the</strong> plantation told <strong>the</strong>m that this was <strong>the</strong> ‘loweman bakba’,<br />

that was grown by slaves and used as food during <strong>the</strong>ir escape from <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>. Also, a<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> ‘loweman bakba’ was made from a yard in Paramaribo. The owner received this<br />

plant from a friend from <strong>the</strong> maroon village Dritabiki (Sipaliwini district in Eastern Suriname).<br />

Due to its drift seed properties, Caesalpinia bonduc occurs naturally along beaches worldwide<br />

(Rehm & Espig, 1991), including <strong>the</strong> coast <strong>of</strong> Suriname. The seeds are widely used as<br />

marbles in a game called ‘agi’ (Ewe) or ‘aware’ (Twi) in Ghana (van Andel et al., 2012). The<br />

‘agi’ game was unknown to most interviewed people, except for one man originally from Dritabiki.<br />

He told that ‘<strong>the</strong> game is still played by some elderly people, but <strong>the</strong> youth does not know<br />

this game. These seeds are known, but <strong>the</strong> game is not played with <strong>the</strong>m anymore’. Maroons<br />

use Ormosia seeds to play <strong>the</strong> ‘agi’ game nowadays (Van Andel, unpublished data).<br />

13

(a) Fruit <strong>of</strong> ‘loweman bakba’<br />

collected on plantation Reijnsdorp,<br />

Commewijne<br />

(b) Ms. Ronowikromo with her<br />

black Oryza cultivar, plantation<br />

Reijnsdorp, Commewijne<br />

Figure 7: Images <strong>of</strong> <strong>relics</strong> II<br />

(c) Banana in abandoned part <strong>of</strong><br />

village on plantation Reijnsdorp,<br />

Commewijne<br />

In Ghana, <strong>the</strong> seeds are also used put as beads on a string around <strong>the</strong> waist <strong>of</strong> a sick child<br />

against skin rashes (van Andel et al., 2012). An elderly Hindustani couple (living around Eastwestverbinding,<br />

km 23.5, Commewijne) knew <strong>the</strong> seeds were medicinally used by making a<br />

bracelet <strong>of</strong> seeds for infants with intestinal problems.<br />

3.2.6 Wage laborer <strong>relics</strong><br />

A black variety <strong>of</strong> Oryza sativa (vernacular name ‘ketan ierang’) was grown for food and ceremonies<br />

(e.g. weddings) at <strong>the</strong> village <strong>of</strong> former plantation Reijnsdorp (Fig. 7b). An elderly<br />

Javanese woman who still plants this rice variety said that it was brought from Java by <strong>the</strong> first<br />

generation migration workers. It used to be commonly planted, but very few people remain that<br />

are involved in planting, harvesting and preparing <strong>the</strong> rice.<br />

Musa balbisiana, a wild banana with seeds native to South Asia and currently considered to<br />

be inedible, was encountered at <strong>the</strong> recently abandoned part <strong>of</strong> Bakkie, <strong>the</strong> village <strong>of</strong> plantation<br />

Reijnsdorp (Fig. 7c). It is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancestors <strong>of</strong> modern cultivated bananas (Musa spp.). Interestingly,<br />

this species does not appear on <strong>the</strong> checklist <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas (Boggan et al., 1997) and is<br />

a new record for Suriname. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inhabitants <strong>of</strong> this village migrated to <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

when Suriname became independent in 1975 (Grasveld, 1986), o<strong>the</strong>rs left for more urbanized<br />

areas, such as Paramaribo. Therefore, it was not possible to interview people that originally lived<br />

at <strong>the</strong> place where this wild banana grew. Given its Asian origin, this species probably came with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Javanese contract laborers to Suriname and can be seen as a relic from <strong>the</strong> plantation period<br />

after <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery.<br />

14

4 Discussion<br />

4.1 Plantations in Suriname and diversity in <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>relics</strong><br />

There existed a large variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in colonial Suriname. The distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>plantations</strong><br />

from coast more inland was characterized by a variation in soil type, rainfall and subsequently<br />

natural vegetation. Also, <strong>the</strong> decline in <strong>the</strong> plantation system was gradual and <strong>plantations</strong>,<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r urbanized, still in production or abandoned, are still changing. These dynamics in<br />

<strong>plantations</strong> have led to diversity in <strong>the</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong>. On abandoned <strong>plantations</strong>, where restoration<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural vegetation occurred due to lack <strong>of</strong> maintenance (a process that started as early<br />

as 1667 (Wolbers, 1861)), <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> <strong>relics</strong> is different from <strong>plantations</strong> that have ceased to<br />

produce crops more recently, or <strong>plantations</strong> that after an initial period <strong>of</strong> urbanization, have seen<br />

a recent de-urbanization (e.g. on plantation Reijnsdorp). Hence, <strong>the</strong> <strong>relics</strong> that may be encountered<br />

are different from one site to <strong>the</strong> next. Plants are dynamic, <strong>the</strong>y grow, reproduce and die.<br />

Whe<strong>the</strong>r a plant is a naturally occurring individual or an actual relic is sometimes difficult to<br />

determine, as is <strong>the</strong> connection <strong>of</strong> a particular relic to <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation on which it<br />

occurs.<br />

Diversity in <strong>the</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong> is evident in various aspects. Relics can be present as<br />

original plant individuals from <strong>the</strong> 17 th century, such as in <strong>the</strong> lanes <strong>of</strong> old tamarind trees at<br />

plantation Alliance. They can also be present as relatively young individuals from <strong>the</strong> recent<br />

past, such as <strong>the</strong> cacao on plantation Berlijn dated to just after World War II. Relics can be<br />

present as <strong>of</strong>fspring (one or more generation <strong>of</strong> descendants from <strong>the</strong> original cultivated plants),<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> cacao fields in <strong>the</strong> forest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation Montpellier. They can be attributed to<br />

different social or ethnic groups (slave owners, slaves or wage laborers, Amerindians, African<br />

or Asian). Relics can be <strong>of</strong> exotic (e.g.Triphasia trifolia) or indigenous origin (e.g.Erythrina<br />

fusca). Those with a known non-indigenous provenance are easier to distinguish as <strong>relics</strong> than<br />

species that naturally occur in Suriname, since <strong>the</strong> human cause <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> latter is<br />

more difficult to prove. Relics <strong>of</strong> Old World origin may have made <strong>the</strong> Atlantic crossing a few<br />

centuries ago (e.g. Tamarindus indica), or more recently (e.g. Musa balbisiana). Relics might<br />

still depend on humans for propagation, such as <strong>the</strong> Oryza sativa cultivar, while o<strong>the</strong>rs have<br />

managed to reproduce by <strong>the</strong>mselves, sometimes even becoming part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural vegetation<br />

(e.g. Phoenix reclinata). Relics can be found as a single individual and as a group <strong>of</strong> individuals<br />

from a single or different species.<br />

4.2 Complications<br />

To attribute a relic to a group and place a relic in time can be difficult. Some species were used by<br />

more than one group <strong>of</strong> people. Also, plant use and knowledge were conveyed from one group to<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r. There are historical examples <strong>of</strong> exchange between Amerindians and African enslaved<br />

peoples (Voeks, 2013; White, 2010). An example from this research is Musa x paradisiaca,<br />

originally planted by slaves, now commonly found in Javanese gardens at plantation Reijnsdorp.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r example is, <strong>the</strong> medicinal use <strong>of</strong> Caesalpinia bonduc, possibly exchanged between (<strong>the</strong><br />

descendants <strong>of</strong>) former slaves and East Indian wage laborers after <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery.<br />

For indigenous species brought to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>, natural dispersal is sometimes a real pos-<br />

15

sibility, especially on <strong>plantations</strong> abandoned long ago. For example, <strong>the</strong> bush pepper collected on<br />

<strong>the</strong> abandoned plantation Bent’s Hoop (Capsicuum annuum var. glabriusculum) could be a relic<br />

<strong>of</strong> Amerindians, <strong>of</strong> a crop managed in <strong>the</strong> gardens <strong>of</strong> slaves, or, coincidentally, may have grown<br />

naturally after abandonment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation. The same holds for Bixa orellana on plantation<br />

Kerkshove. When a tree is naturally common in <strong>the</strong> surrounding vegetation, such as Erythrina<br />

fusca in <strong>the</strong> coastal forest, distinguishing between actual <strong>relics</strong> (individuals planted as a shade<br />

tree for c<strong>of</strong>fee or cacao or <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>of</strong>fspring) and naturally occurring individuals is problematic.<br />

Even introduced species can have similar difficulties. Phoenix reclinata is so well adapted<br />

to its new environment that it managed to spread and become so common that it now appears<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural vegetation. Connection to <strong>the</strong> plantation <strong>of</strong> origin is lost in this case, which<br />

may result in <strong>the</strong> plant spreading outside its original plantation in several generations. In this<br />

case, <strong>the</strong> term relic, comprising something after decline, does not hold well.<br />

Plants that continue to be widely used can be problematic to distinguish as <strong>relics</strong>. Mangifera<br />

indica was present in Suriname before <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> slavery (Dahlberg, 1771; Kappler, 1854)<br />

and is still common today. The age <strong>of</strong> mango trees can be hard to determine by sight, and trees<br />

marked as original individuals from <strong>the</strong> colonial period by locals should be approached with<br />

caution. Several elderly locals that were interviewed mentioned remembering mango trees being<br />

juveniles during <strong>the</strong>ir life, while <strong>the</strong> same trees (DBH 360cm, height 12m) were appointed<br />

as ‘original individuals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colonial period’ by o<strong>the</strong>r (younger) locals.<br />

4.3 Relics in context<br />

Key to placing a relic in context is extracting as much information out <strong>of</strong> available sources as<br />

possible. Useful information for <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> a relic, can be extracted from <strong>the</strong> field. For<br />

example, <strong>the</strong> single tamarind tree on <strong>the</strong> abandoned plantation Johanna Charlotte was without<br />

<strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> a lane. However, <strong>the</strong> fact that Triphasia trifolia and Cereus hexagonus were<br />

found in this ‘island’ as well points to a historical origin. It is not always this straightforward.<br />

On plantation Berg en Dal, <strong>the</strong> thickest mango trees encountered during this study (DBH 460cm,<br />

height 12m) were found between <strong>the</strong> historical buildings. This points towards a relic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plantation era, but on historical images and dioramas <strong>the</strong>se trees could not be distinguished.<br />

For abandoned <strong>plantations</strong>, traits for distinguishing <strong>relics</strong> include increased occurrence<br />

(e.g. as <strong>the</strong> many cacao trees in <strong>the</strong> forest found at plantation Montpellier), unnatural arrangement<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individuals (e.g. as <strong>the</strong> row <strong>of</strong> cacti found on plantation Barbados), occurrence<br />

outside natural habitat (e.g. <strong>the</strong> cacti found in <strong>the</strong> swamp forest near Warappa creek), or presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> non indigenous species.<br />

Local people <strong>of</strong>ten have specific knowledge about <strong>the</strong> plants and plants’ history in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

surroundings, including nearby abandoned areas. Apart from locations <strong>of</strong> plants, interviews<br />

revealed interesting connections in stories on plants, vernacular names and uses. For example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> name ‘loweman bakba’ <strong>of</strong> Musa x paradisiaca shows that <strong>the</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> this cultivar should be<br />

attributed to African slaves ra<strong>the</strong>r than to Asian migrant workers who are presently <strong>the</strong> primary<br />

consumers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> banana. Whilst some knowledge is very common, for example that Erythrina<br />

fusca or ‘k<strong>of</strong>imama’ was used as ‘a tree for mo<strong>the</strong>ring juvenile C<strong>of</strong>fea plants’, o<strong>the</strong>r knowledge<br />

is very specific and only known to a single person.<br />

16

Lastly, in trying to determine age, historical sources such as plantation maps, pictures and<br />

manuscripts containing detailed information on a particular plantation can be useful as well,<br />

although maps that depict individual plants on (part <strong>of</strong>) a plantation are scarce.<br />

Once sufficient knowledge on botanical <strong>relics</strong> is accumulated, <strong>the</strong> human influences in<br />

seemingly natural forest in overgrown <strong>plantations</strong> can be found and understood.<br />

4.4 Tracking plants<br />

In <strong>the</strong> literature some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> encountered species can be tracked and some information on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

connection to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> can be found. For example, Rolander (2008) notes seeing a date<br />

palm in his diary (probably Phoenix reclinata (Van Andel et al., 2012), although he is unaware<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> African origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palm. More than 200 years later, records <strong>of</strong> Phoenix reclinata by<br />

Ostendorf (1962) and Wessels Boer (1965) are made, and <strong>the</strong> African origin <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palm is noted.<br />

Currently, ano<strong>the</strong>r 50 years later, <strong>the</strong> palm has managed to become a part <strong>of</strong> natural vegetation,<br />

as shown in this research. Some o<strong>the</strong>r examples are <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> Trichan<strong>the</strong>ra gigantica as a<br />

windbreaker for juvenile cacao trees and a Pandanaceae species (Pandanus tectorius Parkinson<br />

ex Du Roi) brought from Java in <strong>the</strong> 1910s Ostendorf (1962). However, for o<strong>the</strong>r species and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir connection to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> much is unknown. For example Triphasia trifolia, still used<br />

as a hedge plant in Suriname (e.g. at <strong>the</strong> presidential palace in Paramaribo), was unknown as a<br />

relic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> and questions on its connection to <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname remain.<br />

4.5 Prospects <strong>of</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong><br />

Surinamese citizens are generally interested in plantation history, both in urbanized environments<br />

as well as rural communities. People <strong>of</strong> all ethnic groups in Suriname possess knowledge<br />

on a variety <strong>of</strong> plants and <strong>the</strong>ir uses. Still, botanical heritage is viewed somewhat different, as<br />

people are mostly unaware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> historical connections between certain plants, <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong><br />

and <strong>the</strong> country’s history. The physical botanical heritage is not always seen as valuable, as <strong>the</strong><br />

cutting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient tamarind lane on plantation Alliance demonstrates. Also, <strong>the</strong> government<br />

appears to be doing little to protect this part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s heritage. Private initiatives and<br />

non governmental organizations prove that interest exists to integrate protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> heritage<br />

into <strong>the</strong> country’s policy. Apart from raising historical and environmental awareness among<br />

Surinamers, <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> could provide economic<br />

opportunities for (eco)tourism.<br />

4.6 Follow-up research<br />

In a brief fieldwork period part <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname was revealed<br />

and documented, but surely <strong>the</strong>re is much more to be found. Some potential <strong>relics</strong> mentioned<br />

in <strong>the</strong> literature, such as Sesamum indicum and Elaeis guineensis (Ostendorf, 1962), Indig<strong>of</strong>era<br />

tinctoria, Cleome gynandra (Van Andel et al., 2012) and Oryza glaberrima (Van Andel, 2010)<br />

were not found during this study, but are known to occur and be used elsewhere in Suriname<br />

(Van Andel & Ruysschaert, 2011). O<strong>the</strong>r leads remain to be investigated, for example <strong>the</strong> ‘loweman<br />

bakba’ encountered wild in <strong>the</strong> forest by early contract workers, and <strong>the</strong> apparent cultivation<br />

17

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> banana in some maroon villages. In this sense, this research is meant as an initial step in<br />

revealing <strong>the</strong> full extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation economy and <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>.<br />

More extensive fieldwork, systematically scanning overgrown <strong>plantations</strong> could potentially reveal<br />

much more botanical <strong>relics</strong>.<br />

Genetic research could provide insight in dispersal tracks, such as <strong>the</strong> precise African or<br />

Asian origin <strong>of</strong> Phoenix reclinata and Musa spp., or <strong>the</strong> local source <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cacti hedges in <strong>the</strong><br />

Warappa creek area. Ecological questions, such as <strong>the</strong> extent to which local habitat conditions<br />

affect a relic’s survival, processes that shape relic formation and traits necessary for a species to<br />

become a relic, are worthwhile investigating. Also, different stages and processes <strong>of</strong> regeneration<br />

in humanized landscapes should be studied. In general, this pilot study shows that Suriname<br />

provides an interesting study area for (ethno)botanists, historians, ecologists and archaeologists.<br />

The country’s abandoned <strong>plantations</strong> harbor many hidden treasures waiting to be researched.<br />

5 Conclusion<br />

This study revealed and cataloged a variety <strong>of</strong> botanical <strong>relics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname,<br />

both indigenous and introduced exotics, found ei<strong>the</strong>r as <strong>of</strong>fspring or original individuals, mostly<br />

in <strong>the</strong> wild, but occasionally still cultivated. These <strong>relics</strong> can be placed in different time periods<br />

and can be attributed to Amerindians, slaves, plantation owners or contract workers. There is<br />

some overlap in use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se plants by <strong>the</strong> different groups.<br />

A former production field <strong>of</strong> cacao dating to pre-abolition times, remnants <strong>of</strong> tamarind<br />

lanes, a date palm from Africa becoming part <strong>of</strong> natural vegetation, a banana used by slaves in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir escape from <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong>, remnants <strong>of</strong> cactus hedges in <strong>the</strong> forest, a shade tree for cash<br />

crops still very common, a recently introduced black rice variety in decline, wild hedge plants<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genus Triphasia and a wild banana, a new record for Suriname, were interesting finds.<br />

Some species are good indicator for <strong>the</strong> former presence <strong>of</strong> a plantation, whilst o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

species that occur naturally outside <strong>plantations</strong> are less useful in this sense. Essential to placing<br />

a relic in context is extracting as much information out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surroundings, interviewing locals<br />

about <strong>the</strong>ir knowledge <strong>of</strong> plants in <strong>the</strong>ir community and studying historical manuscripts, maps<br />

and images. Given <strong>the</strong> context, a relic can <strong>of</strong>ten be situated in a certain framework.<br />

In a brief fieldwork period part <strong>the</strong> botanical heritage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>plantations</strong> in Suriname was<br />

revealed, but surely <strong>the</strong>re is much more to be found. This botanical heritage is worthy <strong>of</strong> being<br />

protected. Improving awareness about this heritage could help protect this part <strong>of</strong> Suriname’s<br />

history, be <strong>of</strong> value for education purposes and could provide economic opportunity in<br />

(eco)tourism functions as well.<br />

18

6 Acknowledgements<br />

This research was funded by Stichting het Van Eeden-fonds, Alberta Mennega Stichting, Graeve<br />

Francken Fonds and ALW-Vidi grant <strong>of</strong> dr. T. van Andel. A special thanks to Tinde van Andel<br />

for making this project possible. I would like to thank everybody supporting this project in Suriname<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, I would like to thank Amriet Dubar, David Sanredjo,<br />

Marcio Mantasan, Pieter van der Grift, Tjirundi Nirmal, Silis Dipai, Berto Poeketie, Albie<br />

Poeketie, John Mamastina, Patrick Madari, Armand Kertopawiro, as valuable guides. Also, I<br />

am grateful to Bas Spek <strong>of</strong> Stichting Warappa, Armand van Aalen <strong>of</strong> VABI, Philip Dickland<br />

<strong>of</strong> KDV Architects, Ilonka N. Sjak-Shie <strong>of</strong> Stichting Peperpot, Peter van Huffel <strong>of</strong> Resort de<br />

Plantage and Rosita King-Nijbroek. Talks with Pieter Teunissen, Wim Veer, Iwan Wijngaarde<br />

and Wensley Misiedjan were much valued.<br />

References<br />

Bakhuis, L.A., de Quant, W., & van Rosevelt, J.F.A.C. 1930. Kaart van Suriname. Suriname:<br />

Departement van Kolonien.<br />

Benjamins, H. D., & Snelleman, Joh. F. (ed.). 1914. Encyclopedie van Nederlandsch West-Indie.<br />

Den Haag/Leiden: Martinus Nijh<strong>of</strong>f/E.J. Brill.<br />

Boggan, J., Funk, V., Kell<strong>of</strong>f, C., H<strong>of</strong>f, M., Cremers, G., & Feuillet, C. 1997. Checklist <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas. 2nd edn. Washington, D.C.: Biological Diversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas Program,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Botany, National Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.<br />

Campbell, D.H. 1898. Botanical Aspects <strong>of</strong> Jamaica. The American Naturalist, 32(373), 34–42.<br />

Carney, J. A., & Rosom<strong>of</strong>f, R. N. 2009. In <strong>the</strong> Shadow <strong>of</strong> Slavery Africa’s Botanical Legacy in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Altlantic World. Berkely and Los Angeles, California: University <strong>of</strong> California Press.<br />

Carney, J.A. 2002. Black rice: <strong>the</strong> African origins <strong>of</strong> rice cultivation in <strong>the</strong> Americas. Cambridge,<br />

Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.<br />

Carney, J.A. 2004. ‘With grains in her hair’: rice in colonial Brazil. Slavery & Abolition, 25(1),<br />

1–27.<br />

Carney, J.A. 2005. Rice and memory in <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> enslavement: Atlantic passages to Suriname.<br />

Slavery & Abolition, 26(3), 325–348.<br />

Dahlberg, G. 1771. Catalogus der Vlessen, van de boom, struik, plant en rank, gewassen,<br />

dewelke ik in spiritus vini bewaard heb. unpublished manuscript, Linnean Society <strong>of</strong> London.<br />

De Groot, S.J. 2011. Collecting and Processing Cacti into Herbarium Specimens, Using Ethanol<br />

and O<strong>the</strong>r Methods. Systematic Botany, 36(4), 981–989.<br />

Duvall, C.S. 2009. A maroon legacy? Sketching African contributions to live fencing practices<br />

in early Spanish America. Singapore Journal <strong>of</strong> Tropical Geography, 30(2), 232–247.<br />

19

Emmer, P.C. 1993. Between Slavery and freedom: The period <strong>of</strong> apprenticeship in Suriname<br />

(Dutch Guiana), 1863−1873. Slavery & Abolition, 14(1), 87–113.<br />

Emmer, P.C. 2007. De Nederlandse Slavenhandel 1500-1850. 3rd edn. Amsterdam Antwerpen:<br />

Arbeiderspers.<br />

Fermin, P. 1765. Histoire naturelle de la Hollande equinoxiale. Amsterdam: M. Magerus.<br />

Grasveld, F. 1986. Nog steeds onderweg tussen Bakkie en Hoogezand - Javaanse Surinamers in<br />

Nederland. IF-Produkties, Nederland. Documentaire over Javaanse Surinamers in Nederland<br />

en hun land van herkomst.<br />

Hartsinck, J.J. 1770. Beschryving van Guiana, <strong>of</strong> de Wilde Kust, in Zuid-America. Amsterdam:<br />

Gerrit Tielenburg.<br />

<strong>Heilbron</strong>, U.W. 1982. Kleine boeren in de schaduw van de plantage: de politieke ekonomie van<br />

de na-slavernijperiode in Suriname. Ph.D. <strong>the</strong>sis, University <strong>of</strong> Amsterdam, Amsterdam.<br />

<strong>Heilbron</strong>, U.W. 1993. Colonial transformations and <strong>the</strong> decomposition <strong>of</strong> Dutch plantation<br />

slavery in Surinam. London: Goldsmiths’ College, University <strong>of</strong> London.<br />

Herlein, J.D. 1718. Beschryvinge van de volk-plantinge Zuriname. Leeuwarden: Meindert<br />

Injema.<br />

Hoefte, R. 1996. Free Blacks and Coloureds in Plantation Suriname. Slavery & Abolition, 17(1),<br />

102–129.<br />

Kappler, A. 1854. Zes jaren in Suriname. Schetsen en tafereelen uit het maatschappelijke en<br />

militaire leven in deze kolonie. Utrecht: W.F. Dannenfelser.<br />

Kinnaird, M.F. 1992. Competition for a Forest Palm: Use <strong>of</strong> Phoenix reclinata by Human and<br />

Nonhuman Primates. Conservation Biology, 6(1), 101–107.<br />

Klingelh<strong>of</strong>er, E. 1987. Aspects <strong>of</strong> Early Afro-American Material Culture: Artifacts from <strong>the</strong><br />

Slave Quarters at Garrison Plantation, Maryland. Historical Archaeology, 21(2), 112–119.<br />

Leuenberger, B.E. 1997. Fascicle 18 Cactaceae. In: Gorts-van Rijn, A.R.A., & Jansen-Jacobs,<br />

M.J. (eds), Flora <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Guianas Series A: Phanerogams, vol. 31. Kew Publishing.<br />

Li, Z., Wang, C., Liu, Y., & Li, J. 2012. Microsatellite primers in <strong>the</strong> Chinese dove tree, Davidia<br />

involucrata (Cornaceae), a relic species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tertiary. American Journal <strong>of</strong> Botany, 99(2),<br />

78–80.<br />

Lindeman, J.C., & Moolenaar, S.P. 1953. Preliminary survey <strong>of</strong> vegetation types <strong>of</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Suriname. Pages 395–416 <strong>of</strong>: de Hulster, I.A., & Lanjouw, J. (eds), The Vegetation <strong>of</strong> Suriname,<br />

A Series <strong>of</strong> Papers on <strong>the</strong> Plant Communities <strong>of</strong> Suriname and <strong>the</strong>ir Origin, Distribution<br />

and Relation to Climate and Habitat, vol. I part 2. Van Eedenfonds, Amsterdam, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands.<br />

20

Mann, C.C. 2011. 1493: Uncovering <strong>the</strong> New World Columbus created. London: Granta<br />

Publications.<br />

Mbida, C.M., Van Neer, W., Doutrelepont, H., & Vrydaghs, L. 2000. Evidence for Banana<br />

Cultivation and Animal Husbandry During <strong>the</strong> First Millennium BC in <strong>the</strong> Forest <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Cameroon. Journal <strong>of</strong> Archaeological Science, 27(2), 151–162.<br />

Merian, M.S. 1705. Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensis.<br />

Morgan, P.D. 1997. The cultural implications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Atlantic slave trade: African regional<br />

origins, American destination and new world developments. Slavery & Abolition, 18(1),<br />

122–145.<br />

Morton, J. 1967. Cadushi (Cereus repandus Mill.), a useful cactus <strong>of</strong> Curacao. Economic<br />

Botany, 21(2), 185–191.<br />

Moseberg, I.H. 1801. Nieuwe specialkaart van de colonie Suriname. Suriname: Unknown.<br />

Mousadik, A., & Petit, R. J. 1996. High level <strong>of</strong> genetic differentiation for allelic richness<br />

among populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argan tree Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels] endemic to Morocco. TAG<br />

Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 92(7), 832–839.<br />

Orser, C.E., & Funari, P.P.A. 2001. Archaeology and slave resistance and rebellion. World<br />

Archaeology, 33(1), 61–72.<br />

Ostendorf, F.W. 1962. Nuttige planten en sierplanten in Suriname. 3rd edn. Paramaribo: Landbouwproefstation<br />

in Suriname.<br />

Peel, M.C., Finlayson, B.L., & McMahon, T.A. 2007. Updated world map <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Koppen-Geiger<br />

climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 11, 1633–1644.<br />

Pel, H., Klomp, B., & Pel, J. 2008. Projectplan archeologisch onderzoek van de Boekoe site.<br />

Naarden: Stichting Boekoe.<br />

Price, R. 1991. Subsistence on <strong>the</strong> plantation periphery: crops, cooking, and labour among<br />

eighteenth century Suriname maroons. Slavery & Abolition, 12(1), 107–127.<br />

Pryor, F.L. 1982. The plantation economy as an economic system. Journal <strong>of</strong> Comparative<br />

Economics, 6(3), 288–317.<br />

Rehm, S., & Espig, G. 1991. The cultivated plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tropis and Subtropics. Wageningen,<br />

The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands & Weikersheim, West Germany: Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural<br />

Cooperation (CTA) & Verlag Josef Margraf.<br />

Rolander, D. 2008. The Suriname Journal: composed during an exotic journey. (trans. J. Dobreff,<br />

C. Dahlman, D. Morgan and J. Tipton). Vol. 3 Hansen, J. (ed.), The Linnaeus apostles:<br />

Global science & adventure, Europe, North & South America, book 3, Pehr Lfling, Daniel<br />

Rolander. London: IK Foundation.<br />

21

Schiebinger, L.L. 2004. Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in <strong>the</strong> Atlantic World.<br />

Harvard: Harvard University Press.<br />

Singleton, T.A. 1995. The Archaeology <strong>of</strong> Slavery in North America. Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Anthropology,<br />

24, 119–140.<br />

Stahel, G. 1944. De nuttige planten in Suriname, Bulletin 59. Paramaribo: Departement Landbouwproefstation<br />

in Suriname.<br />

Swingle, W.T., & Reece, P.C. 1943. The botany <strong>of</strong> Citrus and its wild relatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orange<br />

subfamily. Vol. I: The Citrus Industry, H.J. Webber and L.D. Batchelor (Eds.) History, World<br />

Distribution, Botany, and Varieties. California: University <strong>of</strong> California.<br />

Van Andel, T. 2010. African Rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud.): Lost Crop <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Enslaved<br />

Africans Discovered in Suriname. Economic Botany, 64(1), 1–10.<br />

Van Andel, T., & Ruysschaert, S. 2011. Medicinale en rituele planten van Suriname. Amsterdam:<br />

KIT publishers.<br />

Van Andel, T., Maas, P., & Dobreff, J. 2012. Ethnobotanical notes from Daniel Rolander’s<br />

Diarium Surinamicum (1754-1756): Are <strong>the</strong>se plants still used in Suriname today? Taxon,<br />

61(4), 852–863.<br />

van Andel, T., Myren, B., & van Onselen, S. 2012. Ghana’s herbal market. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Ethnopharmacology, 140(2), 368–378.<br />

Van Andel, T., Veldman, S., Maas, P., G., Thijsse, & Eurlings, M. in press. The forgotten<br />

Hermann Herbarium: A 17th century collection <strong>of</strong> useful plants from Suriname. Taxon.<br />

Van Lier, R.A.J. 1977. Samenleving in een Grensgebied. 3rd edn. Amsterdam: S. Emmering.<br />

Versteeg, A.H. 1992. Environment and man in <strong>the</strong> young coastal plain <strong>of</strong> West Suriname. Pages<br />

531–540 <strong>of</strong>: Evolution des littoraux de Guyane et de la zone Caraiebe Meridionale pendant<br />

le Quaternaire. Colloques et Seminaires. Marseille: ORSTOM.<br />

Versteeg, A.H. 1998. The history <strong>of</strong> archaeological research in Suriname. Pages 203–234 <strong>of</strong>:<br />

Th.E. Wong, D.R. de Vletter, L. Krook, J.I.S. Zonneveld & A.J. van Loon (eds.) The history <strong>of</strong><br />

earth sciences in Suriname. Amsterdam: Royal Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Academy <strong>of</strong> Arts and Sciences<br />

KNAW & Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Geoscience TNO.<br />

Voeks, Robert. 2013. Ethnobotany <strong>of</strong> Brazils African Diaspora: The Role <strong>of</strong> Floristic Homogenization.<br />

Pages 395–416 <strong>of</strong>: Voeks, Robert, & Rashford, John (eds), African Ethnobotany in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Americas. Springer New York.<br />

Von Fintel, G.T., Berjak, P., & Pammenter, N.W. 2004. Seed behaviour in Phoenix reclinata<br />

Jacquin, <strong>the</strong> wild date palm. Seed Science Research, 14(02), 197–204.<br />

Wessels Boer, J.G. 1965. The indigenous palms <strong>of</strong> Suriname. Ph.D. <strong>the</strong>sis, Universiteit Utrecht,<br />

Leiden.<br />

22