xelovnebis saerTaSoriso Jurnali - Artisterium

xelovnebis saerTaSoriso Jurnali - Artisterium

xelovnebis saerTaSoriso Jurnali - Artisterium

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Nathaniel McBride<br />

0<br />

ART AND RISK<br />

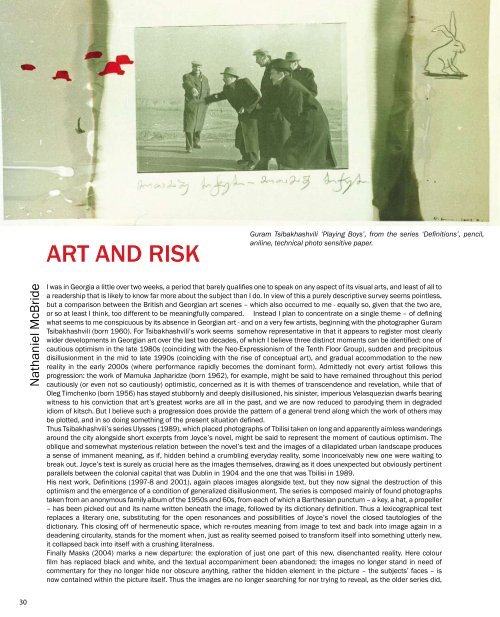

Guram Tsibakhashvili ‘Playing Boys’, from the series ‘Definitions’, pencil,<br />

aniline, technical photo sensitive paper.<br />

I was in Georgia a little over two weeks, a period that barely qualifies one to speak on any aspect of its visual arts, and least of all to<br />

a readership that is likely to know far more about the subject than I do. In view of this a purely descriptive survey seems pointless,<br />

but a comparison between the British and Georgian art scenes – which also occurred to me - equally so, given that the two are,<br />

or so at least I think, too different to be meaningfully compared. Instead I plan to concentrate on a single theme – of defining<br />

what seems to me conspicuous by its absence in Georgian art - and on a very few artists, beginning with the photographer Guram<br />

Tsibakhashvili (born 1960). For Tsibakhashvili’s work seems somehow representative in that it appears to register most clearly<br />

wider developments in Georgian art over the last two decades, of which I believe three distinct moments can be identified: one of<br />

cautious optimism in the late 1980s (coinciding with the Neo-Expressionism of the Tenth Floor Group), sudden and precipitous<br />

disillusionment in the mid to late 1990s (coinciding with the rise of conceptual art), and gradual accommodation to the new<br />

reality in the early 2000s (where performance rapidly becomes the dominant form). Admittedly not every artist follows this<br />

progression: the work of Mamuka Japharidze (born 1962), for example, might be said to have remained throughout this period<br />

cautiously (or even not so cautiously) optimistic, concerned as it is with themes of transcendence and revelation, while that of<br />

Oleg Timchenko (born 1956) has stayed stubbornly and deeply disillusioned, his sinister, imperious Velasquezian dwarfs bearing<br />

witness to his conviction that art’s greatest works are all in the past, and we are now reduced to parodying them in degraded<br />

idiom of kitsch. But I believe such a progression does provide the pattern of a general trend along which the work of others may<br />

be plotted, and in so doing something of the present situation defined.<br />

Thus Tsibakhashvili’s series Ulysses (1989), which placed photographs of Tbilisi taken on long and apparently aimless wanderings<br />

around the city alongside short excerpts from Joyce’s novel, might be said to represent the moment of cautious optimism. The<br />

oblique and somewhat mysterious relation between the novel’s text and the images of a dilapidated urban landscape produces<br />

a sense of immanent meaning, as if, hidden behind a crumbling everyday reality, some inconceivably new one were waiting to<br />

break out. Joyce’s text is surely as crucial here as the images themselves, drawing as it does unexpected but obviously pertinent<br />

parallels between the colonial capital that was Dublin in 1904 and the one that was Tbilisi in 1989.<br />

His next work, Definitions (1997-8 and 2001), again places images alongside text, but they now signal the destruction of this<br />

optimism and the emergence of a condition of generalized disillusionment. The series is composed mainly of found photographs<br />

taken from an anonymous family album of the 1950s and 60s, from each of which a Barthesian punctum – a key, a hat, a propeller<br />

– has been picked out and its name written beneath the image, followed by its dictionary definition. Thus a lexicographical text<br />

replaces a literary one, substituting for the open resonances and possibilities of Joyce’s novel the closed tautologies of the<br />

dictionary. This closing off of hermeneutic space, which re-routes meaning from image to text and back into image again in a<br />

deadening circularity, stands for the moment when, just as reality seemed poised to transform itself into something utterly new,<br />

it collapsed back into itself with a crushing literalness.<br />

Finally Masks (2004) marks a new departure: the exploration of just one part of this new, disenchanted reality. Here colour<br />

film has replaced black and white, and the textual accompaniment been abandoned; the images no longer stand in need of<br />

commentary for they no longer hide nor obscure anything, rather the hidden element in the picture – the subjects’ faces – is<br />

now contained within the picture itself. Thus the images are no longer searching for nor trying to reveal, as the older series did,