Azathioprine and chlorambucil: mechanism of action and use in ...

Azathioprine and chlorambucil: mechanism of action and use in ...

Azathioprine and chlorambucil: mechanism of action and use in ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong>: <strong>mechanism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>action</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

dermatology<br />

Dr. Fiona Bateman BVSc MACVSc<br />

Introduction<br />

Systemic immune moderators have been <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> both human <strong>and</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary dermatology for the treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

a wide variety <strong>of</strong> immune mediated <strong>and</strong> allergic conditions. While their <strong>use</strong> is <strong>of</strong>f label (even with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

human field), a large amount <strong>of</strong> evidence attests to their safety <strong>and</strong> efficacy. Both azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong> have been <strong>use</strong> as s<strong>in</strong>gle agent or, more commonly, <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy <strong>of</strong> a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

dermatological conditions.<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong><br />

History<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> was first developed as an anti-rejection drug for renal transplantation <strong>and</strong> was first<br />

<strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with cortisone for this purpose <strong>in</strong> 1962. The discovery <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e is one <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

examples <strong>of</strong> what is now termed ‘rational drug design’. George Hitch<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> Gerturde Elion, researchers at<br />

Burroughs Wellcome Research Laboratories (now GlaxoSmithKl<strong>in</strong>e) were pioneers <strong>in</strong> drug development <strong>and</strong><br />

attempted to identify cellular <strong>and</strong> molecular targets for which they then developed targeted drugs. One such<br />

drug was 6-MP (6-mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e), the precursor <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

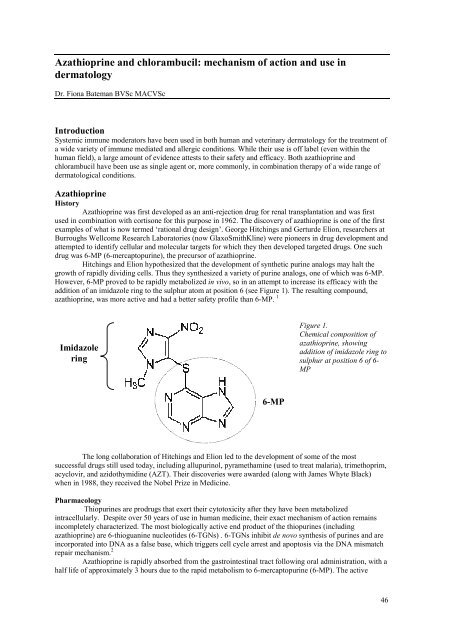

Hitch<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> Elion hypothesized that the development <strong>of</strong> synthetic pur<strong>in</strong>e analogs may halt the<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> rapidly divid<strong>in</strong>g cells. Thus they synthesized a variety <strong>of</strong> pur<strong>in</strong>e analogs, one <strong>of</strong> which was 6-MP.<br />

However, 6-MP proved to be rapidly metabolized <strong>in</strong> vivo, so <strong>in</strong> an attempt to <strong>in</strong>crease its efficacy with the<br />

addition <strong>of</strong> an imidazole r<strong>in</strong>g to the sulphur atom at position 6 (see Figure 1). The result<strong>in</strong>g compound,<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, was more active <strong>and</strong> had a better safety pr<strong>of</strong>ile than 6-MP. 1<br />

Imidazole<br />

r<strong>in</strong>g<br />

6-MP<br />

Figure 1.<br />

Chemical composition <strong>of</strong><br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, show<strong>in</strong>g<br />

addition <strong>of</strong> imidazole r<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

sulphur at position 6 <strong>of</strong> 6-<br />

MP<br />

The long collaboration <strong>of</strong> Hitch<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> Elion led to the development <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

successful drugs still <strong>use</strong>d today, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g allupur<strong>in</strong>ol, pyrametham<strong>in</strong>e (<strong>use</strong>d to treat malaria), trimethoprim,<br />

acyclovir, <strong>and</strong> azidothymid<strong>in</strong>e (AZT). Their discoveries were awarded (along with James Whyte Black)<br />

when <strong>in</strong> 1988, they received the Nobel Prize <strong>in</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Pharmacology<br />

Thiopur<strong>in</strong>es are prodrugs that exert their cytotoxicity after they have been metabolized<br />

<strong>in</strong>tracellularly. Despite over 50 years <strong>of</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> human medic<strong>in</strong>e, their exact <strong>mechanism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>action</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

<strong>in</strong>completely characterized. The most biologically active end product <strong>of</strong> the thiopur<strong>in</strong>es (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e) are 6-thioguan<strong>in</strong>e nucleotides (6-TGNs) . 6-TGNs <strong>in</strong>hibit de novo synthesis <strong>of</strong> pur<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> are<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to DNA as a false base, which triggers cell cycle arrest <strong>and</strong> apoptosis via the DNA mismatch<br />

repair <strong>mechanism</strong>. 2<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> is rapidly absorbed from the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract follow<strong>in</strong>g oral adm<strong>in</strong>istration, with a<br />

half life <strong>of</strong> approximately 3 hours due to the rapid metabolism to 6-mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e (6-MP). The active<br />

46

metabolites have a much longer half life, which allows for once daily dos<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> is extensively<br />

metabolized (Figure 2), with only 2% excreted unchanged <strong>in</strong> the ur<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> is reduced through non-enzymatic degradation to 6-MP <strong>in</strong> vivo. This process occurs<br />

through nucleophillic attack by sulphahydryl compounds present <strong>in</strong> erythrocytes <strong>and</strong> body tissues. 3 6-MP is<br />

then metabolized by one <strong>of</strong> four pathways:<br />

1. Hypoxanth<strong>in</strong>e-guan<strong>in</strong>e phophoribosyl transferase (HGPRT) – conversion to 6-thioimos<strong>in</strong>e-5’monophosphate<br />

(TIMP).<br />

2. Thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyltransferase (TPMT) – catalyses S-methylation to 6-methyl mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e<br />

(<strong>in</strong>active compound)<br />

3. Xanth<strong>in</strong>e oxidase (XO) – catalyses oxidation to 6-thiouric acid (<strong>in</strong>active compound)<br />

4. Aldehyde oxidase (AO) – conversion to 6-TGN hydroxylated metabolites (<strong>in</strong>active compound)<br />

The enzymatic competition for the 6-MP substrate is vigorous, with the effects <strong>of</strong> XO <strong>and</strong> AO activity<br />

leav<strong>in</strong>g only 16% <strong>of</strong> the total dose <strong>of</strong> 6-MP for systemic distribution. 4 Note this does not <strong>in</strong>clude TPMT<br />

activity, which will decrease the amount <strong>of</strong> 6-MP converted to TIMP further. The compet<strong>in</strong>g pathways are<br />

important <strong>in</strong> that block<strong>in</strong>g a metabolic pathway <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the degradation <strong>of</strong> 6-MP (for example, through<br />

the <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> a xanthane oxidase <strong>in</strong>hibitor such as allopur<strong>in</strong>ol, or through low endogenous TPMT activity) can<br />

dramatically <strong>in</strong>crease the available amount <strong>of</strong> 6-MP to be converted to active 6-TGNs, thereby drastically<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the risk <strong>of</strong> severe adverse effects.<br />

Once 6-MP is converted to TIMP, TIMP is then converted to 6-thioguanos<strong>in</strong>e-5’monophopshate<br />

(TGMP) <strong>in</strong> a 2 step process. TGMP is further metabolized through a series <strong>of</strong> reductases <strong>and</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ases to form<br />

the 6-TGN metabolite, deoxy-6-thioguanos<strong>in</strong>e-5’-triphosphate (dGS). dGS is then <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to DNA as<br />

a false base <strong>and</strong> triggers cell cycle arrest <strong>and</strong> apoptosis.<br />

Figure 2. Metabolism <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e to active 6-TGN metabolites.<br />

Key: 6-thioguan<strong>in</strong>e nucleotides (6-TGN), aldehyde oxidase (AO), xanth<strong>in</strong>e oxidase (XO), azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e<br />

(AZA), 6-methyl mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e (6-MMP), 6-mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e (6-MP), hypoxanth<strong>in</strong>e-guan<strong>in</strong>e<br />

phophoribosyl transferase (HGPRT), 6-thioimos<strong>in</strong>e-5’-monophosphate (TIMP), methyl-6thio<strong>in</strong>os<strong>in</strong>e<br />

monophosphate (MeTIMP), Thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyltransferase (TPMT) , to 6-thioguanos<strong>in</strong>e-<br />

5’monophopshate (TGMP)<br />

Mechanism <strong>of</strong> <strong>action</strong><br />

The 6-TGN active metabolites disrupt the function <strong>of</strong> endogenous pur<strong>in</strong>es. While all cells are<br />

theoretically affected by this unstable base <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to DNA, RNA <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>s, lymphocytes are<br />

preferentially targeted by thiopur<strong>in</strong>es. Lymphocytes rely on de novo synthesis <strong>of</strong> pur<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> lack a pur<strong>in</strong>e<br />

salvage pathway. Thus they are most affected by the <strong>action</strong> <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e on pur<strong>in</strong>e synthesis <strong>and</strong><br />

metabolism. 5 <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> has a wide range <strong>of</strong> short <strong>and</strong> long term effects on the immune system, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

- reversible reduction <strong>of</strong> monocyte numbers <strong>in</strong> circulation <strong>and</strong> tissues 6<br />

- impaired synthesis <strong>of</strong> gamma globul<strong>in</strong> (IgM, IgG) <strong>in</strong> patients with rheumatoid<br />

disorders 7<br />

- long term immunosuppression decreases the number <strong>of</strong> cutaneous Langerhans cells 8<br />

- impaired responses <strong>of</strong> helper T cell dependent B cells 9<br />

- impaired function <strong>of</strong> T suppressor cells 9<br />

- impaired T cell lymphocyte function <strong>and</strong> IL-2 production 10<br />

47

- <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>action</strong> with Rac1, a triphosphate b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> on T lymphocytes that medicates<br />

a costimulatory signal for T cell activation. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibits Rac1, block<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

costimulatory signal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>duc<strong>in</strong>g Fas-associated apoptosis 11 , 12<br />

In addition to the effects <strong>of</strong> 6-TGN metabolites, pur<strong>in</strong>e de novo synthesis is also <strong>in</strong>hibited by<br />

methyl-6-thio<strong>in</strong>os<strong>in</strong>e monophosphate (Me-TIMP). Inhibition <strong>of</strong> de novo pur<strong>in</strong>e synthesis contributes to<br />

immunosuppression <strong>and</strong> blocks proliferation <strong>of</strong> various lymphocyte l<strong>in</strong>es, thereby contribut<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

cytotoxic <strong>action</strong> <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e. 13<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>and</strong> TMPT activity<br />

TMPT is the predom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong>activation pathway <strong>of</strong> thiopur<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> haemopoetic cells. 13 The end product<br />

<strong>of</strong> AZA degradation through the TMPT pathway is 6-methyl mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e (6-MMP), an <strong>in</strong>active <strong>and</strong> nontoxic<br />

molecule. Erythrocyte levels <strong>of</strong> TPMT have been found to correlate well with levels <strong>in</strong> lymphocytes,<br />

platelets, kidney <strong>and</strong> liver cells <strong>in</strong> humans. 1 TMPT activity is genetically controlled, with several<br />

polymorphisms identified <strong>in</strong> humans. In a recent study <strong>of</strong> over 3000 patients, approximately 80% had<br />

normal TPMT activity 9% had above normal enzymatic activity <strong>and</strong> 10% had low TPMT activity.<br />

Additionally, 0.45% <strong>of</strong> patients had no detectable TPMT activity. 14 Low activity is associated with an<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> leukopenia, <strong>in</strong>termediate levels are associated with the development <strong>of</strong> late onset<br />

leukopenia <strong>and</strong> high TPMT activity results is less immunosuppression by azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e. Determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> pretreatment<br />

TPMT level has been advocated <strong>in</strong> human medic<strong>in</strong>e to detect patients at risk for early onset<br />

neutropenia (i.e. those with no or low TPMT activity). However the significance <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity <strong>in</strong> dogs<br />

<strong>and</strong> cats rema<strong>in</strong>s poorly characterized.<br />

Studies <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity <strong>in</strong> the dog <strong>in</strong>dicate that average levels <strong>of</strong> erythrocyte TPMT activity are<br />

similar to that <strong>in</strong> humans, but that marked variation exists <strong>in</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity when<br />

compared to the human studies. 15-17 Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, no dog was found with deficient TPMT activity<br />

(comparable to the human ‘low activity’ group) <strong>and</strong> that the 6 <strong>of</strong> 299 dogs <strong>in</strong> one study that experienced<br />

marked leukopenia associated with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>use</strong>, all <strong>of</strong> these dogs had <strong>in</strong>termediate to high TPMT<br />

activity. 16 This suggests that there exists a different <strong>mechanism</strong> by which azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e-<strong>in</strong>duced<br />

myelotoxicity is <strong>in</strong>duced <strong>in</strong> the can<strong>in</strong>e population when compared with humans.<br />

In cats, average levels <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity were significantly lower than both humans <strong>and</strong> dogs, <strong>and</strong> cats<br />

also displayed large <strong>in</strong>dividual variations <strong>in</strong> the level <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity. 18 This is consistent with the high<br />

level <strong>of</strong> myelosuppression <strong>and</strong> leukopenia seen when azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e is adm<strong>in</strong>istered to cats, <strong>and</strong> further<br />

supports the recommendation that azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e not be <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> this species.<br />

Studies <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> the horse are limited, but TPMT activity is reported to be lower than both<br />

dogs <strong>and</strong> cats. 19 Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, marked myelosuppression (which would be expected to be marked given the<br />

low TPMT activity) is <strong>in</strong>frequently seen <strong>in</strong> the horse. 20 This may <strong>in</strong>dicate that erythrocyte TPMT activity<br />

may not correlate to TPMT activity <strong>in</strong> other tissues( particularly the liver) or that other degradation<br />

pathways, such as XO or AO may be more important for the metabolism <strong>of</strong> 6-Mp to <strong>in</strong>active compounds <strong>in</strong><br />

this species.<br />

Indications <strong>in</strong> dermatology<br />

Dermatologic <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong>f label <strong>in</strong> both human <strong>and</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature.<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> has been <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> dermatological conditions for over 50 years, <strong>and</strong> its <strong>use</strong> is supported by<br />

numerous studies, case reports <strong>and</strong> expert op<strong>in</strong>ion. However, by the strictest evidence-based medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards, the support for its <strong>use</strong> is not as strong as for a variety <strong>of</strong> newer medications, such <strong>and</strong><br />

cyclospor<strong>in</strong>e. 1<br />

48

Human<br />

Table 1. Selected dermatologic diseases where azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e has shown to be <strong>of</strong> benefit<br />

Immunobullous disease Eczema<br />

Bullous pemphigoid Contact dermatitis<br />

Pemphigoid Photodermatitis<br />

Cicatricial pemphigoid Act<strong>in</strong>ic reticuloid<br />

Juvenile pemphigus Chronic act<strong>in</strong>ic dermatitis<br />

Pemphigus foliaceous Other<br />

Pemphigus vulgaris Erythema multiforme<br />

Paraneoplastic pemphigus Cutaneous lupus erythematosus<br />

Pemphigus erythematosus Lichen planus<br />

Eczematous diseases Cutaneous vasculitis<br />

Psoriasis Graft-versus-host disease<br />

Atopic dermatitis<br />

Adapted from Patel, et. al. 1<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Table 2. Selected dermatologic diseases where azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e may be <strong>of</strong> benefit<br />

Pemphigus foliaceous 21, 22 Lupoid onychitis ** 23<br />

Pemphigus vulgaris 21, 22 Uveodermatologic syndrome<br />

Superficial pemphigus complex 21, 22 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita 24<br />

Systemic lupus erythematosus 22 Perianal fistula **<br />

Vesicular cutaneous lupus erythematosus 25 Erythema multiforme 26<br />

Cutaneous reactive histiocytosis ** 27<br />

Idiopathic sterile granuloma <strong>and</strong><br />

? Atopic dermatitis** 28<br />

pyogranuloma 22<br />

** <strong>in</strong>dicates that other forms <strong>of</strong> drug therapy are the gold st<strong>and</strong>ard for treatment <strong>of</strong> this condition, but<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e may be <strong>of</strong> benefit <strong>in</strong> refractory cases<br />

Adverse effects<br />

Haematologic<br />

Cytopenias <strong>and</strong> severe bone marrow suppression have been reported <strong>in</strong> both the human <strong>and</strong><br />

veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature, <strong>and</strong> may occur weeks to months after <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g treatment. Humans may suffer from<br />

bone marrow suppression years after <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g therapy, as steady state levels <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the blood<br />

may take month to years to achieve. 2 While neutropenia is the most common cytopenia noted, anaemia <strong>and</strong><br />

thrombocytopenia may also occur. 29 TPMT genotype test<strong>in</strong>g is advocated <strong>in</strong> human medic<strong>in</strong>e to identify<br />

those <strong>in</strong>dividuals at risk for develop<strong>in</strong>g acute or delayed onset neutropenia. While TPMT activity has been<br />

measured <strong>in</strong> dogs, cats <strong>and</strong> horses, its relevance to the development <strong>of</strong> adverse effects is unknown.<br />

While pretreatment TPMT activity is a <strong>use</strong>ful <strong>in</strong>dicator <strong>of</strong> susceptible <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> humans,<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous hematological monitor<strong>in</strong>g is still m<strong>and</strong>atory <strong>in</strong> humans <strong>and</strong> animals. Leukopenia <strong>in</strong>duced by<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, while potentially life threaten<strong>in</strong>g, is usually reversible with discont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> treatment or a<br />

dose reduction.<br />

Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

Na<strong>use</strong>a <strong>and</strong> vomit<strong>in</strong>g, though widely reported <strong>in</strong> the human literature, are uncommonly encountered<br />

<strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. Symptoms usually occur <strong>in</strong> the first few weeks <strong>of</strong> therapy <strong>and</strong> may self resolve.<br />

Adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e with food or <strong>in</strong> a divided dose may help to reduce the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong><br />

gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al upset. 2<br />

Hepatotoxicity is the second most common gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al side effect <strong>and</strong> is <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> TPMT<br />

activity. 30 In most cases, hepatotoxicity is an unpredictable side effect <strong>and</strong> the <strong>mechanism</strong> <strong>of</strong> hepatocyte<br />

<strong>in</strong>jury is poorly characterized. In dogs, elevation <strong>of</strong> alkal<strong>in</strong>e phosphatase, alan<strong>in</strong>e am<strong>in</strong>otransferase <strong>and</strong><br />

bilirub<strong>in</strong> may be transient, <strong>in</strong> other cases they may be persistent <strong>and</strong> progressive lead<strong>in</strong>g to hepatic failure<br />

<strong>and</strong> death. In a small pilot study us<strong>in</strong>g azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e for the treatment <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e atopic dermatitis, serum levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> alan<strong>in</strong>e am<strong>in</strong>otransferase <strong>and</strong> alkal<strong>in</strong>e phosphatase rose <strong>in</strong> 83% <strong>of</strong> dogs by the second week <strong>of</strong> daily<br />

treatment, <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs <strong>of</strong> hepatitis were reported <strong>in</strong> 3 <strong>of</strong> 12 dogs (25%) necessitat<strong>in</strong>g the need for<br />

removal from the study. 28<br />

49

Pancreatitis has been associated with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> both the human 1 <strong>and</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

literature. 31 In humans, pancreatitis mostly occurs <strong>in</strong> patients with concurrent gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al disorders. In<br />

dogs, azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e is commonly <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy (usually with corticosteroids) so a direct causal<br />

relationship may be difficult to determ<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections<br />

Long term immunosuppression has been associated with an <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> the development <strong>of</strong><br />

opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections. This may occur even <strong>in</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong> leukopenia <strong>and</strong> herpes simplex, herpes zoster<br />

<strong>and</strong> verrucae have been reported at a higher <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>in</strong> humans receiv<strong>in</strong>g comb<strong>in</strong>ation azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong><br />

cortisone therapy. 3<br />

Opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections have been reported <strong>in</strong> dogs, 32, 33 but the overall prevalence <strong>of</strong> opportunistic<br />

<strong>in</strong>fections is animals on immunosuppressive doses is low.<br />

Carc<strong>in</strong>ogenesis<br />

Controversy exists as to the potential l<strong>in</strong>k between long term immunosuppressive therapy with<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> malignancy. While some authors suggest that there is currently no<br />

evidence that thiopur<strong>in</strong>e therapy is associated with an <strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>of</strong> malignancy, 13 other studies <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

that dermatology patients on long-term azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e therapy may be at risk <strong>of</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g aggressive<br />

squamous cell carc<strong>in</strong>oma, particular where the patient has had excessive exposure to UV light. 34 F<strong>in</strong>ally, yet<br />

further studies have <strong>in</strong>dicated that while an <strong>in</strong>crease risk <strong>of</strong> squamous cell carc<strong>in</strong>oma is present <strong>in</strong> renal<br />

transplant patients, it appears to be <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>of</strong> the drug <strong>use</strong>d. 35 In this study, either long term<br />

cyclospor<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e with or without corticosteroids showed no difference s<strong>in</strong> cancer risk between<br />

the groups.<br />

The method by which carc<strong>in</strong>ogenesis is proposed to occur (if at all) is due to the <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong> 6-<br />

TGN metabolites <strong>in</strong>to DNA. Once this process occurs, the DNA becomes prone to oxidation due to the high<br />

reactivity <strong>of</strong> the thiobase. Exposure to UVA light destabilises the double helix <strong>and</strong> sensitises the cell to the<br />

mutagenic effect <strong>of</strong> UV light, which is believed to be one <strong>of</strong> the ca<strong>use</strong>s <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e-related malignancies,<br />

<strong>in</strong> particular squamous cell carc<strong>in</strong>oma. 4 Additionally, azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e ca<strong>use</strong>s <strong>in</strong>activation <strong>of</strong> the mismatch repair<br />

system <strong>in</strong> myeloid precursor cells which can lead to development <strong>of</strong> drug-resistant cells. 4<br />

Hypersensitivity re<strong>action</strong>s<br />

Rare reports exist <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e hypersensitivity syndrome <strong>in</strong> humans. 36 Cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs may<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude hypotension, shock, urticarial or vasculitic eruption, fever <strong>and</strong> rhabdomyolysis. To the authors<br />

knowledge, similar re<strong>action</strong>s have not been reported <strong>in</strong> the veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature.<br />

Miscellaneous<br />

When adm<strong>in</strong>istered with isotret<strong>in</strong>o<strong>in</strong>, azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e has been reported to <strong>in</strong>duce curl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the hair <strong>in</strong><br />

humans. 3<br />

Contra<strong>in</strong>dications <strong>and</strong> drug <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>action</strong>s<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> should not be <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug. In addition<br />

dosage adjustments may need to be made <strong>in</strong> cases <strong>of</strong> renal or hepatic <strong>in</strong>sufficiency. As the safety marg<strong>in</strong> for<br />

<strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> cats is extremely low, it is not recommended for <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> this species. Use <strong>in</strong> pregnant animals should be<br />

with care as azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e is both mutagenic <strong>and</strong> teratogenic <strong>in</strong> lab animals, though no clear-cut relationship<br />

between the drug <strong>and</strong> sporadic reports <strong>of</strong> human congenital anomalies has been accepted. 1 Use should only<br />

be considered where the benefits clearly outweigh the risk <strong>and</strong> clients should be adequately counselled.<br />

There is no evidence that azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e produces gonadotoxicity or <strong>in</strong>fertility <strong>in</strong> humans. 3<br />

Xanth<strong>in</strong>e oxidase <strong>in</strong>hibitors such as allopur<strong>in</strong>ol, should not be <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e where possible. Allopur<strong>in</strong>ol <strong>in</strong>hibits the metabolism <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e to <strong>in</strong>active metabolites,<br />

thereby <strong>in</strong>crease the amount <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e available for metabolism to 6-TGNs. If allopur<strong>in</strong>ol must be <strong>use</strong>d,<br />

the dose <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e should be reduced by at least 2/3rds, however the risk <strong>of</strong> myelotoxicity rema<strong>in</strong>s. 1<br />

Angiotens<strong>in</strong>-convert<strong>in</strong>g enzyme <strong>in</strong>hibitors (ACEIs) have been shown to potentiate the effects <strong>of</strong><br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> humans. Additionally, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is an antimetabolite that has a<br />

synergistic effect <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>hibit<strong>in</strong>g bone marrow proliferation. However, the cl<strong>in</strong>ical significance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>action</strong> <strong>of</strong> these drugs with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e has not been seen <strong>in</strong> the non-renal transplant sett<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Sulfasalaz<strong>in</strong>e is an <strong>in</strong>hibitor <strong>of</strong> TPMT activity <strong>and</strong> may potentiate azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e toxicity. 3 Current therapeutic<br />

guidel<strong>in</strong>es advise aga<strong>in</strong>st concurrent <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> these medications with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e where possible.<br />

Warfar<strong>in</strong> resistance has been reported <strong>in</strong> the humans, however azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e toxicity is not enhanced<br />

by warfar<strong>in</strong>, rather the effects <strong>of</strong> warfar<strong>in</strong> are reduced. While this is a notable drug <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>action</strong> <strong>in</strong> the human<br />

50

literature, warfar<strong>in</strong> is rarely <strong>use</strong>d therapeutically <strong>in</strong> animals <strong>and</strong> may be less <strong>of</strong> a concern <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

medic<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Dosage <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> (Imuran®, GlaxoSmithKl<strong>in</strong>e) is available <strong>in</strong> 25mg <strong>and</strong> 50mg tablets <strong>and</strong> as a sodium<br />

salt for <strong>in</strong>jection (50mg vial). The recommended dose for azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> dermatology <strong>in</strong> humans <strong>and</strong> dogs is<br />

reported to be 1-2.2 mg/kg orally daily, reduc<strong>in</strong>g to every other day adm<strong>in</strong>istration after 1-2 weeks <strong>of</strong> daily<br />

therapy. However, many cl<strong>in</strong>icians advocate the <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> a body surface area derived dose rate (50mg/m 2 ) <strong>in</strong><br />

animals over 20kg.<br />

In humans, a new dos<strong>in</strong>g system (Table 3) has been proposed base on pretreatment TPMT activity.<br />

While TPMT is a <strong>use</strong>ful <strong>in</strong>dicator <strong>of</strong> potential risk groups for adverse haematologic effects, the role <strong>of</strong> TPMT<br />

activity <strong>in</strong> dogs, cats <strong>and</strong> horses rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear so dos<strong>in</strong>g based on TPMT activity <strong>in</strong> these species is not<br />

recommended.<br />

Table 3. Proposed new dos<strong>in</strong>g schedule (human) – adapted from Patel, et al. 1<br />

Patient group TPMT activity (U/ml rbcs) Suggested max. dose (mg/kg)<br />

No activity (homozygous<br />

mutation)<br />

< 5 Recommend not us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Low activity (heterozygous) 5-13.7 1<br />

Normal activity (homozygous<br />

wild type)<br />

13.8-19.5 2.5<br />

High activity (high homozygous) > 19.5 3<br />

Therapeutic response to azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e occurs <strong>in</strong> 6-8 weeks. If a response is not seen, then the<br />

azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e dose may be <strong>in</strong>creased by 0.5 mg/kg at 4 week <strong>in</strong>tervals with reference to white cell counts <strong>and</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical response, but a total dose <strong>of</strong> 3mg/kg should not be exceeded. 3 If there is no response to treatment<br />

after 12-16 weeks, azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e should be discont<strong>in</strong>ued.<br />

No formal guidel<strong>in</strong>es exist for hematological or biochemical monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><br />

dermatology patients <strong>in</strong> the human or veter<strong>in</strong>ary fields. Basel<strong>in</strong>e complete blood count (CBC) <strong>and</strong> serum<br />

biochemistry panels should be run prior to the <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> therapy. The author then repeats the CBC at<br />

weekly <strong>in</strong>tervals for the first 4 weeks <strong>of</strong> therapy, then fortnightly to 8 weeks <strong>of</strong> therapy, monthly to 16 weeks<br />

then every 3 months thereafter. Biochemical analysis (with particular reference to liver function test<strong>in</strong>g) is<br />

repeated 2 weeks after <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> therapy, <strong>and</strong> then if any evidence <strong>of</strong> gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al upset, <strong>in</strong>appetence,<br />

fever, malaise or icterus is present. Ideally, ur<strong>in</strong>e culture <strong>and</strong> sensitivity should be performed prior to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> therapy <strong>and</strong> then every 3 months, due to long term immunosuppression <strong>and</strong> the risk <strong>of</strong> occult<br />

ur<strong>in</strong>ary tract <strong>in</strong>fections (note that this risk is not specific to azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e).<br />

Chlorambucil<br />

History<br />

Chlorambucil is a potent alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agent <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> neoplastic <strong>and</strong> non-neoplastic<br />

dermatological conditions. The development <strong>of</strong> the alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>chlorambucil</strong>, have<br />

revolutionised cancer chemotherapy. Alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents are derivatives <strong>of</strong> mustard gas (nitrogen mustards),<br />

which were extensively <strong>use</strong>d as chemical warfare agents <strong>in</strong> both World War I <strong>and</strong> II. Top secret studies<br />

carried out <strong>in</strong> the early to mid 1940s revealed that when these agents were adm<strong>in</strong>istered systemically they<br />

were highly cytotoxic, with the degree <strong>of</strong> cytotoxicity positively correlated with the proliferative capacity <strong>of</strong><br />

the cells – thus nitrogen mustards <strong>and</strong> their derivatives preferentially killed highly proliferative organs such<br />

as the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract, bone marrow <strong>and</strong> lymphoid tissues. 37<br />

The first cl<strong>in</strong>ical report <strong>of</strong> nitrogen mustards us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> cancer chemotherapy was published by<br />

Goodman et. al <strong>in</strong> 1946, 38 when 67 patients with Hodgk<strong>in</strong>’s lymphoma, leukaemia <strong>and</strong> lymphosarcoma were<br />

treated with a nitrogen mustard derivative. Significant improvement was seen <strong>in</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> patients, but the<br />

marg<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> safety <strong>of</strong> the drug <strong>in</strong> these <strong>in</strong>dividuals was narrow.<br />

Chlorambucil was developed <strong>in</strong> 1953 by Everett et. al, 39 with the addition <strong>of</strong> an aryl group to the<br />

nitrogen mustard molecule known as bis-(2-chloroethyl)am<strong>in</strong>e, Addition <strong>of</strong> other active moieties onto this<br />

base molecule led to the development <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> more targeted drugs such as melphalan <strong>and</strong><br />

cyclosphosphamide. 40<br />

Pharmacology <strong>and</strong> <strong>mechanism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>action</strong><br />

Alkylation agents exert their effect directly on DNA, RNA <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>s, usually by non specific<br />

means. The chlor<strong>in</strong>e groups on the nitrogen mustard facilitate nucleophilic attack <strong>of</strong> nitrogen to form an<br />

imm<strong>in</strong>ium ion (R3N). This highly reactive ion undergoes alkylation at N7 <strong>of</strong> guan<strong>in</strong>e to form a<br />

51

monoalkylated product on the DNA str<strong>and</strong>. Repetition <strong>of</strong> this cycle ca<strong>use</strong>s cross-l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> DNA. In the case<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong>, two complementary str<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> DNA are cross-l<strong>in</strong>ked. 41 Cross-l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> DNA prevents<br />

separation <strong>of</strong> DNA str<strong>and</strong>s for transcription <strong>and</strong> subsequent failure <strong>of</strong> transcription leads to apoptosis.<br />

Chlorambucil can also covalently bond to RNA <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>s through a similar <strong>mechanism</strong>. 42<br />

Figure 4. Chemical composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong><br />

Chlorambucil is considered cell cycle non-specific. Follow<strong>in</strong>g oral adm<strong>in</strong>istration, <strong>chlorambucil</strong> is<br />

rapidly <strong>and</strong> nearly completely absorbed from the gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract. It is highly prote<strong>in</strong> bound <strong>in</strong> plasma.<br />

The major route <strong>of</strong> metabolism is spontaneous hydrolysis, though <strong>chlorambucil</strong> is also metabolized <strong>in</strong> the<br />

liver to form phenylacetic acid mustard (active compound). Phenylacetic acid mustard is further metabolized<br />

to <strong>in</strong>active products which are excreted <strong>in</strong> the ur<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> faeces. 43<br />

Indications <strong>in</strong> Dermatology<br />

Human<br />

Table 1. Selected dermatologic diseases where <strong>chlorambucil</strong> has shown to be <strong>of</strong> benefit<br />

Neoplastic disease Pyoderma gangrenosum 44<br />

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma 45, 46 Behçet’s disease<br />

Sézary syndrome 46 Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma 49<br />

Cutaneous B cell lymphoma 50 Cutaneous sarcoidosis 51<br />

Non-neoplastic disease Sweet’s syndrome 52<br />

Pemphigus vulgaris 53 Bullous pemphigoid 54<br />

Pemphigus foliaceous 53 Dermatomyositis 55<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Table 2. Selected dermatologic diseases where <strong>chlorambucil</strong> may be <strong>of</strong> benefit<br />

Mast cell tumour 56, 57 Discoid lupus erythematosus 22<br />

Fel<strong>in</strong>e eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic granuloma complex 58 Systemic lupus erythematosus 22<br />

Pemphigus foliaceous 21, 22 Immune-mediated vasculitis 22<br />

Pemphigus vulgaris 21, 22 Cold agglut<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> disease 22<br />

Superficial pemphigus complex 21, 22 Urticaria pigmentosa 56<br />

Bullous pemphigoid 22 ? Cutaneous T cell lymphoma 59<br />

Adverse effects<br />

Haematologic<br />

Bone marrow toxicity is the most common side effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong> therapy. It may be mild <strong>and</strong><br />

transient, or severe <strong>and</strong> progressive. Myelosuppression is manifested by anaemia, leukopenia <strong>and</strong><br />

thrombocytopenia. Leukocyte nadir may take 7-14 days, with recovery from 7-28 days. Severe pancytopenia<br />

may take months to years to achieve full recovery. 43<br />

Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

Na<strong>use</strong>a <strong>and</strong> vomit<strong>in</strong>g are frequent side effects <strong>of</strong> alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agent adm<strong>in</strong>istration, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong>. Na<strong>use</strong>a has been reported with<strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>utes <strong>of</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> the drug <strong>in</strong> humans, but may<br />

takes hours or days to become cl<strong>in</strong>ically apparent. 42 In general, traditional antiemetics are poorly effective <strong>in</strong><br />

controll<strong>in</strong>g vomit<strong>in</strong>g with these agents. Intractable na<strong>use</strong>a <strong>and</strong>/or vomit<strong>in</strong>g may require hospitalization <strong>and</strong><br />

symptomatic therapy. A dose reduction should be considered <strong>in</strong> severe cases.<br />

Hepatotoxicity has been documented <strong>in</strong> humans <strong>and</strong> animals with alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents, 42, 43, 60 however<br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong> has a higher safety marg<strong>in</strong> than other alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents (e.g. lomust<strong>in</strong>e) thus fatal hepatoxicity<br />

with this drug is rarely reported <strong>in</strong> the human literature <strong>and</strong>, to the authors’ knowledge, has not been reported<br />

<strong>in</strong> the veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature.<br />

47, 48<br />

52

Carc<strong>in</strong>ogenesis<br />

Due to their mutagenic properties, patients receiv<strong>in</strong>g alkylation therapy have been shown to have an<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased risk <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g a second malignancy. Acute leukaemia is most frequently described as a second<br />

malignancy <strong>in</strong> humans, <strong>and</strong> usually develops with<strong>in</strong> 1-4 years after drug exposure. 42 The phenomenon has<br />

not yet been documented <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature, possible due to the short treatment lengths <strong>in</strong> these species.<br />

Hypersensitivity re<strong>action</strong>s<br />

Anaphylaxis, urticaria <strong>and</strong> drug eruptions have been reported with <strong>chlorambucil</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> humans.<br />

Re<strong>action</strong>s to topically applies alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents may also sensitise to systemically adm<strong>in</strong>istered compounds. 42<br />

Miscellaneous<br />

Interstitial pneumonitis <strong>and</strong> pulmonary fibrosis have been reported <strong>in</strong> the human literature but not<br />

identified <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, a cumulative effect seems to be required as pulmonary<br />

fibrosis secondary to <strong>chlorambucil</strong> therapy has been noted after the discont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> therapy.<br />

Alkylat<strong>in</strong>g agents have a significant toxic effect on reproductive tissue lead<strong>in</strong>g to ovarian atrophy<br />

<strong>and</strong> aspermia. 42 As <strong>chlorambucil</strong> damages DNA at a fundamental level, it is also considered teratogenic.<br />

Alopecia a delayed regrowth <strong>of</strong> the hair coat has been reported <strong>in</strong> dogs, with Poodles <strong>and</strong> Kerry<br />

Blue Terrier more likely to be affected than other breeds. 22 As with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, the theoretical risk <strong>of</strong><br />

opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections may be <strong>in</strong>creased with long term immunosuppression, but little data exists <strong>in</strong> the<br />

human or veter<strong>in</strong>ary literature on the prevalence <strong>of</strong> opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fections associated with <strong>chlorambucil</strong> <strong>use</strong>.<br />

Contra<strong>in</strong>dications <strong>and</strong> drug <strong>in</strong>ter<strong>action</strong>s<br />

Chlorambucil should not be <strong>use</strong>d <strong>in</strong> patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug. In addition<br />

dosage adjustments may need to be made <strong>in</strong> cases <strong>of</strong> renal or hepatic <strong>in</strong>sufficiency. Use <strong>in</strong> pregnancy should<br />

be avoided unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risk.<br />

The pr<strong>in</strong>ciple concern for development <strong>of</strong> myelosuppression is concurrent <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> ant<strong>in</strong>eoplasics,<br />

immunosuppressants (e.g. azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, corticosterioids, cyclophophamide) <strong>and</strong> other bone marrow<br />

suppressive agents (e.g. chloramphenicol, flucytos<strong>in</strong>e, amphoteric<strong>in</strong> B, grise<strong>of</strong>ulv<strong>in</strong>, colchic<strong>in</strong>e). 43<br />

Dosage <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Chlorambucil (Leukeran®, GlaxoSmithKl<strong>in</strong>e) is available <strong>in</strong> a 2mg tablet. Doses range from 0.1-<br />

0.2 mg/kg (dog <strong>and</strong> cat) adm<strong>in</strong>istered orally every24-48 hours. Concurrent <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> corticosteroids may be<br />

required <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>duction phase, once cl<strong>in</strong>ical response is seen then ma<strong>in</strong>tenance on every other day dos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong> has been reported.<br />

As with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, no formal guidel<strong>in</strong>es exist for hematological or biochemical monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong> <strong>in</strong> dermatology patients <strong>in</strong> exist. Basel<strong>in</strong>e complete blood count (CBC) <strong>and</strong> serum biochemistry<br />

panels should be run prior to the <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> therapy. The author then repeats the CBC at weekly <strong>in</strong>tervals<br />

for the first 4 weeks <strong>of</strong> therapy, then fortnightly to 8 weeks <strong>of</strong> therapy, monthly to 16 weeks then every 3<br />

months thereafter. Biochemical analysis is then only repeated if there is any evidence <strong>of</strong> gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

upset, <strong>in</strong>appetence, fever, malaise or icterus present. Ideally, ur<strong>in</strong>e culture <strong>and</strong> sensitivity should be<br />

performed prior to the <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>of</strong> therapy <strong>and</strong> then every 3 months.<br />

53

References<br />

1. Patel A, Swerlick R, McCall C. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>in</strong> dermatology: the past, the present, <strong>and</strong> the future. J Am Acad<br />

Dermatol 2006;55:369-389.<br />

2. Wise M, Callen J. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong>: a guide for the management <strong>of</strong> dermatology patients. Dermatolic Therapy<br />

2007;20:206-215.<br />

3. Stern D, Tripp J, Ho V, Lebwohl M. The <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> systemic immune moderators <strong>in</strong> dermatology: an update.<br />

Dermatol Cl<strong>in</strong> 2005;23:259-300.<br />

4. Fotoohi A, Coulthard S, Albertoni F. Thiopur<strong>in</strong>es: factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g toxicity <strong>and</strong> response. Biochem Pharm<br />

2010;In Press.<br />

5. Maltzman J, Koretzky G. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong>: old drug, new <strong>action</strong>s. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest 2003;111:1122-1124.<br />

6. Gassmann A, van Furth R. The effect <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e (Imuran) on the k<strong>in</strong>etics <strong>of</strong> monocytes <strong>and</strong> macrophages<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the normal steady state <strong>and</strong> an acute <strong>in</strong>flammatory re<strong>action</strong>. Blood 1975;46:51-64.<br />

7. Levy J, Barnett E, MacDonald N, Kl<strong>in</strong>enberg J, Pearson C. The effect <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e on gammaglobul<strong>in</strong><br />

synthesis <strong>in</strong> man. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest 1972;51:2233-2238.<br />

8. Liu H, Wong C. In vitro immunosuppressive effects <strong>of</strong> methotrexate <strong>and</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e on Langerhans cells.<br />

Arch Dermatol Res 1997;289:94-97.<br />

9. Gorski A, Korczak-Kowalska G, Nowaczyk M, Paczek L, Gaciong Z. The effect <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e on term<strong>in</strong>al<br />

differentiation <strong>of</strong> human B lymphocytes. Immunopharmacology 1983;6:259-266.<br />

10. Elion G. The George Hitch<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> Gertrude Elion Lecture. The pharmacology <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e. Ann N Y Acad<br />

Sci 1993;685:400-407.<br />

11. Teide I, Fritz G, Str<strong>and</strong> S, et al. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><br />

primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest 2003;111:1133-1145.<br />

12. Ramaswamy M, Dumont C, Cruz A, et al. Cutt<strong>in</strong>g edge: Rac GTPases sensitize activated T cells to die via Fas.<br />

J Immunol 2007;179:6384-6388.<br />

13. Sahasranaman S, Howard D, Roy S. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical pharmacology <strong>and</strong> pharmacogenetics <strong>of</strong> thiopur<strong>in</strong>es. Eur J Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Pharmacol 2008;64:753-767.<br />

14. Holme S, Duley J, S<strong>and</strong>erson J, Routledge P, Anstey A. Erythrocyte thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyl transferase assessment<br />

prior to azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> the UK. QJM 2002;95:439-444.<br />

15. Salavaggione O, Kidd L, Prondz<strong>in</strong>ski J, et al. Can<strong>in</strong>e red blood cell thiopur<strong>in</strong>e S-methyltransferase: companion<br />

animal pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenetics 2002;12:713-724.<br />

16. Rodriguez D, Mack<strong>in</strong> A, Easley R, et al. Relationship between red blood cell thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyltransferase<br />

actovoty <strong>and</strong> myelotoxicity <strong>in</strong> dogs receiv<strong>in</strong>g azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:339-345.<br />

17. Kidd L, Salavaggione O, Szumlanski C, et al. Thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyltransferase activity <strong>in</strong> red blood cells <strong>of</strong> dogs.<br />

J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:214-218.<br />

18. Salavaggione O, Yang C, Kidd L, et al. Cat red blood cell thiopur<strong>in</strong>e S-methyltransferase: companion animal<br />

pharmacogenetics. J Pharmacol Exp Therap 2004;308:617-626.<br />

19. White S, Rosychuk R, Outerbridge C, et al. Thiopur<strong>in</strong>e methyltransferase <strong>in</strong> red blood cells <strong>of</strong> dogs, cats <strong>and</strong><br />

horses. J Vet Intern Med 2000;14:499-502.<br />

20. White S, Maxwell L, Szabo N, Hawk<strong>in</strong>s J, Kollias-Baker C. Pharmacok<strong>in</strong>etics <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle-dose <strong>in</strong>travenous <strong>and</strong> oral adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>and</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e follow<strong>in</strong>g chronic oral adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>in</strong><br />

horses. Am J Vet Res 2005;66:1578-1583.<br />

21. Rosenkrantz W. Pemphigus: current therapy. Vet Dermatol 2004;15:90-98.<br />

22. Scott DW, Miller WH, Griff<strong>in</strong> CE. Immune-mediated disorders. In: Scott DW, Miller WH, Griff<strong>in</strong> CE, editors.<br />

Small Animal Dermatology. 6th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2001.<br />

23. Mueller R, Rosychuk R, Jonas L. A retrospective study regard<strong>in</strong>g the treatment <strong>of</strong> lupoid onychodystrophy <strong>in</strong><br />

30 dogs <strong>and</strong> literature review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2003;39:139-150.<br />

24. Hill P, Lau P, Rybnicek J, Hargreaves J, Olivry T. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita <strong>in</strong> a Great Dane. J Small<br />

Anim Pract 2008;49:89-94.<br />

25. Jackson H. Eleven cases <strong>of</strong> vesicular cutaneous lupus erythematosus <strong>in</strong> Shetl<strong>and</strong> sheepdogs <strong>and</strong> rough collies:<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical management <strong>and</strong> prognosis. Vet Dermatol 2004;15:37-41.<br />

26. Itoh T, Nibe K, Kojimoto A, et al. Erythema multiforme possibly triggered by food substances <strong>in</strong> a dog. J Vet<br />

Med Sci 2006;68:869-871.<br />

27. Palmeiro B, Morris D, Goldschmidt M, Maudl<strong>in</strong> E. Cutaneous reactive histiocytosis <strong>in</strong> dogs: a retrospective<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> 32 cases. Vet Dermatol 2007;18:332-340.<br />

28. Favrot C, Reichmuth P, Olivry T. Treatment <strong>of</strong> can<strong>in</strong>e atopic dermatitis with azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e: a pilot study. Vet<br />

Record 2007;160:520-521.<br />

29. R<strong>in</strong>kardt N, Kruth S. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong>-<strong>in</strong>duced bone marrow toxicity <strong>in</strong> four dogs. Can Vet J 1996;37:612-613.<br />

30. Petit E, Langouet S, Akhdar H, et al. Differentoal toxic effects <strong>of</strong> azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e, 6-mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> 6thioguan<strong>in</strong>e<br />

on human hepatocytes. Toxicology <strong>in</strong> vitro 2008;22:632-642.<br />

31. Moriello K, Bowen D, Meyer D. Acute pancreatitis <strong>in</strong> two dogs given azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> prednisone. J Am Vet<br />

Med Assoc 1987 191:695-696.<br />

32. Yager J, Best S, Maggi R, et al. Bacillary angiomatosis <strong>in</strong> an immunosuppressed dog. Vet Dermatol<br />

2010;[Epub ahead <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>t].<br />

33. Gregory C, Kyles A, Bernsteen L, Mehl M. Results <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical renal transplantation <strong>in</strong> 15 dogs us<strong>in</strong>g triple drug<br />

immunosuppressive therapy. Vet Surg 2006 35:105-112.<br />

34. Bottomly W, Ford G, Cunliffe W, Cotterill J. Aggressive squamous cell carc<strong>in</strong>omas develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> patients<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g long-term azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e. Br J Dermatol 1995 133 460-462.<br />

54

35. Bouwes Bavnick J, Hardie D, Green A. The risk <strong>of</strong> sk<strong>in</strong> cancer <strong>in</strong> renal transplant recipients <strong>in</strong> Queensl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Australia. A follow-up study. Transplantation 1996;61:715-721.<br />

36. Saway P, Heck L, Bonner J, Kirl<strong>in</strong> J. <strong>Azathiopr<strong>in</strong>e</strong> hypersensitivity. Am J Med 1988 84 960-964.<br />

37. Gilman A, Phillips F. The biological <strong>action</strong>s <strong>and</strong> therapeutic applications <strong>of</strong> β-chloroethyl am<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> sulfides.<br />

Science 1946;103:409-415.<br />

38. Goodman L, W<strong>in</strong>trobe M, Dameshek W, Goodman J, Gilman A. Nitrogen mustard therapy. Use <strong>of</strong> methylbis(β-chloroethylam<strong>in</strong>e<br />

hydrochloride) <strong>and</strong> tris(β-chloroethyl)am<strong>in</strong>e hydrochloride for Hodgk<strong>in</strong>'s disease,<br />

lymphosarcoma, leukemia <strong>and</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> allied <strong>and</strong> miscellaneous disorders. JAMA 1946;132:126-132.<br />

39. Everett J, Roberts J, Ross W. Aryl-2-halogenoalkylam<strong>in</strong>es. XII: Some carboxylic derivatives <strong>of</strong> N,N-di-2chloroaethylanil<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

J Chem Soc 1953:2386-2392.<br />

40. Maxwell R, Eckhardt S. Drug discovery: a casebook <strong>and</strong> analysis. Humana Press, 1990.<br />

41. Hurley L. DNA <strong>and</strong> its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2002;2:188-<br />

200.<br />

42. Tew K. Alkylat<strong>in</strong>g Agents. In: DeVita V, Lawrence T, Rosenberg S, editors. Cancer: pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>and</strong> practice<br />

<strong>of</strong> oncology. 8th edn. Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s, Philadelphia, 2008:407-419.<br />

43. Plumb D. Plumb's Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Drug H<strong>and</strong>book. Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g, Stockholm, WI, 2005.<br />

44. Woll<strong>in</strong>a U. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical management <strong>of</strong> pyoderma gangrenosum. Am J Cl<strong>in</strong> Dermatol 2002;3:149-158.<br />

45. Sche<strong>in</strong>feld N. A brief primer on treatments <strong>of</strong> cutaneous T cell lymphoma newly approved or late <strong>in</strong><br />

development. J Drugs Dermatol 2007;6:757-760.<br />

46. Holmes R, McGibbon D, Black M. Mycosis fungoides: progression towards Sézary syndrome reversed with<br />

<strong>chlorambucil</strong>. Cl<strong>in</strong> Exp Derm 1983;8:429-435.<br />

47. Zouboulis C. Extended venous thrombosis <strong>in</strong> Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease. Eur J Dermatol 2004;14:268-<br />

271.<br />

48. Elbirt D, Asher I, Sthoeger Z. Behçet’s disease - cl<strong>in</strong>ical presentation, diagnostic <strong>and</strong> therapeutic approach.<br />

Harefuah 2002;141:462-467, 497.<br />

49. Torabian S, Fazel N, Knuttle R. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma treated with <strong>chlorambucil</strong>. Dermatol Onl<strong>in</strong>e J<br />

2006;12:11.<br />

50. Hoefnagel J, Vermeer M, Jansen P, Heule F. Primary cutaneous marg<strong>in</strong>al zone B-cell lymphoma. Arch<br />

Dermatol 2005;141:1139-1145.<br />

51. Doherty C, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs 2008;68:1361-1383.<br />

52. Case J, Smith S, Callen J. The <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> pulse methylprednisolone <strong>and</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong> <strong>in</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong> Sweet's<br />

syndrome. Cutis 1989;44:125-129.<br />

53. Shah N, Green A, Elgart G, Kerdel F. The <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong> with prednisolone <strong>in</strong> the treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:85-88.<br />

54. Milligan A, Hutch<strong>in</strong>son P. The <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>chlorambucil</strong> <strong>in</strong> the treament <strong>of</strong> bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad<br />

Dermatol 1990;22:796-801.<br />

55. S<strong>in</strong>oway P, Callen J. Chlorambucil. An effective corticosteroid-spra<strong>in</strong>g agent for patients with recalcitrant<br />

dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:319-324.<br />

56. Thamm D, Vail D. Mast cell tumours. In: Withrow S, Vail D, editors. Small Animal Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Oncology. 4th<br />

edn. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, 2007:402-424.<br />

57. Taylor F, Gear R, Hoather T, Dobson J. Chlorambucil <strong>and</strong> prednisolone chemotherapy for dogs with<br />

<strong>in</strong>operable mast cell tumours: 21 cases. J Small Anim Pract 2009;50:284-289.<br />

58. White S. Nonsteroidal immunosuppressive therapy. In: Bonagura J, editor. Kirk's Current Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Therapy:<br />

XIII Small Animal Practice. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2000:536-538.<br />

59. Guaguere E, Muller A, Degorce-Rubiales F. Epithelitropic mucocutaneous T cell lymphoma. In: Guaguere E,<br />

Prelaud P, Craig M, editors. A Practical Guide to Can<strong>in</strong>e Dermatology. Kalianxis Publish<strong>in</strong>g, Italy, 2008:493–500.<br />

60. Kristal O, Rassnick K, Gliatto J, et al. Hepatotoxicity associated with CCNU (lomust<strong>in</strong>e) chemotherapy <strong>in</strong><br />

dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:75-80.<br />

55