5. the cumbria tarns project - FreshwaterLife

5. the cumbria tarns project - FreshwaterLife

5. the cumbria tarns project - FreshwaterLife

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

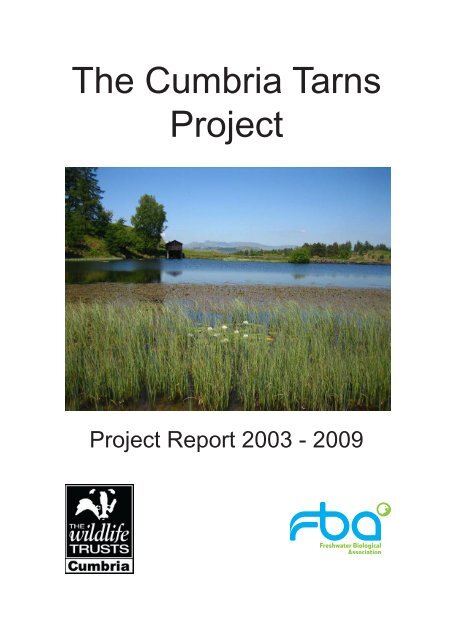

The Cumbria Tarns<br />

Project<br />

Project Report 2003 - 2009

1. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 6<br />

2. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 8<br />

2.1. What is a tarn? .............................................................................................................. 8<br />

2.2. How were <strong>the</strong>y formed? ............................................................................................. 9<br />

3. THE DIVERSITY AND FLORA OF TARNS .................................................................... 11<br />

3.1. Upland (oligotrophic) <strong>tarns</strong> ..................................................................................... 11<br />

3.2. Lowland <strong>tarns</strong> ............................................................................................................. 12<br />

4. ARE SMALL WATER BODIES IMPORTANT AND ARE THEY THREATENED? .. 14<br />

<strong>5.</strong> THE CUMBRIA TARNS PROJECT .................................................................................... 16<br />

<strong>5.</strong>1. When and why was it set up? .................................................................................. 16<br />

<strong>5.</strong>2. Pillwort survey ........................................................................................................... 17<br />

<strong>5.</strong>3. O<strong>the</strong>r surveys ............................................................................................................. 17<br />

<strong>5.</strong>4. Raising awareness ..................................................................................................... 18<br />

6. VOLUNTEERS ........................................................................................................................ 19<br />

6.1. The importance of volunteers to <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> ........................................................ 19<br />

6.2. Training volunteers ................................................................................................... 20<br />

6.3. The role of <strong>the</strong> Project officer .................................................................................. 20<br />

7. TARNS SURVEY METHOD ................................................................................................ 21<br />

7.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 21<br />

7.2. Survey method ........................................................................................................... 21<br />

8. TARN SURVEY RESULTS .................................................................................................... 23<br />

8.1. Key achievements ...................................................................................................... 23<br />

8.2. Data analysis ............................................................................................................... 23<br />

8.3. Results and conclusions of first analysis .............................................................. 24<br />

9. THE FUTURE .......................................................................................................................... 26<br />

9.1. How will <strong>the</strong> information be used? ....................................................................... 26<br />

9.2. Future management................................................................................................... 26<br />

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................. 28<br />

11. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING .......................................................................... 29

CUMBRIA TARNS PROJECT TIMELINE<br />

2003 The Cumbria Tarns Project, initiated by Cumbria Wildlife Trust (CWT) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Freshwater Biological Association (FBA) as part of CWT’s Community<br />

Action for Wildlife programme. The objectives were to repeat <strong>the</strong> tarn<br />

surveys carried out by Ralph Stokoe in <strong>the</strong> 1970’s and provide volunteers<br />

with an opportunity to gain experience in surveying freshwater habitats.<br />

2004 Pilot survey undertaken giving volunteers training in freshwater habitat<br />

survey methodology and plant identification.<br />

Twenty-five <strong>tarns</strong> surveyed and <strong>the</strong> data entered into <strong>the</strong> Tarns and Ponds<br />

database.<br />

Seed corn funding secured from English Nature (EN)/Natural England (NE),<br />

Environment Agency (EA) and National Trust (NT), to extend <strong>the</strong> survey<br />

into <strong>the</strong> 2005 season.<br />

2005 Tarns Project Officer appointed to undertake surveys and support volunteer<br />

survey team.<br />

Tarns Project Handbook produced setting out <strong>the</strong> tarn survey methodology.<br />

The survey team of 20 volunteers surveyed nearly 100 <strong>tarns</strong> and ponds.<br />

Funding secured from SITA and Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) to extend <strong>the</strong><br />

Project until <strong>the</strong> end of 2008, expanding <strong>the</strong> remit of <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> to contribute to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cumbria Biodiversity Action Plan with surveys of oligotrophic (nutrient<br />

poor) <strong>tarns</strong> and <strong>the</strong> scarce aquatic fern, pillwort (Pilularia globularia).<br />

2006 The <strong>tarns</strong> survey team carry out surveys at 96 <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

The Project surveys sites with historical records for pillwort, re-finding <strong>the</strong><br />

species at eight sites, and discovering it at two new sites.<br />

The Project carried out trial fish surveys with help from <strong>the</strong> EA, and <strong>the</strong><br />

Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH).<br />

2007 104 <strong>tarns</strong> surveyed.<br />

Fish surveys undertaken at six <strong>tarns</strong>, attracting a fur<strong>the</strong>r 11 volunteers to <strong>the</strong><br />

Project.<br />

An MSc Thesis, by Birmingham University student Tamsin Douglas compared<br />

plant data collected by <strong>the</strong> Tarns Project with <strong>the</strong> records collected by Stokoe<br />

in <strong>the</strong> late 1970s. Analysis of <strong>the</strong> data suggested that a number of changes in<br />

<strong>the</strong> tarn flora had occurred including a decline in species diversity.<br />

2008 The Wildlife Site Selection panel selected 19 tarn sites surveyed by <strong>the</strong> Project<br />

as new Wildlife Sites using new guidelines refined by <strong>the</strong> knowledge gained<br />

through Tarns <strong>project</strong> surveys.<br />

A fur<strong>the</strong>r 80 surveys completed including Broadcrag Tarn and Foxes Tarn,<br />

<strong>the</strong> highest named <strong>tarns</strong> in Lakeland.<br />

Tarns Project commissioned by <strong>the</strong> EA to undertake surveys of Windermere<br />

for aquatic plants and <strong>the</strong> Glutinous snail (Myxas glutinosa).

1. SUMMARY<br />

Tarns are a unique feature of Cumbria, contributing greatly to its beauty as well as<br />

being ecologically important. Cumbria has over 3,000 small water bodies, found from<br />

<strong>the</strong> rugged high fells to richer low lying agricultural land. The diversity in size, shape,<br />

altitude, depth and water chemistry means that many plants and animals find refuge<br />

and thrive in <strong>the</strong>se habitats. They support a huge variety of life, from microscopic<br />

forms to large vascular plants and animals, including fish, amphibians and birds.<br />

Toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> small water bodies support two-thirds of all freshwater plants (at least<br />

240 plant species are associated with <strong>tarns</strong> in Cumbria) and animal species found in<br />

<strong>the</strong> county, and support more invertebrates and rare species than rivers.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong>ir diversity and interest, small water bodies are often taken for granted and<br />

have received less protection and interest than rivers and lakes. Nationally, ponds have<br />

been disappearing at an alarming rate through drainage and in-filling. Results from<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK’s Countryside Survey 2007, carried out by <strong>the</strong> CEH, show that good quality,<br />

wildlife-rich ponds have gone from many parts of <strong>the</strong> countryside with only 8% of<br />

ponds across <strong>the</strong> UK currently in good condition and <strong>the</strong> biological quality of lowland<br />

ponds declining over <strong>the</strong> last decade.<br />

The ecological importance of Cumbria’s <strong>tarns</strong> has been recognised for many years.<br />

The FBA based on Windermere, has been carrying out scientific work on <strong>tarns</strong> for over<br />

70 years and <strong>the</strong> Brathay Exploration Group began studying <strong>tarns</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 1950’s. In<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1970’s a local naturalist, Ralph Stokoe, undertook botanical surveys of nearly 400<br />

<strong>tarns</strong> across Cumbria. His detailed records provide a valuable and extensive source of<br />

information.<br />

In 2003, CWT and <strong>the</strong> FBA set up <strong>the</strong> Cumbria Tarns Project. Its aim was to engage<br />

trained local volunteers in re-surveying <strong>tarns</strong> that had been surveyed 30 years<br />

previously by Ralph Stokoe. Repeating <strong>the</strong>se surveys has provided us with two sets<br />

of data that can be compared and analysed to assess whe<strong>the</strong>r species composition<br />

and tarn ecology has changed over <strong>the</strong> last 30 years, and help determine <strong>the</strong> possible<br />

causes of this change.<br />

An initial analysis of data has suggested a decline in species richness, particularly<br />

among <strong>the</strong> submerged and floating macrophyte species. The analysis also showed a<br />

shift in nutrient status in <strong>the</strong> lowland <strong>tarns</strong> towards more eutrophic conditions. In <strong>the</strong><br />

upland <strong>tarns</strong> <strong>the</strong>re was no detected change in ecology, however species richness has<br />

declined.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> has developed its remit has widened to include surveys of UK Biodiversity<br />

Action Plan (UKBAP) and Cumbria Biodiversity Action Plan (CBAP) habitats and<br />

species, particularly nutrient poor (oligotrophic) <strong>tarns</strong> and <strong>the</strong> scarce aquatic fern,<br />

pillwort (Pilularia globularia). We have also undertaken fish surveys and in 2008 carried<br />

out an aquatic plant survey of Windermere.

The Tarns Project is <strong>the</strong> widest ranging survey of aquatic plants in small water bodies<br />

in Cumbria since Ralph Stokoe’s in <strong>the</strong> 1970’s. In total we have collected data for 370<br />

<strong>tarns</strong>, including many that have not been previously studied in detail, <strong>the</strong>reby adding<br />

to <strong>the</strong> knowledge of <strong>the</strong> distribution of aquatic plant species, including some rarer<br />

species such as pillwort. We have collected information on a range of o<strong>the</strong>r biological<br />

and environmental data such as management and surrounding landscape.<br />

This information provides an invaluable resource, which can be used to fur<strong>the</strong>r protect<br />

<strong>tarns</strong>, particularly through appropriate management. The owners of <strong>tarns</strong> have been<br />

sent details of <strong>the</strong> survey and organisations involved in scientific, conservation and<br />

environmental protection work can access <strong>the</strong> information using a geographical<br />

mapping system and <strong>the</strong> Tarns and Ponds database.

2. INTRODUCTION<br />

Cumbria is famous for its lakes, which are prominent features of <strong>the</strong> main valleys, yet<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are many more <strong>tarns</strong>. Cumbria is one of <strong>the</strong> most important counties in England<br />

for small water bodies, <strong>the</strong>re being an estimated 3,000+ <strong>tarns</strong> and pools in <strong>the</strong> county.<br />

It is difficult to know <strong>the</strong> exact number because landscapes change and many pools are<br />

temporary. Based at Ferry House, adjacent to <strong>the</strong> Windermere ferry landing, <strong>the</strong> FBA<br />

has been carrying out research into <strong>the</strong> freshwaters in <strong>the</strong> Lake District since 1929 and<br />

some of its work has had far-reaching implications for water management and supply.<br />

For example, <strong>the</strong> experiments in Blelham Tarn influenced <strong>the</strong> design of water storage<br />

reservoirs in <strong>the</strong> UK and abroad. The Brathay Exploration Group began studying<br />

<strong>tarns</strong> in <strong>the</strong> 1950’s, collecting data on <strong>the</strong> shape and depth of <strong>tarns</strong>, and analysing <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

sediments, which has helped us understand how <strong>the</strong>y were formed.<br />

Staff at <strong>the</strong> FBA have examined animal and plants in <strong>tarns</strong> for over 70 years but <strong>the</strong><br />

most comprehensive survey of <strong>the</strong> flora of <strong>tarns</strong> of Cumbria was undertaken by Ralph<br />

Stokoe, an FBA member and amateur naturalist, who, between February 1975 and<br />

December 1980, surveyed 378 <strong>tarns</strong>, visiting many of <strong>the</strong>m several times. He recorded<br />

over 200 plant species in total and <strong>the</strong> results of his work have been collated from his<br />

meticulous field diary and record cards and published by <strong>the</strong> FBA (Stokoe, 1983.)<br />

In 1983, a survey of macrophytes, Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), and gastropod<br />

molluscs of 46 water bodies in Cumbria was undertaken as part of an MSc dissertation<br />

(commissioned by Nature Conservancy Council, a predecessor body of EN and NE.<br />

The author produced a classification scheme for <strong>tarns</strong> based on an analysis of 76 <strong>tarns</strong><br />

(Charter, 1984).<br />

2.1. What is a tarn?<br />

The word ‘tarn’ is derived from <strong>the</strong> Old Norse ‘tjorn’, which was used to describe any<br />

small body of water. It means ‘a small lake’ or more poetically ‘a teardrop’. Tarn is a<br />

regional term used largely, but not exclusively in <strong>the</strong> Lake District, which along with<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>r local names, originated with <strong>the</strong> Viking invaders who settled in Cumbria<br />

in <strong>the</strong> tenth century.<br />

There is no precise scientific definition for a Tarn. The dictionary defines <strong>the</strong>m as<br />

small, steep sided mountain lakes or pools and purists might add that <strong>the</strong> definition<br />

should include that a tarn is formed as a result of glacial activity. However, <strong>the</strong> term is<br />

used more generally in Cumbria to include ponds and small lakes in both upland and<br />

lowland areas and <strong>the</strong> Tarns Project adopted this broader meaning.

2.2. How were <strong>the</strong>y formed?<br />

Most <strong>tarns</strong> were formed as a result of glacial action. When <strong>the</strong> glaciers and ice sheets<br />

finally receded some 10,000 years ago, <strong>the</strong>y left a landscape of eroded hollows and<br />

valley bottoms broken with hummocks and mounds. The concentration of <strong>tarns</strong> in<br />

Cumbria owes everything to this scoured, undulating landscape where water can be<br />

trapped and contained.<br />

Many of <strong>the</strong> highest and most spectacular <strong>tarns</strong> e.g. Goat’s Water, occupy cirques<br />

scooped from <strong>the</strong> fells by ice and some are surprisingly deep. Blea Water on High<br />

Street, has a depth of 63 metres, only surpassed by Wastwater and Windermere, and is<br />

<strong>the</strong> finest example of a cirque lake in England. O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>tarns</strong> owe <strong>the</strong>ir existence to <strong>the</strong><br />

deposition of glacial moraines and debris that have dammed valley head streams.<br />

Goat’s Water, Coniston, lies in a long, south facing cirque.

Bogbean, an emergent plant of <strong>tarns</strong> and wet bogs. It has<br />

erect long-stalked trifoliate leaves (M. Fletcher, FBA).<br />

10<br />

Tarns also occur in areas of peat,<br />

for example on <strong>the</strong> Pennines in<br />

East Cumbria and <strong>the</strong> Solway<br />

plain, <strong>the</strong> smaller ones often being<br />

referred to as bog pools. These<br />

contain few plant species typically<br />

with bog moss (Sphagnum species),<br />

common cottongrass (Eriophorum<br />

angustifolium) and bogbean<br />

(Menyan<strong>the</strong>s trifoliata).<br />

Lower down, man’s influence<br />

is obvious, many <strong>tarns</strong> having<br />

been created by damming valleys<br />

or enlarged by raising <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

embankments to increase storage<br />

capacity for sporting or industrial purposes. Yew Tree Tarn near Coniston was created<br />

as a fishpond by <strong>the</strong> raising of a stone-faced concrete dam in <strong>the</strong> 1930’s. Barngates<br />

Tarn was also constructed in 1930’s to supply water to <strong>the</strong> Drunken Duck Inn and for<br />

fishing. Industries such as mining used <strong>the</strong> water resources from local rivers and <strong>tarns</strong><br />

as <strong>the</strong>ir main source of energy. Levers Water sits in <strong>the</strong> midst of <strong>the</strong> Langdale crags<br />

and has for centuries provided water for power and processing in <strong>the</strong> Coppermines<br />

valley near Coniston. Middle Fairbank Tarn and High Dam Tarn were used to power<br />

bobbin mills; once suppliers of wooden bobbins for <strong>the</strong> Lancashire cotton industry<br />

Bog pool on Torver Common.

3. THE DIVERSITY AND FLORA OF TARNS<br />

Cumbria has a diverse geology and landscape and a wide range of tarn types that vary<br />

in altitude, size, depth, permanence and water chemistry. Those set in high rock basins,<br />

like Angle Tarn, Blea Water, Red Tarn or Goat’s Water, may be <strong>the</strong> most spectacular, but<br />

lower and more richly vegetated waters like Loughrigg Tarn, Little Langdale Tarn or<br />

Blelham Tarn enhance <strong>the</strong> landscape of <strong>the</strong> valley floors.<br />

Standing waters are often classified according to <strong>the</strong>ir nutrient status commonly<br />

described by <strong>the</strong> terms oligotrophic (nutrient poor), mesotrophic (of intermediate<br />

nutrient status) and eutrophic (nutrient rich). The majority of Cumbria’s lakes and <strong>tarns</strong><br />

lie within an area formed of hard base-poor rocks that wea<strong>the</strong>r slowly and release few<br />

nutrients (mainly calcium, potassium, nitrogen and phosphorus) and are naturally<br />

oligotrophic or mesotrophic.<br />

Aquatic plants are difficult to define precisely since <strong>the</strong> boundary between <strong>the</strong> land and<br />

water is not fixed but fluctuates with <strong>the</strong> season and rainfall. However, a convenient<br />

definition is “plants which normally have at least <strong>the</strong>ir lower stems in water during <strong>the</strong> driest<br />

time of <strong>the</strong> year” (Halliday, 1999). They include true aquatics i.e. plants that will only<br />

grow in water, emergent plants, and aquatic forms of species also found out of water.<br />

Aquatic macrophytes are aquatic plants visible to <strong>the</strong> naked eye. They include vascular<br />

plants, some mosses and liverworts (bryophytes) and stoneworts (Characeae), which are<br />

large, structurally complex algae. Aquatic plants can be divided into three categories;<br />

submerged, free-floating and emergent.<br />

Aquatic plants have important roles in <strong>the</strong> structure and functioning of <strong>the</strong> ecosystem<br />

and can be used as indicators of <strong>the</strong> quality/health of <strong>the</strong> waterbody. They provide<br />

habitat and refuges for fauna, stabilise lake sediments, are integral parts of <strong>the</strong> food<br />

chain providing food for herbivorous animals and play an important role in nutrient<br />

cycling.<br />

3.1. Upland (oligotrophic) <strong>tarns</strong><br />

Upland, oligotrophic <strong>tarns</strong> (with low nutrient levels and low productivity) usually<br />

occur on hard, acid rocks. Their waters are cold and clear and <strong>the</strong>y support a poor<br />

but distinctive flora with characteristic narrow leaves, tough cuticles and ei<strong>the</strong>r tight<br />

rosettes of leaves or long linear leaves that offer little resistance to wave action. The<br />

tarn shores are mostly rocky and wave action in <strong>the</strong>se exposed situations means that<br />

floating-leaved or emergent plants are virtually absent or restricted to small sheltered<br />

bays. In <strong>the</strong> shallow waters, <strong>the</strong>re is typically a zone of shoreweed (Littorella uniflora),<br />

a small submerged plant with a rosette of bright green, narrow cylindrical leaves that<br />

typically develops dense carpets of plants joined by creeping and rooting runners.<br />

Scattered rosettes of <strong>the</strong> water lobelia (Lobelia dortmanna) often occur in this zone and<br />

<strong>the</strong> slender flowering stems with <strong>the</strong>ir pale blue flowers raised above <strong>the</strong> surface are a<br />

familiar sight in summer. In deeper water, but often overlapping with <strong>the</strong> shoreweed,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is usually a zone of quillwort (Isoetes lacustris). This too has rosettes with long<br />

cylindrical leaves. Also in this zone, are plants with long threadlike or fea<strong>the</strong>ry leaves<br />

such as alternate leaved water milfoil (Myriophyllum alterniflorum), bulbous rush (Juncus<br />

11

ulbosus) or floating bur-reed (Sparganium angustifolim). Floating leaved species such<br />

as bog pondweed (Potamogeton polygonifolius) are restricted to more sheltered areas.<br />

There are few emergent plants, <strong>the</strong> two most conspicuous are <strong>the</strong> blue-green leaves<br />

of bottle sedge (Carex rostrata) and <strong>the</strong> water horsetail (Equisetum fluviatile) with its<br />

distinctive jointed hollow stems. Most of <strong>the</strong>se species, while common in <strong>the</strong> lakes and<br />

<strong>tarns</strong> of Britain’s north west, rarely occur elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

Lower down, oligotrophic <strong>tarns</strong> may support submerged plants such as lesser<br />

marshwort (Apium inundatum), floating club-rush (Eleogiton fluitans) and <strong>the</strong> scarce<br />

aquatic fern pillwort (Pilularia globularia).<br />

3.2. Lowland <strong>tarns</strong><br />

At lower altitudes in central and eastern areas, <strong>the</strong> <strong>tarns</strong> and lakes are often mesotrophic<br />

or eutrophic (nutrient rich), especially in agricultural catchments; where <strong>the</strong>y receive<br />

sewage effluent; or when <strong>the</strong>y occur on limestone. These typically support a more<br />

varied flora including stands of emergents. The plants of upland <strong>tarns</strong> occur, but, in<br />

addition, floating leaved species such as yellow water-lily (Nuphar lutea), white water-lily<br />

(Nymphaea alba) and amphibious bistort (Persicaria amphibia) are found, and stoneworts<br />

- a type of complex alga - can be abundant beneath <strong>the</strong> surface. Pondweeds can be<br />

frequent with a variety of broad and fine-leaved pondweed species, <strong>the</strong> commonest being<br />

broad-leaved pondweed (Potamogeton natans). Submerged narrow-leaved species, such<br />

as small pondweed (Potamogeton berchtoldii) and blunt-leaved pondweed (Potamogeton<br />

obtusifolius) are also found.<br />

White water-lily, our largest floating leaved flower, with conspicous yellow stamens. Frequent in lakes<br />

and <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

12

Lowland <strong>tarns</strong> surrounded by agricultural land tend toward eutrophy and generally<br />

support a diverse flora that includes floating-leaved species such as common waterstarwort<br />

(Callitriche stagnalis) and common duckweed (Lemna minor), and marginal<br />

plants such as floating sweet-grass (Glyceria fluitans), fool’s water-cress (Apium<br />

nodiflorum) and forget-me-nots (Myosotis species). Stands of large, bulky emergent<br />

species such as common reed (Phragmites australis), bulrush (Typha latifolia), branched<br />

bur-reed (Sparganium erectum) and yellow flag (Iris pseudocorus) are typical of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

water bodies. Some display hydrosere development where stands of marginal plants<br />

grade to wet woodland or expanses of mire around <strong>the</strong> perimeter of <strong>the</strong> water body,<br />

blurring <strong>the</strong> boundaries between land and water.<br />

Tarns that have been excessively enriched support large plankton populations and<br />

may be prone to algal blooms. In <strong>the</strong>se conditions, rooted plant communities may be<br />

confined to shallow water due to poor light penetration.<br />

In addition to our native plants, alien species are found in Cumbrian water bodies.<br />

Canadian and Nuttall’s waterweeds (Elodea canadensis and E. nuttallii) have been recorded<br />

since 1874 and 1976 respectively and can out-compete native plants for food and light<br />

and are often abundant in mesotrophic and eutrophic waters. The very invasive New<br />

Zealand pygmyweed (Crassula helmsii), which was absent from <strong>the</strong> Lake District in<br />

Stokoe’s time occurs in some waters, including Windermere and Bassenthwaite, and<br />

has been found in 3 <strong>tarns</strong> during <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong>.<br />

Barngates Tarn was created for water supply and is now used by anglers.<br />

13

4. ARE SMALL WATER BODIES IMPORTANT AND ARE<br />

THEY THREATENED?<br />

Open water is a major feature of Cumbria’s environment, covering nearly 1% of <strong>the</strong><br />

county’s area (Kelly and Parry, 1990). Many <strong>tarns</strong>, ponds and pools are designated as<br />

features on internationally important sites such as <strong>the</strong> Lake District High Fells Special<br />

Area of Conservation (SAC), Subberthwaite, Blawith and Torver Commons SAC, and<br />

North Pennine Moors SAC. Some have been designated as Sites of Special Scientific<br />

Interest (SSSI) in recognition of <strong>the</strong>ir national conservation value and many have been<br />

recognised as being of local wildlife importance through <strong>the</strong> County Wildlife Sites<br />

system.<br />

The importance of freshwaters is recognised in both <strong>the</strong> UK and Cumbria Biodiversity<br />

Action Plans. Mesotrophic water bodies are a priority habitat in both. Oligotrophic<br />

water bodies are a new priority habitat in <strong>the</strong> UK BAP and in Phase 2 of <strong>the</strong> CBAP.<br />

Work over <strong>the</strong> last few years has demonstrated that small water bodies play a key role<br />

in maintaining biodiversity at <strong>the</strong> landscape scale (Williams et al., 2004) and ponds have<br />

recently been added to <strong>the</strong> UK BAP list of priority habitats. Some aquatic species have<br />

been designated as BAP species, including pillwort and great crested newt (Triturus<br />

cristatus).<br />

There are many pressures upon <strong>the</strong> aquatic environment resulting from human<br />

activities such as nutrient enrichment, agricultural runoff, forestry, industrial pollution,<br />

fisheries and recreational pressures. These impacts affect <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> aquatic<br />

environment, although <strong>the</strong> response of any given water body varies, with some being<br />

relatively resistant to change whilst o<strong>the</strong>rs are more sensitive.<br />

Lakes naturally evolve over time, gradually filling with sediment and vegetation,<br />

becoming increasingly shallow, which in turn impacts on <strong>the</strong>ir ecology. Current <strong>the</strong>ory<br />

suggests that most natural waters are initially oligotrophic and naturally become more<br />

nutrient rich with time, though this trend can be very slow in exposed upland <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

The impacts of human activities such as intensive farming and sewage effluent often<br />

accelerate this natural evolution, which are <strong>the</strong>n reflected in changes in <strong>the</strong> biodiversity<br />

of <strong>the</strong> water body. In water bodies that are heavily enriched as a result of human activity,<br />

biodiversity is depressed because planktonic and filamentous algae (blanket-weed)<br />

increase rapidly at <strong>the</strong> expense of o<strong>the</strong>r aquatic species such as many of <strong>the</strong> pondweed<br />

Potamogeton and stonewort Chara species.<br />

Eutrophication is often cited as being one of <strong>the</strong> most important issues currently facing<br />

freshwater bodies. The application of fertilisers and high densities of cows and sheep<br />

are major causes of enrichment of aquatic systems. Nitrate, phosphate, and silt-enriched<br />

waters run off agricultural land into local water bodies, and can impact <strong>the</strong>ir ecology.<br />

Greater levels of nutrients encourage <strong>the</strong> growth of more nutrient demanding, faster<br />

growing plant species, stimulating competition for space and light to <strong>the</strong> detriment of<br />

less robust, slow growing plants adapted to lower nutrient conditions. Erect, canopy<br />

producing aquatic plants increase with increasing sediment fertility, whereas rosette or<br />

bottom-dwelling growth forms decline. A similar trend is shown with increasing water<br />

turbidity, with only <strong>the</strong> more robust species flourishing in highly turbid conditions<br />

14

often associated with eutrophic conditions. In extreme eutrophication situations very<br />

few macrophytes can survive in <strong>the</strong> turbid waters resulting from an explosion of algal<br />

growth, and <strong>the</strong> low oxygen levels which result when blooms die back are toxic to<br />

many aquatic animals, resulting in a general decline in biodiversity. Mesotrophic<br />

waters are particularly vulnerable to increases in nutrient levels.<br />

Climate change is likely to have an effect on <strong>the</strong> chemistry and <strong>the</strong> biology of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>tarns</strong>. Warmer year-round temperatures and corresponding phenological (phenology<br />

is <strong>the</strong> study of periodic plant and aminal life cycle events) change have been widely<br />

reported in <strong>the</strong> UK, hence climatic changes may already be having an impact on aquatic<br />

communities. Changes in temperature and earlier growing seasons will impact <strong>the</strong><br />

biomass and distribution of macrophytes and may encourage survival and growth of<br />

alien species. Impacts from rising temperatures may mimic or exacerbate some of <strong>the</strong><br />

effects of eutrophication, stimulating algal blooms.<br />

On a more local scale, factors such as grazing pressure by waterfowl can have a serious<br />

impact on <strong>the</strong> aquatic flora of a tarn, enrichment around shoreline roosting areas can<br />

account for localised raised nutrient levels. It is suggested that waterfowl can contribute<br />

to loss of reeds around some water bodies. The reduction in stock grazing in Cumbria<br />

following <strong>the</strong> Foot and Mouth outbreak in 2001, may also have had an impact on <strong>the</strong><br />

tarn edge vegetation, as <strong>the</strong> lighter grazing pressure would encourage a greater range<br />

of more palatable species to survive.<br />

Invasion by alien species represents a significant long-term threat to standing waters<br />

because once established <strong>the</strong>ir elimination may prove impossible. Canadian and<br />

Nuttalls waterweed are already firmly established in many of lakes and <strong>tarns</strong>, often<br />

replacing native species such as pondweeds. New Zealand pygmyweed is very<br />

invasive and can rapidly colonise a water body, affecting <strong>the</strong> quality of <strong>the</strong> water<br />

and preventing <strong>the</strong> growth of o<strong>the</strong>r plants. It has already invaded a number of lakes<br />

including Bassenthwaite Lake, Coniston and Derwent Water but so far has spread to<br />

only a few <strong>tarns</strong>. Parrot’s fea<strong>the</strong>r (Myriophyllum aquaticum), ano<strong>the</strong>r aquatic invasive<br />

was found in one pond during <strong>the</strong> survey. These and o<strong>the</strong>r species may benefit from<br />

warmer winters.<br />

1

<strong>5.</strong> THE CUMBRIA TARNS PROJECT<br />

<strong>5.</strong>1. When and why was it set up?<br />

The Cumbria Tarns Project started in 2003 as part of CWT’s Community Action for<br />

Wildlife programme. Freshwater was one of three areas (<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs being marine<br />

and road verges) devised to provide Trust members and o<strong>the</strong>rs with opportunities to<br />

experience and learn about natural environments. The idea for <strong>the</strong> Project arose from a<br />

partnership between CWT and <strong>the</strong> FBA. As a result, <strong>the</strong>y formed a specialist Freshwater<br />

Group, which was made up of organisations and individuals with an interest in <strong>the</strong><br />

freshwater environment including <strong>the</strong> FBA, EN (now NE), <strong>the</strong> EA and <strong>the</strong> CEH.<br />

The <strong>project</strong> had two clear objectives: –<br />

1<br />

1. to resurvey <strong>tarns</strong> that had been surveyed by Ralph Stokoe in <strong>the</strong> late<br />

1970s;<br />

2. to provide volunteers with an opportunity to discover more about<br />

Cumbria’s <strong>tarns</strong>, gaining experience in surveying freshwater habitats<br />

and species.<br />

By re-surveying Stokoe’s work, comparisons could be made between <strong>the</strong> two sets of<br />

data, to examine changes in <strong>the</strong> species composition and tarn ecology over 30 years.<br />

Whilst <strong>the</strong>re have been many studies of <strong>the</strong> larger lakes, <strong>the</strong> smaller <strong>tarns</strong> and ponds<br />

had, in comparison, been neglected. The Tarns Project was <strong>the</strong> largest systematic study<br />

of small water bodies in Cumbria since Ralph Stokoe.<br />

A pilot Tarns Project took place during <strong>the</strong> field season of 2004, to test survey methods<br />

and assess <strong>the</strong> amount of volunteer interest in survey work on plants in <strong>tarns</strong>. It also<br />

enabled CWT and <strong>the</strong> FBA to organise training courses and so help volunteers to gain<br />

confidence in surveying <strong>tarns</strong>. This pilot was popular enabling <strong>the</strong> Project to obtain<br />

funding for a part-time Project officer for <strong>the</strong> 2005 season. The Project officer undertook<br />

survey work and provided support for <strong>the</strong> volunteer survey team, for example, by<br />

arranging permissions from landowners. 2005 turned out to be ano<strong>the</strong>r successful<br />

season, with 20 volunteer surveyors surveying nearly 100 <strong>tarns</strong> and ponds.<br />

Because of <strong>the</strong> popularity and success of <strong>the</strong> Project, CWT made successful proposals<br />

to SITA Environmental Trust and <strong>the</strong> Heritage Lottery Fund to continue <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong><br />

until <strong>the</strong> end of 2008. The bid set out how <strong>the</strong> surveys of meso-oligotrophic <strong>tarns</strong> could<br />

contribute to <strong>the</strong> UKBAP and <strong>the</strong> CBAP, and establish <strong>the</strong> distribution of <strong>the</strong> scarce<br />

aquatic fern pillwort in Cumbria.

<strong>5.</strong>2. Pillwort survey<br />

In 2006, specific surveys for <strong>the</strong> aquatic fern pillwort (Pilulifera globularia) were carried<br />

out. Largely as a result of drainage, pillwort is declining throughout its range in<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn Europe and all remaining sites in NW England are in Cumbria.<br />

Pillwort has been recorded historically for about 30 sites in Cumbria, dating back to <strong>the</strong><br />

nineteenth century, often with scant location details. Using <strong>the</strong>se records and Stokoe’s<br />

data we identified <strong>tarns</strong> that appeared likely to support pillwort.<br />

Pillwort, a nationally scarce aquatic fern.<br />

Tarns in ten 10km squares were surveyed in 2006, and <strong>the</strong> plant was found at eight<br />

sites, and two new sites where it had not previously been recorded. Surveyors made<br />

notes on impacts and management contributing to <strong>the</strong> condition of <strong>the</strong> tarn, such as<br />

disturbance, water level and <strong>the</strong> presence of invasive species, which may affect <strong>the</strong><br />

growth and continued presence of pillwort.<br />

<strong>5.</strong>3. O<strong>the</strong>r surveys<br />

In 2006, some trial fish surveys were undertaken with help from specialists at <strong>the</strong> EA,<br />

<strong>the</strong> CEH and <strong>the</strong> FBA. This proved popular with volunteers and, in 2007, surveys at<br />

six sites were undertaken during <strong>the</strong> summer at which fish lengths and weights were<br />

recorded and scale samples taken for fish age determination.<br />

1

In 2008, <strong>the</strong> Tarns Project was commissioned by <strong>the</strong> EA with additional funding from <strong>the</strong><br />

Lake District National Park (LDNP) to complete a macrophyte survey of Windermere.<br />

This was led by a aquatic macrophyte specialist surveyor, who had started <strong>the</strong> survey<br />

in 2006. Members of <strong>the</strong> tarn<br />

survey team had assisted<br />

during <strong>the</strong> 2006 survey and<br />

were involved again in 2008.<br />

The survey was carried out<br />

from a small boat that moved<br />

in and out from <strong>the</strong> shore<br />

along transects. A bathyscope<br />

(a glass bottomed viewing<br />

bucket) was used to record<br />

<strong>the</strong> submerged aquatic flora<br />

as <strong>the</strong> boat moved along each<br />

transect. The primary purpose<br />

of <strong>the</strong> survey was to identify<br />

areas of high conservation<br />

value indicated by species rich<br />

assemblages or <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

of scarce species such as<br />

six-stammened waterwort<br />

(Elatine hexandra), which will<br />

help inform <strong>the</strong> EA and <strong>the</strong><br />

LDNP in <strong>the</strong>ir conservation<br />

work on Windermere.<br />

<strong>5.</strong>4. Raising awareness<br />

CWT and FBA have promoted <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> through talks and presentations throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> county and press coverage including BBC’s Countryfile. In association with <strong>the</strong><br />

Friends of <strong>the</strong> Lake District (FLD), CWT ran a successful Festival of <strong>the</strong> Tarns for two<br />

weeks in 2006 to raise awareness of <strong>the</strong> habitat. This involved guided walks, a series of<br />

evening talks and ‘taster’ days for <strong>the</strong> public to look at <strong>tarns</strong> and pools.<br />

A book, ‘Tarns of <strong>the</strong> Fells’, compiled by a team led by FLD, but involving CWT and<br />

FBA was published in 2005, which toge<strong>the</strong>r with a website, www.<strong>tarns</strong>of<strong>the</strong>fells.org.uk,<br />

raised <strong>the</strong> profile and public awareness of <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

1<br />

Six-stammened waterwort, an inconspicuous plant found on<br />

mud, sand or gravel in shallow water. The Lake District is a<br />

stronghold for this nationally scarce plant.

6. VOLUNTEERS<br />

The Project was initially conceived as a volunteer-based survey, with <strong>the</strong> aim of<br />

engaging local people in surveying and experiencing freshwater habitats. We have<br />

been lucky enough to have engaged a team of around 30 people who have contributed<br />

to <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong>. Some of <strong>the</strong>se have surveyed just one or two <strong>tarns</strong>, but <strong>the</strong> core team of<br />

about 12 people regularly survey many more than this.<br />

These people come from all walks of life. Some are Wildlife Trust members and staff<br />

who wanted to find out more about freshwater life. O<strong>the</strong>rs work professionally in <strong>the</strong><br />

freshwater field and wanted to get involved in <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong>. We also have graduates<br />

and MSc students who want to improve and use <strong>the</strong>ir field skills and get experience of<br />

surveying, and local naturalists who are generally interested in <strong>the</strong> natural world and<br />

undertake recording in <strong>the</strong> County.<br />

Training day at Loughrigg Tarn.<br />

6.1. The importance of volunteers to <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong><br />

The Tarns Project would not have been possible without <strong>the</strong> participation of <strong>the</strong> survey<br />

team of dedicated and enthusiastic volunteers. The volunteer survey team conducted<br />

nearly 400 surveys of some 370 <strong>tarns</strong>. Volunteers also contributed by contacting<br />

landowners, and inputting survey data. The volunteers were highly motivated, often<br />

had local knowledge of <strong>the</strong> area <strong>the</strong>y were surveying and in some cases had contacts<br />

with local landowners. The contribution of volunteers was integral to <strong>the</strong> Project.<br />

1

6.2. Training volunteers<br />

Most of <strong>the</strong> volunteers were keen botanists, some with experience of working on local<br />

floras or o<strong>the</strong>r recording <strong>project</strong>s. However, specialist training in <strong>the</strong> survey of aquatic<br />

macrophtyes, including survey methodology and <strong>the</strong> identification of difficult aquatic<br />

plant groups, was needed. This was vital to ensure survey standardisation, recording<br />

data that enabled comparisons with Stokoe’s results and with future surveys.<br />

The Pilot survey in 2004 helped to identify <strong>the</strong> knowledge and skills requirement<br />

for <strong>the</strong> survey and ensure that volunteers were <strong>the</strong>n provided with all <strong>the</strong> necessary<br />

information on survey methodology, identification skills, equipment and training.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early stages of <strong>the</strong> Project training courses were offered to increase survey and<br />

plant identification skills and to build confidence in identification of <strong>the</strong> more difficult<br />

plant groups. Training courses also provided a chance for meeting o<strong>the</strong>r members of<br />

<strong>the</strong> survey team.<br />

6.3. The role of <strong>the</strong> Project officer<br />

CWT, <strong>the</strong> FBA and <strong>the</strong> Volunteer Co-ordinator for <strong>the</strong> Community Action for Wildlife<br />

Project provided <strong>the</strong> necessary support and coordination in <strong>the</strong> initial stages of <strong>the</strong><br />

Project. In 2005, a Tarns Project officer was appointed whose duties have included;<br />

20<br />

• Providing a contact at <strong>the</strong> Wildlife Trust.<br />

• Providing support to <strong>the</strong> volunteer survey team.<br />

• Training volunteer surveyors.<br />

• Arranging access with landowners.<br />

• Providing maps for surveyors.<br />

• Co-ordinating identification and verification of plant specimens.<br />

• Liaising with Plantlife, LDNP, EA and consultants for specialist surveys.<br />

Project officers have also provided regular feedback to <strong>the</strong> survey team, with updates<br />

on Project progress and how <strong>the</strong> information <strong>the</strong>y had collected was being used.

7. TARNS SURVEY METHOD<br />

7.1. Introduction<br />

It was important that <strong>the</strong> information collected for each site was comprehensive,<br />

accurate and standardised. A standard survey method was <strong>the</strong>refore used to ensure<br />

consistency between different surveyors and allow valid comparison to be made<br />

between sites and over time. This was achieved through training and, in <strong>the</strong> early<br />

days of <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong>, less experienced volunteers being mentored by more experienced<br />

surveyors. In 2005, a Project handbook was produced that described <strong>the</strong> survey<br />

methodology and <strong>the</strong> surveyors’ role in <strong>the</strong> Project.<br />

7.2. Survey method<br />

A standard method for surveying aquatic macrophytes was developed by <strong>the</strong> former<br />

Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) and by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) for <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

extensive survey of freshwater lochs in <strong>the</strong> 1980’s and 1990’s. The method entailed<br />

walking <strong>the</strong> perimeter of <strong>the</strong> water body to record shoreline and shallow water<br />

vegetation. Deeper water was sampled by means of a grapnel thrown in from <strong>the</strong> bank<br />

at intervals. The cover of all plants was recorded using <strong>the</strong> DAFOR scale (Dominant,<br />

Abundant, Frequent, Occasional, Rare). The main stands of vegetation were mapped<br />

and target notes were written to give a record of <strong>the</strong> vegetation, environmental data and<br />

any o<strong>the</strong>r useful information. Photographs of <strong>the</strong> tarn, and any notable or interesting<br />

plant or animal species seen were taken.<br />

Permission of <strong>the</strong> landowner was obtained before visiting every tarn. Prior to survey,<br />

surveyors would generally read any existing information about <strong>the</strong> water body,<br />

familiarising <strong>the</strong>mselves with species and features that have been previously recorded.<br />

Most of <strong>the</strong> surveys were carried out between June and October, usually by groups<br />

of two or more surveyors, all of whom had received training and were competent<br />

botanists.<br />

For <strong>the</strong> purposes of <strong>the</strong> Project we defined a pond or tarn as a water body that contains<br />

water for at least four months of <strong>the</strong> year. For practical reasons we did not survey <strong>the</strong><br />

larger lakes in Cumbria, except for Ennerdale Water and part of Windermere; aside<br />

from this no upper or lower limits to <strong>the</strong> size of a water body were set. The water<br />

bodies surveyed have mainly been <strong>tarns</strong>, but have also included reservoirs and small<br />

pools.<br />

21

The principal aims of <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> was to repeat <strong>the</strong> botanical surveys carried out by<br />

Ralph Stokoe, <strong>the</strong>refore at a minimum it was necessary to record all aquatic plant<br />

species at each tarn. The range of information recorded was however wider than that<br />

collected by Stokoe and included;<br />

22<br />

• A record of all plant species, and <strong>the</strong>ir abundance.<br />

• A detailed map of vegetation stands showing <strong>the</strong> extent of marginal,<br />

emergent and aquatic plant species with dominant species codes.<br />

• A completed survey form recording environmental data such as water<br />

clarity and substrate, any management and impacts, and adjacent<br />

habitats.<br />

• Biodiversity Action Plan species.<br />

• Information needed for <strong>the</strong> assessment County Wildlife Site status.<br />

• Written description of <strong>the</strong> tarn.<br />

Fish surveyor setting a fyke net at Blea Water.

8. TARN SURVEY RESULTS<br />

8.1. Key achievements<br />

• 390 macrophyte surveys of 370 water bodies.<br />

• The formation of a team of trained tarn surveyors.<br />

• Assisting with <strong>the</strong> completion of a successful MSc <strong>the</strong>sis using<br />

comparative data to highlight changes in plant communities over 30<br />

years.<br />

• A completed Pillwort survey confirming <strong>the</strong> species at 8 sites and<br />

adding 2 new sites.<br />

• Trial fish surveys completed.<br />

8.2. Data analysis<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> principal objectives of <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> was to repeat surveys of <strong>tarns</strong> that had<br />

been surveyed by Ralph Stokoe in <strong>the</strong> late 1970’s. This has provided us with a dataset<br />

of tarn data that can be used in comparative analysis.<br />

A first stage analysis of <strong>the</strong> data, has been carried out by Tamsin Douglas, an MSc<br />

student at <strong>the</strong> University of Birmingham (Douglas, 2007). The study analysed records<br />

from Stokoe’s surveys and selected records from <strong>the</strong> first 3 years of <strong>the</strong> Cumbria Tarns<br />

Project (2004-06) in an attempt to assess whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> botanical quality of <strong>tarns</strong> within<br />

<strong>the</strong> Lake District National Park has changed, and to determine <strong>the</strong> nature of any such<br />

changes. PLEX scores (Duigan et al., 2006) and Ellenberg values for moisture, pH<br />

and fertility (Hill et al., 1999) inferred from tarn species lists were instrumental in<br />

this analysis. Tarns were also classified into ecotype groups based on <strong>the</strong>ir botanical<br />

composition, following <strong>the</strong> key in Duigan et al. (2006).<br />

A dataset of 93 <strong>tarns</strong> was sub-divided into ‘upland type’ and ‘lowland type’ <strong>tarns</strong> as it<br />

was anticipated that any change in <strong>the</strong> trophic status of <strong>tarns</strong> would be more evident<br />

in <strong>the</strong> lowland sub-group due to proximity to direct sources of nutrients, such as<br />

agricultural runoff.<br />

The study compared several aspects of <strong>the</strong> data from <strong>the</strong> two survey periods,<br />

including:-<br />

• Changes in distribution of individual species within <strong>the</strong> study area.<br />

• Community structure (in terms of growth form of constituent plants),<br />

particular among rosette forming species.<br />

• Species richness of each tarn (both in terms of all macrophytes, and of<br />

‘true aquatics’).<br />

• Ellenberg scores for each tarn, for fertility, pH and moisture (Hill et al.,<br />

1999).<br />

• Ecotype scores for each tarn based PLEX values for floating and<br />

submerged species only, following Duigan et al. (2006).<br />

23

8.3. Results and conclusions of first analysis<br />

The results summarised in this report should be regarded as interim – and it is intended<br />

that <strong>the</strong> full data set should be subjected to fur<strong>the</strong>r analysis as <strong>the</strong> next stage of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>project</strong>. The results of <strong>the</strong> Douglas analysis are presented below:<br />

The most distinctive trend in <strong>the</strong> data is <strong>the</strong> decline in species richness, particularly<br />

among <strong>the</strong> submerged and floating macrophyte species.<br />

The average number of aquatic plant species recorded from each tarn has changed,<br />

falling from 12.08 in <strong>the</strong> late 1970’s to 11.11 in <strong>the</strong> 2004-06 data. The average number of<br />

‘true aquatics’ has fallen from 7.63 per tarn in Stokoe’s data to 6.7 in <strong>the</strong> recent surveys,<br />

being on average almost one less aquatic plant in every tarn surveyed.<br />

This change was most apparent in <strong>the</strong> upland group of <strong>tarns</strong> where species richness overall<br />

declined from 65 species to 54 species, including 7 new species and 18 not re-recorded in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2004-06 surveys. A smaller decline was observed in <strong>the</strong> lowland <strong>tarns</strong> where species<br />

richness decreased from 76 species to 71 species (of which 8 species were newly recorded<br />

and 13 not re-recorded in <strong>the</strong> 2004-06 surveys). Most species not re-recorded were locally<br />

uncommon, having been recorded by Stokoe in only one or two <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

There have been changes in community composition with declines in floating leaved<br />

and submerged species, particularly <strong>the</strong> rossete-forming species such as quillwort.<br />

Conversely, <strong>the</strong>re has been a notable increase in <strong>the</strong> number of emergent species and<br />

slight increases in free-floating plants and charophytes.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> lowland sub-group <strong>the</strong>re was a shift in nutrient status towards more eutrophic<br />

conditions. In <strong>the</strong> upland sub-group, however, <strong>the</strong>re was no detected change in nutrient<br />

status.<br />

There have been apparent changes in <strong>the</strong> distribution of several species since Stokoe’s<br />

survey. In lowland <strong>tarns</strong>, species often associated with mesotrophic waters, such as<br />

Potamogeton obtusifolius, P. berchtoldii and Elodea spp, have almost doubled in range.<br />

Quillwort, a species with a strong nor<strong>the</strong>rn distribution in <strong>the</strong> U.K. and characteristic<br />

of oligotrophic waters, has declined substantially across <strong>the</strong> study area (upland and<br />

lowland <strong>tarns</strong>) from 29 to 17 <strong>tarns</strong>. Lythrum portula, a plant generally encountered in<br />

draw-down zones particularly of mesotrophic waters has also declined significantly, as<br />

has Ranunculus peltata and Callitriche spp, pioneer species of bare mud and occasionally<br />

inundated ground.<br />

In lowland <strong>tarns</strong>, introduced (alien) species have also increased substantially, though<br />

<strong>the</strong>y still only account for a small percentage of <strong>the</strong> total species present.<br />

24

Species with a sou<strong>the</strong>rn distribution (which includes all 3 non-native species<br />

encountered in <strong>the</strong>se surveys) in <strong>the</strong> UK have increased across <strong>the</strong> dataset, and species<br />

with a typically nor<strong>the</strong>rn distribution in <strong>the</strong> UK have decreased substantially. When<br />

<strong>the</strong>se records are split into upland and lowland groups, <strong>the</strong> trend for lowland <strong>tarns</strong><br />

matches <strong>the</strong> pattern seen above. In upland <strong>tarns</strong>, however, both nor<strong>the</strong>rn and sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

groups of species are in decline.<br />

The observed decline in species richness may be slightly exaggerated in <strong>the</strong> analysis as<br />

a consequence of survey frequency. Stokoe carried out his surveys at different times of<br />

<strong>the</strong> year and often visited sites more than once, resulting in some <strong>tarns</strong> having a species<br />

list collated from 2 or more surveys. The 2004-06 surveys, with two exceptions, involved<br />

only one site visit and as such provided just a snapshot of <strong>the</strong> flora at that time. These<br />

two factors would imply some level of bias towards greater species richness in Stokoe’s<br />

dataset, though it is worth noting that surveys carried out as part of <strong>the</strong> Cumbria Tarns<br />

Project involved two, or frequently several, individuals <strong>the</strong>reby reducing <strong>the</strong> chance of<br />

missing any species.<br />

Quillwort, a rosette forming species characteristic of oligotrophic <strong>tarns</strong>.<br />

2

9. THE FUTURE<br />

9.1. How will <strong>the</strong> information be used?<br />

The Tarns Project has collected data for 370 <strong>tarns</strong>, including many that have not<br />

been previously studied in detail, adding to <strong>the</strong> knowledge of <strong>the</strong> distribution of<br />

aquatic plant species, including some rarer species such as awlwort and pillwort.<br />

The survey data has expanded <strong>the</strong> level of scientific information available to officers<br />

from conservation organisations and can be used to protect <strong>the</strong>m fur<strong>the</strong>r, through<br />

management, designation and planning.<br />

The species data collected by <strong>the</strong> Project, toge<strong>the</strong>r with data from previous surveys<br />

has been entered onto <strong>the</strong> new Tarns and Ponds database designed by Tony Marshall,<br />

and is available through <strong>the</strong> Tarns of <strong>the</strong> Fells website, www.<strong>tarns</strong>of<strong>the</strong>fells.org.uk.<br />

Conservation bodies and o<strong>the</strong>rs can search <strong>the</strong> database for information on specific<br />

ponds and <strong>tarns</strong> or species of interest.<br />

Copies of our survey reports have been sent to landowners including <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Trust, United Utilities, <strong>the</strong> LDNP, and many private landowners. The survey results<br />

will help assess whe<strong>the</strong>r existing management regimes are appropriate.<br />

9.2. Future management<br />

It is hoped that <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong> survey will help to inform any decisions made about<br />

<strong>the</strong> management of Cumbria’s <strong>tarns</strong> and how best to protect <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> future. Results<br />

can also be used to inform catchment-wide strategies to protect and enhance upland<br />

environments.<br />

Aquatic macrophytes in <strong>tarns</strong> are indicators of <strong>the</strong> health not only of <strong>the</strong> waters<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves but also of <strong>the</strong>ir surrounding environment. The health of a freshwater body<br />

is directly related to <strong>the</strong> state of its catchment and this forms <strong>the</strong> basis for European<br />

legislation to protect freshwater systems, <strong>the</strong> Water Framework Directive (Directive<br />

2000/60/EC).<br />

The information is useful for <strong>the</strong> decision-making bodies such as <strong>the</strong> EA, NE and <strong>the</strong><br />

LDNP. They may use it, for example to monitor change, particularly on designated<br />

sites, or deciding whe<strong>the</strong>r to issue consents and planning permissions.<br />

The data is also useful for organisations carrying out research on freshwaters such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> FBA and <strong>the</strong> CEH.<br />

CWT is regularly consulted about planning applications for works proposed throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> county. Tarn data collected is already being used by CWT officers and o<strong>the</strong>rs to<br />

advise landowners, developers and planners if a proposed development would impact<br />

a site. If <strong>the</strong> work proposed is potentially detrimental, we can help to ensure that <strong>the</strong><br />

water body is protected.<br />

2

Data collected by <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> has been used to develop robust guidelines for <strong>the</strong><br />

selection of new County Wildlife Sites in Cumbria. These guidelines have been used<br />

to assess <strong>tarns</strong> surveyed by <strong>the</strong> Project, with 19 tarn new sites selected as County<br />

Wildlife Sites. County Wildlife Sites are <strong>the</strong> most important places for wildlife outside<br />

legally protected land such as SSSIs or SACs. The sites in Cumbria are part of a series<br />

across Britain. The designation of <strong>the</strong>se sites complements <strong>the</strong> protection afforded by<br />

statutory sites, primarily by identifying areas that have substantive wildlife interest<br />

and <strong>the</strong>refore merit some form of protection, primarily through <strong>the</strong> planning system.<br />

Data collected from our surveys has contributed to <strong>the</strong> national ponds database held<br />

by Pond Conservation – a charity devoted to <strong>the</strong> survey, restoration and monitoring<br />

of small water bodies. The results of <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> have contributed to meeting both UK<br />

and CBAP habitat (oligotrophic and mesotrophic standing waters) and species targets<br />

including pillwort.<br />

There is an increased degree of concern about invasive alien plants in water and <strong>the</strong><br />

records resulting from <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> have already contributed to <strong>the</strong> county’s knowledge<br />

of <strong>the</strong> spread of invasive species and some advice has been given to tarn owners on<br />

management and <strong>the</strong> need to control/remove <strong>the</strong>se species.<br />

It is hoped that <strong>the</strong> work of <strong>the</strong> Tarns Project will continue in <strong>the</strong> future. There is scope<br />

for fur<strong>the</strong>r analysis of <strong>the</strong> macrophyte data collected by <strong>the</strong> Project, particularly <strong>the</strong> data<br />

collected during 2007 and 2008 seasons. This is now planned for March and April 2009.<br />

There is a core of volunteers keen to survey <strong>tarns</strong> and <strong>the</strong> FBA and CWT are looking<br />

at ways of continuing to support <strong>the</strong>m. We are currently exploring opportunities for<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r work on <strong>tarns</strong>, which might include; i) addressing particular aspects of <strong>the</strong><br />

aquatic plants, ii) extending <strong>the</strong> <strong>project</strong> into surveys of fish species (possibly paying<br />

particular attention to BAP species) or iii) extending <strong>the</strong> work into surveys of particular<br />

invertebrates - again possibly BAP species. O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>project</strong>s may involve using <strong>the</strong> data<br />

to improve <strong>the</strong> management of <strong>tarns</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir catchments.<br />

2

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

The Tarns Project has formed links and worked with a variety of organisations including<br />

Natural England, The National Trust, <strong>the</strong> Lake District National Park, <strong>the</strong> Environment<br />

Agency, United Utilities, Forestry Commission and Plantlife.<br />

Specialist training in aquatic plant identification was provided by a number of local<br />

and national experts including <strong>the</strong> BSBI county recorder who also accepted our plant<br />

specimens for verification. Staff at <strong>the</strong> FBA, CEH, and <strong>the</strong> EA also supported <strong>the</strong><br />

Project.<br />

The Project has been sponsored by a number of funding bodies, principally by <strong>the</strong><br />

Heritage Lottery Fund and SITA UK. SITA allocates funding through <strong>the</strong> Landfill<br />

Communities Fund for community life and wildlife <strong>project</strong>s, which help to achieve<br />

<strong>the</strong> UK’s Biodiversity Action Plan. Funding has also been provided by <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Trust, Lake District National Park, The Environment Agency, Natural England and <strong>the</strong><br />

Joseph and Nancy Burton Charitable Trust.<br />

We are very grateful to <strong>the</strong> many landowners who have allowed us access to <strong>the</strong>ir land<br />

to carry out <strong>the</strong> surveys. They have included large owners such as <strong>the</strong> National Trust,<br />

Forestry Commission, United Utilities, <strong>the</strong> Lake District National Park, many private<br />

estates and a myriad of small landowners.<br />

Finally, we must mention again <strong>the</strong> vital role that <strong>the</strong> volunteer surveyors have played<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Project. Without <strong>the</strong>ir enthusiasm and dedication <strong>the</strong> Project could not have<br />

achieved what it has and <strong>the</strong>y have demonstrated again <strong>the</strong> important role that<br />

volunteers play in conservation and set a model for future <strong>project</strong>s.<br />

Map showing distribution of lakes and <strong>tarns</strong> in Cumbria.<br />

2

11. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING<br />

Charter, E. (1984). A Survey, classification and evaluation of small open waters in<br />

Cumbria. London: University College. MSc Dissertation.<br />

Douglas, T. (2007). Detecting changes in <strong>the</strong> aquatic flora of <strong>the</strong> <strong>tarns</strong> of Cumbria’s<br />

Lake District. University of Birmingham. MSc Dissertation.<br />

Halliday, G. (1997). A Flora of Cumbria. University of Lancaster, Centre for North-West<br />

Regional Studies.<br />

Halliday, G. (1999). Cumbria’s Aquatic Plants. Cumbrian Wildlife. No.53.<br />

Haworth, E., de Boer, G., Evans, I., Osmaston, H., Pennington, W., Smith, A., Storey, P.<br />

& Ware, W. (2003). Tarns of <strong>the</strong> central Lake District. Ambleside: Brathay Exploration<br />

Group Trust.<br />

Kelly, P.G. and Perry, K.A. (1990). Wildlife habitat in Cumbria. Research and Survey in<br />

Nature Conservation No. 30. Peterborough: Nature Conservancy Council.<br />

Palmer, M. (1992). A Botanical classification of standing waters in Great Britain.<br />

Peterborough: Nature Conservancy Council. Research and Survey in Nature<br />

Conservation, No. 19.<br />

Preston, C.D. and Croft, J.M. (1997). Aquatic plants in Britain and Ireland. Colchester:<br />

Harley Books.<br />

Ratcliffe, D. (2002). Lakeland, The Wildlife of Cumbria. The New Naturalist. Harper<br />

Collins.<br />

Rodwell, J. Ed. (1991). British Plant Communities. Volume 2, Mires and heaths.<br />

Cambridge University Press.<br />

Stokoe, R. (1983). Aquatic macrophytes in <strong>the</strong> <strong>tarns</strong> and lakes of Cumbria. FBA<br />

Occasional Publication No 18. Ambleside: FBA.<br />

Williams P., Whitfield M., Biggs J., Bray S., Fox G., Nicholet P., and Sear D. (2004).<br />

Comparative biodiversity of rivers, streams, ditches and ponds in an agricultural<br />

landscape in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn England. Biological Conservation 115, 329-341.<br />

2

The Cumbria Tarns Project has been made possible through <strong>the</strong> generous<br />

donations of both money and time from <strong>the</strong> following organisations: