Inside Papua New Guinea - ExxonMobil

Inside Papua New Guinea - ExxonMobil

Inside Papua New Guinea - ExxonMobil

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

carbon-bearing reservoirs below<br />

these displaced salt features.<br />

However, the imaging technology<br />

allowing geoscientists to plan<br />

exploration wells to determine the<br />

commercial potential of subsalt<br />

prospects was still in very early<br />

development.<br />

A faint bump<br />

That didn’t stop <strong>ExxonMobil</strong><br />

seismic interpreter Flip Koch from<br />

putting pencil to paper to analyze<br />

newly acquired seismic data prior<br />

to a 1999 Gulf lease sale.<br />

Koch detected a structure<br />

beneath the subsalt that<br />

appeared as a faint “bump” on<br />

several seismic lines in an unexplored<br />

area that possibly others<br />

had not detected. As it turned<br />

out, <strong>ExxonMobil</strong> was the only<br />

7<br />

company to bid on the Keathley<br />

Canyon blocks that would eventually<br />

yield hundreds of millions of<br />

barrels of oil.<br />

Ricardo Livieres played a key<br />

role on the technical team that<br />

followed up Koch’s work to confirm<br />

that the Hadrian blocks represented<br />

a “good neighborhood”<br />

for oil and gas exploration.<br />

“We learned that a strong system<br />

was present for generating<br />

hydrocarbons, a number of reservoirs<br />

were available to explore<br />

and that the structure covered a<br />

large area,” says Livieres. “But you<br />

never know for sure until you drill.”<br />

Hadrian-1, drilled in 2004-<br />

2005 to a total depth of 27,973<br />

feet, proved dry in the deep<br />

objective. However, hydrocarbon-bearing<br />

reservoirs were<br />

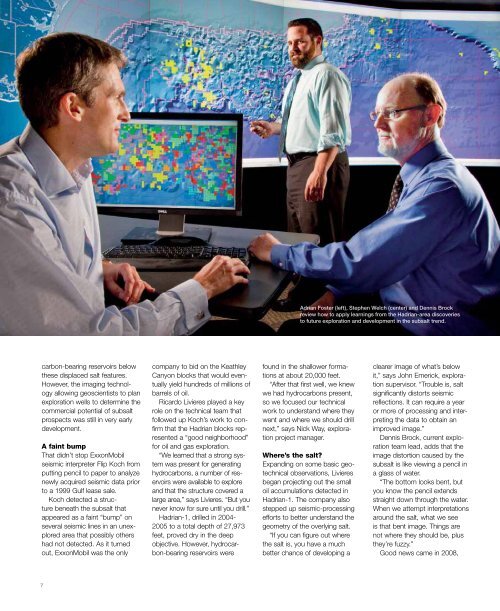

Adrian Foster (left), Stephen Welch (center) and Dennis Brock<br />

review how to apply learnings from the Hadrian-area discoveries<br />

to future exploration and development in the subsalt trend.<br />

found in the shallower formations<br />

at about 20,000 feet.<br />

“After that first well, we knew<br />

we had hydrocarbons present,<br />

so we focused our technical<br />

work to understand where they<br />

went and where we should drill<br />

next,” says Nick Way, exploration<br />

project manager.<br />

Where’s the salt?<br />

Expanding on some basic geotechnical<br />

observations, Livieres<br />

began projecting out the small<br />

oil accumulations detected in<br />

Hadrian-1. The company also<br />

stepped up seismic-processing<br />

efforts to better understand the<br />

geometry of the overlying salt.<br />

“If you can figure out where<br />

the salt is, you have a much<br />

better chance of developing a<br />

clearer image of what’s below<br />

it,” says John Emerick, exploration<br />

supervisor. “Trouble is, salt<br />

significantly distorts seismic<br />

reflections. It can require a year<br />

or more of processing and interpreting<br />

the data to obtain an<br />

improved image.”<br />

Dennis Brock, current exploration<br />

team lead, adds that the<br />

image distortion caused by the<br />

subsalt is like viewing a pencil in<br />

a glass of water.<br />

“The bottom looks bent, but<br />

you know the pencil extends<br />

straight down through the water.<br />

When we attempt interpretations<br />

around the salt, what we see<br />

is that bent image. Things are<br />

not where they should be, plus<br />

they’re fuzzy.”<br />

Good news came in 2008,