rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

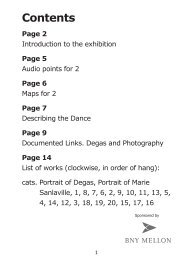

4<br />

‘I place the model in such a way<br />

that it stands out against the<br />

background and so that the light<br />

falls on this pr<strong>of</strong>ile. I execute it,<br />

and move both my turntable<br />

and that <strong>of</strong> the model, so that I<br />

can see another pr<strong>of</strong>ile.Then I<br />

turn them again, and gradually<br />

work my way around the figure.’<br />

RODIN<br />

Republic created a demand for sculptural monuments that <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

some sense <strong>of</strong> consolation to the nation. Rodin’s figure was originally<br />

called The Vanquished, and he began work with a Belgian soldier,<br />

Augustus Neyt, as his model. He had developed a system <strong>of</strong> modelling<br />

that depended on recording a clear outline <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> a figure<br />

seen from as many angles as was felt necessary.<br />

Rodin interrupted work on his figure by making a trip to Italy in<br />

early 1876.There he saw not only antique sculpture but the work <strong>of</strong><br />

Donatello (1386–1466), Michelangelo (1475–1564) and other Italian<br />

sculptors. Recalling his experience <strong>of</strong> Michelangelo’s Medici Tombs he<br />

said ‘we notice that his sculpture expresses the painful withdrawal <strong>of</strong><br />

the being into himself, restless energy.’This was in contrast to the<br />

‘quietude, grace, balance, reason’ <strong>of</strong> antique art.<br />

Originally conceiving the sculpture with a spear in the raised<br />

arm to suggest a vanquished soldier sensing the meaning <strong>of</strong> defeat,<br />

Rodin removed this accessory shortly before showing the work in<br />

Brussels. Deprived <strong>of</strong> this clue to its meaning, a critic asked:‘can this<br />

be a statue <strong>of</strong> a sleep walker?’ For its showing in Paris Rodin<br />

changed the title, making reference to the classical third stage<br />

<strong>of</strong> man’s development.<br />

Cat. 11 The pose, with arm raised to head, owes something to<br />

Michelangelo’s Dying Slave in the Louvre, but with the weight firmly<br />

on his left foot the figure has a classical balance and poise.What is<br />

remarkable is the supple and smoothly modelled transitions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

various parts <strong>of</strong> the body, like the feeling <strong>of</strong> the rib cage giving way to<br />

the stomach and then to the gentle curve <strong>of</strong> the belly. Neyt wrote that<br />

‘Rodin did not want any exaggerated muscle, he wanted naturalness’ –<br />

a naturalness that is brought to life by the way in which the delicately<br />

moulded surfaces reflect the light in a discontinuous fashion.<br />

How does Rodin create a sense <strong>of</strong> imminent movement?<br />

Given that the best points <strong>of</strong> view are from the front and to the spectator’s<br />

right, why might Rodin have removed the spear?<br />

The Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), who was briefly<br />

Rodin’s secretary, wrote most sensitively about the emotional qualities<br />

<strong>of</strong> his sculpture.‘That which was expressed in the face, that pain <strong>of</strong> a<br />

heavy awakening and at the same time the longing for that awakening,<br />

was written on the smallest part <strong>of</strong> this body. Every part was a mouth<br />

that spoke a language <strong>of</strong> its own.’<br />

Critics at the Salon were less acute, referring to ‘a curious atelier<br />

study with a very pretentious name.’The most damning accusation<br />

claimed that the figure was a cast from life. Rodin protested vigorously,<br />

ordering photographs <strong>of</strong> Neyt in the pose so comparisons could be<br />

made, along with written statements <strong>of</strong> the time involved, and even an<br />

actual cast. In one sense the furore attracted attention to the unknown<br />

thirty-seven-year-old and brought him supporters as well as detractors.<br />

THE GATES OF HELL<br />

Rodin’s problems over The Age <strong>of</strong> Bronze had one marvellous<br />

consequence. Edmund Turquet, a member <strong>of</strong> the committee<br />

investigating the charge <strong>of</strong> casting from life, had been made Undersecretary<br />

for Fine <strong>Arts</strong> in 1879. Early in the following year he discussed<br />

with Rodin the possible commission <strong>of</strong> a set <strong>of</strong> monumental doors for<br />

the proposed Museum <strong>of</strong> Decorative Art. Rodin suggested a theme<br />

based on the Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s (1265–1321) Inferno that<br />

would be expressed through many small figures in low relief. Rodin had<br />

been encouraged to read poetry at the Petit Ecole and Dante had<br />

already exerted a pr<strong>of</strong>ound influence on French Romantic artists. His<br />

proposal was accepted and in July <strong>of</strong> 1880 he moved into a<br />

government studio at the Dépôt des Marbres on the rue de<br />

l’Université and began work on a project that completely changed his<br />

way <strong>of</strong> making sculpture and whose influence would last for the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

his life.<br />

The Inferno is the first part <strong>of</strong> Dante’s Divine Comedy, a description<br />

<strong>of</strong> hell seen as a series <strong>of</strong> descending circles in which different<br />

categories <strong>of</strong> crimes and their eternal punishments are illustrated<br />

through his encounters with individual sinners. It is uncertain whether<br />

Rodin intended to reflect the stories and structure <strong>of</strong> the Inferno or<br />

rather to conjure up the words <strong>of</strong> Dante’s guide, the Roman poet Virgil<br />

(70–19 BC):<br />

‘Through me you go into the city <strong>of</strong> weeping;<br />

Through me you go into eternal pain;<br />

Through me you go among the lost people.’<br />

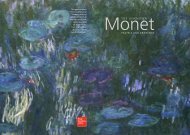

In the end Rodin used only two identifiable groupings,<br />

the adulterous lovers Paolo and Francesca (The Kiss), and<br />

Count Ugolino, betrayer <strong>of</strong> Pisa, starved into committing<br />

cannibalism on his sons and grandsons. Ugolino can be<br />

seen in fig. 1, one <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> imaginative drawings in<br />

which Rodin explored ‘the spirit <strong>of</strong> this remarkable poet’,<br />

whose expression he felt ‘is always primitive and<br />

sculptural.’ Using pencil, followed by Indian ink to<br />

strengthen the outlines and create a sense <strong>of</strong> mass,<br />

Rodin adds gouache to emphasise the sculptural effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> raking light. Dealing with themes <strong>of</strong> anguish, struggle<br />

and confinement, these drawings frequently have a<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> claustrophobic intensity as Rodin explores<br />

a vocabulary <strong>of</strong> gesture and form, that while not directly<br />

related to individual sculptures, helped to influence the<br />

overall conception. But, as he told a journalist in 1900:<br />

‘I realised that my drawings were too far removed<br />

from reality. I started all over again and worked from<br />

life with models.’<br />

Rodin was financially free to employ as many models<br />

as he liked, and they were encouraged to roam the<br />

studio, taking up poses while Rodin modelled in clay<br />

those that caught his imagination. He frequently stated<br />

that ‘Nature’ was the source <strong>of</strong> his inspiration, but at the<br />

Fig.1<br />

Ugolino, also called Ugolino First Day,<br />

c.1880<br />

Graphite, pen, brown wash and<br />

gouache on cream-coloured paper<br />

19.3 x 12 cm<br />

Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon, D. 9393<br />

Photo © Musée Rodin/Jean de Calan<br />

5