District Institutes of Education and Training - Teacher Education

District Institutes of Education and Training - Teacher Education

District Institutes of Education and Training - Teacher Education

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DFID’s headquarters are located at:<br />

DFID<br />

1 Palace Street<br />

London SW1E 5HE<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7023 0000<br />

Fax: +44 (0) 20 7023 0019<br />

Website: www.dfid.gov.uk<br />

email: enquiry@dfid.gov.uk<br />

Public enquiry point: 0845 3004100<br />

From overseas: +44 1355 84 3132<br />

08/04 2K Produced for DFID by Fuller-Davies Limited<br />

ISBN 1 86192 606 5<br />

Printed on recycled paper containing a minimum <strong>of</strong> 75% post-consumer waste.<br />

DFID<br />

Abercrombie House<br />

Eaglesham Road<br />

East Kilbride<br />

Glasgow G75 8EA<br />

United Kingdom<br />

55<br />

Researching the Issues<br />

DISTRICT INSTITUTES OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN THREE INDIAN STATES<br />

Researching the Issues<br />

2004<br />

55<br />

DISTRICT INSTITUTES OF<br />

EDUCATION AND TRAINING:<br />

A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN<br />

THREE INDIAN STATES<br />

by Caroline Dyer with Archana Choksi<br />

<strong>and</strong> Vinita Awasty, Uma Iyer, Renu Moyade, Neerja Nigam,<br />

Neetu Purohit, Swati Shah <strong>and</strong> Swati Sheth

DISTRICT INSTITUTES OF<br />

EDUCATION AND TRAINING:<br />

A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN<br />

THREE INDIAN STATES<br />

by Caroline Dyer with Archana Choksi<br />

<strong>and</strong> Vinita Awasty, Uma Iyer, Renu Moyade, Neerja Nigam, Neetu Purohit,<br />

Swati Shah <strong>and</strong> Swati Sheth<br />

2004

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

Department for International Development: <strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

This is one <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Papers issued by the Policy Division <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Department For International Development. Each paper represents a study or<br />

piece <strong>of</strong> commissioned research on some aspects <strong>of</strong> education <strong>and</strong> training in<br />

developing countries. Most <strong>of</strong> the studies were undertaken in order to provide<br />

informed judgements from which policy decisions could be drawn, but in each<br />

case it has become apparent that the material produced would be <strong>of</strong> interest to a<br />

wider audience, particularly those whose work focuses on developing countries.<br />

Each paper is numbered serially, <strong>and</strong> further copies can be obtained through DFID<br />

<strong>Education</strong> Publication Despatch, PO Box 190, Sevenoaks, TN14 5EL, UK –<br />

subject to availability. A full list appears overleaf.<br />

Although these papers are issued by DFID, the views expressed in them are<br />

entirely those <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>and</strong> do not necessarily represent DFID’s own policies<br />

or views. Any discussion <strong>of</strong> their content should therefore be addressed to the<br />

authors <strong>and</strong> not to DFID.<br />

Address for Correspondence<br />

POLIS/Centre for Development Studies<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Leeds<br />

Leeds<br />

LS2 9JT<br />

UK<br />

T +44 113 233 4393<br />

E c.dyer@leeds.ac.uk<br />

F +44 113 343 4400<br />

W www.leeds.ac.uk<br />

© Caroline Dyer<br />

2004<br />

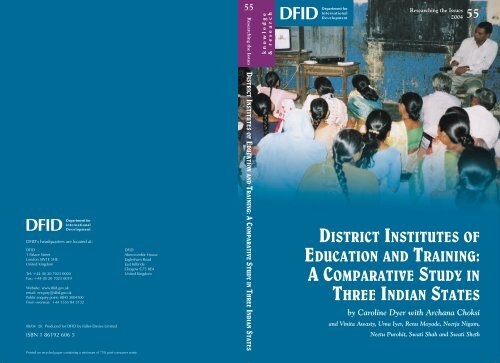

Front Cover Photograph: Archana Choksi<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

No.1 SCHOOL EFFECTIVENESS<br />

IN DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES: A SUMMARY<br />

OF THE RESEARCH<br />

EVIDENCE.<br />

D Pennycuick (1993)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 061 9<br />

No. 2 EDUCATIONAL COST-<br />

BENEFIT ANALYSIS.<br />

J Hough (1993)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 062 7<br />

No.3 REDUCING THE COST<br />

OF TECHNICAL AND<br />

VOCATIONAL<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

L Gray, M Fletcher, P Foster, M<br />

King, A M Warrender (1993)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 063 5<br />

No. 4 REPORT ON READING IN<br />

ENGLISH IN PRIMARY<br />

SCHOOLS IN MALAWI.<br />

E Williams (1993) Out <strong>of</strong> Print<br />

– Available on CD-Rom <strong>and</strong><br />

DFID website<br />

No. 5 REPORT ON READING IN<br />

ENGLISH IN PRIMARY<br />

SCHOOLS IN ZAMBIA.<br />

E Williams (1993) Out <strong>of</strong> Print<br />

– Available on CD-Rom <strong>and</strong><br />

DFID website<br />

See also No. 24, which updates<br />

<strong>and</strong> synthesises No.s 4 <strong>and</strong> 5.<br />

No. 6 EDUCATION AND<br />

DEVELOPMENT: THE<br />

ISSUES AND THE<br />

EVIDENCE.<br />

K Lewin (1993)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 066 X<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No. 7 PLANNING AND<br />

FINANCING<br />

SUSTAINABLE<br />

EDUCATION SYSTEMS IN<br />

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA.<br />

P Penrose (1993)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 067 8<br />

No. 8 Not allocated<br />

No. 9 FACTORS AFFECTING<br />

FEMALE PARTICIPATION<br />

IN EDUCATION IN<br />

SEVEN DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES.<br />

C Brock, N Cammish (1991)<br />

(revised 1997).<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 065 2<br />

No.10 USING LITERACY: A NEW<br />

APPROACH TO POST-<br />

LITERACY METHODS.<br />

A Rogers (1994) Out <strong>of</strong> Print<br />

– Available on CD-ROM <strong>and</strong><br />

DFID website. Updated <strong>and</strong><br />

reissued as No 29.<br />

No.11 EDUCATION AND<br />

TRAINING FOR THE<br />

INFORMAL SECTOR.<br />

K King, S McGrath, F Leach,<br />

R Carr-Hill (1995)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 090 3<br />

No.12 MULTI-GRADE<br />

TEACHING: A REVIEW<br />

OF RESEARCH AND<br />

PRACTICE.<br />

A Little (1995)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 058 9<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No.13 DISTANCE EDUCATION<br />

IN ENGINEERING FOR<br />

DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES.<br />

T Bilham, R Gilmour (1995)<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> Print – Available on CD-<br />

ROM <strong>and</strong> DFID website.<br />

No.14 HEALTH & HIV/AIDS<br />

EDUCATION IN PRIMARY<br />

& SECONDARY SCHOOLS<br />

IN AFRICA & ASIA.<br />

E Barnett, K de Koning,<br />

V Francis (1995)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 069 4<br />

No.15 LABOUR MARKET<br />

SIGNALS & INDICATORS.<br />

L Gray, AM Warrender,<br />

P Davies, G Hurley, C Manton<br />

(1996) Out <strong>of</strong> Print – Available<br />

on CD-ROM <strong>and</strong> DFID<br />

website.<br />

No.16 IN-SERVICE SUPPORT<br />

FOR A TECHNOLOGICAL<br />

APPROACH TO SCIENCE<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

F Lubben, R Campbell,<br />

B Dlamini (1995)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 071 6<br />

No.17 ACTION RESEARCH<br />

REPORT ON “REFLECT”<br />

D Archer, S Cottingham (1996)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 072 4<br />

No.18 THE EDUCATION AND<br />

TRAINING OF ARTISANS<br />

FOR THE INFORMAL<br />

SECTOR IN TANZANIA.<br />

D Kent, P Mushi (1995)<br />

ISBN: 0 90250 074 0<br />

DFID<br />

No.19 GENDER, EDUCATION<br />

AND DEVELOPMENT –<br />

A PARTIALLY<br />

ANNOTATED AND<br />

SELECTIVE<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY.<br />

C Brock, N Cammish (1997)<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> Print – Available on CD-<br />

ROM <strong>and</strong> DFID website.<br />

No.20 CONTEXTUALISING<br />

TEACHING AND<br />

LEARNING IN RURAL<br />

PRIMARY SCHOOLS:<br />

USING AGRICULTURAL<br />

EXPERIENCE.<br />

P Taylor, A Mulhall (Vols 1 & 2)<br />

(1997)<br />

Vol 1 ISBN: 1 861920 45 8<br />

Vol 2 ISBN: 1 86192 050 4<br />

No.21 GENDER AND SCHOOL<br />

ACHIEVEMENT IN THE<br />

CARIBBEAN.<br />

P Kutnick, V Jules, A Layne<br />

(1997) ISBN: 1 86192 080 6<br />

No.22 SCHOOL-BASED<br />

UNDERSTANDING OF<br />

HUMAN RIGHTS IN<br />

FOUR COUNTRIES:<br />

A COMMONWEALTH<br />

STUDY.<br />

R Bourne, J Gundara, A Dev,<br />

N Ratsoma, M Ruk<strong>and</strong>a,<br />

A Smith, U Birthistle (1997)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 095 4<br />

No.23 GIRLS AND BASIC<br />

EDUCATION:<br />

A CULTURAL<br />

ENQUIRY.<br />

D Stephens (1998)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 036 9

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

No.24 INVESTIGATING<br />

BILINGUAL LITERACY:<br />

EVIDENCE FROM<br />

MALAWI AND ZAMBIA.<br />

E Williams (1998)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 041 5No.25<br />

No.25 PROMOTING GIRLS’<br />

EDUCATION IN AFRICA.<br />

N Swainson, S Bendera,<br />

R Gordon, E Kadzamira (1998)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 046 6<br />

No.26 GETTING BOOKS TO<br />

SCHOOL PUPILS IN<br />

AFRICA.<br />

D Rosenberg, W Amaral,<br />

C Odini, T Radebe,<br />

A Sidibé (1998)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 051 2<br />

No.27 COST SHARING IN<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

P Penrose (1998)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 056 3<br />

No.28 VOCATIONAL<br />

EDUCATION AND<br />

TRAINING IN<br />

TANZANIA AND<br />

ZIMBABWE IN THE<br />

CONTEXT OF ECONOMIC<br />

REFORM.<br />

P Bennell (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 061 X<br />

No.29 RE-DEFINING POST-<br />

LITERACY IN A<br />

CHANGING WORLD.<br />

A Rogers, B Maddox, J Millican,<br />

K Newell Jones, U Papen,<br />

A Robinson-Pant (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 069 5<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No.30 IN SERVICE FOR<br />

TEACHER<br />

DEVELOPMENT IN SUB-<br />

SAHARAN AFRICA.<br />

M Monk (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 074 1<br />

No.31 LOCALLY GENERATED<br />

PRINTED MATERIALS IN<br />

AGRICULTURE:<br />

EXPERIENCE FROM<br />

UGANDA & GHANA<br />

I Carter (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 079 2<br />

No.32 SECTOR WIDE<br />

APPROACHES TO<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

M Ratcliffe, M Macrae (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 131 4<br />

No.33 DISTANCE EDUCATION<br />

PRACTICE: TRAINING &<br />

REWARDING AUTHORS.<br />

H Perraton, C Creed (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 136 5<br />

No.34 THE EFFECTIVENESS OF<br />

TEACHER RESOURCE<br />

CENTRE STRATEGY.<br />

Ed. G Knamiller, (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 141 1<br />

No.35 EVALUATING IMPACT<br />

Ed. V McKay, C Treffgarne<br />

(1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 191 8<br />

No.36 AFRICAN JOURNALS<br />

A Alemna, V Chifwepa,<br />

D Rosenberg (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 157 8<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No.37 MONITORING THE<br />

PERFORMANCE OF<br />

EDUCATIONAL<br />

PROGRAMMES IN<br />

DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES.<br />

R Carr-Hill, M Hopkins,<br />

A Riddell, J Lintott (1999)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 224 8No.38<br />

No.38 TOWARDS RESPONSIVE<br />

SCHOOLS – SUPPORTING<br />

BETTER SCHOOLING<br />

FOR DISADVANTAGED<br />

CHILDREN<br />

(case studies from Save the<br />

Children). M Molteno,<br />

K Ogadhoh, E Cain,<br />

B Crumpton (2000)<br />

No.39 PRELIMINARY<br />

INVESTIGATION OF THE<br />

ABUSE OF GIRLS IN<br />

ZIMBABWEAN JUNIOR<br />

SECONDARY SCHOOLS.<br />

F Leach, P Machankanja with<br />

J M<strong>and</strong>oga (2000)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 279 5<br />

No.40 THE IMPACT OF<br />

TRAINING ON WOMEN’S<br />

MICRO-ENTERPRISE<br />

DEVELOPMENT<br />

F Leach, S Abdulla,<br />

H Appleton, J el-Bushra,<br />

N Cardenas, K Kebede,<br />

V Lewis, S Sitaram (2000)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 284 1<br />

DFID<br />

No.41 THE QUALITY OF<br />

LEARNING AND<br />

TEACHING IN<br />

DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES: ASSESSING<br />

LITERACY AND<br />

NUMERACY IN MALAWI<br />

AND SRI LANKA.<br />

D Johnson, J Hayter,<br />

P Broadfoot (2000)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 313 9<br />

No.42 LEARNING TO<br />

COMPETE: EDUCATION,<br />

TRAINING &<br />

ENTERPRISE IN GHANA,<br />

KENYA & SOUTH AFRICA.<br />

D Afenyadu, K King,<br />

S McGrath, H Oketch,<br />

C Rogerson, K Visser (2001)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 314 7<br />

No.43 COMPUTERS IN<br />

SECONDARY SCHOOLS<br />

IN DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES: COSTS AND<br />

OTHER ISSUES.<br />

A Cawthera (2001)<br />

ISBN 1 86192 418 6<br />

No.44 THE IMPACT OF HIV/<br />

AIDS ON THE<br />

UNIVERSITY OF<br />

BOTSWANA: DEVELOPING<br />

A COMPREHENSIVE<br />

STRATEGIC RESPONSE.<br />

B Chilisa, P Bennell, K Hyde<br />

(2001)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 467 4

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

No.45 THE IMPACT OF HIV/<br />

AIDS ON PRIMARY AND<br />

SECONDARY EDUCATION<br />

IN BOTSWANA:<br />

DEVELOPING A<br />

COMPREHENSIVE<br />

STRATEGIC RESPONSE.<br />

P Bennell, B Chilisa, K Hyde,<br />

A Makgothi, E Molobe,<br />

L Mpotokwane (2001)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 468 2<br />

No.46 EDUCATION FOR ALL:<br />

POLICY AND PLANNING<br />

– LESSONS FROM SRI<br />

LANKA.<br />

A Little (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 552 0<br />

No.47 REACHING THE POOR –<br />

THE 'COSTS' OF SENDING<br />

CHILDREN TO SCHOOL.<br />

S Boyle, A Brock, J Mace,<br />

M Sibbons (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 361 9<br />

No.48 CHILD LABOUR AND ITS<br />

IMPACT ON CHILDREN’S<br />

ACCESS TO AND<br />

PARTICIPATION IN<br />

PRIMARY EDUCATION –<br />

A CASE STUDY FROM<br />

TANZANIA.<br />

H.A Dachi <strong>and</strong> R.M Garrett<br />

(2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 536 0<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No.49a MULTI - SITE TEACHER<br />

EDUCATION RESEARCH<br />

PROJECT (MUSTER)<br />

RESEARCHING TEACHER<br />

EDUCATION – NEW<br />

PERSPECTIVES ON<br />

PRACTICE,<br />

PERFORMANCE AND<br />

POLICY (Synthesis Report).<br />

K. M. Lewin <strong>and</strong> J. S. Stuart<br />

(2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 545 X<br />

No.49b TEACHER TRAINING IN<br />

GHANA – DOES IT<br />

COUNT?<br />

K. Akyeampong (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 546 8<br />

No.49c INITIAL PRIMARY<br />

TEACHER EDUCATION<br />

IN LESOTHO.<br />

K.Pulane Lefoka with E.Molapi<br />

Sebatane (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 547 64<br />

No.49d PRIMARY TEACHER<br />

EDUCATION IN MALAWI:<br />

INSIGHTS INTO<br />

PRACTICE AND POLICY.<br />

D. Kunje with K. Lewin <strong>and</strong><br />

J. Stuart (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 548 4<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Papers<br />

No.49e AN ANALYSIS OF<br />

PRIMARY TEACHER<br />

EDUCATION IN<br />

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO.<br />

J. George, L. Quamina-Alyejina<br />

(2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 549 2<br />

No.50 USING ICT TO INCREASE<br />

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF<br />

COMMUNITY-BASED,<br />

NON-FORMAL<br />

EDUCATION FOR RURAL<br />

PEOPLE IN SUB-<br />

SAHARAN AFRICA<br />

The CERP project (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 568 9<br />

No.51 GLOBALISATION AND<br />

SKILLS FOR<br />

DEVELOPMENT IN<br />

RWANDA AND TANZANIA<br />

L. Tikly, J. Lowe, M. Crossley,<br />

H. Dachi, R. Garrett <strong>and</strong><br />

B.Mukabaranga (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 569 7<br />

No.52 UNDERSTANDINGS OF<br />

EDUCATION IN AN<br />

AFRICAN VILLAGE:<br />

THE IMPACT OF<br />

INFORMATION AND<br />

COMMUNICATION<br />

TECHNOLOGIES<br />

J. Pryor <strong>and</strong> J.G Ampiah (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 570 0<br />

NOW AVAILABLE – CD-ROM<br />

containing full texts <strong>of</strong> Papers<br />

1-42<br />

Other DFID <strong>Education</strong>al Studies<br />

Also Available:<br />

REDRESSING GENDER<br />

INEQUALITIES IN EDUCATION.<br />

N Swainson (1995)<br />

FACTORS AFFECTING GIRLS’<br />

ACCESS TO SCHOOLING IN<br />

NIGER. S Wynd (1995)<br />

EDUCATION FOR<br />

RECONSTRUCTION.<br />

D Phillips, N Arnhold, J Bekker,<br />

N Kersh, E McLeish (1996)<br />

AFRICAN JOURNAL<br />

DISTRIBUTION PROGRAMME:<br />

EVALUATION OF 1994 PILOT<br />

PROJECT. D Rosenberg (1996)<br />

TEACHER JOB SATISFACTION<br />

IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.<br />

R Garrett (1999)<br />

A MODEL OF BEST PRACTICE<br />

AT LORETO DAY SCHOOL,<br />

SEALDAH, CALCUTTA.<br />

T Jessop (1998)<br />

LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES<br />

FOR ALL.<br />

DFID Policy Paper (1999)<br />

THE CHALLENGE OF<br />

UNIVERSAL PRIMARY<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

DFID Target Strategy Paper (2001)<br />

CHILDREN OUT OF SCHOOL.<br />

DFID Issues Paper (2001)<br />

All publications are available free <strong>of</strong> charge from DFID <strong>Education</strong> Publications<br />

Despatch, PO Box 190, Sevenoaks, TN14 5EL, or by email from<br />

dfidpubs@eclogistics.co.uk<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We are grateful to all those colleagues in DIETs, teachers <strong>and</strong> student teachers who<br />

engaged with this project <strong>and</strong> gave the research team the opportunities to work<br />

with them <strong>and</strong> discuss their practices. We are also indebted to the Directors <strong>and</strong><br />

staff <strong>of</strong> GCERT, Gujarat, SIERT in Rajasthan, <strong>and</strong> SCERT in Madhya Pradesh; to<br />

staff at the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Human Resource Development in the Government <strong>of</strong><br />

India; <strong>and</strong> to DPEP personnel for their support to this project.<br />

Without the financial support <strong>of</strong> the UK’s Department for International<br />

Development this project could not have been undertaken. We are grateful for this,<br />

<strong>and</strong> also to several individuals within DFID for their support for, <strong>and</strong> interest in,<br />

this project.<br />

At the University <strong>of</strong> Manchester, the support <strong>and</strong> advice <strong>of</strong> colleagues has been<br />

much appreciated. We also thank our families <strong>and</strong> friends for hearing our stories<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>fering support <strong>and</strong> encouragement along the way.<br />

i DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Acknowledgments i<br />

Contents ii<br />

Abbreviations vi<br />

Executive Summary vii<br />

0.1 Introduction 1<br />

0.2 Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan<br />

0.3 Project intentions <strong>and</strong><br />

1<br />

methodology 2<br />

0.4 Site selection 5<br />

0.5 Research team 6<br />

0.6 About this report 7<br />

Chapter 1<br />

Towards Quality<br />

Improvements for<br />

<strong>Teacher</strong> <strong>Education</strong>:<br />

Decentralising<br />

the System<br />

1.1 Introduction 11<br />

1.2 The pr<strong>of</strong>essional development <strong>of</strong><br />

teachers 11<br />

1.3 The organisation <strong>of</strong> teacher<br />

education 12<br />

1.4 Reporting relationships 15<br />

1.5 Quality <strong>of</strong> the <strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong> 17<br />

1.6 Summary 18<br />

1.7 Policy issue 19<br />

Chapter 2<br />

<strong>Teacher</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Teaching<br />

2.1 Introduction 21<br />

2.2 School observations 22<br />

2.3 <strong>Teacher</strong>s’ attitudes 41<br />

Contents<br />

2.4 Summary 45<br />

2.5 Policy issues 46<br />

Chapter 3<br />

Infrastructure, Staffing,<br />

Institutional Aims <strong>and</strong><br />

Leadership<br />

3.1 Introduction 49<br />

3.2 Relationships between DIETs<br />

<strong>and</strong> external intervention<br />

programmes 50<br />

3.3 Physical infrastructure in the<br />

project DIETs 53<br />

3.4 Staffing 55<br />

3.5 Activities <strong>of</strong> the DIET 60<br />

3.6 Leadership in the DIET 65<br />

3.7 DIET staff ’s perceptions <strong>of</strong><br />

constraints to effective<br />

functioning 68<br />

3.8 Policy implications 69<br />

Chapter 4<br />

Pre-Service <strong>Education</strong><br />

4.1 Introduction 73<br />

4.1 Student teacher intake 73<br />

4.2 The pre-service course 74<br />

4.3 Summary 90<br />

4.4 Policy implications 91<br />

Chapter 5<br />

In-service <strong>Education</strong> for<br />

<strong>Teacher</strong>s<br />

5.1 Introduction<br />

5.2 In-service training<br />

93<br />

programmes 93<br />

5.3 The logistics <strong>of</strong> training<br />

programmes 100<br />

DFID ii

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Contents - Continued<br />

5.4 <strong>Training</strong> processes 101<br />

5.5 <strong>Teacher</strong> motivation 109<br />

5.6 The model <strong>of</strong> in-service teacher<br />

education 110<br />

5.7 Policy implications 111<br />

Chapter 6<br />

The Diet <strong>and</strong> Decentralisation<br />

6.1 Introduction 113<br />

6.2 The DIET <strong>and</strong> the State 113<br />

6.3 The DIET in the <strong>District</strong><br />

6.4 DIETs <strong>and</strong> the Resource<br />

117<br />

Centres 124<br />

6.5 Policy implications 128<br />

Chapter 7<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development<br />

through Collaborative Action<br />

Research with DIETs<br />

7.1 Introduction 131<br />

7.2 Pr<strong>of</strong>essional development for<br />

DIET staff 131<br />

7.3 The Action-Reflection cycle<br />

with DIETs 134<br />

7.4 Processes <strong>and</strong> findings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

action research projects 138<br />

7.5 Pr<strong>of</strong>essional development<br />

issues 147<br />

7.6 Role <strong>of</strong> the process helpers 150<br />

7.7 Tensions for action-reflection 151<br />

7.8 Policy implications 153<br />

Chapter 8<br />

Action Research with <strong>Teacher</strong>s<br />

8.1 Introduction 155<br />

8.2 Learning to reflect 155<br />

8.3 Constraints to teaching 159<br />

8.4 Approaches to teaching <strong>and</strong><br />

learning literacy 163<br />

8.5 Limitations <strong>of</strong> current<br />

approaches 166<br />

8.6 From reflection to input 167<br />

8.7 Project termination 167<br />

8.8 Policy implications 168<br />

Chapter 9<br />

Research into Action:<br />

The New Textbook <strong>Training</strong><br />

Programmes in Gujarat<br />

9.1 Introduction<br />

9.2 The new textbooks <strong>and</strong> the<br />

171<br />

training programme 171<br />

9.3 Cascade training 172<br />

9.4 From Palitana to the <strong>District</strong>s 176<br />

9.5 Year Two textbook training 180<br />

9.6 Improving cascade<br />

effectiveness 184<br />

9.7 Sustaining inputs from cascade<br />

training: the role <strong>of</strong> Cluster<br />

Resource Centres 185<br />

9.8 Development <strong>of</strong> trainers 186<br />

9.8 <strong>Teacher</strong> motivation 188<br />

9.9 Policy implications 188<br />

Chapter 10<br />

Summary <strong>of</strong> Main Findings<br />

<strong>and</strong> Policy Implications<br />

10.1 Introduction 191<br />

10.2 Summary <strong>of</strong> main findings 191<br />

10.3 Ways forward 202<br />

References 213<br />

Annexes 217<br />

iii DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Annex 1<br />

Expansion <strong>and</strong> new directions<br />

in elementary education 217<br />

Annex 2<br />

Reform <strong>of</strong> pre-service training<br />

in Gujarat 221<br />

Annex 3<br />

Institutional reform in<br />

Madhya Pradesh 231<br />

Boxes<br />

0.1 The <strong>District</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong><br />

Programme 7<br />

0.2 Lok Jumbish 9<br />

1.1 Cluster <strong>and</strong> Block Resource<br />

Centres 15<br />

1.2 Madhya Pradesh State critique <strong>of</strong><br />

teacher education 17<br />

1.3 Rajasthan State critique <strong>of</strong><br />

teacher education 18<br />

2.1 Curriculum innovation: the<br />

competency-based approach<br />

<strong>of</strong> Minimum Levels <strong>of</strong><br />

Learning 21<br />

2.2 A code <strong>of</strong> conduct for teachers<br />

in Gujarat’s new Std. 1<br />

textbook 25<br />

2.3 The school day in Gaamru 23<br />

3.1 If a teacher educator doesn’t<br />

have the skills... 59<br />

4.1 The PRESET course <strong>and</strong> marks<br />

in Rajasthan (up to 2001) 75<br />

4.2 Hindi language teaching, first<br />

year, Indore DIET 3.3.00 77<br />

4.3 English language teaching, first<br />

year, Indore DIET,<br />

26.2.2000 79<br />

4.4 Learning to be a teacher: practice<br />

lesson by a second year trainee to<br />

year 6 students, Santramapur<br />

5.9.00 81<br />

Contents - Continued<br />

5.1 Planning for MLL training,<br />

Masuda DIET, April 1999 96<br />

5.2 10 desirable points for a Master<br />

Trainer, Masuda DIET 99<br />

5.3 Lok Jumbish training, third day<br />

6.7.99 Summary <strong>of</strong> maths<br />

session 107<br />

6.1 Capacity development <strong>of</strong> BRC<br />

<strong>and</strong> CRCs, Santrampur 1998 127<br />

7.1 Action research in crosscultural<br />

transition 134<br />

7.2 Underst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>of</strong> research in<br />

Indore DIET 135<br />

7.3 Dhar teachers’ expectations <strong>of</strong><br />

the DIET 143<br />

7.4 Prompts for transmission<br />

loss diary 145<br />

9.1 Good practices in training with<br />

video 178<br />

9.2 Good practices by MTs in<br />

Surat 183<br />

9.3 Trainer evaluation: some<br />

preliminary steps 187<br />

Tables<br />

1.1 Suggested branches <strong>and</strong> staffing<br />

<strong>of</strong> a DIET 14<br />

2.1 Gaamru school enrolment<br />

2000 23<br />

3.1 Socio-educational pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the<br />

six project <strong>District</strong>s 49<br />

3.2 Organisation <strong>of</strong> the Lok Jumbish<br />

DIETs 51<br />

3.3 Staffing across sample 1999-<br />

2000 56<br />

3.4 Qualifications <strong>and</strong> previous<br />

employment <strong>of</strong> staff in Dhar<br />

DIET in Madhya Pradesh 58<br />

DFID iv

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Contents - Continued<br />

7.2 Reflection on teacher<br />

responses 150<br />

8.1 Students enrolled, present, <strong>and</strong><br />

average working days in March<br />

2000 160<br />

8.2 Children’s literacy progress by<br />

March 2001 165<br />

9.1 Effective <strong>and</strong> ineffective training<br />

practices 180<br />

Figures<br />

0.1 Situation analysis framework 5<br />

0.2 Site locations 8<br />

1.1 Relationships between the DIET,<br />

DPEP <strong>and</strong> Cluster Resource<br />

Centres 16<br />

1.2 Children studying in Gaamru<br />

school 31<br />

1.3 Year One boy writing on<br />

blackboard, Gaamru school 31<br />

4.1 Practice teaching, Indore DIET<br />

84<br />

4.2 Revised practice teaching<br />

evaluation plan, Santrampur<br />

DIET 87<br />

5.1 The lecturing approach to<br />

INSET 104<br />

5.2 Generating teacher discourse<br />

<strong>and</strong> participation 109<br />

6.1 CRC concerns, Santrampur<br />

<strong>District</strong> 126<br />

7.1 Discussing questionnaire design<br />

139<br />

7.2 A cascade training model,<br />

Madhya Pradesh 144<br />

8.1 Action researchers discussing<br />

practices 158<br />

9.1 The cascade tiers, Std. 1<br />

training 173<br />

9.2 New textbook training at the<br />

Master Trainer level <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cascade 175<br />

9.3 <strong>Training</strong> by video 179<br />

9.4 Enriching the cascade by<br />

consolidation by Cluster<br />

Resource Centres 186<br />

10.1 Matching people to posts:<br />

an application <strong>of</strong> the<br />

competency wheel 204<br />

10.2 A model for training<br />

consolidation at Cluster<br />

Resource level 206<br />

10.3 A centralised model <strong>of</strong><br />

management 209<br />

10.4 A ‘responsive’ model <strong>of</strong><br />

management 209<br />

10.5 DIET support for Whole<br />

School improvement 210<br />

v DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

ADEI/SDI School inspector<br />

AS Alternative Schooling<br />

BTI Basic <strong>Training</strong> Institute<br />

BRC Block Resource Centre<br />

CMDE Curriculum <strong>and</strong> Materials<br />

Development<br />

CRC Cluster Resource Centre<br />

DIET <strong>District</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong><br />

DPEP <strong>District</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong><br />

Programme<br />

DRU <strong>District</strong> Resource Unit<br />

EGS <strong>Education</strong> Guarantee Scheme<br />

ET <strong>Education</strong>al Technology<br />

GCERT Gujarat Council <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Research <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Training</strong><br />

GPSC Gujarat Public Services<br />

Commission<br />

GNP Gross National Product<br />

HSC Higher Secondary Certificate<br />

IASE Institute for Advanced Study<br />

in <strong>Education</strong><br />

IFIC In-service Programmes, Field<br />

Interaction <strong>and</strong> Innovation<br />

Co-ordination<br />

INSET In-service <strong>Teacher</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

LJ Lok Jumbish<br />

MEd Master <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

MHRD Ministry <strong>of</strong> Human Resource<br />

Development<br />

MLL Minimum Level <strong>of</strong> Learning<br />

MP Madhya Pradesh<br />

NCERT National Council <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Research <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Training</strong><br />

Abbreviations<br />

NCTE National Council for <strong>Teacher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong><br />

NGO Non-Government<br />

Organisation<br />

NIEPA National Institute for<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Planning <strong>and</strong><br />

Administration<br />

NPE National Policy on <strong>Education</strong><br />

OIC Officer in Charge<br />

PAC Programme Advisory<br />

Committee<br />

P & M Planning <strong>and</strong> Management<br />

PhD Doctor <strong>of</strong> Philosophy<br />

PSTE Pre-service <strong>Teacher</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong><br />

PTC Primary <strong>Teacher</strong> Certificate<br />

Pre-set Pre-service teacher education<br />

OB Operation Blackboard<br />

SCERT State Council <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>al<br />

Research <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong><br />

(Madhya Pradesh)<br />

SIDA Swedish International<br />

Development Agency<br />

SIERT State Institute for<br />

<strong>Education</strong>al Research <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Training</strong> (Rajasthan)<br />

SOPT Special Orientation for<br />

Primary <strong>Teacher</strong>s<br />

SSA Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan<br />

SSC Secondary Schooling<br />

Certificate<br />

TLM Teaching Learning Materials<br />

UEE Universal Elementary<br />

<strong>Education</strong><br />

WE Work Experience<br />

DFID vi

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Research for policy <strong>and</strong> practitioner development: key areas <strong>of</strong> this report<br />

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong> (DIETs), founded during the late<br />

1980s <strong>and</strong> early 1990s, are expected to play a key role within India’s current drives<br />

to achieve Universal Elementary <strong>Education</strong> <strong>of</strong> quality. This research project<br />

focused on six DIETs, two each in the states <strong>of</strong> Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh <strong>and</strong><br />

Rajasthan. In each state, one DIET was in a <strong>District</strong> where an external intervention<br />

was running (Lok Jumbish in Rajasthan <strong>and</strong> the <strong>District</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong><br />

Programme in the other two states).<br />

The study adopted an ethnographic approach to data generation. This approach,<br />

by focusing on underst<strong>and</strong>ing realities as perceived by teachers, their educators,<br />

<strong>and</strong> educational <strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>and</strong> making connections between them, leads to<br />

grounded <strong>and</strong> contextualised findings. The report contributes to policy <strong>and</strong><br />

practitioner development in four main areas:<br />

• It provides otherwise absent ethnographic detail about educational processes in<br />

DIETs <strong>and</strong> related schools, identifying links <strong>and</strong> gaps between teacher<br />

development programmes <strong>and</strong> teachers’ pr<strong>of</strong>essional development needs<br />

• It considers how decentralisation has affected DIETs, <strong>and</strong> identifies areas <strong>of</strong><br />

unresolved tensions in relation to power <strong>and</strong> autonomy that constrain effective<br />

functioning<br />

• It engages with the pressing question <strong>of</strong> teachers’ will to adopt change messages<br />

through a critique <strong>of</strong> the relevance <strong>of</strong> the transmission-based training model<br />

that dominates both pre- <strong>and</strong> in-service training<br />

• It explores an alternative approach to practitioner development, based on<br />

collaborative reflection <strong>and</strong> action, that stimulates engagement <strong>and</strong><br />

contextualised actions<br />

Aims <strong>and</strong> objectives <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

The study’s overall aim was:<br />

Through the use <strong>of</strong> participatory methods, to evaluate the functioning <strong>of</strong><br />

selected DIETs within the decentralised framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>District</strong> Planning<br />

initiatives; <strong>and</strong> to initiate where necessary, <strong>and</strong> otherwise support, a process by<br />

which the capacity <strong>of</strong> these institutions to meet their objectives is enhanced<br />

through critical reflection <strong>and</strong> action.<br />

In order to achieve this aim, the objectives <strong>of</strong> the research were:<br />

1 To appraise existing situations in selected elementary schools vis-à-vis physical<br />

conditions, clientele, availability <strong>of</strong> teaching-learning materials, teacher<br />

motivation, classroom management style, pedagogical approaches, administrative<br />

<strong>and</strong> pedagogical support, interaction with village communities, <strong>and</strong> so on.<br />

2 To analyse each DIET’s contribution to the pr<strong>of</strong>essional development <strong>of</strong><br />

teachers by examining:<br />

vii DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

a) the extent to which pre-service education prepares teachers for the<br />

circumstances in which they will find themselves once in post<br />

b) the quality <strong>of</strong> in-service inputs <strong>and</strong> delivery mechanisms, <strong>and</strong> fit between<br />

training programmes <strong>and</strong> teachers’ perceived needs<br />

c) the capacity <strong>of</strong> each DIET to engage in research that relates to their own <strong>and</strong><br />

teachers’ needs.<br />

3 To assess each DIET’s internal managerial capacity <strong>and</strong> its external relationships<br />

with institutions in the <strong>District</strong> <strong>and</strong> other levels <strong>of</strong> the administrative hierarchy,<br />

<strong>and</strong> review how they are integrated into the strategy <strong>of</strong> universalising<br />

elementary education.<br />

4 To use research findings in a continuous process <strong>of</strong> providing support <strong>and</strong><br />

initiative to assist the development <strong>of</strong> capacity in DIETs, <strong>and</strong> to use this research<br />

project to strengthen <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> that capacity through both participation <strong>and</strong><br />

example, both at the <strong>District</strong> <strong>and</strong> other levels <strong>of</strong> the administration where<br />

stakeholders have been identified.<br />

Findings<br />

Trends across the sample sites indicate a need for readjustment <strong>and</strong> focused<br />

development <strong>of</strong> DIETs in a process <strong>of</strong> institutional renewal if they are to be<br />

effective in systemic support for teacher development. The report raises four areas<br />

<strong>of</strong> key concern for policy <strong>and</strong> practitioner communities:<br />

• The need for a sharper conceptualisation <strong>of</strong> institutional purpose <strong>and</strong> the roles<br />

<strong>of</strong> DIET branches <strong>and</strong> DIET staff in relation to that institutional purpose<br />

• The need for a holistic rather than compartmentalised approach to teacher<br />

development through DIETs<br />

• The need to recognise the specialised nature <strong>of</strong> elementary teaching <strong>and</strong> teacher<br />

education <strong>and</strong> recruit DIET staff, as elementary teacher educators, accordingly<br />

• The need to provide for continuous pr<strong>of</strong>essional growth <strong>of</strong> teacher educators to<br />

extend their underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong>, <strong>and</strong> engagement with, the field, for example<br />

through encouraging processes <strong>of</strong> reflection <strong>and</strong> action<br />

A sharper conceptualisation <strong>of</strong> institutional purpose<br />

Processes <strong>of</strong> devolving power <strong>and</strong> autonomy for teacher development to DIETs<br />

remain, despite policy intentions, incomplete. Tensions <strong>of</strong> decentralisation hamper<br />

the DIET in emerging as an institute firmly embedded in, <strong>and</strong> serving, its <strong>District</strong>.<br />

In-service teacher education programmes are designed <strong>and</strong> funded at state level or<br />

above, <strong>and</strong> delivered at the <strong>District</strong> level, according to numerical targets. Although<br />

evaluation <strong>and</strong> follow-up <strong>of</strong> training impact in the field are rarely undertaken,<br />

DIET staff deliver programmes they sense are not meeting teachers’ needs.<br />

Current centralised arrangements fail to challenge their sense that it is their duty<br />

to deliver what they are given, rather than adapt materials to local conditions <strong>and</strong><br />

DFID viii

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

requirements as the DIET m<strong>and</strong>ate envisages. A further barrier to effective<br />

decentralisation lies in DIET staff ’s lack <strong>of</strong> the technical skills needed to assess<br />

teachers’ needs, <strong>and</strong> respond accordingly – which can serve as a justification for not<br />

challenging state-generated programmes. Decentralisation initiatives in Madhya<br />

Pradesh address some <strong>of</strong> these issues, but the need to support DIET staff in<br />

developing appropriate skills to work effectively in a decentralised context remains.<br />

Not all staff members were aware <strong>of</strong> the functions <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the DIET’s branches.<br />

Staff related easily to the ‘traditional’ occupations - pre-service <strong>and</strong> in-service<br />

training - but had less clear underst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>of</strong> the role in elementary education <strong>of</strong>,<br />

for example, planning <strong>and</strong> management or curriculum development. Reflecting<br />

this, teachers saw the DIET as a training institute, rather than as the holistic<br />

teacher development institute policy envisaged.<br />

The apex State level institute in each State, itself undergoing revitalisation under<br />

the same scheme that established DIETs, tended towards an evaluative rather than<br />

supportive role. The majority <strong>of</strong> sample DIETs would benefit from proactive<br />

support in forging a meaningful purpose <strong>and</strong> identity, <strong>and</strong> in resolution <strong>of</strong> the apex<br />

institute’s role vis-à-vis DIETs.<br />

Within their <strong>District</strong>, two <strong>of</strong> the six sample DIETs had created their own niche<br />

through proactively developing a pr<strong>of</strong>ile for the DIET. Through proactive<br />

leadership by its Principal, Surat DIET in Gujarat had become firmly established<br />

as a prime local educational resource. It was a hub <strong>of</strong> educational activity <strong>and</strong> had<br />

undertaken needs analyses, developed programmes with local relevance, <strong>and</strong><br />

effectively mobilised local human <strong>and</strong> financial resources. Indore DIET was also<br />

establishing a similar identity. Both these DIETs also demonstrated not only the<br />

importance <strong>of</strong> partnerships with Cluster Resource Centres for effective outreach,<br />

but also the continuing relevance <strong>of</strong> the DIET idea.<br />

With a network <strong>of</strong> support institutions for decentralised teacher education now in<br />

place, action is needed by each to ensure that they interact effectively with one<br />

another. Decentralisation requires the creation <strong>of</strong> meaningful <strong>of</strong> State-DIET-<br />

Cluster Resource Centre partnerships, where links <strong>and</strong> purposes in relation to<br />

teacher development are clearly defined. Proactive nurturing <strong>of</strong> new identities <strong>and</strong><br />

capacity development is needed to assist in maximising the strategic position <strong>of</strong><br />

each institution, <strong>and</strong> moving away from embedded centralised relations.<br />

Towards holistic teacher development<br />

The model <strong>of</strong> teacher education adopted in both pre- <strong>and</strong> in-service training is a<br />

transmission approach to developing skills <strong>and</strong> knowledge. Development <strong>of</strong> skills<br />

ix DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

follows the format <strong>of</strong> learning to deliver a model lesson; <strong>and</strong> knowledge relates to<br />

learning <strong>and</strong>/or reinforcing subject content. Many DIET staff are reluctant to<br />

model the approaches they lecture about.<br />

Transferability <strong>of</strong> what is learned in training, from both pre- <strong>and</strong> in-service programmes,<br />

to multi-lingual, multi-ethnic, multi-ability <strong>and</strong> multi-grade primary classroom<br />

contexts remains problematic. <strong>Teacher</strong>s report the lack <strong>of</strong> relevance <strong>of</strong> training <strong>and</strong><br />

have <strong>of</strong>ten developed low expectations <strong>of</strong> its being able to make any difference.<br />

Another issue that is hampering quality improvements is the pattern <strong>of</strong> once-<strong>of</strong>f, <strong>of</strong>fsite<br />

training courses for teachers. The current approach to teacher development<br />

through DIETs is focused on the individual teacher, <strong>and</strong> short-term inputs <strong>of</strong> technical<br />

skilling. <strong>Training</strong> <strong>of</strong> this nature is not able to challenge teachers’ <strong>of</strong>ten negative<br />

assumptions about the intelligence <strong>and</strong> capacities <strong>of</strong> children from lower socioeconomic<br />

strata, which create barriers to their will to change their practices. <strong>Training</strong><br />

that comprises skilling <strong>and</strong> content reinforcement is failing to engage teachers with<br />

training ideas, <strong>and</strong> sees elementary teachers as mere ‘classroom technicians’. Further<br />

thought needs to be given to how training can work towards developing teachers’<br />

potential as creative practitioners, <strong>and</strong> validate <strong>and</strong> extend their existing knowledge.<br />

There is a pressing need to improve the ‘ecological validity’ <strong>of</strong> the training <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

to teachers through DIETs, to improve its contextual relevance. The current<br />

model, even if improved significantly in quality, lacks the capacity to be<br />

contextually sensitive <strong>and</strong> thus has shortcomings in relation to the pr<strong>of</strong>essed aims<br />

<strong>of</strong> establishing DIETs as responsive local institutions. However, to enhance the<br />

transferability <strong>of</strong> what is learned during in-service training under current<br />

arrangements, further thought must be given as to how inputs from DIET training<br />

courses articulate with opportunities for peer reflection <strong>of</strong>fered at the Cluster<br />

Resource Centres. Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> DIET training would be enhanced by advance<br />

planning <strong>of</strong> how Cluster Resource Centres can assist in working with teachers on<br />

transferring training messages into practice by experimentation <strong>and</strong> discussion in<br />

a supportive peer group; <strong>and</strong> the DIET’s role in this process.<br />

In the longer term, it is desirable that these structures shift towards providing<br />

support to a strategy <strong>of</strong> whole school, rather than individual teacher, development.<br />

Whole school development <strong>of</strong>fers greater potential to address in a integrated way<br />

current concerns about enhancing community participation, embedding schools<br />

into their socio-economic context, <strong>and</strong> improving internal efficiency.<br />

Recruitment <strong>of</strong> primary teacher educators<br />

Recruitment criteria for DIETs specified that staff should have two Master’s<br />

degrees <strong>and</strong> seven years <strong>of</strong> elementary teaching experience. Few elementary<br />

DFID x

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

teachers have these academic qualifications, but as they have been prioritised over<br />

the practitioner experience criterion, DIETs have largely been staffed by ex-upper<br />

secondary teachers, who hold higher degrees but have no relevant practitioner<br />

experience. Many staff have been posted to DIETs by routine government transfer<br />

procedures, resulting in a widespread lack <strong>of</strong> enthusiasm for their new post. Short<br />

staffing <strong>of</strong> Principals was widely in evidence <strong>and</strong> had a detrimental effect on staff<br />

motivation <strong>and</strong> direction-setting for DIETs. Specific recruitment criteria<br />

developed by Lok Jumbish in Rajasthan brought interested elementary<br />

practitioners to the DIETs Lok Jumbish adopted, but despite <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> this success, personalisation <strong>of</strong> recruitment criteria was seen<br />

to be too risky to be adopted for government recruitment across the State.<br />

Once appointed, DIET staff in all three States judged induction processes to be<br />

inadequate. They left a significant proportion <strong>of</strong> staff unfamiliar with the role <strong>of</strong><br />

the DIET itself, or <strong>of</strong> the branch within they worked.<br />

A posting to the DIET is a clear change <strong>of</strong> career direction, from being a teacher<br />

to a teacher educator. Elementary teacher educators who do not have relevant<br />

practitioner experience lack the pedagogical authority needed to support<br />

elementary teacher development. Current recruitment norms are not designed to<br />

assess the knowledge, skills <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ings required <strong>of</strong> a primary teacher<br />

educator. This study provides evidence <strong>of</strong> the desirability <strong>of</strong> revising those norms;<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> the need to recognise the specialised nature <strong>and</strong> challenges <strong>of</strong> working as an<br />

elementary teacher educator <strong>and</strong> recruit accordingly.<br />

Continuous pr<strong>of</strong>essional development for teacher educators<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essional development opportunities for DIET staff are very limited <strong>and</strong><br />

appropriated by a h<strong>and</strong>ful <strong>of</strong> staff. In addition to the recommended review <strong>of</strong><br />

recruitment procedures, there is a need to develop a policy strategy to address<br />

teacher educators’ ongoing pr<strong>of</strong>essional development needs.<br />

The study trialled collaborative action research as a means <strong>of</strong> developing DIET<br />

staff ’s research capacity <strong>and</strong> supporting systematic investigation <strong>of</strong> field realities.<br />

This reflection-on-action approach departed from the ‘expert’-led, transmission<br />

approach which dominates practitioner development initiatives. It aimed instead<br />

to stimulate critical reflection by teacher educators themselves, with project team<br />

members, by undertaking structured research activities that acted on concerns<br />

identified by DIET staff. Issues <strong>of</strong> accountability <strong>and</strong> autonomy were raised during<br />

this process, <strong>and</strong> proaction by DIET staff in generating their own research agenda<br />

to address their own concerns helped illustrate the possibilities for more<br />

autonomous action by DIET staff.<br />

xi DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

The processes <strong>of</strong> action research project design, collection <strong>and</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> data,<br />

assisted staff in reflecting on their own practices, <strong>and</strong> gaining clearer<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>of</strong> the issues teachers face, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> their own role in facilitating<br />

teacher development <strong>and</strong> engaging with issues. Stimulating this sense <strong>of</strong><br />

engagement emerges as central to making processes <strong>of</strong> practitioner development<br />

meaningful enough to result in changes to practice.<br />

DFID xii

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

xiii DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

0.1 Introduction<br />

The voluminous literature about teacher development pays comparatively little<br />

attention to the people who teach teachers – teacher educators. This is a consistent,<br />

but rather surprising omission given that, as Avalos (1991: 52) points out<br />

The best intentions <strong>of</strong> reform within teacher education programmes can<br />

founder if attention is not given also to improving the quality <strong>of</strong> teacher<br />

trainers.<br />

This report focuses on teacher educators in the context <strong>of</strong> a system <strong>of</strong> elementary<br />

education in India that has been decentralising <strong>and</strong> establishing a competencybased<br />

approach to teaching <strong>and</strong> learning since the early 1990s. Both were triggered<br />

by widespread concerns over unsatisfactory school enrolment <strong>and</strong> retention<br />

patterns, <strong>and</strong> underlying quality issues, that were leaving unfulfilled the<br />

constitutional pledge to provide all children with Universal Elementary <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> the quality debate has focused on teachers, <strong>and</strong> the nature <strong>of</strong> their<br />

training <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional identity – all <strong>of</strong> which have generally attracted negative<br />

commentaries (e.g. NPE 1986 / 92; PROBE 1999, Raina 1995, NCTE 1998c,<br />

1998d; UNICEF 1991, World Bank 1996).<br />

Following a national policy directive in 1986, two key institutional innovations<br />

were introduced to augment the previously limited resources for teacher<br />

education. In almost all <strong>District</strong>s across the country, a new structure at the<br />

<strong>District</strong> level was established – the <strong>District</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Training</strong> (DIET) – which reports to the previously established nodal institution<br />

at the State level, the State Council for <strong>Education</strong>al Research <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>,<br />

or equivalent. In selected <strong>District</strong>s only, under the <strong>District</strong> Primary<br />

<strong>Education</strong> Programme, Block <strong>and</strong> Cluster Resource Centres (BRCs <strong>and</strong> CRCs)<br />

were set up at the sub-<strong>District</strong> level. Cluster Resource Centres are now being<br />

rolled out across the system. These structural innovations <strong>of</strong>fer considerable<br />

potential for continuing pr<strong>of</strong>essional enrichment for elementary school<br />

teachers.<br />

0.2 Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan<br />

Introduction<br />

Over the years, several different schemes have been put in place to try <strong>and</strong> achieve<br />

Universal Elementary <strong>Education</strong>. Despite individual gains, this has contributed to<br />

a national scenario <strong>of</strong> fragmentation <strong>and</strong> overlap which is to be addressed through<br />

the creation <strong>of</strong> an overarching programme, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. The Sarva<br />

Shiksha Abhiyan embraces almost all existing schemes in order to achieve<br />

convergence <strong>and</strong> coherence.<br />

DFID 1

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Two <strong>of</strong> the external interventions that have provided a learning context for this<br />

project <strong>and</strong> which have now been subsumed into the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan are the<br />

<strong>District</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong> Programme (DPEP) <strong>and</strong> the Lok Jumbish project (see<br />

Boxes 0.1 <strong>and</strong> 0.2). The DPEP has for example encouraged decentralised, <strong>District</strong>based<br />

planning; enhanced community participation in schooling; provided new <strong>and</strong><br />

improved learning environments through extensive civil works programmes;<br />

improved the preparation, motivation <strong>and</strong> deployment <strong>of</strong> teachers through teacher<br />

training <strong>and</strong> teacher recruitment <strong>and</strong> deployment; strengthened management; <strong>and</strong>,<br />

through its textbook renewal programme, improved the quality <strong>of</strong> textbooks <strong>and</strong><br />

teaching <strong>and</strong> learning materials. Lok Jumbish has also furnished many insights into<br />

the challenges <strong>of</strong> developing meaningful community participation; <strong>and</strong> both <strong>of</strong> these<br />

programmes also underline a continuing need to strive towards gender equality.<br />

Challenges for the future under SSA are to draw the whole system into building<br />

on <strong>and</strong> consolidating from project gains – for example to improve planning so that<br />

is more holistic <strong>and</strong> locally consultative; to help teachers become better able to<br />

respond to multi-ethnic, multi-caste, multi-grade <strong>and</strong> multi-ability contexts; to<br />

improve the capacity <strong>of</strong> institutions that provide on-going technical <strong>and</strong><br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional support to teachers – such as SCERTs, DIETs <strong>and</strong> Cluster Resource<br />

Centres – <strong>and</strong> to continue to improve management capacity.<br />

DIETs are written large into the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan framework, <strong>and</strong> many <strong>of</strong><br />

its aspects require their involvement (DEEL 2002). This is an opportune moment<br />

to reflect on the performance <strong>of</strong> DIETs so far, <strong>and</strong> to identify ways in which they<br />

may be further strengthened <strong>and</strong> supported in pursuit <strong>of</strong> the many roles <strong>and</strong><br />

responsibilities intended for them in future.<br />

0.3 Project intentions <strong>and</strong> methodology<br />

Earlier research (Dyer 1994, 1996, 2000) had identified several gaps between the<br />

expectations <strong>of</strong> teachers articulated in policy discourses, <strong>and</strong> the situations<br />

observed on the ground in schools. That teacher education is implicated in<br />

sustaining rather than closing such gaps is made clear in <strong>of</strong>ficial commentaries, but<br />

there is little ethnographic description <strong>of</strong> processes <strong>of</strong> teacher education to draw<br />

on to explain from the (all too <strong>of</strong>ten neglected) practitioners’ points <strong>of</strong> view why<br />

this might be.<br />

The main concerns <strong>of</strong> this research have been to inform <strong>and</strong> guide policy making<br />

<strong>and</strong> practitioner development by:<br />

• providing otherwise absent ethnographic detail about educational processes in<br />

DIETs <strong>and</strong> related schools<br />

2 DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

• focusing on DIETs in relation to other educational institutions in a systemic<br />

context <strong>of</strong> decentralisation<br />

• engaging with the pressing question <strong>of</strong> teachers’ will to adopt change messages<br />

through a critique <strong>of</strong> the dominant training model, <strong>and</strong> exploration <strong>of</strong> a model<br />

based on collaborative practitioner reflection <strong>and</strong> action.<br />

0.3.1 Research with a commitment to action<br />

A two month pilot project <strong>of</strong> one DIET in 1996, funded by the University <strong>of</strong><br />

Manchester (Dyer <strong>and</strong> Choksi 1997) led to the DFID-funded study reported on<br />

here. The pilot project was invaluable in framing the substance <strong>and</strong> approach <strong>of</strong><br />

the longer one that followed. Substantively, it provided themes, issues <strong>and</strong><br />

concerns to follow up in a larger, longer <strong>and</strong> more in-depth project. The<br />

methodology <strong>of</strong> the larger project also grew from one key substantive finding <strong>of</strong><br />

the pilot: a lack <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development opportunities for DIET staff. We felt<br />

that a future project should attempt to respond to this gap, <strong>and</strong> wanted the larger<br />

project’s processes to be directed as much as possible by ‘research with’ which<br />

encouraged joint reflection <strong>and</strong> subsequent action in collaboration between DIETs<br />

<strong>and</strong> research team as a mode <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development. Ethically, we wanted to<br />

make a commitment to action, expecting that research would be more likely to<br />

‘make a difference’ if it draws people in as participants in shared research processes,<br />

rather than as subjects (or objects) <strong>of</strong> research carried out by outside ‘expert’<br />

researchers. The intention was thus to engage through action with issues that<br />

emerged, rather than restrict the research project focus to observing <strong>and</strong> reporting.<br />

0.3.2 Aims <strong>and</strong> objectives<br />

The project intended to provide a case study <strong>of</strong> policy innovation for teacher<br />

education (the innovation <strong>of</strong> DIETs) drawing on six sample <strong>District</strong>s to identify<br />

<strong>and</strong> illustrate larger trends <strong>and</strong> issues. The overall aim <strong>of</strong> the research was:<br />

Through the use <strong>of</strong> participatory methods, to evaluate the functioning <strong>of</strong> selected<br />

DIETs within the decentralised framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>District</strong> Planning initiatives; <strong>and</strong> to<br />

initiate where necessary, <strong>and</strong> otherwise support, a process by which the capacity <strong>of</strong> these<br />

institutions to meet their objectives is enhanced through critical reflection <strong>and</strong> action.<br />

In order to achieve this aim, the objectives <strong>of</strong> the research were:<br />

1 To appraise existing situations in selected elementary schools vis-à-vis physical<br />

conditions, clientele, availability <strong>of</strong> teaching-learning materials, teacher<br />

motivation, classroom management style, pedagogical approaches,<br />

administrative <strong>and</strong> pedagogical support, interaction with village communities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> so on.<br />

2 To analyse each DIET’s contribution to the pr<strong>of</strong>essional development <strong>of</strong><br />

teachers by examining:<br />

DFID 3

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

a) the extent to which pre-service education prepares teachers for the<br />

circumstances in which they will find themselves once in post<br />

b) the quality <strong>of</strong> in-service inputs <strong>and</strong> delivery mechanisms, <strong>and</strong> fit between<br />

training programmes <strong>and</strong> teachers’ perceived needs<br />

c) the capacity <strong>of</strong> each DIET to engage in research that relates to their own <strong>and</strong><br />

teachers’ needs.<br />

3 To assess each DIET’s internal managerial capacity <strong>and</strong> its external relationships<br />

with institutions in the <strong>District</strong> <strong>and</strong> other levels <strong>of</strong> the administrative hierarchy,<br />

in order to assess how well they are integrated into the strategy <strong>of</strong> universalising<br />

elementary education.<br />

4 To use research findings in a continuous process <strong>of</strong> providing support <strong>and</strong><br />

initiative to assist the development <strong>of</strong> capacity in DIETs, <strong>and</strong> to use this research<br />

project to strengthen <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> that capacity through both participation <strong>and</strong><br />

example, both at the <strong>District</strong> <strong>and</strong> other levels <strong>of</strong> the administration where<br />

stakeholders have been identified.<br />

These aims <strong>and</strong> objectives were conceptualised visually (Figure 0.1). This diagram<br />

served both as a comparative framework for a situation analysis across the sites,<br />

<strong>and</strong> as a reminder <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> relating the DIET to its surrounding<br />

context, rather than view it in isolation.<br />

There were two interwoven str<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> project activity. One was an ethnographic<br />

situation analysis <strong>of</strong> the DIET, structured round Figure 0.1 (reported on<br />

in chapters 1-6). The project team worked within the interpretive paradigm,<br />

using a range <strong>of</strong> qualitative methods such as interviews, participant observation<br />

(including longitudinal case studies <strong>of</strong> selected elementary schools), focus<br />

groups, open-ended questionnaires <strong>and</strong> document analysis. The second project<br />

str<strong>and</strong> broadly concerned pr<strong>of</strong>essional development for DIET staff <strong>and</strong> took<br />

several forms: collaborative action research projects with staff which <strong>of</strong>fered<br />

opportunities to reflect on working practices (chapter 7); an action research<br />

project with teachers to gain detailed insight into their developmental needs<br />

(chapter 8); <strong>and</strong> research commissioned by the Government <strong>of</strong> Gujarat into<br />

its cascade model <strong>of</strong> training, with a focus on future development <strong>of</strong> teacher<br />

educators (chapter 9).<br />

4 DFID

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

Figure 0.1: Situation analysis framework<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

inputs<br />

Human<br />

Financial<br />

NGOs<br />

DDO<br />

Internal<br />

Systemic Leadership<br />

DPEO<br />

CRC<br />

Resource<br />

dependency<br />

Management<br />

0.4 Site selection<br />

BRC<br />

Human<br />

Financial<br />

Policy<br />

documents<br />

Linkages<br />

outside<br />

DIET<br />

Resources<br />

within DIET<br />

Physical<br />

Values<br />

Calendar<br />

Activities<br />

PRESET,<br />

INSET, other<br />

branches<br />

DIET<br />

SITUATION<br />

ANALYSIS<br />

Institutional<br />

staffing<br />

Teamwork<br />

Co-operation<br />

Assumptions Underst<strong>and</strong>ings<br />

Action with<br />

teachers,<br />

schools<br />

Planning Expertise<br />

Impact <strong>and</strong><br />

relevance for<br />

clients<br />

<strong>Teacher</strong>s<br />

Students<br />

Schools<br />

Village<br />

communities<br />

Cluster/<br />

Block<br />

Resource<br />

Centres<br />

Other<br />

institutions<br />

Policy<br />

inputs<br />

Capacity<br />

building<br />

Two DIETs each were selected from the States <strong>of</strong> Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh <strong>and</strong><br />

Rajasthan, to gain a range <strong>of</strong> social <strong>and</strong> governmental contexts. An added<br />

dimension was the inclusion in each State <strong>of</strong> one DIET from a <strong>District</strong> where an<br />

external intervention was running (the <strong>District</strong> Primary <strong>Education</strong> Programme in<br />

Gujarat <strong>and</strong> Madhya Pradesh, see box 0.1) <strong>and</strong> the Lok Jumbish project in<br />

Rajasthan (see box 0.2). The other DIET in the State was internally resourced – a<br />

regular ‘government DIET’.<br />

Sample DIETs were selected in consultation with each apex State body.<br />

No preference for a particular DIET was shown, although in Rajasthan, the<br />

then Chairman <strong>of</strong> Lok Jumbish encouraged the team to work with Masuda<br />

DIET (Ajmer <strong>District</strong>), which he considered the best developed <strong>of</strong> the three<br />

DIETs adopted by Lok Jumbish. Otherwise, it was acknowledged that the vast<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> DIETs were not meeting expectations, <strong>and</strong> the project was expected to<br />

shed light on reasons for this. State-level <strong>of</strong>ficials in all three States were supportive<br />

<strong>and</strong> available for discussion <strong>and</strong> feedback throughout. For DIETs participating in<br />

the project, this would be a first experience <strong>of</strong> a process-orientated research<br />

approach, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> a project that intended to provide developmental support<br />

according to their priorities. There was openness towards these ideas <strong>and</strong><br />

widespread agreement <strong>of</strong> the need for support, although in practice the extent to<br />

DFID 5

<strong>District</strong> <strong>Institutes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Training</strong>: A Comparative Study in Three Indian States<br />

which DIETs saw the project as an opportunity <strong>and</strong> were able to make use <strong>of</strong><br />

it varied considerably.<br />

The two sites in Rajasthan were Udaipur <strong>and</strong> Ajmer <strong>District</strong>s. The situation<br />

analysis was completed in both these DIETs but pr<strong>of</strong>essional development<br />

activities were somewhat constrained in both <strong>of</strong> them, for different reasons. In<br />

Madhya Pradesh, two DIETs in the west <strong>of</strong> the State were selected. Indore DIET<br />

is a large <strong>and</strong> well established DIET in a large city; Dhar DIET is in the<br />

neighbouring, predominately tribal, <strong>District</strong>. All proposed activities could be<br />

undertaken in both these DIETs. Unfortunately, the team was not able to continue<br />

work with the pilot project DIET in Gujarat, owing to a change in leadership. Full<br />

access to the second intended sample DIET in Gujarat was also problematic<br />