Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

12<br />

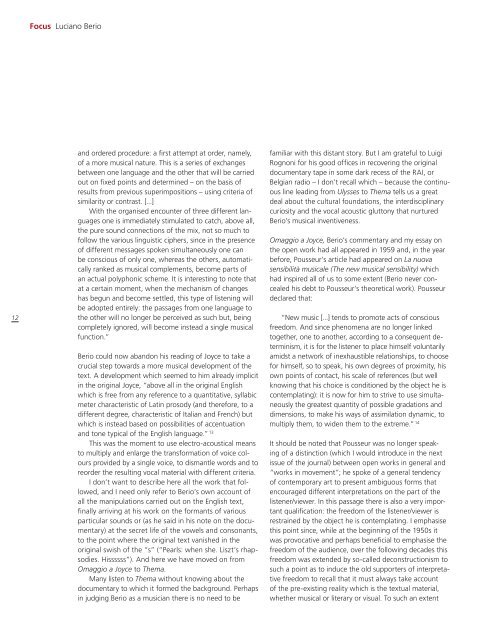

focus Luciano Berio<br />

and ordered procedure: a first attempt at order, namely,<br />

of a more musical nature. This is a series of exchanges<br />

between one language and the other that will be carried<br />

out on fixed points and determined – on the basis of<br />

results from previous superimpositions – using criteria of<br />

similarity or contrast. [...]<br />

With the organised encounter of three different languages<br />

one is immediately stimulated to catch, above all,<br />

the pure sound connections of the mix, not so much to<br />

follow the various linguistic ciphers, since in the presence<br />

of different messages spoken simultaneously one can<br />

be conscious of only one, whereas the others, automatically<br />

ranked as musical complements, become parts of<br />

an actual polyphonic scheme. It is interesting to note that<br />

at a certain moment, when the mechanism of changes<br />

has begun and become settled, this type of listening will<br />

be adopted entirely: the passages from one language to<br />

the other will no longer be perceived as such but, being<br />

completely ignored, will become instead a single musical<br />

function.”<br />

Berio could now abandon his reading of Joyce to take a<br />

crucial step towards a more musical development of the<br />

text. A development which seemed to him already implicit<br />

in the original Joyce, “above all in the original English<br />

which is free from any reference to a quantitative, syllabic<br />

meter characteristic of Latin prosody (and therefore, to a<br />

different degree, characteristic of Italian and French) but<br />

which is instead based on possibilities of accentuation<br />

and tone typical of the English language.” 13<br />

This was the moment to use electro-acoustical means<br />

to multiply and enlarge the transformation of voice colours<br />

provided by a single voice, to dismantle words and to<br />

reorder the resulting vocal material with different criteria.<br />

I don’t want to describe here all the work that followed,<br />

and I need only refer to Berio’s own account of<br />

all the manipulations carried out on the English text,<br />

finally arriving at his work on the formants of various<br />

particular sounds or (as he said in his note on the documentary)<br />

at the secret life of the vowels and consonants,<br />

to the point where the original text vanished in the<br />

original swish of the “s” (“Pearls: when she. Liszt’s rhapsodies.<br />

Hissssss”). And here we have moved on from<br />

Omaggio a Joyce to Thema.<br />

Many listen to Thema without knowing about the<br />

documentary to which it formed the background. Perhaps<br />

in judging Berio as a musician there is no need to be<br />

familiar with this distant story. But I am grateful to Luigi<br />

Rognoni for his good offices in recovering the original<br />

documentary tape in some dark recess of the RAI, or<br />

Belgian radio – I don’t recall which – because the continuous<br />

line leading from Ulysses to Thema tells us a great<br />

deal about the cultural foundations, the interdisciplinary<br />

curiosity and the vocal acoustic gluttony that nurtured<br />

Berio’s musical inventiveness.<br />

Omaggio a Joyce, Berio’s commentary and my essay on<br />

the open work had all appeared in 1959 and, in the year<br />

before, Pousseur’s article had appeared on La nuova<br />

sensibilità musicale (The new musical sensibility) which<br />

had inspired all of us to some extent (Berio never concealed<br />

his debt to Pousseur’s theoretical work). Pousseur<br />

declared that:<br />

“New music [...] tends to promote acts of conscious<br />

freedom. And since phenomena are no longer linked<br />

together, one to another, according to a consequent determinism,<br />

it is for the listener to place himself voluntarily<br />

amidst a network of inexhaustible relationships, to choose<br />

for himself, so to speak, his own degrees of proximity, his<br />

own points of contact, his scale of references (but well<br />

knowing that his choice is conditioned by the object he is<br />

contemplating): it is now for him to strive to use simultaneously<br />

the greatest quantity of possible gradations and<br />

dimensions, to make his ways of assimilation dynamic, to<br />

multiply them, to widen them to the extreme.” 14<br />

It should be noted that Pousseur was no longer speaking<br />

of a distinction (which I would introduce in the next<br />

issue of the journal) between open works in general and<br />

“works in movement”; he spoke of a general tendency<br />

of contemporary art to present ambiguous forms that<br />

encouraged different interpretations on the part of the<br />

listener/viewer. In this passage there is also a very important<br />

qualification: the freedom of the listener/viewer is<br />

restrained by the object he is contemplating. I emphasise<br />

this point since, while at the beginning of the 1950s it<br />

was provocative and perhaps beneficial to emphasise the<br />

freedom of the audience, over the following decades this<br />

freedom was extended by so-called deconstructionism to<br />

such a point as to induce the old supporters of interpretative<br />

freedom to recall that it must always take account<br />

of the pre-existing reality which is the textual material,<br />

whether musical or literary or visual. To such an extent