Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Download a PDF file - Universal Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

14<br />

focus Luciano Berio<br />

It was already clear that Sequenza I was “in movement”<br />

in a different way to the other two works, and allowed a<br />

fairly limited freedom of initiative to the performer, which<br />

did not compromise the syntactic structure of the piece.<br />

But the interest at the time was to put forward “extreme”<br />

examples to emphasise these very aspects of openness.<br />

Now, however, a philologically well-founded dispute<br />

has broken out over the supposed freedom that<br />

Sequenza I allows its performer. of<br />

the essays in the recently-published<br />

Berio’s Sequenzas, I will refer only<br />

to those by Cynthia Folio and<br />

Alexander R. Brinkmann (Rhythm<br />

and Timing in the Two Versions of<br />

Berio’s “Sequenza I” for Flute Solo:<br />

Psychological and Musical Differences<br />

in Performance), by Edward<br />

venn (Proliferations and Limitations:<br />

Berio’s Reworking of the “Sequenzas”) and by Irna Priore<br />

(Vèstiges of Twelve-Tones Practice as Compositional Process<br />

in Berio’s “Sequenza I” for Solo Flute). 18<br />

The first essay suggests that I had misunderstood Berio’s<br />

work which, in fact, does not constitute an example<br />

of work in movement. In venn’s essay it is said that in<br />

publishing my article Berio was complicit in spreading this<br />

misunderstanding (and Venn does not know that Berio<br />

was complicit not only in publishing the article but in<br />

suggesting and supervising the expressions I had used).<br />

It therefore seems that Berio had changed his idea at a<br />

certain point, as is confirmed by what he had said in 1981<br />

to Rossana Dalmonte in Intervista sulla musica:<br />

“The piece is very difficult; for this I had adopted<br />

a very particular notation but with certain margins of<br />

flexibility so that the performer could have the freedom<br />

– psychological rather than musical – to adapt the piece<br />

here and there to his or her technical stature. Instead, this<br />

very notation has allowed many performers – whose most<br />

shining virtue was certainly not professional integrity – to<br />

make adaptations more or less unauthorised. I intend<br />

to rewrite Sequenza I in rhythmic notation: it will be less<br />

‘open’ and more authoritarian, perhaps, but certainly more<br />

reliable. And I hope Umberto Eco will forgive me ...” 19<br />

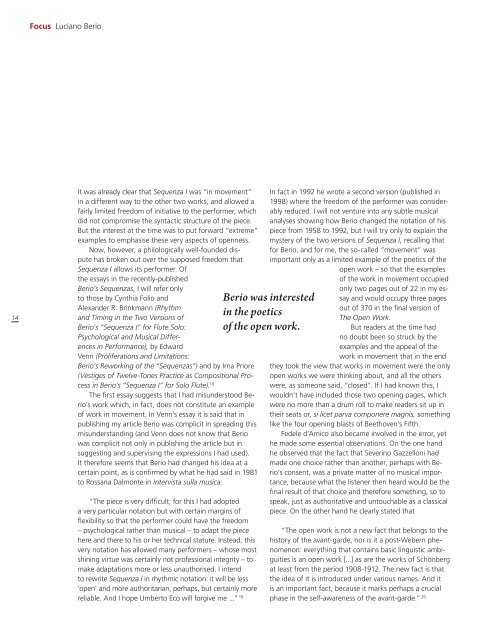

Berio was interested<br />

in the poetics<br />

of the open work.<br />

In fact in 1992 he wrote a second version (published in<br />

1998) where the freedom of the performer was considerably<br />

reduced. I will not venture into any subtle musical<br />

analyses showing how Berio changed the notation of his<br />

piece from 1958 to 1992, but I will try only to explain the<br />

mystery of the two versions of Sequenza I, recalling that<br />

for Berio, and for me, the so-called “movement” was<br />

important only as a limited example of the poetics of the<br />

open work – so that the examples<br />

of the work in movement occupied<br />

only two pages out of 22 in my es-<br />

say and would occupy three pages<br />

out of 370 in the final version of<br />

The Open Work.<br />

But readers at the time had<br />

no doubt been so struck by the<br />

examples and the appeal of the<br />

work in movement that in the end<br />

they took the view that works in movement were the only<br />

open works we were thinking about, and all the others<br />

were, as someone said, “closed”. If I had known this, I<br />

wouldn’t have included those two opening pages, which<br />

were no more than a drum roll to make readers sit up in<br />

their seats or, si licet parva componere magnis, something<br />

like the four opening blasts of Beethoven’s Fifth.<br />

Fedele d’Amico also became involved in the error, yet<br />

he made some essential observations. on the one hand<br />

he observed that the fact that Severino Gazzelloni had<br />

made one choice rather than another, perhaps with Berio’s<br />

consent, was a private matter of no musical importance,<br />

because what the listener then heard would be the<br />

final result of that choice and therefore something, so to<br />

speak, just as authoritative and untouchable as a classical<br />

piece. on the other hand he clearly stated that<br />

“The open work is not a new fact that belongs to the<br />

history of the avant-garde, nor is it a post-Webern phenomenon:<br />

everything that contains basic linguistic ambiguities<br />

is an open work [...] as are the works of Schönberg<br />

at least from the period 1908-1912. The new fact is that<br />

the idea of it is introduced under various names. And it<br />

is an important fact, because it marks perhaps a crucial<br />

phase in the self-awareness of the avant-garde.” 20