THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA V.V. Krishna - Unesco

THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA V.V. Krishna - Unesco

THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA V.V. Krishna - Unesco

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>REPUBLIC</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>INDONESIA</strong><br />

Introduction<br />

V.V. <strong>Krishna</strong><br />

Indonesia proclaimed its independence on August 17, 1945, after more than 350 years under<br />

Dutch occupation. During this long colonial period, Indonesians frequently fought to restore<br />

their pre-colonial independence. Finally, in the early 20th century, attempts to overthrow the<br />

Dutch by force were replaced by the development of nationalist organizations that sought<br />

change and reforms through political means. The Japanese invasion in 1942 and occupation<br />

until 1945 further strengthened the determination of the nationalist movement.<br />

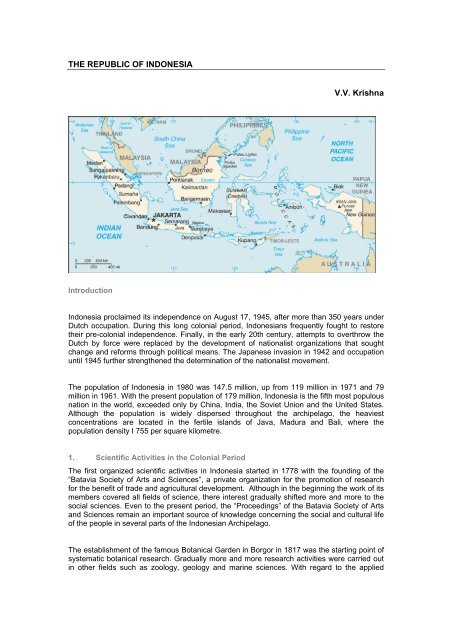

The population of Indonesia in 1980 was 147.5 million, up from 119 million in 1971 and 79<br />

million in 1961. With the present population of 179 million, Indonesia is the fifth most populous<br />

nation in the world, exceeded only by China, India, the Soviet Union and the United States.<br />

Although the population is widely dispersed throughout the archipelago, the heaviest<br />

concentrations are located in the fertile islands of Java, Madura and Bali, where the<br />

population density I 755 per square kilometre.<br />

1. Scientific Activities in the Colonial Period<br />

The first organized scientific activities in Indonesia started in 1778 with the founding of the<br />

“Batavia Society of Arts and Sciences”, a private organization for the promotion of research<br />

for the benefit of trade and agricultural development. Although in the beginning the work of its<br />

members covered all fields of science, there interest gradually shifted more and more to the<br />

social sciences. Even to the present period, the “Proceedings” of the Batavia Society of Arts<br />

and Sciences remain an important source of knowledge concerning the social and cultural life<br />

of the people in several parts of the Indonesian Archipelago.<br />

The establishment of the famous Botanical Garden in Borgor in 1817 was the starting point of<br />

systematic botanical research. Gradually more and more research activities were carried out<br />

in other fields such as zoology, geology and marine sciences. With regard to the applied

sciences, much attention was given to agricultural research especially on export crops, and<br />

later to medical research; important contributions were made in both fields.<br />

The Universities did not have a major part in the last two decades of Dutch Colonial rule. This<br />

was understandable as the first school of higher learning was founded abroad for a university<br />

degree and so only, a small minority could pursue scientific research. Most of the research<br />

was done by the Dutch scientists and other foreign scientists employed by the Dutch. This<br />

isolatation of local researchers had consequences after independence.<br />

The other development during the colonial period was the establishment of an organization<br />

for the promotion and coordination of scientific research in 1928 by Government Decree the<br />

“Natuurwetenschappelijke Raad Voor Nederlandsch Indie” (The Natural Science Council for<br />

the Netherlands Indies). The main objective of this organization was to stimulate and<br />

coordinate research, to function as a point of contact between scientists in the country and<br />

abroad and to act as an advisory body to the Government on matters relating to the natural<br />

sciences.<br />

Twenty years later, in 1948, another organization was created, the “Organization for Scientific<br />

Research” which was intended to become a national research council. Its primary aim was to<br />

stimulate, support and coordinate research that was important for the country. A similar<br />

organization was established for the Natural Sciences, the “Institute of Natural Sciences”. It<br />

was this latter organization, which organized the Fourth Pacific Science Congress, held in<br />

Indonesia in 1929. After the transfer of sovereignty, which took place in the last days of<br />

December 1949, Indonesia encountered a number of problems in many fields, including<br />

scientific research. Since most scientific research was done by the Dutch, after the transfer of<br />

sovereignty, many of these scientists left the country.<br />

1.1 Developments in S&T Policy Institutions after Independence, 1949<br />

As soon as the country proclaimed independence in 1945, a document on the ‘Constitution<br />

1945 of Republic of Indonesia’ was issued. In this document chapter 31 assigned an<br />

important role for S&T in the development of the country. From 1950, Indonesia started its<br />

programme of expanding education at all levels and science and technology. In 1956, the<br />

government formed the Indonesian Council of Sciences to coordinate developments in S&T<br />

and to advise the government on science and technology policy.<br />

The new regime of President Suharto, established in 1966, begun to promote science and<br />

technology for development through a planning process of Five Year Development Plans.The<br />

first Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology (IMRT) was created in 1970. Following<br />

this, the government established the National Research Centre for Science and Technology<br />

(called PUSPIPTEK) and the Life Sciences Centre. The PUSPIPTEK even today remains the<br />

country’s main R&D research complex. In 1984, the President Suharto formed the National<br />

Research Council (NRC) by constituting members from academia, R&D institutions and<br />

industry to advise the government on S&T; and to work in close collaboration with the Ministry<br />

of Research and Technology.<br />

Besides the developments noted above, Indonesia embarked on a planned process of<br />

development and S&T was given importance in this process. The First Five Year<br />

Development Plan (PELITA I) 1969 – 1974, carried out with the help of foreign governments<br />

and international organizations in the forms of loans grants and expertise, was aimed at<br />

getting the economy of the country out of its precarious position.

PELITA II (1974-75 to 1978-79), set out development objectives and provided directions for<br />

the desired growth process and for the order of priorities. The Second Plan focused on<br />

employment opportunities, a rising level of income, a more equitable distribution of<br />

development projects among the various regions of the country, greater economic and social<br />

integration of the region into one effective national entity and an enhanced quality of life<br />

including its environmental, cultural and nutritional aspects. With regard to the policy on<br />

research and development, focus was placed in the short term on R & D in agriculture,<br />

industry and mining. Cross-sectoral research activities in population, health education, social<br />

attitudes, communication etc, were also emphasized in this plan.<br />

Science and technology activities during PELITA III (1979-80 to 1983-84) were grouped into<br />

pure and applied sciences, supporting each other and directed towards the requirements of<br />

short-and long-term developments. The fifth Five Year Development Plan (PELITA V) laid<br />

down the task for the National Research Council to prepare the formulation of the principal<br />

National Programme in the fields of research and technology through planning and national<br />

development strategy. This exercise evolved a national Matrix on research and technology to<br />

be followed and further developed by other national level R&D and S&T institutions. Even<br />

though the planned process and having S&T component included in the national plans<br />

continues, some of the other developments in the recent times include:<br />

• National Development Programme of 2000, which became a Law in 2002 for National<br />

System of Research and Development, and Application of Science and Technology<br />

• Mechanism and Schemes to Regulate Technology Transfer<br />

• Strategy Policy of National Science and Technology Development 2001-2005<br />

by IMRT<br />

• Law of 2003 on National Education System<br />

• Schemes on Entrepreneurship Development and New Technology Insurance<br />

Programmes by IMRT in 2003<br />

Among the above-mentioned policies, the National Law No. 18, 2002, on National System<br />

Research, Development, and Application of Science and Technology assumes considerable<br />

importance. The government has set up the direction and research development priority as<br />

stated in the National Development Strategic Policy for Science and Technology. The present<br />

structure of Organisation of S&T is shown in Figure-1.

Figure 1: S&T Organisation in Indonesia - National Expenditure on Research<br />

In Indonesia, the predominant proportion of gross national expenditure on research<br />

and development and S&T activities is funded through government sources. Compared<br />

to other neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and others, Indonesia<br />

spends a relatively low proportion (about 0.2% in 2001) of its GDP budget on science.<br />

This proportion has come down drastically from 0.47% of GDP Indonesia spent on R&D in

1980. As the table 1 shows, S&T and R&D expenditure in Indonesia did not witness any<br />

significant increase between 1999 and 2002.<br />

Table 1: S&T and R&D expenditure of Indonesia (figures in million rupees)<br />

Sector 1999 2000 2001 2002<br />

S&T 1061 1634 1385 1239<br />

R&D 648 659 656 635<br />

Source: Various Websites on Indonesian S&T system<br />

Table 2: Sources of R&D Funds in Indonesia 2000<br />

Sources Billion Rupiah Percentage<br />

Government 659 68.6%<br />

Universities 54 5.6%<br />

Private 247 25.7%<br />

Total 960 100%<br />

Source: Various Websites on Indonesian S&T system<br />

Indonesian S&T and R&D funding relies quite substantially on the government source<br />

of funding. In 2000-02, 68.6% of national R&D was spent by the government, 25.7% by<br />

the private industry and 5.6% by the academic sector. Even from the limited sources of extra<br />

mural R&D funds, the type of allocation made in 1999 (See Table 3) reveals that directly<br />

relevant R&D components such as in universities, government laboratories etc<br />

have accounted for less than 12% and indirect NGO related R&D activities account for over<br />

92%.<br />

Table 3: Distribution of Extramural of Industry R&D Expenditure, 1999<br />

Recipient Rp. Billion %<br />

University 0.756 4.3<br />

Government R&D Inst 0.559 3.2<br />

Other company 0.046 0.3<br />

Overseas 0.894 5.1<br />

Others (NGOs, individuals, etc.) 15.248 87.1<br />

Total 17.503 100<br />

Source: IMRT and LIPI, 2003

As Table 4 shows, out of the R&D budget allocated to research institutions, four institutions<br />

including the one involved in Aerospace field, received substantial funding. It is clear from the<br />

above table that these four institutions are quite important for Indonesian S&T system.<br />

Table 4: Research Institution’s R&D Budget, 2003<br />

Non Departmental Research Institutions Rp. Billion<br />

Indonesian Institute of Science (LIPI) 137.6<br />

National Institute for Atomic Energy (BATAN) 78.5<br />

Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology (BPPT) 60.9<br />

National Institute for Aerospace and Aeronautic (LAPAN) 51<br />

National Coordinating Board for Survey and Mapping (BAKOSURTANAL) 4.0<br />

National Institute for Standardization (BSN) 0.2<br />

Source: MORT, 2005<br />

2. Universities and Human Resources<br />

Higher education in Indonesia began at the end of the Nineteenth Century with the<br />

establishment of medical education for local doctors in Jakarta. After independence in 1949,<br />

particularly after Education Act of 1961, the country witnessed a good deal of progress in<br />

higher education. In 1950, there were 10 institutions of higher education with 6500 students.<br />

In twenty years in 1970, there were 450 private and state funded institutions of higher learning<br />

with enrolments of 237,000 students. This increased further to 900 institutions in 1990 with<br />

nearly 1.5 million students. In 2004-05, there are some 2600 institutions of higher education<br />

including 82 public institutions. However, given different types of higher educational<br />

institutions, one good source indicates that there are currently 51 state/public universities<br />

(including several teacher-training institutions), 26 state/public polytechnics (engineering,<br />

commerce and agriculture) and 1,328 private higher education institutions (including<br />

academies, polytechnics and teacher training institutions). Besides, there are also Islamic<br />

higher education institutions (both private and state/public) which are under<br />

the control of the Ministry of Religious Affairs<br />

(http://www.rihed.seameo.org/hesystem/indonesiaHEsystem.htm). The Table-7 below shows<br />

some important public and private universities in Indonesia. According to the estimates given<br />

by Djanali (2005), the period of 1990 and 1996 saw enrolments in public universities doubling<br />

to around 1.5 million and enrolments in private universities rose by one third to about 1.9<br />

million. An average of 14,540 additional teachers were recruited for higher education every<br />

five years between 1968 and 1993.<br />

Table 5 shows that both in terms of education inputs (public expenditure on education), and<br />

participation in education, Indonesia in general lacks behind its South East Asian neighbours.<br />

Indonesia lags far behind its South East Asian neighbours and the Republic of Korea<br />

concerning public expenditure and the gross enrolment ratio in secondary and particularly in<br />

tertiary education. Only as regards the adult literacy rate for both adult males and females is<br />

Indonesia on a par with the other East Asian countries, because of the vast expansion in<br />

primary education during the Soeharto era. In 1995/96, just before the Asian economic crisis,<br />

central government expenditure on education accounted for 15 percent of total central<br />

government expenditure or Rp. 12 trillion in absolute terms. However, in 2004 public<br />

expenditure on education accounted for only 10 percent of central government expenditure or<br />

Rp. 25 trillion in absolute terms. Aside from the fact, that Indonesia’s public expenditure on

human resource development is even lower than the average low-income country, let alone<br />

the average middle-income country, the current education and training system in general<br />

does not meet the needs of industry. The reason is that the general secondary education<br />

system relies on rote learning, and does not develop adequate mastery of basic literacy, basic<br />

numeracy, and thinking and creative skills. (Thee Kian Wie, ‘The Technology and Indonesia’s<br />

industrial competitiveness’, Asian Development Bank, Mimeo). According to the recent<br />

UNESCO 2005, report gross enrolment ratio witnessed considerable improvement from 9.2 in<br />

1990 to 15 in 2000 as shown in Table 6 below.<br />

Table 5: Gross enrolment ratio, 2000/02<br />

Country<br />

Public expenditure<br />

on education (% of<br />

total government<br />

expenditure, 2003)<br />

Primary (% of<br />

relevant age group)<br />

Secondary (% of<br />

relevant age group)<br />

Tertiary (% of<br />

relevant age group)<br />

Male (% ages 15 and<br />

older)<br />

Indonesia 9.8 111 58 15 92 83<br />

Malaysia 20.0 95 70 27 92 85<br />

Philippines 14.0 112 82 31 93 93<br />

Thailand 28.3 98 83 37 95 91<br />

China - 116 67 13 95 87<br />

The Republic of Korea 13.1 104 90 85<br />

Table 6: Gross Enrolment Ratios 1970-2000<br />

1970 1980 1990 2000<br />

Secondary Education 16.1 29.0 44.0 57.0<br />

Higher Education 2.5 3.8 9.2 15.0<br />

Source: UNESCO (2005)<br />

Female (% ages 15<br />

and older)

Table 7: Main Universities in Indonesia<br />

Public Universities Private Universities<br />

Cenderawasih University, Jayapura<br />

University of Airlangga, Surabaya<br />

Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung<br />

Bogor Agricultural University<br />

Diponegoro University, Semarang<br />

Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta<br />

University of Indonesia, Jakarta<br />

Padjadjaran University<br />

Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan<br />

Sepuluh November Institute of Technology,<br />

Surabaya<br />

Sriwijaya University<br />

Universitas Islam Negeri<br />

Yogyakarta State University<br />

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_universities_in_Indonesia<br />

Brawijaya University<br />

Institut Seni Indonesia, Yogyakarta Sekolah Tinggi<br />

Seni Indonesia Surakarta, Surakarta<br />

Universitas Mataram, Mataram, West Nusa<br />

Tenggara Universitas Udayana, Denpasar, Bali<br />

Atma Jaya University<br />

Bina Nusantara University<br />

Parahyangan Catholic University<br />

STT Telkom, Bandung<br />

Tarumanagara University<br />

Trisakti University<br />

Pelita Harapan University<br />

Islam Indonesia University<br />

Petra Christian University, Surabaya<br />

Kristen Satya Wacana University, Salatiga<br />

3. Indonesia’s Main Science Institutions<br />

As noted earlier, Indonesia remains behind many Asian countries in several important<br />

aspects. One important indicator, which shows low importance and national effort in R&D and<br />

S&T, is the low level of spending for R&D, which was less than 0.2 percent of GDP during<br />

2000-02. This level of funding for R&D is much lower than several South Asian and South<br />

East countries. Public spending on education was also low by Asian standards, despite the<br />

rapid expansion of the educational system.<br />

The State Ministry for Research and Technology has the responsibility for coordinating R&D<br />

policy in Indonesia but has little control over the allocation of research expenditure. The<br />

Ministry operates a number of competitive grants and other programs for funding research,<br />

especially for universities. Budgets for government research institutions are allocated either<br />

through Ministries or directly through non-department agencies. The most important nondepartment<br />

research institutions include the Agency for Assessment and Application of<br />

Technology (BPPT) for industrial technology, the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) for<br />

basic sciences, the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), the National Nuclear Energy Agency<br />

(BADAN), and the National Institute for Aeronautics and Space (LAPAN). Nevertheless,<br />

agriculture remains the highest priority for government-supported research. IAARD in the<br />

Ministry of Agriculture is the largest government research agency in Indonesia with over 3,000<br />

researchers (Table 8). Together with IPARD (estate crops), FORDA (forestry) and the Centre<br />

for Fisheries R&D, agriculture receives by far the largest allocation of research staff by<br />

government research institutions. Table 8 lists Indonesia’s main science agencies, their fields<br />

of activity and research staff in the respective institutions. As can be seen agriculture and<br />

related research constitutes the predominant segment of the national S&T effort. As can be<br />

seen from the table below, Indonesia maintains two frontier based R&D institutions, namely<br />

Aerospace and Nuclear related research that both constitute 1800 full time researchers.

Table 8: Major government research institutions in Indonesia 1995-2000<br />

Name of Research Institution Fields of activity Research staff*<br />

Indonesia Agency for Agricultural Research and<br />

Development (IAARD)<br />

Agricultural crops and<br />

livestock<br />

3063<br />

Central Statistics Agency (BPS) Statistics 1343<br />

Agency for Assessment and Application of Technology<br />

(BPPT)<br />

Industrial Technologies 2074<br />

Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Basic sciences 1692<br />

National Nuclear Energy Agency (BADAN) Nuclear Energy 1314<br />

National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (LAPAN) Aeronautics and space 487<br />

Forestry Research and Development Agency<br />

(FORDA)<br />

Indonesian Planters Association for Research and<br />

Development (IPARD)<br />

Centre for Oil and Gas Technology Research and<br />

Development<br />

Agency for Trade and Industry Research and<br />

Development<br />

Centre for Fisheries Research and Development 308<br />

National Coordination Agency for Survey and Mapping<br />

(BAKOSURTANAL)<br />

*Research staff includes those with University degree (B.Sc., M.Sc., or Ph.D.). Data are from 1995-2000.Sources:<br />

RISTEK (1996, 2002); IAARD (Statistik Penelitian Pertanian: Sumberdaya, Program dan Hasil Penelitian, 2000).<br />

4. Indonesia’s Agriculture Research<br />

In Indonesia, the central government is the primary source of funds for agricultural research.<br />

The international agencies and donor institutions played a major part in developing<br />

agricultural research in Indonesia, especially during the 1980s and early 1990s. This was the<br />

period when Indonesia’s capacity in agricultural research was established. IAARD is the<br />

primary body responsible for conducting and coordinating crop and livestock research in the<br />

country. Research institutes for estate commodities are managed by the Indonesian Planters<br />

Association for Research and Development (IPARD). IPARD, though largely autonomous and<br />

self-financed, is nominally under the guidance of IAARD. Forestry and fisheries research were<br />

separated from IAARD when the Ministry of Forestry and Ministry of Marine Affairs and<br />

Fisheries were created. The principal role of universities in agricultural research has been to<br />

train the scientific and technical personnel employed in government research institutes and<br />

the private sector.<br />

International agricultural research centres play an important role in Indonesia’s agricultural<br />

research system. There are a number of international research agencies conducting research<br />

in Indonesia. These are the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and the SE<br />

Asia regional offices of the International Centre for Research on Agro-Forestry (ICRAF) and<br />

the International Potato Centre (CIP). The UN ESCAP CGPRT Centre, which conducts<br />

486<br />

429<br />

343<br />

328<br />

239

socioeconomic research on secondary food crops, and the ASEAN-funded South East Asia<br />

Regional Centre for Tropical Biology (BIOTROP) are also located in Indonesia. IAARD has<br />

cooperative research arrangements with several other international agricultural research<br />

centres as well (including AVRDC, CIMMYT, ILRI, and IRRI) and agricultural research<br />

institutes in Japan, Europe, North America, and Australia. IAARD established a semiautonomous<br />

foundation in 1999, the Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer<br />

Management Office (IPTTMO), to help commercialize IAARD innovations. This office has<br />

responsibility for patenting and licensing IAARD innovations to private firms.<br />

5. Industry and High Technology<br />

Although Indonesia's rapid industrial growth and transformation during the past three decades<br />

was undoubtedly accompanied by technological upgrading, particularly since the mid-1980s,<br />

the development of Indonesia's industrial technological capabilities (ITCs) has lagged behind<br />

that of other Asian neighbours, particularly the Republic of Korea and China. These low ITCs<br />

are, amongst others, reflected by the low percentage of high technology exports of<br />

Indonesia’s manufactured exports, as compared to those of the other East Asian countries<br />

(Table 9)<br />

Table 9: The amount and percentage of high technology exports of selected East<br />

Asian countries, 2003<br />

Country High-technology exports (millions<br />

of US$)<br />

Indonesia 4580 14<br />

Malaysia 47042 58<br />

Singapore 71421 59<br />

Thailand 18202 30<br />

China 107543 27<br />

Percentage of manufactured exports<br />

Source: World Bank: World Development Indicators, 2005, table 5.12, pp. 314-8.<br />

Note: High technology exports are products with high R & D intensity, as in aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals,<br />

and scientific instruments.<br />

5.1 Aircraft Industry<br />

Under the leadership of the then minister of state for research and technology,<br />

Bacharuddin J. Habibie, the government attempted to move into aeronautics with foreign<br />

technological assistance in the 1970s. The Archipelago Aircraft Industry (IPTN) was<br />

established in 1976 to assemble aircraft under license from Construcción Aeronauticas of<br />

Spain, and helicopters under license from Aerospatiale of France and Messerschmitt of<br />

Germany. In 1979, IPTN designed and produced a 35 passenger aircraft (CN-235) with the<br />

Spanish partner. This plane was produced from 1986 when IPTN had delivered 194 aircraft,<br />

almost entirely to domestic buyers. In 1994, IPTN rolled out its first independently designed<br />

aircraft, a 50 passenger commuter aircraft (N250) (Soedarsono et al 1998). IPTN is valued at<br />

US$3 billion in 1998 and among its 15,000 employees about 2,000 were university graduates.<br />

(http://countrystudies.us/indonesia/71.htm & U.S. Library of Congress)

5.2 Biotechnology in Indonesia<br />

Modern biotechnology in Indonesia was institutionalised in October 1994 with the<br />

establishment of the Biotechnology Consortium (IBC). The aim of IBC is to actively engage in<br />

mastering, developing and making use of the benefits of biotechnology for the people, country<br />

and environment conservation. These activities are conducted by building up:<br />

• promoting cooperation among government and private institutions working in the field<br />

of biotechnology,<br />

• communication and synergistic cooperation with foreign institutions in the field of<br />

biotechnology which are related, and<br />

• assisting government in developing of sectors that relate to biotechnology.<br />

At present, more than 34 institutions belong to the government and private sector working in<br />

the field of biotechnology. (www.binasia.net/binasiadownload/downloadFile.asp?).In 2005, the<br />

country hosted the BINASIA-Indonesia National Workshop to promote active participation of<br />

biotechnology-stakeholders in the Network and international cooperation among participating<br />

countries. One of the objectives of this workshop was to deliberate the status of<br />

biotechnological developments and the national priority areas of Indonesia. However,<br />

although the country is working in the area of biotechnology but a government policy on this is<br />

yet to be issued.<br />

Table 10: S&T Publications from the Web of Science (SCI)<br />

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005<br />

Bangladesh 324 359 346 389 423 471 430 501<br />

PR China 18833 23398 29004 33206 38469 46900 47306 56,524<br />

India 16037 17104 15983 17501 18525 20803 20830 21,164<br />

Indonesia 342 381 422 486 395 489 455 560<br />

Japan 68585 70435 69773 70215 71207 78046 69433 66,411<br />

Korea 10458 11894 13200 15519 16642 20529 21939 23,004<br />

Malaysia 798 869 814 922 934 1171 1254 1,586<br />

Mongolia 34 38 45 39 41 105 97 54<br />

Pakistan 601 577 596 531 691 763 903 1,060<br />

Philippines 311 344 351 315 410 440 424 486<br />

Singapore 2490 3046 3392 3802 4238 4846 5109 5,419<br />

Sri Lanka 124 168 167 157 176 264 226 290<br />

Taiwan 8745 9152 9346 10780 11011 12675 13146 14,057<br />

Thailand 935 1043 1185 1331 1591 2048 2047 2,543<br />

Vietnam 239 249 322 356 346 497 412 573<br />

Total 128856 139057 144946 155549 165099 190047 184011 196,237

6. Concluding Remarks<br />

Indonesia witnessed a number of crises during the last decade. First the Asian financial crises<br />

of 1990s and then the Tsunami and a number of other natural disasters affected the economy<br />

in a number of ways. To some extent, these compounding problems diverted the attention of<br />

government away from the growing needs and demands of the R&D system.<br />

The current investment of around 0.2% of GDP on R&D is very inadequate to meet the<br />

objectives and challenges outlined in the government’s S&T policy, particularly those<br />

concerning the new technologies. In a relative sense, much of Indonesian strength in<br />

innovation is in the agriculture and related areas of research. In a situation of low levels of<br />

R&D investment and efforts during the last three decades, over emphasis on developing high<br />

technology and high capital-intensive sectors such as nuclear and aviation industries has<br />

further compounded the S&T and R&D problems for Indonesia. This resulted in the spreading<br />

of thin financial resources to a number of R&D projects without having to witness any<br />

reasonable degree of success and output. As can be seen from Table 10, compared to other<br />

South East Asian neighbours, Indonesian R&D output as measured in research papers is<br />

quite low for the period 1998 and 2005. Indonesian output is comparable to countries such as<br />

Bangladesh, Vietnam and Sri Lanka. Secondly, one sector which has showed some<br />

promising results, has been the manufacturing sector. Given the growing challenges of new<br />

technologies and the importance of ICT and BT, the government needs to increase the<br />

R&D/GDP ratio to at least three times to 0.6% in the coming three to five years. Government<br />

need to evolve institutional innovations in S&T policies to mobilize private sector industry to<br />

invest greater sums in R&D.<br />

7. References<br />

Soedarsono, A.A. L.M.Susan and Yildirim Omurtag, (1998), ‘Productivity Improvement at a<br />

High-Tech State-Owned Industry – An Indonesian Case Study of Employee<br />

Motivation’, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 45(4).<br />

Aiman, S. Lukman Hakim and Manaek Simamora (2005), ‘National Innovation System of<br />

Indonesia: A Journey and Challenges’ Paper presented at the Seminar at AEGIS,<br />

UWS, Sydney, 2005.