Stability Across Cohorts in Divorce Risk Factors - Bishop Ireton High ...

Stability Across Cohorts in Divorce Risk Factors - Bishop Ireton High ...

Stability Across Cohorts in Divorce Risk Factors - Bishop Ireton High ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 331<br />

STABILITY ACROSS COHORTS IN DIVORCE RISK<br />

FACTORS*<br />

T<br />

JAY D. TEACHMAN<br />

Over the past quarter-century, many covariates of divorce have been identified. However, the<br />

extent to which the effects of these covariates rema<strong>in</strong> constant across time is not known. In this<br />

article, I exam<strong>in</strong>e the stability of the effects of a wide range of divorce covariates us<strong>in</strong>g a pooled<br />

sample of data taken from five rounds of the National Survey of Family Growth. This sample <strong>in</strong>cludes<br />

consistent measures of important predictors of divorce, covers marriages formed over 35<br />

years (1950–1984), and spans substantial historical variation <strong>in</strong> the overall risk of marital dissolution.<br />

For the most part, the effects of the major sociodemographic predictors of divorce do not vary<br />

by historical period. The one exception is race. These results suggest that the effects associated with<br />

historical period have been pervasive, simultaneously alter<strong>in</strong>g the risk of divorce for most marriages.<br />

he <strong>in</strong>creased prevalence of divorce, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with its well-known consequences for<br />

the well-be<strong>in</strong>g of men, women, and children (Amato 2000; Cherl<strong>in</strong>, Chase-Lansdale, and<br />

McRae 1998; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994), has spurred efforts to understand its determ<strong>in</strong>ants.<br />

Us<strong>in</strong>g various methods and data from different historical periods, researchers<br />

have l<strong>in</strong>ked numerous social, demographic, and economic variables to divorce. DaVanzo<br />

and Rahman (1993), Faust and McKibben (1999), and White (1990) reviewed this extensive<br />

literature. The list of variables considered is long and the results have varied, but a<br />

small number of sociodemographic variables have been l<strong>in</strong>ked consistently to the risk of<br />

divorce. These variables <strong>in</strong>clude age at marriage, education, premarital births and conception,<br />

religion, parental divorce, and race.<br />

Unfortunately, little research has attempted to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of<br />

divorce are <strong>in</strong>variant across historical time even though there are reasonable theoretical,<br />

albeit slimmer empirical, grounds for expect<strong>in</strong>g the effects of various predictors of divorce<br />

to vary across time. In my study, I tested the equality of effects across time us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

pooled sample of data taken from five rounds of the National Survey of Family Growth<br />

(NSFG); the NSFG <strong>in</strong>cluded consistent measures of important predictors of divorce, covered<br />

marriages formed over 35 years (1950–1984), and spanned substantial historical<br />

variation <strong>in</strong> the overall risk of marital dissolution. With the exception of race, I found that<br />

the effects of the major sociodemographic predictors of divorce do not vary across time.<br />

These results <strong>in</strong>dicate that the effects of historical period have been pervasive, at least<br />

over the period covered by this research.<br />

WHY SHOULD EFFECTS VARY OVER HISTORICAL TIME?<br />

There is no generally accepted theory of divorce, although the predom<strong>in</strong>ant perspectives<br />

all rely on some notion of the exchange of expressive and <strong>in</strong>strumental goods and services<br />

between husbands and wives (Becker 1991; Becker, Landes, and Michael 1977;<br />

Oppenheimer 1994, 1997; Ruggles 1997). The assumption is that marriage is beneficial<br />

because mutual <strong>in</strong>terdependence generated by exchange <strong>in</strong>creases the well-be<strong>in</strong>g of each<br />

*Jay D. Teachman, Department of Sociology, Western Wash<strong>in</strong>gton University, Bell<strong>in</strong>gham, WA 98225-<br />

9081; E-mail: teachman@cc.wwu.edu. I thank Kyle Crowder, Mick Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham, and the anonymous reviewers<br />

for their many helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.<br />

Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002: 331–351 331

332 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

spouse beyond what would be achieved if they were not married. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, anyth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that dim<strong>in</strong>ishes the real or perceived ga<strong>in</strong>s to marriage constitutes a risk factor for marital<br />

disruption.<br />

In the face of chang<strong>in</strong>g rates of divorce, to assume that the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of divorce<br />

have rema<strong>in</strong>ed constant over time is to assume that changes <strong>in</strong> the real or perceived ga<strong>in</strong>s<br />

to marriage have occurred uniformly across all marriages. This is a strong assumption to<br />

make without the support of substantial prior evidence, and there are reasonable theoretical<br />

arguments that lead to the expectation that the effects of some predictors of divorce<br />

will vary across time. I outl<strong>in</strong>e a few of these arguments next.<br />

First, consider the possibility that <strong>in</strong>dividuals with similar characteristics make different<br />

decisions about divorce because they react differently to changes across time <strong>in</strong> the<br />

nature of the exchange between husbands and wives. For example, consider the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

changes <strong>in</strong> the context surround<strong>in</strong>g marriage. Over the past half-century, attitudes toward<br />

divorce and nonmarital liv<strong>in</strong>g have become dramatically more forgiv<strong>in</strong>g (Cherl<strong>in</strong> 1992;<br />

Thornton 1989), and opportunities to form <strong>in</strong>timate unions and raise children outside marriage<br />

have expanded tremendously (Bumpass and Sweet 1989; Bumpass, Sweet, and<br />

Cherl<strong>in</strong> 1991; Mann<strong>in</strong>g and Smock 1995; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Morgan and<br />

R<strong>in</strong>dfuss 1999; South 1999). In addition, <strong>in</strong>creased equality <strong>in</strong> gender roles and <strong>in</strong> the<br />

structure of the economy have weakened the traditional economic <strong>in</strong>terdependence of men<br />

and women (Bianchi 1995; Oppenheimer 1994, 1997; Ruggles 1997). Thus, concurrent<br />

with <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> alternatives to marriage, there has been a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the mutual dependence<br />

between husbands and wives on the basis of a traditional division of labor between<br />

market and nonmarket activities.<br />

However, these changes have not affected all marriages uniformly. For example, South<br />

(2001) suggested that <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>stitutional supports for unmarried mothers, <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

with more liberal gender-role attitudes, have made it easier for employed wives to use<br />

their economic resources to leave unsatisfactory unions. South also noted that decreased<br />

occupational sex segregation has <strong>in</strong>creased the opportunity for employed married women<br />

to meet men who may be better matches than their current partners. The result of these<br />

changes should be an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly positive effect of married women’s employment on<br />

divorce, an expectation consistent with South’s empirical f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

The second possible l<strong>in</strong>k between changes <strong>in</strong> the context of marriage to the risk of<br />

divorce is even more straightforward. When there are few options to marriage and divorce<br />

is uncommon, the effects of any traits that are positively l<strong>in</strong>ked to the risk of divorce will<br />

be suppressed. However, as the barriers to divorce wane and alternatives to marriage become<br />

more common, the effects of these traits may beg<strong>in</strong> to be expressed <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

risk of marital disruption. Some evidence for this process has come from behavioral geneticists,<br />

who have found little to no evidence for the heritability of divorce when rates of<br />

divorce are low (Turkheimer et al. 1992) but substantial evidence for heritability when<br />

divorce is more common (Jock<strong>in</strong>, McGue, and Lykken 1996; McGue and Lykken 1992).<br />

Behavioral geneticists argue that heritability operates through the <strong>in</strong>heritance of personality<br />

traits that <strong>in</strong>crease the risk of marital dissolution. Indeed, a number of personality<br />

traits have been l<strong>in</strong>ked to the risk of divorce (Eysenck 1980; Jock<strong>in</strong> et al. 1996; Johnson<br />

and Harris 1980; McGue and Lykken 1992; Rockwell, Elder, and Ross 1979). It is not<br />

illogical to expect that at least some of the common demographic predictors of divorce are<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ked to different personality traits. For example, Kiernan (1986), us<strong>in</strong>g data from Brita<strong>in</strong>,<br />

found that women who marry younger exhibit higher levels of neuroticism, and higher<br />

levels of neuroticism are l<strong>in</strong>ked to an <strong>in</strong>creased risk of divorce. A variety of research has<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ked other measures of social psychological function<strong>in</strong>g, such as self-esteem, to sociodemographic<br />

characteristics like early and premarital fertility (Coley and Chase-Lansdale<br />

1998; Plotnick 1992; South 1999) and premarital cohabitation (Ax<strong>in</strong>n and Thornton 1992;<br />

Clarkberg, Stolzenberg, and Waite 1995; Thomson and Colella 1992).

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 333<br />

A third alternative may be that changes <strong>in</strong> the context of marriage have not occurred<br />

uniformly for all Americans. For example, over the past 40 years, blacks have been more<br />

likely than whites to delay marriage, to experience premarital fertility, and to cohabit<br />

outside marriage (Ellwood and Crane 1990; Teachman 2000). To some extent, these differences<br />

have emerged because the marriage markets <strong>in</strong> which blacks and whites operate are<br />

substantially different (Lichter, LeClere, and McLaughl<strong>in</strong> 1991; Lichter et al. 1992) and<br />

have diverged over time (McLanahan and Casper 1995), with blacks <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly subject to<br />

conditions less favorable to the formation and ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of marriages. One consequence<br />

of these different rates of change may be that, relative to whites, blacks who marry are an<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly select group who are relatively more committed to the <strong>in</strong>stitution of marriage.<br />

This result suggests a slower <strong>in</strong>crease over time <strong>in</strong> rates of divorce for blacks than for whites,<br />

an expectation that is consistent with f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs presented by Sweet and Bumpass (1987).<br />

PREVIOUS RESEARCH<br />

Unfortunately, much previous research has been constra<strong>in</strong>ed by the use of data, such as<br />

the National Longitud<strong>in</strong>al Survey of Youth or the National Longitud<strong>in</strong>al Study of the <strong>High</strong><br />

School Class of 1972, that have provided limited <strong>in</strong>formation about divorce across historical<br />

time (Becker et al. 1977; Booth and Edwards 1985; Bumpass and Sweet 1972;<br />

South and Lloyd 1995; South and Spitze 1986; Teachman 1986; Teachman and Polonko<br />

1990). In other <strong>in</strong>stances, when data, such as the Current Population Survey, conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on divorce across a broader range of historical time have been utilized, it has<br />

been common for researchers to account for historical shifts <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce by<br />

simply add<strong>in</strong>g a control for marriage cohort (or some other <strong>in</strong>dicator of historical time) <strong>in</strong><br />

their models (Bumpass, Mart<strong>in</strong>, and Sweet 1991; Heaton 1991; Lehrer and Chiswick 1993;<br />

Waite and Lillard 1991). The implicit assumption has been that any historical change <strong>in</strong><br />

the risk of divorce affects all marriages equally.<br />

Carlson and St<strong>in</strong>son (1982) conducted one of the first studies to f<strong>in</strong>d that the effects of<br />

one or more predictors of divorce may not be stable across time. They found that the<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> marital dissolution across time was the greatest among women who married as<br />

teenagers. However, three other studies (Mart<strong>in</strong> and Bumpass 1989; Morgan and R<strong>in</strong>dfuss<br />

1985; Thornton and Rodgers 1987) have failed to replicate this f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Mart<strong>in</strong> and Bumpass (1989) reported an <strong>in</strong>teraction between marriage cohort and both<br />

education and premarital fertility. Specifically, women with more education were <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

less likely to divorce, and women with children who were born before marriage were<br />

first less and then more likely to divorce. Other research has found some evidence to<br />

suggest that the effects of premarital cohabitation (Schoen 1992), parental divorce<br />

(Wolf<strong>in</strong>ger 1999), and race (Sweet and Bumpass 1987) have effects that vary across time.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, <strong>in</strong> the most recent effort to identify effects that vary across time, South (2001)<br />

found that the impact of wives’ employment on divorce has <strong>in</strong>creased over the past 25<br />

years (although the effect of wives’ education has not changed).<br />

Overall, the empirical evidence is limited but suggests that some covariates may have<br />

effects on divorce that vary over time. The number of studies that have explicitly considered<br />

this possibility rema<strong>in</strong>s small, however. Moreover, these studies have tended to focus<br />

on a s<strong>in</strong>gle covariate of divorce and generally have been restricted to a consideration of<br />

marriages that were formed after 1959. I extend previous research by consider<strong>in</strong>g both a<br />

wider range of time and a wide range of covariates.<br />

DATA AND METHODS<br />

Data<br />

The data for this study were taken from the five rounds of the NSFG, conducted <strong>in</strong> 1973,<br />

1976, 1982, 1988, and 1995 (National Center for Health Statistics 1998). The first two

334 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

rounds of the NSFG were nationally representative samples of women aged 15–44 who<br />

were ever married or who had a child of their own liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the household. The last three<br />

rounds were nationally representative samples of all women aged 15–44. The sample sizes<br />

were 9,797 for round 1; 8,611 for round 2; 7,969 for round 3; 8,450 for round 4; and<br />

10,847 for round 5.<br />

Each round of the NSFG obta<strong>in</strong>ed retrospective <strong>in</strong>formation about the marital history<br />

of all the respondents. I used this <strong>in</strong>formation to calculate the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and end<strong>in</strong>g dates<br />

of all first marriages. I selected all first marriages that were formed between 1950 and<br />

1984, yield<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation on divorces that occurred between 1950 and 1995. Over this<br />

period, there were substantial shifts <strong>in</strong> age at marriage, marital dissolution, education,<br />

out-of-wedlock childbear<strong>in</strong>g, premarital cohabitation, and divorce.<br />

Marriages formed before 1950 were excluded because they <strong>in</strong>cluded only women who<br />

married prior to age 21. I excluded marriages formed after 1984 to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on<br />

at least 10 years of potential exposure to the risk of divorce for all marriages. Of course,<br />

earlier marriage cohorts have much longer potential marital durations. In results not reported<br />

here, however, my conclusions were not affected by the arbitrary truncation of all<br />

marriages after 10 years of exposure to the risk of divorce. 1 After I selected first marriages<br />

formed between 1950 and 1984, there were 27,296 marriages (7,611 divorces)<br />

available for analysis.<br />

Each round of the NSFG collected retrospective marital histories <strong>in</strong> a consistent fashion,<br />

limit<strong>in</strong>g the possibility that changes <strong>in</strong> the risk of marital dissolution across time are<br />

artifacts of the survey design. It is possible, though, that some historical differences <strong>in</strong><br />

marital dissolution are due to differences <strong>in</strong> samples and collection procedures. To m<strong>in</strong>imize<br />

this possibility, I constructed a set of dummy variables <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g the survey round<br />

from which each respondent’s data were taken. I estimated all models with these dummy<br />

variables <strong>in</strong>cluded to provide protection aga<strong>in</strong>st survey-specific effects.<br />

Each round of the NSFG also collected different types of background <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

that can be used to predict divorce. However, there is a set of basic sociodemographic<br />

predictors available <strong>in</strong> all five rounds. These predictors are all fixed at the time of marriage<br />

and <strong>in</strong>clude wife’s age at marriage, husband’s age at marriage, education of the<br />

wife, education of the husband, premarital fertility status, parental divorce status, religion,<br />

and race. 2 From this set of variables, it is also possible to calculate estimates of the<br />

age homogamy and educational homogamy of the spouses. Although this is a somewhat<br />

limited set of predictor variables, it represents a broader array of covariates that could<br />

<strong>in</strong>teract with historical time than has hitherto been considered.<br />

To simplify the analysis, I did not consider time-vary<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation on marital births.<br />

Although marital fertility has been l<strong>in</strong>ked to the risk of divorce (Morgan and R<strong>in</strong>dfuss<br />

1985; South and Spitze 1986; Waite and Lillard 1991), childbear<strong>in</strong>g decisions are not<br />

fixed at the time of marriage. Because children can be born at any marital duration and<br />

their effects on marital dissolution vary accord<strong>in</strong>g to their age and number (Waite and<br />

Lillard 1991), isolat<strong>in</strong>g the effects of marital childbear<strong>in</strong>g as they vary accord<strong>in</strong>g to marital<br />

duration and historical period is not straightforward. It rema<strong>in</strong>s the task of a subsequent<br />

research project to tackle this problem.<br />

1. I truncated all marriages at 10 years’ duration by cod<strong>in</strong>g marriages of longer duration as be<strong>in</strong>g censored<br />

at that po<strong>in</strong>t. I then reestimated each of the event-history models described later, and found no substantive<br />

differences.<br />

2. In most cases, these predictor variables were measured consistently across rounds of the NSFG. However,<br />

there are a few differences <strong>in</strong> measurement that should be noted. Parental divorce status was measured at<br />

age 14 for the respondent <strong>in</strong> the first four rounds (Was the respondent not liv<strong>in</strong>g with both biological parents<br />

because of divorce?) but us<strong>in</strong>g a full parent history <strong>in</strong> round 5 (I used this parent history to code whether the<br />

respondent was not liv<strong>in</strong>g with both parents at age 14 because of divorce). Wife’s education was measured at the<br />

time of marriage <strong>in</strong> rounds 1, 2, and 4 and the highest level atta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> rounds 3 and 5. Husband’s education was<br />

measured at marriage <strong>in</strong> all rounds except round 3, when it was measured as the highest level obta<strong>in</strong>ed.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 335<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, rounds 4 and 5 of the NSFG conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation on premarital cohabitation<br />

status. This <strong>in</strong>formation allows a more limited test of the possibility that the effect of<br />

premarital cohabitation has changed across time us<strong>in</strong>g marriages formed after 1969. The<br />

availability of this <strong>in</strong>formation also allows a consideration of the possibility that the effects<br />

of the other predictor variables are confounded with premarital cohabitation.<br />

Methods<br />

I exam<strong>in</strong>ed the effects of the measured covariates on divorce us<strong>in</strong>g a Cox proportional<br />

hazards model (Cox 1972). Completed spells of marriage were measured by the duration<br />

<strong>in</strong> months between the date of marriage and the date of separation. Censored spells were<br />

measured <strong>in</strong> months between the date of marriage and the date of the survey or between<br />

the date of marriage and the date of death of the spouse for the small number of widowed<br />

women <strong>in</strong> the NSFG. The Cox model takes the follow<strong>in</strong>g form:<br />

h(t) = λ 0(t)exp(Xβ),<br />

where h(t) is the hazard of divorce at marital duration t, λ 0(t) is an unspecified basel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

hazard rate at marital duration t that is shifted upward or downward by the vector of<br />

measured covariates X <strong>in</strong> amounts equivalent to exp(β). The Cox model is easy to fit to<br />

the data and requires no assumptions about the shape of the hazard rate as it varies accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to marital duration.<br />

To measure the effects of historical context, I <strong>in</strong>cluded an <strong>in</strong>dicator of the year <strong>in</strong><br />

which each respondent was first married. Without further consideration, this measure<br />

may be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as the effect of either the marriage cohort or the historical period.<br />

Either <strong>in</strong>terpretation is possible because the historical period is equal to the effect of the<br />

marriage cohort (the year <strong>in</strong> which the respondent was first married) plus marital duration,<br />

and, as estimated, the Cox model allows the risk of divorce to vary simultaneously<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>g to the year of marriage and marital duration. As described by Allison (1995:<br />

142–43), the effect of historical time is perfectly captured by the coefficient for year<br />

married.<br />

The question becomes: should the effect of time, as <strong>in</strong>dicated by the coefficient for<br />

year married, be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as the effect of historical period or marriage cohort? On the<br />

basis of the results provided by Thornton and Rodgers (1987), I <strong>in</strong>terpreted the coefficient<br />

for year of marriage <strong>in</strong> terms of the effect of historical period and assumed that the<br />

effects of cohort (either marriage cohort or birth cohort) on divorce are m<strong>in</strong>imal. I conducted<br />

several tests to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether this was a reasonable assumption and found no<br />

evidence to suggest that it was not. 3<br />

3. First, follow<strong>in</strong>g Thornton and Rodgers (1987), I plotted the risk of marital dissolution for two marital<br />

durations (the first 18 months of marriage and months 54–72) across marriage cohorts. If marriage cohort and<br />

marital duration act additively to <strong>in</strong>fluence the risk of marital dissolution (i.e., there is no effect of historical<br />

period), the ratio of the risks at the two marital durations should be constant across marriage cohorts. That is not<br />

the pattern that was observed (results not shown). Rather, the ratio of the two risks <strong>in</strong>dicated first divergence and<br />

then convergence. Without consider<strong>in</strong>g an effect of historical period, the only way that this pattern could be<br />

observed would be if one assumed a strong <strong>in</strong>teraction between marriage cohort and marital duration. Second,<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g the work of Ono (1999), I estimated a model with effects for year of marriage (to measure historical<br />

period) plus an <strong>in</strong>dicator specific to marriage cohort (average age at first marriage for wives for the year <strong>in</strong><br />

which the respondent was married). Contrary to Ono’s f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, this model did not <strong>in</strong>dicate an <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

effect of marriage cohort. F<strong>in</strong>ally, I estimated a model that <strong>in</strong>cluded effects for year of marriage (historical<br />

period) plus an <strong>in</strong>dicator specific to birth cohort (gross domestic product for the year <strong>in</strong> which the respondent<br />

was born). This model failed to provide any evidence for the effects of birth cohort. Of course, these results rely<br />

on the choice of <strong>in</strong>dicators for either marriage cohort or birth cohort. Different results could hold if alternative<br />

measures of these cohort effects were constructed.

336 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS<br />

Age at marriage for both husbands and wives was coded <strong>in</strong> years; education was coded <strong>in</strong><br />

years of completed school<strong>in</strong>g; premarital birth was coded 1 for women who entered the<br />

first marriage with a birth, 0 otherwise; premarital conception was coded 1 for women<br />

who gave birth to a child with<strong>in</strong> the first seven months of marriage, 0 otherwise; wife<br />

older was coded 1 when the woman was two or more years older than her husband, 0<br />

otherwise; husband older was coded 1 when the husband was five or more years older<br />

than his wife, 0 otherwise; wife has more education was coded 1 if the wife had at least a<br />

high school degree and at least two years of school<strong>in</strong>g more than her husband, 0 otherwise;<br />

parents divorced was coded 1 if the woman was not liv<strong>in</strong>g with both biological<br />

parents at age 14 because of divorce, 0 otherwise; Catholic was coded 1 for women who<br />

reported be<strong>in</strong>g Catholic, 0 otherwise; black was coded 1 for women who reported they<br />

are black, 0 otherwise; and other race was coded 1 for women who did not report their<br />

race as either white or black.<br />

Each of these predictor variables has received considerable attention <strong>in</strong> the literature<br />

(see the reviews <strong>in</strong> DaVanzo and Rahman 1993; Faust and McKibben 1999; Teachman,<br />

Tedrow, and Crowder 2000; White 1990), and I did not develop separate rationales for<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> the analysis. In general, it has been found that the risk of divorce decl<strong>in</strong>es<br />

with <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> age at marriage and education. <strong>Divorce</strong> is also less likely among<br />

Catholics and whites, <strong>in</strong> age- and educationally homogeneous marriages, and <strong>in</strong> marriages<br />

not preceded by a birth or conception or a parental divorce.<br />

Although the sample is large, the number of divorces that occurred for women who<br />

were married <strong>in</strong> a given year was small. Thus, the number of divorces accord<strong>in</strong>g to a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle year of marriage showed substantial random fluctuation. To alleviate this problem,<br />

I grouped marriages <strong>in</strong>to five-year cohorts: 1950–1954, 1955–1959, 1960–1964, 1965–<br />

1969, 1970–1974, 1975–1979, and 1980–1984. I calculated a cont<strong>in</strong>uous measure for year<br />

of marriage by cod<strong>in</strong>g 1 for marriages formed <strong>in</strong> 1950–1954, 2 for marriages formed <strong>in</strong><br />

1955–1959, and so forth to 7 for marriages formed <strong>in</strong> 1980–1984. This is the measure of<br />

year of marriage used <strong>in</strong> all the models.<br />

All results are shown us<strong>in</strong>g unweighted data. I do not provide descriptive statistics<br />

based on weighted data because I know a priori that the distributions of the predictor<br />

variables by marriage cohort are not nationally representative of each cohort. The purpose<br />

of this article is not to document accurately changes across marriage cohorts <strong>in</strong> their<br />

composition but, rather, to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether the effects of important predictor variables<br />

change across time. As I describe later, I conducted a number of sensitivity tests to ascerta<strong>in</strong><br />

the robustness of my results. F<strong>in</strong>ally, results from the Cox proportional hazards models<br />

are shown as a function of the unweighted data to preserve the appropriate calculation<br />

of standard errors. 4<br />

Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown <strong>in</strong> Table 1. Although the results are<br />

biased by the fact that age at marriage is truncated <strong>in</strong> early marriage cohorts, they are<br />

consistent with previous research. In particular, age at marriage and education have<br />

shifted upward for both husbands and wives. In addition, more marriages are preceded<br />

by a premarital birth, and more women come from families that are disrupted by divorce.<br />

There is also some <strong>in</strong>dication that heterogeneity <strong>in</strong> marriage has shifted toward more<br />

women be<strong>in</strong>g older and hav<strong>in</strong>g more education than their husbands. Variations <strong>in</strong> racial<br />

composition and religion are more difficult to <strong>in</strong>terpret but likely reflect the overall retreat<br />

from marriage by blacks and the rapid <strong>in</strong>crease of the Hispanic population <strong>in</strong> the<br />

United States. As a result, blacks constitute a smaller share of all marriages, and there<br />

4. In results not shown here, the coefficients estimated from weighted data were not substantially different<br />

from those estimated from unweighted data.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 337<br />

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample of Marriages Taken From Five Rounds of the National<br />

Survey of Family Growth<br />

_________________________________________________________________________<br />

Year Married<br />

Variable 1950– 1955– 1960– 1965– 1970– 1975– 1980–<br />

Age at Marriage<br />

1954 1959 1964 1969 1974 1979 1984<br />

< 19 51.6 42.3 39.3 33.7 33.2 24.3 18.9<br />

20–21 29.5 26.9 27.6 28.9 29.0 26.1 21.7<br />

22–23 14.3 17.6 17.7 19.8 19.4 21.9 20.5<br />

24–25 4.1 8.2 7.5 8.9 9.3 14.0 15.2<br />

25+<br />

Husband’s Age at<br />

Marriage<br />

0.4 5.0 7.9 8.6 9.1 13.9 23.8<br />

< 19 13.7 11.1 11.2 10.9 10.9 8.8 6.2<br />

20–21 24.8 22.2 22.2 21.8 22.2 17.6 14.9<br />

22–23 22.7 24.4 24.5 25.2 24.6 21.5 17.3<br />

24–25 17.0 17.0 15.6 16.8 16.9 18.8 17.3<br />

25+<br />

Woman’s Education<br />

21.9 25.3 26.5 25.2 25.4 33.3 44.2<br />

< 12 years 45.0 37.8 34.7 25.7 23.1 16.1 16.5<br />

12 years 42.7 44.7 44.7 46.1 43.8 40.7 38.2<br />

13–15 years 10.1 11.7 13.8 18.1 20.1 24.4 25.7<br />

16+ years<br />

Husband’s Education<br />

2.2 5.9 6.7 10.0 12.9 18.5 19.5<br />

< 12 years 45.0 37.9 32.3 24.1 19.7 16.8 18.0<br />

12 years 30.9 35.3 36.8 39.4 40.8 42.9 43.2<br />

13–15 years 12.1 11.6 13.9 17.4 20.5 20.7 19.1<br />

16+ years<br />

Premarital Fertility<br />

11.1 14.0 15.4 17.8 17.7 18.0 18.6<br />

Birth 7.2 10.6 11.9 12.6 13.2 14.8 18.9<br />

Conception 10.1 11.8 13.2 13.5 12.9 10.0 10.2<br />

Wife Older 1.5 2.6 2.7 2.7 4.0 5.5 6.0<br />

Husband Older<br />

Wife Has More<br />

26.2 23.1 22.4 17.7 17.7 19.6 22.7<br />

Education 13.8 13.8 13.0 13.5 13.8 19.9 20.7<br />

Parents <strong>Divorce</strong>d 8.8 8.8 10.1 10.7 11.3 13.2 17.4<br />

Catholic<br />

Race<br />

21.3 21.5 22.8 23.1 24.8 28.6 30.9<br />

White 69.3 67.1 66.9 67.0 68.9 72.7 72.3<br />

Black 30.2 32.1 32.1 31.5 28.9 23.8 23.3<br />

Other 0.5 0.8 1.0 1.3 2.2 3.4 4.2<br />

N 1,962 2,901 3,857 5,545 6,481 3,345 3,205

338 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

has been a rise <strong>in</strong> the proportion of marriages <strong>in</strong> which the wife reports that she is Catholic.<br />

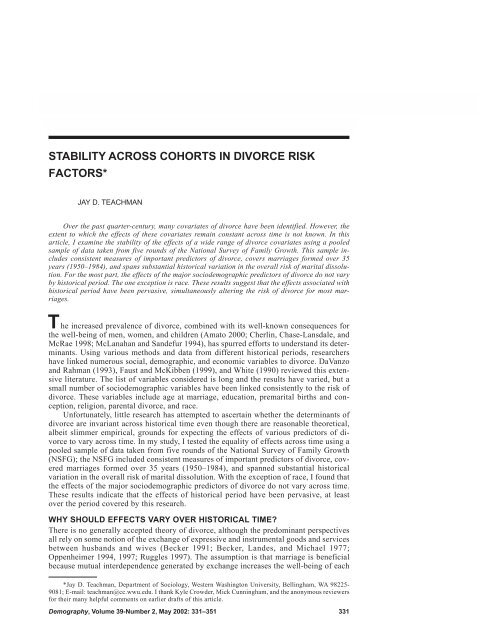

Change <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce over time is represented <strong>in</strong> Figure 1, where the yearly<br />

proportion of marriages surviv<strong>in</strong>g divorce is plotted for the first 10 years of marriage. The<br />

figure replicates the well-known rise <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce that occurred <strong>in</strong> the 1960s and<br />

1970s and the slow<strong>in</strong>g of this rise <strong>in</strong> the 1980s. The change <strong>in</strong> rates of divorce has been<br />

substantial. In the 1950–1954 cohort, almost 85% of marriages survived at least 10 years,<br />

whereas <strong>in</strong> the last three cohorts, only about 70% of marriages survived at least 10 years.<br />

MULTIVARIATE RESULTS<br />

I first ascerta<strong>in</strong>ed whether the effects of the cont<strong>in</strong>uous variables—age at marriage,<br />

husband’s age at marriage, marriage cohort, and education of husbands and wives—were<br />

best represented with a cont<strong>in</strong>uous cod<strong>in</strong>g or a set of dummy variables. I started by<br />

construct<strong>in</strong>g a set of dummy variables for these variables us<strong>in</strong>g the categories presented<br />

<strong>in</strong> Table 1. For each of the variables, I then estimated a simple Cox regression model<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g the dummy-variable cod<strong>in</strong>g and compared the results with two alternative Cox<br />

models us<strong>in</strong>g the variable coded cont<strong>in</strong>uously: a model with only a l<strong>in</strong>ear term and a<br />

model with both a l<strong>in</strong>ear and quadratic term. I compared models us<strong>in</strong>g both the traditional<br />

log-likelihood ratio (LR) statistic and Raftery’s (1995) Bayesian <strong>in</strong>formation criterion<br />

(BIC) statistic. 5<br />

In results not shown, I ascerta<strong>in</strong>ed that the best-fitt<strong>in</strong>g models were those that used a<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ear and a quadratic term for age at marriage, husband’s age at marriage, and marriage<br />

cohort and a l<strong>in</strong>ear term for wife’s education (based on both the LR and BIC statistics).<br />

For husband’s education, the dummy variables represented a better fit to the data. An<br />

additional analysis <strong>in</strong>dicated that a dummy variable with three categories for husband’s<br />

education fit the data best: 12 or fewer years, 13–15 years, and 16 or more years. These<br />

are the revised cod<strong>in</strong>gs for the variables that I used <strong>in</strong> the multivariate analysis.<br />

I began with a basel<strong>in</strong>e model that <strong>in</strong>cludes the additive effect of each variable (Model<br />

A <strong>in</strong> Table 2). Based on the weight of prior evidence, the basel<strong>in</strong>e model represents a<br />

reasonable specification of the effects of the covariates on the risk of divorce. I then tested<br />

a series of models aga<strong>in</strong>st this basel<strong>in</strong>e model. Each additional model, except the last,<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes an <strong>in</strong>teraction between an <strong>in</strong>dividual predictor variable and historical time (as<br />

measured by year of marriage). For example, Model B adds an <strong>in</strong>teraction term between<br />

age at marriage and year of marriage to the basel<strong>in</strong>e model. Model C then adds an <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

term between hav<strong>in</strong>g a premarital birth and year of marriage to the basel<strong>in</strong>e model,<br />

and so on. The last model, Model N, <strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>in</strong>teractions between all the predictor variables<br />

and year of marriage.<br />

Each model with an <strong>in</strong>teraction term was compared with the basel<strong>in</strong>e model via differences<br />

<strong>in</strong> the LR and BIC statistics. Although both statistics are presented, I placed<br />

greater weight on the difference between the BIC statistics to test whether the null hypothesis<br />

of no <strong>in</strong>teraction should be rejected. I did so because it is well known that conventional<br />

test statistics are <strong>in</strong>fluenced by sample size. Thus, <strong>in</strong> reasonably large samples,<br />

such as the one used <strong>in</strong> this article, it is difficult to reject poor-fitt<strong>in</strong>g models us<strong>in</strong>g the LR<br />

statistic. More important, substantively un<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g differences between models will be<br />

judged to be statistically significant when sample sizes are large. Thus, even if the basel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

model is appropriate, use of the LR statistic, <strong>in</strong> conjunction with a large sample, may<br />

5. The BIC statistic is calculated as –χ 2 + df × ln(n), where χ 2 is the model chi-square, df is the degrees of<br />

freedom associated with the model, and n is the number of events (divorces) upon which the model is based.<br />

Note that I use the number of divorces as the value of n, not the number of marriages, yield<strong>in</strong>g a less conservative<br />

version of BIC. Models with more negative values of BIC are preferred to models with less negative values<br />

of BIC. A spirited discussion of the value of BIC as a tool for model selection is provided by Weakliem (1999)<br />

and the comments to his article <strong>in</strong> the same issue of Sociological Methods and Research.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 339<br />

Figure 1. Proportion of Marriages Not Disrupted, by Marriage Cohort<br />

Proportion<br />

1<br />

0.95<br />

0.9<br />

0.85<br />

0.8<br />

0.75<br />

0.7<br />

0.65<br />

1950–1954<br />

1955–1959<br />

1960–1964<br />

1965–1969<br />

1970–1974<br />

1975–1979<br />

1980–1984<br />

0.6<br />

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

Marital Duration <strong>in</strong> Years<br />

lead to <strong>in</strong>appropriate conclusions—<strong>in</strong> this case, to <strong>in</strong>appropriately reject the null hypothesis<br />

of simple additive effects <strong>in</strong> favor of <strong>in</strong>teraction effects.<br />

The BIC statistic operates by penaliz<strong>in</strong>g models when they add degrees of freedom<br />

or sample size. The procedure is therefore conceptually equivalent to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the size<br />

of a t statistic that is required to reject a null hypothesis for a s<strong>in</strong>gle coefficient. Although<br />

there are no formal cutoffs for assess<strong>in</strong>g the importance of a difference between<br />

two BIC values, Raftery (1995) provided the follow<strong>in</strong>g guidel<strong>in</strong>es. If there is a difference<br />

of 10 or more between two BIC values, there is very strong evidence that the null<br />

model should be rejected. Differences between BIC values of 6–10, 2–6, and 0–2 <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

strong, positive, and weak evidence, respectively, that the null model should be<br />

rejected. In the case of comparisons <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g one degree of freedom (e.g., Models B<br />

through M <strong>in</strong> Table 2) and the number of divorces <strong>in</strong> this sample, these values of BIC<br />

correspond to t values of 3.86–4.35, 3.31–3.86, 2.99–3.31, respectively (squar<strong>in</strong>g these<br />

values yields the correspond<strong>in</strong>g chi-square values with 1 degree of freedom). Thus, the<br />

effect of us<strong>in</strong>g BIC is simply to require stronger evidence before the null hypothesis of<br />

no <strong>in</strong>teraction with time is rejected.<br />

Differences <strong>in</strong> LR statistics that are significant at p < .05 are presented <strong>in</strong> italic type.<br />

Differences <strong>in</strong> BIC statistics that <strong>in</strong>dicate at least positive support for reject<strong>in</strong>g the null<br />

hypothesis (< –2.0) are presented <strong>in</strong> bold italic type. On the basis of values of the conventional<br />

LR test statistic, significant <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong>volve the husband’s age at marriage and

340 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

Table 2. Estimates of Model Fit for Models Involv<strong>in</strong>g an Interaction Between Each Predictor<br />

Variable and Year Married<br />

Model χ 2 / df BIC<br />

Model Model χ 2 df Difference BIC Difference<br />

A: Basel<strong>in</strong>e Additive Model 2,929.58 22 –– –2,732.96 ––<br />

B: A + Age at Marriage × Year Married<br />

C: A + Husband’s Age at Marriage × Year<br />

2,933.14 23 3.56/1 –2,727.58 5.38<br />

Married 2,938.39 23 8.81/1 –2,732.83 0.13<br />

D: A + Premarital Birth × Year Married 2,933.14 23 3.56/1 –2,727.58 5.38<br />

E: A + Premarital Conception × Year Married 2,929.80 23 0.22/1 –2,724.24 8.72<br />

F: A + Wife Older × Year Married<br />

G: A + Wife Has More Education × Year<br />

2,930.51 23 0.93/1 –2,724.95 8.01<br />

Married 2,931.93 23 2.35/1 –2,726.37 6.59<br />

H: A + Husband Older × Year Married 2,939.01 23 9.43/1 –2,733.45 –0.49<br />

I: A + Wife’s Education × Year Married 2,932.22 23 2.64/1 –2,726.66 6.30<br />

J: A + Husband’s Education × Year Married 2,929.89 24 0.31/2 –2,715.40 17.56<br />

K: A + Catholic × Year Married 2,936.00 23 6.42/1 –2,731.44 1.52<br />

L: A + Wife’s Parents <strong>Divorce</strong>d × Year Married 2,931.14 23 1.56/1 –2,725.58 7.38<br />

M: A + Black × Year Married 2,953.24 23 23.66/1 –2,747.68 –14.72<br />

N: A + All Interactions With Year Married 2,980.33 35 50.75/13 –2,667.52 65.44<br />

Notes: All models <strong>in</strong>clude a control for survey round. N for the calculation of BIC is 7,611. Values <strong>in</strong> italic type are<br />

statistically significant at p < .05. Values <strong>in</strong> bold italic type show strong evidence us<strong>in</strong>g BIC for reject<strong>in</strong>g the null hypothesis of a<br />

zero effect.<br />

the husband be<strong>in</strong>g older, be<strong>in</strong>g Catholic, and be<strong>in</strong>g black. However, the BIC statistic <strong>in</strong>dicates<br />

only one <strong>in</strong>teraction with positive evidence that the null hypothesis of no change<br />

across time should be rejected: the effect of be<strong>in</strong>g black.<br />

The results for Model N, which simultaneously <strong>in</strong>cludes all <strong>in</strong>teractions with historical<br />

time, <strong>in</strong>dicate a significantly better-fitt<strong>in</strong>g model us<strong>in</strong>g the LR statistic but not the<br />

BIC statistic. Indeed, the substantial <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the BIC statistic <strong>in</strong>dicates that this model<br />

may be overparameterized (i.e., may conta<strong>in</strong> too many nonsignificant parameters). The<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual coefficients from this model, however, are <strong>in</strong>structive: they <strong>in</strong>dicate that when<br />

all <strong>in</strong>teractions are considered simultaneously, the only significant <strong>in</strong>teraction, us<strong>in</strong>g either<br />

the LR or BIC statistic as the criterion, is that associated with be<strong>in</strong>g black (results<br />

not shown). This result provides further support for the notion that the only substantial<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction with time <strong>in</strong>volves blacks.<br />

Hazard ratios from bivariate Cox regression models, the additive multivariate basel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

model (Model A <strong>in</strong> Table 2), and the model <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>teraction between year of<br />

marriage and be<strong>in</strong>g black (Model M <strong>in</strong> Table 2) are shown <strong>in</strong> Table 3. The hazard ratios<br />

shown (e β ) represent multiplicative effects on the hazard of marital dissolution at any<br />

marital duration. Hazard ratios greater than 1 <strong>in</strong>dicate a positive effect, and hazard ratios<br />

less than 1 <strong>in</strong>dicate a negative effect. The percentage difference <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce at<br />

any marital duration associated with a unit change <strong>in</strong> a predictor variable can be calculated<br />

by subtract<strong>in</strong>g 1 from the hazard ratio and multiply<strong>in</strong>g by 100.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 341<br />

Table 3. Hazard Ratios From Selected Models <strong>in</strong> Table 2<br />

Bivariate Model Additive Model Interaction Model<br />

Variable Coefficients Coefficients Coefficients<br />

Year Married 1.38 1.41 1.46<br />

Year Married, Squared 0.97 0.98 0.98<br />

Age at Marriage 0.63 0.70 0.70<br />

Age at Marriage Squared 1.01 1.01 1.01<br />

Husband’s Age at Marriage 0.82 0.92 0.92<br />

Husband’s Age at Marriage, Squared 1.003 1.001 1.001<br />

Premarital Birth 2.08 1.68 1.69<br />

Premarital Conception 1.41 1.16 1.15<br />

Wife Older 1.48 1.68 1.88<br />

Wife Has More Education 1.17 1.10a 1.09a Husband Older 1.14 1.19 1.19<br />

Wife’s Education 0.94 1.04 1.05<br />

Husband Has 13–15 Years of School<strong>in</strong>g 0.59 0.69 0.69<br />

Husband Has 16+ Years of School<strong>in</strong>g 0.39 0.56 0.55<br />

Catholic 0.69 0.90 0.89<br />

Wife’s Parents <strong>Divorce</strong>d 1.64 1.39 1.38<br />

Black 1.99 1.49 1.97<br />

Black × Year Married –– –– 0.93<br />

Other Race 0.90b 0.95b 0.93b Note: All models <strong>in</strong>clude a control for survey round.<br />

a<br />

The null hypothesis that the coefficient is not statistically significant cannot be rejected us<strong>in</strong>g a BIC value equal to strong<br />

evidence (t > 3.31).<br />

b The coefficient is not statistically significant at the conventional .05 level.<br />

The hazard ratios for year of marriage and age at marriage are consistent across all<br />

three models. The coefficients for year of marriage <strong>in</strong>dicate an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g risk of marital<br />

dissolution that has slackened <strong>in</strong> pace more recently. 6 The hazard ratios for each<br />

spouse’s age at marriage reflect a decrement <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce with age that moderates<br />

somewhat at older ages (although the pattern of change across age at marriage is<br />

stronger for wives than husbands).<br />

The effects of both a premarital birth and a premarital conception on divorce are<br />

positive, with the effect of a premarital birth be<strong>in</strong>g much stronger. In both cases, the<br />

multivariate models show effects that are somewhat lower than <strong>in</strong> the bivariate model.<br />

That is, a nontrivial portion of the effect of both variables can be attributed to other<br />

covariates <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the model.<br />

6. For the sake of parsimony, I use the phrase “<strong>in</strong>crease or decrease <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce” when the<br />

correct phrase is “<strong>in</strong>crease or decrease <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce at a given marital duration.”

342 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

The effect of the husband be<strong>in</strong>g older on divorce is positive <strong>in</strong> both the bivariate and<br />

additive effect models. The effect of the wife be<strong>in</strong>g older is substantial. In the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

effect model, if a wife is five or more years older than her husband, the risk of divorce is<br />

88% higher <strong>in</strong> comparison with a marriage that has relative age homogamy. The effect of<br />

the wife hav<strong>in</strong>g more education is also positive, although not significant us<strong>in</strong>g the BIC<br />

criterion for strong evidence, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the risk of divorce by 9% at each marital duration.<br />

The effect of the wife’s education is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> that it reverses direction between<br />

the bivariate model and the two multivariate models. In the bivariate model, the risk of<br />

marital disruption decreases 6% for each additional year of school<strong>in</strong>g the wife has. In the<br />

multivariate models, the risk of divorce <strong>in</strong>creases 4%–5% for each additional year of the<br />

wife’s school<strong>in</strong>g. The switch from a negative to a positive effect is due mostly to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusion of the control for husband’s education (results not shown). More-educated<br />

women are generally married to more-educated men, and the effect of the husband’s education<br />

is substantial and negative.<br />

The effect of be<strong>in</strong>g Catholic is to reduce the risk of marital dissolution, and the effect<br />

of the wife’s parents hav<strong>in</strong>g divorced is positive. In both cases, though, the effect is reduced<br />

somewhat with the <strong>in</strong>troduction of the other covariates. In the <strong>in</strong>teraction model, at<br />

each marital duration, Catholics are 11% less likely to divorce, and couples <strong>in</strong> which the<br />

wives’ parents divorced are 38% more likely to divorce.<br />

There is no difference between whites and respondents report<strong>in</strong>g neither white nor<br />

black race <strong>in</strong> the risk of marital dissolution. Blacks are substantially more likely to divorce<br />

at each marital duration than are whites. However, this effect changes across time.<br />

In the 1950–1954 cohort, the risk of divorce for blacks is 83% greater (1.97 × .93 = 1.83).<br />

In the 1980–1984 cohort, the risk of marital dissolution for blacks is only 19% higher.<br />

This pattern results from the fact that the risk of marital dissolution <strong>in</strong>creases more slowly<br />

(by a factor of .93) for blacks than for whites.<br />

A Test for Proportionality<br />

All the models estimated up to this po<strong>in</strong>t assume that the effects of the covariates are<br />

proportional. That is, the effects of the predictor variables are assumed to be equal at all<br />

marital durations. A test for proportionality is key for the purposes of this study to account<br />

for the possibility that historical shifts <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce may be confused with<br />

nonproportionality. In particular, a variable with an effect that <strong>in</strong>creases (decreases) with<br />

marital duration may be mistaken for a variable with an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g (decreas<strong>in</strong>g) effect<br />

across historical time.<br />

In general, two rationales have been put forward to suspect nonproportionality. First,<br />

as marriages mature, <strong>in</strong>dividuals accrue more marital-specific capital (Becker et al.<br />

1977), decreas<strong>in</strong>g the risk of divorce. Thus, <strong>in</strong>dividual couples change with respect to<br />

their risk of marital disruption. Second, as marriages progress, a process of sort<strong>in</strong>g occurs,<br />

weed<strong>in</strong>g out couples who are less suited to each other or less committed to a permanent<br />

relationship (Morgan and R<strong>in</strong>dfuss 1985; South and Spitze 1986; Teachman<br />

1986). The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g marriages are therefore composed of couples who are less likely to<br />

divorce.<br />

The empirical evidence is limited, but a number of researchers, us<strong>in</strong>g different data<br />

and methods, have found that the effect of age at marriage is stable across marital duration<br />

(Morgan and R<strong>in</strong>dfuss 1985; South and Spitze 1986; Teachman 1986; Thornton and<br />

Rodgers 1987). Morgan and R<strong>in</strong>dfuss (1985) reported that the positive effect on divorce<br />

of hav<strong>in</strong>g a premarital birth decl<strong>in</strong>es at longer marital durations, but Teachman (1986)<br />

found a more consistent effect for this variable. South and Spitze (1986) and South (2001)<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicated that the effect of the wife’s education changes from be<strong>in</strong>g negative to be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

positive as marriages mature. Aga<strong>in</strong>, however, Teachman (1986) found a consistent effect<br />

of the wife’s education across different marital durations.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 343<br />

Table 4. Tests for the Proportionality of Each of the Predictor Variables<br />

Model χ 2 / df BIC<br />

Model Model χ 2 df Difference BIC Difference<br />

A: Basel<strong>in</strong>e Proportional Effects Model 2,929.58 22 –2,732.97 ––<br />

B: A + Age at Marriage × Marital Duration<br />

C: A + Husband’s Age at Marriage × Marital<br />

2,930.21 23 0.60/1 –2,724.65 8.32<br />

Duration 2,930.57 23 0.99/1 –2,725.01 7.96<br />

D: A + Premarital Birth × Marital Duration<br />

E: A + Premarital Conception × Marital<br />

2,935.64 23 6.06/1 –2,730.08 2.89<br />

Duration 2,930.31 23 0.73/1 –2,724.75 8.22<br />

F: A + Wife Older × Marital Duration<br />

G: A + Wife Has More Education × Marital<br />

2,933.91 23 4.33/1 –2,728.35 4.62<br />

Duration 2,929.60 23 0.02/1 –2,724.04 8.93<br />

H: A + Husband Older × Marital Duration 2,932.11 23 2.53/1 –2,726.55 6.42<br />

I: A + Wife’s Education × Marital Duration 2,935.27 23 5.69/1 –2,729.71 3.26<br />

J: A + Husband’s Education × Marital Duration 2,947.91 24 18.33/2 –2,733.41 –0.44<br />

K: A + Catholic × Marital Duration<br />

L: A + Wife’s Parents <strong>Divorce</strong>d × Marital<br />

2,929.89 23 0.31/1 –2,724.33 8.64<br />

Duration 2,934.39 23 4.81/1 –2,728.83 4.14<br />

M: A + Black × Marital Duration 2,934.96 23 5.38/1 –2,729.40 3.57<br />

Notes: All models <strong>in</strong>clude a control for survey round. N for calculat<strong>in</strong>g BIC is 7,611. Values <strong>in</strong> italic type are statistically<br />

significant at p < .05.<br />

I tested for the proportionality of effects us<strong>in</strong>g a simple <strong>in</strong>teraction between marital<br />

duration and each of the predictor variables. The results of these tests for proportionality<br />

are shown <strong>in</strong> Table 4. I used Model A <strong>in</strong> Table 2 as the basel<strong>in</strong>e and consider whether the<br />

addition of nonproportional effects yields a better-fitt<strong>in</strong>g model. Aga<strong>in</strong>, each model allow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

nonproportionality was compared with the basel<strong>in</strong>e model via differences <strong>in</strong> the<br />

LR and BIC statistics. I cont<strong>in</strong>ued to attach greater weight to the values of BIC to test<br />

whether the null hypothesis of proportionality should be rejected.<br />

Us<strong>in</strong>g BIC as the criterion, I found that none of the models allow<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

nonproportionality yield a better fit to the data than the basel<strong>in</strong>e model. The LR statistic<br />

suggests nonproportionality for hav<strong>in</strong>g a premarital birth, the wife be<strong>in</strong>g older, the wife’s<br />

education, the husband’s education, hav<strong>in</strong>g a wife with divorced parents, and be<strong>in</strong>g black.<br />

With the exception of be<strong>in</strong>g black, these are not the same variables for which the LR<br />

statistics suggested an <strong>in</strong>teraction with historical time. Thus, it is not likely that<br />

nonproportionality produced these potential <strong>in</strong>teractions with historical time.<br />

With respect to be<strong>in</strong>g black, the nonproportional effect <strong>in</strong>dicates an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly positive<br />

difference across marital duration (result not shown). This pattern strongly suggests<br />

that nonproportionality is not implicated <strong>in</strong> the decreas<strong>in</strong>g effect of be<strong>in</strong>g black across<br />

time shown <strong>in</strong> Table 3. If nonproportionality was <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g the chang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

effect of be<strong>in</strong>g black across historical time, it would have <strong>in</strong>volved an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly negative<br />

difference across marital duration.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, I tested for an <strong>in</strong>teraction between year of marriage and marital duration. If<br />

period effects are present, then the effects of year of marriage should be nonproportional.

344 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

Given the rise <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce over time, I anticipated that the nature of the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

should be a decreas<strong>in</strong>g effect of year of marriage at longer marital durations (because<br />

successive marriage cohorts experience a particular marital duration dur<strong>in</strong>g later periods<br />

when the risk of divorce is greater). The result<strong>in</strong>g model (not shown) does fit the data<br />

better than the basel<strong>in</strong>e model (Model χ 2 = 2,976.54, BIC = –2,770.98). The coefficient<br />

for the <strong>in</strong>teraction between year of marriage and marital duration is statistically significant<br />

(us<strong>in</strong>g the BIC criterion for strong evidence) and negative (e β = .999). This <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

is consistent with the notion that there is a period <strong>in</strong>fluence on the risk of marital<br />

dissolution. Inclusion of this <strong>in</strong>teraction term does not alter the coefficients (or standard<br />

errors) associated with any of the other covariates. Nor does <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g this <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

term alter any of the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs shown <strong>in</strong> Tables 2 and 3.<br />

How Robust Are the F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs?<br />

I conducted several sensitivity tests to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether the results are robust to different<br />

model specifications and restrictions on the data. First, I considered whether different<br />

results would be obta<strong>in</strong>ed if I coded age at marriage and year of marriage as a series of<br />

dummy variables <strong>in</strong>stead of us<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>uous variables. Because of the number of potential<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractions, I estimated a separate model for each <strong>in</strong>teraction between a particular<br />

age at marriage and year of marriage (us<strong>in</strong>g the age at marriage and year of marriage<br />

categories represented <strong>in</strong> Table 1). These models do not reveal a pattern of <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

between age at marriage and year of marriage that is otherwise masked by us<strong>in</strong>g cont<strong>in</strong>uous<br />

variables (see Appendix).<br />

Second, I considered the possibility that the results may be biased somehow by the<br />

fact that women who marry <strong>in</strong> earlier historical periods are more heavily weighted toward<br />

earlier ages at marriage. To address this issue, I reconfigured the sample and reestimated<br />

the models us<strong>in</strong>g data on marriages formed after 1959. I also formed a sample based on<br />

all years of marriage but restricted marriages to those formed before age 23, yield<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

sample <strong>in</strong> which the maximum age at marriage is consistent across year of marriage. For<br />

the sample restricted to women who marry before age 23, accord<strong>in</strong>g to values of the BIC<br />

statistic, the same <strong>in</strong>teraction as revealed <strong>in</strong> Table 2 yields a better model fit: the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

of be<strong>in</strong>g black with year of marriage (see Appendix). The coefficients from this model<br />

are similar to those estimated from the full sample.<br />

In the sample restricted to marriages formed after 1959, the <strong>in</strong>teraction between be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

black and marriage cohort yields weak evidence of a better-fitt<strong>in</strong>g model. The important<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t to note from models estimated on this sample, though, is that no new <strong>in</strong>teractions<br />

appeared when a different set of marriage ages was used. The lack of a substantial<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction between be<strong>in</strong>g black and year of marriage attests to the need for a long historical<br />

sequence to detect substantial changes <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce.<br />

Does Cohabitation Make a Difference?<br />

One substantial change <strong>in</strong> the nature of <strong>in</strong>timate relationships has been the sudden and<br />

steep rise <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cidence and prevalence of premarital cohabitation (Bumpass and Sweet<br />

1989). Much research has l<strong>in</strong>ked premarital cohabitation to an <strong>in</strong>creased risk of marital<br />

dissolution (Ax<strong>in</strong>n and Thornton 1992; Bumpass, Sweet, and Cherl<strong>in</strong> 1991; DeMaris and<br />

MacDonald 1993; Mann<strong>in</strong>g and Smock 1994; Thomson and Colella 1992). In this section,<br />

I seek to answer two questions. First, has the effect of premarital cohabitation on<br />

divorce changed over time? Second, are the relationships between the measured covariates<br />

and divorce somehow altered by the substantial <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> premarital cohabitation<br />

over the past several decades?<br />

I made use of <strong>in</strong>formation on premarital cohabitation conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> rounds 4 and 5 of<br />

the NSFG, exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g marriages formed after 1964. I replicated the models shown <strong>in</strong><br />

Table 2, first us<strong>in</strong>g premarital cohabitation as a predictor variable and then exclud<strong>in</strong>g

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 345<br />

this variable. The results <strong>in</strong>dicated no evidence that the effect of premarital cohabitation<br />

on the risk of divorce has changed over the relatively short period be<strong>in</strong>g considered (see<br />

Appendix). Nor does the <strong>in</strong>clusion of cohabitation <strong>in</strong> any of the models alter the conclusions<br />

reached about the lack of <strong>in</strong>teraction between the other covariates and historical<br />

period. Consistent with prior research, the estimated effect of premarital cohabitation<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicates an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the risk of divorce (by about 35%). Also <strong>in</strong> results not shown, I<br />

found the effects of premarital cohabitation to be proportional across marital duration.<br />

Variation <strong>in</strong> Effects by Race<br />

I conclude the analysis by estimat<strong>in</strong>g models separately for blacks and whites. Not only<br />

does the effect of race vary by year of marriage, but there is also prior evidence to suggest<br />

that the effects of various covariates on divorce may differ by race (Mart<strong>in</strong> and<br />

Bumpass 1989; Teachman 1986). Thus, by estimat<strong>in</strong>g models separately by race, I attempted<br />

to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether the effects of the measured covariates varied over time differently<br />

for blacks and whites (results not shown).<br />

I reestimated the basel<strong>in</strong>e model shown <strong>in</strong> Table 2 for blacks and whites only. I added<br />

to the basel<strong>in</strong>e model an <strong>in</strong>teraction between race and year married. The results <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

the strong <strong>in</strong>teraction between race and year married <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> Table 2. I then estimated<br />

the basel<strong>in</strong>e model separately for blacks and whites, thereby allow<strong>in</strong>g the effects of all the<br />

covariates to vary accord<strong>in</strong>g to race. These models were substantially less well fitt<strong>in</strong>g than<br />

a model that constra<strong>in</strong>s the effects of the covariates to be equal across race. Thus, a model<br />

that allows an <strong>in</strong>teraction between race and year married fits better than the basel<strong>in</strong>e model,<br />

and a model that allows <strong>in</strong>teractions between race and the rema<strong>in</strong>der of the covariates does<br />

not fit better. Although it is possible that a smaller subset of covariates may <strong>in</strong>teract with<br />

race, I did not search for such <strong>in</strong>teractions, given the purposes of this article and the lack of<br />

otherwise strong theoretical guidance to identify these <strong>in</strong>teractions.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

Us<strong>in</strong>g five rounds of the NSFG, I tested for changes <strong>in</strong> the effects of basic sociodemographic<br />

variables on the risk of divorce. In the ma<strong>in</strong>, most effects have rema<strong>in</strong>ed constant<br />

across a period dur<strong>in</strong>g which rates of divorce varied substantially. The results are robust<br />

to different model specifications and def<strong>in</strong>itions of the sample. Nor can the results be<br />

attributed to the nonproportionality of effects across different marital durations.<br />

Only one clear-cut <strong>in</strong>teraction with historical time was found: that <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the effect<br />

of race. Specifically, there was a convergence over time <strong>in</strong> the risk of marital dissolution<br />

between whites and blacks because the risk of marital dissolution rose more rapidly<br />

for whites than for blacks. I offer the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the <strong>in</strong>teraction between<br />

race and historical time. Specifically, the decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g economic position of many blacks and<br />

their less favorable marriage-market conditions, when comb<strong>in</strong>ed with the growth of alternatives<br />

to marriage and greater acceptance and prevalence of out-of-wedlock childbear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and cohabitation, means that blacks who marry are an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly select subgroup of<br />

all blacks. Blacks marry at later ages and are less likely to ever marry than are whites<br />

(Cherl<strong>in</strong> 1992; Teachman et al. 2000). Indeed, the environments faced by blacks and<br />

whites have diverged sufficiently that the current situation is a reversal of historical patterns.<br />

Before 1950, blacks married earlier than whites and were more likely to have ever<br />

married (Sweet and Bumpass 1987). S<strong>in</strong>ce 1950, blacks have delayed marriage more than<br />

whites, yield<strong>in</strong>g higher proportions who never marry.<br />

The result of these changes is that blacks who marry are likely to be selective of<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals who are committed to marriage and therefore are less likely to divorce. As a<br />

consequence, although both blacks and whites have been subject to the pervasive upward<br />

surge <strong>in</strong> divorce over the past several decades, the <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g selectivity of blacks <strong>in</strong>to<br />

marriage has yielded a somewhat slower <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the risk of marital dissolution.

346 Demography, Volume 39-Number 2, May 2002<br />

The chang<strong>in</strong>g effect of be<strong>in</strong>g black aside, the limited evidence for change <strong>in</strong> the effects<br />

of a range of basic sociodemographic predictors of divorce constitutes impressive<br />

evidence for the pervasive impact of historical period on the risk of marital dissolution.<br />

For a wide range of variables, there is little evidence of deviation from recent historical<br />

shifts <strong>in</strong> divorce. These results mirror the sentiment of Thornton and Rodgers (1987:20)<br />

that “the degree of uniformity of the historical period effects across population subgroups<br />

has been remarkable.”<br />

Although it is important to know that the effects of historical period have been pervasive,<br />

it still begs the next logical question: what is it about historical periods that<br />

affects the risk of divorce? This question is all the more important, given the recent<br />

level<strong>in</strong>g of divorce rates <strong>in</strong> the United States (Goldste<strong>in</strong> 1999), a level<strong>in</strong>g that cannot be<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>ed by compositional factors or the rise <strong>in</strong> nonmarital cohabitation. There is grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

evidence, therefore, that marriages are subject to the <strong>in</strong>fluence of powerful<br />

aggregate-level forces that are not yet well understood. Subsequent research should focus<br />

on identify<strong>in</strong>g and quantify<strong>in</strong>g the characteristics of historical periods that have led<br />

to such pervasive effects.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, as a note of caution, I rem<strong>in</strong>d readers that there may be other variables not<br />

considered <strong>in</strong> the current study that may have effects that vary across time. In particular,<br />

it would be beneficial for subsequent research to consider the impact of a wider range of<br />

variables that may be more tightly l<strong>in</strong>ked to the <strong>in</strong>strumental and expressive exchange<br />

that occurs between spouses. For example, more <strong>in</strong>formation about changes <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

of variables, such as wives’ labor force participation, occupations, and gender-role<br />

ideology and the division of household labor, could provide additional evidence about<br />

the nature of period effects on marital dissolution. On the basis of the exchange model,<br />

South (2001) outl<strong>in</strong>ed good reasons for expect<strong>in</strong>g the effect of wives’ labor force participation<br />

on divorce to change across time, and his empirical results suggest an effect that<br />

has become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly positive. South’s f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>dicate the complexity of factors<br />

that <strong>in</strong>fluence divorce and argue for care <strong>in</strong> specify<strong>in</strong>g the components of marriage that<br />

may be important to marital stability <strong>in</strong> a particular context. Although there is evidence<br />

that a wide range of important risk factors have consistent effects on divorce over time,<br />

the chang<strong>in</strong>g nature and context of marital unions argues for the cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong>vestigation<br />

of a wider range of factors that can be l<strong>in</strong>ked to marital cohesion.

<strong>Stability</strong> <strong>Across</strong> <strong>Cohorts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Divorce</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> <strong>Factors</strong> 347<br />

Appendix Table A1. Estimates of Model Fit for Various Sensitivity Models<br />

____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________<br />

Marriages Formed After 1959 Marriages Formed Before Age 23<br />

Model χ2 / df BIC Model χ2 / df BIC<br />

Model Model χ2 df Difference BIC Difference Model χ2 df Difference BIC Difference<br />

A: Basel<strong>in</strong>e Additive Model 2,056.08 22 –1,864.82 –– 2,476.85 22 –2,283.53<br />

B: A + Age at Marriage × Year<br />

Married 2,057.55 23 1.47/1 –1,856.76 8.06 2,480.60 23 3.75/1 –2,278.48 5.05<br />

C: A + Husband’s Age at Marriage<br />