Courbet's Exhibitionism

Courbet's Exhibitionism

Courbet's Exhibitionism

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COURBET' S EXHIBITIONISM<br />

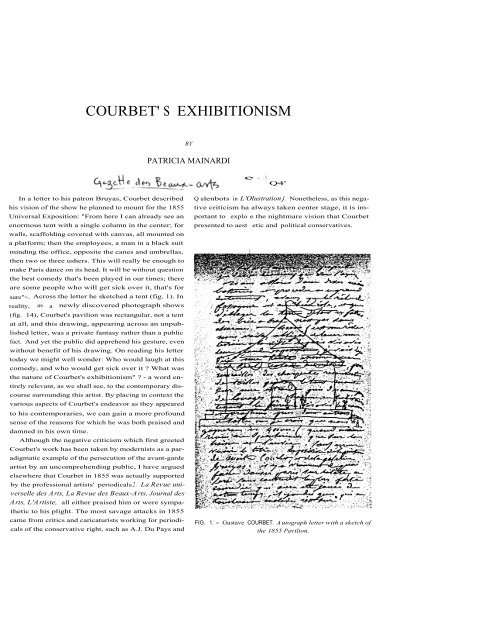

In a letter to his patron Bruyas, Courbet described<br />

his vision of the show he planned to mount for the 1855<br />

Universal Exposition: "From here I can already see an<br />

enormous tent with a single column in the center; for<br />

walls, scaffolding covered with canvas, all mounted on<br />

a platform; then the employees, a man in a black suit<br />

minding the office, opposite the canes and umbrellas,<br />

then two or three ushers. This will really be enough to<br />

make Paris dance on its head. It will be without question<br />

the best comedy that's been played in our times; there<br />

are some people who will get sick over it, that's for<br />

sure"~. Across the letter he sketched a tent (fig. 1). In<br />

reality, as a newly discovered photograph shows<br />

(fig. 14), <strong>Courbet's</strong> pavilion was rectangular, not a tent<br />

at all, and this drawing, appearing across an unpub-<br />

lished letter, was a private fantasy rather than a public<br />

fact. And yet the public did apprehend his gesture, even<br />

without benefit of his drawing. On reading his letter<br />

today we might well wonder: Who would laugh at this<br />

comedy, and who would get sick over it ? What was<br />

the nature of <strong>Courbet's</strong> exhibitionism" ? - a word en-<br />

tirely relevant, as we shall see, to the contemporary dis-<br />

course surrounding this artist. By placing in context the<br />

various aspects of <strong>Courbet's</strong> endeavor as they appeared<br />

to his contemporaries, we can gain a more profound<br />

sense of the reasons for which he was both praised and<br />

damned in his own time.<br />

Although the negative criticism which first greeted<br />

<strong>Courbet's</strong> work has been taken by modernists as a par-<br />

adigmatic example of the persecution of the avant-garde<br />

artist by an uncomprehending public, I have argued<br />

elsewhere that Courbet in 1855 was actually supported<br />

by the professional artists' periodicals 2 . La Revue universelle<br />

des Arts, La Revue des Beaux-Arts, Journal des<br />

Arts, L'Artiste, all either praised him or were sympa-<br />

thetic to his plight. The most savage attacks in 1855<br />

came from critics and caricaturists working for periodi-<br />

cals of the conservative right, such as A.J. Du Pays and<br />

BY<br />

PATRICIA MAINARDI<br />

e - 1 Q4'<br />

Q ulenbots in L'Olustrationj . Nonetheless, as this nega-<br />

tive criticism ha always taken center stage, it is im-<br />

portant to explo e the nightmare vision that Courbet<br />

presented to aest etic and political conservatives.<br />

FIG. 1. - Gustave COURBET. Autograph letter with a sketch of<br />

the 1855 Pavilion.

254<br />

Today we focus on <strong>Courbet's</strong> gesture of mounting<br />

his show and we see it as a gesture of defiance to the<br />

government that had rejected both his Studio and his<br />

Burial; indeed it was, as Champfleury wrote at the time,<br />

"an incredibly audacious act" 4 . Our focus on the gesture<br />

fits in well with modem political imperatives, the heroicization<br />

of the individual standing alone against an unjust<br />

state. The issues embodied in <strong>Courbet's</strong> gesture,<br />

Individualism, Self-confidence, Defiance, Genius, are<br />

all qualities which define the modern - usually male -<br />

hero. They are also, however, qualities which define the<br />

self-made man of early capitalism, the entrepreneur.<br />

FIG. 2. - Title Page, Catalogue of <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 Exhibition.<br />

GAZETTE DES BEAUX-ARTS<br />

This latterlreferent has been largely ignored by art historians,<br />

but both interpretations, defiant hero and entrepreneur,<br />

should be explored, for in the nineteenth<br />

century, they were by no means mutually exclusive.<br />

To begin to see <strong>Courbet's</strong> exhibitionism as his contemporarie''s<br />

would have seen it, we will have to understand<br />

firstl, the exhibition structure as they saw it,<br />

second, traditional exhibition sites as they understood<br />

them, and third, the decorum of exhibitions at that time,<br />

for <strong>Courbet's</strong> gesture could only assume meaning<br />

against the commonly accepted fabric of expectations<br />

and procedures. In giving the broad outlines of these<br />

issues, it trust be stressed that, although I am here focusing<br />

on the negative, contemporary opinion held<br />

various attitudes, both positive and negative, towards<br />

each.<br />

Throu0out most of the nineteenth century, the major<br />

event in I-Irench exhibition practice was the Salon, the<br />

annual, sometimes biennial, exhibition of contemporary<br />

art. Until the 1789 Revolution, it had operated as a monopoly,<br />

controlling French artistic life and careers. Only<br />

members Of the Academy could participate and alternative<br />

exhibitions were suppressed. The Academy had<br />

been founded and was maintained as the Government<br />

agency in charge of aesthetics: its members received<br />

salaries a~d studios, and State commissions were originally<br />

reserved for them. Academicians had, however,<br />

elevated their status from that of artisans by rejecting<br />

all hints f commerce and so, in the Academic Salon<br />

of the An ien R6gime, artists did not exhibit works for<br />

sale but "consented to show to a limited public some<br />

pictures commissioned in advance for a specific destination"<br />

5 . !,,Although in reality many Academicians<br />

worked inja variety of modes, this elite attitude towards<br />

art production survived well into the nineteenth century,<br />

defining o~e pole of the spectrum of attitudes towards<br />

exhibition Ipractice. That pole can be summed up in the<br />

word exposition; in both English and French it preserved<br />

thelconnotation of a didactic, morally instructive<br />

show. The word exhibition, on the other hand, while<br />

meaning lin English simply a show, assumed in<br />

nineteenth] century France a pejorative connotation of<br />

ostentation and immodesty. A commercial enterprise,<br />

such as a<br />

as would<br />

hibitionist<br />

hop window display, would be an exhibition,<br />

rsonal behaviour we today would label ex-<br />

This negative attitude towards anything<br />

commercial derived from traditional aristocratic disdain<br />

for corn*rce, which, in the nineteenth century, was<br />

identified ]with England, the leading commercial power<br />

among nations; hence the pejorative use of the English<br />

word exhibition 7. Needless to say, conservative critics<br />

descri<br />

not ai<br />

headi<br />

(fig.<br />

a dish<br />

Ai<br />

mono<br />

princ<br />

the P<br />

ing t(<br />

and i<br />

worl,<br />

Cour<br />

trout<br />

led i<br />

pron<br />

of e<br />

Salo<br />

ser\<br />

whi<br />

indi<br />

peal<br />

ab<br />

den<br />

ech<br />

ass<br />

bay<br />

in()<br />

sat<br />

ha~<br />

we<br />

do<br />

we<br />

th,<br />

to,<br />

re,<br />

si<br />

pr<br />

its<br />

w<br />

th<br />

tt<br />

n<br />

0<br />

l.<br />

d<br />

i

described <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 show as an "exhibition" and<br />

not an "exposition". Courbet himself provoked this by<br />

heading his own catalogue EXHIBITION ET VENTE<br />

(fig. 2) "Exhibition and Sale", a title more fitting for<br />

a display of furniture or rugs than of high art s .<br />

After the 1789 Revolution, the Academy had lost its<br />

monopoly over the Salon, which was then opened, in<br />

principle at least, to independent artists. Nonetheless,<br />

the Academy continued to maintain that it was degrading<br />

to make a direct appeal to the public to sell pictures,<br />

and that true artists did not produce easel paintings but<br />

worked on commission for Church and State. The young<br />

Courbet made his entrance to the Salon during the<br />

troubled years of the 1840s when the Academy controlled<br />

the Salon Jury, rejecting works by artists even as<br />

prominent as Delacroix. By the 1848 Revolution, out<br />

of eighteen paintings Courbet had submitted to the<br />

Salon, only two had been accepted.<br />

The 1830s and 1840s were the years in which conservatives<br />

began to criticize the Salon in language<br />

which continued throughout the century as an infallible<br />

indicator of conservative politica 9 . Ingres stated repeatedly:<br />

"The Salon is no longer anything more than<br />

a bazaar, where mediocrity displays itself with impudence"<br />

i0. E.J. Delecluze, the leading conservative critic,<br />

echoed his sentiments: "The Salons in the Louvre have<br />

assumed, more and more each year, the character of a<br />

bazaar, where each merchant is obliged to present the<br />

most varied and bizarre objects in order to provoke and<br />

satisfy the fantasies of his customers" Il . Art historians<br />

have largely ignored the significance of these code<br />

words: exhibition, market, picture shop, bazaar (exhibition,<br />

marche, boutique de tableaux, bazar) pejorative<br />

words never used by critics supportive of what we call<br />

the avant-garde.<br />

Conservatives believed that art was inherently aristocratic<br />

and elitist and that, under a democratic political<br />

regime, mediocrity would reign. Education, they insisted,<br />

was the only legitimate purpose for art, history<br />

painting its only legitimate vehicle, and Academicians<br />

its only legitimate practitioners; the habitus of such art<br />

was the church, the public monument, the museum or<br />

the aristocratic private gallery. The enemy for them was<br />

the bourgeois preference for art as decoration or as commodity.<br />

Such art, they felt, was trivial and commercial,<br />

only fit to be sold at bazaars and market places. Their<br />

language was anachronistic, however, for, as capitalism<br />

leveloped, the site of art distribution became increasngly<br />

the commercial art gallery or the auction house.<br />

through this politico-aesthetic language, of bazaars and<br />

)icture shops, of mediocrity and aristocracy, a political<br />

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM 25 5<br />

la do d. Yon E:poeiW~e anlyeraeile, Cooabet Re dtoeioe ! lal-mama<br />

quolquaa rdeompewa Lle~ mfritfea, on prlsence rune multitude choide,<br />

compacts de M. Bra et ton ehiso. -<br />

FIG. 3. - BERTALL in the Journal pour tire, 12 January 1856.<br />

system - democracy I-and an economic system - capitalism<br />

- was being criticized: Courbet, through his 1855<br />

show, symbolized bh institutions.<br />

It is clear that 11855 the two poles of the Salon<br />

were, on the right, elevated, academic exhibition as<br />

close as possible tot the ideals of history painting and<br />

the Ancien Mgime.lOn the left there was the popular<br />

Salon, full of inde p ,~ ndept artists striving to appeal to<br />

the public in order to sell their work. But if, in fact,<br />

the other pole fromIthe aristocratic closed pre-Revolutionary<br />

Salon was tolbe the open, somewhat democratic<br />

and independent Sal n, where does that place <strong>Courbet's</strong><br />

pavilion ? When con ervatives referred to a bazaar, they<br />

were both exaggera ing and speaking metaphorically;<br />

Courbet intentional, produced the very image of their<br />

nightmare, but not i the quaint, sentimentalizing imagery<br />

of a bygone e och, of marche and bazar, but in<br />

the contemporary wo Id of burgeoning mass culture and<br />

commercialism - thel art exhibition as store.

25 6<br />

To place <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 show, we must understand<br />

how rare any individual shows were in France. The most<br />

common examples of these events were the posthumous<br />

shows organized for recently deceased Academicians<br />

and held in prestigious locations such as the Ecole itself.<br />

Galleries at this time were still picture shops displaying<br />

and selling a variety of work by a variety of<br />

artists. Artists occasionally held their own shows in<br />

their studios, as David did in 1799 and Horace Vernet<br />

in 1822, but, by being held in their studios, these shows<br />

preserved the dignity of hiO art events, even when they<br />

were intended as protest t . <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 show has<br />

always been identified with this tradition, a protest<br />

against the Exposition Jury's refusal of his two major<br />

pictures, The Artist's Studio and A Burial at Ornans<br />

(figs. 12 and 13). And yet even before he submitted his<br />

pictures to the Jury' he had informed Nieuwerkerke, the<br />

Intendant des Beaux-Arts, that he was hoping to mount<br />

a private exhibition to compete with the Universal Ex-<br />

GAZETTE DES BEAUX-ARCS<br />

position, land he had dropped several hints to his patron<br />

Alfred Blruyas that such a show (which he wanted<br />

Bruyas to subsidize) was in the offing l 3. One could<br />

argue that he anticipated that his pictures would be rejected,<br />

but it must also be acknowledged that he very<br />

much wanted, from the beginning, to hold this show<br />

and to hold it on a site identified with the distribution<br />

of art and not its production, in other words, to hold it<br />

as a commercial enterprise. Indeed he had already made<br />

two previlous attempts in this direction in 1850, in Besanrgon<br />

and in Dijon, the first in a market hall, the second<br />

in mouse that also held a cafe. In both cases he<br />

had plastered the town with posters advertising his show<br />

and had charged a fifty centime admission fee t4 . Riat<br />

quotes him as feeling that the peasantry of Omans had<br />

thought he was an idiot because he had let them see<br />

his works! for free, "which evidently proves it's silly to<br />

have a kind heart, for it merely deprives one of funds<br />

without enriching others in spirit or purse. To be free,<br />

"Lis 0Z gBAID®S4lltflI5<br />

4.Tmm wjb~ W. lost I M-11<br />

FIG. 4. - J. JOURDAN, Le Palais de l'Industrie, Tutgis Editeur, Paris, 1855.<br />

peo<br />

swa<br />

so<br />

to t<br />

loc;<br />

in<br />

mu<br />

be,<br />

mo<br />

wh<br />

tale<br />

mu<br />

in<br />

art<br />

ye<br />

ins<br />

in<br />

tip<br />

ha<br />

te-<br />

B(<br />

di<br />

a<br />

fc<br />

tl<br />

a,<br />

R<br />

c<br />

V<br />

p<br />

e<br />

f<br />

I

eople want to pay, so that their judgment won't be<br />

Hayed by gratitude; they are right. I want to learn and<br />

I'll be so ruthless that I'll give everyone the right<br />

15 .<br />

tell me the most cruel truths"<br />

This leads to my second point, the issue of a suitable<br />

)cation for art exhibitions. The annual Salon took place<br />

I the Louvre until 1848 when, evicted from the<br />

tuseum, it began a nomadic existence l 6. Pressure had<br />

egun to mount in the 1830s to evict it from the Louvre,<br />

Iostly coming from conservatives who felt that art<br />

,hich increasingly rejected tradition had no right to par-<br />

Ike of the elevated provenance associated with that<br />

tuseum. The Salons of 1849, 1850-51, 1852, were held<br />

1 the Tuileries and in the Palais-Royal; 1853 presented<br />

rtists with the worst disappointment of all, for that<br />

ear's Salon was held in temporary buildings surround-<br />

Ig the Imperial furniture warehouse at Menus-Plaisirs<br />

i northern Paris. During these years there was con-<br />

,nual talk of suppressing the Salon altogether; Ingres<br />

ad actually recommended such a course when he<br />

:stified before the 1848 Commission permanente des<br />

ieaux-Arts: "In order to remedy this overflow of me-<br />

. iocrities, which has resulted in there no longer being<br />

French School, this banality which is a public misortune,<br />

which afflicts taste, and which overwhelms<br />

he administration whose resources it absorbs to no<br />

vail, it would be necessary to give up expositions..." 17<br />

tumors and uncertainty ran rife through the artists'<br />

ommunity. Would there continue to be a Salon ? If so,<br />

vhere would it be held ? The very future of contem-<br />

>orary art seemed to be at stake during these years, so<br />

'.ourbet's carnival tent would not seem very funny to<br />

hose who feared that contemporary art might end up<br />

xactly there.<br />

Art galleries as we know them were still in their inancy<br />

in the first half of the century. In 1843 the critic<br />

.outs Peisse wrote: "Outside the Louvre there would<br />

Io Ion Rer be a Salon, there would be only picture<br />

,hops" i8. Galleries were then indeed picture shops seling,<br />

indiscriminately, art supplies, curios, and small<br />

>ictures from the lower categories of art - genre, land-<br />

:cape, still life l9 . The common conservative complaint<br />

hat the Salon had become a bazaar or a picture shop<br />

,howed that, in fact, these institutions were seen as the<br />

mly alternative to the museum. So the two poles on<br />

he exhibition spectrum were the Louvre, for exposiions<br />

of educational, historical art, and the picture shop<br />

'or exhibitions of commercially viable, decorative art.<br />

knd yet art dealers at this time were not interested in<br />

)old entrepreneurial initiatives, such as the promotion<br />

Ind marketing of a trademarked product, namely the<br />

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM 257<br />

FIG. 5. - Auguste BELIN. "Sortie du Bat de 1' Opdra", Journal<br />

amu$ant, January 1859.<br />

b¢uf 6wt la r~iarrac qiu est tratnh pat lea labor<br />

FIG. 6. - Le Monde Renverse, Pellerin Imprimeur, Epinal, 1829.

25 8<br />

t

in France. It was only because of David's great celebrity,<br />

and the extreme curiosity that his work aroused,<br />

that the public accepted a practice which is repugnant<br />

to all our French customs. Although this mode of exposition<br />

succeeded in that David earned 20,000 francs,<br />

he was harshly criticized, and ever since no artist has<br />

dared try it again"23 . In the heated polemics accompanying<br />

the introduction of admission fees at the 1855 Universal<br />

Exposition, the standard objection was to stress<br />

that, under the longstanding policy of noblesse oblige,<br />

a benevolent state owed to its citizens free access to<br />

those institutions considered spiritually and morally<br />

uplifting, such as churches, schools, libraries, public<br />

monuments, and expositions. Charging admission fees,<br />

it was feared, would lower art exhibitions to the level<br />

of popular entertainment, like theatres 24. Courbet, however,<br />

blatantly moved art into this sphere of commercial<br />

entertainment and self-promotion, with his pavilion<br />

advertising his own name G. Courbet (visible in<br />

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM 25 9<br />

FIG. 9. - Gustave COURBET. Les Demoiselles de Village, Salon of 1852. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Harry Payne<br />

Bingham, 1940.<br />

fig. 14), as prominently as did the bold red signatures<br />

on his paintings 25 . Charles Perrier, the critic for L'Artiste,<br />

commented Iveryone has seen Monsieur <strong>Courbet's</strong><br />

poster with it$ huge lettering plastered over the<br />

walls of Paris, next o street performers and quack doctors,<br />

inviting the pu~lic to come and pay a franc to see<br />

his exhibition of tlorty pictures of his own work26 .<br />

Bertall's cartoon (fig. 3) "At the end of the Universal<br />

Exposition, Courbet! awards himself some well-merited<br />

honors" criticizes the artist both for commercialism (the<br />

receipt box is prominently displayed) and for immodesty<br />

(he is awardingI himself a laurel wreath). The critic<br />

Ernest Gebauer attacked Courbet in 1855 thus: "M.<br />

Courbet, not satisfied with having eleven pictures in the<br />

Universal Expositio , indulged himself by setting up his<br />

own special exhibition a few steps from Palais des<br />

Beaux-Arts" 27. In other words <strong>Courbet's</strong> show manifested<br />

the requisite commercialism, ostentation, and immodesty<br />

which defined it as an exhibition.

26 0<br />

In addition to the commerce of the picture shop,<br />

<strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 show also recalled the outdoor fairs, the<br />

immediate predecessors of the resolutely non-commercial,<br />

dignified Salon exhibitions. These lowly antecedents<br />

to the Salon continued to be an unwelcome<br />

memory of the past in the collective memory of Academicians<br />

and conservatives in general; hence their<br />

criticism of the Salon as a bazaar. Joined to this, however,<br />

was an even more frightening spectre of the future:<br />

the commercialization and commodification of art<br />

which, they feared, would happen under capitalism. In<br />

other words, to conservatives <strong>Courbet's</strong> show represented<br />

the worst of both the old and the new systems<br />

of art distribution. For us today it is less shocking and<br />

more laudable to see Courbet raging against an unjust<br />

State than to see him making a crassly commercial gesture.<br />

But to nineteenth century conservatives, it was the<br />

disturbing commercialism of his gesture rather than its<br />

political content that was shocking. After all, in 1855<br />

the political opposition came from both left and right;<br />

with the repeated revolutions and counter-revolutions<br />

which had shaken France since 1789, almost everyone<br />

had had a taste of being in the political opposition at<br />

some time.<br />

II. <strong>Courbet's</strong> <strong>Exhibitionism</strong> as Carnival<br />

GAZETTE DES BEAUX-ARTS<br />

Although I have been reading <strong>Courbet's</strong> exhibitionism<br />

as a function of capitalism and the new economic<br />

and social order, this should be underscored by a second<br />

level of interpretation which compounds the first: <strong>Courbet's</strong><br />

exhibitionism as carnival. If the Louvre, the Palace<br />

FIG. 10. - Gustave COURBET. Le Retour de la<br />

Confirence, 1862. Destroyed.<br />

of ings, represented the aristocratic tradition, and the<br />

Palace of Industry (fig. 4) at the Universal Exposition<br />

represented the challenge launched by capitalism, then<br />

Co rbet's pavilion can be seen as disruptive of both<br />

orders. Carnival, of course, did exactly that. Carnival,<br />

thel period from Twelfth Night (6 January) to Ash Wedne0ay<br />

of each year, culminating in the revelry of Mardi<br />

Gras, celebrated the world-upside-down, the reversal of<br />

thel normal order of events. It was filled with feasting<br />

and drunkenness, dancing and orgies, masquerades and<br />

street theatre. Inversion was its basic premise, satire and<br />

pa ody its means: the lowly were raised up and the<br />

mi hty were abased; social, political, and moral order<br />

cold be safely transgressed. Carnival during the 1830s<br />

an~i 40s had become increasingly political; no one at<br />

-century had forgotten that the February Revolution<br />

of': 1848 had taken place during Carnival and that the<br />

two events had been intertwined in a grotesquely surrealist<br />

spectacle: carnival processions turned into mob<br />

2s<br />

ri<br />

N<br />

U<br />

atmosphere, must be seen as the very antithesis of that,<br />

rigidly controlled and organized. This fact is important<br />

in',order to understand the contrast presented by Courbek's<br />

pavilion, at the very entrance to that Exposition;<br />

it I,fulfilled the carnivalesque function of deflating the<br />

pretentiousness of the mighty. And his gesture was<br />

indeed understood: Le Figaro described <strong>Courbet's</strong> pavilion,<br />

facing the Palais des Beaux-Arts of the Universal<br />

Exposition, as "Guignol's theatre next to La Scala of<br />

M lan ..z9 , ts, carnival floats into insurrectionary wagons<br />

poleon III had certainly not forgotten and his 1855<br />

iversal Exposition, far from having a carnivalesque<br />

that is, the Punch and Judy show, a satirical<br />

and subversive institution of popular culture, juxtaposed<br />

to! its antithesis, the high art opera house.

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM<br />

Ever since Meyer Shapiro's brilliant article of 1941<br />

"<strong>Courbet's</strong> Popular Imagery" 30, we have been aware of<br />

the relationship between <strong>Courbet's</strong> art and popular images.<br />

I would like to take that a step further and propose<br />

that <strong>Courbet's</strong> interest was not just in a generalized<br />

popular culture of Epinal prints and the customs of the<br />

rural bourgeoisie, but, with his instinct for the "most<br />

complete expression of a real thing" 31, Courbet focused<br />

on the most subversive and threatening aspect of popular<br />

culture, the only one that had both political overtones<br />

and a revolutionary history, namely carnival.<br />

The political carnivalesque informs <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855<br />

show. When Courbet wrote that his show "will really<br />

be enough to make Paris dance on its head", his statement<br />

conflated the two major features of carnival, revelry<br />

(fig. 5) with the image of the world-upside-down<br />

(fig. 6). The fear which Champfleury described as the<br />

conservative response to <strong>Courbet's</strong> show ("It's a scandal,<br />

it's anarchy, it's art dragged through the mud, it's<br />

a fairground spectacle") 32 was identical to their fear of<br />

carnival when all social order was transgressed. Taxile<br />

Delord, in Le Charivari described Courbet as a carnival<br />

barker shouting to artists to follow his example and<br />

abandon official expositions; 33 Gavarni drew just such<br />

an image of this popular carnival type as the introductory<br />

plate of "Les Debardeurs" (fig. 7).<br />

Daniel Stern (Marie d'Agoult) published an account<br />

of the invasion of the Tuileries in February 1848 which<br />

gives the flavor of Carnival/Revolution where<br />

masquerade and parody combine. Daumier's cartoon of<br />

the Paris gamin on the throne (fig. 8) is based on this<br />

incident. She wrote: "The children dress themselves up<br />

in velvet robes, turn the golden drapery fringe into belts,<br />

and pieces of tapestry into phrygian caps. The women<br />

pour over their hair the perfume that they find on the<br />

princesses' tables. They rouge their cheeks, cover their<br />

shoulders with lace and furs, decorate their heads with<br />

sprays of jewels and flowers; they deck themselves out<br />

with a kind of burlesque taste parodying extravagant<br />

dress" 34 . Compare this to <strong>Courbet's</strong> Young Ladies of the<br />

Village (fig. 9), criticized by Du Pays in L'/llustration<br />

as "the most anti-picturesque, the most unpleasant thing<br />

in the world: the pretention to elegance flaunted by the<br />

common people"35 . Even in conservative critics'<br />

frequent attacks on Courbet as the "apostle of ugliness",<br />

one can read the world-upside-down, for ugliness was<br />

the reversal of beauty, which to conservatives was the<br />

proper sphere of art.<br />

I am proposing that, if we look at Courbet in the<br />

light of carnival, we can better understand the hysteria<br />

his works provoked in conservative circles. Parody and<br />

26 1<br />

inversion assume a new and sinister dimension in the<br />

raucus Return from the Conference (fig. 10) featuring<br />

drunken priests, or the oversized Beggar's Alms<br />

(fig. 11) which the critic Chesneau claimed represented<br />

France 36 . Courbet constantly reversed the traditional<br />

hierarchical relationship of pictorial category to size: in<br />

paintings such as fhe Stonebreakers, The Grain Sifters,<br />

After Dinner at Ornans, ordinary people are elevated<br />

to a size and status traditionally reserved for gods and<br />

heroes. Parody nd inversion proved more subtle,<br />

though equally disturbing, in A Burial at Ornans<br />

(fig. 12), whose 'enter is the void of death, and whose<br />

red-nosed beadles seem to mock the solemnity of the<br />

event. In the light of Klaus Herding's reading of The<br />

Artist's Studio (fi 13) as an adhortatio ad principem,<br />

the traditional exportation to the ruler, Linda Nochlin<br />

has recently suggested that we might also read this as<br />

world-upside-do n, with the "normal" order of the<br />

world reversed: t~e monarch must now listen and learn,<br />

while the artist & ants the benefit of his example to the<br />

ruler 37 .<br />

FIG. 11. - Gusta~e COURBET. L'Aumone d'un mendiant d<br />

Ornans, 1868. Buprell Collection, Glasgow Museums and Art<br />

Galleries.

262 GAZETTE DES BEAUX-A(ZTS<br />

FIG. 12. - Gustave COURBET. Un Enterrement d Orn4ns, 1849. Paris, Music d'Orsay.<br />

Carnival existed at mid-century as a constellation of that carnival still contained. He created works which,<br />

attitudes and modes of behaviour; Courbet knew just like time bombs, would explode in politically and aeshow<br />

to exploit, under the guise of humor, the threat theticalllY conservative circles.<br />

FIG. 13. - Gustave COURBET, L'Atelier du peintre, alligorie rielle diterm'linant une phase de sept annies de ma vie artistique,<br />

1855. Paris, Muscle d'O0say.<br />

Fr<br />

fry<br />

N<br />

C<br />

O<br />

C<br />

1<br />

1<br />

1

FIG. 1 4. - C. THURSTON THOMPSON. "Fireman's Station and Division Wall be ween the Picture Gallery and Sugar Refinery",<br />

from R.J. Bingham and C.T. Thompson, Paris Exhibition, 1855, Tome I, No. XXXVIII. By Courtesy of the Board of Trustees<br />

of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.<br />

To his conservative audience, <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 show<br />

was certainly an exhibition. He travestied every aspect<br />

of high art practice, ostentatiously and immodestly, and<br />

did so with publicly avowed commercial intent. His<br />

contemporaries saw Courbet the carnival barker presiding<br />

over a disturbing vision of the world-upside-down,<br />

parodying the high, the mighty and the respectable; at<br />

the same time, they saw the spectre he presented of the<br />

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM<br />

future of art'', in the capitalist commodity system. For to<br />

true nineteenth century conservatives, the coming of the<br />

new bourgeois economic and social order was the<br />

world -ups id -down. What looks like a contradiction to<br />

us today was, in fact, a single nightmare vision in 1855,<br />

the defiant 11ero and the entrepreneur.<br />

P.M.

264<br />

This research was supported in part by a grant from T e<br />

City University of New York PSC-CUNY Research Award Pr~<br />

gram. An earlier version was read at the Symposium "Courbet<br />

Reconsidered", held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1988 in connection<br />

with the exhibition of the same title.<br />

I would like to express my gratitude to the photography<br />

historian Glenn Willumson who first discovered the photograph<br />

of <strong>Courbet's</strong> 1855 pavilion and made a copy print Of<br />

it available to me, to the historian Ann Ilan-Alter who is culrrently<br />

working on a study of carnival and without whose<br />

generosity I would not have been able to develop these i deaIIP~' ,<br />

and to Bernard Silve and Charles Daudon who helped with<br />

the transcription of the contract for <strong>Courbet's</strong> pavilion.<br />

1. Courbet to Alfred Bruyas, n.d., No. 10 in Courbet letters<br />

at the Biblioth6que nationale, Yb3 1739 (8), published n<br />

"Lettres inddites" L'Olivier, Revue de Nice, 8 (septembre-o -<br />

tobre 1913), 485-90. "Je vois ddjA d'ici tine tente 6norme av c<br />

tine settle colonne au milieu, pour murailles des charpent s<br />

recouvertes de toiles peintrs, le tout month stir tine estrad .<br />

Puis des municipaux de louage, tin homme en habit noir tena t<br />

le bureau, vis-'A-vis les Cannes et parapluies, puis deux ou tro s<br />

gargons de salle... 11 y a vraiment de quoi faire danser Par S<br />

Stir la tete, ce sera sans contredit la plus forte com6die q~i<br />

aura de jouer de notre temps; it y a des gens qui en tombero6t<br />

malades, c'est stir".<br />

2. See Patricia MAINARDI, Art and Politics of the Second<br />

Empire. The Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867, New<br />

Haven/London, 1987, 92-94.<br />

3. Augustin-Joseph Du PAYS, "Beaux-Arts. Expositi n<br />

Universelle", L'Illustration, 28 juillet 1855; QUILLENBOIS, " a<br />

Peinture rdaliste de M. Courbet", L'Illustration, 21 juill t<br />

1855.<br />

4. CHAMPFLEURY (Jules Husson), "Du R6alisme, Lettre ii<br />

Madame Sand", L'Artiste, 2 septembre 1855, 2-5 : "tine audace<br />

incroyable".<br />

5. This classic defense of the Salon of the Ancien R6gi e<br />

was formulated by L6on de LABORDE in his L'Application d s<br />

arts d l'industrie, Vol. 8 of the Commission frangaise stir I'i -<br />

dustrie des nations, Londres, 1851, Travaux de la Commissi<br />

frangaise stir I'industrie des nations, 8 vols., Paris, 1856,<br />

224-25.<br />

6. See "Exhibition", and "Exposition", in Paul ROBERt,<br />

Dictionnaire alphabetique et analogique de la langue frangaise,<br />

Paris, 1955, s.v.; Centre National de la Recherche Scie<br />

tifique, Tresor de la langue frangaise. Dictionnaire de<br />

langue du XIX ` et du XX` siecle (1789-1960), Paris, 198<br />

s.v.; Ferdinand BRUNOT, Histoire de la langue frangaise, 193<br />

S.V.<br />

7. See Koenraad A. SwART, The Sense of Decadence i<br />

Nineteenth Century France, The Hague, 1964, 55-56.<br />

8. Gustave COURBET, Exhibition et vente de 40 tablea x<br />

et 4 dessins de l'o'uvre de M. Gustave Courbet, avenue Mot<br />

taigne, 7, Champs-Elysdes, Paris, 1855.<br />

GAZETTE OES BEAUX-ARTS<br />

NOTES<br />

9. L6on ROSENTHAL pointed this out in his Du Romantisme<br />

au realisme, Paris, 1987, 3f, 37ff, 60; published 1914. Later<br />

Academicians whose writing illustrates these attitudes include<br />

Charles BEULt, "Du Principe des expositions", Causeries stir<br />

Part, Paris, 1867, and Georges LAFENESTRE, "Le Salon et ses<br />

vicissitudes", Revue des Deux Mondes 45 (1 mai 1881) : 104-<br />

35.<br />

10. Jean-Louis FoUCHt, "L'Opinion d'Ingres stir le Salon",<br />

La Chronique des arts et de la curiosite, 14 mars 1908, 99.<br />

"L'exposition nest plus qu'un bazar o6 la mddiocrit6 s'6tale<br />

avec impudence".<br />

11. E.J. DELECLUZE, Louis David, son ecole et son temps,<br />

ed. Jean-Pierre Mouilleseaux, Paris, 1983, 325; published<br />

1855. "Les salons du Louvre ont pris d'annde en ann6e le<br />

caractdre d'un bazar, oit chaque marchand s'efforce de pr6senter<br />

les objets les plus vari6s et les plus bizarres, pour provoquer<br />

et satisfaire les fantaisies des chalands".<br />

12. Jacques-Louis DAvID, Le tableau des Sabines, expose<br />

publiquement au palais national des sciences et des arts, salle<br />

de la ci-devant academie d'architecture par le citoyen David,<br />

Paris, an VIII (1799), 2; Deloyne 591, Vol. XXI : 631-648.<br />

MM.JouY et JAY, Salon d'Horace Vernet. Analyse historique<br />

et pittoresque de quarante-cinq tableaux exposes chez lui en<br />

1822, Paris, 1822.<br />

13. Several letters to Alfred Bruyas in 1854 and early 1855<br />

raise the question of a private exhibition; see COURBET,<br />

L'Olivier (cited n. 1).<br />

14. Georges RIAT, Gustave Courbet, peintre, Paris, 1906,<br />

82. T.J. CLARK in his Image of the People. Gustave Courbet<br />

and the Second French Republic 1848-1851, Greenwich, CT,<br />

1973, 85, states that Courbet held his Dijon exhibition in the<br />

caf6 but cites no source.<br />

15. RIAT, Ibid., 82. This seems to be a letter from Courbet<br />

to his friend Francis Wey, but Riat's text is unclear as to<br />

whether this was a written, spoken or fictionalized account.<br />

"ce qui prouve 6videmment que le grand ceeur, c'est de la<br />

niaiserie, par le fait que vous vous privez de moyens d'action<br />

sans enrichir les autres, ni par Fesprit, ni par la bourse. Afin<br />

d'etre libre, I'homme veut payer, que son jugement ne soit<br />

pas influenc6 par Ia.reconnaissance; it a raison. J'ai envie de<br />

m'instruire, et pour cela, je serai si brutal que je donnerai 3<br />

chacun la force de me dire les vdritds les plus cruelles".<br />

16. For a detailed discussion, see Patricia MAINARDI, "The<br />

Eviction of the Salon from the Louvre", Gazette des Beaux-<br />

Arts, juillet-ao0t 1988, 31-40.<br />

17. Jean-Louis FoucHt, "L'Opinion d'Ingres stir le Salon.<br />

Proc6s-verbaux de la commission permanente des Beaux-Arts<br />

(1848-1849)", La Chronique des arts et de la curiosite, 14<br />

mars 1908, 98-99. "Pour rem6dier A ce d6bordement des m6diocrit6s<br />

qui fait qu'il n'y a plus d'Ecole; 3 cette banalit6 qui<br />

est tin malheur public, qui afflige le gout, qui accable 1'administration<br />

dont elle absorbe les ressources sans rdsultat, it<br />

faudrait renoncer aux expositions...".

18. Louis PEISSE, "Le Salon de 1843", Revue des Deux-<br />

Mondes, n.s. 2 (1843) : 104. "Hors du Louvre, il n'y aurait<br />

plus de salon; il n'y aurait que des boutiques de tableaux".<br />

19. See Nicholas GREEN, "Circuits of production, Circuits<br />

of Consumption: The Case of Mid-Nineteenth Century<br />

French Art Dealing", Art Journal, Spring 1989, 29-34, and<br />

Linda WHITELEY, "Art et commerce d'art en France avant<br />

1'epoque impressioniste", Romantisme 4, (1983): 65-75.<br />

20. Courbet to Bruyas, letter No. 7, n.d., in the BN collection<br />

and L'Olivier (cited n. 1), 478-79; "Je grnene<br />

100 000 francs d'un seul coup". Courbet to Bruyas, n.d., in<br />

L'Olivier, 479-80; "Je vais passer pour un monstre mais je<br />

gagnerai 100 000 francs, d'apr6s toute prdvision". In an earlier<br />

letter to Bruyas, n.d., No. 10 in the BN collection, Courbet<br />

projects only 40,000 francs profit; see L'Olivier, 478-79.<br />

21. Courbet to Bruyas, n.d., in L'Olivier (cited n. 1), 479-80.<br />

22. David (cited n. 12), 2. "De nos joues, cette pratique<br />

est observde en Angleterre, oil elle est appelde exhibition".<br />

23. DELtCLUZE (cited n. 11), 212-213. "Le mode d'exposition<br />

adopte par David parut une innovation bien plus extraordinaire<br />

que l'idde de prdsenter ses personnages nus. L'artiste,<br />

a~-ant entendu parler des exhibitions telles qu'elles se pratiquent<br />

en Angleterre, c'est-3-dire en faisant payer un prix<br />

d'entrde a la porte, rdsolut de faire 1'essai de cette mdthode<br />

en France. Il ne fallut riens moins que la grande cdldbritd dont<br />

jouissait David et la curiositd extreme que faisait naitre son<br />

ouvrage, pour que I'on se conformat 3 un usage qui rdpugne<br />

a toutes les habitudes frangaises. Bien que I'on se soumit A<br />

cc mode d'exposition, puis qu'il rapporta vingt mille francs,<br />

on le blama gdndralement, et depuis, aucun artiste n'a osd y<br />

recourir de nouveau ".<br />

24. See MAINARDI, (cited n. 2), 44-46, 116.<br />

25. A.J. Du PAYS wrote that RtALISME, in large letters,<br />

,A-as written across the doors, but it cannot be seen in the photograph;<br />

see Du PAYS (cited n. 3), 72.<br />

26. Charles PERRIER, "Du Rdalisme, Lettre a M. le Directeur<br />

de 1'Artiste", L'Artiste, 14 octobre 1855, 86. "Tous le<br />

monde a vu, placardde aux murs de Paris en compagnie des<br />

saltimbanques et de tous les marchands d'orvidtan et dcrite<br />

en caracteres gigantesques, l'affiche de M. Courbet, apotre<br />

du rdalisme, i nvitant le public a aller ddposer la somme de<br />

un franc A Pexhibition de quarante tableaux de son muvre".<br />

27. Ernest GEBAOER, Les Beaux-Arts d 1'Exposition Universelle<br />

de 1855, Paris, 1855, 133. "M. Courbet, non content<br />

Tavoir eu onze tableaux admis A dExposition universelle,<br />

s'est passd la fantaisie d'une exhibition spdciale, A deux pas<br />

du palais des Beaux-Arts".<br />

28. For carnival during this period, see Alain FAURE, Paris<br />

Carente-prenant. Du carnaval d Paris au XlX e siecle 1800-<br />

COURBET'S EXHIBITIONISM 26 5<br />

1914, Paris, 1978; the February 1848 Revolution is discussed<br />

114-21. The basic work on carnival remains M.M. BAKHTIN,<br />

Rabelais and his World, trans. H. Iswolsky, Cambridge, MA,<br />

1968.<br />

29. Ajuguste VILLEMOT, "Chronique parisien", Le Figaro,<br />

8 juillet k855, 2. "Le thdatre de Guignol a c6td de la Scala<br />

de Milan'.<br />

30. Meyer SCHAPIRO, "Courbet and Popular Imagery", in<br />

his Modern Art. 19th and 20th Centuries. Selected Papers,<br />

New Yore , ',<br />

1978, 47-85. -<br />

31. See COURBET's letter to a group of students, Paris,<br />

25 d6cernbre 1861; published in Le Courrier du dimanche, 29<br />

ddcembr 1861, reprinted in Courbet raconte par lui-meme et<br />

par ses mis, Geneva, 1950, Vol. 2: 204-7. "L'imagination<br />

dans Fart consiste A savoir trouver Pexpression la plus<br />

complete ',1d'une chose existante, mais jamais e supposer ou 3<br />

crder cette chose meme".<br />

32. CHAMPFLEURY (cited n. 4), I.<br />

33. T~xile DELORD, "Exposition des Beaux-Arts. IV. L'annexe<br />

Co rbet", Le Charivari, 4 juillet 1855.<br />

34. Daniel STERN (Marie d'Agoult), Histoire de la Revolution<br />

de~1848, Paris, 1850, vol. I: 140-41. "Les enfants se<br />

revetent e robes de chambre en velours, se font des ceintures<br />

avec des Ifranges d'or et des torsades de rideaux, des bonnets<br />

phrygien$ avec des morceaux de tentures. Les femmes font<br />

ruisseler dans leurs cheveux les essences parfumdes qu'elles<br />

trouvent ~ur les tables des princesses. Elles fardent leurs joues,<br />

couvrent I leurs dpaules de dentelles et de fourrures, ornent<br />

leurs tet s d'aigrettes, de bijoux et de fleurs; elles se composent<br />

a , ec un certain gout burlesque des parures extravagantes".<br />

35. J. Du PAYS (cited n. 3), 72; on this painting, see<br />

Patricia AINARDI, "Gustave <strong>Courbet's</strong> Second Scandal : Les<br />

Demoise les de Village", Arts Magazine 53 (January 1979)<br />

95-109 : "c'est-a-dire ce qu'il y a de plus anti-pittoresque, de<br />

plus ddp aisant au monde : les prdtentions de 1'dldgance affichdes<br />

ar les lourdaudes".<br />

36. rnest CHESNEAU, "Salon de 1868", Le Constitutionnel,<br />

16 j in 1868. tmile Zola also commented on <strong>Courbet's</strong><br />

"bad joke" in this painting in his "Salon de 1868"; see $mile<br />

ZOLA, Salons, F.W.J. Hemmings, Robert J Niess, eds.,<br />

Geneva /Paris, 1959, 136-37.<br />

37. inda NOCHLIN, "CourbetIs Real Allegory: Rereading<br />

'The Pai ter's Studio"', in Sarah FAUNCE and Linda NOCHLIN,<br />

Courbet I Reconsidered, The Brooklyn Museum, New York,<br />

1988, 1 7 -41; Klaus HERDING, "Das Atelier des Malers -<br />

Treffpun t der Welt and Ort der Versohnung", Realismus als<br />

Widerspruch: Die Wirklichkeit in Courbets Malerei, Klaus<br />

Herding,', ed., Frankfurt-am-Main, 223-47.