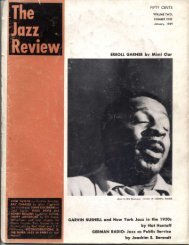

The Jazz Review - Jazz Studies Online

The Jazz Review - Jazz Studies Online

The Jazz Review - Jazz Studies Online

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

with anything better. <strong>The</strong> result is<br />

a stylistic vacuum, in which Madison<br />

Avenue jargon ("lusty satire showcasing<br />

Green's incomparable dirty<br />

tone") jostles the newspaperman's<br />

adjective-hunting, which seems so<br />

often a sort of condescension ("a<br />

dozen sides which remain among the<br />

most exhilarating small group work<br />

on disks"). <strong>The</strong> jazzmakers themselves<br />

are treated with a standard<br />

brand of tight-lipped sentimentality.<br />

But of course it is difficult to avoid<br />

the Ernest tone, even if it estranges<br />

the subject instead of bringing it<br />

closer.<br />

Along with what is weak or irritating,<br />

the book offers much that<br />

is good, especially when the musicians<br />

speak for themselves. Baby<br />

Dodds and Roy Eldridge sound off<br />

at length. Hentoff shepherds critics,<br />

promoters, musicians, and Lester<br />

Young through a most illuminating<br />

panel discussion of Lester Young.<br />

Charles Edward Smith contributes<br />

articles on Pee Wee Russell, Teagarden,<br />

and Billie. <strong>The</strong>se pieces are<br />

true evocations of personality: every<br />

rambling paragraph, moreover, exhibits<br />

the respect and affection of<br />

Smith for what he is dealing with.<br />

And isn't this first requisite of<br />

readable criticism?<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Jazz</strong> Makers was published last<br />

year by Rinehart and now reappears<br />

(with some different photographs)<br />

as a reprint from the Grove<br />

Press, which already offers Hodeir's<br />

valuable and annoying book. It is<br />

encouraging to find a line of paper<br />

backs hospitable to books on jazz,<br />

but sad to acknowledge that so few<br />

merit reprinting.<br />

—Glenn Coulter<br />

J A M SESSION, edited by Ralph J.<br />

Gleason, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1958<br />

Under the accurately loose-sounding<br />

title, Jam Session and subtitle<br />

"An Anthology of <strong>Jazz</strong>," jazz writer,<br />

reviewer, critic and fas I'm sure he'd<br />

insist on including) still-enthusiastic<br />

veteran jazz fan Ralth Gleason has<br />

compiled an extremely varied thirtysix<br />

piece collection concerned with as¬<br />

pects or people of jazz. All but one<br />

are non-fiction—the exception is<br />

Elliott Grennard's highly effective<br />

"Sparrow's Last Jump," which deals<br />

with a musician who flips, quite literals,<br />

at a recording session, a story<br />

that has been described as an almostnon-fictional<br />

account of a Charlie<br />

Parker session. Like almost any<br />

other anthology in the world, this<br />

volume is clearly designed to be read<br />

in fairly small chunks, or left on the<br />

bedside table. Much of it appears to<br />

have been originally written for light<br />

reading—brief personality sketches,<br />

musicians' reminiscences — although<br />

there are several efforts at serious<br />

critical or analytical writing. On this<br />

level—which is a completely respectable,<br />

and in this case quite enjoyable<br />

level—this is generally a very<br />

successful collection.<br />

If the foregoing seems a somewhat<br />

negative way of speaking well of a<br />

book, it is just because I feel there is<br />

some need to keep the reader from<br />

being deceived by the books' own<br />

presentation of itself. For we have<br />

here another instance of the great<br />

war between publishers and writers<br />

(or anthologists), the manifestation<br />

of which is in the jacket blurb claiming<br />

far more that the man who put<br />

the book together thought of doing,<br />

and the main potential victim of<br />

which is the purchaser of the book.<br />

Mr. Gleason, who is literate and nonpretentious,<br />

notes in his introduction<br />

that he could not make this a winnowing<br />

of the best jazz pieces he has<br />

read in the past twenty years, largely<br />

because so much that seemed good at<br />

the time has turned out on re-inspection<br />

to have grown dated or<br />

corny. So all he claims for the hook<br />

is that it is "an interesting collection<br />

of articles about interesting people,<br />

interesting aspects of jazz and ex¬<br />

planations of it." He notes with re¬<br />

gret that there are no articles about<br />

Duke, Louis, or Bird, but points out<br />

that the book couldn't hope to be allinclusive.<br />

When he takes such an ap¬<br />

proach, it would be unfair to fault<br />

him very much for not including the<br />

work of a single current serious jazz<br />

writer (excepting only himself, and<br />

none of Ralph's several pieces here<br />

are intended as 'serious' writing),<br />

and I would even be inclined to let<br />

him get away with limiting a selection<br />

entitled "<strong>The</strong> Coming of Modern<br />

<strong>Jazz</strong>" to only three selections (one<br />

of which is from <strong>The</strong> Partisan <strong>Review</strong>—and<br />

reads that way; and another<br />

by the splenetically argumentative<br />

and inadequatelv informed<br />

Henry Pleasants). But why, oh why,<br />

does the jacket blurb have to insist<br />

that within these pages is ". . . the<br />

finest writing on jazz that has appeared<br />

during the past two decades<br />

... in pieces by and about the jazz<br />

world's greatest critics, performers<br />

and writers"? Why are we informed<br />

that this anthology seeks "to bring<br />

into perspective the whole body of<br />

... a new and serious writing" about<br />

jazz? It's not really Cleason's fault,<br />

but too much caveat emptor is too<br />

much.<br />

This gripe aside, the book has lots<br />

of good fun in it, as previously indicated.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are some examples of<br />

the rich, ripe Boston prose of George<br />

Erazier; there is that Grennard story<br />

(which I had never read before and<br />

was grateful for) ; there is an old<br />

and interesting Bruce Lippincott<br />

piece that is sort of a theoretical dissection<br />

of the jam session; there are<br />

excerpts from the spoken recordings<br />

of Jelly Roll Morton and Bunk Johnson;<br />

two good items by the late Otis<br />

Ferguson (one of the under-appreciated<br />

early jazz writers); an intriguing<br />

fragment about prohibition<br />

Chicago by Art Hodes, who was<br />

there; Lillian Ross' classic (if you<br />

know how seriously not to take it)<br />

New Yorker yarn on the first clambake<br />

at Newport. <strong>The</strong>re are also lesser<br />

items by less able or interesting<br />

people; and there is a mite too much<br />

of the editor himself (eight selections,<br />

some quite good, but about<br />

three that don't seem worth it: one<br />

on the up-coming of "Rhythm and<br />

Blues" that is rather dated; a 1946<br />

piece on the career of Nat "King"<br />

Cole; and a 1956 detailing of how<br />

active things were in jazz on the<br />

West Coast).<br />

All in all, a good though certainly<br />

not indispensable book, and at its<br />

fully comparable price ($4.95,) a<br />

hetter buy than a lot of twelve-inch<br />

LPs that are issued nowadays. But<br />

if you take this book home, don't forget<br />

to throw away the wrapper before<br />

anyone can get at it.<br />

—Orrln Keepnews<br />

T H E HANDBOOK OF JAZZ, bv Barry<br />

Ulanov. Viking Press, 1957<br />

Somewhere in the vast United<br />

States, it seems there is an institution<br />

called Barnard College, and in this<br />

college there dwells an assistant professor<br />

of the English language called<br />

Barry Ulanov. I state these facts as<br />

categorically as possible because people<br />

who read Ulanov's Handbook will<br />

think there has been some mistake.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Handbook is a pedestrian<br />

hotchpotch of old-hat anecdote and<br />

smug presumption badly written. <strong>The</strong><br />

professor says "flatted" when he<br />

means "flattened" and still believes<br />

after all those years at college that<br />

the flute is a reed instrument. He is<br />

also a past master of the construction<br />

of those wooly sentences which, like<br />

the lights of 'Broadway, look pretty<br />

so long as you don't attempt to read<br />

them.<br />

Early in the book, the professor<br />

tells us that Lester Young's style is<br />

"close-noted." whatever that is supposed<br />

to mean. And then we learn,<br />

later on, that Lester's style features<br />

the use of "sustained open notes"—a<br />

trulv professional example of nonsense<br />

contradicting itself. After this<br />

kind of stuff, the reader is hardly