rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

rodin - Royal Academy of Arts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This guide is given out free to teachers and students with an exhibition ticket and student<br />

or teacher ID at the Education Desk.<br />

It is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost <strong>of</strong> £3.95 (while stocks last).<br />

RODIN

RODIN<br />

This exhibition has been organised by the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Arts</strong>, London, and the Kunsthaus Zürich in collaboration with<br />

the Musée Rodin, Paris.<br />

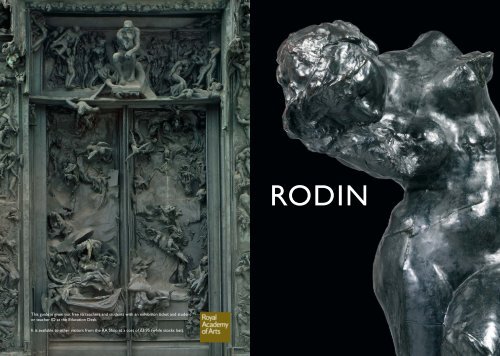

FRONT COVER<br />

Detail <strong>of</strong> Cat. 205<br />

BACK COVER<br />

Detail <strong>of</strong> Cat. 195<br />

Designed by Isambard Thomas, London<br />

Printed by Burlington<br />

‘I saw clay for the first time: I thought I was ascending to heaven.<br />

I made separate pieces, arms, heads or feet;<br />

then I made an entire figure.<br />

I grasped the whole thing in a flash …<br />

I was enraptured.’ RODIN, 1913<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

In 1900, the sixty-year-old Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) built a<br />

temporary pavilion on Place de l’Alma in Paris to house a retrospective<br />

display <strong>of</strong> his work, coinciding with the Universal Exposition <strong>of</strong> that<br />

year. His exhibition was to <strong>of</strong>fer a vision <strong>of</strong> concentrated intensity, in<br />

marked contrast to the overwhelming variety <strong>of</strong> painters, sculptors,<br />

subjects and styles that visitors would have encountered elsewhere.<br />

Here was an artist who had overthrown most <strong>of</strong> the academic rules <strong>of</strong><br />

mid-nineteenth-century sculpture. He rejected idealisation in favour <strong>of</strong><br />

an honest response to nature. Seeing conventions <strong>of</strong> sculptural stability<br />

as static and lifeless, he found ways <strong>of</strong> suggesting movement, not only in<br />

the forms <strong>of</strong> his figures, but by abandoning smooth finish in favour <strong>of</strong> a<br />

pulsating surface alive to the play <strong>of</strong> light.The sanitised sexuality in<br />

conventional representations <strong>of</strong> Venus and nymphs would be replaced<br />

by an array <strong>of</strong> figures that obsessively explored genuine erotic themes.<br />

Questioning the integrity <strong>of</strong> the human form, he succeeded in showing<br />

that partial figures could make a complete sculptural statement.<br />

Already the most notorious sculptor in France, Rodin gained an<br />

international clientele, not least in England, where collectors were eager<br />

to purchase bronze or marble versions <strong>of</strong> his most famous sculptures,<br />

and upper-class ladies sought to commission portrait busts. Lionised by<br />

English society, Rodin resumed visits to the country, which despite<br />

critical acclaim for his work, he had regarded with some suspicion,<br />

following his rejection at the 1886 <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> exhibition and an<br />

abortive trip to effect a reconciliation with his errant mistress, the<br />

sculptor Camille Claudel (1864–1943), in the same year.While Rodin<br />

now enjoyed country-house entertainment, it became increasingly<br />

fashionable to visit his Parisian studios to understand the master at<br />

work, to see the vast array <strong>of</strong> figures and forms he drew upon and to<br />

appreciate the number <strong>of</strong> studies that preceded a finished sculpture.<br />

LEARNING TO SCULPT<br />

Rodin’s family had come to Paris in the 1830s, attracted by the<br />

expanding metropolis, and his father Jean-Baptiste had a minor clerical<br />

post in the Prefecture <strong>of</strong> Police. Realising that his son’s poor academic<br />

record would not equip him for the life <strong>of</strong> a clerk, his father agreed to<br />

allow Auguste, at the age <strong>of</strong> fourteen, to develop his passionate interest<br />

in drawing at the Petite Ecole, a free school that trained its pupils to<br />

enter the decorative arts.<br />

‘Little by little, the dominant<br />

impression, which was initially<br />

that <strong>of</strong> shyness, became that <strong>of</strong><br />

a tranquil, unusual authority.<br />

Nothing about the man was<br />

grandiloquent, nor was anything<br />

awkward … An immense latent<br />

energy arose from his sober<br />

movements, made manifest by<br />

all the measure that governed<br />

them.’<br />

CAMILLE MAUCLAIR, 1904<br />

1

2<br />

‘What is modelling? The very<br />

principle <strong>of</strong> creation. It is the<br />

juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> the innumerable<br />

reliefs and depressions that<br />

constitute every fragment <strong>of</strong><br />

matter, inert or animated.<br />

Modelling creates the essential<br />

texture, supple, living, embracing<br />

every plane. It fills, co-ordinates<br />

and harmonises them.’<br />

RODIN TO HIS BIOGRAPHER<br />

JUDITH CLADEL<br />

Cat. 11<br />

The Age <strong>of</strong> Bronze, 1877<br />

Bronze<br />

181 x 60 x 60 cm<br />

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, A33-1914.<br />

Rodin Donation, 1914<br />

Photo © V&A Images/V&A Museum<br />

The principal discipline was drawing but, unusually, the teaching was<br />

flexible and imaginative. As well as drawing the traditional plaster casts<br />

and friezes, students were encouraged to develop their spontaneity in<br />

the life room by drawing models who were allowed to move and take<br />

up shorter poses. Much emphasis was placed on drawing from<br />

memory. In the second year his experience with clay modelling enabled<br />

Rodin to find his vocation.<br />

The best students would go on to the Ecole des Beaux <strong>Arts</strong> but<br />

Rodin was to fail the entrance exam in three successive years, each<br />

time failing the sculpture test. Success would have given him access to<br />

the tuition <strong>of</strong> sculptors whose contacts would have guaranteed him a<br />

career in the French Salon. A friend later remarked that he was lucky<br />

to have failed.<br />

THE UNACKNOWLEDGED ASSISTANT<br />

We know very little about Rodin’s attempts to support himself in these<br />

early years, working for goldsmiths, restorers or stone masons, while<br />

struggling to do his own work.The influence <strong>of</strong> Roman portrait busts<br />

can be felt in those he made <strong>of</strong> his father and the priest Pierre-Julien<br />

Eymard, who had helped Rodin through a religious crisis following the<br />

death <strong>of</strong> his elder sister Maria in 1862. In 1864 Rodin met Rose Beuret<br />

and a son was born in 1866. Rose remained his partner for the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

his life.<br />

Rodin’s first submission to the French Salon, The Mask <strong>of</strong> the Man<br />

with the Broken Nose, was rejected in 1865, its non-idealised portrayal<br />

<strong>of</strong> a local odd job man, Bibi, too down-to-earth for the Salon jury. By<br />

that time Rodin had joined the studio <strong>of</strong> Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse<br />

(1824–1877), a talented sculptor who adopted the elegant eighteenthcentury<br />

Rococo style that was fashionable in Second-Empire France.<br />

Working on figurines, busts and ornaments for commercial sale, as well<br />

as on public monuments, Rodin’s technical skills developed apace.The<br />

experience <strong>of</strong> a large studio enabled him to understand the business<br />

and organisational skills needed to be a successful sculptor.<br />

Following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war <strong>of</strong> 1870,<br />

Carrier-Belleuse moved to Brussels. Rodin followed him in 1871, and<br />

their collaboration continued until Rodin’s desire to market small<br />

bronzes under his own name caused a break. He began a partnership<br />

with Joseph van Rasbourgh, working on large statues for the<br />

decoration <strong>of</strong> buildings. Rose had joined him, and they stayed on in<br />

Brussels in what was to be the happiest time <strong>of</strong> their relationship.<br />

THE AGE OF BRONZE<br />

In 1875, a marble version <strong>of</strong> The Man with the Broken Nose, carved by a<br />

specialist in Paris, was accepted by the Salon. Believing that ‘an artist<br />

needs only one good work in order to establish his reputation’, Rodin<br />

returned to Brussels determined to create that sculpture.The shock <strong>of</strong><br />

defeat in the recent war and the more serious tone <strong>of</strong> the Third<br />

3

4<br />

‘I place the model in such a way<br />

that it stands out against the<br />

background and so that the light<br />

falls on this pr<strong>of</strong>ile. I execute it,<br />

and move both my turntable<br />

and that <strong>of</strong> the model, so that I<br />

can see another pr<strong>of</strong>ile.Then I<br />

turn them again, and gradually<br />

work my way around the figure.’<br />

RODIN<br />

Republic created a demand for sculptural monuments that <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

some sense <strong>of</strong> consolation to the nation. Rodin’s figure was originally<br />

called The Vanquished, and he began work with a Belgian soldier,<br />

Augustus Neyt, as his model. He had developed a system <strong>of</strong> modelling<br />

that depended on recording a clear outline <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> a figure<br />

seen from as many angles as was felt necessary.<br />

Rodin interrupted work on his figure by making a trip to Italy in<br />

early 1876.There he saw not only antique sculpture but the work <strong>of</strong><br />

Donatello (1386–1466), Michelangelo (1475–1564) and other Italian<br />

sculptors. Recalling his experience <strong>of</strong> Michelangelo’s Medici Tombs he<br />

said ‘we notice that his sculpture expresses the painful withdrawal <strong>of</strong><br />

the being into himself, restless energy.’This was in contrast to the<br />

‘quietude, grace, balance, reason’ <strong>of</strong> antique art.<br />

Originally conceiving the sculpture with a spear in the raised<br />

arm to suggest a vanquished soldier sensing the meaning <strong>of</strong> defeat,<br />

Rodin removed this accessory shortly before showing the work in<br />

Brussels. Deprived <strong>of</strong> this clue to its meaning, a critic asked:‘can this<br />

be a statue <strong>of</strong> a sleep walker?’ For its showing in Paris Rodin<br />

changed the title, making reference to the classical third stage<br />

<strong>of</strong> man’s development.<br />

Cat. 11 The pose, with arm raised to head, owes something to<br />

Michelangelo’s Dying Slave in the Louvre, but with the weight firmly<br />

on his left foot the figure has a classical balance and poise.What is<br />

remarkable is the supple and smoothly modelled transitions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

various parts <strong>of</strong> the body, like the feeling <strong>of</strong> the rib cage giving way to<br />

the stomach and then to the gentle curve <strong>of</strong> the belly. Neyt wrote that<br />

‘Rodin did not want any exaggerated muscle, he wanted naturalness’ –<br />

a naturalness that is brought to life by the way in which the delicately<br />

moulded surfaces reflect the light in a discontinuous fashion.<br />

How does Rodin create a sense <strong>of</strong> imminent movement?<br />

Given that the best points <strong>of</strong> view are from the front and to the spectator’s<br />

right, why might Rodin have removed the spear?<br />

The Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), who was briefly<br />

Rodin’s secretary, wrote most sensitively about the emotional qualities<br />

<strong>of</strong> his sculpture.‘That which was expressed in the face, that pain <strong>of</strong> a<br />

heavy awakening and at the same time the longing for that awakening,<br />

was written on the smallest part <strong>of</strong> this body. Every part was a mouth<br />

that spoke a language <strong>of</strong> its own.’<br />

Critics at the Salon were less acute, referring to ‘a curious atelier<br />

study with a very pretentious name.’The most damning accusation<br />

claimed that the figure was a cast from life. Rodin protested vigorously,<br />

ordering photographs <strong>of</strong> Neyt in the pose so comparisons could be<br />

made, along with written statements <strong>of</strong> the time involved, and even an<br />

actual cast. In one sense the furore attracted attention to the unknown<br />

thirty-seven-year-old and brought him supporters as well as detractors.<br />

THE GATES OF HELL<br />

Rodin’s problems over The Age <strong>of</strong> Bronze had one marvellous<br />

consequence. Edmund Turquet, a member <strong>of</strong> the committee<br />

investigating the charge <strong>of</strong> casting from life, had been made Undersecretary<br />

for Fine <strong>Arts</strong> in 1879. Early in the following year he discussed<br />

with Rodin the possible commission <strong>of</strong> a set <strong>of</strong> monumental doors for<br />

the proposed Museum <strong>of</strong> Decorative Art. Rodin suggested a theme<br />

based on the Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s (1265–1321) Inferno that<br />

would be expressed through many small figures in low relief. Rodin had<br />

been encouraged to read poetry at the Petit Ecole and Dante had<br />

already exerted a pr<strong>of</strong>ound influence on French Romantic artists. His<br />

proposal was accepted and in July <strong>of</strong> 1880 he moved into a<br />

government studio at the Dépôt des Marbres on the rue de<br />

l’Université and began work on a project that completely changed his<br />

way <strong>of</strong> making sculpture and whose influence would last for the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

his life.<br />

The Inferno is the first part <strong>of</strong> Dante’s Divine Comedy, a description<br />

<strong>of</strong> hell seen as a series <strong>of</strong> descending circles in which different<br />

categories <strong>of</strong> crimes and their eternal punishments are illustrated<br />

through his encounters with individual sinners. It is uncertain whether<br />

Rodin intended to reflect the stories and structure <strong>of</strong> the Inferno or<br />

rather to conjure up the words <strong>of</strong> Dante’s guide, the Roman poet Virgil<br />

(70–19 BC):<br />

‘Through me you go into the city <strong>of</strong> weeping;<br />

Through me you go into eternal pain;<br />

Through me you go among the lost people.’<br />

In the end Rodin used only two identifiable groupings,<br />

the adulterous lovers Paolo and Francesca (The Kiss), and<br />

Count Ugolino, betrayer <strong>of</strong> Pisa, starved into committing<br />

cannibalism on his sons and grandsons. Ugolino can be<br />

seen in fig. 1, one <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> imaginative drawings in<br />

which Rodin explored ‘the spirit <strong>of</strong> this remarkable poet’,<br />

whose expression he felt ‘is always primitive and<br />

sculptural.’ Using pencil, followed by Indian ink to<br />

strengthen the outlines and create a sense <strong>of</strong> mass,<br />

Rodin adds gouache to emphasise the sculptural effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> raking light. Dealing with themes <strong>of</strong> anguish, struggle<br />

and confinement, these drawings frequently have a<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> claustrophobic intensity as Rodin explores<br />

a vocabulary <strong>of</strong> gesture and form, that while not directly<br />

related to individual sculptures, helped to influence the<br />

overall conception. But, as he told a journalist in 1900:<br />

‘I realised that my drawings were too far removed<br />

from reality. I started all over again and worked from<br />

life with models.’<br />

Rodin was financially free to employ as many models<br />

as he liked, and they were encouraged to roam the<br />

studio, taking up poses while Rodin modelled in clay<br />

those that caught his imagination. He frequently stated<br />

that ‘Nature’ was the source <strong>of</strong> his inspiration, but at the<br />

Fig.1<br />

Ugolino, also called Ugolino First Day,<br />

c.1880<br />

Graphite, pen, brown wash and<br />

gouache on cream-coloured paper<br />

19.3 x 12 cm<br />

Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon, D. 9393<br />

Photo © Musée Rodin/Jean de Calan<br />

5

6<br />

Cat. 80<br />

Crouching Woman, c.1881–82<br />

Plaster<br />

31.9 x 28.7 x 21.1 cm<br />

Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon, S. 2396. Donation Rodin, 1916<br />

Photo © Musée Rodin/Christian Baraja<br />

‘A model may suggest, or<br />

awaken and bring to a<br />

conclusion, by a movement or a<br />

position, a composition that lies<br />

dormant in the mind <strong>of</strong> the<br />

artist … A model is, therefore,<br />

more than a means whereby the<br />

artist expresses a sentiment,<br />

thought or experience; it is a<br />

correlative inspiration to him.<br />

They work together as a<br />

productive force.’<br />

RODIN, 1889<br />

back <strong>of</strong> his mind were the teeming figure compositions <strong>of</strong> French<br />

Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Théodore<br />

Gericault (1791–1824) whose violent treatment <strong>of</strong> the human body he<br />

sought to emulate. Also present was Rodin’s obsession with human<br />

sexuality, sometimes ecstatic, sometimes painful, revealed in his growing<br />

command <strong>of</strong> the expressive shapes <strong>of</strong> the body.<br />

Cat. 80 In this early sculpture the human anatomy has been<br />

compressed into a tight ball.There is a strain sensed in knees, shoulder<br />

and neck as the body pushes open the thighs to create a totally<br />

uninhibited female pose.The hand grasping her foot may be seen as a<br />

defensive gesture enclosing the body, but also refers to a French idiom<br />

for orgasm.The other hand pressing her breast might be seen as<br />

suggestive <strong>of</strong> a frustrated maternal role, a child lost or denied by the<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> transgression that fills the lowered face.<br />

Which part <strong>of</strong> the anatomy creates the most expressive tension?<br />

Rodin frequently combined two figures to create a new sculptural unity.<br />

Imagine what kind <strong>of</strong> figure might go with Crouching Woman.<br />

In The Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell Rodin was working with five architectural units: the<br />

two side pilasters that form the framework <strong>of</strong> the doors, the two door<br />

panels themselves and above these a rectangular space or tympanum.<br />

Initial plans to divide each door into four separate compartments,<br />

which might have contained individual episodes from the Inferno, were<br />

abandoned for the open spaces in which Rodin could fit the growing<br />

number <strong>of</strong> small figures according to compositional necessity and<br />

emotional effect. At either side <strong>of</strong> the gates he proposed two life-size<br />

figures, Adam and Eve, both influenced by Michelangelo’s painted<br />

figures on the Sistine ceiling. Adam, already sculpted before the<br />

commission, dragging himself into life, and Eve, at the moment <strong>of</strong><br />

realising the consequences <strong>of</strong> her action.There are some similarities<br />

between Adam and the figure <strong>of</strong> The Shade, which seen from three<br />

different angles forms the group above the tympanum.The downward<br />

thrust <strong>of</strong> their arms and the depressed position <strong>of</strong> their heads are<br />

linked to Dante’s inscription ‘Abandon all hope’, and they lead us down<br />

to The Thinker.<br />

This figure has become synonymous with Rodin, its strong<br />

physicality conveying the struggle <strong>of</strong> contemplation and the forceful<br />

effort <strong>of</strong> creative endeavour. Starting out as a possible representation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Dante surveying his vision <strong>of</strong> hell, the figure’s meaning for Rodin<br />

changed as his intentions for The Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell broadened and his<br />

themes became more contemporary.The poet and novelist Victor<br />

Hugo (1802–1885) had explored the image <strong>of</strong> a poet–thinker<br />

contemplating a scene <strong>of</strong> chaos, and Charles Baudelaire’s (1821–1867)<br />

Les Fleurs du Mal lay open in the studio. In its Dante-esque vision <strong>of</strong><br />

modern Parisian life, Baudelaire’s poetry explored his attraction to evil<br />

and vice and his struggle with feelings <strong>of</strong> isolation, melancholy and<br />

boredom. Ultimately, The Thinker, especially in its independent life, can<br />

best be seen as an image <strong>of</strong> Rodin himself, embodying a nineteenthcentury<br />

Romantic concept <strong>of</strong> the genius–creator.

While Rodin said that there was ‘no scheme <strong>of</strong> illustration or<br />

intended moral purpose’, his work expresses a view <strong>of</strong> the spiritual<br />

state <strong>of</strong> his time and conforms with his belief that works <strong>of</strong> art ‘say<br />

everything that one can say about man and the world. Besides, they<br />

make us understand that there is something else that one cannot<br />

know.’ It was Rilke who said that Rodin’s art was ‘to help a time whose<br />

misfortune was that all its conflicts lay in the invisible.’<br />

After four years <strong>of</strong> intense work on The Gates it became clear that<br />

the French Government was uncertain whether to build the museum<br />

that The Gates would have adorned. A completion date receded into<br />

the distance and Rodin, who was averse to finishing anything, may have<br />

been relieved. More work was done between 1887 and 1889 for a<br />

possible showing at the Exposition in honour <strong>of</strong> the centenary <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Revolution, and judging from comments by visitors to the studio and<br />

contemporary photographs, the major artistic decisions had been<br />

taken by that date. In fact the first public showing <strong>of</strong> a plaster cast <strong>of</strong><br />

The Gates did not take place until Rodin’s 1900 exhibition and then<br />

without many <strong>of</strong> the free-standing and high-relief figures.The first<br />

bronze cast was made in 1926, by the director <strong>of</strong> the Rodin Museum.<br />

Cat. 95 Faced with the seven-metre-high The Gates, we find it hard to<br />

take in such a structure in its entirety, let alone appreciate much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

detail. Nevertheless, Rodin has orchestrated his vast canvas in ways that<br />

help us follow his composition. Starting in the tympanum, dominated by<br />

The Thinker, the movement is horizontal, from the figures on the left<br />

awaiting judgement to those on the right who have been judged.<br />

Crouching Woman is tucked in just to the left <strong>of</strong> The Thinker, tilted<br />

sideways, with her gaze directed at the Falling Man, that extraordinary<br />

figure that plunges us into the maelstrom <strong>of</strong> swirling bodies that make<br />

up the main doors. Here movement is downwards and diagonal and<br />

takes us to some <strong>of</strong> the major figure groupings such as Ugolino and his<br />

sons on the left-hand door, and below them Rodin’s revised<br />

representation <strong>of</strong> Paolo and Francesca, following his decision not to use<br />

The Kiss. In the two pilasters the sense <strong>of</strong> movement is upwards, with<br />

figures struggling to escape their fate.<br />

At the top right we find Crouching Woman born al<strong>of</strong>t by a revised<br />

version <strong>of</strong> Falling Man. Originally called The Rape, this combination <strong>of</strong><br />

figures became known as Je Suis Belle after the first line <strong>of</strong> a Baudelaire<br />

poem:‘I am beautiful as a dream <strong>of</strong> stone; but not maternal.’ Much <strong>of</strong><br />

the rhythm <strong>of</strong> the figure compositions <strong>of</strong> The Gates comes from the<br />

contrast between figures contracted into themselves and those<br />

stretched out, grasping for something external.<br />

In the two doors, how does Rodin’s use <strong>of</strong> the empty spaces help us read<br />

the composition <strong>of</strong> figures?<br />

How has Rodin used shadow and highlight, recession and projection in the<br />

different parts <strong>of</strong> The Gates?<br />

‘The Thinker in his austere nudity,<br />

in his pensive force, is at the<br />

same time a wild Adam,<br />

implacable Dante, and merciful<br />

Virgil … but he is above all The<br />

Ancestor, the first man, naive<br />

and without conscience, bending<br />

over that which he will<br />

engender.’<br />

OCTAVE MIRBEAU, 1918<br />

Cat. 95<br />

The Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell, c.1890<br />

Bronze, cast by Alexis Rudier<br />

680 x 400 x 85 cm<br />

Kunsthaus Zürich, 1949/22. Acquired in 1947<br />

Photo © 2006 Kunsthaus Zürich. All rights reserved.<br />

‘For him, the position <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human body could not be<br />

reduced to a few types. Rather<br />

they seemed to be infinite, all<br />

giving rise to new ones through<br />

the decomposition and recomposition<br />

<strong>of</strong> movements,<br />

multiplying in fleeting aspects<br />

each time the body shifts.’<br />

GUSTAVE GEFFROY, 1889<br />

9

10<br />

Cat. 132<br />

Pierre de Wissant, Monumental Nude, 1886<br />

Bronze<br />

193 x 115 x 95 cm<br />

Kunstverein Winterthur. Presented on the 100th<br />

anniversary <strong>of</strong> the Kunstverein Winterthur by<br />

Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft AG, J.J Rieter & Cie,<br />

Gebrüder Sulzer AG, Schweizerische<br />

Unfallversicherungsgesellschaft Winterthur, 1948<br />

Photo © Kunstmuseum Winterthur<br />

‘His right arm is raised, bent,<br />

vacillating. His hand opens in the<br />

air as though to let something<br />

go, as one gives freedom to a<br />

bird.This gesture is symbolic <strong>of</strong><br />

a departure from all uncertainty,<br />

from a happiness that has not<br />

yet been, from a grief that<br />

will now wait in vain …<br />

a monument for all who<br />

have died young.’<br />

RAINER MARIA RILKE, 1903<br />

RODIN’S STUDIO<br />

Rodin employed assistants to make moulds and multiple plaster casts<br />

<strong>of</strong> his clay originals. Using these to alter, recombine or cut up, Rodin<br />

continued to refine his ideas. In later years specialist craftsmen, using a<br />

compass like tool, would scale up figures that needed to be enlarged to<br />

life size, arriving at a finished plaster version that became the ‘master’<br />

for a bronze cast, or marble carving if a client was prepared to pay for<br />

one. Much <strong>of</strong> this work was undertaken by quite well-known sculptors<br />

like Antoine Bourdelle and Victor Peter in their own studios.<br />

In the nineteenth century, sculpture was largely a reproductive art<br />

and the distinction between ‘original’ and ‘copy’ only became relevant<br />

when the casting or carving failed to live up to the original plaster.<br />

Occasionally Rodin approved large editions in different sizes <strong>of</strong> a<br />

popular work. Foundries produced four different-sized versions <strong>of</strong> The<br />

Kiss, based on the enlarged marble version, making over 300 copies,<br />

some <strong>of</strong> dubious quality and completely lacking the subtlety <strong>of</strong><br />

unfolding drama present in the plaster version (cat. 25). After Rodin’s<br />

death, the Rodin Museum assumed responsibility for all casts made<br />

from plaster originals.<br />

THE BURGHERS OF CALAIS<br />

In 1884 the city <strong>of</strong> Calais decided to commemorate the heroism <strong>of</strong><br />

Eustache de St Pierre, a leading citizen and the first <strong>of</strong> six volunteers<br />

who agreed to sacrifice their lives to lift the siege that the English king,<br />

Edward III, had laid against the city in 1346. Jean Froissart, who served<br />

Edward’s French wife, described in his Chronicle Eustache de St Pierre’s<br />

response to the king’s demand for hostages:‘great mischief it should be,<br />

to suffer to die such people as be in this town … when there is means<br />

to save them … wherefore, to save them I will be the first to put my<br />

life in jeopardy.’<br />

Sensing that a group sculpture would provide more variety <strong>of</strong><br />

posture, movement, gesture and emotional response, Rodin prepared a<br />

maquette with all six burghers included. Acknowledging that ‘a heroic<br />

conception’ was needed, he may also have felt that a group portrait<br />

would encourage a communal response more in line with Republican<br />

ideals. After the presentation <strong>of</strong> a second maquette it was clear that<br />

the committee in charge <strong>of</strong> the project had other ideas.‘This is not<br />

how we visualised our illustrious fellow-citizens.Their dejected attitude<br />

militates against our beliefs.’What they wanted was a more<br />

conventional ‘pyramid’-shaped monument that would raise Eustache de<br />

St Pierre above his companions to create a more positive impression.<br />

Rodin rejected their criticisms and continued working on a series <strong>of</strong><br />

individual studies <strong>of</strong> each burgher.<br />

It was common nineteenth-century practice to make nude figures<br />

to establish the physical validity <strong>of</strong> a chosen pose before going on to<br />

the clothed version.‘You will see that it is what one does not see which<br />

is the principal thing’ was Rodin’s justification for the enormous amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> work involved. He started working at a third life-size and scaled up<br />

his figures as he became satisfied. Separate studies <strong>of</strong> heads, hands and<br />

11

12<br />

Cat. 123<br />

The Burghers <strong>of</strong> Calais, 1908<br />

Bronze<br />

231 x 245 x 200 cm<br />

Presented to the nation by The Art Fund, 1914. Restored<br />

and set on a new plinth in Victoria Tower Gardens through<br />

the generosity <strong>of</strong> Nicholas and Judith Goodison, 2004.<br />

Loaned by The <strong>Royal</strong> Parks.<br />

Photo The <strong>Royal</strong> Parks/Roy Fox<br />

feet were done and these could be attached to the body to<br />

experiment with expression and gesture. He had been to Calais to<br />

sketch and study local physiognomies, and while this may suggest a<br />

‘naturalistic’ approach, what strikes us is the imaginative leap that Rodin<br />

made to enter into the emotional response <strong>of</strong> each burgher as they<br />

contemplated their fate.<br />

Cat. 132 Seen from the front <strong>of</strong> the final monument Pierre de Wissant<br />

stands to the left <strong>of</strong> Eustache de St Pierre. His fragile, youthful body<br />

with its turning, sinuous shape and freely expressive arms contrasts<br />

strongly with the heavy strength <strong>of</strong> Eustache de St Pierre and his other<br />

neighbour, Jean d’Aire, who carries a key to the city. In an almost dancelike<br />

pose, Rodin conjures up a sense <strong>of</strong> hesitant advance as the bent,<br />

bony leg prepares to move forward, while the raised hand, with spread<br />

fingers, plucks a gesture <strong>of</strong> farewell from the lowered head.<br />

How does the alignment <strong>of</strong> hips and shoulders convey the sense <strong>of</strong><br />

movement?<br />

In his 1900 exhibition Rodin placed this statue at the very entrance, but<br />

without the hands or head. How would this change it’s meaning and how<br />

would you read it?<br />

In 1886, the financial collapse <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the Calais banks<br />

responsible for raising money for the monument and difficulties with<br />

the committee led to delays in completion. Rodin showed the full-sized<br />

plaster cast in 1889 at an exhibition held jointly with Claude Monet<br />

(1840–1926), but it was not till 1895 that the monument was erected<br />

in Calais. In the intervening years Rodin had toyed with various<br />

possibilities for displaying his work. At one time he favoured a groundlevel<br />

installation, strung out in front <strong>of</strong> the Hôtel de Ville, so that<br />

‘passers-by would have elbowed them, and they would have felt<br />

through this contact the emotion <strong>of</strong> the living past in their midst’.<br />

Rodin had the opportunity to try out another idea for its display<br />

when the National Art Collections Fund in England purchased a cast in<br />

1911. Harking back to raised equestrian monuments in Venice and<br />

Padua, he hoped to place The Burghers directly in front <strong>of</strong> the Houses<br />

<strong>of</strong> Parliament, silhouetted against the sky. In the end. The Burghers were<br />

placed on a fifteen-foot-high plinth in nearby Victoria Gardens. In<br />

response to public demand the plinth was removed in 1956.<br />

Cat. 124 The Burghers <strong>of</strong> Calais invite the passage <strong>of</strong> time.What Rodin<br />

is proposing is the slow movement past us <strong>of</strong> six individuals wrapped in<br />

their own private reaction to approaching death. Of course it is the<br />

spectator who has to move to reveal the unfolding drama. As we<br />

proceed to walk around, Rodin lays out his individual characters in<br />

pairs, trios and even a quartet, allowing us to compare and contrast the<br />

reactions <strong>of</strong> stoic determination, defiance, despair, resignation, protest<br />

and fear.The heavy fall <strong>of</strong> drapery with its deep recessions and<br />

projections creates a unifying rhythm that binds the group together.<br />

The hands and feet are much enlarged.Was Rodin doing this because the<br />

figures might be seen at a distance? Or was the exaggeration for artistic<br />

purposes?<br />

In his treatment <strong>of</strong> Pierre de Wissant’s clothing, how has Rodin preserved<br />

the fragile nature <strong>of</strong> his body?<br />

THE STATUE OF BALZAC<br />

In 1891 the Société des Gens de Lettres approached Rodin with a<br />

commission to sculpt a statue <strong>of</strong> the novelist Honoré de Balzac<br />

(1799–1850), author <strong>of</strong> the Comédie Humane, a series <strong>of</strong> interconnected<br />

novels that examined French society with an almost<br />

scientific precision.The committee’s original choice <strong>of</strong> sculptor had died<br />

without completing his work, and the chairman, Emile Zola<br />

(1840–1902), may have had difficulty in persuading them to award<br />

Rodin the commission by twelve votes to eight.To set a time limit <strong>of</strong><br />

eighteen months for the notoriously over-worked sculptor, already<br />

grappling with a monument to Victor Hugo, was also asking for trouble.<br />

‘Balzac is before everything a creator and this is the idea I would<br />

wish to make understood in my statue … As <strong>of</strong> now I would want to<br />

execute a figure standing rather than seated.’ Rodin’s initial response<br />

went straight to the heart <strong>of</strong> the matter, but the process <strong>of</strong><br />

investigation and experimentation would be as long drawn out as in his<br />

other major projects. Balzac had been dead for over forty years, but<br />

there were portraits, daguerreotypes and caricatures that Rodin could<br />

draw on.Visiting Balzac’s home town <strong>of</strong> Tours, he found a coachman<br />

who resembled the author, and ordered a suit <strong>of</strong> clothes from Balzac’s<br />

‘The figures do not touch one<br />

another, but stand side by side<br />

like the last trees <strong>of</strong> a hewndown<br />

forest united only by the<br />

surrounding atmosphere. From<br />

every point <strong>of</strong> view the gestures<br />

stand out clear and great from<br />

the dashing waves <strong>of</strong> the<br />

contours; they rise and fall back<br />

into the mass <strong>of</strong> stone [sic] like<br />

flags that are furled.’<br />

RAINER MARIA RILKE, 1903<br />

13

14<br />

Cat. 143<br />

Balzac, Study <strong>of</strong> Nude ‘C’, c.1894<br />

Plaster<br />

129 x 62 x 52 cm<br />

Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon, S. 177. Donation Rodin, 1916<br />

Photo © Musée Rodin/Adam Rzepka<br />

‘It has always astonished me that<br />

Balzac owes his fame to the fact<br />

that he passed for an observer.<br />

To me it has always seemed that<br />

his chief merit lies in his having<br />

been a visionary, and an<br />

impassioned visionary. All his<br />

characters are endowed with<br />

the blazing vitality that he himself<br />

possessed.’<br />

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE<br />

Fig.2<br />

EDWARD STEICHEN<br />

Toward the Light–Midnight (Balzac on the<br />

grounds <strong>of</strong> Meudon), c.1908<br />

Gum Platinotype<br />

19 x 21.3 cm<br />

Private collection<br />

tailor.This approach to the physical reality <strong>of</strong> the man was as important<br />

for Rodin as was the reading <strong>of</strong> the novels. Rather than seeing the<br />

many ‘Balzacs’ as studies towards a final sculptural figure, it might be<br />

best to view them as a continuous biography exploring different<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> the man and writer.<br />

Cat. 143 In this nude study Rodin takes Balzac’s physical defects, his<br />

short, overweight and ugly features, and turns them into something<br />

heroic and rather touching. Balzac’s biographer had used the phrase<br />

‘courageous athlete’ and there is something <strong>of</strong> that in this stance.The<br />

striding legs exude a sense <strong>of</strong> confidence.The arms crossed over the<br />

protruding belly both absorb that mass into the body and derive their<br />

strength from it.The powerful shoulders mirror the belly and lead up<br />

to the short squat neck. Balzac was known as a public speaker, and the<br />

facial expression conveys the determination <strong>of</strong> a man prepared to<br />

overcome his physical awkwardness with the force <strong>of</strong> personality and<br />

wit.<br />

Would you say that the size <strong>of</strong> head and body matched each other?<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the studies <strong>of</strong> Balzac show him with a flowing mane <strong>of</strong> hair.Why<br />

do think Rodin has suppressed this aspect?<br />

Rodin’s problems with the committee, his own over-work, and<br />

occasional periods <strong>of</strong> depression following the end <strong>of</strong> his relationship<br />

with Camille Claudel meant that the final Balzac monument was not<br />

unveiled until 1898. Based on a nude study <strong>of</strong> Jean d’Aire with hands<br />

grasping his genitals, this figure, wrapped in the dressing gown in which<br />

Balzac worked, rises with its simplified shapes to the monumental head<br />

with its powerful sense <strong>of</strong> a visionary sexual and creative power.<br />

Rejected by the committee, it was only cast and erected by the city <strong>of</strong><br />

Paris in 1939, when its dedication to both Balzac and Rodin<br />

acknowledged their equal status and the sense <strong>of</strong> identification that<br />

had overtaken the sculptor.<br />

RODIN AND PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Rodin was working at a period when<br />

photography replaced the traditional<br />

engraving or print as a means <strong>of</strong><br />

disseminating artistic images. He took it<br />

seriously, instructing photographers in the<br />

most appropriate points <strong>of</strong> view and lighting<br />

conditions. Photographs provided him with a<br />

detached viewpoint <strong>of</strong> his work that he<br />

could use to consider and reconsider,<br />

frequently drawing over figures to indicate<br />

potential changes.<br />

It was Rodin’s idea to get Edward<br />

Steichen (1879–1973) to capture the plaster<br />

cast <strong>of</strong> Balzac by moonlight (fig. 2) , creating a

16<br />

‘Less a statue than a kind <strong>of</strong><br />

strange monolith, an age-old<br />

menhir, one <strong>of</strong> those rocks on<br />

which the caprice <strong>of</strong> some<br />

prehistoric volcanic explosion<br />

has etched a human face<br />

by chance.’<br />

GEORGES RODENBACH, 1898.<br />

Cat. 160<br />

The Earth and the Moon, 1898–99<br />

Marble<br />

122.5 x 72.5 x 65 cm<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong> Wales, NMW A 2509.<br />

Bequeathed by Gwendoline David, 1940<br />

Photo © National Museum <strong>of</strong> Wales<br />

moody, symbolist image that emphasises Rodin’s link with that<br />

movement.‘You will make the world understand my Balzac through<br />

these pictures.They are like Christ walking in the Desert.’<br />

THE MARBLE SCULPTURES<br />

In the twentieth century Rodin’s marble sculptures have been<br />

negatively criticised on the grounds that he didn’t make them. Rodin<br />

modelled in clay and while he regarded plaster as the most appropriate<br />

material for the development <strong>of</strong> his ideas and display in exhibitions,<br />

bronze and marble were seen as the most permanent materials with<br />

commercial potential. Although Rodin did not carve the marble<br />

versions himself, he certainly supervised the output <strong>of</strong> the many skilled<br />

carvers who worked for him, <strong>of</strong>ten in their own studios.<br />

Rodin had built up a vast collection <strong>of</strong> figures and objects from all<br />

over the world and from many different periods. Naturally there were<br />

many Roman marble copies <strong>of</strong> Greek works, and he admired the<br />

limpid, transparent quality <strong>of</strong> the stone, its variety <strong>of</strong> colour and the<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> achieving a silky smooth finish that made it ideal for one<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> representation <strong>of</strong> human flesh.This could be particularly<br />

effective in his later portraits <strong>of</strong> women where the smoothly modelled<br />

features have a veiled, almost dream like quality in contrast to the<br />

rougher unfinished surroundings.<br />

Cat. 160 Rodin’s marble sculptures <strong>of</strong> the 1890s, using single or newly<br />

combined small figures from The Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell or after, frequently carry<br />

classical titles or vaguer symbolic ones. For the sculptor it was the<br />

formal relationship <strong>of</strong> the figures to the block <strong>of</strong> marble they would be<br />

embedded in that came first. A contrast is made between the smoothly<br />

carved figures and the varied rougher, non-finito treatment <strong>of</strong> the stone,<br />

which suggests an environment that the spectator is free to interpret.<br />

The title <strong>of</strong> this work, The Earth and The Moon, invites us to transpose<br />

the large marble block, with its many types <strong>of</strong> mark, into some kind <strong>of</strong><br />

cosmic space inhabited by the figures, drawn together by a force <strong>of</strong><br />

erotic gravity.<br />

How has Rodin created a sensation <strong>of</strong> floating?<br />

THE LATE DRAWINGS<br />

From about 1895 Rodin resumed the practice <strong>of</strong> drawing, working<br />

exclusively from the model. Faced with the many demands to oversee<br />

reproductions <strong>of</strong> his work, this essentially personal activity enabled him<br />

to escape the quasi-industrial aspect <strong>of</strong> his studio and work without<br />

assistance. In over 7,000 sheets he obsessively recorded the female<br />

body with models whose poses flagrantly explored different aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

female sexuality. Concentrating entirely on the figure and with no sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> studio context, the five-foot-seven-inch, short-sighted artist adopted<br />

a close vantage-point and drew rapidly with a continuous flow <strong>of</strong> the<br />

pencil. He never took his eyes <strong>of</strong>f the model and this mode <strong>of</strong> working<br />

17

18<br />

became a way <strong>of</strong> sustaining the emotions inspired by her body.To<br />

some he would later add a pale wash to bring out a sense <strong>of</strong> volume<br />

and differentiate the figure from the background, <strong>of</strong>ten cutting out and<br />

re-pasting the isolated figure on a new piece <strong>of</strong> paper or combining it<br />

with another drawing.<br />

Cat. 265 Rodin was fascinated by movement and its sense <strong>of</strong> implied<br />

action. In this study <strong>of</strong> a woman with her arms crossed, the pose owes<br />

much to his love <strong>of</strong> dance, particularly the more formal and restrained<br />

movements <strong>of</strong> Oriental dancers.The curving arabesque from her<br />

lowered left shoulder down to waist and buttock and thigh provides<br />

the pivotal force <strong>of</strong> energy reflected in the swelling belly and raised<br />

arms.<br />

The model appears to be wearing a cape, which billows out to right and<br />

left. Do you think she was actually wearing one or do you think that Rodin<br />

added it, along with the fluid lines across and around her thighs, to suggest<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> movement implicit in the pose?<br />

The late drawings can be seen as a celebration <strong>of</strong> feminine sexuality.What<br />

might have been the reaction if one reversed the gender <strong>of</strong> artist and<br />

model?<br />

THE PARTIAL FIGURES<br />

Rodin felt that one part <strong>of</strong> the sculpture, usually the torso, contained<br />

the core <strong>of</strong> energy that radiated out into the rest <strong>of</strong> the figure, and it<br />

was not unusual for him to make studies <strong>of</strong> only part <strong>of</strong> the figure.<br />

Given his propensity to mix and match, using one part <strong>of</strong> a figure<br />

combined with part <strong>of</strong> another, the idea <strong>of</strong> sculptural form as a direct<br />

representation <strong>of</strong> nature was subverted in favour <strong>of</strong> artistic<br />

manipulation. Rodin felt free to exhibit his studies as well as radically<br />

altering existing figures by the removal <strong>of</strong> extremities.<br />

Cat. 205 This figure, known as The Muse,The Inner Voice or Meditation,<br />

demonstrates how Rodin used and reused a figure in different ways,<br />

finding new creative possibilities over an extended period <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

Originally a small figure in the right-hand side <strong>of</strong> the tympanum <strong>of</strong> The<br />

Gates <strong>of</strong> Hell, she can be seen with that characteristic twist <strong>of</strong> the body,<br />

head lowered and her right hand touching her hair. Detached from The<br />

Gates and enlarged, the right hand now cradles the face and the left<br />

hand touches the upper breast. It has been suggested that the<br />

inspiration for the sculpture was Camille Claudel’s body and attitude,<br />

which may account for its use in a proposed monument to Victor<br />

Hugo as one <strong>of</strong> three muses, initially with the arms but later without,<br />

and with the knee and upper leg covered in drapery. By severing this<br />

drapery Rodin arrived at the figure before us.<br />

The calm, classical head suggests an antique Venus, while the<br />

torsion in the pose <strong>of</strong> the body reminds us more <strong>of</strong> Michelangelo.<br />

Removal <strong>of</strong> the arms has created a more flowing, continuous silhouette<br />

and opens up the face to light.The feeling is <strong>of</strong> withdrawal into the self;<br />

Cat. 265<br />

Woman with Folded Arms and Flexed Legs<br />

Dancing with Fluttering Veils, c. 1898<br />

Graphite and stump on cream-coloured<br />

paper<br />

30.6 x 19.9 cm<br />

Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon, D. 2363. Donation Rodin,<br />

1916<br />

Photo © Musée Rodin/Jean de Calan<br />

‘A work <strong>of</strong> art is always noble,<br />

even when it translates the<br />

stirrings <strong>of</strong> the brute, for at that<br />

moment the artist who has<br />

produced it had as his only<br />

objective the most conscientious<br />

rendering possible <strong>of</strong> the<br />

impression he has felt.’<br />

RODIN, 1907<br />

19

20<br />

Cat. 205<br />

Muse, also called Meditation and The Inner<br />

Voice, 1896<br />

Bronze<br />

144.5 x 75 x 54 cm<br />

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, A36-1914. Rodin<br />

Donation, 1914<br />

Photo © V&A Images/V&A Museum<br />

‘The way in which the artist<br />

arrives at his goal is the secret <strong>of</strong><br />

his own existence. It is the<br />

measure <strong>of</strong> his own vision ….<br />

He exaggerates or deforms the<br />

literal in sculpture … He<br />

suppresses or diminishes one<br />

part; and yet the whole is true<br />

because he seeks only truth.’<br />

RODIN, 1906<br />

as though the whole central part <strong>of</strong> the body absorbs and protects the<br />

contemplation implicit in the face, which might otherwise have been<br />

dissipated by the presence <strong>of</strong> those parts that he has removed.<br />

Rodin has left the casting seams from the piece mould on the figure. Do<br />

they help us to feel the curvatures <strong>of</strong> the different volumes?<br />

Should we be disturbed by the anatomically impossible position <strong>of</strong> the<br />

head?<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Rodin was a giant <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century steeped in many <strong>of</strong> its<br />

Romantic and literary ideals, yet at the same time he had taken<br />

sculpture from being, in academic terms,‘a selective imitation <strong>of</strong> nature’<br />

to, in his own words, the art <strong>of</strong> the ‘hole and the lump’. Rodin had<br />

explored the emotional, expressive potential <strong>of</strong> the human head and<br />

figure as far as it could go, and we may find that the rhetorical,<br />

clamorous aspect <strong>of</strong> his work tips into an exaggerated pathos, or that<br />

the erotic slides into the sentimental. Sculptors escaping his shadow<br />

retreated into a calmer, more timeless serenity. Nevertheless, the<br />

revelation <strong>of</strong> his partial figures and the extraordinary range <strong>of</strong> his<br />

creative invention would live on long into the twentieth century.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Rodin, exh. cat., Catherine Lampert, Antoinette Le Normand-Romain,<br />

<strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>, London, 2006<br />

Rodin Rediscovered, exh. cat., Albert Elsen (ed.), National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Art,<br />

Washington, D.C., 1981<br />

CATHERINE LAMPERT, Rodin: Sculpture and Drawings, London, 1986<br />

ALBERT E. ELSEN, Rodin’s Art, Oxford, 2003