Kru revisited, Kru revealed Lynell Marchese Zogbo ... - Llacan

Kru revisited, Kru revealed Lynell Marchese Zogbo ... - Llacan

Kru revisited, Kru revealed Lynell Marchese Zogbo ... - Llacan

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Kru</strong> <strong>revisited</strong>, <strong>Kru</strong> <strong>revealed</strong><br />

<strong>Lynell</strong> <strong>Marchese</strong> <strong>Zogbo</strong><br />

Welcome to the KRU (“crew”) language family<br />

• Very small under 12 million speakers<br />

• Limited to Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, with <strong>Kru</strong><br />

settlements Freetown Ghana<br />

• Past documentation rare (Koelle 1800’s,<br />

Delafosse 1904, Thomann 1906)<br />

• Dense forest, no kings, no classes, no masks (at 1 pt)!<br />

endangered? <strong>Kru</strong>s learn other langs, not reverse<br />

• Recent surge in research from late 60’s til present:<br />

-published grammars: Thomann, Innes, G. <strong>Zogbo</strong>;<br />

-doctoral dissertations: Kokora, Grah, Egner, G. <strong>Zogbo</strong>,<br />

Saunders, <strong>Marchese</strong>, Thalmann;<br />

-UQAM group: Kaye, Koopman, et al.;<br />

-SIL research: Bentinck, Leidenfrost, etc.<br />

-ILA theses and publications<br />

-<strong>Kru</strong> Atlas 1979 and Tense/Aspect and the development of auxiliaries in <strong>Kru</strong> (1979)<br />

• standard Niger-Congo features: noun class remnants, verbal extensions, a *CVCV word<br />

structure, labio-velars and at least one implosive stop, ATR vowel harmony, nasalized<br />

vowels in one half of family, and three to four level tones, as well as common lexical roots<br />

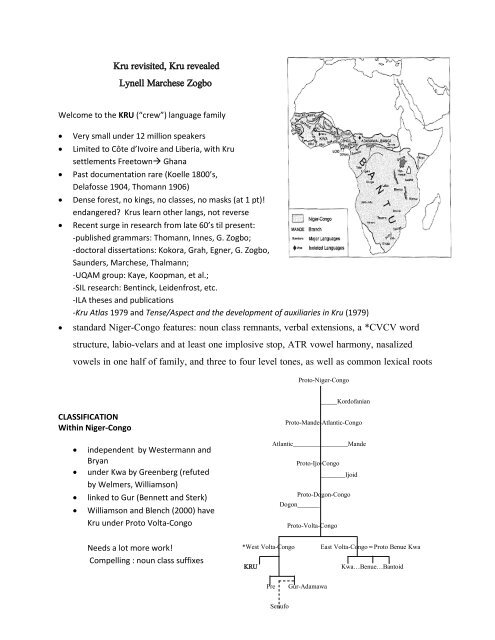

CLASSIFICATION<br />

Within Niger-Congo<br />

• independent by Westermann and<br />

Bryan<br />

• under Kwa by Greenberg (refuted<br />

by Welmers, Williamson)<br />

• linked to Gur (Bennett and Sterk)<br />

• Williamson and Blench (2000) have<br />

<strong>Kru</strong> under Proto Volta-Congo<br />

Needs a lot more work!<br />

Compelling : noun class suffixes<br />

Proto-Niger-Congo<br />

________Kordofanian<br />

Proto-Mande-Atlantic-Congo<br />

Atlantic___________________________Mande<br />

Proto-Ijo-Congo<br />

____________Ijoid<br />

Proto-Dogon-Congo<br />

Dogon___________<br />

Proto-Volta-Congo<br />

*West Volta-Congo East Volta-Congo=Proto Benue Kwa<br />

KRU Kwa…Benue…Bantoid<br />

Pre Gur-Adamawa<br />

Senufo

Internal classification<br />

Delafosse (1904) proposed division into two groups, Bakwé and Bété, now called Western and Eastern,<br />

divided by Sassandra river: There are several isolates:<br />

• Kuwaa and Dewoin in Liberia (confirmed)<br />

• Aizi in Côte d’Ivoire (confirmed)<br />

• Sεmε in Burkina Faso (not confirmed)<br />

West-East division demonstrated by correspondences, isoglosses & phonological feature:nasalized V’s<br />

t : s PWK *tu PEK *su<br />

‘tree’ tū Nyabwa sū Neyo<br />

tū Wobé sū Godie<br />

tū Gueré sū Dida Y<br />

tūgbὲ Tepo sū Bete GU, Bete GB<br />

tū Klao sū Kouya<br />

tuū́ Bakwe<br />

cu Bassa *tu > cu.<br />

ɲ: ŋ PWK *ɲ PEK *ŋ<br />

‘name’ ɲlɩ́ Nyabwa ŋlɩ́ Bete (D)<br />

ɲɩńɩ́ Wobé ŋlɩ́ Dida (Y)<br />

ɲnɩ́ Guere ŋnɩ́ Kouyo<br />

ɲnέ Klao ŋlʉ H Godié<br />

ɲrɩ́ Bakwe

‘woman’ PWK *ɲ PEK *ŋ<br />

ɲnɔ́ Krahn (T) ŋlɔ́ Neyo<br />

ɲrʋgba Tepo ŋwlɔ́ Godie<br />

ɲnɔ́ Guere ŋlɔ́ Dida Y<br />

ɲnáákpʋ̄ Wobe ŋɔ́ Dida L<br />

ŋlɔ̄ Bete<br />

ŋwnɔ́ Kouya<br />

ŋlʋ́ʋ́ Bakwé<br />

Note that here Bakwe shows a Western form for ‘name’ and an Eastern one for ‘woman’.<br />

gb: gw<br />

‘dog PWK *gbe M PEK *gwɩ<br />

Nyabwa gbē Godie gwe-yi<br />

Wobe gbē Dida go-yi<br />

Guere gbē Bete GU gwɩ̄<br />

Tepo gbì Bete GB gwē<br />

Klao gbè Bete D gwɩ̄<br />

Bassa gbē Kouya gwɩ̄<br />

Bakwé and Neyo show fricatives for this lexical item. Neyo has vɩ or vɔ M and Bakwe, fɛ L.<br />

Numerous isoglosses:<br />

Western Eastern<br />

‘fire’ PWK *nε PEK *kosu<br />

Nyabwa nε̄ Neyo kòsù<br />

Wobé nε̄ Godie kòsú<br />

Guere nε̄ Dida (Y) kòsù<br />

Tepo nā Bete-G kòsù<br />

‘tooth’ PW *nynɩ H PKE *gle M<br />

Nyabwa ɲnɩ́ Neyo grē<br />

Wobé ɲnɩ́ /nynɩε Godie glē<br />

Guéré ɲnɩ́ɛ̀ Bete (GU) glē-yì<br />

Tepo ɲέε̄ Bete (GB) glε̄<br />

Klao ɲέ Bete (D) glē-yī<br />

Bassa ɲεńέ Kouya gla 1<br />

Bakwé glὲ<br />

Questions: Eastern Neyo? Dida? border languages Bakwé, Kouya ; Western subgroup Wè vs <strong>Kru</strong> ;<br />

1 This is the plural of gle in many languages.

PROTO-PHONOLOGY<br />

*CVCV-(C) V & probably *CVV ; current CLV and syncopated syllable types are derived<br />

*Four level tones, with a few examples of 4 > 3, innovated modulated tones resulting from toneconsonant<br />

interaction and consonant voicing; tone carries a high functional load in the lexicon and in<br />

the grammar: distinguishing 1-2 nd person (sg and pl), perfective-imperfective, negation<br />

egg<br />

Proto <strong>Kru</strong> Initial consonants (<strong>Marchese</strong> unpublished, 1976) current analysis<br />

p b c g kp p t k kp<br />

b d ɟ k gb b d g gb<br />

m n ɲ ng ɓ l w<br />

s m n ? ?<br />

z w s<br />

kw, gw derived from CVV c, j, ny derived? g > ɟ gie> ɟ ie<br />

l realized as flap l, r, n, ɗ ???relationship bt l-d-ɗ,<br />

c, s > h in several <strong>Kru</strong> languages *y<br />

k > f, s > z z, s > f v? g > gh group of Bete<br />

*ɓ Ny Wob Guer Tep Bass Bakw Kouy BeD BeG Godi Ney De<br />

Leg ɓʋ̄ ɓʋ̄ ɓʋ̄ ɓʋ̀ ɓo bɔ̄ʋ́ ɓʋ̄ ɓʋ2 ɓō ɓɔ̀ɔ́ ɓō<br />

Two stages Proto <strong>Kru</strong> I (oldest ) and Proto <strong>Kru</strong> II<br />

Proto-<strong>Kru</strong> II ‘bush’ kwálá or kwlá < Proto <strong>Kru</strong> I **kʋlá<br />

‘moon’ *cʋ h < Proto <strong>Kru</strong> I **kí-ʋ (Kuwaa: kewu)<br />

‘dew’ *ɟ lù < Proto <strong>Kru</strong> I **dilù<br />

‘breast *ɲiti < Proto <strong>Kru</strong> I ?<br />

n…………………………..ng(w) ………………… …w<br />

‘mouth’ nё, ne Godie, Neyo ngwε Kouya, wɔn Klao, Bassa<br />

ngo Bete D wɩ Tepo<strong>Kru</strong>men<br />

nguo Wobe, Guere wɔɩ Dewoin<br />

‘hear’ nú Neyo, Godie, Dida ngwɔ Grebo wɔn Tepo, Klao, Bassa<br />

nʋ̄ Bete, Kouya<br />

CompareWilliamson and Bench (2000:41)<br />

*Western Sudan Kordonfanian *Proto-<strong>Kru</strong><br />

#nu, ‘hear’ -eenu ‘ear’ *nú? ‘hear’

#nu, -nua ‘mouth’ *uungu *nV? ‘mouth’<br />

VOWELS<br />

Proto <strong>Kru</strong> oral vowels PWK Nasalized<br />

ɩ ʋ ɩn ʋn<br />

e o<br />

ε ɔ εn ɔn<br />

a an<br />

*vowel harmony everywhere: retracted but some +height<br />

*predictable nasalization after nasal C or N dropping<br />

*divide: nasalized Vs in West, almost none in East; all nasalized V’s except e & o<br />

Western (nasalized vowels)<br />

Nyabwa Wobe Guere Klao Bassa<br />

Tail gʋn M gʋn M gʋn M wɔn M vɔn M<br />

Arm sʋn M sʋn M sʋn M sɔn M<br />

Two sɔn H sɔn H sɔn H sɔn H sɔn H<br />

Eastern (oral vowels)<br />

Neyo Godie Dida BeteGGB Koouya<br />

tail gʋ go M go M go-yì<br />

Arm sɔ sɔ sɔ sɔ<br />

Two sɔ H sɔ H mɔsɔ BH sɔ sɔ H<br />

Complementary distribution in Western <strong>Kru</strong><br />

Klao (Singler): voiced stops and oral Vs /dan/ [nan] MH ‘drink’ vs /da/ ‘call’MH, never<br />

[dan], never [ma], but distinction with voiceless stops: pi ‘cook’ pin M ‘load (on head)’<br />

Did Proto-<strong>Kru</strong> have nasalized V’s or not? If so, what triggered de-nasalization in Eastern <strong>Kru</strong>?<br />

Positing proto nasalized vowels and no nasal consonants (Le Saout, Bole-Richard, Vydrine for<br />

Mande) doesn’t work for East <strong>Kru</strong>. Could <strong>Kru</strong> have borrowed nasalized vowels from Mande??<br />

Central vowels : innovated in Eastern <strong>Kru</strong> (Bete, Godie) but not in Dida and Neyo:<br />

i ï U<br />

ɩ ʉ ʋ<br />

e ə O<br />

ɛ ʌ ɔ<br />

a<br />

Bakwé has central vowels, is it genetic or areal? Why this innovation? SMande=central V’s<br />

Note weird fact: where central vowels occur, there are no nasalized Vs!!!

PROTO-MORPHO-SYNTAX<br />

TAM<br />

• Currently SVO, but much OV typology:<br />

-ɔ lï sʉkʌ (SVO) ɔ yi sʉkʌ lï (S AUX O V)<br />

‘he eats rice’ ‘he will eat rice’<br />

-GEN N with or without associative*a (alienable/inalienable)Nyabwa gbe á kpá bone of dog<br />

-N Postposition<br />

-OV noun compounding<br />

• <strong>Kru</strong> is 100% suffixing: plurals in nouns & verbs (extensions: applic, passive, valency)<br />

• No serial verbs but conjoined propositions with AUX sequential from ‘come’<br />

• Comparison: expressed by *proto ‘pass’ construction: *X is good pass Y<br />

• Topic-comment style with front shifted focus, affirmative focus particles within clause<br />

Aspect dominates: perfective and imperfective reconstructed for Proto <strong>Kru</strong> with perfective<br />

basically an unmarked verb stem (but there is a pervasive low tone throughout the family).<br />

Proto imperfective is the marked form, reconstructing to *NP a V-e (<strong>Marchese</strong>, 1982)<br />

Which is older? Both persist. In some languages a has suffixed onto NP, producing an<br />

imperfective pronoun set. In others a is lost. In many languages –e reduces to mid tone. Did<br />

low perfective tone marking innovate to provide a clear distinction (dissimilation)? Did a proto<br />

tense marker get re-analyzed, then reduce to low tone (contra expectation tense > aspect)?<br />

There is a proto periphrastic progressive * he is-at bathe-place ‘he is bathing’.<br />

Tense is secondary. Some evidence of recent and remote past tense suffixes: #a or #i ‘recent’<br />

(Godie, Dewoin) and #o/wo, wʌ (remote). But extensive tense innovation derived from temporal<br />

adverbs most extensively in the <strong>Kru</strong> cluster (Klao, Cedepo, TepoKroumen, Bassa, etc). (See<br />

<strong>Marchese</strong>, 1984). The innovative tenses range from 1 to 5, highest in Grebo (Innes, 1969):<br />

(i) né dú blà. ʻI pounded rice ʼ.<br />

I pound rice<br />

(ii) né dú-da blà. ʻ I pounded rice the day before yesterday ʼ.<br />

(iii) né dú-d́ blà. ʻI pounded rice yesterday. ʼ<br />

(iv) né dú- blà. ʻ I pounded rice today.ʼ<br />

(v) né dú-a blà. ʻ I will pound rice tomorrow.ʼ<br />

(vi) né dú-d blà ʻI will pound rice the day after tomorrow. ʼ<br />

Auxiliaries express future, potential, perfect, sequential, negation, relatively recent development<br />

and currently on-going : SV (O)V-nom S AUX (O) V, (1986)

‘come’ future, sequential, potential; ‘have’ future, conditional, ‘bring’? .perfective,<br />

‘stop’, let go’ NEG markers. True reanalysis : Aux: no perf-imperf, take obj & tense suffixes<br />

NOUN CLASSES and AGREEMENT<br />

Proto <strong>Kru</strong> words were made up of *STEM + Class suffix<br />

Vestiges seen in:<br />

Pronouns:<br />

• Pronoun systems 3 rd person<br />

• Singular + plural forms : regular and irregular<br />

• In some languages, in definite markers<br />

• Remnants of concord<br />

Primary distinction is human vs non human:<br />

3 rd singular with hierarchy human > big animals > everything else<br />

Human Non-human<br />

Kuwaa (isolate) ɔ ɛ̄<br />

Niaboua (Wè) ɔ̄ ɛ̄<br />

Wobé (Wè) ɔ̄ ɛ̄<br />

Grebo (<strong>Kru</strong> cluster, W) ɔ ɛ<br />

Djabo ɔ ɛ<br />

Kouya (East) ɔ we<br />

Tepo <strong>Kru</strong> (<strong>Kru</strong> cluster, W) ɔ ɛ, o, ɔ<br />

Neyo (E) ɔ ɛ, a, ʋ<br />

Godié (E) ɔ̄ ɛ, a, ʋ<br />

Bété (Daloa) (E) ɔ́ ɛ, a, ʋ 2<br />

Dida (Yocoboué)<br />

ɔ ɛ, a, ʋ<br />

On the basis of these pronouns, we posit for 3 rd singular human *ɔ and three non-human classes<br />

*ɛ, *a, *ʋ. In many cases there are clear semantic categories which link to class markers and or<br />

remnants in other families. Currently, however, this system is described phonologically by all<br />

(Grah, Kaye, <strong>Marchese</strong>, Sauder, Saunders, Thalmann, Werle, <strong>Zogbo</strong>): in Eastern <strong>Kru</strong>, NHum<br />

words ending in front V’s take ɛ, central Vs, a, back Vs, ʋ, but final V reflects old noun class<br />

marker.<br />

In Godié nouns ending in front vowels belong to the *ɛ big animal class (many taking –a in the<br />

plural):<br />

mlɛ “animal” Ɉɛ “antilope<br />

lʋɛ “elephant” glɛ “monky” (SP)

kaɓɛ “monkey”(SP) tlɛ “snake”<br />

gbalɛ “hippopotamus” bɔlɛ “monkey”<br />

ɓlɛ “buffalo” gwɛ “chimpanzee”<br />

ɓaɓlɛ “sheep” ɓlɛ “antelope”<br />

kpəkɛ “crocodile” Ɉɩ “panther”<br />

dʋdʋzʋɛ “anteater” ɓlɩ “cow”<br />

Compare other families for the word ‘goat’ 3:<br />

Yoruba e-wúrɛ́<br />

Efik e-bot<br />

Igbo e-wu<br />

Proto-bantu ɩN-boli<br />

Kordofanian e-bonyi<br />

<strong>Kru</strong> (Godié) wuli-ɛ (definite form)<br />

Godié nouns ending in back vowels take the *ʋ pronoun. Note liquids and mass.<br />

liquids non –solid masses<br />

ɲʋ́ “water” jlʋ̀ “fog”<br />

ɓlʋ “milk” vʋvɔlʋ “wind”<br />

dlʋ “blood” gbaylʋ “smoke”<br />

nʋ “alcoholic drink” ɓàɓʋ̀ “dust”<br />

zo “soup” nyɔmʋ “air”<br />

bubʋ “sweat” zùzʋ “spirit, shadow”<br />

natural elements miscellaneous (these take ɩ in plural)<br />

kòsu “fire” wlʋ́ “head”<br />

lagɔ “sky, God” lʋ “song”<br />

dʋdʋ “earth” blɔ “road”<br />

glʋ “soil” ylʋ “day”<br />

ylʋ “sun”<br />

cʋ “moon, month”<br />

Compare PB 3/4 mʋ/mi , PBenue-Congo ʋ/(ɩ)I, Togo Remnant *o/*i , the *o –prefix in Yoruba:<br />

omi “water” ɔna “road” ɔbɛ “soup” orin “ song”<br />

ɔrun “heaven” ošu “moon” ori “head”<br />

The a class is not so definable, but includes food, instruments, small insects, etc. Examples from Godie :<br />

sʉkʌ ‘rice’, nimlə ‘bird’, nyidə ‘cooking pot’; Bete (G): ɟá ‘wound’, mla ‘nose’, zɩa, ‘bird’.<br />

Reconstruction of noun stems is difficult because the noun class V suffix has ‘taken its spot’:

*ní +ʋ ɲú ‘water’ *lʋ-ε ‘elephant’ *yVlV- ʋ ‘sun’ nV + ʋ ‘alcoholic drink’<br />

Class concord or agreement is reflected across the family first and foremost in pronouns:<br />

subject, object, possessive, relative, interrogative, without overt reference in discourse.<br />

Within the NP, concord marks various elements, depending on the language:<br />

noun +adjective + demonstrative + number (definite floating)<br />

Godie ɓìtì kʌdɩ HL nɩ sɔ ‘those two big houses’<br />

Nyukpɔ kʌdɔ nɔ nii mlε kʌdε. Nykpɔɔ -ɔ nii mlε nʌ, ɔ kʋ ɔ ɓutu kádʋ<br />

‘man big DEM saw animal big Man-def REL saw animal SUB, he is-at his house big<br />

The big man saw a large animal’. . ‘The man who saw an animal is in his big house.<br />

Noun + Adjective + Demonstrative Noun + definite<br />

nyʉ̄kpɔ̄ kʌ́dɔ̄ nɔ̄ ‘this big (great) man’ nyʉ̄kpɔ̄ + ɔ LM ‘the man’<br />

ɓùtu kʌ̀dʋ nʋ ‘this big house’ li + ε lie ‘the spear’<br />

mlɛ̄ kʌ̍d̍ɛ̄ nɛ̄ ‘this big animal’ ɓùtù + ʋ ɓùtùu ‘the house’<br />

nmlə kʌ̍dʌ̄ nʌ̄ ‘this big bird’<br />

ɓı ̀tı̄ kʌ̍dɩ̄ nɩ̄ ‘these big houses’<br />

nyʉ̄kpà kʌ́dʋa nʋa ‘these big (great) men’<br />

The same agreement system exists in Bakwé, as seen in the following<br />

Noun + adjective ‘only’ 4<br />

nyɔɔ ˈdoolɔ le seul homme<br />

tatu ˈdoolʋ la seule porte<br />

sapɛ ˈdeelɛ le seul poulet<br />

ˈkpata ˈdöölä la seule chaise<br />

For adjectives, the situation varies greatly from language to language. Some agree with class and<br />

number as in Godie and Bakwe forms above, while some only agree in number. Where there is<br />

adjective class agreement, only a subset of adjectives agree, often the words ‘big’, ‘white’, ‘red’ and<br />

‘new’. As the class agreement diminishes, plural agreement can remain. But note that for Tchien<br />

Krahn, Sauder reports the qualified nouns take the non-human plural marker5. True everywhere<br />

nyɔ klàbá ‘an important person/ man’ (big) nyʋ klàbɩ ‘important people’<br />

dε zʋ n ‘bad thing’ dɩ zʋɩn ‘bad things’ nyʋ zʋɩn ‘bad people’<br />

Tepo <strong>Kru</strong>men6: ya ká yɩ kɩ ‘old pot/pots’<br />

hru pεtú hri pεti ‘short road/roads’<br />

yu yrayrʋ yuó yrayrɩ ‘new child/children<br />

4<br />

Examples from Csaba Leidenfrost.<br />

5<br />

Sauder, p. 46<br />

6<br />

Thalman. P. 251

The less the number of pronoun (class) distinctions, the less concord within the NP. The closer<br />

the element to the head noun, the more likelihood of agreement (no 1 st , dem/def 2 nd ). The loss<br />

of agreement in adj works its way through the lexicon, class marked colors & plurals resisting.<br />

Language Dem Adj1 Def Adj2 Num<br />

Godié X x/10 X x/4? 0<br />

Bété (Guibéroua) X X X X/? 0<br />

Neyo X X X X/? 0<br />

Wobe X X/10 NR x/1 0<br />

Kouya 0 X NR ? 0<br />

Grebo X S ? 0 0<br />

Kuwaa SG/PL X/1 X 0<br />

KLao 0 X 0 0 0<br />

Dewoin 0 ? 0 0 0<br />

X = agreement present<br />

0 = no agreement<br />

Adj 1 agree in number<br />

Adj 2 agree in class & number<br />

Definite seems innovative<br />

• The <strong>Kru</strong> system shows important links to human, large animal, and liquid-mass classes<br />

in other NC languages.<br />

• It ‘respects’ their “membership” even including what appears to be unusual members!<br />

• It suggests that proto NC might have had less than more (noun classes)!<br />

• The <strong>Kru</strong> system shows there are hierarchies of semantic categories in ‘reduction<br />

schemes’ with certain categories persisting: human over everything else, animate (?)<br />

over inanimate, big over little? Color over ?, Plural over class?<br />

• How and why do class and concord systems develop and why do they fade? Do any other<br />

NC language families show class agreement moving to phonological agreement?<br />

<strong>Marchese</strong>, L. (1979, 1983), <strong>Kru</strong> Atlas, Abidjan: ILA , 1979, 1983.<br />

______________ (1982) 'Basic Aspectual Categories in Proto-<strong>Kru</strong>' in JWAL, Vol. 12, No. 1. pp. 3-23.<br />

______ (1984) 'Exbraciation in the <strong>Kru</strong> language family', Historical Syntax, lacek Fisiak (ed.). Mouton, pp. 249-270<br />

______ (1984), 'Tense Innovation in the <strong>Kru</strong> language family', Studies in African Linguistics.<br />

Vol. 15 No. 2, UCLA.<br />

______ (1986) Tense/Aspect and the Development of Auxiliaries in the <strong>Kru</strong> Language Family, SIL-Universitiy of<br />

Texas Press, Arlington, 1986, 301 pages. (UCLA Phd thesis under Welmers and Thompson, 1979)<br />

-------(1988) 'Noun Classes and agreement systems in <strong>Kru</strong>: A Historical Approach', in Agreement in natural<br />

language: Approach, theories and descriptions. Barlow and Ferguson (eds.), Stanford University Press.<br />

______ (1989) '<strong>Kru</strong>', in The Niger-Congo Languages. 1. Bendor Samuel (ed.), Lanham: University Press of<br />

America, Inc. - SIL, pp. 119-13<br />

Thanks to Csaba Leidenfrost, Philip Saunders, Peter Thalmann, R. <strong>Zogbo</strong>, J. Blewoue & especially Hortense Tebili!

![[halshs-00645129, v1] Depressor consonants in Geji - Llacan - CNRS](https://img.yumpu.com/17832391/1/190x245/halshs-00645129-v1-depressor-consonants-in-geji-llacan-cnrs.jpg?quality=85)