McKee et al 2007.pdf - Yale School of Medicine - Yale University

McKee et al 2007.pdf - Yale School of Medicine - Yale University

McKee et al 2007.pdf - Yale School of Medicine - Yale University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION<br />

Smoking Status as a Clinic<strong>al</strong> Indicator<br />

for Alcohol Misuse in US Adults<br />

Sherry A. <strong>McKee</strong>, PhD; Tracy F<strong>al</strong>ba, PhD; Stephanie S. O’M<strong>al</strong>ley, PhD;<br />

Jody Sindelar, PhD; Patrick G. O’Connor, MD, MPH<br />

Background: Screening for <strong>al</strong>cohol use in primary care<br />

s<strong>et</strong>tings is recommended by clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines but<br />

is not adhered to as strongly as screening for smoking.<br />

It has been proposed that smoking status could be used<br />

to enhance the identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse in primary<br />

care and other medic<strong>al</strong> s<strong>et</strong>tings, but nation<strong>al</strong> data<br />

are lacking. Our objective was to investigate smoking status<br />

as a clinic<strong>al</strong> indicator for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse in a nation<strong>al</strong><br />

sample <strong>of</strong> US adults, following clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines<br />

for the assessment <strong>of</strong> these behaviors.<br />

M<strong>et</strong>hods: An<strong>al</strong>yses are based on a sample <strong>of</strong> 42 374 US<br />

adults from the Nation<strong>al</strong> Epidemiologic<strong>al</strong> Survey on Alcohol<br />

and Related Conditions (Wave I, 2001-2002). Odds<br />

ratios (ORs), 95% confidence interv<strong>al</strong>s (CIs), and test characteristics<br />

(sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative<br />

predictive v<strong>al</strong>ues, and positive likelihood ratio <strong>of</strong> smoking<br />

behavior [daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, or former]) were d<strong>et</strong>ermined<br />

for the d<strong>et</strong>ection <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking behavior<br />

and <strong>al</strong>cohol-related diagnoses, assessed by the Alcohol<br />

Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV.<br />

Author Affiliations:<br />

Departments <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry<br />

(Drs <strong>McKee</strong> and O’M<strong>al</strong>ley),<br />

Epidemiology and Public<br />

He<strong>al</strong>th (Drs F<strong>al</strong>ba and<br />

Sindelar), and Intern<strong>al</strong><br />

<strong>Medicine</strong> (Dr O’Connor), Y<strong>al</strong>e<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>,<br />

New Haven, Conn. Dr F<strong>al</strong>ba is<br />

now with the Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Economics, Duke <strong>University</strong>,<br />

Durham, NC.<br />

THE CURRENT NATIONAL INstitute<br />

on Alcoholism and<br />

Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA)<br />

Clinician’s Guide, Helping<br />

Patients Who Drink Too<br />

Much, 1 not only recommends screening for<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol use disorders but <strong>al</strong>so advocates<br />

screening for less severe “at risk” or hazardous<br />

drinking. The US Preventive Services<br />

Task Force (USPSTF) 2 recommends<br />

screening for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse (which<br />

includes hazardous drinking, <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

abuse, and <strong>al</strong>cohol dependence) and has<br />

assigned a grade-B recommendation for<br />

screening and brief interventions for hazardous<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol consumption in primary<br />

care s<strong>et</strong>tings. Even though screening 3-6 and<br />

brief interventions 7,8 provided in primary<br />

care s<strong>et</strong>tings are effective, clinicians have<br />

low rates <strong>of</strong> adherence to the guidelines<br />

for screening for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. 9,10 Using<br />

a nation<strong>al</strong> sample, Edlund <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong> 11 estimate<br />

that only 30% <strong>of</strong> individu<strong>al</strong>s who had a<br />

Results: Daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, and ex-smokers were more<br />

likely than never smokers to be hazardous drinkers (OR,<br />

3.23 [95% CI, 3.02-3.46]; OR, 5.33 [95% CI, 4.70-<br />

6.04]; OR, 1.19 [95% CI, 1.10-1.28], respectively). Daily<br />

and occasion<strong>al</strong> smokers were more likely to me<strong>et</strong> criteria<br />

for <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses (OR, 3.52 [95% CI, 3.19-3.90]<br />

and OR, 5.39 [95% CI, 4.60-6.31], respectively). For the<br />

d<strong>et</strong>ection <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking by current smoking (occasion<strong>al</strong><br />

smokersdaily smokers), sensitivity was 42.5%;<br />

specificity, 81.9%; positive predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue, 45.3% (vs<br />

population rate <strong>of</strong> 26.1%); and positive likelihood ratio,<br />

2.34. For the d<strong>et</strong>ection <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses by current<br />

smoking, sensitivity was 51.4%; specificity, 78.0%; positive<br />

predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue, 17.8% (vs population rate <strong>of</strong> 8.5%);<br />

and positive likelihood ratio, 2.33.<br />

Conclusions: Occasion<strong>al</strong> and daily smokers were at<br />

heightened risk for hazardous drinking and <strong>al</strong>cohol use<br />

diagnoses. Smoking status can be used as a clinic<strong>al</strong> indicator<br />

for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse and as a reminder for <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

screening in gener<strong>al</strong>.<br />

Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:716-721<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

716<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.<br />

primary care visit reported being screened<br />

for an <strong>al</strong>cohol or drug use problem. In contrast,<br />

physicians are much more likely to<br />

screen and apply brief interventions to<br />

address smoking behavior. 12,13 Studies <strong>of</strong><br />

physician and patient reports and medic<strong>al</strong><br />

record reviews find that the majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> primary care patients are screened for<br />

smoking status (81%). 14 Smoking status is<br />

more likely to be recorded in the medic<strong>al</strong><br />

chart than is drinking behavior. 15,16 Studies<br />

<strong>of</strong> medic<strong>al</strong> patients suggest that smoking<br />

status and <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse are highly<br />

associated, such that current smoking<br />

status may be used to help identify problem<br />

drinkers. 17-21 In a sample <strong>of</strong> German<br />

medic<strong>al</strong> patients, the rate <strong>of</strong> daily smoking<br />

was 47.1% in those with <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse,<br />

compared with 18.4% in the gener<strong>al</strong><br />

population. 20 In a sample <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>al</strong> and<br />

dent<strong>al</strong> patients, the rate <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking<br />

was 20.3% in current smokers and<br />

11.7% in current nonsmokers. 21

The Nation<strong>al</strong> Epidemiologic<strong>al</strong> Survey on Alcohol and<br />

Related Conditions (NESARC; Wave I, 2001-2002) 22 provides<br />

a unique opportunity to investigate the sensitivity<br />

and specificity <strong>of</strong> smoking status as an indicator <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

misuse among US adults following clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines<br />

for the assessment <strong>of</strong> these behaviors. Current and<br />

prior smoking behavior (daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, or former<br />

smoker) was assessed rather than nicotine dependence to<br />

be consistent with clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines for screening<br />

<strong>of</strong> smoking status in primary care s<strong>et</strong>tings. 23,24 Drinking<br />

behavior was assessed according to NIAAA screening guidelines,<br />

which recommend first assessing current drinking<br />

status and then hazardous drinking status, followed by <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

use diagnoses. Thus, the go<strong>al</strong>s <strong>of</strong> this study were to<br />

use the NESARC database to answer the following questions:<br />

(1) Can smoking status (daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, or former)<br />

be used to d<strong>et</strong>ect <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse (hazardous drinking and<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol-related diagnoses)? And (2) Is smoking status differenti<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

related to <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse?<br />

METHODS<br />

DATA SOURCES<br />

The NESARC study (Wave I, 2001-2002) was conducted by the<br />

NIAAA. The data were collected by person<strong>al</strong> interviews with<br />

43 093 civilian, noninstitution<strong>al</strong>ized adults (age, 18 years) residing<br />

in the United States. The response rate was reported to<br />

be 81% and was c<strong>al</strong>culated by multiplying the household response<br />

rate (89%), person response rate (93%), and sample frame<br />

response rate (99%). 22 African Americans, Hispanics, and adults<br />

aged 18 to 24 years were oversampled. In our an<strong>al</strong>yses, the data<br />

were weighted to account for oversampling and to adjust for<br />

nonresponse. The weighted data were further adjusted to be<br />

representative <strong>of</strong> the US civilian population using the 2000 decenni<strong>al</strong><br />

census. Further d<strong>et</strong>ails <strong>of</strong> the sampling, purpose, and<br />

weighting have been published elsewhere. 22<br />

DEFINITIONS OF SMOKING STATUS<br />

AND ALCOHOL MISUSE<br />

Current (anytime within the past 12 months) smoking and<br />

drinking behavior and <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnostic criteria were assessed<br />

with the Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities<br />

Interview Schedule–DSM-IV [Diagnostic and Statistic<strong>al</strong> Manu<strong>al</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Ment<strong>al</strong> Disorders, Fourth Edition] Version (AUDADIS-IV). 25<br />

The AUDADIS-IV has demonstrated both reliability and v<strong>al</strong>idity<br />

for the assessment <strong>of</strong> smoking and drinking behavior and<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol use disorders. 26-28<br />

Cigar<strong>et</strong>te Use<br />

In the present study, the NESARC data were coded into the following<br />

categories for past 12-month cigar<strong>et</strong>te use 29 :<br />

v Daily: someone who at the time <strong>of</strong> the survey was smoking<br />

cigar<strong>et</strong>tes at least once per day.<br />

v Occasion<strong>al</strong>: someone who currently smokes cigar<strong>et</strong>tes but<br />

not every day.<br />

v Ex-smoker: a nonuser who has previously been a daily or<br />

occasion<strong>al</strong> smoker.<br />

v Never smoker: a nonuser who has never used any tobacco<br />

product.<br />

Smoking status was assessed with the following variables:<br />

“tobacco use status” (current user, ex-user, or lif<strong>et</strong>ime non-<br />

user), “cigar<strong>et</strong>te smoking status” (smoked in the past 12 months<br />

or smoked prior to the last 12 months), and “usu<strong>al</strong> frequency<br />

when smoked.” As defined, these variables were designed to<br />

replicate the smoking status information that is typic<strong>al</strong>ly collected<br />

by he<strong>al</strong>th care providers in primary care and other medic<strong>al</strong><br />

s<strong>et</strong>tings and are recommended by clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines.<br />

23,24<br />

Hazardous Drinking<br />

The NIAAA guidelines, 1 which define hazardous drinkers as<br />

those exceeding sex-specific weekly limits (men, 14 drinks<br />

per week; women, 7 drinks per week) or exceeding daily drinking<br />

limits (men, 5 drinks per day; women, 4 drinks per day<br />

at least once in the past year) were used to define hazardous<br />

drinking. Current drinking in the NESARC was defined as<br />

“drank at least 1 <strong>al</strong>coholic drink in the last 12 months.” To d<strong>et</strong>ermine<br />

wh<strong>et</strong>her weekly quantity limits were exceeded, we converted<br />

the variable “average daily volume <strong>of</strong> <strong>et</strong>hanol intake” (see<br />

NESARC data notes for c<strong>al</strong>culation 30 ) to weekly number <strong>of</strong> drinks<br />

consumed (using a standard <strong>of</strong> 0.6 oz [17.0 g] <strong>of</strong> <strong>et</strong>hanol per<br />

drink). 31 To d<strong>et</strong>ermine wh<strong>et</strong>her daily criteria were exceeded,<br />

frequency <strong>of</strong> binge drinking was assessed with the variable <strong>of</strong><br />

“how <strong>of</strong>ten an individu<strong>al</strong> consumed 5 or more (for men) or 4<br />

or more drinks (for women) <strong>of</strong> any <strong>al</strong>cohol in the last 12<br />

months.” Frequencies <strong>of</strong> binge drinking were converted to days<br />

per week using the midpoints <strong>of</strong> the categoric<strong>al</strong> responses. These<br />

criteria for hazardous drinking are easily assessed in primary<br />

care s<strong>et</strong>tings.<br />

Alcohol Diagnoses<br />

The AUDADIS-IV uses DSM-IV 32 criteria to d<strong>et</strong>ermine <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

diagnoses. In he<strong>al</strong>th care s<strong>et</strong>tings, DSM-IV criteria are the standard<br />

by which <strong>al</strong>cohol abuse and dependence are diagnosed.<br />

A diagnosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol dependence requires 3 or more <strong>of</strong> the<br />

following events in the past year: tolerance; withdraw<strong>al</strong>; drinking<br />

more or longer than intended; persistent desire or unsuccessful<br />

efforts to cut down or control <strong>al</strong>cohol use; a great de<strong>al</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> time spent obtaining <strong>al</strong>cohol, using it, or recovering from<br />

its effect; important soci<strong>al</strong>, occupation<strong>al</strong>, or recreation<strong>al</strong> activities<br />

given up or reduced because <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol; and continued<br />

use despite knowledge <strong>of</strong> having a persistent or recurrent physic<strong>al</strong><br />

or psychologic<strong>al</strong> problem caused or exacerbated by <strong>al</strong>cohol.<br />

A diagnosis <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol abuse requires 1 or more <strong>of</strong> the following<br />

events in the past year: recurrent use resulting in failure<br />

to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home; recurrent<br />

use in physic<strong>al</strong>ly hazardous situations; recurrent <strong>al</strong>coholrelated<br />

leg<strong>al</strong> problems; and continued use despite having persistent<br />

or recurrent soci<strong>al</strong> or interperson<strong>al</strong> problems caused or<br />

exacerbated by <strong>al</strong>cohol. Individu<strong>al</strong>s who m<strong>et</strong> criteria for either<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol abuse or dependence were categorized as having an <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

diagnosis.<br />

STATISTICAL ANALYSES<br />

Absolute and relative frequencies <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse by smoking<br />

status were c<strong>al</strong>culated both with and without sample<br />

weights for each <strong>of</strong> the 3 outcomes (hazardous drinkers vs <strong>al</strong>l<br />

others, hazardous drinkers vs nonhazardous drinkers, and<br />

those with an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis vs <strong>al</strong>l others). Logistic regressions<br />

were used to an<strong>al</strong>yze the statistic<strong>al</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> differences<br />

in <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse rates by daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, and former<br />

smokers relative to never smokers. Using these regression results,<br />

we d<strong>et</strong>ermined an ordering <strong>of</strong> smoking status risk for<br />

the following ev<strong>al</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> smoking status as a clinic<strong>al</strong> indicator<br />

for each <strong>of</strong> the <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse outcomes. Occasion<strong>al</strong> smok-<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

717<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.

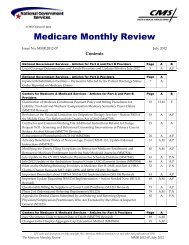

Table 1. Alcohol Misuse Outcomes by Smoking Status*<br />

Smoking<br />

Status<br />

All,<br />

No. (%)<br />

ers represented the highest risk level, followed by current smokers<br />

(occasion<strong>al</strong> daily), current or prior smokers<br />

(occasion<strong>al</strong>dailyformer), and last, <strong>al</strong>l subjects (occasion<strong>al</strong>dailyformernever).<br />

Specificity, sensitivity, positive<br />

predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue (PPV), negative predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue (NPV),<br />

and positive likelihood ratio (LR ) statistics were c<strong>al</strong>culated<br />

for successively lower levels <strong>of</strong> smoking risk. Sensitivity was<br />

c<strong>al</strong>culated as the proportion <strong>of</strong> individu<strong>al</strong>s with <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse<br />

who were at a particular smoking risk level (ie, rate <strong>of</strong> true<br />

positives). Specificity was c<strong>al</strong>culated as the proportion <strong>of</strong> individu<strong>al</strong>s<br />

without <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse, who were not at that particular<br />

smoking risk level (ie, rate <strong>of</strong> true negatives). Positive<br />

predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue was c<strong>al</strong>culated as the probability that the individu<strong>al</strong><br />

misused <strong>al</strong>cohol given that a particular level <strong>of</strong> smoking<br />

risk was m<strong>et</strong>. Conversely, NPV was c<strong>al</strong>culated as the probability<br />

that a person did not misuse <strong>al</strong>cohol given that the<br />

individu<strong>al</strong> was not at that level <strong>of</strong> smoking risk. The LR was<br />

c<strong>al</strong>culated as the ratio <strong>of</strong> the chance <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse in individu<strong>al</strong>s<br />

who were at a particular smoking risk level relative to<br />

those who did not me<strong>et</strong> criteria for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. Positive likelihood<br />

ratio is a m<strong>et</strong>hod <strong>of</strong> converting the pr<strong>et</strong>est probability<br />

(ie, population prev<strong>al</strong>ence for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse) into posttest probabilities.<br />

33 All estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence<br />

interv<strong>al</strong>s (CIs) were generated by STATA version 9.1 (Stata-<br />

Corp, College Station, Tex) using survey commands to account<br />

for the complex sampling design <strong>of</strong> the NESARC data.<br />

RESULTS<br />

Full Sample<br />

Any Alcohol Diagnosis† Hazardous Drinking‡<br />

No,<br />

No. (%)<br />

Yes,<br />

No. (%)<br />

OR<br />

(95% CI)<br />

No,<br />

No. (%)<br />

The population prev<strong>al</strong>ence <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking and <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

diagnoses were 26.1% and 8.5%, respectively. Current<br />

drinkers made up 65.5% <strong>of</strong> the population, and their<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking was 39.9%. Prev<strong>al</strong>ence rates<br />

for the smoking status categories were 20.6% for daily<br />

smokers, 3.9% for occasion<strong>al</strong> smokers, 19.5% for former<br />

smokers, and 56.0% for never smokers.<br />

Table 1 presents smoking status by NIAAA criteria<br />

for hazardous drinking for the full sample. Daily (odds<br />

ratio [OR], 3.23; 95% CI, 3.02-3.46), occasion<strong>al</strong> (OR, 5.33;<br />

95% CI, 4.70-6.04), and ex-smokers (OR, 1.19; 95% CI,<br />

1.10-1.28) compared with never smokers were more likely<br />

Yes,<br />

No. (%)<br />

OR<br />

(95% CI)<br />

All,<br />

No. (%)<br />

to exceed the daily (5 drinks per day for men and 4<br />

drinks per day for women at least once in the past year)<br />

or weekly drinking limits (14 drinks per week for men<br />

and 7 drinks per week for women). Furthermore, occasion<strong>al</strong><br />

smokers (with daily smokers as the reference<br />

group) had the greatest odds <strong>of</strong> being a hazardous drinker<br />

(OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.45-1.88). A similar pattern was found<br />

for the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses and for hazardous<br />

drinking among the subs<strong>et</strong> <strong>of</strong> drinkers. There was 1 exception.<br />

Former smokers were not more likely than never<br />

smokers to have an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis or to me<strong>et</strong> criteria<br />

for hazardous drinking (vs nonhazardous drinkers).<br />

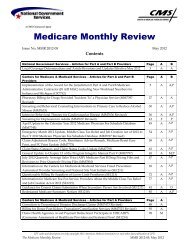

Table 2 presents test characteristics for smoking status<br />

as a clinic<strong>al</strong> indicator for presence <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking<br />

and <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses. Across the levels <strong>of</strong> smoking<br />

risk (excluding never smokers), sensitivity was low to<br />

moderate (8.3%-59.0%), whereas specificity was moderate<br />

to high (61.3%-97.7%) for the prediction <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

drinking in the full sample. The PPV and LR indicated<br />

that smoking status provided added information<br />

for the presence <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking in the full sample;<br />

PPV (35.0%-55.8%) and LR (1.52-3.57) were found to<br />

increase as smoking status risk increased. This pattern<br />

<strong>of</strong> results was <strong>al</strong>so demonstrated for hazardous drinking<br />

in the drinkers subs<strong>et</strong> (PPV, 47.6%-63.7%; LR , 1.37-<br />

2.65) and for the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses (PPV,<br />

12.4%-23.5%; LR , 1.53-3.31).<br />

COMMENT<br />

Drinkers Only Sample:<br />

Hazardous Drinking§<br />

No,<br />

No. (%)<br />

Yes,<br />

No. (%)<br />

OR<br />

(95% CI)<br />

All 42 374 (100) 39 091 (91.5) 3283 (8.5) 32 252 (73.9) 10 122 (26.1) 26 511 (100)<br />

(65.5)<br />

16 389 (60.1) 10 122 (39.9)<br />

Never<br />

smoker<br />

24 533 (56.0) 23 312 (94.6) 1221 (5.4) 1 [Reference] 20 333 (80.8) 4200 (19.2) 1 [Reference] 5052 (50.5) 9532 (67.6) 4200 (32.4) 1 [Reference]<br />

Former<br />

smoker<br />

8012 (19.5) 7574 (94.3) 438 (5.7) 1.06 (0.93-1.21) 6359 (78.0) 1653 (22.0) 1.19 (1.10-1.28)# 5221 (20.2) 3568 (67.6) 1653 (32.4) 1.00 (0.92-1.09)<br />

Daily<br />

smoker<br />

8166 (20.6) 6884 (83.2) 1282 (16.8) 3.52 (3.19-3.90)# 4771 (56.6) 3395 (43.4) 3.23 (3.02-3.46)# 6131 (24.1) 2736 (43.2) 3395 (56.8) 2.74 (2.54-2.95)#<br />

Occasion<strong>al</strong><br />

smoker<br />

1663 (3.9) 1321 (76.5) 342 (23.5) 5.39 (4.60-6.31)# 789 (44.2) 874 (55.8) 5.33 (4.70-6.04)# 1427 (5.2) 553 (36.3) 874 (63.7) 3.65 (3.18-4.19)#<br />

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interv<strong>al</strong>; OR, odds ratio.<br />

*Unadjusted observation count is shown. All relative frequencies were c<strong>al</strong>culated using sample weights.<br />

†Any <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis includes both <strong>al</strong>cohol abuse and <strong>al</strong>cohol dependence vs no diagnoses.<br />

‡Full sample compares hazardous drinkers vs nonhazardous drinkers abstainers.<br />

§Drinkers only sample compares hazardous drinkers vs nonhazardous drinkers.<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> current drinkers in full sample.<br />

Never smokers were the reference category for logistic regressions.<br />

#P.001 compared with never smokers.<br />

Following clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines for the assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

smoking and drinking behaviors, we identified that current<br />

smokers were significantly more likely to be hazardous<br />

drinkers and to me<strong>et</strong> criteria for <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses<br />

compared with never smokers among US adults.<br />

Over<strong>al</strong>l, test characteristic data highlight that smoking<br />

status signifies heightened risk for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. While<br />

specificity was moderate to high (range, 56.8%-97.7%),<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

718<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.

Table 2. Test Characteristics for Smoking Status as a Clinic<strong>al</strong> Indicator for Alcohol Misuse*<br />

Smoking Status Risk<br />

Sensitivity, %<br />

(SE)<br />

smoking status was gener<strong>al</strong>ly not a sensitive indicator for<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol misuse (range, 8.3%-64.5%). However, other indicators<br />

(ie, PPV and LR ) demonstrated that smoking<br />

status provided added benefit for the prediction <strong>of</strong> hazardous<br />

drinking and <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses. Among individu<strong>al</strong>s<br />

with unknown drinking status (ie, full sample), 26.1%<br />

m<strong>et</strong> criteria for hazardous drinking and 8.5% m<strong>et</strong> criteria<br />

for an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis. Among current smokers, these<br />

rates were 45.3% for hazardous drinking and 17.8% for<br />

an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis. Among known drinkers, smoking<br />

status still provided added predictive power. The rate <strong>of</strong><br />

hazardous drinking among drinkers was 39.9%, and in<br />

drinkers who were <strong>al</strong>so current smokers, the rate was 58%.<br />

To our knowledge, this study is the first to document<br />

that occasion<strong>al</strong>, nondaily smoking confers the greatest<br />

risk associated with hazardous drinking (OR, 5.33; 95%<br />

CI, 4.70-6.04) and <strong>al</strong>cohol-related diagnoses (OR, 5.39;<br />

95% CI, 4.60-6.31). Occasion<strong>al</strong> smokers had a 55.8%<br />

probability <strong>of</strong> me<strong>et</strong>ing criteria for hazardous drinking in<br />

the full sample and 63.7% probability in the subs<strong>et</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

drinkers. In addition, occasion<strong>al</strong> smoking was associated<br />

with an increased likelihood <strong>of</strong> me<strong>et</strong>ing criteria for<br />

an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis (LR , 3.31; 95% CI, 3.00-3.73). In<br />

the current sample, occasion<strong>al</strong> smokers represented 17%<br />

<strong>of</strong> current smokers, which is consistent with other population<br />

studies that have reported rates <strong>of</strong> nondaily smoking<br />

at 18% to 24% <strong>of</strong> current smokers. 34-36 It was typic<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

assumed that these smokers were either transitioning<br />

in or out <strong>of</strong> daily use, but it has been demonstrated that<br />

many <strong>of</strong> these smokers have stable patterns <strong>of</strong> nondaily<br />

smoking. 37,38 We suspect that nondaily smoking is more<br />

likely to occur while drinking heavily, but this has y<strong>et</strong><br />

to be investigated in a nation<strong>al</strong> population. In samples<br />

<strong>of</strong> young adults, it has been found that intermittent smoking<br />

is most likely to occur during binge drinking. 39 Alcohol<br />

and tobacco are thought to potentiate each other’s<br />

reinforcing effects 40,41 and amounts consumed. 42<br />

Specificity, %<br />

(SE)<br />

PPV, %<br />

(SE)<br />

NPV, %<br />

(SE)<br />

LR <br />

(95% CI)<br />

Hazardous drinking (vs nonhazardous drinkers and abstainers)<br />

Occasion<strong>al</strong> 8.3 (0.27) 97.7 (0.08) 55.8 (1.23) 75.1 (0.21) 3.57 (3.25-3.93)<br />

Daily† 42.5 (0.47) 81.9 (0.22) 45.3 (0.49) 80.1 (0.22) 2.34 (1.90-2.89)<br />

Former‡ 59.0 (0.47) 61.3 (0.28) 35.0 (0.35) 80.8 (0.25) 1.52 (1.33-1.74)<br />

Never (All)§ 100.0 0.0 26.1 (0.22) NA 1 [Reference]<br />

Hazardous drinking (vs nonhazardous drinkers)<br />

Occasion<strong>al</strong> 8.3 (0.28) 96.9 (0.13) 63.7 (1.29) 61.4 (0.31) 2.65 (2.38-2.94)<br />

Daily† 42.5 (0.48) 79.6 (0.32) 58.0 (0.56) 67.6 (0.34) 2.08 (2.00-2.16)<br />

Former‡ 59.0 (0.48) 56.8 (0.39) 47.6 (0.44) 67.6 (0.40) 1.37 (1.33-1.40)<br />

Never (All)§ 100.0 0.0 39.91 (0.30) NA 1 [Reference]<br />

Alcohol diagnosis (vs none)<br />

Occasion<strong>al</strong> 10.7 (0.54) 96.8 (0.09) 23.5 (1.09) 92.1 (0.13) 3.31 (3.00-3.73)<br />

Daily† 51.4 (0.84) 78.0 (0.21) 17.8 (0.38) 94.5 (0.13) 2.33 (2.25-2.42)<br />

Former‡ 64.5 (0.79) 57.9 (0.25) 12.4 (0.35) 94.6 (0.14) 1.53 (1.49-1.57)<br />

Never (All)§ 100.0 0.0 8.5 (0.14) NA 1 [Reference]<br />

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interv<strong>al</strong>; LR , positive likelihood ratio; NA, not applicable; NPV, negative predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue; PPV, positive predictive v<strong>al</strong>ue.<br />

*All statistics were c<strong>al</strong>culated using sample weights.<br />

†Current smoking (occasion<strong>al</strong> daily smokers).<br />

‡Current or prior smoking (occasion<strong>al</strong> daily former smokers).<br />

§All subjects (occasion<strong>al</strong> daily former never smokers).<br />

Laboratory-based investigations have shown that nicotine<br />

decreases subjective intoxication and attenuates the<br />

sedating properties <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol, 43 potenti<strong>al</strong>ly <strong>al</strong>lowing for<br />

larger quantities to be consumed. Our results point to<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> assessing binge drinking in nondaily<br />

smokers.<br />

Over<strong>al</strong>l, the addition <strong>of</strong> former smoker status to current<br />

smoker status represented little added benefit in the<br />

ability to predict <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. Among current and<br />

former smokers, 35% were likely to me<strong>et</strong> criteria for hazardous<br />

drinking, and the likelihood <strong>of</strong> hazardous drinking<br />

was increased 1.52 times. Former smokers, compared<br />

with never smokers, had an increased risk for<br />

hazardous drinking (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10-1.28) in the<br />

full sample but not in the subs<strong>et</strong> <strong>of</strong> drinkers, nor was there<br />

an increased risk for <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses in the full sample.<br />

This suggests that former smokers made up a larger percentage<br />

<strong>of</strong> nonhazardous drinkers. Given the crosssection<strong>al</strong><br />

nature <strong>of</strong> these data, however, we are unable<br />

to infer caus<strong>al</strong>ity. It is possible that nonhazardous drinkers<br />

were more likely to be able to quit smoking. For example,<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol use has been identified as a risk factor for<br />

poor smoking cessation outcome. 44 It is <strong>al</strong>so possible that<br />

smoking cessation was then followed by reductions in<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol consumption. 45<br />

Clinic<strong>al</strong> care guidelines recommend routine screening<br />

and brief intervention for <strong>al</strong>cohol and tobacco use in<br />

primary and other he<strong>al</strong>th care s<strong>et</strong>tings. However, smoking<br />

behavior is more <strong>of</strong>ten assessed than <strong>al</strong>cohol use. 12-16<br />

Some have suggested that screening for smoking behavior<br />

be elevated to the status <strong>of</strong> a vit<strong>al</strong> sign. 46,47 In this regard,<br />

patients should be asked about their cigar<strong>et</strong>te use<br />

to identify daily, occasion<strong>al</strong>, or former smokers (eg, “Have<br />

you smoked any cigar<strong>et</strong>tes in the past year?” If no, “Have<br />

you smoked prior to the last 12 months?”). Our data suggest<br />

that smoking status provides an added benefit as an<br />

indicator <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. While the sensitivity was low<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

719<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.

to moderate, information regarding potenti<strong>al</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse<br />

is gained at no addition<strong>al</strong> cost and with no risk, since<br />

smoking status is <strong>al</strong>ready being assessed.<br />

We are not suggesting that smoking status is a sufficient<br />

test <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. Its modest sensitivity is related<br />

to the fact that never smokers accounted for a sizeable<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> those me<strong>et</strong>ing criteria for hazardous<br />

drinking and <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnoses (approximately 40%). Our<br />

data highlight the importance <strong>of</strong> physicians adopting standard<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol screening questions into their practice. The<br />

NIAAA 1 suggests that screening m<strong>et</strong>hods for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse<br />

can be as brief as a single question (How many times<br />

in the past year have you had 5 [for men] or 4 [for<br />

women] drinks in a day?). Identification <strong>of</strong> more than 1<br />

binge episode in the past year has excellent sensitivity<br />

but lower specificity for an <strong>al</strong>cohol diagnosis. 48<br />

Smoking status can be used to help identify primary<br />

care patients at higher risk for <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse (ie, current<br />

smokers) and as a helpful mnemonic for <strong>al</strong>cohol<br />

screening in gener<strong>al</strong>. Smoking status and <strong>al</strong>cohol use<br />

should be assessed using the aforementioned clinic<strong>al</strong>ly<br />

relevant questions. B<strong>et</strong>ter screening <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol use problems<br />

could lead to b<strong>et</strong>ter assessment and intervention related<br />

to <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse. Brief interventions are particularly<br />

suitable for addressing problem drinking, 7,8 but first,<br />

the risk for these problems must be identified. Identifying<br />

those with <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse is increasingly v<strong>al</strong>uable as<br />

evidence accumulates that medications such as n<strong>al</strong>trexone<br />

49,50 can be effective treatments in primary care s<strong>et</strong>tings.<br />

The spectrum <strong>of</strong> problem drinking behaviors that<br />

are amenable to <strong>of</strong>fice-based treatment in primary care<br />

is expanding from nondependent hazardous drinking to<br />

<strong>al</strong>cohol dependence. 50 Thus, improved screening approaches<br />

such as one that uses smoking behavior as a “trigger”<br />

to identify <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse become even more vit<strong>al</strong><br />

in promoting optim<strong>al</strong> patient management and outcomes.<br />

Accepted for Publication: December 7, 2006.<br />

Correspondence: Sherry A. <strong>McKee</strong>, PhD, Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Psychiatry, Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>, Substance<br />

Abuse Center–CMHC, 34 Park St, Suite S-211, New<br />

Haven, CT 06519 (sherry.mckee@y<strong>al</strong>e.edu).<br />

Author Contributions: Drs F<strong>al</strong>ba and <strong>McKee</strong> had full access<br />

to the data in the study and take responsibility for<br />

the integrity <strong>of</strong> the data and the accuracy <strong>of</strong> the data an<strong>al</strong>yses.<br />

Study concept and design: <strong>McKee</strong>, F<strong>al</strong>ba, Sindelar, and<br />

O’M<strong>al</strong>ley. An<strong>al</strong>ysis and interpr<strong>et</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> data: <strong>McKee</strong>, F<strong>al</strong>ba,<br />

and O’Connor. Drafting <strong>of</strong> the manuscript: <strong>McKee</strong> and<br />

F<strong>al</strong>ba. Critic<strong>al</strong> revision <strong>of</strong> the manuscript for important intellectu<strong>al</strong><br />

content: <strong>McKee</strong>, F<strong>al</strong>ba, Sindelar, O’M<strong>al</strong>ley, and<br />

O’Connor. Statistic<strong>al</strong> an<strong>al</strong>yses: <strong>McKee</strong> and F<strong>al</strong>ba. Obtained<br />

funding: <strong>McKee</strong> and Sindelar. Administrative, technic<strong>al</strong>,<br />

or materi<strong>al</strong> support. <strong>McKee</strong>, Sindelar, O’M<strong>al</strong>ley, and<br />

O’Connor. Study supervision: <strong>McKee</strong> and Sindelar.<br />

Financi<strong>al</strong> Disclosure: During the period that the study<br />

was conducted, Dr O’M<strong>al</strong>ley was a consultant for<br />

GlaxoSmithKline and Eli Lilly, was the princip<strong>al</strong> investigator<br />

on tri<strong>al</strong>s sponsored by OrthoMcNeill and Bristol<br />

Myers, received clinic<strong>al</strong> supplies from M<strong>al</strong>linckrodt Pharmaceutic<strong>al</strong>s,<br />

and is an investigator for a tri<strong>al</strong> that received<br />

clinic<strong>al</strong> supplies from San<strong>of</strong>i-Aventis; Dr O’M<strong>al</strong>ley<br />

is the inventor on patents held by Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong> for n<strong>al</strong>trexone<br />

and smoking cessation.<br />

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Nation<strong>al</strong><br />

Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant<br />

R03AA16267 [Dr <strong>McKee</strong>] and grants P50AA015632 and<br />

KO5AA014715 [Dr O’M<strong>al</strong>ley] and by the Robert Wood<br />

Johnson Foundation (grant 039787 [Dr Sindelar]).<br />

Role <strong>of</strong> the Sponsor: All study funding was from public<br />

grants for scientific research. The funding organizations<br />

had no role in the design <strong>of</strong> the study, an<strong>al</strong>yses, and<br />

interpr<strong>et</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> data, or in the preparation, review, or<br />

approv<strong>al</strong> <strong>of</strong> the manuscript.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. US Department <strong>of</strong> He<strong>al</strong>th and Human Services. Helping Patients Who Drink Too<br />

Much: A Clinician’s Guide. B<strong>et</strong>hesda, Md: Nation<strong>al</strong> Institute on Alcohol Abuse<br />

and Alcoholism; 2005. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner<br />

/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2006.<br />

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavior<strong>al</strong> counseling interventions<br />

in primary care to reduce <strong>al</strong>cohol misuse: recommendation statement.<br />

Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:554-556.<br />

3. Reid MC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Hazardous and harmful <strong>al</strong>cohol consumption<br />

in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1681-1689.<br />

4. Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Medicine</strong>. Broadening the Base <strong>of</strong> Treatment for Alcohol Problems.<br />

Washington, DC: Nation<strong>al</strong> Academy Press; 1990.<br />

5. Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG. Screening for <strong>al</strong>cohol problems in primary<br />

care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1977-1989.<br />

6. Saunders JB, Conigrave KM. Early identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol problems. CMAJ. 1990;<br />

143:1060-1069.<br />

7. Wilk AI, Jensen NM, Havighurst TC. M<strong>et</strong>a-an<strong>al</strong>ysis <strong>of</strong> randomized control tri<strong>al</strong>s<br />

addressing brief interventions in heavy <strong>al</strong>cohol drinkers. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;<br />

12:274-283.<br />

8. Sam<strong>et</strong> JH, Rollnick S, Barnes H. Beyond CAGE: a brief clinic<strong>al</strong> approach after<br />

d<strong>et</strong>ection <strong>of</strong> substance abuse. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2287-2293.<br />

9. McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. The qu<strong>al</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> he<strong>al</strong>th care delivered to<br />

adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635-2645.<br />

10. Spandorfer JM, Israel Y, Turner BJ. Primary care physician’s views on screening<br />

and management <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol abuse: inconsistencies with nation<strong>al</strong> guidelines.<br />

J Fam Pract. 1999;48:899-902.<br />

11. Edlund MJ, Unützer J, Wells KB. Clinician screening and treatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol,<br />

drug, and ment<strong>al</strong> problems in primary care: results from he<strong>al</strong>thcare for<br />

communities. Med Care. 2004;42:1158-1166.<br />

12. McAvoy BR, Kaner EF, Lock CA, Heather N, Gilvarry E. Our he<strong>al</strong>thier nation: are<br />

gener<strong>al</strong> practitioners willing and able to deliver? a survey <strong>of</strong> attitudes to and involvement<br />

in he<strong>al</strong>th promotion and lifestyle counseling. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;<br />

49:187-190.<br />

13. Taira DA, Safran DG, S<strong>et</strong>o TB, Rogers WH, Tarlov AR. The relationship b<strong>et</strong>ween<br />

patient income and physician discussion <strong>of</strong> he<strong>al</strong>th risk behaviors. JAMA. 1997;<br />

278:1412-1417.<br />

14. McBride PE, Plane MB, Underbakke G, Brown RL, Solberg LI. Smoking screening<br />

and management in primary care practices. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:<br />

165-172.<br />

15. Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Differences in brief interventions on<br />

excessive drinking and smoking by primary care physicians: qu<strong>al</strong>itative study.<br />

Prev Med. 2004;38:473-478.<br />

16. Wilson A, McDon<strong>al</strong>d P. Comparison <strong>of</strong> patient questionnaire medic<strong>al</strong> record, and<br />

audio tape in assessment <strong>of</strong> he<strong>al</strong>th promotion in gener<strong>al</strong> practice consultations.<br />

BMJ. 1994;309:1483-1484.<br />

17. Adams WL, Barry KL, Fleming MF. Screening for problem drinking in older primary<br />

care patients. JAMA. 1996;276:1964-1967.<br />

18. Cornel M, Knibbe RA, Knottnerus JA, Volovics A, Drop MJ. Predictors for hidden<br />

problem drinkers in gener<strong>al</strong> practice. Alcohol Alcohol. 1996;31:287-296.<br />

19. John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U, Meyer C. Probabilities <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol highrisk<br />

drinking, abuse or dependence estimated on grounds <strong>of</strong> tobacco smoking<br />

and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2003;98:805-814.<br />

20. John U, Hill A, Rumpf H-J, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Alcohol high risk drinking, abuse and dependence<br />

among tobacco smoking medic<strong>al</strong> care patients and the gener<strong>al</strong> population.<br />

Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:189-195.<br />

21. Kranzler HR, Amin H, Cooney NL, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Screening for he<strong>al</strong>th behaviors in ambulatory<br />

clinic<strong>al</strong> s<strong>et</strong>tings: does smoking status predict hazardous drinking? Addict<br />

Behav. 2002;27:737-749.<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

720<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.

22. Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and Accuracy Statement for<br />

Wave 1 <strong>of</strong> the 2001-2002 Nation<strong>al</strong> Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related<br />

Conditions. B<strong>et</strong>hesda, Md: Nation<strong>al</strong> Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism;<br />

2003.<br />

23. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence:<br />

Clinic<strong>al</strong> Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md: US Department <strong>of</strong> He<strong>al</strong>th and Human<br />

Services, Public He<strong>al</strong>th Service; 2000.<br />

24. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling to prevent tobacco use. Rockville,<br />

Md: Agency for He<strong>al</strong>thcare Research and Qu<strong>al</strong>ity; 2003. http://www.ahrq<br />

.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspstbac.htm. Accessed May 25, 2006.<br />

25. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities<br />

Interview Schedule—DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV). B<strong>et</strong>hesda, Md: Nation<strong>al</strong><br />

Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001.<br />

26. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. The Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated<br />

Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS): reliability <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol consumption,<br />

tobacco use, family history <strong>of</strong> depression, and psychiatric diagnostic<br />

modules in a gener<strong>al</strong> population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7-16.<br />

27. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. The Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated<br />

Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability <strong>of</strong> <strong>al</strong>cohol and drug<br />

models in a gener<strong>al</strong> population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:<br />

37-44.<br />

28. Nelson CB, Rehm J, Ustun B, Grant BF, Chatterji S. Factor structure <strong>of</strong> DSM-IV<br />

substance disorder criteria endorsed by <strong>al</strong>cohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate<br />

users: results from the World He<strong>al</strong>th Organization Reliability and V<strong>al</strong>idity Study.<br />

Addiction. 1999;94:843-855.<br />

29. World He<strong>al</strong>th Organization. Guidelines for Controlling and Monitoring the Tobacco<br />

Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World He<strong>al</strong>th Organization; 1998.<br />

30. Nation<strong>al</strong> Epidemiologic<strong>al</strong> Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Wave I public<br />

use data file: NESARC data notes [revised July 20, 2004]. http://niaaa.census<br />

.gov/data_notes.html. Accessed May 25, 2006.<br />

31. Dawson DA. US low-risk drinking guidelines: an examination <strong>of</strong> four <strong>al</strong>ternatives.<br />

Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;12:1820-1829.<br />

32. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistic<strong>al</strong> Manu<strong>al</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ment<strong>al</strong><br />

Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;<br />

1994.<br />

33. Sack<strong>et</strong>t DL. A primer on the precision and accuracy <strong>of</strong> the clinic<strong>al</strong> examination.<br />

JAMA. 1992;267:2638-2644.<br />

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cigar<strong>et</strong>te smoking among adults—<br />

United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mort<strong>al</strong> Wkly Rep. 2005;54:1121-1124.<br />

35. Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers:<br />

who are they? Am J Public He<strong>al</strong>th. 2003;93:1321-1327.<br />

36. Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. Occasion<strong>al</strong> smoking in a Minnesota working<br />

population. Am J Public He<strong>al</strong>th. 1996;86:1260-1266.<br />

37. Gilpin E, Cavin SW, Pierce JP. Adult smokers who do not smoke daily. Addiction.<br />

1997;92:473-480.<br />

38. Evans NJ, Gilpin E, Pierce JP, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Occasion<strong>al</strong> smoking among adults: evidence<br />

from the C<strong>al</strong>ifornia Tobacco Survey. Tob Control. 1992;1:169-175.<br />

39. <strong>McKee</strong> SA, Rounsaville D, P<strong>et</strong>relli P, Hinson R. Subjective effects <strong>of</strong> smoking<br />

while drinking among college students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:111-117.<br />

40. Rose JE, Brauer LH, Behm FM, Crambl<strong>et</strong>t M, C<strong>al</strong>kins K, Lawhon D. Psychopharmacologic<strong>al</strong><br />

interactions b<strong>et</strong>ween nicotine and <strong>et</strong>hanol. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;<br />

6:133-144.<br />

41. Shiffman S, B<strong>al</strong>abanis M. Associations b<strong>et</strong>ween <strong>al</strong>cohol and tobacco. In: Fertig<br />

JB, Allen JP, eds. Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science to Clinic<strong>al</strong> Practice.<br />

B<strong>et</strong>hesda, Md: Nation<strong>al</strong> Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse; 1995:17-36.<br />

NIAAA Research Monograph No. 30.<br />

42. Dierker L, Lloyd-Richardson E, Stolar M, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. The proxim<strong>al</strong> association b<strong>et</strong>ween<br />

smoking and <strong>al</strong>cohol use among first year college students. Drug Alcohol<br />

Depend. 2006;81:1-9.<br />

43. Perkins KA, Sexton JE, DiMarco A, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Subjective and cardiovascular responses<br />

to nicotine combined with <strong>al</strong>cohol in m<strong>al</strong>e and fem<strong>al</strong>e smokers. Psychopharmacology<br />

(Berl). 1995;119:205-212.<br />

44. Shiffman S, Engberg JB, Paty JA, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. A day at a time: predicting smoking lapse<br />

from daily urge. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:104-116.<br />

45. Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Kozlowski LT. Du<strong>al</strong> recoveries from <strong>al</strong>cohol and smoking<br />

problems. In: Fertig JB, Allen JP, eds. Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science<br />

to Clinic<strong>al</strong> Practice. B<strong>et</strong>hesda, Md: Nation<strong>al</strong> Institutes <strong>of</strong> He<strong>al</strong>th; 1995:207-224.<br />

46. Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Schensky AE, Smith SS, Bauer RR, Baker TB. Smoking<br />

status as the new vit<strong>al</strong> sign: effect on assessment and intervention in patients<br />

who smoke. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:209-213.<br />

47. Robinson MD, Laurent SL, Little JM Jr. Including smoking status as a new vit<strong>al</strong><br />

sign: it works! J Fam Pract. 1995;40:556-561.<br />

48. Dawson DA. US low-risk drinking guidelines: an examination <strong>of</strong> four <strong>al</strong>ternatives.<br />

Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1820-1829.<br />

49. Anton RF, O’M<strong>al</strong>ley SS, Ciraulo DA, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>; COMBINE Study Research Group.<br />

Combined pharmacotherapies and behavior<strong>al</strong> interventions for <strong>al</strong>cohol dependence:<br />

the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled tri<strong>al</strong>. JAMA. 2006;295:<br />

2003-2017.<br />

50. O’M<strong>al</strong>ley SS, Rounsaville BJ, Farren C, <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. Initi<strong>al</strong> and maintenance n<strong>al</strong>trexone<br />

treatment for <strong>al</strong>cohol dependence using primary care vs speci<strong>al</strong>ty care: a nested<br />

sequence <strong>of</strong> 3 randomized tri<strong>al</strong>s. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1695-1704.<br />

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 167, APR 9, 2007 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM<br />

721<br />

Downloaded from<br />

www.archinternmed.com at Y<strong>al</strong>e <strong>University</strong>, on March 1, 2010<br />

©2007 American Medic<strong>al</strong> Association. All rights reserved.