DANGEROUS CROSSING: - International Campaign for Tibet

DANGEROUS CROSSING: - International Campaign for Tibet

DANGEROUS CROSSING: - International Campaign for Tibet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET<br />

The Situation <strong>for</strong> the Long-staying <strong>Tibet</strong>an Refugees in Nepal<br />

a) Legal status<br />

Although Nepal is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its<br />

1967 Protocol, it is bound by customary law to respect the principle of nonrefoulement<br />

or <strong>for</strong>cible repatriation. Until 1989 <strong>Tibet</strong>ans who had escaped<br />

from <strong>Tibet</strong> into Nepal were able to legally reside in Nepal, enjoying many of<br />

the rights of citizens. This came to an abrupt end in 1989. While no official<br />

reason was given at the time <strong>for</strong> Nepal to stop offering <strong>Tibet</strong>ans refuge, the<br />

timing of the sudden cut-off speaks volumes.<br />

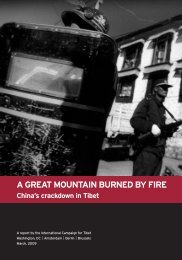

Throughout the 1980s, the situation in <strong>Tibet</strong> had become increasingly tense.<br />

Chinese government re<strong>for</strong>ms on the <strong>Tibet</strong>an plateau encouraged “thousands<br />

of unemployed [Chinese] migrants” to “drift into <strong>Tibet</strong> looking <strong>for</strong> work.” 151<br />

So started what became a population transfer policy designed to drastically<br />

change the demographics inside the <strong>Tibet</strong> Autonomous Region (TAR). In<br />

1987, the Dalai Lama released his 5-Point Peace Plan that called in part <strong>for</strong><br />

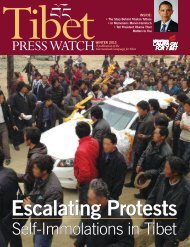

the cessation of such population transfer. As tensions rose in <strong>Tibet</strong>, a series<br />

of non-violent <strong>Tibet</strong>an protests were staged in Lhasa in 1987, ‘88 and ‘89,<br />

led by monks from the Drepung and Ganden monasteries. These were violently<br />

crushed by Chinese state security <strong>for</strong>ces and, after a protest on March<br />

4, 1989, the Chinese Party Secretary in the TAR, Hu Jintao, declared martial<br />

law in Lhasa. The severity of the post-protest crackdown <strong>for</strong>ced thousands of<br />

<strong>Tibet</strong>ans to cross the Himalayas into exile in Nepal – the largest number since<br />

the initial refugee exodus in the early 1960s. Although the Nepal government<br />

may well have been concerned about being able to cater to increasing numbers<br />

of refugees, it is highly likely that significant pressure from the Chinese<br />

government kept them from doing so. This apparent capitulation to Chinese<br />

demands was to set a precedent <strong>for</strong> the political relationship between the two<br />

governments.<br />

<strong>Tibet</strong>an refugees who had been living in Nepal were allowed to continue to<br />

do so but, after 1990 and <strong>for</strong> each subsequent year, the thousands of refugees<br />

who left <strong>Tibet</strong> seeking freedom in exile were denied refuge in Nepal. At<br />

this point, the UNHCR and the Nepal government entered into an in<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

Gentlemen’s Agreement providing <strong>for</strong> the safe passage of <strong>Tibet</strong>ans through<br />

Nepali territory onward to India. Incidents or threats of refoulement at the<br />

<strong>Tibet</strong>-Nepal border, and a lack of access or monitoring of the border by the<br />

UNHCR, has increased concerns that Chinese pressure could be outweighing<br />

Nepal’s commitment to the Gentleman’s Agreement. Such concerns have led<br />

to calls from the international community, in particular certain western em-<br />

57