Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS BY JR/AGENCE VU EXCEPT PAGE 73 BY CAROLINE ELUYEMI/CAMERA PRESS/RETNA AND<br />

THIS PAGE (TOP RIGHT) BY ANDREW WINNING/REUTERS/LANDOV<br />

later, he was done, running down an<br />

alleyway before the police caught on.<br />

Soon, documenting his friends wasn’t<br />

enough. “Graffi ti was about the action,”<br />

says JR. “As I began to paste bigger<br />

pictures, I wanted more. And when I<br />

began going to other cities, it became<br />

about concept.”<br />

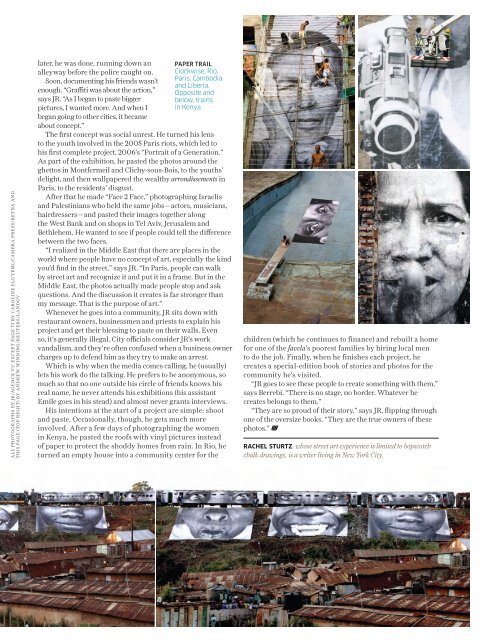

PAPER TRAIL<br />

Clockwise, Rio,<br />

Paris, Cambodia<br />

and Liberia.<br />

Opposite and<br />

below, trains<br />

in Kenya<br />

The fi rst concept was social unrest. He turned his lens<br />

to the youth involved in the 2005 Paris riots, which led to<br />

his fi rst complete project, 2006’s “Portrait of a Generation.”<br />

As part of the exhibition, he pasted the photos around the<br />

ghettos in Montfermeil and Clichy-sous-Bois, to the youths’<br />

delight, and then wallpapered the wealthy arrondissements in<br />

Paris, to the residents’ disgust.<br />

After that he made “Face 2 Face,” photographing Israelis<br />

and Palestinians who held the same jobs—actors, musicians,<br />

hairdressers—and pasted their images together along<br />

the West Bank and on shops in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and<br />

Bethlehem. He wanted to see if people could tell the diff erence<br />

between the two faces.<br />

“I realized in the Middle East that there are places in the<br />

world where people have no concept of art, especially the kind<br />

you’d fi nd in the street,” says JR. “In Paris, people can walk<br />

by street art and recognize it and put it in a frame. But in the<br />

Middle East, the photos actually made people stop and ask<br />

questions. And the discussion it creates is far stronger than<br />

my message. That is the purpose of art.”<br />

Whenever he goes into a community, JR sits down with<br />

restaurant owners, businessmen and priests to explain his<br />

project and get their blessing to paste on their walls. Even<br />

so, it’s generally illegal. City offi cials consider JR’s work<br />

vandalism, and they’re often confused when a business owner<br />

charges up to defend him as they try to make an arrest.<br />

Which is why when the media comes calling, he (usually)<br />

lets his work do the talking. He prefers to be anonymous, so<br />

much so that no one outside his circle of friends knows his<br />

real name, he never attends his exhibitions (his assistant<br />

Emile goes in his stead) and almost never grants interviews.<br />

His intentions at the start of a project are simple: shoot<br />

and paste. Occasionally, though, he gets much more<br />

involved. After a few days of photographing the women<br />

in Kenya, he pasted the roofs with vinyl pictures instead<br />

of paper to protect the shoddy homes from rain. In Rio, he<br />

turned an empty house into a community center for the<br />

children (which he continues to finance) and rebuilt a home<br />

for one of the favela’s poorest families by hiring local men<br />

to do the job. Finally, when he finishes each project, he<br />

creates a special-edition book of stories and photos for the<br />

community he’s visited.<br />

“JR goes to see these people to create something with them,”<br />

says Berrebi. “There is no stage, no border. Whatever he<br />

creates belongs to them.”<br />

“They are so proud of their story,” says JR, fl ipping through<br />

one of the oversize books. “They are the true owners of these<br />

photos.”<br />

RACHEL STURTZ, whose street art experience is limited to hopscotch<br />

chalk drawings, is a writer living in New York City.