The Ties That Bind: Tortfeasors and Family-Provided Care

The Ties That Bind: Tortfeasors and Family-Provided Care

The Ties That Bind: Tortfeasors and Family-Provided Care

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Ties</strong><br />

<strong>Bind</strong><br />

<strong>That</strong><br />

<strong>Tortfeasors</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Family</strong>-<strong>Provided</strong> <strong>Care</strong><br />

BY VENERANDA J. AGUIRRE<br />

18 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y M AY 2 0 1 0 w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g / A Z A t t o r n e y

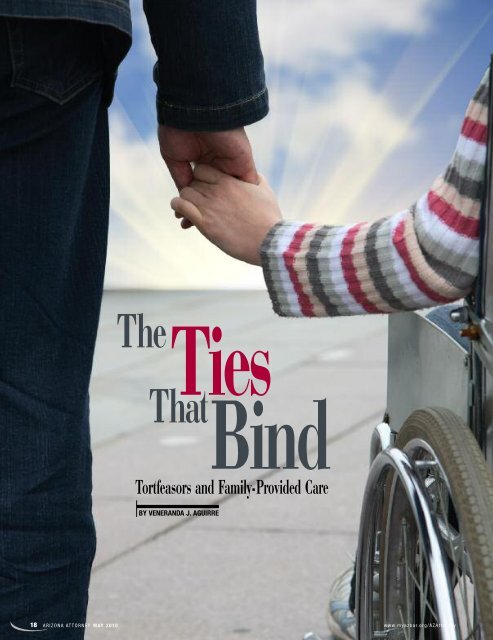

You are sitting at your desk when your<br />

phone rings. A woman on the other end of<br />

the line is seeking help for a loved one. Can<br />

they come in <strong>and</strong> see you? You set up an<br />

appointment <strong>and</strong>, days later, the woman<br />

wheels a man into your office. He wants to<br />

sue the City to recover his medical expenses.<br />

He’s not out for blood, he says. It’s just that<br />

someone failed to do their job properly, <strong>and</strong><br />

he took the fall, literally.<br />

<strong>The</strong> man describes how he was hit by<br />

falling debris from a municipal building construction<br />

project three stories above. He was<br />

badly injured by the debris <strong>and</strong> the subsequent<br />

fall, leaving him in a wheelchair for an<br />

unknown amount of time. Months have<br />

passed as he convalesced at the h<strong>and</strong>s of his<br />

devoted family caretaker. Now, they both are<br />

here to discuss recovery. He has medical bills<br />

but no long-term nursing care, as his family<br />

caretaker has assumed the role. She did so<br />

without any thought of compensation, missing<br />

weeks of work, just to see to all his needs.<br />

Is there any way, the man asks, that they<br />

can recover something for all the time this<br />

woman has cared for him, taken him to every<br />

doctor’s appointment, measured out his<br />

medicine, even helped him in <strong>and</strong> out of the<br />

bath?<br />

Arizona Law<br />

A review of Arizona case law yields three cases<br />

with similar results—but divergent theories.<br />

In City of Tucson v. Holliday, 1 the Arizona<br />

Court of Appeals ruled that a plaintiff should<br />

be compensated by the defendant for the<br />

gratuitous care she received from a family<br />

member based on the plaintiff’s duty to<br />

repay the favor to the gratuitous caretaker,<br />

<strong>and</strong> thus the defendant’s duty to reimburse<br />

the plaintiff for those same expenses.<br />

In Lopez v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 2 the<br />

Arizona Court of Appeals instead found that<br />

the fact that medical care was bestowed upon<br />

the plaintiff for free did not alleviate the<br />

defendant from paying for such care, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

the value of the care acted as a measure of<br />

damages for which the defendant must compensate<br />

the plaintiff.<br />

w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g / A Z A t t o r n e y<br />

In Carbajal v. Indus. Comm., 3 the<br />

Arizona Supreme Court, in looking at the<br />

narrow issue of workers’ compensation laws,<br />

found that it was the nature of the services<br />

provided, not the identity of the service<br />

provider, that mattered.<br />

<strong>The</strong> plaintiff in Holliday suffered various<br />

injuries when she wedged her shoe in a hole<br />

in a pedestrian crosswalk, created six months<br />

earlier by negligent municipal workers. On<br />

appeal, the court examined a trial jury<br />

instruction permitting the jury to award<br />

compensation for the reasonable value of<br />

services rendered to the plaintiff by her sister<br />

during her convalescence, even though the<br />

sister was never paid by the plaintiff for the<br />

services rendered. 4 <strong>The</strong> court approved of<br />

the recovery for the reasonable value of nursing<br />

care or services given to a plaintiff by a<br />

friend or relative without expectation of<br />

repayment. As the court reasoned:<br />

It is a well-known fact that persons wear<br />

out their “welcome” with friends <strong>and</strong><br />

even with relatives, unless favors are<br />

returned. <strong>The</strong> moral obligation to repay<br />

favors such as this is sufficient detriment<br />

to the plaintiff to support an award for<br />

the reasonable value of such services,<br />

providing they were made necessary by<br />

the injury wrongfully inflicted. 5<br />

In Lopez, the plaintiff slipped <strong>and</strong> fell<br />

while entering a Safeway store <strong>and</strong> sustained<br />

injuries. On appeal, the Arizona Court of<br />

Appeals examined whether Lopez was entitled<br />

to claim <strong>and</strong> recover the full amount of<br />

her reasonable medical expenses for which<br />

she was charged, even though some of the<br />

expenses were written off by the providers in<br />

conjunction with the insurance carrier. 6<br />

<strong>The</strong> court based its findings on the<br />

Restatement (Second) of Torts collateralsource<br />

rule, adopted after Holliday was<br />

decided. 7 <strong>The</strong> focal point of the collateralsource<br />

rule is not whether an injured party<br />

has “incurred” certain medical expenses,<br />

but rather whether a tort victim has benefited<br />

from a collateral source that cannot be<br />

used to reduce the amount of damages<br />

owed by a tortfeasor. 8<br />

VENERANDA J. AGUIRRE is a 2005 University of Arizona Law School graduate.<br />

She is currently in solo practice in Tucson, Arizona, <strong>and</strong> enjoys working<br />

in a variety of legal genres. Aguirre is an active member of the Junior League<br />

<strong>and</strong> works with independently living seniors, <strong>and</strong> volunteers for Organizing<br />

for America. She lives in Tucson with her husb<strong>and</strong> Daniel M<strong>and</strong>el, a software<br />

engineer for Apple, Inc.<br />

She can be reached at (520) 247-5610 or vene_aguirre@yahoo.com.<br />

<strong>The</strong> court explained that compensatory<br />

damages are meant to make a tort victim<br />

whole. 9 It is the tortfeasor who should make<br />

the victim whole <strong>and</strong> not a combination of<br />

the tortfeasor <strong>and</strong> collateral sources, such as<br />

health care providers. 10 To the extent that<br />

such a result provides a windfall to the<br />

injured party, the court acknowledged that<br />

the victim of the wrong should receive the<br />

windfall rather than the wrongdoer. 11<br />

In Carbajal, the plaintiff suffered an<br />

industrial injury that caused cognitive problems<br />

<strong>and</strong> partial paralysis, resulting in<br />

required full-time supervision <strong>and</strong> intermittent<br />

attendant assistance. His employer,<br />

Phelps Dodge, <strong>and</strong> its workers’ compensation<br />

carrier provided daily attendant care.<br />

Each weekday an attendant arrived at Mr.<br />

Carbajal’s home, helped him in his necessary<br />

duties <strong>and</strong> helped him perform simple exercises.<br />

<strong>The</strong> attendant also drove him to <strong>and</strong><br />

from a rehabilitation center. <strong>The</strong> rest of the<br />

time, <strong>and</strong> those times when the attendant did<br />

not arrive, Mrs. Carbajal was left to act as<br />

attendant to her husb<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Mrs. Carbajal sued the carrier for compensation<br />

for services provided under A.R.S.<br />

§ 23-1062(A). <strong>The</strong> Administrative Law<br />

Judge denied compensation, concluding that<br />

Mrs. Carbajal’s services were those “assumed<br />

by a spouse in accord with the marriage commitment.”<br />

12 <strong>The</strong> Court of Appeals denied<br />

Mrs. Carbajal’s claim based on what the<br />

Supreme Court would later call semantics. 13<br />

<strong>The</strong> Supreme Court instead granted Mrs.<br />

Carbajal’s claims, comparing the services she<br />

provided to those provided by the paid attendant.<br />

14 For the Court, it was not the identity<br />

of the service provider, but the nature of the<br />

services provided that determined the compensability<br />

of services. 15 <strong>The</strong> Court went on<br />

to hold that Mrs. Carbajal’s services were<br />

compensable under the statute.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Restatement<br />

<strong>The</strong> collateral-source rule, Section 920A(2)<br />

of the Restatement (Second) of Torts, states,<br />

“Payments made to or benefits conferred on<br />

the injured party from other sources are not<br />

M AY 2 0 1 0 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y<br />

19

<strong>Tortfeasors</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Family</strong>-<strong>Provided</strong> <strong>Care</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> majority of courts have<br />

taken the view that damages<br />

should be measured by the market rate, or by<br />

the amount for which reasonably competent<br />

care could be obtained from others.<br />

credited against the tortfeasor’s liability,<br />

although they cover all or a part of the harm<br />

for which the tortfeasor is liable.” 16<br />

In addition, § 924 of the Restatement<br />

provides that a tort victim may recover damages<br />

for “reasonable medical <strong>and</strong> other<br />

expenses.” Much like the collateral-source<br />

rule, comment f to § 924 states in part that:<br />

<strong>The</strong> injured person is entitled to damages<br />

for all expenses <strong>and</strong> for the value of<br />

services reasonably made necessary by<br />

the harm… . <strong>The</strong> value of medical services<br />

made necessary by the tort can ordinarily<br />

be recovered although they have<br />

created no liability or expense to the<br />

injured person, as when a physician<br />

donates his services.<br />

<strong>The</strong> language of these sections suggests<br />

that it is tort law’s intention for a defendant<br />

to pay for the costs associated with gratuitous<br />

care given to the injured party by a relative,<br />

<strong>and</strong> such care is recoverable by the caretaker.<br />

Other States’ Views<br />

In Kaiser v. St. Louis Transit Co., 17 the<br />

Missouri Supreme Court reasoned, using the<br />

theory of the collateral-source rule, that the<br />

plaintiff would have required the attendance<br />

of a paid nurse if his wife <strong>and</strong> daughter had<br />

not been able to nurse him, <strong>and</strong> such a gift<br />

was to the plaintiff <strong>and</strong> not for the benefit of<br />

the defendant. In Wright v. United States, 18<br />

using similar logic, a federal district court<br />

concluded that to rebate the gratuitous cost<br />

of familial care from the plaintiff’s award<br />

would in effect make the tortfeasor a thirdparty<br />

beneficiary of spouses’ duty to care for<br />

each other. In B<strong>and</strong>el v. Friedrich, 19 the New<br />

Jersey Supreme Court stated that the gratuitous<br />

provision of services by the plaintiff’s<br />

mother neither abated nor diminished the<br />

defendant’s obligation to pay full compensatory<br />

damages, which include the value of<br />

such services as a measure of the plaintiff’s<br />

lost capacity. Furthermore, the court said<br />

that the fact that the mother of the injured<br />

plaintiff was not obligated to provide the care<br />

did not bar the application of the collateralsource<br />

rule. 20<br />

Defendants have attempted to argue that<br />

relatives owe a duty to care for one another,<br />

<strong>and</strong>, therefore, courts should not award damages<br />

when a relative provides gratuitous care,<br />

such as when a parent cares for a child.<br />

Courts have overwhelmingly rejected this<br />

contention. 21 Courts have more specifically<br />

found that spouses are not legally bound to<br />

care for one another, <strong>and</strong> thus the gratuitous<br />

care they provide is recoverable. 22 Conversely,<br />

even where a husb<strong>and</strong> was found to owe a<br />

duty to his wife to provide care, at least one<br />

court nevertheless awarded the reasonable<br />

value of nursing services to the caretaker. 23<br />

Measure of Damages<br />

Lost Wages vs. Nursing Costs<br />

<strong>The</strong> majority of courts have taken the view<br />

that damages should be measured by the<br />

market rate, or by the amount for which reasonably<br />

competent care could be obtained<br />

from others. 24<br />

In Depouw v. Bichette, 25 a minority decision,<br />

the Ohio Supreme Court recognized<br />

that a majority of state <strong>and</strong> federal courts<br />

have determined that the value to be awarded<br />

as damages is not lost wages, but the cost<br />

of hiring an outside nurse to render the<br />

care. 26 Nevertheless, the court found that<br />

when an individual is injured by the negligence<br />

of another <strong>and</strong> requires assistance with<br />

basic daily functions, it is not unreasonable<br />

for a spouse to prefer the assistance of a<br />

loved one over that of a total stranger. 27 As a<br />

consequence of the defendant’s negligence,<br />

Mr. Depouw lost wages while caring for his<br />

wife, <strong>and</strong>, consequently, the marital income<br />

of the Depouws was reduced. 28 <strong>The</strong> court<br />

ruled that Mrs. Depouw should be able to<br />

recover for her husb<strong>and</strong>’s lost wages. 29 In<br />

essence, Mrs. Depouw received the benefit<br />

of her husb<strong>and</strong>’s care, the measure of which<br />

was the detriment their marital income<br />

incurred.<br />

Several jurisdictions have supported the<br />

plaintiff’s claim for the caretaker’s lost wages<br />

while the caretaker was providing assistance<br />

to the plaintiff. 30 Courts, in granting lost<br />

wages, have looked for solid evidence of the<br />

actual loss incurred by the family. 31 In those<br />

cases where lost wages are speculative, such<br />

as where a caretaker is self-employed, courts<br />

have been reluctant to award damages based<br />

on lost earnings. 32 Some courts also have<br />

placed limits on the amount of recoverable<br />

lost wages to what would have been expended<br />

had a nurse been hired to care for the<br />

injured party. 33<br />

Skilled vs.Unskilled Nursing <strong>Care</strong><br />

Where jurisdictions have sided with the<br />

majority <strong>and</strong> ruled that the measure of damages<br />

is the market rate of nursing care, trial<br />

courts have been presented with the issue of<br />

valuing such care. Some courts have preferred<br />

to measure the damages by the st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

of skilled nurses. 34 Others, however,<br />

have limited the amount of recovery to the<br />

reasonable value of nursing by a person of<br />

ordinary <strong>and</strong> untrained skill. 35 <strong>The</strong>re does<br />

not appear to be an overriding majority<br />

opinion among the courts as between skilled<br />

or unskilled nursing care damages, nor have<br />

courts offered their reasoning for granting<br />

one or the other.<br />

Final Analysis<br />

Based on the research, your analysis leads<br />

you to the following: Though Holliday is a<br />

case directly on point, Lopez is a more recent<br />

case that reflects general principles of law.<br />

Both cases are valuable to your client’s claim.<br />

Holliday st<strong>and</strong>s for the principle that familial<br />

care creates a burden on the plaintiff that<br />

must be paid back by the defendant, <strong>and</strong><br />

Lopez builds the framework for recovery<br />

based on the collateral-source rule, stating<br />

that the tortfeasor should not benefit from<br />

the gratuitous acts of another. Carbajal,<br />

while limited to workers’ compensation<br />

20 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y M AY 2 0 1 0 w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g / A Z A t t o r n e y

claims, adds another<br />

layer to the foundation<br />

that family<br />

members should be compensated for care<br />

they provide, by focusing on the care given,<br />

instead of who the caregiver is.<br />

With regard to the type <strong>and</strong> amount of<br />

damages, because there is no governing law<br />

in this matter, it is best to argue for damages<br />

based on the facts of your client’s case. First,<br />

calculate the caretaker’s total lost wages as<br />

well as what it would cost to hire an<br />

unskilled <strong>and</strong> skilled nurse for your client’s<br />

endnotes<br />

<strong>Tortfeasors</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Family</strong>-<strong>Provided</strong> <strong>Care</strong><br />

1.411 P.2d 183 (Ariz. Ct. App. 1966).<br />

2.129 P.3d 487 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2006).<br />

3.2009 WL 1650428 (Ariz. Sup. Ct. June 15, 2009).<br />

4.411 P.2d at 194.<br />

5.Id.<br />

6.Based on information provided by Lopez, Safeway pointed out that,<br />

although Lopez’ medical bills totaled approximately $59,700, more<br />

than $42,000 of that was completely written off as adjustments.<br />

Safeway argued that Lopez should only be able to claim <strong>and</strong> present<br />

evidence on the $16,837 actually accepted in full satisfaction of the<br />

services rendered.<br />

7.Lopez, 129 P.3d at 491. Taylor v. S. Pac. Transp. Co., 637 P.2d 726,<br />

729-730 (Ariz. 1981), was the first Arizona case to formally adopt the<br />

collateral-source rule, but it did not involve gratuitous caretaking.<br />

8.Lopez, 129 P.3d at 492.<br />

9.Id. at 496.<br />

10. Id.<br />

11. Id. at 497.<br />

12. 2009 WL 1650428, 4.<br />

13. Id. 9-15.<br />

14. Id. 19.<br />

15. Id.<br />

16. Comment b to this section states:<br />

Payments made or benefits conferred by other sources are known as<br />

collateral-source benefits. <strong>The</strong>y do not have the effect of reducing the<br />

recovery against the defendant. … [T]o the extent that the defendant<br />

is required to pay the total amount [of the recovery] there may be a<br />

double compensation for a part of the plaintiff’s injury. But it is the<br />

position of the law that a benefit that is directed to the injured party<br />

should not be shifted so as to become a windfall for the tortfeasor… .<br />

If the benefit was a gift to the plaintiff from a third party … he should<br />

not be deprived of the advantage that it confers… . One way of stating<br />

this conclusion is to say that it is the tortfeasor’s responsibility to<br />

compensate for all harm that he causes, not confined to the net loss<br />

that the injured party receives… . Perhaps there is an element of punishment<br />

of the wrongdoer involved… . Perhaps also this is regarded as<br />

a means of helping to make the compensation more nearly compensatory<br />

to the injured party.<br />

Comment c(3) states that the collateral-source rule applies to the<br />

rendering of services as well. For example, the fact that a doctor did not<br />

charge for his services does not prevent the plaintiff’s recovery of the<br />

reasonable value of the services from the defendant.<br />

17. 84 S.W. 199 (Mo. 1904).<br />

18. 507 F. Supp. 147 (E.D. La. 1981).<br />

19. 584 A.2d 800 (N.J. 1991).<br />

period of convalescence. If total lost wages<br />

exceed all market-rate amounts, argue for<br />

lost wages. Keep in mind, however, that<br />

some courts have capped lost wages at market<br />

rate amounts.<br />

If, however, market rates exceed total lost<br />

wages, or if lost wages are vague or difficult<br />

to calculate, then consider the amount of<br />

skill involved in caring for your client. If the<br />

caretaker had to acquire special skills, such as<br />

learning how to administer certain drugs<br />

intravenously, then you might have an argument<br />

for skilled nursing care damages.<br />

Otherwise, it is uncertain whether a court<br />

would grant skilled or unskilled market rates,<br />

<strong>and</strong> you will argue that Arizona should follow<br />

California’s <strong>and</strong> Texas’ lead <strong>and</strong> grant<br />

skilled nursing care rates.<br />

You are satisfied that your client has a<br />

meritorious claim to bring against the City<br />

for damages including the gratuitous care.<br />

While the City cannot give you your client’s<br />

months of pain <strong>and</strong> suffering back, it is now<br />

likely that your client will be made more<br />

whole <strong>and</strong> that his tortfeasor will be more<br />

AZ<br />

thoroughly punished. AT<br />

20. Id.<br />

21. See, e.g., Hanif v. Housing Authority, 246 Cal. Rptr. 92 (1988). In<br />

Hanif, a California personal injury action by a child struck by an automobile,<br />

the court of appeals affirmed the trial court’s award of special<br />

damages, notwithst<strong>and</strong>ing the defendants’ arguments that parents have<br />

a legal duty to provide care to their children or that they rendered the<br />

services without an agreement or expectation of payment. See 49<br />

A.L.R. 5th 685 (1997), § 10. In a few parent/child cases, however,<br />

some courts have prohibited recovery for parental care, limiting damages<br />

to what care the parent can show goes beyond the care normally<br />

incidental to the relationship between parents <strong>and</strong> their children. See<br />

id. § 9.<br />

22. See Rodriguez v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 11 Cal. Rptr. 399 (1978);<br />

Str<strong>and</strong> v. Grinell Auto Garage Co., 113 N.W. 488 (Iowa 1907).<br />

23. Van House v. Canadian N. R. Co., 192 N.W. 496 (Minn. 1923).<br />

24. See Depouw v. Bichette, 833 N.E.2d 744, 747 (Ohio 2005), for a discussion<br />

of the majority opinion. See also B<strong>and</strong>el v Friedrich, 584 A.2d<br />

800 (N.J. 1991); Walker v. Philadelphia, 45 A. 657 (Pa. 1900);<br />

Richter v. North American Van Lines, Inc., 110 F. Supp. 2d 406 (D.<br />

Md. 2000); Rodriguez, 11 Cal. Rptr. at 399; Wright v. United States,<br />

507 F. Supp. at 147; Chicago D. & G.B. Transit Co. v. Moore, 259 F.<br />

490 (6th Cir. 1919); Scanlon v. Kansas City, 81 S.W.2d 939 (Mo.<br />

1935); Rouse v. Riverside Methodist Hospital, 459 N.E.2d 593 (Ohio<br />

1983).<br />

25. 833 N.E.2d 744 (Ohio 2005).<br />

26. Id. at 747.<br />

27. Id at 747-748.<br />

28. Id.<br />

29. Id. at 748.<br />

30. See Shurk v. Christensen, 497 P.2d 937 (Wash. 1972). See also Fields v.<br />

Graff, 784 F. Supp. 224 (E.D. Pa. 1992); <strong>and</strong> Lester v. Dunn, 47 F.2d<br />

983 (D.C. Cir. 1973), applying Maryl<strong>and</strong> law.<br />

31. See Kerns v. Lewis, 227 N.W. 727 (Mich. 1929). In Kerns, testimony<br />

that the husb<strong>and</strong>/plaintiff’s employer had hired another at the wage<br />

of $11 per day, <strong>and</strong> that the plaintiff had spent approximately six<br />

months at home caring for his wife before she died, was held sufficient<br />

to furnish a basis for evaluating his damages. See also Depouw, 833<br />

N.E.2d at 744. In Depouw, the calculable loss was 12 days of vacation<br />

time lost by a husb<strong>and</strong> due to caring for his wife.<br />

32. See Fargason v. Pervis, 227 S.E.2d 464 (Ga. 1976).<br />

33. See Becker v. Doble, 134 A. 154 (Conn. 1926). See also Byrne v. Pilgrim<br />

Med. Group, Inc., 44 A.2d 920 (N.J. 1982).<br />

34. See Ft. Worth & D.C.R. Co. v. Walker, 106 S.W. 400 (Tex. 1907). See<br />

also Hanif, 246 Cal. Rptr. at 92.<br />

35. See MacDonald v. St. Louis Transit Co., 83 S.W. 1001 (Mo. 1904). See<br />

also Pressy v. Patterson, 898 F.2d 1018 (5th Cir. 1990).<br />

22 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y M AY 2 0 1 0 w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g / A Z A t t o r n e y