Study 3: Ecodestruction and the Right to Food: The Cases of Water ...

Study 3: Ecodestruction and the Right to Food: The Cases of Water ...

Study 3: Ecodestruction and the Right to Food: The Cases of Water ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

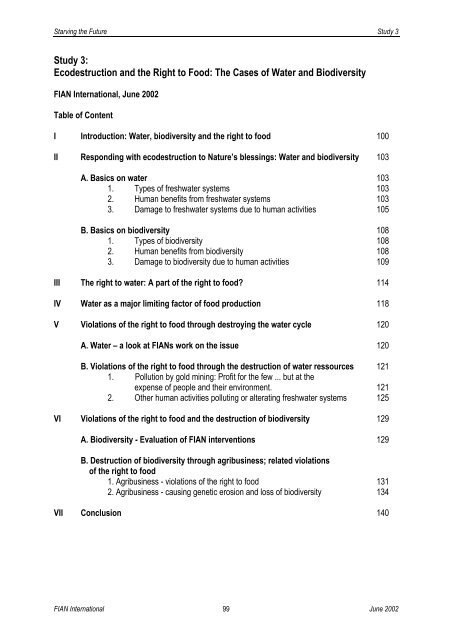

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

<strong>Study</strong> 3:<br />

<strong>Ecodestruction</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Food</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Cases</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity<br />

FIAN International, June 2002<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Content<br />

I Introduction: <strong>Water</strong>, biodiversity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food 100<br />

II Responding with ecodestruction <strong>to</strong> Nature’s blessings: <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> biodiversity 103<br />

A. Basics on water 103<br />

1. Types <strong>of</strong> freshwater systems 103<br />

2. Human benefits from freshwater systems 103<br />

3. Damage <strong>to</strong> freshwater systems due <strong>to</strong> human activities 105<br />

B. Basics on biodiversity 108<br />

1. Types <strong>of</strong> biodiversity 108<br />

2. Human benefits from biodiversity 108<br />

3. Damage <strong>to</strong> biodiversity due <strong>to</strong> human activities 109<br />

III <strong>The</strong> right <strong>to</strong> water: A part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food? 114<br />

IV <strong>Water</strong> as a major limiting fac<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> food production 118<br />

V Violations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food through destroying <strong>the</strong> water cycle 120<br />

A. <strong>Water</strong> – a look at FIANs work on <strong>the</strong> issue 120<br />

B. Violations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food through <strong>the</strong> destruction <strong>of</strong> water ressources 121<br />

1. Pollution by gold mining: Pr<strong>of</strong>it for <strong>the</strong> few ... but at <strong>the</strong><br />

expense <strong>of</strong> people <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir environment. 121<br />

2. O<strong>the</strong>r human activities polluting or alterating freshwater systems 125<br />

VI Violations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> destruction <strong>of</strong> biodiversity 129<br />

A. Biodiversity - Evaluation <strong>of</strong> FIAN interventions 129<br />

B. Destruction <strong>of</strong> biodiversity through agribusiness; related violations<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food<br />

1. Agribusiness - violations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food 131<br />

2. Agribusiness - causing genetic erosion <strong>and</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> biodiversity 134<br />

VII Conclusion 140<br />

FIAN International 99<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

I. Introduction: <strong>Water</strong>, Biodiversity, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Right</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>Food</strong><br />

<strong>Water</strong> is <strong>the</strong> cradle <strong>of</strong> life – <strong>and</strong> biodiversity is life’s unfolding symphony. It is between <strong>the</strong>se two poles<br />

that ecosystems develop, such as <strong>the</strong> soils, forests <strong>and</strong> marine systems. <strong>The</strong>ir links <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> human right<br />

<strong>to</strong> food have been investigated in earlier studies. 1 Human society <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r with its political <strong>and</strong> social<br />

institutions <strong>and</strong> its economy are but a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> larger ecosystems <strong>of</strong> Nature <strong>and</strong> subject <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> same<br />

laws <strong>and</strong> limitations.<br />

Through overconsumption <strong>and</strong> population growth <strong>the</strong> human species has recently started exhausting<br />

<strong>and</strong> polluting <strong>the</strong> cradle <strong>of</strong> life – <strong>and</strong> diminishing <strong>the</strong> voices in life’s symphony: Up<strong>to</strong> a hundred species<br />

get extinguished every day 2 – <strong>the</strong> largest rate <strong>of</strong> extinction in <strong>the</strong> his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> life on this planet. 3<br />

<strong>The</strong> dependence <strong>of</strong> human society on water is obvious. <strong>Water</strong> is crucial: a determinant <strong>of</strong> health, an<br />

ingredient <strong>to</strong> agriculture, an input for industry. Whereas <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> water as a part <strong>of</strong> food <strong>and</strong> for<br />

<strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> food are easy <strong>to</strong> grasp, <strong>the</strong> food-related importance <strong>of</strong> biodiversity might not be quite<br />

as obvious, although in a more intricate way it is equally essential for <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> food (<strong>and</strong> for<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>r human purposes) – besides having an intrinsic value in itself. Both, <strong>the</strong> water cycle <strong>and</strong><br />

biodiversity suffer man-made destruction with grave consequences for people’s access <strong>to</strong> food – now<br />

<strong>and</strong> in future. Control over water <strong>and</strong> (nowadays also) biodiversity can be a <strong>to</strong>ol for oppression. <strong>The</strong><br />

freedom <strong>and</strong> human dignity <strong>of</strong> marginalized groups – <strong>and</strong> sometimes even large sec<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

population – is at stake.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first civilizations have developped around <strong>the</strong> control <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> water: Mesopotamia<br />

(Euphrates <strong>and</strong> Tigris), Egypt (Nile), India (Indus), China (Hoangho, Yangtze). Civilizations since <strong>the</strong><br />

dawn <strong>of</strong> civilization have been beset with oppression, violence <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> exercise <strong>of</strong> brute force. Access<br />

<strong>to</strong> water has been a key issue in this context. <strong>The</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> civilization, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, also<br />

embodies an attempt <strong>to</strong> confine <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> force <strong>and</strong> put a check on oppression within a concept <strong>of</strong><br />

social justice <strong>and</strong> – in modern times - have it based on transparent mechanisms <strong>and</strong> legal procedures:<br />

<strong>The</strong> rule <strong>of</strong> law, based nationally <strong>and</strong> internationally on human rights.<br />

<strong>The</strong> human right <strong>to</strong> food – just as o<strong>the</strong>r human rights as well - is meant as a mechanism for deprived or<br />

threatened persons or groups <strong>to</strong> secure a certain basic st<strong>and</strong>ard in society without being dependent on<br />

<strong>the</strong> benevolence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rich <strong>and</strong> powerful who control <strong>the</strong> bulk <strong>of</strong> resources. Human rights are <strong>to</strong> be<br />

realized with certainty through courts or similar procedures - even against <strong>the</strong> interests <strong>of</strong> ruling elites.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> past decades human rights have become increasingly important terms <strong>of</strong> reference: Economic<br />

<strong>and</strong> social human rights categories were applied <strong>to</strong> a growing number <strong>of</strong> contexts without giving up <strong>the</strong><br />

essential unity across <strong>the</strong> different classes <strong>of</strong> economic, social, cultural, civil <strong>and</strong> political human rights.<br />

Three key elements <strong>of</strong> human rights are <strong>to</strong> be distinguished: Certain basic st<strong>and</strong>ards in <strong>the</strong> different<br />

realms <strong>of</strong> life in society <strong>to</strong> which everybody in society has a legitimate claim. Secondly <strong>the</strong> idea that<br />

states must not be oppressors but protect people against oppression. Thirdly <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>to</strong> introduce legal<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r mechanisms which would allow victims <strong>of</strong> oppression <strong>to</strong> have <strong>the</strong> State do its duty.<br />

<strong>The</strong> basic st<strong>and</strong>ard (or “normative content”) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate food describes a certain quality <strong>of</strong><br />

life <strong>to</strong> which everybody is entitled <strong>to</strong> under this right. <strong>The</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> this basic st<strong>and</strong>ard would be<br />

conceived as deprivation – <strong>and</strong> pushing people in<strong>to</strong> deprivation <strong>and</strong>/or keeping <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong>re is seen as<br />

oppression.<br />

FIAN International 100<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

<strong>The</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate food as a human right entitles each <strong>and</strong> every human being <strong>to</strong> access <strong>to</strong><br />

adequate food. When, however, is food adequate? And what kind <strong>of</strong> access is meant? <strong>The</strong> most<br />

authoritative interpretation so far <strong>of</strong> international right <strong>to</strong> food law (<strong>the</strong> 1999 General Comment 12 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

UN CESCR) sees <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate food as much more than <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> hunger <strong>and</strong><br />

malnutrition: According <strong>to</strong> GC 12 <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate food is fully realised when "every man, woman<br />

<strong>and</strong> child, alone or in community with o<strong>the</strong>rs, has physical <strong>and</strong> economic access at all times <strong>to</strong> adequate<br />

food or means for its procurement" <strong>and</strong> (as may be added for <strong>the</strong> sake <strong>of</strong> completeness), if this access<br />

is safeguarded by justiciable provisions providing remedy <strong>and</strong> satisfaction. In particular: "<strong>The</strong> right <strong>to</strong><br />

food shall <strong>the</strong>refore not be interpreted in a narrow or restrictive sense which equates it with a minimum<br />

package <strong>of</strong> calories, proteins <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r specific nutrients." Adequate food must be "sufficient <strong>to</strong> satisfy<br />

<strong>the</strong> dietary needs <strong>of</strong> individuals, free from adverse substances, <strong>and</strong> acceptable within a given culture<br />

(para 8)". Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se three aspects is fur<strong>the</strong>r detailed in paras 9, 10 <strong>and</strong> 11 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Comment:<br />

Dietary needs require a mix <strong>of</strong> nutrients for "physical <strong>and</strong> mental growth, development <strong>and</strong><br />

maintenance" depending on <strong>the</strong> respective occupation, gender, or age. "Measures may <strong>the</strong>refore need<br />

<strong>to</strong> be taken <strong>to</strong> maintain, adapt or streng<strong>the</strong>n dietary diversity <strong>and</strong> appropriate consumption <strong>and</strong> feeding<br />

patterns, including breast feeding, while ensuring that changes in availability <strong>and</strong> access <strong>to</strong> food supply<br />

as a minimum do not negatively affect dietary composition <strong>and</strong> intake."<br />

<strong>Food</strong> must be free from adverse substances. Adverse substances include those that originate through<br />

contamination or adulteration in <strong>the</strong> food chain, but also naturally occuring <strong>to</strong>xins.<br />

Cultural acceptability refers <strong>to</strong> non-nutrient based values attached <strong>to</strong> food <strong>and</strong> food consumption <strong>and</strong><br />

informed consumer concerns regarding <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> accessible food supplies.<br />

"Accessibility encompasses both economic <strong>and</strong> physical accessibility: ..." (para 13). <strong>Food</strong> is<br />

economically accessible for a person or community if <strong>the</strong> person or community has access <strong>to</strong> food as a<br />

result <strong>of</strong> its economic activities in <strong>the</strong> widest sense. <strong>The</strong>se economic activities can be direct food<br />

production based on access <strong>to</strong> natural productive resources (l<strong>and</strong>, water, forest, pastures, fishing<br />

grounds) <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r resources <strong>and</strong> means <strong>of</strong> production. It can also mean work as a selfemployed or<br />

wage-employed person.<br />

Para 12 specifies for <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> food: Availability refers <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> possibilities ei<strong>the</strong>r for feeding<br />

oneself directly from productive l<strong>and</strong> or o<strong>the</strong>r natural resources, or for well-functioning distribution,<br />

processing <strong>and</strong> market systems that can move food from <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> production <strong>to</strong> where it is needed<br />

...Moreover economic accessibility applies <strong>to</strong> any acquisition pattern or entitlement through which<br />

people procure <strong>the</strong>ir food <strong>and</strong> is a measure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>to</strong> which it is satisfac<strong>to</strong>ry for <strong>the</strong> enjoyment <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate food.(para 13) <strong>The</strong> income generated by such acquisition patterns <strong>and</strong><br />

entitlements is <strong>to</strong> be sufficent for an adequate st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> living including food <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r basic needs as<br />

well: Economic accessibility implies that personal <strong>and</strong> household financial cost associated with <strong>the</strong><br />

acquisition <strong>of</strong> food for an adequate diet should be at a level that <strong>the</strong> attainment <strong>and</strong> satisfaction <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

basic needs are not threatened or compromised.(para 13). Without means for <strong>the</strong> procurement <strong>of</strong> food,<br />

economic access <strong>to</strong> food is impossible. <strong>The</strong> normative content containing both economic <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

access <strong>to</strong> food implies <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> entitlement <strong>to</strong> access <strong>the</strong> means for its procurement: Natural<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r resources (skills, knowledge, markets etc.).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Comment (in para 8) puts particular emphasis on "<strong>The</strong> accessibility <strong>of</strong> such food in ways that are<br />

sustainable …” This can be seen as an ecological as well as an economic requirement. “<strong>The</strong> notion <strong>of</strong><br />

sustainability is intrinsically linked <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> adequate food or food security, implying food being<br />

accessible for both present <strong>and</strong> future generations <strong>and</strong> ... sustainability incorporates <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> longterm<br />

availability <strong>and</strong> accessibility” (GC 12, para 7). Whereas long-term availability points <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ecological limitations <strong>of</strong> food production <strong>and</strong> distribution, long-term accessibility (<strong>of</strong> available food) points<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> need that <strong>the</strong> access <strong>to</strong> food itself must not be risky but reliable over time - even over a long<br />

period <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

FIAN International 101<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

Human rights are a source <strong>of</strong> states obligations. This is true for <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food as for any o<strong>the</strong>r human<br />

right. <strong>The</strong> International Covenant on Economic, Social <strong>and</strong> Cultural <strong>Right</strong>s recognizes some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

obligations as legal obligations under international law.<br />

<strong>The</strong> general legal obligation appears in article 2 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> International Covenant on Economic, Social <strong>and</strong><br />

Cultural <strong>Right</strong>s: "Each State Party <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> present Covenant undertakes <strong>to</strong> take steps, individually <strong>and</strong><br />

through international assistance <strong>and</strong> co-operation, especially economic <strong>and</strong> technical, <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> maximum<br />

<strong>of</strong> its available resources, with a view <strong>to</strong> achieving progressively <strong>the</strong> full realization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights<br />

recognized in <strong>the</strong> present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly <strong>the</strong> adoption <strong>of</strong><br />

legislative measures. "<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are three types <strong>of</strong> states obligations linked <strong>to</strong> each human right, including <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food:<br />

Obligation-<strong>to</strong>-respect (or respect-bound obligations). Obligation-<strong>to</strong>-protect (or protect-bound obligations)<br />

<strong>and</strong> obligations-<strong>to</strong>-fulfill (or fulfil-bound obligations). What is <strong>to</strong> be respected, protected <strong>and</strong> fulfilled<br />

should be clear: It is <strong>the</strong> basic st<strong>and</strong>ard (or normative content) linked <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> human right in question - its<br />

first key element.<br />

<strong>The</strong> obligation <strong>to</strong> respect existing access <strong>to</strong> adequate food requires states parties not <strong>to</strong> take any<br />

measures that result in preventing such access. <strong>The</strong> obligation <strong>to</strong> protect requires measures by <strong>the</strong><br />

State <strong>to</strong> ensure that enterprises or individuals do not deprive individuals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir access <strong>to</strong> food.<br />

Whereas <strong>the</strong> target groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> obligations <strong>to</strong> respect <strong>and</strong> protect access <strong>to</strong> food are individuals or<br />

groups who enjoy such access, <strong>the</strong> obligation <strong>to</strong> fulfil refers <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> individuals or groups<br />

deprived <strong>of</strong> such access.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fulfilment-bound obligations require that <strong>the</strong> State must take <strong>the</strong> necessary measures <strong>to</strong> guarantee<br />

deprived groups’ access <strong>to</strong> adequate food <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> food producing resources. Under <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> adequate<br />

food, access <strong>to</strong> food for deprived persons includes access <strong>to</strong> productive resources including<br />

employment - <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> sharing <strong>of</strong> resources <strong>and</strong> food in systems <strong>of</strong> social security (based on <strong>the</strong> state,<br />

community or family). General Comment 12 insists both on physical <strong>and</strong> economic access <strong>to</strong> food <strong>and</strong><br />

hence on sharing resources <strong>and</strong> income. Resource shared could be natural resources (such as l<strong>and</strong> in<br />

a l<strong>and</strong> reform, or water), capital resources, human resources (such as skills), while income sharing<br />

programmes might include minimum income programmes (minimum wage enforcement, employment<br />

programmes, basic income, social security payments), food stamps <strong>and</strong> food subsidies, or emergency<br />

food aid.<br />

Violations <strong>of</strong> a human right are breaches <strong>of</strong> states obligations, in particular breaches <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

generic obligations - or a discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry way <strong>of</strong> meeting <strong>the</strong>m. States discriminate, if <strong>the</strong>y make<br />

differences between categories <strong>of</strong> people when meeting <strong>the</strong>ir obligations.<br />

Violations are <strong>the</strong>refore always an act (or inaction) <strong>of</strong> states (including <strong>the</strong>ir national <strong>and</strong> international<br />

states’ authorities).<br />

<strong>The</strong> destruction <strong>and</strong>/or control <strong>of</strong> water <strong>and</strong> biodiversity raises <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> oppression <strong>of</strong> marginalized<br />

groups (<strong>to</strong>day <strong>and</strong> in future), <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> related states obligations. <strong>The</strong> conceptual background<br />

given in this introduction will serve as a <strong>to</strong>ol <strong>to</strong> consider <strong>the</strong>se questions. Before doing so, however, we<br />

shall take a closer look at <strong>the</strong> human benefit derived from water <strong>and</strong> biodiversity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> damaging<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> current human activities both on water <strong>and</strong> biodiversity even <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> ecodestruction.<br />

FIAN International 102<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

II. Responding with <strong>Ecodestruction</strong> <strong>to</strong> Nature’s<br />

Blessings: <strong>Water</strong> <strong>and</strong> Biodiversity<br />

A. Basics on <strong>Water</strong><br />

Looking at <strong>the</strong> Earth from outer space one could think that <strong>the</strong> water resources were so plentiful that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y could sustain all life forever. But, almost all <strong>of</strong> Earth's water is <strong>the</strong> salty water <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oceans. This<br />

water supports an incredible biodiversity <strong>of</strong> marine life, but humans <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-dwelling animals cannot<br />

drink it, <strong>and</strong> we cannot water our crops with it. Humans require fresh, clean water <strong>to</strong> drink, <strong>and</strong> can<br />

survive for only about one week without it.<br />

Only a very tiny portion <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> Earth's water is fresh water, <strong>and</strong> an even smaller amount <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fresh<br />

water is available <strong>to</strong> us. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fresh water is locked up in frozen glaciers, in humidity, or fossil<br />

water way deep in <strong>the</strong> Earth. Rivers, lakes <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s represent only 0.01% <strong>of</strong> freshwater supplies<br />

<strong>and</strong> 1% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> our planet. 4 Although desalination provides <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> producing fresh<br />

water from <strong>the</strong> seas, <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> energy required in this process for <strong>the</strong> production <strong>and</strong> distribution<br />

prevent this technology from <strong>of</strong>fering a large scale solution <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> growing scarcity <strong>of</strong> fresh water.<br />

1. Types <strong>of</strong> freshwater systems<br />

Freshwater systems include rivers, lakes <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s. In addition <strong>to</strong> this surface water, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

ground water sources. Those sources can be classified in<strong>to</strong> two different categories: <strong>Water</strong> that is<br />

independent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> normal run<strong>of</strong>f cycle (a minor proportion) <strong>and</strong> water that comes from shallower<br />

aquifers fed by <strong>the</strong> normal run<strong>of</strong>f (which also feeds rivers <strong>and</strong> lake). <strong>The</strong>re is <strong>the</strong>refore an intimate link<br />

between ground <strong>and</strong> surface water sources. In fact, it is <strong>of</strong>ten difficult <strong>to</strong> separate <strong>the</strong> two because <strong>the</strong>y<br />

"feed" each o<strong>the</strong>r. In order <strong>to</strong> better underst<strong>and</strong> this fundamental interdependence, we can describe <strong>the</strong><br />

hydrologic cycle:<br />

As rain or snow falls <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> earth's surface some water runs <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> rivers, lakes, streams <strong>and</strong><br />

oceans (surface water). <strong>Water</strong> also can move in<strong>to</strong> those bodies by percolation below ground. <strong>Water</strong><br />

entering <strong>the</strong> soil can infiltrate deeper <strong>to</strong> reach groundwater which can discharge <strong>to</strong> surface water or<br />

return <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface through wells, springs <strong>and</strong> marshes. Here it becomes surface water again. And,<br />

upon evaporation, it completes <strong>the</strong> cycle. This movement <strong>of</strong> water between <strong>the</strong> earth <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

atmosphere through evaporation, precipitation, infiltration <strong>and</strong> run<strong>of</strong>f is continuous.<br />

i. Rivers/Streams <strong>and</strong> Lakes<br />

Streams <strong>and</strong> rivers take part in <strong>the</strong> physical <strong>and</strong> chemical cycles that shape our planet <strong>and</strong> allow life <strong>to</strong><br />

exist. <strong>The</strong>y provide different habitats for plants <strong>and</strong> animals, <strong>and</strong> are a source <strong>of</strong> food for animals, plants<br />

<strong>and</strong> human communities. Rivers <strong>and</strong> lakes are nurseries for salmon <strong>and</strong> for many insects. Rivers carry<br />

glacial silt <strong>and</strong> sediments down from <strong>the</strong> mountains, creating rich agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s by depositing it<br />

downstream on its floodplain <strong>and</strong> fertilizing <strong>the</strong> ocean, allowing marine organisms <strong>to</strong> thrive near <strong>the</strong><br />

river's mouth. Even a small mountain stream provides an as<strong>to</strong>nishing number <strong>of</strong> different habitats for<br />

plants <strong>and</strong> animals.<br />

ii. Wetl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Wetl<strong>and</strong>s is <strong>the</strong> collective term for marshes, swamps, bogs <strong>and</strong> similar areas. It also includes<br />

floodplains <strong>and</strong> flooded forests. Wetl<strong>and</strong>s are found in flat vegetated areas, in depressions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> between water <strong>and</strong> dry l<strong>and</strong> along <strong>the</strong> edges <strong>of</strong> streams, rivers, lakes <strong>and</strong> coastlines.<br />

Wetl<strong>and</strong> areas can be found in nearly every country <strong>and</strong> climatic zone. Inl<strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s receive water<br />

from precipitation, ground water <strong>and</strong>/or surface water.<br />

FIAN International 103<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

iii. Groundwater<br />

Groundwater is <strong>the</strong> water that saturates <strong>the</strong> tiny spaces between alluvial material (s<strong>and</strong>, gravel, silt,<br />

clay) or <strong>the</strong> crevices or fractures in rocks. Most groundwater is found in aquifers-underground layers <strong>of</strong><br />

porous rock that are saturated from above or from structures sloping <strong>to</strong>ward it. Groundwater is a highly<br />

vulnerable resource. Its purity <strong>and</strong> availability were used <strong>to</strong> be taken for granted. Now pollution <strong>and</strong><br />

overuse are seriously affecting <strong>the</strong> supplies: Excessive pumping <strong>of</strong> groundwater has dramatically<br />

lowered groundwater tables in many areas – in Bangkok for example by 25 meters since 1950. 5<br />

2. Human benefits from freshwater systems<br />

In <strong>the</strong> continuous natural cycle <strong>of</strong> water, different ecosystems perform irreplaceable functions, secure a<br />

stable water balance in terrestrial areas <strong>and</strong> thus enable <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> water by human beings. Only a<br />

sustainable use that has been adjusted <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>se natural cycles can maintain <strong>the</strong> productive interplay<br />

between water <strong>and</strong> nature on a lasting basis. It is only within <strong>the</strong> confines <strong>of</strong> this natural cycle that water<br />

can be regarded as a “renewable resource”.<br />

Agenda 21 states "<strong>Water</strong> is needed in all aspects <strong>of</strong> life. <strong>The</strong> general objective is <strong>to</strong> make certain that<br />

adequate supplies <strong>of</strong> water <strong>of</strong> good quality are maintained for <strong>the</strong> entire population <strong>of</strong> this planet, while<br />

preserving <strong>the</strong> hydrological, biological <strong>and</strong> chemical functions <strong>of</strong> ecosystems, adapting human activities<br />

within <strong>the</strong> capacity limits <strong>of</strong> nature <strong>and</strong> combating vec<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> water-related diseases. <strong>The</strong> multisec<strong>to</strong>ral<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> water resources development in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> socio-economic development must be<br />

recognized, as well as <strong>the</strong> multi-interest utilization <strong>of</strong> water resources for water supply <strong>and</strong> sanitation,<br />

agriculture, industry, urban development, hydropower generation, inl<strong>and</strong> fisheries, transportation,<br />

recreation, low <strong>and</strong> flat l<strong>and</strong>s management <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r activities" .<br />

i. <strong>Water</strong> supply: vital element for food<br />

<strong>The</strong> most essential food services delivered by freshwater systems is <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> water supply. On<br />

<strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, water is vital <strong>to</strong> human beings as drinking water. As such it is part <strong>of</strong> food. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

h<strong>and</strong>, water is essential for washing <strong>and</strong> cooking <strong>the</strong> food items that have <strong>to</strong> be processed. Moreover,<br />

water has become a key element <strong>of</strong> agriculture. <strong>Food</strong> production would not have reached <strong>the</strong> levels it<br />

has achieved without significant progress in irrigating agricultural l<strong>and</strong>. <strong>The</strong> agrarian sec<strong>to</strong>r highly<br />

depends on freshwater availability <strong>and</strong> quality. With <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> industrialized agriculture, water<br />

consumption for irrigation purposes has drastically increased. <strong>Water</strong> has become <strong>the</strong> major limiting<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>r in food production as will be detailed in chapter IV.<br />

ii. Freshwater habitats as a source <strong>of</strong> protein<br />

Freshwater systems provide habitats for fish <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r aquatic species, which are food resources for<br />

billions <strong>of</strong> people. Indeed, in many countries <strong>and</strong> regions, fish capture from freshwater systems is one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> main sources <strong>of</strong> protein. This especially concerns <strong>the</strong> most deprived groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population. For<br />

instance, <strong>the</strong> FAO reports that inl<strong>and</strong> fisheries yield three-quarters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> animal protein for poor families<br />

in Malawi. In Zambia, fish is also <strong>the</strong> first source <strong>of</strong> animal protein, <strong>and</strong> plays a fundamental role in <strong>the</strong><br />

nutrition <strong>of</strong> lower-income groups. Finally, <strong>the</strong> FAO observes that fish represents <strong>the</strong> single most<br />

important source <strong>of</strong> animal protein for <strong>the</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>an population. 6<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> human food, fish is also used for animal feed, which in turn provides humans with animal<br />

proteins.<br />

iii. O<strong>the</strong>r vital services for human life<br />

Freshwater systems have regenerative capacities as ecological sinks for human wastes. Thanks <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

oxygen it contains, moving surface water (<strong>and</strong> especially rivers) has <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>to</strong> dilute, process <strong>and</strong><br />

clean dumped wastes.<br />

Freshwater is a key element <strong>of</strong> human economic <strong>and</strong> industrial activity: Most industrial processes use<br />

water as an input. Rivers are important for <strong>the</strong> transportation <strong>of</strong> raw materials <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r goods. Finally,<br />

FIAN International 104<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

water is a renewable source <strong>of</strong> energy <strong>and</strong> already plays a key role throughout <strong>the</strong> world providing<br />

hydroelectricity. Due <strong>to</strong> huge dams projects, Asia <strong>and</strong> in particular China rely increasingly on<br />

waterpower. In China, <strong>the</strong> share <strong>of</strong> renewable energy (mostly hydro) amounts <strong>to</strong> 20% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal<br />

national energy production. This share amounts <strong>to</strong> 28% in South America: In countries like Brazil<br />

hydroelectricity plays a major role. 7<br />

Last but not least, human beings need water for curative (<strong>the</strong>rmal cures, etc…) <strong>and</strong> recreational<br />

purposes (water sports <strong>and</strong> hobbies such as fishing).<br />

iv. Essential services for <strong>the</strong> balance <strong>of</strong> ecosystems<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> water for domestic use, freshwater ecosystems fulfil many o<strong>the</strong>r functions<br />

which are fundamental for <strong>the</strong> various ecosystems <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong> environment in general. Freshwater<br />

systems have <strong>the</strong> major role <strong>to</strong> feed aquifers which in turn supply ground water sources. <strong>The</strong>y are also<br />

responsible for insuring water quality, as well as regulating floods. Moreover, well functioning freshwater<br />

systems are a precondition for maintaining biodiversity. Indeed, freshwater systems are <strong>the</strong> habitat <strong>of</strong> a<br />

great variety <strong>of</strong> species with 12% <strong>of</strong> all animal species living in <strong>the</strong>m <strong>and</strong> many more depending on <strong>the</strong>m<br />

for <strong>the</strong>ir survival. <strong>The</strong> richness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se ecosystems is especially important considering that <strong>the</strong>y only<br />

cover a tiny part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global surface. 8<br />

v. A special look at wetl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Wetl<strong>and</strong>s play an essential role in freshwater ecosystems. <strong>The</strong>y help <strong>to</strong> regulate water levels within<br />

watersheds. <strong>The</strong>y also provide carbon s<strong>to</strong>rage, water purification, <strong>and</strong> goods such as food, timber, etc.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are important spawning <strong>and</strong> nursery areas <strong>and</strong> provide plants for food <strong>and</strong> medicinal needs. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

serve as filter against pollution improving water quality. <strong>The</strong>y help control floods <strong>and</strong> damages caused<br />

by s<strong>to</strong>rms.<br />

3. Damage <strong>to</strong> Freshwater systems due <strong>to</strong> human activities<br />

Overuse <strong>and</strong> pollution <strong>of</strong> surface <strong>and</strong> groundwater threaten <strong>the</strong> prospects for human living conditions.<br />

Moreover <strong>the</strong>y restrict diversity <strong>and</strong> productivity in <strong>the</strong> ecosystems <strong>to</strong> an increasing degree. <strong>Water</strong><br />

consumption has strongly increased mainly owing <strong>to</strong> agricultural overuse, but also because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

growing population – in particular in <strong>the</strong> urban centres. Severe conflicts over water use are already<br />

appearing on <strong>the</strong> horizon <strong>the</strong> regions presently lacking water. Experts have identified water as a major<br />

challenge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 21 st century, with new conflicts emerging for control over water supplies, <strong>and</strong> because<br />

<strong>of</strong> increasing demographic pressure on scarce water resources.<br />

i. Stress on water supplies<br />

<strong>Water</strong> is vital <strong>to</strong> human beings as drinking water <strong>and</strong> in food production. <strong>Water</strong> resources, however, are<br />

not unlimited. Human activities have largely contributed <strong>to</strong> endanger world water supplies as <strong>to</strong> quantity<br />

<strong>and</strong> quality.<br />

Both surface <strong>and</strong> ground water supplies are threatened. Reasons for <strong>the</strong> alarming state <strong>of</strong> freshwater<br />

resources are various <strong>and</strong> numerous. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main reason is population growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is<br />

increasing per capita consumption through <strong>the</strong> proliferation <strong>of</strong> water-intense life-styles. <strong>The</strong> quantity <strong>and</strong><br />

quality <strong>of</strong> water available from freshwater systems is deeply altered by <strong>the</strong> modifications which humans<br />

operate in <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. Building <strong>of</strong> human settlements including cities, industrial facilities, dams <strong>and</strong><br />

roads, as well as agriculture have a great influence on <strong>the</strong> water supplies <strong>and</strong> on water cycles.<br />

ii. Threats <strong>to</strong> water quantity<br />

Each year, human beings withdraw about 4,000 km 3 <strong>of</strong> water, which represents about 20% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

normal (nonflood) flow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’s rivers. 9 <strong>The</strong> situation is all <strong>the</strong> more alarming since human<br />

withdrawals increase very fast, faster than <strong>the</strong> demographic growth. 10<br />

FIAN International 105<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

Human pressure on water supplies are not <strong>the</strong> same everywhere. Some regions are more particularly<br />

affected <strong>and</strong> threatened by scarcity than o<strong>the</strong>rs, unfortunately those regions are <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> ones<br />

experiencing fast population growth or are already dry areas. Projections estimate that water scarcity<br />

will concern half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population in <strong>the</strong> world by 2025. River basins such as <strong>the</strong> ones <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Volta, Nile<br />

<strong>and</strong> Narmada rivers will be among <strong>the</strong> most affected by water stress. 11<br />

Population growth is not <strong>the</strong> only threat <strong>to</strong> water quantity. Modern schemes <strong>of</strong> agricultural production<br />

imply a huge use <strong>of</strong> water especially for irrigation purposes. Industry is also a great consumer <strong>of</strong><br />

freshwater. Freshwater systems <strong>and</strong> water cycles are affected by human activities such as canalization<br />

<strong>and</strong> dams. River flows are slowed down through fragmentation (by dams <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r facilities) <strong>and</strong><br />

overextraction <strong>of</strong> water <strong>to</strong> such an extent that several big world rivers do not reach <strong>the</strong> sea any longer<br />

during <strong>the</strong> dry season. Dams <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir reservoirs have a fur<strong>the</strong>r negative impact on freshwater systems<br />

since <strong>the</strong>y strongly affect soil fertility by preventing sediments <strong>to</strong> be carried <strong>and</strong> disseminated<br />

downstream. Today, free-flowing rivers have become rare <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> world major rivers are canalized,<br />

diverted from <strong>the</strong>ir original wetl<strong>and</strong>s or floodplains, fragmented in reservoirs. All this has a very negative<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> balance <strong>and</strong> cycles <strong>of</strong> freshwater systems as well as on o<strong>the</strong>r ecosystems <strong>and</strong> entire<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes.<br />

As far as groundwater is concerned, excessive pumping from <strong>the</strong> aquifers leads <strong>to</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> s<strong>to</strong>rage<br />

capacity, <strong>of</strong> renewal <strong>and</strong> filtration capacities. <strong>The</strong> damage on aquifers can even have consequences on<br />

<strong>the</strong> soil layer above <strong>the</strong>m by creating serious terrain alterations.<br />

iii. Threats <strong>to</strong> water quality<br />

In industrialized countries, surface water quality has improved during <strong>the</strong> last decades thanks <strong>to</strong><br />

recycling <strong>and</strong> pollution control facilities. None<strong>the</strong>less, water contamination due <strong>to</strong> nitrate <strong>and</strong> pesticide<br />

persists. Chemical contamination <strong>and</strong> water quality degradation are a common feature <strong>to</strong> all regions in<br />

<strong>the</strong> world. Inorganic <strong>and</strong> organic compounds, (sometimes pathogens) attack water quality, menacing<br />

human <strong>and</strong> wildlife health. Groundwater contamination is due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> human use <strong>of</strong> contaminants such<br />

as oil, road salts <strong>and</strong> chemicals. <strong>The</strong>se contaminants get in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> groundwater, which becomes unsafe<br />

for human consumption. Diseases due <strong>to</strong> poor water quality spread.<br />

iv. Threats <strong>to</strong> food production<br />

As we have seen, inl<strong>and</strong> fisheries are essential <strong>to</strong> a great part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world population <strong>to</strong> feed<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves. Following demographic growth, food needs increase <strong>and</strong> overcatching becomes acute<br />

danger. Harvests have increased significantly in recent decades <strong>and</strong> are estimated <strong>to</strong> continue<br />

developing. According <strong>to</strong> FAO data in 1997, more than 7.7 million <strong>to</strong>nnes <strong>of</strong> fish were caught in lakes,<br />

rivers, swamps, marshes, water reservoirs <strong>and</strong> ponds, which represents some 6% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal world fish<br />

production. Catches are especially high in China, where <strong>the</strong> production amounts <strong>to</strong> some 1.8 million<br />

<strong>to</strong>nnes. 12 Freshwater ecosystems already face such severe attacks that <strong>the</strong>ir ability <strong>to</strong> support wild fish<br />

s<strong>to</strong>cks is strongly reduced. In order <strong>to</strong> cope with <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> a growing dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> a limited <strong>and</strong><br />

more <strong>and</strong> more threatened supply, aquaculture is booming.<br />

v. Habitat degradation: Threats on freshwater biodiversity<br />

Damage suffered by freshwater systems are threats for species living in <strong>and</strong> depending on <strong>the</strong>se<br />

systems. In addition <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> general alteration <strong>and</strong> overuse <strong>of</strong> water supplies, overharvesting <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> nonnative species belong <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> great menace. <strong>The</strong> following figures illustrate this<br />

dramatic erosion <strong>of</strong> biodiversity that is already taking place. More than 20% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’s 10.000<br />

freshwater fish species have become extinct, or threatened. In <strong>the</strong> USA, 37% <strong>of</strong> freshwater fish species,<br />

67% <strong>of</strong> mussels, 51% <strong>of</strong> crayfish <strong>and</strong> 40% <strong>of</strong> amphibians are affected. 13<br />

vi. Conversion <strong>of</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Conversion particularly affects wetl<strong>and</strong>s which have been drained <strong>and</strong> converted <strong>to</strong> farml<strong>and</strong>, filled for<br />

human settlements <strong>and</strong> economic activities. Wetl<strong>and</strong>s also experience heavy pollution <strong>and</strong> overuse <strong>of</strong><br />

FIAN International 106<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir waste processing capacity. <strong>The</strong>re is a lack <strong>of</strong> data on <strong>the</strong> original surface covered by wetl<strong>and</strong>s but<br />

a consensus seems <strong>to</strong> exist on <strong>the</strong> alarming extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir disappearance. It is also clear that<br />

conversion through drainage, deep alteration <strong>of</strong> surface <strong>and</strong> groundwater, added <strong>to</strong> fragmentation <strong>and</strong><br />

diversion <strong>of</strong> rivers have greatly affected <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>to</strong> provide <strong>the</strong>ir fundamental services <strong>and</strong><br />

goods such as agricultural l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> water filtration.<br />

References:<br />

• (2000) UNDP, UNEP, World Bank <strong>and</strong> World Resources Institute, World Resources 2000-2001 :<br />

People <strong>and</strong> ecosystems: <strong>The</strong> fraying web <strong>of</strong> life, World Resources Institute 2000, Washing<strong>to</strong>n DC<br />

• (1997), Shiklomanov I. A., Comprehensive Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> freshwater resources <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world:<br />

Assessment <strong>of</strong> water resources <strong>and</strong> water availability in <strong>the</strong> world. S<strong>to</strong>ckholm, Sweden:WMO <strong>and</strong><br />

S<strong>to</strong>ckholm Environment Institute.<br />

• (1997), World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), Comprehensive Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Freshwater<br />

Resources <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World. Geneva.<br />

• (1998), International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD), World Register <strong>of</strong> Dams 1998, Paris.<br />

• (1990), L´vovich M.I. <strong>and</strong> White G. F., Use <strong>and</strong> transformation <strong>of</strong> terrestrial water systems. Pp:235-<br />

252 in <strong>The</strong> Earth as Transformed by Human Action:Global <strong>and</strong> Regional Changes in <strong>the</strong> Biosphere<br />

over <strong>the</strong> past 300 years. Turner B. L., Clark W. C., Kateset R. W. al, eds. Cambridge University<br />

Press.<br />

• (1996), Abramovitz J. N., Imperiled <strong>Water</strong>, Impoverished future: <strong>The</strong> decline <strong>of</strong> freshwater<br />

ecosystems. WorldWatch Paper 128. Washing<strong>to</strong>n, D. C.: Worldwatch Institute.<br />

• (1990), Dahl T. E., Wetl<strong>and</strong> losses in <strong>the</strong> United States 1780 <strong>to</strong> 1980s, Washing<strong>to</strong>n D. C.:U.S.<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Interior, Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Service.<br />

• (1999), Europeen Environment Agency (EEA), Environment in <strong>the</strong> European Union at <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

century, Environmental Assessment Report No. 2. Copenhagen.<br />

• (1997), Myers N., <strong>The</strong> rich diversity <strong>of</strong> biodiverstiy issues. Pp: 125-138 in Biodiversity II.<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> Protecting our Biological Resources. Reaka-Kudla M. L., Wilson D. E. <strong>and</strong><br />

Wilson E. O., eds. Washing<strong>to</strong>n D.C.:Joseph Henry Press<br />

• (2000), Brunner J. et al. <strong>Water</strong> Scarcity, <strong>Water</strong> Resources Management <strong>and</strong> Hydrological<br />

Moni<strong>to</strong>ring (Draft). Unpublished Report. Washing<strong>to</strong>n D.C.:World Resources Institute<br />

• Wetl<strong>and</strong>s: Several definitions: http://h2osparc.wq.ncsu.edu/info/wetl<strong>and</strong>s/definit.html<br />

• Issues-Freshwater, United Nation Sustainable Development: www.un.org/esa/sustdev<br />

• US Energy Information Agency, www.eia.doe.gov / International Energy Outlook 2001<br />

• <strong>Water</strong>Webs. <strong>Water</strong>sheds, lakes, rivers, streams: www.eco-pros.com/waterwebs.htm<br />

• Economic Benefits <strong>of</strong> Wetl<strong>and</strong>s: www.epa.gov/owow/wetl<strong>and</strong>s/facts/fact4.html<br />

• Policy paper for <strong>the</strong> Bonn International Conference on Freshwater 2001, Forum Umwelt und<br />

Entwicklung: www.foumue.de/forumaktuell/positionspapiere/0000001e.html<br />

• FAO Fisheries database www.fao.org/fi<br />

FIAN International 107<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

B. Basics on Biodiversity<br />

1. Types <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity<br />

Biological diversity or biodiversity is a term that is used <strong>to</strong> describe <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> living beings, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

relationships <strong>to</strong> each o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> interactions with <strong>the</strong>ir environment. Biodiversity encompasses several<br />

different levels <strong>of</strong> biological organization, from <strong>the</strong> very specific <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> most general, which form a<br />

hierarchy <strong>of</strong> categories:<br />

i. Genetic diversity: <strong>The</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> biological diversity is formed by <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> information contained in<br />

<strong>the</strong> genes <strong>of</strong> specific organisms. This covers distinct populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same species (such as <strong>the</strong><br />

thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> traditional rice varieties in India) or genetic variation within a population. Different<br />

combinations <strong>of</strong> genes within organisms, or <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> different variants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same basic gene<br />

are <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> evolution. <strong>The</strong> wealth <strong>of</strong> life on earth <strong>to</strong>day is <strong>the</strong> product <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong><br />

years <strong>of</strong> this evolutionary his<strong>to</strong>ry.<br />

ii. Species diversity: At <strong>the</strong> next hierarchical level is <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> different species that exist on Earth.<br />

A concept that includes not only <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species in a region – its “species richness” - but also <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship <strong>of</strong> different groups <strong>of</strong> species <strong>to</strong> each o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

iii. Ecosystem diversity: Biodiversity also describes <strong>the</strong> varied composition <strong>of</strong> ecosystems <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

variety <strong>of</strong> different sorts <strong>of</strong> ecosystems.<br />

<strong>The</strong> knowledge about <strong>the</strong> world’s life forms lags surprisingly far behind o<strong>the</strong>r fields <strong>of</strong> scientific inquiry.<br />

While a great deal is known about individual species <strong>of</strong> bird, fish, mammals <strong>and</strong> plants, <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal number<br />

<strong>of</strong> species that inhabit <strong>the</strong> planet remains unknown. <strong>The</strong> UNEP Global Biodiversity Assessment uses an<br />

estimate <strong>of</strong> about 13 million, but <strong>the</strong> range varies from 8 <strong>to</strong> 50 million or more, out <strong>of</strong> which only about 2<br />

million species have been described scientifically or studied in detail. Never<strong>the</strong>less it is not necessary <strong>to</strong><br />

know <strong>the</strong> exact number <strong>of</strong> species <strong>to</strong> be concerned about <strong>the</strong> rates at which <strong>the</strong> documented species<br />

are now disappearing or even already disappeared from our world. Today, most extinction will occur<br />

before <strong>the</strong> species have even been named <strong>and</strong> described or known ecologically.<br />

2. Human benefits from biodiversity<br />

All life on earth is part <strong>of</strong> one great, interdependent system. It interacts with <strong>and</strong> depends on <strong>the</strong> nonliving<br />

components <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> planet like atmosphere, oceans, freshwater, rocks <strong>and</strong> soils. Humanity<br />

depends <strong>to</strong>tally on this community <strong>of</strong> life, this biosphere: Many essential goods for human societies<br />

derive from <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> natural ecosystems; including seafood, game animals, fodder, fuelwood <strong>and</strong><br />

timber. But natural ecosystems also perform fundamental life support services like <strong>the</strong> purification <strong>of</strong> air<br />

<strong>and</strong> water, de<strong>to</strong>xification <strong>and</strong> decomposition <strong>of</strong> wastes, regulation <strong>of</strong> climate, regeneration <strong>of</strong> soil fertility,<br />

<strong>and</strong> last but not least <strong>the</strong> production <strong>and</strong> maintenance <strong>of</strong> biodiversity, from which key ingredients <strong>of</strong> our<br />

agricultural, pharmaceutical, <strong>and</strong> industrial enterprises are derived. Hence <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

organisms, <strong>the</strong> biological diversity is a direct source <strong>of</strong> ecosystem goods <strong>and</strong> is <strong>the</strong> blanket term for <strong>the</strong><br />

natural biological wealth that sustains human life <strong>and</strong> well-being.<br />

Our lifes depend on biodiversity in ways that are not <strong>of</strong>ten appreciated. It is well unders<strong>to</strong>od by most<br />

people that we rely on <strong>the</strong> earth’s non-renewable resources <strong>of</strong> oil <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r fuel <strong>and</strong> non-fuel minerals<br />

Due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> technological advances that dominate our lives, we can easily forget <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>to</strong> which <strong>the</strong><br />

modern, industrial world is embedded in <strong>the</strong> biological world. Ecosystem services operate on such a<br />

FIAN International 108<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

gr<strong>and</strong> scale <strong>and</strong> in such intricate <strong>and</strong> little-explored ways that most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m cannot be replaced by<br />

technology.<br />

i. <strong>Food</strong>-supply:<br />

“Agricultural biodiversity” is a vital part <strong>of</strong> biodiversity. It is a creation <strong>of</strong> humankind whose food security<br />

depends on <strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biological resources that are important for food <strong>and</strong> agriculture.<br />

Those food crops <strong>and</strong> lives<strong>to</strong>cks are part <strong>of</strong> biodiversity, just like <strong>the</strong>ir wild relatives. Farmers bred <strong>and</strong><br />

maintained a tremendous diversity <strong>of</strong> crop varieties around <strong>the</strong> world until this century. Never<strong>the</strong>less out<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 30000 <strong>to</strong>day known edible plant species, human beings have only utilized around 7000 plant<br />

species for food over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> which no more than 120 are cultivated <strong>to</strong>day on a larger<br />

scale: 90 provide 5 % <strong>of</strong> human food, 21 provide 20 % <strong>of</strong> human food, 9 provide 75 % <strong>of</strong> human food. 14<br />

On-farm diversity is shrinking fast, due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> planting <strong>of</strong> comparatively fewer varieties <strong>of</strong> crops that<br />

respond better <strong>to</strong> water, fertilizers <strong>and</strong> pesticides. This has lead <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact, that in <strong>to</strong>day’s world 75% <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> human food supply actually depends on only 9 plant species.<br />

ii. Biodiversity as “food insurance”<br />

Biodiversity is a form <strong>of</strong> ecosystem health insurance: Ecosystems that include several species fulfilling<br />

<strong>the</strong> same or similar functions are more resistant <strong>to</strong> environmental stress <strong>and</strong> recover faster from<br />

perturbations. This is due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> genetic variety, through which every species ecan respond with<br />

different adaptabilities <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>lerances. Ecosystems that have lost ei<strong>the</strong>r genetic or species diversity are<br />

similar <strong>to</strong> monocultures <strong>and</strong> less resistant <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> environmental perturbations, such as<br />

droughts, soil salinity, pests <strong>and</strong> diseases. Regarding <strong>the</strong> food supply mentioned above, <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong><br />

genetic or species variety could thus have a great impact on human food security. Problems with any <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 9 plant species covering 75 % <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human food supply, this could lead <strong>to</strong> food shortages <strong>and</strong><br />

hunger on a large scale. Hence biodiversity is not only an ecosystem health insurance but also an<br />

insurance for our food security <strong>and</strong> is <strong>the</strong>refore vitally important for <strong>the</strong> right <strong>to</strong> food.<br />

iii. Medicinal resources<br />

Four out <strong>of</strong> every five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>p 150 prescription drugs used in <strong>the</strong> U.S. are based on natural<br />

compounds. 74% on plants, 18% on fungi, 5% on bacteria, <strong>and</strong> 3% on one vertebrate (snake) species.<br />

(Grifo <strong>and</strong> Rosenthal, as cited in Dobson 1995). A famous example is aspirin - a derivative <strong>of</strong> salicylic<br />

acid which was first taken from <strong>the</strong> bark <strong>of</strong> willow trees. Looking at <strong>the</strong> global situation, it has been<br />

estimated that 80% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human population relies on plant-based medicines for <strong>the</strong>ir primary health<br />

care, <strong>and</strong> about 85% <strong>of</strong> traditional medicine involves <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> plant extracts (Farnsworth et al. 1985).<br />

Yet it is estimated that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> approximately 270000 plant species, only less than half <strong>of</strong> 1% have been<br />

screened for <strong>the</strong>ir beneficial pharmaceutical properties.<br />

Consequentially, in connection with medicinal resources, again biodiversity plays a vital role. Different<br />

populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same species may produce different types <strong>of</strong> defensive chemicals that have potential<br />

use as pharmaceuticals. It is <strong>the</strong>refore obvious that <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> species will also result in a severe loss <strong>of</strong><br />

medicinal resources.<br />

3. Damage <strong>to</strong> biodiversity due <strong>to</strong> human activities:<br />

Ecosystem services are essential for guaranteeing food security, health <strong>and</strong> well-being for citizens in all<br />

societies. Never<strong>the</strong>less human activities are already impairing <strong>the</strong> flow <strong>of</strong> ecosystem services on a large<br />

scale, due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> continued degradation <strong>and</strong> erosion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resource on which <strong>the</strong>y are based, which is<br />

biodiversity.<br />

It will take at least decades until depleted marine resources can regenerate. <strong>The</strong> same is true for forests<br />

– unless <strong>the</strong> soils have been washed away. It will take at least hundreds <strong>of</strong> years <strong>to</strong> rebuild just a few<br />

centimeters <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>psoil. 15 A species lost, however, is lost forever.<br />

FIAN International 109<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

<strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> biodiversity is measured in terms <strong>of</strong> destruction <strong>and</strong> fragmentation <strong>of</strong> habitats as well as in<br />

species extinction. Some estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> species loss are about 100 per day predicting <strong>the</strong><br />

disappearance <strong>of</strong> more than a quarter <strong>of</strong> all species within <strong>the</strong> next 50 years. Unfortunately <strong>the</strong>se<br />

numbers exceed <strong>the</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> new species by a fac<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> 10.000 or more. <strong>The</strong> disappearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> any specie is a critical endpoint, marking <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> 3.5 billion years <strong>of</strong> evolutionary development.<br />

Each species is a reservoir <strong>of</strong> unique genetic information that cannot be reproduced once it is gone. In<br />

this broader sense, any extinction, however trivial it may seem, represents a permanent loss <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

biosphere as a whole.<br />

<strong>The</strong> extinction <strong>of</strong> species is only <strong>the</strong> final act in a process driven by unsustainable human economies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> local populations <strong>of</strong> species disrupts <strong>the</strong> sensitive web <strong>of</strong> interactions <strong>and</strong>, as mentioned<br />

above, causes <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> different ecosystem services essential for civilization. Undisturbed<br />

ecosystems have shrunk dramatically in area over <strong>the</strong> past decades as human population <strong>and</strong> resource<br />

consumption have grown. 98% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tropical dry forest along Central America´s Pacific coast has<br />

disappeared. Thail<strong>and</strong> lost 84% <strong>of</strong> its mangroves since 1975 <strong>and</strong> virtually none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> remainder is<br />

undisturbed (overall it is estimated that half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’s mangroves forests has been destroyed). In<br />

freshwater ecosystems, dams have destroyed large sections <strong>of</strong> river <strong>and</strong> stream habitats. In marine<br />

ecosystems, coastal development has wiped out reef <strong>and</strong> near-shore communities. In tropical forests, a<br />

major cause <strong>of</strong> forest loss is <strong>the</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> agriculture, though in specific regions commercial timber<br />

harvest may pose an even greater problem.<br />

i. Habitat Loss <strong>and</strong> Fragmentation<br />

Destruction <strong>and</strong> fragmentation <strong>of</strong> habitats caused by l<strong>and</strong>-use changes are probably <strong>the</strong> principal<br />

contribu<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> biodiversity. About 1%-2% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> earth’s l<strong>and</strong> surface is used for urban<br />

purposes, but o<strong>the</strong>r l<strong>and</strong> acquisitions, especially for agriculture, far exceed <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> sealed<br />

by urbanisation: Homo sapiens has already converted about a quarter <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> surface <strong>to</strong><br />

agricultural uses. <strong>The</strong> expansion <strong>of</strong> agricultural l<strong>and</strong> has <strong>of</strong>ten been at <strong>the</strong> expense <strong>of</strong> species-rich<br />

forests <strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s which sustain a much bigger biodiversity than agriculturally used areas.<br />

Agricultural l<strong>and</strong> acquisition mainly focuses on those areas with <strong>the</strong> most favourable environmental<br />

conditions, like fertile soils, which are <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> greatest biological diversity. As much as<br />

30% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> potential area <strong>of</strong> temperate, subtropical, <strong>and</strong> tropical forest has been lost <strong>to</strong> agriculture<br />

though conversion <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-use changes, accompanied by <strong>the</strong> extinction <strong>of</strong> a multitude <strong>of</strong> local species.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ecological impact <strong>of</strong> agriculture, however, largely depends on <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> agriculture applied.<br />

ii. Industrial agriculture - agribusiness<br />

Industrial agriculture is based on a strictly limited number <strong>of</strong> varieties where breeders cultivate just a few<br />

high-yielding but uniform crops. Linked <strong>to</strong> agribusiness is <strong>the</strong> need for massive fertilization <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> monocultures which are vulnerable <strong>to</strong> diseases <strong>and</strong> pests. <strong>The</strong>se trends are strongly<br />

promoted in <strong>the</strong> South as well due <strong>to</strong> policies which integrate sou<strong>the</strong>rn agricultural systems in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

world market. Large-scale plantations (or dependent contract farmers) grow only a narrow range <strong>of</strong><br />

crops like c<strong>of</strong>fee, cocoa <strong>and</strong> bananas. As a consequence <strong>of</strong> agribusiness <strong>the</strong> cultivation <strong>of</strong> a multitude <strong>of</strong><br />

well adapted local varieties has been ab<strong>and</strong>oned <strong>and</strong> already lead <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> entire loss <strong>of</strong> some varieties <strong>of</strong><br />

non-commercial crops. Toge<strong>the</strong>r with this shrinkage <strong>of</strong> plant species, <strong>the</strong>re is a decline <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complex<br />

network <strong>of</strong> supporting species, like pollina<strong>to</strong>rs or seed dispensers.<br />

In addition, <strong>the</strong> privatization <strong>of</strong> genetic resources that have been engineered <strong>and</strong> patented accelerates<br />

<strong>the</strong> trend <strong>to</strong>ward monocultural cropping. Just a h<strong>and</strong>ful <strong>of</strong> varieties <strong>of</strong> patented hybrid corn now cover<br />

millions <strong>of</strong> acres <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> midwestern U.S. corn belt, at <strong>the</strong> expense <strong>of</strong> prairies which once hosted<br />

thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> varieties <strong>of</strong> grasses supporting birds <strong>and</strong> butterflies, bees <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r life. Similarly will <strong>the</strong><br />

biodiversity <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r areas shrink as patented crops take over.<br />

FIAN International 110<br />

June 2002

Starving <strong>the</strong> Future <strong>Study</strong> 3<br />

Of particular importance for biodiversity are also <strong>the</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> auxiliary means <strong>of</strong> industrial<br />

agriculture: Heavy applications <strong>of</strong> fertilizers <strong>and</strong> pesticides are causing environmental problems <strong>and</strong><br />

affect <strong>the</strong> abundance <strong>and</strong> viability <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r plants <strong>and</strong> animals in this areas. Intensively used fields lead<br />

<strong>to</strong> a run-<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> pesticides <strong>and</strong> herbicides which results in adverse effects on o<strong>the</strong>r non-target species.<br />

Huge fields suitable for heavy agribusiness machines destroy <strong>the</strong> bushes <strong>and</strong> trees which had been<br />

important habitats in different agricultural systems. <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> heavy machines leads <strong>to</strong> large scale<br />

destruction <strong>of</strong> animal life in <strong>the</strong> fields. Loss <strong>of</strong> organic life in <strong>the</strong> soils accelerates erosion through wind<br />

<strong>and</strong> water.<br />

iii. Industrial forestry<br />

Forests are particularly important ecosystems for biodiversity since <strong>the</strong>y harbor about two-thirds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

known terrestrial species, have <strong>the</strong> highest species diversity <strong>and</strong> endemism <strong>of</strong> any ecosystem, as well<br />

as <strong>the</strong> highest number <strong>of</strong> threatened species. But similar trends as in industrial agriculture transforms<br />

<strong>the</strong> diverse forest ecosystems in<strong>to</strong> high-yielding monocultural tree plantations, <strong>and</strong> even fewer tree<br />

genes than crop genes have been preserved <strong>of</strong>f-site in gene banks as an insurance policy against<br />

disease <strong>and</strong> pests.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Global Biodiversity Assessment conducted in 1995 under <strong>the</strong> auspices <strong>of</strong> UNEP found that if recent<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> tropical forest loss continue for <strong>the</strong> next 25 years, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species in forests would be<br />

reduced by approximately 4-8%.<br />

iv. Over-exploitation <strong>of</strong> plant <strong>and</strong> animal species<br />

Numerous biological resources have been over-exploited, sometimes <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> extinction. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

overfishing, overhunting, overpicking, overgrazing <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> like. <strong>The</strong> extinction rate is increasing, making<br />

it al<strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r possible that well over half <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> species, which still remain will have disappeared by <strong>the</strong><br />