rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

While Rodin said that there was ‘no scheme <strong>of</strong> illustration or<br />

intended moral purpose’, his work expresses a view <strong>of</strong> the spiritual<br />

state <strong>of</strong> his time and conforms with his belief that works <strong>of</strong> art ‘say<br />

everything that one can say about man and the world. Besides, they<br />

make us understand that there is something else that one cannot<br />

know.’ It was Rilke who said that Rodin’s art was ‘to help a time whose<br />

misfortune was that all its conflicts lay in the invisible.’<br />

After four years <strong>of</strong> intense work on The Gates it became clear that<br />

the French Government was uncertain whether to build the museum<br />

that The Gates would have adorned. A completion date receded into<br />

the distance and Rodin, who was averse to finishing anything, may have<br />

been relieved. More work was done between 1887 and 1889 for a<br />

possible showing at the Exposition in honour <strong>of</strong> the centenary <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Revolution, and judging from comments by visitors to the studio and<br />

contemporary photographs, the major artistic decisions had been<br />

taken by that date. In fact the first public showing <strong>of</strong> a plaster cast <strong>of</strong><br />

The Gates did not take place until Rodin’s 1900 exhibition and then<br />

without many <strong>of</strong> the free-standing and high-relief figures.The first<br />

bronze cast was made in 1926, by the director <strong>of</strong> the Rodin Museum.<br />

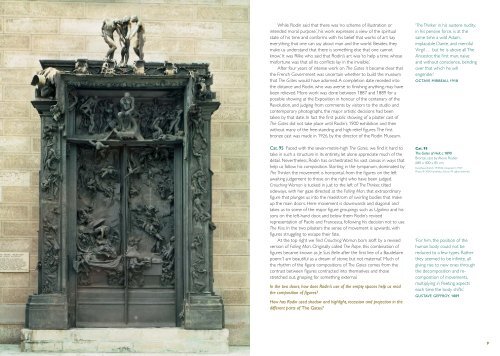

Cat. 95 Faced with the seven-metre-high The Gates, we find it hard to<br />

take in such a structure in its entirety, let alone appreciate much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

detail. Nevertheless, Rodin has orchestrated his vast canvas in ways that<br />

help us follow his composition. Starting in the tympanum, dominated by<br />

The Thinker, the movement is horizontal, from the figures on the left<br />

awaiting judgement to those on the right who have been judged.<br />

Crouching Woman is tucked in just to the left <strong>of</strong> The Thinker, tilted<br />

sideways, with her gaze directed at the Falling Man, that extraordinary<br />

figure that plunges us into the maelstrom <strong>of</strong> swirling bodies that make<br />

up the main doors. Here movement is downwards and diagonal and<br />

takes us to some <strong>of</strong> the major figure groupings such as Ugolino and his<br />

sons on the left-hand door, and below them Rodin’s revised<br />

representation <strong>of</strong> Paolo and Francesca, following his decision not to use<br />

The Kiss. In the two pilasters the sense <strong>of</strong> movement is upwards, with<br />

figures struggling to escape their fate.<br />

At the top right we find Crouching Woman born al<strong>of</strong>t by a revised<br />

version <strong>of</strong> Falling Man. Originally called The Rape, this combination <strong>of</strong><br />

figures became known as Je Suis Belle after the first line <strong>of</strong> a Baudelaire<br />

poem:‘I am beautiful as a dream <strong>of</strong> stone; but not maternal.’ Much <strong>of</strong><br />

the rhythm <strong>of</strong> the figure compositions <strong>of</strong> The Gates comes from the<br />

contrast between figures contracted into themselves and those<br />

stretched out, grasping for something external.<br />

In the two doors, how does Rodin’s use <strong>of</strong> the empty spaces help us read<br />

the composition <strong>of</strong> figures?<br />

How has Rodin used shadow and highlight, recession and projection in the<br />

different parts <strong>of</strong> The Gates?<br />

‘The Thinker in his austere nudity,<br />

in his pensive force, is at the<br />

same time a wild Adam,<br />

implacable Dante, and merciful<br />

Virgil … but he is above all The<br />

Ancestor, the first man, naive<br />

and without conscience, bending<br />

over that which he will<br />

engender.’<br />

OCTAVE MIRBEAU, 1918<br />

Cat. 95<br />

The Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell, c.1890<br />

Bronze, cast by Alexis Rudier<br />

680 x 400 x 85 cm<br />

Kunsthaus Zürich, 1949/22. Acquired in 1947<br />

Photo © 2006 Kunsthaus Zürich. All rights reserved.<br />

‘For him, the position <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human body could not be<br />

reduced to a few types. Rather<br />

they seemed to be infinite, all<br />

giving rise to new ones through<br />

the decomposition and recomposition<br />

<strong>of</strong> movements,<br />

multiplying in fleeting aspects<br />

each time the body shifts.’<br />

GUSTAVE GEFFROY, 1889<br />

9