2008SP - University of Utah

2008SP - University of Utah

2008SP - University of Utah

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

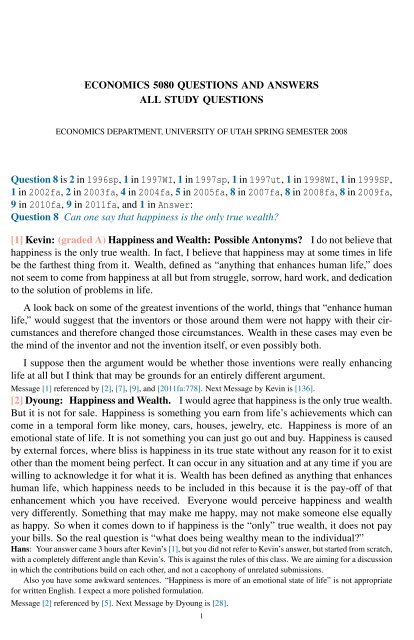

ECONOMICS 5080 QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS<br />

ALL STUDY QUESTIONS<br />

ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT, UNIVERSITY OF UTAH SPRING SEMESTER 2008<br />

Question 8 is 2 in 1996sp, 1 in 1997WI, 1 in 1997sp, 1 in 1997ut, 1 in 1998WI, 1 in 1999SP,<br />

1 in 2002fa, 2 in 2003fa, 4 in 2004fa, 5 in 2005fa, 8 in 2007fa, 8 in 2008fa, 8 in 2009fa,<br />

9 in 2010fa, 9 in 2011fa, and 1 in Answer:<br />

Question 8 Can one say that happiness is the only true wealth?<br />

[1] Kevin: (graded A) Happiness and Wealth: Possible Antonyms? I do not believe that<br />

happiness is the only true wealth. In fact, I believe that happiness may at some times in life<br />

be the farthest thing from it. Wealth, defined as “anything that enhances human life,” does<br />

not seem to come from happiness at all but from struggle, sorrow, hard work, and dedication<br />

to the solution <strong>of</strong> problems in life.<br />

A look back on some <strong>of</strong> the greatest inventions <strong>of</strong> the world, things that “enhance human<br />

life,” would suggest that the inventors or those around them were not happy with their circumstances<br />

and therefore changed those circumstances. Wealth in these cases may even be<br />

the mind <strong>of</strong> the inventor and not the invention itself, or even possibly both.<br />

I suppose then the argument would be whether those inventions were really enhancing<br />

life at all but I think that may be grounds for an entirely different argument.<br />

Message [1] referenced by [2], [7], [9], and [2011fa:778]. Next Message by Kevin is [136].<br />

[2] Dyoung: Happiness and Wealth. I would agree that happiness is the only true wealth.<br />

But it is not for sale. Happiness is something you earn from life’s achievements which can<br />

come in a temporal form like money, cars, houses, jewelry, etc. Happiness is more <strong>of</strong> an<br />

emotional state <strong>of</strong> life. It is not something you can just go out and buy. Happiness is caused<br />

by external forces, where bliss is happiness in its true state without any reason for it to exist<br />

other than the moment being perfect. It can occur in any situation and at any time if you are<br />

willing to acknowledge it for what it is. Wealth has been defined as anything that enhances<br />

human life, which happiness needs to be included in this because it is the pay-<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> that<br />

enhancement which you have received. Everyone would perceive happiness and wealth<br />

very differently. Something that may make me happy, may not make someone else equally<br />

as happy. So when it comes down to if happiness is the “only” true wealth, it does not pay<br />

your bills. So the real question is “what does being wealthy mean to the individual?”<br />

Hans: Your answer came 3 hours after Kevin’s [1], but you did not refer to Kevin’s answer, but started from scratch,<br />

with a completely different angle than Kevin’s. This is against the rules <strong>of</strong> this class. We are aiming for a discussion<br />

in which the contributions build on each other, and not a cacophony <strong>of</strong> unrelated submissions.<br />

Also you have some awkward sentences. “Happiness is more <strong>of</strong> an emotional state <strong>of</strong> life” is not appropriate<br />

for written English. I expect a more polished formulation.<br />

Message [2] referenced by [5]. Next Message by Dyoung is [28].<br />

1

2 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

[5] Hans: Why does nobody notice that logarithms can’t be yellow? The answer to<br />

this question has two parts, I will number them (1) and (2):<br />

(1) First <strong>of</strong> all, you cannot say anything intelligent about this question if you don’t notice<br />

that “happiness is the only kind <strong>of</strong> wealth” is a nonsensical statement. It is like saying<br />

“laughter is the only kind <strong>of</strong> joke.” Wealth is an input into the process <strong>of</strong> living, while<br />

happiness is an output from the process <strong>of</strong> living. I elaborated on this in [1999SP:12], which<br />

I recommend as reading. (In other words, if others contribute to this same question, I expect<br />

them to have read it.)<br />

(2) The above is only the first part <strong>of</strong> the answer, so-to-say the preliminary. The more<br />

interesting part comes now: why is it not obvious to everybody that this is a nonsensical<br />

statement? Now we go from logic to sociology.<br />

The submitted answers seemed always striking to me because people are so quick to<br />

denigrate wealth. I am a Marxist. I think we are living in a society in which there is a lot<br />

<strong>of</strong> blatant exploitation, but this exploitation is hidden from those being exploited. From this<br />

starting point it is easy to come to the conclusion that this denigration <strong>of</strong> wealth is part <strong>of</strong><br />

the defence mechanism which allows everybody not to see their exploitation. If wealth is<br />

irrelevant, if it is more important to have a good attitude than to have material resources as I<br />

just happened to read in [2005fa:120], then it is easier to live with the fact that all the wealth<br />

we are producing is stolen or misappropriated.<br />

But Dyoung’s answer [2] adds a different dimension to it. When Dyoung says happiness<br />

is not for sale, and it does not pay your bills – but wealth does – he seems to identify wealth<br />

with things that can be bought and sold. But purchases and sales are not wealth itself but<br />

they are the social form which wealth takes in our society. Therefore his suspicion about<br />

wealth is also a critique <strong>of</strong> the existing social relations.<br />

Can you be convinced that you are not critical <strong>of</strong> wealth itself but <strong>of</strong> the form wealth<br />

takes in our society? Let’s imagine components <strong>of</strong> wealth which cannot be bought or sold.<br />

By taking classes at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> you are enriching your lives – not only because<br />

you may get a better paying job afterwards but also because you know more about the world<br />

and about yourself. And the nice thing about this kind <strong>of</strong> wealth is: nobody can take it away<br />

from you.<br />

This takes me to another aspect in Dyoung’s answer, and in many answers before him.<br />

Wealth is seen as a reward for sacrifice. Again I think this is an implicit critique <strong>of</strong> our social<br />

relations, for two reasons – this time I call them (a) and (b):<br />

(a) Why should production, arguably the noblest activity humans can pursue, be considered<br />

a sacrifice? My Marxist knee-jerk answer here is: because in our society, production is<br />

bound up with exploitation. The disgusting part <strong>of</strong> our work lives is not the production part<br />

but the exploitation part.<br />

(b) Why should the incredible wealth in this society only be made available so some and<br />

not shared by everybody? If you answer: it is necessary as an incentive to produce more,<br />

then my Marxist knee-jerk answer is: We don’t need more production. More production as

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 3<br />

we know it from capitalism causes climate change and ruins the living conditions for humans<br />

on the planet.<br />

Message [5] referenced by [7], [8], [13], [14], [15], and [2008fa:18]. Next Message by Hans is [8].<br />

[7] Lev: Happiness and Wealth. Well, one could certainly say it but they wouldn’t<br />

necessarily be correct. ;-)<br />

Kevin suggested in [1] that the quest for wealth “does not seem to come from happiness<br />

at all but from struggle, sorrow, hard work, and dedication to the solution <strong>of</strong> problems in<br />

life”. It would seem however this to have the question the wrong way around. The question<br />

does not ask whether wealth provides happiness, but whether happiness is the only true<br />

wealth; the word order provides a question <strong>of</strong> significantly different quality. Hans [5] has<br />

indicated whether the question is pragmatically commensurable in the first place, but again I<br />

would point out that the question did not ask whether “happiness is the only kind <strong>of</strong> wealth”<br />

but rather it is the only true wealth; a statement itself which does fall into the “No True<br />

Scotsman” sort <strong>of</strong> fallacy).<br />

Nevertheless, many would intuitively agree with the proposition as the “quest for happiness”<br />

has been a dominant theme in intellectual thought and practical application for many<br />

years. In Plato’s “Crito”, the contemplative philosopher Socrates argues that the most important<br />

aim in a person’s life is to achieve happiness through virtuous knowledge <strong>of</strong> the good,<br />

achieved through self-development, and the cultivation <strong>of</strong> friendships <strong>of</strong> good people. It is<br />

not life, he argues, but a good life that is to chiefly valued (Crito, 48b). Aristotle, following<br />

a similar line <strong>of</strong> reasoning in the “Nichomachean Ethics”, developed a system <strong>of</strong> “virtue<br />

ethics”, arguing that the function <strong>of</strong> the human soul was to have a true life built on balanced<br />

consideration and action.<br />

It may seem surprising then that given the emphasis <strong>of</strong> the ancient Hellenes to good moral<br />

choices being the path to happiness, that some contemporary biopsychologists (e.g., Pr<strong>of</strong>.<br />

Kent Berridge, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michgan, Stefan Klein in The Science <strong>of</strong> Happiness (2006))<br />

argue that happiness is largely determined by neurochemical states, that is, the relative presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural opiates like dopamine in the brain. On a related approach some [1] have<br />

claimed that 50% <strong>of</strong> happiness is from genetic basis, and only 10-15% from socio-economic<br />

origins, although the particular study does suffer from selection bias.<br />

Countering this claim from the discipline mainstream economics and its utilitarian calculations.<br />

Some significant attempts have been made to differentiate between wealth as<br />

measured by GDP and life quality overall. These are interesting as they show exactly how<br />

far the definition <strong>of</strong> wealth in the political and economic system (as defined by exchange values)<br />

is from representing satisfaction (as defined as use values). In 2005, “The Economist”<br />

produced such a study. As one would obviously expect there was an positive correlation between<br />

GDP per capita and quality <strong>of</strong> life. However there were significant disparities between<br />

the two depending on how the GDP was used.<br />

The nations were the Quality <strong>of</strong> Life was significantly higher (10 ranks or more) than<br />

their GDP per capita in the larger economies included places like Sweden (+14), Italy (+15),<br />

Spain (+14) and New Zealand (+10). Places where the QoL index was significantly lower<br />

than their GDP per capita included the United States (-11), the United Kingdom (-16), Saudi

4 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

Arabia (-23), and almost at the bottom <strong>of</strong> the list (despite being a mid-range economy according<br />

to GDP per capita), was Russia (-50). The best places to live, overall, were Ireland,<br />

Switzerland, Norway, Luxembourg, Sweden, Australia, Iceland, Italy, Denmark and Spain,<br />

Singapore and Finland.<br />

Combining the various approaches it would seem necessary to differentiate [2] between<br />

“labour”, those unpleasant activites (as Kevin illustrated) necessary to provide the necessities<br />

<strong>of</strong> life, between “work”, the payment <strong>of</strong> activity for wages, subject to the various forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> exploitation, power relations etc and “action”, the free and conscious activity without<br />

restrains, an ideal found in Arendt and especially in Herbert Marcuse (cf., Eros and Civilization).<br />

Making this differentiation, and on the upper level <strong>of</strong> activity, would allow one to<br />

define “action” as happiness as not the only true wealth, but certaily the one which is the<br />

highest form, albeit only achievable under certain conditions.<br />

1] Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, Schkade in “Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture <strong>of</strong> Sustainable<br />

Change”, Review <strong>of</strong> General Psychology 2005, Vol. 9, No. 2, 111-131<br />

2] As Hannah Arendt did in her studies on the human condition and Engels made explicit<br />

in his speech at Marx’s graveside.<br />

Message [7] referenced by [15]. Next Message by Lev is [14].<br />

[9] Hans: Wealth without Misery? Kevin [1] does not try to answer the nonsensical<br />

question whether happiness is wealth, but switches to the more interesting question whether<br />

happiness is conducive to the production <strong>of</strong> wealth. His answer is “no,” and Marx would<br />

agree. Marx says in 648:2/oo: “Where nature is too lavish, she ‘keeps [humankind] in hand,<br />

like a child in leading-strings’.”<br />

Prior to capitalism, the highest level <strong>of</strong> technology was achieved by independent artisans<br />

and peasants producing for the market (petty commodity production). But these proud and<br />

independent producers would never have agreed to the discipline <strong>of</strong> large-scale direct cooperation.<br />

One might say they were too happy in their independence, they would never<br />

have dreamt <strong>of</strong> giving it up voluntarily. Only when they lost their independence and became<br />

wage laborers <strong>of</strong> the same capitalist, could they be forced to directly co-operate. Instead <strong>of</strong><br />

a human-based production process, capital introduced a modern science-based production<br />

process, a revolution which necessarily had to go against the will <strong>of</strong> the laborers themselves.<br />

The capitalists did this only in order to be able to exploit the workers better, but the historical<br />

gift which they unwittingly made is the enormous jump <strong>of</strong> productivity when individual<br />

production was replaced by massively co-operative production.<br />

What I just wrote is spelled out in various places in Capital, see e.g. 453:1, 775:1/o.<br />

Again we see that it was not happiness but the coercion associated with capitalist exploitation<br />

that lead to more wealth. Marx recognizes this as the historical mission <strong>of</strong> capitalism.<br />

He thinks capitalism is a phase humankind had to go through in order to develop labor<br />

productivity, but it has long outlived its usefulness and must be replaced now by a more<br />

participatory economic system.<br />

Next Message by Hans is [15].<br />

[13] CousinIt: Occupational Psychosis. In [5], Hans asks the interesting question “why<br />

is it not obvious to everybody” that the question about happiness being the only true wealth

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 5<br />

is about a “nonsensical statement.” I agree that this is the more important question. As Hans<br />

points out, the cultural tactic or strategy (conscious or otherwise) underlying notions that we<br />

can be happy even when denied some kind <strong>of</strong> equity <strong>of</strong> collective wealth at the level <strong>of</strong> the<br />

individual amounts to what Veblen called a “trained incapacity” (this is referred to in Keneth<br />

Burke’s Permanence and Change). That is, we are acculturated to accept exploitation as a<br />

necessary condition <strong>of</strong> life, a veritable “law <strong>of</strong> nature,” and this, given that we are even able to<br />

recognize exploitation when we see it, at all! We aren’t capable <strong>of</strong> seeing or evaluating even<br />

our own material relations. We are also acculturated to not even notice or acknowledge the<br />

exploitation inherent in the capitalist system, or to downplay the negative effects that such<br />

exploitation has on the lives <strong>of</strong> individuals, including our own lives in this world. There<br />

is a strong connection to this conditioned ignorance <strong>of</strong> exploitation and a notion that one’s<br />

rewards for labors in this life will be gained in some life yet to come or by means other<br />

than material means. These are, in turn, connected to notions that poor people who do not<br />

enjoy the wealth that others do in capitalist society are somehow nonetheless capable <strong>of</strong> a<br />

“greater happiness” in their poverty; a “happiness” that, interestingly enough in the folklore<br />

<strong>of</strong> our time even emerges as a characteristic property <strong>of</strong> poverty in itself! Yet, by the same<br />

token, in this country, if one were able to objectively observe common behavior without<br />

such a debilitating bias that makes everything ‘appear’ OK, one might come away with the<br />

impression that we, the American citizenry, think that the proper response to any crisis,<br />

personal or collective, is to immediately go shopping, as President Bush suggested we do<br />

immediately after September 11, 2001. To me, in my own ‘sick’ ‘pinko-commie’ mind,<br />

this conditioned ignorance and response to the material conditions <strong>of</strong> our lives as a whole<br />

is not less than massively absurd and akin to denying that human activity has effects on the<br />

biosphere, such as denying the human factor in ‘global warming.’ Some <strong>of</strong> us probably even<br />

think that slavery is a thing <strong>of</strong> the past that we have effectively eradicated.<br />

In [4], Litsyemir suggests, in reference to [3] that we have the same (or similar) conditions<br />

<strong>of</strong> selective blindness here (in the U.S.? we should for clarity’s sake, state exactly what,<br />

where, or how when making such blanket statements) in that there is a systematic indoctrination<br />

that creates a blindness in regard to exploitation. Litsyemir suggests that “capitalism<br />

has become consumption.” In fact, the situation is much much worse than Litsyemir intuits.<br />

Some folks go so far as to suggest that capitalism and democracy are the same thing, if not<br />

necessarily connected. What is ignored in such a conception <strong>of</strong> democracy as ‘freemarket’<br />

capitalism is that in a truly democratic society the citizens could vote even on what kind <strong>of</strong><br />

economic system or currency is to be used in that society. By some accounts, capitalism,<br />

which creates great disparities <strong>of</strong> wealth amongst its participants giving rise to stratified<br />

socio-economic classes, is completely and diametrically the exact antithesis to democracy.<br />

By this account democracy is a sham amongst a society <strong>of</strong> participants who do not enjoy<br />

and wield a rough equality <strong>of</strong> material wealth as individuals. This is not something you will<br />

be able to find anywhere in the popular illiterature. They didn’t teach this to us in school.<br />

In both cases, the situation is one that is not just an inaccuracy <strong>of</strong> apprehension or efficiency<br />

<strong>of</strong> indoctrination, but rather an actual illness that amounts to a wasting-away <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human species potential as a result <strong>of</strong> a mental / socio-economic / emotional / biological<br />

infirmity that ends up having very real material and biological effects on the body <strong>of</strong> the<br />

human animal as a whole, if not on the biosphere. Burke (mentioned earlier) has an entire

6 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

chapter (taking from John Dewey, a famous American philosopher <strong>of</strong> the pragmatist school)<br />

on what he refers to as “occupational psychosis.” Basically, every society has a principal<br />

mode <strong>of</strong> production which ends up dictating the worldview necessary to promote and perpetuate<br />

that very modal productivity. Worldviews are very very all-encompassing, relatively<br />

rigid, and exclusive. Anything coming from outside <strong>of</strong> the popular worldview is essentially,<br />

from inside <strong>of</strong> that worldview, unthinkable.<br />

Following Burke, a person’s or a society’s interests (e.g., one’s “best interests”) must<br />

be differentiated from a person’s or a society’s interest in a topic or along an articulated<br />

continuum <strong>of</strong> ideas, activities, beliefs, values, etc. (though surely we can see how these<br />

are always everywhere immanently in positive or negative relationship). People will pay<br />

attention to what interests them, which may or may not be what is in their ‘best’ interest.<br />

Burke claims that greatest attention is paid to those things that play to what we are interested<br />

in, all else being pushed to the periphery or the ‘back burner’ on the range <strong>of</strong> salient issues<br />

and concerns. Clearly, upon reflection and perhaps upon hindsight, we see the difference<br />

between that which we are interested in and that which it is in our “best interest” to think,<br />

say, do, etc. Burke uses the example <strong>of</strong> the laborer, who is not necessarily interested in<br />

proletariat literature, though such literature might nonetheless have as its subject the best<br />

interests <strong>of</strong> the worker (37-38). We naturally pay attention to the things that interest us in<br />

the communications <strong>of</strong> others, in the sense that it is <strong>of</strong>ten said that one ‘hears what one wants<br />

to hear,’ <strong>of</strong>ten despite the nature <strong>of</strong> our ‘best interests’ or that which we ‘ought to’ hear.<br />

In a hunting society, because the means <strong>of</strong> survival is organized around the hunt, all other<br />

ideological elements and practices take on the imaginative characteristics <strong>of</strong> the hunt as<br />

general cultural template. In terms <strong>of</strong> human relationships, women are stalked and hunted;<br />

...a tribe which lives by the hunt may be expected to reveal a corresponding<br />

hunt pattern in its marriage rites, where the relation between man and<br />

woman may show a marked similarity to the relationship between huntsman<br />

and quarry. The woman will be ritually seized. Also, the highly problematical<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> hunting, its continual stressing <strong>of</strong> the sudden, or unexpected,<br />

might instigate a cultural emphasis upon the new (39).<br />

In a capitalist techno-consumerism, because all things are operationalized and determined<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> progress as well as debit or credit, human relationships also reflect the characteristics<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dominant method <strong>of</strong> survival (or mode <strong>of</strong> production). In the current capitalistconsumerist<br />

psychosis, apprehended as it is in a psychoanalytic (that congruent with everyday<br />

systems <strong>of</strong> patriarchal authoritarianism, reduces emotional and mental life by analysis to<br />

the oedipal) personalities, practices and behaviors are leveled-out and captured by a system<br />

<strong>of</strong> commodities, exchange, and institutionalization as ‘public mental health.’ Commodified<br />

human relations are bought and sold according to legal and economic enablements and<br />

constraints.<br />

Burke’s contention is that even our own society is subsumed by a psychotic split with the<br />

actual conditions <strong>of</strong> our own existence. We thus fall prey to a view <strong>of</strong> the world and our<br />

place in it that ultimately ‘cannot see’ the truth. This ultimately amounts to an illusion or

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 7<br />

hallucination <strong>of</strong> psychotic proportions. For Burke, societies, like individuals, suffer from<br />

pathological dis-ease.<br />

Reference<br />

Burke, K. (1984). Permanence and Change: An Anatomy <strong>of</strong> Purpose. Berkeley: <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> California Press.<br />

Message [13] referenced by [14], [15], and [686]. Next Message by CousinIt is [27].<br />

[14] Lev: Occupational Psychosis. I am interested in CousinIt’s contribution [13] as<br />

it takes a very different angle to that I have been considering in Hans’ [5] statement about<br />

“nonsense”. CousinIt discussion is primarily on the distortion <strong>of</strong> consciousness due to class<br />

and especially the need to transcend these contextual biases (they are rationally available and<br />

therefore can be transcended). On that point I delight in pointing out that Ricardo famously<br />

said that the interests <strong>of</strong> the landlord class are opposed to the interests <strong>of</strong> all other classes.<br />

For my part, I would like to look at the the pragmatics <strong>of</strong> the “nonsensical question”, “Can<br />

one say that happiness is the only true wealth?” is, in my opinion, more complex than Hans<br />

is giving it credit for. To be sure, if one phrases it as “Wealth is an input into the process <strong>of</strong><br />

living, while happiness is an output from the process <strong>of</strong> living”, yes, then it makes sense to<br />

write it <strong>of</strong>f as being pragmatically nonsense (as per the comment “laughter is the only kind<br />

<strong>of</strong> joke”). However, such claims <strong>of</strong> nonsense is dependent on whether happiness is only an<br />

output and wealth is only an input.<br />

As has been previously referenced, the Hellenes considered happiness to be an output<br />

based on intention, that is, happiness is generated from morally good intentions. One can<br />

certainly posit a situation where regardless <strong>of</strong> the outcome <strong>of</strong> their actions, a person with<br />

such an intent remains happy because they know that they acted righteously. Also previously<br />

referenced is a fairly hefty study which argues that some 50% is “set-point” (largely<br />

genetically derived), some 40% is intentions and a mere 10% is circumstances (p116). Now I<br />

personally think that the particular study is significantly prone to selection bias, but that does<br />

not change the fact that both genetics and intentions are a component to where happiness is<br />

described as an input to the process <strong>of</strong> living, rather than an output.<br />

Conversely, it is arguable whether ‘wealth’ is just an input to the processes <strong>of</strong> living.<br />

Whilst wealth has come to mean an accumulation <strong>of</strong> economic value, in a more general<br />

sense it means a measure <strong>of</strong> any resource, to which ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ can be relative markers<br />

<strong>of</strong> whatever resource is being measured. Now are these resources an input or an output <strong>of</strong><br />

the processes <strong>of</strong> living? It is quite arguable that they are both, as an input derived from both<br />

nature (e.g., richness in strength), social relations (e.g., richness in inherited ownership <strong>of</strong><br />

land, capital), and as an output in the manner described by Marx in the transformation from<br />

simple commodity production to capitalist commodity production.<br />

Apropos to my previous post, I would further argue that the happiness/wealth comparison<br />

has much to do with contextual conditions. I seriously doubt, regardless <strong>of</strong> genetics or<br />

intention, whether happiness is plausible for those who are in a state <strong>of</strong> perpetual hunger.<br />

Likewise, I cannot imagine a person deriving happiness from labouring in such a such an<br />

economy even in the most non-exploitative social arrangements; in the apocryphal words<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chief Seattle, it is not existence but survival. It is indeed notable that the landlord and

8 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

capitalist classes threaten the working and renting classes with precisely this sort <strong>of</strong> rental or<br />

wage regime, which accords with David Ricardo’s twin laws (The Law <strong>of</strong> Rent, The “Iron<br />

Law” <strong>of</strong> Wages) and this does raise the point that in some economic states, it is quite possible<br />

for the threat <strong>of</strong> ‘remorseless labour’ has been surpassed in economic conditions but due to<br />

exploitative social relations it still exists for the exploited.<br />

In summary, genetic and intentional happiness is only possible in economic conditions<br />

where necessities can be satisfied. This possibility <strong>of</strong> happiness as an input only becomes<br />

a reality depending on the degree <strong>of</strong> exploitation in social relations. Once this point is<br />

reached however happiness can be both an input (genetics, intentions) and an output (further<br />

accumulation <strong>of</strong> utilitarian wealth). Happiness and wealth are both inputs and outputs and<br />

their interaction is modified by concrete circumstances.<br />

Message [14] referenced by [15]. Next Message by Lev is [24].<br />

[15] Hans: How to Investigate a Totality. The discussion about this question was never<br />

as pr<strong>of</strong>ound as this year. CousinIt’s [13] and Lev’s [7] and [14] are extremely rich, much<br />

better than what I could have produced myself. Thank you for your contributions.<br />

Lev [7] finds my explanation in [5] simplistic. About this I’d like to say something. We<br />

are looking at a society. This is a totality, i.e., a system in which everything depends on<br />

everything. Where do you begin when you try to study a totality? You just have to make<br />

some simplifications. Therefore your argument can never have the force <strong>of</strong> a mathematical<br />

pro<strong>of</strong>. But I think my explanation gives me a framework which enables me to make sense <strong>of</strong><br />

a good portion <strong>of</strong> the answers to this question in the archives. Even better evidence would be<br />

to ask the writers <strong>of</strong> these answers whether my feedback based on my theory is convincing<br />

to them – but most <strong>of</strong> these writers are no longer available. This too, <strong>of</strong> course, is not an<br />

exact criterion. Maybe the best evidence would be whether my intervention based on this<br />

paradigm would enable them to make changes in society for the better. What I am trying to<br />

say is: there are criteria how to evaluate a theory, but they are not exact criteria.<br />

But we are under a time constraint here. Our philosophical discussion about wealth and<br />

happiness should not keep us from reading Capital. Does my interpretation <strong>of</strong> Marx in the<br />

currently assigned readings, see [12], make sense to you? We should turn our collective<br />

attention to the way how Marx argues that value comes from labor.<br />

Next Message by Hans is [18].<br />

Exam Question 32 is 25 in 2002fa, 28 in 2004fa, 33 in 2007SP, 32 in 2007fa, 32 in<br />

2008fa, 35 in 2011fa, and 32 in 2012fa:<br />

Exam Question 32 Does the use-value <strong>of</strong> a commodity depend on the person using it?<br />

[229] Scott: Use-value does not depend on the individual. What is a use-value? The<br />

usefulness <strong>of</strong> a commodity for human life makes it a use-value.<br />

The use-value <strong>of</strong> a commodity does not depend on the individual but on whether it satisfies<br />

a human need or want. For example a car is going to be a use value for me because it<br />

fulfills one <strong>of</strong> my human needs, but it’s not going to be a use value for my friend who is in a<br />

wheel chair and cannot drive. The use-value <strong>of</strong> a thing is therefore not one <strong>of</strong> the properties<br />

<strong>of</strong> the thing, but the relationship between these properties and human needs or wants that is<br />

attributed to the thing as if it was a property <strong>of</strong> the thing.

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 9<br />

Hans: I edited your original submission to make your answer more precise.<br />

(a) Wherever you had originally written “commodity” I replaced it by “thing.” Something does not have to be a<br />

commodity (i.e., produced for sale) in order to be a use-value.<br />

(b) Your last sentence was originally: “The use value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is not a property <strong>of</strong> a thing, but the<br />

relationship between the thing and human needs and wants.” This is almost a literal quote from the beginning <strong>of</strong> a<br />

sentence in the Annotations, but the beginning <strong>of</strong> the sentence alone, without the end, does not make much sense.<br />

I replaced it by the entire sentence from the Annotations (in fact, I edited my own sentence in the Annotations too,<br />

so you see here the version in the next edition <strong>of</strong> the Annotations).<br />

Next Message by Scott is [325].<br />

[231] Hans: Use-value versus neoclassical utility. My [2004fa:174] is “the” right answer<br />

to this question. Here it is again, for your convenience:<br />

No, it doesn’t. A thing has use-value if its properties are such that they<br />

are useful to humans. If Marx says that every commodity, in order to be<br />

exchangeable, must have use-value, he is thinking that it must be in principle<br />

usable, not that every single person will want to use it. If the question<br />

arises whether something is useful for a specific person, Marx uses the idiom<br />

“use-value for” that person, for instance he says that the commodity<br />

has no use-value for its producer. But without this “for,” use-values are<br />

independent <strong>of</strong> the individuals using the product.<br />

This is all you have to say in the exam, but let me give you a little background. This<br />

is a designated exam question because it highlights the difference between the classical<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> use-value and the neoclassical concept <strong>of</strong> utility. Utility is something subjective;<br />

it is the satisfaction which people derive from using a good. Use-value, by contrast, is<br />

objective; think <strong>of</strong> it as the physical properties <strong>of</strong> the good which make it useful for humans,<br />

or the menu <strong>of</strong> all possible uses <strong>of</strong> a thing. As I tried to explain in the Annotations in my<br />

comments to the first sentence <strong>of</strong> 126:1, the usefulness <strong>of</strong> a thing is a relative concept. It<br />

cannot be located in the thing alone, and also not in humans alone. The concept “use-value”<br />

attributes it to the thing, while the concept “utility” attributes it to the humans.<br />

By the way, despite the automatic message that this is an ungraded exam question, when<br />

answered during the extra credit period, these exam questions will be graded. But the extra<br />

credit period is almost over. It ends at 10:45 today (Sunday), which is 24 hours before<br />

tomorrow’s exam.<br />

Message [231] referenced by [256], [279], and [385]. Next Message by Hans is [256].<br />

Question 34 is 27 in 1995ut, 29 in 2003fa, 31 in 2005fa, 35 in 2007SP, and 34 in 2008fa:<br />

Question 34 Can you think <strong>of</strong> an example in which the quantity <strong>of</strong> something affects its<br />

quality, for instance some physical matter two litres <strong>of</strong> which are qualitatively different than<br />

one litre <strong>of</strong> it?<br />

[24] Lev: Quantity and Quality – and Crisis. The question <strong>of</strong> quantitative change effecting<br />

quality is a reasonably well-known matter <strong>of</strong> philosophical import and initially given<br />

its strong elucidation in Hegel’s “Science <strong>of</strong> Logic” (as referenced by Hans, [2007SP:2]).<br />

It is interesting that Hegel uses his particular definition <strong>of</strong> quality to illustrate evolution and

10 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

development through contradiction and negations, thereby becoming more fully “real” in the<br />

process and ultimately, in Hegelian metaphysics, the Spirit going beyond Nature.<br />

(“finitude is only as a transcending <strong>of</strong> itself”).<br />

It is perhaps not surprising that there are several well-known examples <strong>of</strong> quantitative<br />

change leading to qualitative change, starting from the most elementary to those which are<br />

most surprising and indeed counter-intuitive. Rollingrock [1995ut:6] suggests the application<br />

<strong>of</strong> heat to water as a very well-known example whereby at the critical quantitative<br />

temperatures <strong>of</strong> 0 and 100 degrees Celsius pure water at 1.0 Atm and 1.0G shall change in<br />

phase from solid, to liquid, to gas. I will raise the question however if this phase-shift, which<br />

can be understood as the form <strong>of</strong> the particle in different densities (solid the most dense, gas<br />

the least), actually represents a qualitative change.<br />

On the more counter-intuitive level, the behaviour <strong>of</strong> the Helium-3 isotope is an example<br />

<strong>of</strong> a particle decay (quantitative value) and extremely low temperatures where the Pauli<br />

Exclusion Principle is violated and the particle becomes superfluid.<br />

Multiple superfluid helium-4 particles coexist with the same quantum state. Likewise I<br />

would also like to raise the progress <strong>of</strong> logic systems where Godel’s incompleteness theorem<br />

(1931) which shows that no sufficiently strong formal system can prove its own consistency<br />

(i.e., at a certain level, a logic system can be either complete or consistent, but not both).<br />

Bresid [2003fa:2] provides an interesting example <strong>of</strong> the physiological biosystem and the<br />

interaction with anesthetics, in particular is<strong>of</strong>lurane, where a quantitative value can transform<br />

from the substance being an anesthetic to being an euthanasia agent. Hans responds<br />

[2003fa:3], quite appropriately, that the qualitative difference between an anesthetic agent<br />

and a euthanasia agent is quite moot: “Is it merely the same quality with different effects?”<br />

A matter which I find particularly interesting in the Bresid example is a closely related<br />

subject <strong>of</strong> crisis. Pithily elaborated in the opening pages <strong>of</strong> the now classic text <strong>of</strong> social theory<br />

“Legitimation Crisis” (Jurgen Habermas, Legitimationsprobleme im Spaetkapitalismus,<br />

1973). In medicine it represents a point where, regardless <strong>of</strong> individual will, the physiological<br />

system <strong>of</strong> an individual is tested to capacity in its ability to heal. In the environment,<br />

or social systems, it is also sensible to speak <strong>of</strong> crises, points in time and place where the<br />

capacity <strong>of</strong> the system is faced with a “life or death” test in its abilities to continue. In contemporary<br />

environmentalism it is typical to speak <strong>of</strong> a quantitative increase in temperature<br />

leading to a “tipping point” (between 2 and 3 degrees) where the qualitative effects are pr<strong>of</strong>oundly<br />

destructive. I am even prepared to go a bit out an a limb and refer to a crisis in<br />

literature, the point <strong>of</strong> the narrative where the protagonist, with the prior accumulation <strong>of</strong><br />

a quantity <strong>of</strong> aesthetic plot moments, either successfully confronts their antagonist (be that<br />

the setting, circumstances or another character or, in the case <strong>of</strong> tragedy, confronts their own<br />

weaknesses) as the climax <strong>of</strong> the story. Whilst on the aesthetic trajectory however, I will<br />

take the moment to strongly concur with Hans’ comment [2003fa:8] that Marx uses quality<br />

in the philosophical sense, meaning the properties belonging to the good itself, rather than<br />

the aesthetic judgment <strong>of</strong> subjective taste.

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 11<br />

Where this comes into play is the relationship between quality and crisis. Hegel argues<br />

that there is a ‘right’ quantity <strong>of</strong> a thing, it’s “measure”, and then in a particular example<br />

[2007SP:1] and [2007SP:2] the measure <strong>of</strong> breast implants is normally two. If there is a<br />

right quantity, it also stand to reason that there is a wrong quantity and - in the case <strong>of</strong> crisis<br />

- a quantity that is so different that the existing state <strong>of</strong> affairs are no longer stable. It makes<br />

me question - in reference to previous comments about David Ricardo’s notorious “Iron Law<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wages” - that if there were an automated rather than punitive welfare system where, as<br />

per the discourse <strong>of</strong> radical Georgists, each individual received a portion <strong>of</strong> the site-value<br />

<strong>of</strong> all economic land, that whether the labour market would be so radically changed by this<br />

quantity <strong>of</strong> automatic income that there would be a qualitative difference in the class conflict<br />

between capitalists and workers*. I note Marx’s footnote to John Locke in the opening<br />

pages <strong>of</strong> capital in this regard: “The natural worth [value] <strong>of</strong> anything consists <strong>of</strong> its fitness<br />

to supply the necessities, or serve the conveniences <strong>of</strong> human life”.<br />

Finally, I would like to conclude on Hans’ comments in [2007fa:37]. It was a different<br />

question, relating to valid exchange values vs exchange values, but the issue <strong>of</strong> quality and<br />

quantity is raised there. Marx argues that valid exchange values <strong>of</strong> a commodity represent<br />

equal content in quality. This is raised as a counter to the use <strong>of</strong> exchange-values which<br />

are quantified (by the highly distorted relations in supply and demand), but never qualified.<br />

In doing so, it seems that neoclassical economics engaged in a mass deception to take out<br />

qualitative questions **, as they would frustratingly lead to the conclusion <strong>of</strong> the primacy <strong>of</strong><br />

labour in value determination, along (if I may reference the Georgists twice) the commonality<br />

<strong>of</strong> economic land. As such qualitative questions had to be screened out <strong>of</strong> discussion,<br />

least the lead to political unpleasant consequences. “Political Economy”, the most important<br />

moral and scientific study <strong>of</strong> the 18th and 19th century, became merely “Economics”,<br />

heralding the era <strong>of</strong> the “dismal science”. That, in itself, is arguably a qualitative change<br />

brought on by the sheer weight <strong>of</strong> arguments elucidating class exploitation.<br />

* I have written on this relationship in the past and how the operation <strong>of</strong> the labour market<br />

are vastly different from the idealised “free choice” suggested by neoclassical apologists:<br />

“Working for Welfare in the Antipodes: An Incarnation <strong>of</strong> Wage-Slavery”<br />

http://bad.eserver.org/issues/2004/69/lafayette.html<br />

** William Stanley Jevons excluded; he considered the marginal analysis as complementary<br />

rather than exclusive or as a replacement to the labour theory <strong>of</strong> value.<br />

Message [24] referenced by [2008fa:20]. Next Message by Lev is [72].<br />

Question 35 is 20 in 1995WI, 35 in 2008fa, and 37 in 2012fa:<br />

Question 35 Bring other examples <strong>of</strong> relative “properties” such as beauty or use-value.<br />

[6] Litsyemir: My Neighbor Bought a Boat. My neighbor’s house is bigger than mine.<br />

He purchased additional commodities (in the form <strong>of</strong> upgrades), which I did not. These<br />

commodities make his house more “comfortable” for him. Comfort is not a property <strong>of</strong><br />

the home, but relative to my neighbor and his “need” to have a certain comfort level. The<br />

commodities he purchased - upgraded cabinetry, tile flooring, wrought iron railing, etc - all<br />

add to his level <strong>of</strong> comfort, a relative property <strong>of</strong> the commodities.

12 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

The same neighbor also bought a boat. 35 footer. With flames painted on the side to make<br />

it look faster. It’s the only one on the street. To tow his boat, he purchased a nice, new, top <strong>of</strong><br />

the line truck. He immaculately cares for his boat and his truck. The slightest speck <strong>of</strong> dust<br />

is swept away or wiped <strong>of</strong>f as quickly as possible. These commodities give him “prestige”.<br />

Again, prestige is only a relative property he attaches to the commodities.<br />

I try to use a day planner to keep track <strong>of</strong> my work, schooling and family life. My planner<br />

helps me feel “organized”. Of course, being organized is a relative property unique to me<br />

and my use <strong>of</strong> the day planner. To anyone, it might mean something entirely different.<br />

These are just a few <strong>of</strong> the examples I came up with for other relative “properties”. And<br />

yes, my neighbor does have a bigger house than I do. But he doesn’t have the boat or the<br />

truck. I kind <strong>of</strong> wish I did. Just for the opportunity to “be a man.”<br />

Hans: I don’t quite get it why you said “he doesn’t have the boat or the truck.” I thought earlier you said he did.<br />

Regarding your first example: Comfort meets the human needs for a relaxing and protected home environment.<br />

The “need to have a certain comfort level” is a derivative need created in a society in which neighbors vie for social<br />

status.<br />

Litsyemir: In response to your question Hans, I was using the purchase <strong>of</strong> a boat and truck as an example to<br />

illustrate the point. I should have been clearer about that. My apologies.<br />

First Message by Litsyemir is [4].<br />

Multiple Choice Question 46 is 599 in 2000fa and 36 in 2001fa:<br />

Multiple Choice Question 46 Which <strong>of</strong> the following is closest to Marx’s theory:<br />

(a) The use-value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is the utility one gets from using it; the exchange-value is<br />

the utility one gets from using those things one can trade the commodity for.<br />

(b) Use-value is the quality <strong>of</strong> the commodity, and exchange-value is its quantity.<br />

(c) Use-value is the use a commodity has to its owner, exchange-value is the use a commodity<br />

has to others.<br />

(d) Just as a painter needs a canvas as a carrier on which he can paint his painting, the<br />

capitalist needs a use-value as a carrier for the exchange-value <strong>of</strong> the products his workers<br />

have produced.<br />

[256] Hans: Exchange-value a passenger <strong>of</strong> use-value. This was one <strong>of</strong> the multiple<br />

choice questions on Monday.<br />

(a) turns both use-value and exchange-value into human attributes, while Marx looks at<br />

them as the social properties <strong>of</strong> the commodities themselves. See [231]. If you answered (a)<br />

you got partial credit.<br />

(b) Everything has a quality and a quantity, but not every use-value has an exchangevalue.<br />

Use-value and exchange-value are not two sides <strong>of</strong> the same thing. This answer is<br />

wrong because it takes a too harmonious view <strong>of</strong> our social relations. You should think <strong>of</strong><br />

use-value and exchange-value as two strangers locked into the same room. Before long they<br />

will begin fighting.<br />

(c) is wrong too. It turns exchange-value into a simple everyday human emotion, and<br />

ignores the social structures which must be in place for an economy to be an exchangeeconomy<br />

(private property laws etc.). If I desire my neighbor’s wife, this does not magically<br />

make her exchangeable. The same is true if I desire his motorcycle.

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 13<br />

(d) is closest to Marx’s theory. It shows the distance between use-value and exchangevalue<br />

despite the fact that a commodity has to have a use-value in order to have an exchangevalue.<br />

Message [256] referenced by [2009fa:8]. Next Message by Hans is [268].<br />

Question 61 is 61 in 2008fa and 64 in 2010fa:<br />

Question 61 Marx discusses at length the question whether value is intrinsic to the commodity<br />

or relative. What is the view <strong>of</strong> neoclassical economics? Does it consider value to<br />

be intrinsic or relative?<br />

[16] Jenn: (content A form 95% weight 50%) Marx discusses whether values are intrinsic<br />

or relative at length. Neoclassical economics considers value to be based on an equilibrium<br />

<strong>of</strong> cost in dollars <strong>of</strong> supply and perceived or observed demand. Although I believe this<br />

way <strong>of</strong> thought takes relative value into account somewhat by using demand, it does place<br />

more <strong>of</strong> an intrinsic value on products. This intrinsic value is a result <strong>of</strong> the emphasis placed<br />

on supply costs, in dollars.<br />

Message [16] referenced by [18] and [2008fa:42]. Next Message by Jenn is [61].<br />

[18] Hans: Does Neoclassical Theory Really Have a Subjective Concept <strong>of</strong> Value?<br />

Jenn says in [16] that neoclassical theory mainly uses an intrinsic concept <strong>of</strong> value (in cost<br />

accounting), although relative value is somewhat taken into account through demand.<br />

I agree but would put a different spin on it. If you read a neoclassical textbook, value<br />

is defined as a relative concept. The value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is measured by the marginal<br />

utility you receive from using the commodity. This means the value rests in how you see<br />

the commodity, not in the commodity itself. This is called the subjective concept <strong>of</strong> value,<br />

because value comes from the subject (the user <strong>of</strong> the commodity), not the commodity itself.<br />

But when a modern firm does its accounting, it doesn’t follow this textbook wisdom but<br />

uses an objective concept <strong>of</strong> value, which attaches the value to the commodities.<br />

The contradiction between intrinsic and relative value, which Marx discusses in the assigned<br />

readings, is therefore present in modern business and economic practice.<br />

To resolve this contradiction, Marx makes a couple <strong>of</strong> inferential steps which bring him to<br />

the conclusion: value is not created in commodity circulation but it is the surface reflection<br />

<strong>of</strong> something the commodities receive in production.<br />

The class materials discuss Marx’s steps in more detail, and I will give an overview tomorrow<br />

in class. Without getting into the details <strong>of</strong> Marx’s arguments right now, it is perhaps<br />

helpful to say that a look at modern cost accounting leads to the same conclusion. I.e., the<br />

conclusions which Marx’s Capital derives in a specific and not always easy to follow fashion<br />

can also be gained by different (but related) kinds <strong>of</strong> arguments. Here is this alternative<br />

argument:<br />

In the practice <strong>of</strong> cost accounting, the value <strong>of</strong> a product is determined by its cost. There<br />

are two things wrong with this:

14 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

(a) This is a circular definition! The cost <strong>of</strong> a good is simply the value <strong>of</strong> those goods<br />

entering its production, i.e., if you define value by cost you define the value <strong>of</strong> one good by<br />

the value <strong>of</strong> other goods and still don’t know where any <strong>of</strong> these goods get their value from.<br />

(b) Usually, the value <strong>of</strong> a good is greater than its cost; again, this indicates that you<br />

cannot determine value by cost.<br />

These are enough contradictions to look for the source <strong>of</strong> value not in circulation at all<br />

but elsewhere (a logical candidate is production).<br />

Message [18] referenced by [21], [307], [2008fa:42], [2008fa:46], [2008fa:583], [2009fa:1023], [2010fa:23], and<br />

[2011fa:498]. Next Message by Hans is [20].<br />

[21] SnatchimusMaximus: (graded A) I have to say that neoclassical economics views<br />

value as relative. If value were intrinsic then prices would never fluctuate because a commodity’s<br />

value is ipso facto. Thus, if prices never fluctuate then markets can never adjust and<br />

the happy state <strong>of</strong> equilibrium would never be. Neoclassical economics argues that value is<br />

indeed relative because markets are interrelated. Thus a commodity may be relative as an<br />

inferior good or normal good, or as a substitute or complement. Neoclassical economics<br />

also gives us the production function that states firms will produce until AC=MC. Hence if<br />

a commodity’s supply is dictated by its costs and costs are relative to factors <strong>of</strong> production,<br />

then a commodity’s value is relative not only to other related goods (i.e. inferior goods,<br />

normal goods, complements, etc), but the commodity’s value is also relative to its factors <strong>of</strong><br />

production. It seems the only thing intrinsic about a commodity is its costs, and even those<br />

fluctuate in the long run.<br />

Hans: Good thinking. That fluctuations <strong>of</strong> prices are necessary for adjustment to equilibrium is also a point made<br />

by Marx in 195:2/o. About the relation between prices and costs see my [18].<br />

Message [21] referenced by [2008fa:583]. Next Message by SnatchimusMaximus is [161].<br />

[307] Paul: The neoclassical view <strong>of</strong> value is definitely relative. This is because prices are<br />

always fluctuating and if value was intrinsic this would not be possible. As a result <strong>of</strong> prices<br />

fluctuating, it gives markets a chance to adapt and conform so they are able to reach the equilibrium<br />

<strong>of</strong> the expenditure <strong>of</strong> supply and the apparent demand. Value is also relative for the<br />

fact that the consumer, in reality, decides the value <strong>of</strong> any given commodity. Hans [18] says<br />

that the value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is measured by the marginal utility you receive from using the<br />

commodity. Therefore different people could believe that a commodity is worth an entirely<br />

different value. Take a blood sugar monitor, a diabetic would value this product extremely<br />

high while a non-diabetic has no need for this and would deem this product valueless. This<br />

demonstrates that the given value <strong>of</strong> a commodity can be biased and personal.<br />

Hans: Yes, in neoclassical (i.e., mainstream) theory, prices are derived from utility. There is not the strict separation<br />

which Marx makes between “value” and “use-value,” but the concept <strong>of</strong> utility could be considered their concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> value. This value is not intrinsic in the commodities but relative, since it depends on the usefulness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

commodity to its owner.<br />

Next Message by Paul is [313].<br />

[347] Bennett: The view <strong>of</strong> neoclassical economics is that <strong>of</strong> maximizing your utility,<br />

or simply the satisfaction that is associated with your consumption <strong>of</strong> goods and services.<br />

Another neoclassical view is that buyers look to increase their gains from purchasing goods,<br />

and they achieve this by increasing their purchases <strong>of</strong> products until their gain from another<br />

unit is balanced by what they have to sacrifice to obtain it. The neoclassical view on value is<br />

that value is relative to the value that the person purchasing the product or service gives it.

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 15<br />

Next Message by Bennett is [348].<br />

[361] Ande: To me the view <strong>of</strong> neoclassical economics is that value is intrinsic to the<br />

commodity rather than relative. They view items to be intrinsic because there is really no<br />

such thing as a relative value <strong>of</strong> a commodity. Because <strong>of</strong> all the use values and exchange<br />

values there could never be a relative value <strong>of</strong> any certain commodity. You could not have a<br />

bag <strong>of</strong> rice that has a relative value to a can <strong>of</strong> soda. It does not work like that; value has to be<br />

intrinsic and the neoclassical economics portrays this same view. This is how I interpreted<br />

it through the many readings <strong>of</strong> Marx. With money, use value and exchange value there is<br />

no way a commodity can have a value that is relative, all the values <strong>of</strong> the commodities are<br />

intrinsic, I believe this and in reading all the articles I believe that this is the same view as a<br />

neoclassical economics.<br />

Hans: I am not sure you understand that “neoclassical” economics is the mainstream economics which explains<br />

prices by demand and supply, and demand by utility functions. The value theory implicit in mainstream economics<br />

is relative or non-intrinsic in two ways:<br />

(a) since value is marginal utility, it does not rest in the commodity but in the person using the commodity.<br />

(b) Neoclassical economics does not need absolute levels <strong>of</strong> utility but only relative levels, it needs to know<br />

whether A or B is preferred.<br />

Next Message by Ande is [362].<br />

[382] Allen: In neoclassical economics value is considered to be relative. Value is relative<br />

because commodities will change prices due to changes in the economy, such as stated<br />

by Marx in 126:2. The actual value <strong>of</strong> the item changes relative to proportions and also<br />

exchange-value <strong>of</strong> an item remains relative to the commodity and changes along with different<br />

circumstances.<br />

Hans: This is Marx’s argument why exchange-value does not seem to be intrinsic to the commodity. Neoclassical<br />

economics uses the entire apparatus <strong>of</strong> the utility function to explain exchange-values, and this is indeed a relative<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> value, since the utility function is anchored in the user <strong>of</strong> the commodity, not the commodity itself.<br />

Message [382] referenced by [529]. Next Message by Allen is [385].<br />

[529] Alcameron: The neo classical view <strong>of</strong> the exchange <strong>of</strong> a commodity is that its value<br />

is relative rather than intrinsic. The very nature <strong>of</strong> the term exchange value helps us realize<br />

that the value is subject to change based on the particular exchange. Depending on the time<br />

and place (which market) you are in your commodity could have a higher or lower exchange<br />

value. Another important factor is labor and how much is in that commodity. The exchange<br />

value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is directly related to the amount <strong>of</strong> labor in that commodity.<br />

Hans: As Allen in [382], you are not describing neoclassical, i.e., mainstream economics here but you give Marx’s<br />

arguments why value does not seem intrinsic. Then in your last two sentences you are switching abruptly to value<br />

determined by labor, which is something intrinsic.<br />

Next Message by Alcameron is [530].<br />

Question 62 is 36 in 1996ut, 33 in 1997ut, 65 in 2010fa, and 73 in 2011fa:<br />

Question 62 Formulate in your own words the two contradictory statements Marx makes<br />

about the commodity when he introduces exchange-value.<br />

[283] Bmellor: Contradictory statements about the commodity. We can look at the<br />

contradictions as follows: we are all familiar with the “relativity and variability <strong>of</strong> exchange<br />

proportions.” Meaning that at different times and different places commodities might be<br />

exchanged in extravagant proportions. But in other parts Marx introduces the manifestation<br />

<strong>of</strong> exchange-value as something anchored in the commodity, as a second property which

16 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

commodities have in addition to their use-values, this is an item we are familiarized with<br />

while reading Marx’s thoughts. These two items are contradictory.<br />

Next Message by Bmellor is [288].<br />

[302] Inter: Revisiting the exchange-value contradiction. The exchange-value contradiction,<br />

that Marx explores, seems to be a contradiction <strong>of</strong> terms. Namely, that on the<br />

one hand Marx explains that the exchange-value <strong>of</strong> a commodity is determined from the<br />

relation it shares with another commodity. This relation is highly variable and based on<br />

circumstance. While on the other hand exchange-value is something that is inherent to the<br />

commodity. This is a contradiction because if exchange-value is inherent to the commodity<br />

then it stands to reason that it cannot be based on relations with other commodities.<br />

In my test response, I failed to adequately explain the contradiction, because I was focused<br />

on the relative nature <strong>of</strong> exchange-value that a commodity has. I did not fully develop<br />

the idea that exchange-value is inherent to the commodity, but rather developed the idea that<br />

use-value is inherent to the commodity.<br />

Next Message by Inter is [305].<br />

[306] Dentist: Exchange-value was at first introduced as a property that was actually<br />

possessed by and intrinsic to commodities. From this, the contradiction arises in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

exchange-relations. Because how can a property be specific to each commodity, and yet at<br />

the same time be completely relative when compared with other commodities?<br />

By an analysis <strong>of</strong> the conflict that exchange-value is attached to the commodity and yet<br />

entirely relative, the solution comes to the surface that exchange-value is not the particular<br />

essence or substance within the commodity, but it is the expressor <strong>of</strong> that substance. It is<br />

therefore this expression that is relative and not the actual properties <strong>of</strong> the commodities<br />

themselves, and that this substance is something entirely different from “exchange-value.”<br />

Later we go on to learn that this substance (value) is ultimately determined by labor.<br />

Next Message by Dentist is [311].<br />

[320] Sparky: Marx’s contradictory statements about exchange value are-<br />

1. The exchange value is something that is attached, a part <strong>of</strong> a commodity’s use-value.<br />

Exchange proportions is not up to a stand-alone commodity, it is up to its relation to another<br />

commodity, which is affected by other, outside, circumstances, which can change with the<br />

weather.<br />

2. That the exchange value is not something that belongs to a inner necessity, as said in<br />

the annotations. It shows that the relation <strong>of</strong> the commodity compared to other commodites<br />

is the real selling price <strong>of</strong> the commodites.<br />

Next Message by Sparky is [467].<br />

[325] Scott: 2 contradictory statements. When Marx introduces the exchange value he<br />

contradicts himself. He first says an exchange value <strong>of</strong> a commodity has a worth inherent in<br />

a good. He later says that exchange value is determined by the circumstances outside the <strong>of</strong><br />

exchange value. Marx doesn’t say that these statements are either true or false, but he says<br />

there must be more to the problem than he sees. Hans [1997ut:13] wrote, “The contradictory<br />

evidence surrounding the exchange value is an indication that the exchange value reaches<br />

into the invisible core <strong>of</strong> the economy. Therefore we have to take a closer look, which<br />

probes beneath the surface.” Bobdog [2004fa:10] gave a great example comparing this to a

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 17<br />

man “standing inside a building who has trouble understanding what makes the trees sway<br />

back and forth.” Marx is the same way, he only sees what is happening on the surface but to<br />

come to any conclusion he is going to have to go beneath the surface.<br />

Next Message by Scott is [326].<br />

[374] Mitternacht: graded A Contradictory statements about exchange-value. In the<br />

section where Marx introduces exchange-value he quickly comes to a contradictory point.<br />

Which is his way <strong>of</strong> uncovering truths and for seeing things as they truly are.<br />

He shows that on the one hand the exchange-value <strong>of</strong> a commodity appears to be something<br />

that is inherent to the commodity. Since a commodity may be exchanged at set amount<br />

for various other things in different measures it would appear that this exchange-value is<br />

inherent in the commodity itself.<br />

He also demonstrates that the exchange-value for a particular thing ends up being variable<br />

depending on other conditions which contradicts the first discovery that exchange-value<br />

appears to be inherent to the commodity.<br />

Upon looking more closely Marx finds that exchange-value is just an echo, or surface<br />

reflection <strong>of</strong> an immaterial value that lies within the commodity. The value is provided by<br />

labor in the production <strong>of</strong> the commodity.<br />

Next Message by Mitternacht is [784].<br />

[379] Rey: graded A In forming statements regarding exchange value Marx seemingly<br />

forms a contradiction. In Marx’s earliest introduction <strong>of</strong> a commodity’s exchange value, he<br />

presents exchange value as being independently anchored within the commodity. In addition<br />

to the idea that exchange value is anchored within a commodity, Marx describes exchange<br />

value as a second property <strong>of</strong> a commodity. This second property is described by Hans on<br />

page 20 <strong>of</strong> his annotations as “a second property, which commodities have in addition to<br />

their use-values.” In this case the exchange value is only “expressed” in the actual exchange.<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> when or where the commodities are exchanged their values remain constant.<br />

In summarizing this approach, the exchange <strong>of</strong> commodities only “expresses” their value<br />

rather than defines it. The other half <strong>of</strong> the contradiction comes as Marx discusses the effect<br />

that variables such as time and place, can have on the exchange value. The fact that exchange<br />

value is connected somehow to the actual exchange, suggests that exchange value is in fact<br />

not anchored within a commodity. Marx is appearing to state that a certain commodity has<br />

more or less value based on the time and place <strong>of</strong> an exchange. According to this thought<br />

the exchange <strong>of</strong> commodities defines value rather than simply expressing it.<br />

Hans: You have to distinguish more explicitly between exchange value and value. The weakest point in your little<br />

essay is the sixth sentence where you without comment go from exchange-value over to value. Exchange-value is<br />

a surface category, value is a category <strong>of</strong> the underlying sphere <strong>of</strong> production. Exchange-value is the expression<br />

<strong>of</strong> the value. At the very beginning Marx only talks about exchange-value; he has not yet gotten to the point that<br />

exchange-value is remotely controlled, i.e., the expression <strong>of</strong> some aspect <strong>of</strong> social production. If you only look<br />

at exchange-value without knowing yet about value, then the contradiction is that exchange-value seems inherent<br />

in the commodity (because it is the expression <strong>of</strong> something inherent, namely, value), and exchange-value seems<br />

relative (because this expression is an expression in the surface exchange relations).<br />

In your in-class answer you have underlined seemingly in the first sentence. Marx would still call it a contradiction<br />

(not just a seeming contradiction), even if it can be explained. Marx thinks that reality is full <strong>of</strong> contradictions,<br />

and I think this is indeed a helpful way <strong>of</strong> looking at things.<br />

Next Message by Rey is [386].

18 <strong>2008SP</strong> Econ 5080 U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong><br />

[405] Trailrunner: content A late penalty 1% Exchange-value is related to what society<br />

will exchange regarding one product for another - an equality <strong>of</strong> each commodity, regardless<br />

<strong>of</strong> its use value. This would be the relative or relational expression <strong>of</strong> the two commodities.<br />

But there is also the instrinsic expression <strong>of</strong> the commodity which takes us to looking at what<br />

the commodity really is. Thus, we would look at the commodity as an independent unit. We<br />

would recognize that the commodity can be exchanged for many other commodities and in<br />

many different proportions. This also looks at the labor that is involved in the production <strong>of</strong><br />

the commodity.<br />

Therefore, exchange value is not only about what it can be exchanged for on the market,<br />

but for what it actually is and is made up <strong>of</strong>.<br />

Next Message by Trailrunner is [406].<br />

[590] Wade: The exchange value is decided by the formality <strong>of</strong> the exchange.<br />

A commodity’s importance is decided by the exchange-value.<br />

Next Message by Wade is [731].<br />

Question 64 is 63 in 2007fa, 64 in 2008fa, 66 in 2009fa, 67 in 2010fa, 61 in 2012fa, and<br />

67 in Answer:<br />

Question 64 The French economist Le Trosne wrote that the value <strong>of</strong> a thing consists in<br />

its exchange-proportions with other things. Does Marx agree with this, or how would he<br />

re-formulate this proposition to make it correct?<br />

[17] Chris: Le Trosne’s exchange value quote. It appears from select passages in Marx’s<br />

Capital Volume 1 that Marx does think that exchange value is determined by the other objects<br />

for which it would be exchanged. However, I do not believe that he would format this<br />

opinion like Le Trosne. Marx does suggest in Capital V. 1 on page 126 that “exchange-value<br />

appears first <strong>of</strong> all as a quantitative relation, the proportion, in which use-values <strong>of</strong> one kind<br />

exchange for use-values <strong>of</strong> another kind.” Therefore, Marx does appear to be insinuating<br />

that an object’s exchange value is determined by the item for which it would be exchanged.<br />

However, Marx also mentions the importance <strong>of</strong> an object’s use value. It is in the use value<br />

that I feel Marx would re-formulate Le Trosne’s proposition.<br />

Earlier, on the same page in Capital V.1 (pg. 126), Marx suggests that a use value is<br />

simply “the usefulness <strong>of</strong> a thing.” Therefore, I think it is important to bring up the notation<br />

that one person may value an item’s usefulness differently depending on each person’s<br />

own desire to need or want its usefulness. This notation would also correlate directly to an<br />

object’s exchange value. As Marx also suggests, “use-values are only realized in use or in<br />

consumption (pg. 126).” So, we must assume or hope that the person realizing the use-value<br />

will use all <strong>of</strong> its value, or use it to the point where the person is satisfied.<br />

After reading the passages on page 126 and 127 <strong>of</strong> Capital V.1, I would presume that<br />

Marx is suggesting that a thing’s exchange value is considered as well as its use value.<br />

Therefore, Le Trosne’s quote is partly correct in Marx’s mind. I would also like to mention<br />

that Marx would re-formulate his idea <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> a thing exactly as he does on page<br />

126 and 127 <strong>of</strong> Capital V.1. On these pages he goes into great detail to explain use-value<br />

and exchange value. He then presents a commodity exchange example to give life to his

U <strong>of</strong> <strong>Utah</strong> Econ 5080 <strong>2008SP</strong> 19<br />

explanations. These two pages introduce an important idea <strong>of</strong> placing value on given objects<br />

and can be considered a re-formulation <strong>of</strong> Le Trosne’s respective quote.<br />

Hans: You are trying to read Marx closely, but you are still overlooking a couple <strong>of</strong> things:<br />

(a) Marx always develops his thoughts, and usually very slowly. He has a much longer breath than most modern<br />