STUDENT SCRIPT - Englisches Seminar II - Universität zu Köln

STUDENT SCRIPT - Englisches Seminar II - Universität zu Köln

STUDENT SCRIPT - Englisches Seminar II - Universität zu Köln

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

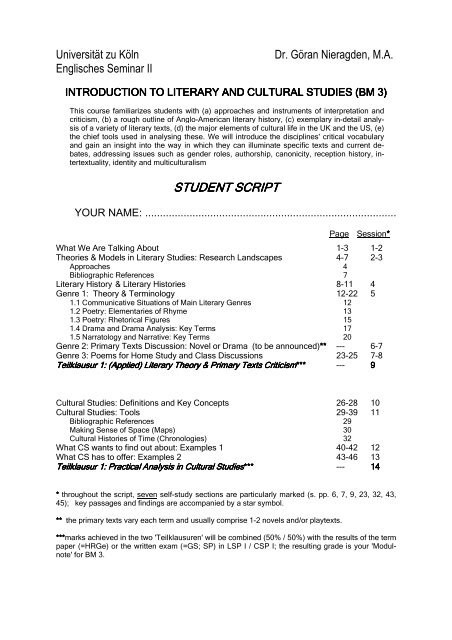

<strong>Universität</strong> <strong>zu</strong> <strong>Köln</strong> Dr. Göran Nieragden, M.A.<br />

<strong>Englisches</strong> <strong>Seminar</strong> <strong>II</strong><br />

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION TO TO LITERARY LITERARY AND CULTURAL STUDIES STUDIES ( (BM ( BM 3)<br />

This course familiarizes students with (a) approaches and instruments of interpretation and<br />

criticism, (b) a rough outline of Anglo-American literary history, (c) exemplary in-detail analysis<br />

of a variety of literary texts, (d) the major elements of cultural life in the UK and the US, (e)<br />

the chief tools used in analysing these. We will introduce the disciplines' critical vocabulary<br />

and gain an insight into the way in which they can illuminate specific texts and current debates,<br />

addressing issues such as gender roles, authorship, canonicity, reception history, intertextuality,<br />

identity and multiculturalism<br />

<strong>STUDENT</strong> <strong>STUDENT</strong> <strong>STUDENT</strong> <strong>STUDENT</strong> <strong>SCRIPT</strong> <strong>SCRIPT</strong> <strong>SCRIPT</strong> <strong>SCRIPT</strong><br />

YOUR NAME: .....................................................................................<br />

Page Session*<br />

What We Are Talking About 1-3 1-2<br />

Theories & Models in Literary Studies: Research Landscapes 4-7 2-3<br />

Approaches 4<br />

Bibliographic References 7<br />

Literary History & Literary Histories 8-11 4<br />

Genre 1: Theory & Terminology 12-22 5<br />

1.1 Communicative Situations of Main Literary Genres 12<br />

1.2 Poetry: Elementaries of Rhyme 13<br />

1.3 Poetry: Rhetorical Figures 15<br />

1.4 Drama and Drama Analysis: Key Terms 17<br />

1.5 Narratology and Narrative: Key Terms 20<br />

Genre 2: Primary Texts Discussion: Novel or Drama (to be announced)** --- 6-7<br />

Genre 3: Poems for Home Study and Class Discussions 23-25 7-8<br />

Teilklausur Teilklausur Teilklausur Teilklausur 1: 1: 1: 1: (Applied) (Applied) (Applied) (Applied) Literary Literary Literary Literary Theory Theory Theory Theory & & & & Primary Primary Primary Primary TTexts<br />

TT<br />

exts exts exts Criticism***<br />

Criticism Criticism Criticism***<br />

*** --- 9<br />

Cultural Studies: Definitions and Key Concepts 26-28 10<br />

Cultural Studies: Tools 29-39 11<br />

Bibliographic References 29<br />

Making Sense of Space (Maps) 30<br />

Cultural Histories of Time (Chronologies) 32<br />

What CS wants to find out about: Examples 1 40-42 12<br />

What CS has to offer: Examples 2 43-46 13<br />

Teilklausur Teilklausur Teilklausur Teilklausur 1: 1: 1: 1: Practical Practical Practical Practical Analysis Analysis Analysis Analysis in in in in CCultural<br />

CC<br />

ultural ultural ultural SSSStudies tudies*** tudies tudies *** --- 14<br />

* throughout the script, seven self-study sections are particularly marked (s. pp. 6, 7, 9, 23, 32, 43,<br />

45); key passages and findings are accompanied by a star symbol.<br />

** the primary texts vary each term and usually comprise 1-2 novels and/or playtexts.<br />

***marks achieved in the two 'Teilklausuren' will be combined (50% / 50%) with the results of the term<br />

paper (=HRGe) or the written exam (=GS; SP) in LSP I / CSP I; the resulting grade is your 'Modulnote'<br />

for BM 3.

What What We We Are Are Talking Talking About<br />

About<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 1<br />

WHAT WILL YOU GAIN FROM DOING LITERARY STUDIES? YOUR THOUGHTS:<br />

(a) Elaine Showalter. 2003. Teaching Literature. Oxford: Blackwell, pp.26-27:<br />

[...] when we teach reading literature as a craft, rather than as a body of isolated information,<br />

we want students to learn the following competencies and skills:<br />

1 How to recognize subtle and complex differences in language use.<br />

2 How to read figurative language and distinguish between literal and metaphorical meaning.<br />

3 How to seek out further knowledge about the literary work, its author, its content, or its<br />

interpretation.<br />

4 How to detect the cultural assumptions underlying writings from a different time or society,<br />

and in the process to become aware of one's own cultural assumptions.<br />

5 How to relate apparently disparate works to one another, and to synthesize ideas that<br />

connect them into a tradition or a literary period.<br />

6 How to use literary models as cultural references, either to communicate with others or<br />

to clarify one's own ideas.<br />

7 How to think creatively about problems by using literature as a broadening of one's own<br />

experience and practical knowledge.<br />

8 How to read closely, with attention to detailed use of diction, syntax, metaphor, and<br />

style, not only in high literary works, but in decoding the stream of language everyone in modern<br />

society is exposed to.<br />

9 How to create literary texts of one's own, whether imaginative or critical.<br />

10 How to think creatively within and beyond literary studies, making some connections<br />

between the literary work and one's own life.<br />

11 How to work and learn with others, taking literature as a focus for discussion and analysis.<br />

12 How to defend a critical judgment against the informed opinions of others.<br />

WHAT IS LITERATURE? [all highlighted highlighted passages by me, G.N.]<br />

(a) Jonathan Culler. 1997. Literary Theory. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP, p. 41:<br />

Literature is a paradoxical institution because to create literature is to write according to existing<br />

formulas - to produce something that looks like a sonnet or that follows the conventions<br />

of the novel - but it is also to flout those conventions, to go beyond them. Literature is is<br />

an an institution that lives by expos exposing expos<br />

ing and criticizing its its own own limits limits, limits by testing what will happen if<br />

one writes differently. So literature is at the same time the name for the utterly conventional -<br />

moon rhymes with June and swoon, maidens are fair, knights are bold - and for the utterly<br />

disruptive, where readers have to struggle to create any meaning at all [...].<br />

(b) Ronald Carter. 1997. Investigating English Discourse. Language, Literacy and Literature.<br />

London: Routledge, p. 169:<br />

Literary uses of language and the necessary skills for its interpretation go routinely with all<br />

kinds of text, spoken and written. Literature exists at many different levels for different people<br />

in different communities but it is argued here that literary language is not simply any use of<br />

language. The The main main argument argument [...] [...] is is that that literary literary language language will will always always be be patterned pat<br />

pat terned in some<br />

way way and and will will involve involve a a creative creative play play with with these these patterns. patterns. The patterns may also involve words<br />

or structures which are representational and not intended to be read literally. The patterns<br />

invite involvement on the part of a reader or hearer who then has an option to interpret the<br />

text as the context and circumstances of the language use appear to him/her to demand.<br />

This patterned, representational 'literary' aspect of language is central to language use,<br />

though it will of course occur wih greater density in some texts than others. The sooner language<br />

learners can come to appreciate this central component of language, the sooner they<br />

appreciate that th they th<br />

ey themselves themselves and and other other users users of of language language are are essentially essentially creative.<br />

creative.<br />

(c) Rita Felski. 2008. Uses of Literature. Oxford: Blackwell, p.14:<br />

[...] I propose that reading involves a logic of recognition; recognition recognition recognition that aesthetic experience has analogies<br />

with enchantment<br />

enchantment enchantment<br />

enchantment in a supposedly disenchanted age; that literature creates distinctive<br />

configurations of social knowledge; knowledge knowledge knowledge that we may value the experience of being shocked shocked shocked shocked by<br />

what we read. These four categiories epitomize what I call modes of textual engament: they<br />

are neither intrinsic literary properties nor independent psychological states, but denote<br />

multi-leveled interactions between texts and readers that are irreducible to their separate<br />

parts.

Nieragden: ILCS 2<br />

WHAT ARE LITERARY STUDIES' ? YOUR THOUGHTS:<br />

(a) Philip Hobsbaum. 1970. A Theory of Communication. London: Macmillan, p. 82:<br />

Most misreadings of valuable works are failures of criteria. [...] The critic has a duty to make<br />

the work seem as good as it can: this is not a matter of reading in his own attitudes but finding<br />

out those that are there in the work. The process is one [...] of choosing a criterion: of let let- let<br />

ting ting one’s one’s mind mind explore explore the the the work work from from different different angles angles in in the the hope hope of of finding finding a a viable viable ap ap-<br />

ap<br />

proach proach - of finding, one hopes, the most viable approach. [...] It will not blind us to the faults<br />

of a given work; it may, however, put them in perspective.<br />

(b) Helen Vendler. 1988. The Music of What Happens: Poems, Poets, Critics. Cambridge,<br />

MA: Harvard UP, p. 2:<br />

The aim of a properly aesthetic criticism [...] is not primarily to reveal the meaning of an art<br />

work or disclose (or argue for or against) the ideological values of an art work. The aim of an<br />

aesthetic criticism is to to describe describe describe describe the the art art work work in in such such a a way way that that it it cannot cannot be be confused confused with<br />

with<br />

any any other other art art work work (not an easy task), and to infer from the art work the aesthetic that might<br />

generate this unique configuration.<br />

(c) Peter Washington. 1989. Fraud: Literary Theory and the End of English. London:<br />

Fontana, p. 15:<br />

Academic discourse is concerned less with finding answers than with formulating questions. .<br />

It It teaches teaches us us not not what what to to know know know but but how how to to think.<br />

think.<br />

(d) Harald Fricke & Rüdiger Zymner. 1991. Einübung in die Literaturwissenschaft.<br />

Parodieren geht über Studieren. Paderborn: Schöningh, S. 17:<br />

Die zwei größten Fehler einer literaturwissenschaftlichen Ausbildung (komplementär, aber<br />

leider durchaus kompatibel) wären es deshalb: einerseits den Beteiligten die spontane<br />

Freude am Umgang mit Literatur <strong>zu</strong> nehmen - und sie andererseits vor dieser Literatur begriffslos<br />

mit offenem Munde stehen <strong>zu</strong> lassen.<br />

(e) Barbara Korte, Klaus Peter Müller & Josef Schmied. 1997. Einführung in die Anglistik.<br />

Stuttgart: Metzler, S. 73-74:<br />

Der wissenschaftliche Umgang mit Literatur setzt sich, wie jede wissenschaftliche Betätigung,<br />

bestimmte Erkenntnisziele und nähert sich diesen unter Rückgriff auf Erkenntnismethoden<br />

und möglichst klare Analysebegriffe, also unter Benut<strong>zu</strong>ng einer Fachsprache, die es<br />

<strong>zu</strong> beherrschen gilt. . Ein Ein wichtiges wichtiges Ziel Ziel literaturwissenschaftlichen literaturwissenschaftlichen Arbeitens Arbeitens ist ist es, es, das das Be-<br />

Be<br />

deutungsangebot eutungsangebot eines eines eines Textes Textes möglichst möglichst umfassend umfassend umfassend aus<strong>zu</strong>schöpfen aus<strong>zu</strong>schöpfen und die gewonnenen<br />

Erkenntnisse Erkenntnisse präzise präzise und und für für andere andere nachvollziehbar nachvollziehbar <strong>zu</strong> <strong>zu</strong> formulieren. formulieren.<br />

Die Resultate einer<br />

wissenschaftlichen Auseinanderset<strong>zu</strong>ng mit Literatur müssen kommunizierbar und überprüfbar<br />

sein, auch wenn das Verstehen literarischer Texte als typisch geisteswissenschaftliches<br />

Verfahren [...] nie so objektiv sein kann wie Erkenntnisse in den Naturwissenschaften. Um so<br />

wichtiger ist es, das eigene Verständnis eines Textes belegen und <strong>zu</strong> anderen Verstehensweisen<br />

durch die literaturwissenschaftliche Fachsprache in Be<strong>zu</strong>g setzen <strong>zu</strong> können.<br />

WHAT DO YOU NEED TO DO LITERARY STUDIES'?<br />

Merritt Moseley. 1995. “Studying Literature.” In: Graham Atkin, Chris Walsh & Susan Watkins<br />

(eds.). Studying Literature: A Practical Introduction. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester<br />

Wheatsheaf, pp. 9-24; here p. 12; 20; 23:<br />

Disagreement is normal - as you will discover if you listen to any gathering of intellectuals -<br />

and is in fact the condition of discovery. That you disagree with received opinion is evidence<br />

neither that you are right nor that you are wrong; the important thing is to seek good grounds<br />

for our judgements and persuasive arguments to support them. [...] in your studies you will<br />

be be expec expected expec ted to to make make arguments for your own views, to engage in in in discussion, discussion, discussion, to read read critical<br />

essays essays which which differ differ from from your your own own opinions opinions and and from from each each other other - all all activities activities which which assume<br />

assume<br />

that that your your interpretation interpretation of of a a literary literary text text is is capable capable of of being being shared, shared, and and that that your your task task as a<br />

student student is is more more than than simply simply adopting adopting the the views views of of the the most most powerful po<br />

werful reader in sight.<br />

The most important kind of preparation is reading. Studying literature is primarily based<br />

on reading, including many kinds of texts. Read all the texts when you are asked to read<br />

them. There are many reasons why you should do this. One is that you will get far more more out<br />

of of lectures lectures and and seminars seminars if if you you have have have completely completely completely and and thoughtfully thoughtfully read read read the the text(s) text(s) being<br />

being<br />

addressed addressed in in them them. them You cannot understand a class, you cannot cannot take notes on on it, you cannot<br />

remember remember what what is is im important im portant in it, on on a a book book you have not not not read read. read [...] You cannot discuss a<br />

book intelligently if you have not read it. Lecturers appreciate students who come to class<br />

prepared to make a contribution.

Nieragden: ILCS 3<br />

WHY CAN LITERARY STUDIES SEEM SO CONFUSING? YOUR THOUGHTS:<br />

(a) Culler [1997:16-17]:<br />

Theory makes you desire mastery: you hope that theoretical reading will give you the concepts<br />

to organize and understand the phenomena that concern you. But theory makes mastery<br />

impossible, not only because there is always more to know, but, more specifically and<br />

more painfully, because theory is itself the questioning of presumed results and the assumptions<br />

on which they are based. The nature of theory is to undo, through a contesting of premisses<br />

and postulates, what you thought you knew, so the effects of theory are not predictable.<br />

You You have have not not become become master, master, but but neither neither are are you you you where where you you you were were before. before. You You reflect<br />

reflect<br />

on on your your reading reading in in new new ways. ways. You You have have different different questions questions<br />

to to ask ask and and a a better better sense sense of of the the<br />

the<br />

implications implications of of the the the questions questions you you put put to to works works you you read.<br />

read.<br />

(b) Ansgar Nünning. 1997. “On the Uses (and Abuses) of Theories and Metalanguages in<br />

Literary and Cultural Studies: Ten (teutonic) Hypotheses and Some Suggestions.” European<br />

English Messenger VI/2, pp. 25-32.<br />

1. Literary-historical ‘objects’ such as genres, genres, periods, periods, or or ‘movements’ ‘movements’ are are neither neither given given nor<br />

nor<br />

found, found, but but con constructed con structed by an observer who uses explicit theories theories or proceeds from intuitive<br />

assumptions. assumptions. 2. There here are are no no ap approaches ap<br />

proaches to to literature literature nor nor forms forms of of criticism criticism or or close close-reading<br />

close reading reading<br />

that that are are not not based based on on theoreti theoretical theoreti cal as assump as<br />

sump sumptions. sump tions. [...]<br />

► WHAT DO YOU YOU YOU YOU EXPECT FROM LEARNING ABOUT LTERARY STUDIES?<br />

.<br />

....

Nieragden: ILCS 4<br />

Theories Theories & Models in Literary St Studies St<br />

udies udies: udies : Research Research Research Landscapes<br />

Landscapes<br />

Landscapes<br />

Approaches<br />

Approaches<br />

EXTRATEXTUAL WORLD / HISTORICAL REALITY OTHER WORKS / TEXTS<br />

1 2<br />

WORK / TEXT<br />

(form ⇔ content) 5<br />

3 4<br />

PRODUCER / AUTHOR RECEIVER / READER<br />

APPROACH<br />

APPROACH<br />

1<br />

MIMETIC<br />

MIMETIC<br />

2<br />

INTERTEXTU<br />

INTERTEXTUAL<br />

INTERTEXTU<br />

INTERTEXTUAL<br />

AL; AL<br />

INTERMEDIAL<br />

INTERMEDIAL<br />

3<br />

EXPRESSIVE<br />

EXPRESSIVE;<br />

EXPRESSIVE<br />

SUBJECTIVE<br />

SUBJECTIVE<br />

4<br />

RECEPTIVE<br />

RECEPTIVE<br />

5<br />

AUTONOMOUS<br />

AUTONOMOUS<br />

AUTONOMOUS<br />

INTRINSIC<br />

INTRINSIC<br />

FORMALISTIC<br />

FORMALISTIC<br />

'WORKS' ARE: about related to by for constructed<br />

CONCEPT OF<br />

'WORK'<br />

RELATIONSHIP<br />

STUDIED<br />

a window on reality<br />

'work' ⇔<br />

'world'<br />

MAIN THEORIES -backgrounds: history,<br />

politics, culture,<br />

mentalities<br />

MODEL<br />

QUESTIONS<br />

-expression of ideologies(fundamentalism;<br />

marxism 1 ;<br />

feminism 2 ; postcolonialism<br />

3 )<br />

'Which attitude<br />

does the late-19 th<br />

Century American<br />

short story take to<br />

the recent Civil<br />

War (1861-65)?'<br />

a version of other<br />

works<br />

'work A' ⇔<br />

'work B'<br />

-literary history<br />

-genre history<br />

-sources or influences<br />

-use of topics &<br />

motifs<br />

-change to other<br />

media<br />

(=intermediality)<br />

'Compare the<br />

treatment of romantic<br />

love ideals<br />

in work x to that in<br />

work y'.<br />

produced by someone<br />

'work' ⇔<br />

'author'<br />

-use of biographical<br />

elements<br />

-psychoanalytical 4<br />

reading of author's<br />

personality<br />

-role in author's<br />

total œuvre<br />

'Which of her<br />

many professional<br />

disappointments<br />

did the author try<br />

to dramatize in her<br />

first full-length<br />

play?'<br />

received<br />

by someone<br />

'work' ⇔<br />

'reader'<br />

-reception<br />

history 5<br />

(whowhen-how)-censorship<br />

and<br />

availability<br />

-ideological<br />

employments<br />

'How would<br />

deeply religious<br />

readers respond<br />

to<br />

this poem's<br />

critique of<br />

Biblical stories?'<br />

having internal<br />

structure<br />

'form' ⇔<br />

'content'<br />

-structural<br />

analysis 6 :<br />

rhetorics; narratology;imagery;<br />

style<br />

'By which linguisticfeatures<br />

do contemporary<br />

sonnets deviate<br />

from traditionalexamples?'<br />

1-6<br />

= these six will be explained in more detail on the next page (keywords highlighted highlighted) highlighted<br />

►

Nieragden: ILCS 5<br />

► 1. 1.Marxist 1. Marxist Literary Literary Criticism Criticism = prime importance is given to the material living conditions<br />

(base), not to ideas or concepts (superstructure) ("existence determines essence");<br />

base = the underlying system of economic and technical forces; superstructure = arts, ideology,<br />

politics, family, religion etc.<br />

► in feudalistic and absolutist societies, literature is instrumentalized for reproducing (unjust)<br />

relations of power, and thus only cherishes an illusory version of freedom; in the course<br />

of the ongoing process of proletarian liberation, literature will be important for contesting<br />

power (of state, system, money, language) and thus overcoming false ideologies<br />

ideologies<br />

→ investigates 'constellations of economic exploitation the work shows to be in operation'<br />

2. 2. Feminist Criticism = blanket term for various schools which try<br />

to argue the special case of an écriture écriture écriture écriture féminine féminine féminine féminine (re-study women authors; re-discover neglected<br />

women authors; provide a female countercanon; 'der schielende Blick');<br />

to investigate images of women in male writing (stereotyping; suppression; 'Alice in Genderland');<br />

to question the very difference of biological (sex sex sex) sex and sociological (gender gender gender) gender role conceptions<br />

and want to overcome the heteronormative and patriarchic patriarchic structures of ('phallocentrism') of<br />

arts and society<br />

→ investigates '[wo]men producing, populating, receiving work'<br />

3. 3. 3. Postcolonialism = approaches which focus on the (literary) relationship of domina domination domina<br />

tion vs.<br />

suppression suppression as evident in literature from the Colonizer's as well as the Colonized's perspectives;<br />

categorising racial, explorer's, civilsatory and religious cli clichés cli<br />

chés<br />

► assesses the absence of heterogeneity<br />

heterogeneity and diversity diversity diversity in 'Colonialism/Orientalism' and<br />

their promotion in 'Post-Colonial' Works<br />

→ investigates 'political First and Third World history as evident in work'<br />

4. 4. 4. Psychoanalytical Psychoanalytical Criticism = categorising and 'diagnosing' author's (and characters') decisions<br />

and behaviour through Freudian Analysis, i.e. literary texts become symptoms of an<br />

author's unconscio unconscious<br />

unconscio<br />

us us and his phantasies, dreams, fears, 'neuroses' find expression in recurrent<br />

motifs – works are results of sublimation<br />

sublimation and repres repression repres sion of hidden desires:<br />

Id: passionate, irrational and non-reflective part; source of instinctual physical drives; Superego:<br />

internalized societal norms and mores; outer framework of rules and standards;<br />

Ego: rational, logical and conscious part; mediator between the competing demands of Id<br />

and Superego<br />

► Id's desires are repressed and are forced into the unconscious from where they emerge<br />

as in disguised form (e.g. dreaming, creative acts); symbols need to be 'decoded' [see also:<br />

C.G. Jung (archetypal criticism ~the collective unconscious); Northrop Frye (myth criticism)]<br />

→ investigates 'latent & unspoken desires hidden under the surface of the work'<br />

5. 5. Rea Reader Rea<br />

der Response Response Response Theory Theory = based on the principle that all real readers form part of a in-<br />

terpretive terpretive community community having access to the same language, interpretive strategies and<br />

reading socialization; these, together, provide the reader with a horizon horizon of expectations<br />

expectations<br />

► literary texts are of particular interest when they run counter to this horizon (content,<br />

structure, formal level); all literary texts –due to their ambiguous and allusive use of language<br />

– present gaps gaps gaps (Leerstellen) which readers have to fill acc. to their horizons<br />

→ investigates 'readers' changing reaction to work'<br />

6. 6. Formalism Formalism = the critical practice of focusing on the artistic/linguistic technique of the text;<br />

centering on the internal mechanics of the work, not the extratextual semantics and ideologies<br />

(e.g. rhetorical, linguistic analysis, discourse analysis, syntax // tense usage in a novel;<br />

turn-taking in a play, metaphors // rhymes // layout in a poem)<br />

defamiliarization defamiliarization = literary texts use language differently from ordinary, everyday speech;<br />

this slows down, estranges and impedes the the reader's relation to the text; and is<br />

achieved through; foregrounding foregrounding = devices are put into special focus and thus receive the<br />

reader's attention; their most central one becomes the dominant of a text which generates<br />

the latter's cstructral coherence and unique character<br />

→ investigates 'material composition of work'

Nieragden: ILCS 6<br />

Self Self-Study Self Study 1: : : Which Which Approaches Approaches (s. pp.<br />

p<br />

. 4) 4) are at the centre centre of<br />

these these 15 15 questions questions questions that that are are typically typically asked asked in in literary literary studies? studies?<br />

studies?<br />

1 How do we react to poetry calling the sun "the eye of heaven" ?<br />

2 What do we learn about pre- and post-9/11 New York City from reading<br />

the novel Falling Man ?<br />

3 Do we read the novel Robinson Crusoe differently if<br />

-we are non-white ? -we are islanders ? -we are marxists ?<br />

-we have seen a movie version first ?<br />

4 Which idea(l)s of childhood are latent in Harry Potter<br />

and the Philosopher's Stone ?<br />

5 Why was drama chiefly written in verse before the late 19 th Century ?<br />

6 Why can we not put down a thrilling detective novel before we know the<br />

murderer ?<br />

7 What does it mean if Romeo and Juliet is staged in con-<br />

temporary setting and costumes ?<br />

8 How many readers buy literature on grounds of media fame and prizes ?<br />

9 Do Jane Austen's novels appeal more to young female readers ?<br />

10 Will the trend for 'reading circles' and 'audio books' last for long ?<br />

11 Which poets dominated the movement of early 19 th Century Romanticism ?<br />

12 Are there only medial/visual changes, or principal ones beteen the (print) novel and the<br />

graphic novel ?<br />

13 Has Northern Irish Poetry helped resolve the political<br />

conflicts within the country ?<br />

14 Where has literature influenced music, painting, architecture ?<br />

15 Can the recent productions of 'Twitterature' (=narrative fiction in 140<br />

digits) motivate the 'digital natives' to read more literature ?<br />

YOUR YOUR YOUR YOUR ANSWERS:<br />

ANSWERS:<br />

ANSWERS:<br />

ANSWERS:<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

4.<br />

5.<br />

6.<br />

7.<br />

8.<br />

9.<br />

10.<br />

11.<br />

12.<br />

13.<br />

14.<br />

15.

Nieragden: ILCS 7<br />

Bibliographic Bibliographic References: References: Recommended Recommended Recent Recent Works Works (post (post-2000)<br />

(post 2000)<br />

Self Self-Study Self Study 2: : Observe Observe Observe the the subtle subtle diffe differences diffe rences in book book titles;<br />

check check out out a a number number of of them them them in in our our seminar seminar library<br />

library<br />

1. INTRODUCTIONS & OVERVIEWS<br />

Gymnich, Marion & Ansgar Nünning (eds.). 2005. Funktionen von Literatur - Theoretische Grundlagen und Modellinterpretationen.<br />

Trier: WVT.<br />

Hebel, Udo. 2008. Einführung in die Amerikanistik/American Studies. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

Hofmann, Michael. 2006. Interkulturelle Literaturwissenschaft. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: UTB.<br />

Jahraus, Oliver. 2004. Literaturtheorie. Theoretische und Methodische Grundlagen der Literaturwissenschaft.<br />

Stuttgart: UTB.<br />

Klarer, Mario. 5 2007 [ 1 1994]. Einführung in die anglistisch-amerikanistische Literaturwissenschaft. Darmstadt:<br />

WBG.<br />

Korte, Barbara, Klaus Peter Müller & Josef Schmied. 2 2004 [ 1 1997]. Einführung in die Anglistik. Methoden, Theorien<br />

und Bereiche. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

Meyer, Michael. 3 2008 [ 1 2003]. English and American Literatures. Tübingen: A. Francke.<br />

Nünning, Ansgar (ed.). 4 2004 [ 1 1995]. Literaturwissenschaftliche Theorien, Modelle und Methoden. Trier: WVT.<br />

Nünning, Vera & Ansgar. 2005. An Introduction to the Study of English and American Literature. Stuttgart: Klett.<br />

Schneider, Ralf (ed.). 2004. Literaturwissenschaft in Theorie und Praxis. Eine anglistisch-amerikanistische<br />

Einführung. Tübingen: Narr.<br />

Schößler, Franziska. 2006. Literaturwissenschaft als Kulturwissenschaft. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: UTB.<br />

2. GLOSSARIES, LEXICONS & TERMINOLOGICAL HANDBOOKS<br />

Abrams, M.H. 7 2008 [ 1 1957]. A Glossary of Literary Terms. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.<br />

Beck, Rudolf, Hildegard Kuester & Martin Kuester. 2007. Basislexikon Anglistische Literaturwissenschaft.<br />

Stuttgart: UTB.<br />

Childs, Peter, Jean Jaques Weber & Patrick Williams. 2006. Post-Colonial Theory and Literatures - African,<br />

Caribbean and South Asian. Trier: WVT.<br />

Engler, Bernd & Kurt Müller (eds.) 2000. Metzler Lexikon amerikanischer Autoren. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

Kreutzer, Eberhard & Ansgar Nünning (eds.) 2002. Metzler Lexikon englischsprachiger Autoren. Stuttgart:<br />

Metzler.<br />

Nünning, Ansgar (ed.). 4 2008 [ 1 1998]. Metzler Lexikon Literatur- und Kulturtheorie. Ansätze-Personen-Grundbegriffe.<br />

Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

3. LITERARY HISTORY: NATIONAL LITERATURES<br />

Alexander, Michael. 2000. A History of English Literature. Basingstoke: Palgrave.<br />

Carter, Ronald & John McRae. 2 2001 [ 1 1997]. The Routledge History of Literature in English: Britain and Ireland.<br />

London: Routledge.<br />

Döring, Tobias (ed.). 2007. A History of Postcolonial Literature in 12 ½ Books. Trier: WVT.<br />

Drabble, Margaret (ed.). 6 2000 [ 1 1932]. The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford: OUP.<br />

Eckstein, Lars (ed.). 2007. English Literatures Across the Globe. A Companion. Stuttgart: UTB.<br />

Erlebach, Peter , Bernhard Reitz & Thomas M. Stein. 2004. Geschichte der englischen Literatur. Stuttgart:<br />

Reclam.<br />

Gymnich, Marion, Birgit Neumann & Ansgar Nünning (eds.). 2007. Gattungstheorie und Gattungsgeschichte.<br />

Trier: WVT.<br />

Kosok, Heinz. 2008. Explorations in Irish Literature. Trier: WVT.<br />

Löschnigg, Maria & Martin. 2002. Kurze Geschichte der Kanadischen Literatur. Stuttgart: Klett.<br />

Nowak, Helge. 2006. Geschichte der literarischen Kommunikation - Zur Neukonzeption einer Geschichte der<br />

englischsprachigen Literaturen. Trier: WVT.<br />

Nünning, Ansgar. (ed.). 3 2004 [ 1 1996]. Eine Andere Geschichte der englischen Literatur. Epochen, Gattungen<br />

und Teilgebiete im Überblick. Trier. WVT.<br />

Nünning, Vera. 2005. Kulturgeschichte der englischen Literatur: Von der Renaissance bis <strong>zu</strong>r Gegenwart. Tübingen:<br />

A. Francke.<br />

Head,. Dominic (ed.). 3 2006 [ 2 1993]. The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English. Cambridge: CUP.<br />

Poddar, Prem & David Johnson (eds.). 2008. A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures in English.<br />

Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.<br />

Schabert, Ina. 2006. Englische Literaturgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Eine neue Darstellung aus Sicht der<br />

Geschlechterforschung. Stuttgart: Kröner.<br />

Seeber, Hans Ulrich (ed.). 4 2004 [ 1 1991]. Englische Literaturgeschichte. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

Stein, Mark. 2004. Black British Literature: Novels of Transformation. Columbus, OH: Ohio State UP.<br />

Zapf, Hubert (ed.). 2 2004 [ 1 1996]. Amerikanische Literaturgeschichte. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

Buying Buying Recommendation: Recommendation: Wagner, Hans-Peter. 2 2010 [ 1 2003]. A History of British, Irish and American Literature.<br />

Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier. *** 590 pp., 160 illustrations (incl. CD-ROM with full text<br />

and 480 illustrations); €32,50.

Literary Literary History History & & Literary Literary Histories<br />

Histories<br />

Period Period Models Models Models of of English English Literary Literary History<br />

History<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 8<br />

(a) (1937) (b) (1991) (c) (1991)<br />

Die altenglische Zeit XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Altenglische Lit<br />

Die mittelenglische Zeit Mittelalter Mittelenglische Lit<br />

Die Zeit der Renaissance Renaissance Die Frühe Neuzeit: Von Morus bis Milton<br />

Die Zeit des Barocks Restaurationszeit und 18. Jh Von der Restauration <strong>zu</strong>r Vorromantik<br />

Der Klassizismus XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX<br />

Die Romantik Romantik Romantik und viktorianische Zeit<br />

Das neunzehnte Jh Viktorianisches Zeitalter XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Vormoderne und Moderne<br />

Das zwanzigste Jh 20. Jh Die Zeit nach 1945<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Commonwealth-Lit<br />

(d) (1996) (e) 2000<br />

Old English Lit I MEDIEVAL: Old English Lit to 1100<br />

Medieval Lit 1066-1510 Middle English Lit 1066-1500<br />

Renaissance and Reformation: Lit 1510-1620 <strong>II</strong> TUDOR & STUART: Tudor Lit 1500-1603<br />

Revolution and Restoration: Lit 1620-1690 Shakespeare and the Drama<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Stuart Lit to 1700<br />

Eighteenth-Century Lit 1690-1780 <strong>II</strong>I AUGUSTAN & ROMANTIC: Augustan Lit to 1790<br />

The Lit of the Romantic Period 1780-1830 The Romantics 1790-1837<br />

High Victorian Lit 1830-1880 IV VICTORIAN LIT TO 1880: The Age and its Sages<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Poetry<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Fiction<br />

Late Victorian and Edwardian Lit 1880-1920 Late Victorian Lit 1880-1900<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX V THE 20TH CENTURY: Ends a. Beginnings: 1901-1919<br />

Modernism and its Alternative: Lit 1920-1945 From Post-War to Post-War: 1920-1955<br />

Post-War and Post-Modern Lit New Beginnings: 1955-1980<br />

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Postscript on the Current<br />

(f) Generally Accepted Model in Contemporary Criticism (from various sources) ► (s. (s. pp. 99-11<br />

9<br />

11 ! !) !<br />

450-1066 Old English (or Anglo-Saxon) Period<br />

1066-1500 Middle English Period<br />

1500-1660 The Renaissance<br />

1558-1603 Elizabethan Age<br />

1603-1625 Jacobean Age<br />

1625-1649 Caroline Age<br />

1649-1660 Commonwealth Period (or Puritan Interregnum)<br />

1660-1785 The Neoclassical Period<br />

1660-1700 The Restoration<br />

1700-1745 The Augustan Age (or Age of Pope)<br />

1745-1785 The Age of Sensibility (or Age of Johnson)<br />

1785-1830 The Romantic Period<br />

1832-1901 The Victorian Period<br />

1848-1860 The Pre-Raphaelites<br />

1880-1901 Aestheticism and Decadence<br />

1901-1914 The Edwardian Period<br />

1910-1936 The Georgian Period<br />

1914-1939 The Modern Period<br />

1945- Postmodern Period<br />

(a) Schirmer, Walter F. 2 1968 [ 1 1937 1937]. 1937 Kurze Geschichte der englischen und amerikanischen<br />

Literatur. Von den Anfängen bis <strong>zu</strong>r Gegenwart. 2 Bände. München & Tübingen: A. Francke.<br />

(b) Fabian, Bernhard. (ed.). 1991 1991. 1991<br />

Die englische Literatur. Bd. 1: Epochen, Formen. München: dtv.<br />

(c) Seeber, Hans Ulrich (ed.). 1991 1991. 1991<br />

Englische Literaturgeschichte. Stuttgart: Metzler.<br />

(d) Sanders, Andrew. 1996 1996. 1996 The Short Oxford History of English Literature. Oxford: OUP.<br />

(e) Alexander, Michael. 2000 2000. 2000 A History of English Literature. Basingstoke:<br />

Palgrave.

Nieragden: ILCS 9<br />

A A Detailed Detailed Account Account Account of of Major Major Periods Periods and and and Authors Authors in in English English English Literary Literary Literary History<br />

History<br />

Self Self-Study Self Study 3: : Carefully read through these passages passages and select<br />

one one period period that that seem seems seem of particular particular interest interest to you you. you<br />

The Old Old English English (or (or Anglo Anglo-Saxon) Anglo Saxon) Period Period (450-1066) refers to the literature produced from<br />

the invasion of Celtic England by Germanic tribes in the first half of the fifth century to the<br />

conquest of England in 1066 by William the Conqueror. During this period, written literature began<br />

to develop from oral tradition, and in the 8th century poetry written in the vernacular<br />

Anglo-Saxon (also known as Old English) appeared. One of the best-known texts Beowulf ,<br />

a great Germanic epic poem. Two poets of the Old English Period who wrote on biblical and<br />

religious themes and are still studied are Caedmon and Cynewulf .<br />

The Middle English Period (1066-1500) consists of the literature produced in the four<br />

and a half centuries between the Norman Conquest of 1066 and about 1500, when the<br />

standard literary language, derived from the dialect of the London area, became recognizable.<br />

Prior to the second half of the 14th century, vernacular literature consisted primarily<br />

of religious writings. The second half of the fourteenth century produced the first great age<br />

of secular literature including ballads, chivalric romances, allegorical poems, and a variety of<br />

religious plays. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is the most celebrated work of<br />

this period; still studied are the anonymous Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Thomas<br />

Malory's Morte d' Arthur .<br />

While the English Renaissance began with the ascent of the House of Tudor to the<br />

English throne in 1485, the English Lite Literary Lite<br />

rary Renaissance Renaissance (1500 (1500-1660)<br />

(1500 1660) began with English<br />

humanists such as Sir Thomas More and Sir Thomas Wyatt. In addition, this period is generally<br />

organised into four subsets: The Elizabethan Age, the Jacobean Age, the Caroline Age,<br />

and the Commonwealth Period (also known as the Puritan Interregnum).<br />

The Elizabethan Elizabethan Age coincides with the reign of Elizabeth I from 1558 to 1603. During<br />

this time, medieval tradition was blended with Renaissance optimism. Lyric poetry,<br />

prose, and drama were the major styles of literature that flowered during the Elizabethan<br />

Age. Some important writers of the Elizabethan Age include, next to William Shakespeare,<br />

Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Ben Jonson.<br />

The Jacobean Age coincides with the reign of James I from 1603 to 1625. During<br />

this time literature became sophisticated, sombre, and conscious of social abuse and rivalry.<br />

The Jacobean Age produced rich prose and drama as well as the King James<br />

translation of the Bible. Shakespeare and Jonson continued writing into this period whose most<br />

significant writers are John Donne, Francis Bacon, and Thomas Middleton.<br />

The Caroline Age coincides with the reign of Charles I from 1625 to 1649. The writers<br />

of this age wrote with refinement and elegance. This era mainly produced a circle of<br />

poets known as the "Cavalier Poets"; the dramatists of this age were the last to write in<br />

the Elizabethan tradition.<br />

The Commonwealth Period Period includes the literature produced during the rule of Puritan<br />

leader Oliver Cromwell from 1949 to 1660. This period produced the political writings<br />

of John Milton, Thomas Hobbes' political treatise Leviathan, and the prose of Andrew<br />

Marvell. In September of 1642, the Puritans closed theatres on moral and religious<br />

grounds. For the next eighteen years the theatres remained closed, accounting for the<br />

lack of drama produced during this time period.<br />

The Neoclassical Period (1660 (1660-1785)<br />

(1660<br />

1785) 1785) was much influenced by contemporary French literature,<br />

which was in the midst of its greatest age. The literature of this time is known for its<br />

use of philosophy, reason, skepticism, wit, and refinement. The period also marks the first<br />

great age of English literary criticism.Much like the English Literary Renaissance, the<br />

Neoclassical Period can be divided into three subsets: the Restoration, the Augustan Age,<br />

and the Age of Sensibility.<br />

The Restoration<br />

Restoration Restoration (1660–1700) is marked by the restoration of the monarchy and the triumph<br />

of reason and tolerance over religious and political passion. The Restoration produced<br />

an abundance of prose and poetry and the distinctive comedy of manners known as<br />

Restoration comedy. It was during the Restoration that John Milton published Paradise Lost

Nieragden: ILCS 10<br />

and Paradise Regained. Other major literary writers of the era include John Dryden and<br />

John Wilmot, 2 nd Earl of Rochester.<br />

The Augustan Augustan Age (1700-1745) derives its name from the brilliant literary period<br />

of Vergil and Ovid under the Roman emperor Augustus (27 B.C. - A.D. 14). In English<br />

literature, this age refers to literature with the predominant characteristics of refinement,<br />

clarity, elegance, and balance of judgement. Well-known writers of the Augustan Age<br />

include Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe. A significant contribution of<br />

this time period included the release of the first English novels by Defoe, and the "novel<br />

of character," Pamela, by Samuel Richardson in 1740.<br />

During the Age Age of Sensibility Sensibility (1745-1785), literature reflected the worldview<br />

of the Enlightenment and began to emphasize instict and feeling, rather than judgment<br />

and restraint. A growing sympathy for the Middle Ages during the Age of Sensibility<br />

sparked an interest in medieval ballads and folk literature. Another name for this period<br />

is the Age of Johnson because the dominant authors of this period were Samuel Johnson<br />

and his literary and intellectual circle. This period also produced some of the greatest<br />

early novels of the English language, including Richardson's Clari sa (1748) and Henry<br />

Fielding's Tom Jones (1749).<br />

The Romantic Period (1785-1832) began in the late 18th century and lasted for ca. 50<br />

years. In general, Romantic literature can be characterized by its personal nature, its stong<br />

use of feeling, its abundant use of symbolism, and its exploration of nature and the supernatural.<br />

In addition, the writings of the Romantics were considered innovative based on their<br />

belief that literature should be spontaneous, imaginative, personal, and free. The Romantic<br />

Period produced a wealth of authors including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth,<br />

Jane Austen, and Lord Byron. It was during the Romantic Period that Gothic literature was<br />

born. Traits of Gothic literature are dark and gloomy settings and characters and situations that<br />

are fantasic, grotesque, wild, savage, mysterious,and often melodramatic. Two of the most<br />

famous Gothic novelists are Anne Radcliffe and Mary Shelley.<br />

The Victorian Victorian Period began with the accession of Queen Victoria to the throne in 1837, and<br />

lasted until her death in 1901. As it spans over six decades, the year 1870 is often used to<br />

divide the era into "early Victorian" and "late Victorian." In general, Victorian literature deals<br />

with the issues and problems of the day. Some contemporary issues that the Victorians<br />

were concerned with include the social, economic, religious, and intellectual issues<br />

and problems surrounding the Industrial Revolution, growing class tensions, the early feminist<br />

movement, pressures toward political and social reform, and the impact of Charles<br />

Darwin's theory of evolution on philosophy and religion. Some of the most recognized<br />

authors of the Victorian era include Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, her<br />

husband Robert, Matthew Arnold, Charles Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and<br />

Thomas Hardy.<br />

In 1848, a group of English artists, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, formed the "Pre Pre Pre- Pre<br />

Ra Raphaelite Ra<br />

phaelite Brotherhood<br />

Brotherhood." Brotherhood<br />

It was the aim of this group to return painting to a style of<br />

truthfulness, simplicity, and religious devotion that had reigned prior to Raphael and the<br />

high Italian Renaissance. Rossetti and his literary circle, which included his<br />

sister Christina, incorporated these ideals into their literature (until 1860).<br />

The Aestheticism and Decadence movement movement grew out of the French movement<br />

of the same name. The authors of this movement encouraged experimentation and held<br />

the view that art is totally opposed to "natural" norms of morality. This style of literature<br />

opposed the dominance of scientific thinking and defied the hosility of society to any art<br />

that was not useful or did not teach moral values. It was from this movement that the<br />

phrase art for art's sake emerged. The best-known author here is Oscar Wilde.<br />

The Edwardian Edwardian Period Period is named for King Edward V<strong>II</strong> and spans the time from Queen<br />

Victoria's death (1901) to the beginning of World War I (1914). During this time, the British<br />

Empire was at its height and the wealthy lived lives of materialistic luxury. However, four<br />

fifths of the English population lived in squalor. The writings of the Edwardian Period reflect<br />

and comment on these social conditions. For example, writers such as George Bernard<br />

Shaw and H.G. Wells attacked social injustice and the selfishness of the upper classes. Other<br />

writers of the time include William Butler Yeats, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, Henry James,<br />

and E.M. Forster .

Nieragden: ILCS 11<br />

The Georgian Period Period refers to the period of British Literature that is named for the reign<br />

of George V (1910-36). Many writers of the Edwardian Period continued to write during the<br />

Georgian Period . This era mainly produced a group of poets known as the Georgian poets.<br />

Georgian poetry tends to focus on rural subject matter and is traditional in technique and<br />

form.<br />

The Modern Period applies to British literature written between the end of World War I<br />

(1914) and the beginning of World War <strong>II</strong> (1939). The authors experimented with subject<br />

matter, form, and style and have produced achievements in all literary genres. They proposed<br />

a radical breaks with traditional modes of Western art, thought, religion, social conventions,<br />

and morality. Poets of the period include Yeats, T.S. Eliot, and Dylan Thomas. Novelists<br />

include James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf .<br />

Following World War <strong>II</strong> (1939-1945), the Postmodern Period developed. Postmodernism blends<br />

literary genres and styles and attempts to break free of modernist forms. While the British<br />

literary scene at the turn of the new millenium is crowded and varied, the authors still fall<br />

into the categories of modernism and postmodernism. However, with the passage of time the<br />

Modern era may be reorganized and expanded.<br />

FYI FYI 11:<br />

1<br />

: American Lite Literary Lite<br />

rary History History in (rough...) Overview<br />

1607-1776: Colonial Period<br />

1765-1790: The Revolutionary Age<br />

1775-1828: The Early National Period<br />

1828-1865: The Romantic Period (aka: Ame. Renaissance / Age of Transcendentalism)<br />

1865-1900: The Realistic Period<br />

1900-1914: The Naturalistic Period<br />

1914-1939: American Modernist Period<br />

1920s: Jazz Age, Harlem Renaissance<br />

1920s, 1930s: The "Lost Generation"<br />

1939-present: The Contemporary Period<br />

1950s: Beat Writers<br />

1960s, 1970s: Counterculture<br />

In addition, American Literature recognizes writers of specific origins:<br />

African-American Native American Asian-American Hispanic-American<br />

FYI FYI 22:<br />

2<br />

: And don't forget: English is the literary language of roughly half the globe and<br />

is is constantly constantly contributing contributing to to the the body body body of of 'New 'New Li Literatures Li teratures in in English'....<br />

English'....

Genre Genre 1: 1: Theory Theory & & & Terminology<br />

Terminology<br />

1.1 1.1 Communicative Situations of Main Literary Genres<br />

1. 1. 1. POETRY = "Lyrik; Poesie; Dichtung" (s.pp. 13-16)<br />

EXTERNAL LEVEL OF NONFICTIONAL COMMUNICATION<br />

INTERNAL LEVEL OF POEM<br />

SPEAKER / PERSONA ⇒ ADDRESSEE<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 12<br />

AUTHOR (= POET) ⇒ READER<br />

2. 2. DRAMA DRAMA = "Dramatik; Schauspiel; Theater" (s.pp. 17 17-20 17<br />

20 20) 20<br />

EXTERNAL LEVEL OF NONFICTIONAL COMMUNICATION<br />

INTERNAL LEVEL OF ACTION<br />

CHARACTER ⇔ CHARACTER<br />

AUTHOR (= PLAYWRIGHT) ⇒ READER / SPECTATORS*<br />

3. 3. NARRATIVE<br />

ARRATIVE = "Epik; Erzählliteratur" (s. s. pp. pp. 20 20-22 20 22 22) 22<br />

EXTERNAL LEVEL OF NONFICTIONAL COMMUNICATION<br />

INTERNAL LEVEL OF FICTIONAL MEDIATION (= DISCOURSE)**<br />

***<br />

INTERNAL LEVEL OF ACTION (= STORY)***<br />

CHARACTER ⇔ CHARACTER<br />

NARRATOR ⇒ NARRATEE<br />

AUTHOR (= NOVELIST) ⇒ READER<br />

*= DRAMA IS, BY STANDARD DEFINITION, SEEN AND HEARD IN A COLLECTIVE<br />

RECEPTION PROCESS<br />

** **= **<br />

HOW IT IS TOLD<br />

*** ***= ***<br />

WHAT IS TOLD<br />

** **

1.2 1.2 Poetry: Elementaries of Rhyme<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 13<br />

1. RHYME TYPES<br />

1.1. Pure rhyme [REINER REIM]<br />

Words with perfect identity of sound in stressed syllables. It is also known as perfect rhyme.<br />

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood ood ood, ood end rhyme [ENDREIM]<br />

And sorry that I could not travel both,<br />

And be one traveler, long I stood ood ood<br />

And looked down as far as I could ould ould” ould<br />

(Robert Frost, “The Road Not Taken”)<br />

“I am the daughter aughter of Earth and Water ater ater, ater internal rhyme [BINNENREIM]<br />

And the nursling of the Sky;<br />

I pass through the pores ores of the ocean and shores ores ores” ores (Percy B. Shelley, “The Cloud”)<br />

“Then all averred, I had killed the bird identical rhyme [IDENTISCHER REIM]<br />

That brought the fog and mist mist. mist<br />

‘Twas right, said they, such birds to stay,<br />

That bring the fog and mist mist” mist<br />

(Samuel Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”)<br />

1.2 Imperfect Rhyme [UNECHTER REIM]<br />

Alliteration [ALLITERATION]<br />

The repetition of a consonant at the beginning of neighbouring words (= initial half rhyme).<br />

“Five miles meandering with a mazy motion” (Samuel Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”)<br />

“Do not go gentle into that good night” (Dylan Thomas, “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night”)<br />

Assonance [ASSONANZ]<br />

The repetition of a vowel at the beginning or in stressed syllables of neighbouring words (= half<br />

rhyme).<br />

“A miner on the dole,<br />

with nowhere to go” (Bryn Griffiths, “On the Dole”)<br />

“twice five miles of fertile ground” (Samuel Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”)<br />

Consonance [KONSONANZ]<br />

The repetition of the same conso consonant conso<br />

nant before and/or after differing stressed vowels<br />

“It seemed that out of battle I esc sc scaped sc<br />

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since sc scooped sc<br />

Through granites which titanic wars had gr groined. gr<br />

Yet also there encumbered sleepers gr groaned” gr (Wilfried Owen, “Strange Meeting”)<br />

Assonance, alliteration and consonance are very frequent in idioms (‘as dead as a doornail’; ‘cold as<br />

a stone’), advertising (‘Guinness is good for you’; ‘fish n’ chips’; ‘Beanz nz meanz nz Heinz nz nz’), nz tongue twisters<br />

(‘Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled pepper’; ‘Round the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran’),<br />

and onomatopoetic language (‘kn kn knick kn ck ck-kn ck kn knack kn ck ck’). ck<br />

Eye Rhyme [AUGENREIM]<br />

Words which look like a pure rhyme, but only have identical spellings, not identical sounds (e.g.<br />

great/meat; find/wind).<br />

“Dull would he be of soul who could pass by<br />

A sight so touching in its majesty ty ty” ty<br />

(William Wordsworth, “Composed Upon Westminster Bridge)<br />

“Strong gongs groaning as the guns boom far ar ar, ar<br />

Don John is going to war ar ar” ar<br />

(Gilbert K. Chesterton, “Lepanto”)

2. RHYME SCHEMES<br />

Alternate rhyme [KREUZREIM]<br />

(a b a b)<br />

“If I could write the beauty of your eyes<br />

and in fresh numbers number all your graces graces<br />

The age to come would say, ‘This poet lies lies; lies<br />

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces faces” faces (Shakespeare, “Sonnet 17”)<br />

Enclosed rhyme [UMARMENDER REIM]<br />

(a b b a)<br />

“Call us what you will, we are made by such love love; love<br />

Call her one, me another fly fly, fly<br />

We’re tapers too, and at our own cost die die, die<br />

And we in us find th’eagle and the dove dove” dove<br />

(John Donne, “The Canonization”)<br />

Couplets [PAARREIM]<br />

(a a b b c c)<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 14<br />

“Sweet smiling village, loveliest of the lawn, lawn<br />

Thy sports are fled, and all thy charms withdrawn drawn drawn; drawn<br />

Amidst thy bowers the tyrant’s hand is seen seen, seen<br />

And desolation saddens all thy green green” green (Oliver Goldsmith, “The Deserted Village”)<br />

Sonnet [SONETT]<br />

A lyric poem that consists of 14 lines in a single stanza, often used to express personal feelings of<br />

love, religious devotion, metaphysical anguish, and lamentation for the dead. In English poetry, the<br />

most important patterns are:<br />

(a b b a a b b a c d c d c d) 1 octave; 1 sestet John Milton; William<br />

Wordsworth, Dante G. Rossetti<br />

(a b a b b c b c c d c d e e) 3 quatrains; 1 couplet Edmund Spenser<br />

(a b a b c d c d d e d e g g) 3 quatrains; 1 couplet William Shakespeare,<br />

John Donne, W.H. Auden,<br />

Rhyme royal<br />

(a b a b b c c) Geoffrey Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde<br />

Spenserian stanza<br />

(a b a b b c b c c) Edmund Spenser, James Thomson, John Keats<br />

Terza rima<br />

(a b a b c b c d c) Thomas Wyatt, Jon Milton, Robert Browning, T.S.<br />

Eliot<br />

Ottava rima<br />

(a b a b a b c c) Thomas Wyatt, Lord Byron<br />

Masculine rhyme [MÄNNLICHE KADENZ]<br />

The last syllable of the rhyming word (= mostly monosyllabic) is stressed.<br />

"bright - light; wood - stood; three - tea; june - moon; desire – fire"<br />

Feminine rhyme [WEIBLICHE KADENZ]<br />

The last syllable of the rhyming word (= mostly polysyllabic) is unstressed.<br />

"brightly - lightly; mother - brother; daughter - water; ending - bending; seventeen - Levantine; comparison<br />

– garrison"

1.3 1.3 Poetry: Poetry: Rhetorical Rhetorical Figures<br />

Figures<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 15<br />

Die Die wi wichtigsten wi wi chtigsten rhetorischen rhetorischen Figuren Figuren 1 1 (Central (Central figures figures of speech) speech) DEFINITIONS<br />

(A) PHONOLOGISCHE FIGUREN (PHONOLOGICAL FIGURES)<br />

Alliteration (alliteration) Gleicher Anlaut aufeinderfolgender Wörter<br />

Assonanz (assonance) Häufung gleicher Vokale in betonten Silben<br />

Konsonanz (consonance) Häufung gleicher Konsonanten in Umgebung verschiedener<br />

betonter Vokale<br />

Onomatopoesie (onomatopoiea) Lautmalerische Nachahmung der Geräusche, die das Geschilderte<br />

typischerweise hervorbringt<br />

(B) MORPHOLOGISCHE FIGUREN (MORPHOLOGICAL FIGURES)<br />

Anapher (anaphora) Wortwiederholung am Anfang mehrerer aufeinanderfolgender<br />

Verse (Sätze, Absätze)<br />

Geminatio (geminatio) Unmittelbare Wiederholung eines Wortes<br />

Epanalepse (epanalepsis) Wortwiederholung am Anfang und Ende (eines Satzes, Verses,<br />

Absatzes)<br />

Epipher (epiphora) Wortwiederholung am Ende mehrerer aufeinanderfolgender<br />

Verse (Sätze, Absätze)<br />

Polyptoton (polyptoton) Wiederaufnahme eines Wortes in verschiedenen Flexionsformen<br />

(C) SYNTAKTISCHE FIGUREN (SYNTACTIC FIGURES)<br />

Asyndeton (asyndeton) Unverbundene (ohne Konjunktionen) Reihung mehrerer<br />

referenzgleicher Attribute<br />

Chiasmus (chiasm) Spiegelbildliche Anordnung identischer syntaktischer Strukturen;<br />

Kreuzstellung (abc; cba)<br />

Ellipse (ellipsis) Unvollständiger Satzbau, d.h. Weglassen von spezifischen<br />

Elementen<br />

Parallelismus (parallelism) Wiederholung identischer syntaktischer Strukturen (abc; abc)<br />

Polysyndeton (polysyndeton) Verbundene (mit Konjunktionen) Reihung mehrerer<br />

referenzgleicher Attribute<br />

Zeugma (zeugma) Ein Verb regiert mehrere, semantisch nicht ‘<strong>zu</strong>sammenpassende’<br />

Objekte<br />

(D) SEMANTISCHE FIGUREN (SEMANTIC FIGURES)<br />

Euphemismus (euphemism) Beschönigende Beschreibung<br />

Hendiadyoin (hendiadys) Zwei referenzähnliche bzw. -identische Ausdrücke durch Konjunktion<br />

verbunden <strong>zu</strong>r Benennung eines Sachverhalts<br />

Katachrese (catachresis) ‘Unpassende’ Kongruenz von Subjekt und Verb; führt <strong>zu</strong><br />

‘mißglückten’ sprachlichen Bildern<br />

Metapher (metaphor) Verkürzter, impliziter Vergleich; Verknüpfung zweier<br />

divergierender Bildbereiche<br />

Metonymie (metonymy) Erset<strong>zu</strong>ng durch kausal, spatial, temporal, logisch o.ä.<br />

verwandten Begriff<br />

Oxymoron (oxymoron) Unmittelbare Verbindung einander widersprechender Ausdrücke<br />

Personifikation (personification) Belebung/Vermenschlichung eines Dings oder Abstraktums<br />

Pleonasmus (pleonasm) (Überflüssige) Häufung referenzähnlicher oder -identischer<br />

Ausdrücke<br />

Simile (simile) Ausführlicher, expliziter Vergleich; Verknüpfung zweier<br />

divergierender Bildbereiche<br />

Synästhesie (synesthesia) Vermischung verschiedener Sinneswahrnehmungen<br />

Synekdoche (synecdoche) Erset<strong>zu</strong>ng durch einen engeren, partikularisierenden (pars pro<br />

toto) oder weiteren, generalisierenden (totum pro parte) Begriff<br />

(E) PRAGMATISCHE FIGUREN (PRAGMATIC FIGURES)<br />

Apostrophe (apostrophe) Anrufung (und damit Personifikation) eines Dings oder<br />

Abstraktums<br />

Ironie (irony) Aussage, die das Gegenteil der wörtlichen Bedeutung meint<br />

rhetorische Frage (rhetorical question) (Überflüssige) Frage, deren Antwort auch beim Befragten als<br />

selbstverständlich vorausgesetzt wird

Nieragden: ILCS 16<br />

Die Die wichtigsten wichtigsten rhetorischen rhetorischen rhetorischen Figuren Figuren 2 2 2 (Central (Central figures figures of of speech) speech)<br />

EXAMPLES<br />

EXAMPLES<br />

(A) PHONOLOGISCHE FIGUREN (PHONOLOGICAL FIGURES)<br />

Alliteration (alliteration) Love’s Labour’s Lost (Shakespeare)<br />

Assonanz (assonance) mad as a hatter (Lewis Carroll)<br />

Konsonanz (consonance) Having seen all things red/Their eyes are rid (Wilfred Owen)<br />

Onomatopoesie (onomatopoiea) The moa oa oan oa of doves in immemorial elms/And murmuring of<br />

innumerable bee ee ees ee (Alfred Lord Tennyson)<br />

(B) MORPHOLOGISCHE FIGUREN (MORPHOLOGICAL FIGURES)<br />

Anapher (anaphora) Help! Help! I need somebody/Help! Help! Not just anybody/Help! Help! You<br />

know I need someone / Help! (Paul McCartney/John Lennon)<br />

Geminatio (geminatio) Tiger Tiger, Tiger tiger tiger, tiger<br />

burning bright (William Blake)<br />

Epanalepse (epanalepsis) Cassius Cassius from bondage will deliver Cassius Cassius (Julius Caesar)<br />

Epipher (epiphora) Whirl your pointed pines pines/Splash pines your great pines pines (Hilda Doolittle)<br />

Polyptoton (polyptoton) And night doth nightly make grief’s strength seem stronger<br />

(Sonnet 28)<br />

(C) SYNTAKTISCHE FIGUREN (SYNTACTIC FIGURES)<br />

Asyndeton (asyndeton) O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown/The courtier’s, , soldier’s,<br />

, , scholar’s, , , eye, tongue, sword (Hamlet)<br />

Chiasmus (chiasm) Fair Fair is is foul foul, foul and foul foul is fair (Macbeth)<br />

Ellipse (ellipsis) [The] [The] [The] Pub clock [was] five minutes fast. Time [was] going on.<br />

[Its] [Its] Hands [were] moving. [It was] was] Two. [It was] Not yet [two] [two]. [two]<br />

(James Joyce)<br />

Parallelismus (parallelism) O O well well for for for the the the fisherman’s boy/That That he shouts with his sister at<br />

play/O O well well for for the the sailor lad/That That he he sings in his boat on the<br />

bay! (Alfred Lord Tennyson)<br />

Polysyndeton (polysyndeton) When you are old and and grey and and full of sleep (William Butler<br />

Yeats)<br />

Zeugma (zeugma) Time Time and her aunt moved slowly (Jane Austen)<br />

(D) SEMANTISCHE FIGUREN (SEMANTIC FIGURES)<br />

Euphemismus (euphemism) Remember me when I am gone gone away away/Gone away<br />

Gone far far away away away into the the<br />

silent silent land land (Christina Rosetti)<br />

Hendiadyoin (hendiadys) The pitch pitch and and height height of his degree (Richard <strong>II</strong>I)<br />

Katachrese (catachresis) for supple knees knees knees feed feed arrogance (Troilus and Cressida)<br />

Metapher (metaphor) Sometime too hot the eye of heaven heaven [= sun] shines (Sonnet<br />

18)<br />

Metonymie (metonymy) The The crown crown [= the monarchy] will find an heir (The Winter’s<br />

Tale)<br />

Oxymoron (oxymoron) Feather Feather of of lead<br />

lead lead, bright bright smoke<br />

smoke smoke, cold cold fire<br />

fire fire, sick sick sick health health! health (Romeo<br />

and Juliet)<br />

Personifikation (personification) Because I could not stop for Death Death/He Death<br />

He He kindly stopped for me<br />

(Emily Dickinson)<br />

Pleonasmus (pleonasm) They waded through red red blood blood to the knee (Thomas Rymer)<br />

Simile (simile) I wandered lonely lonely as as as a a cloud cloud (William Wordsworth)<br />

Synästhesie (synesthesia) The eye eye of man hath not heard heard, heard<br />

the ear ear of man hath not seen seen<br />

[...] what my dream was (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)<br />

Synekdoche (synecdoche) The western wave wave [= sea] was all aflame (Samuel Coleridge)<br />

(E) PRAGMATISCHE FIGUREN (PRAGMATIC FIGURES)<br />

Apostrophe (apostrophe) O wild West Wind Wind, Wind<br />

thou breath of Autumn’s being (Percy<br />

Bysshe Shelley)<br />

Ironie (irony) For Brutus is an honourable man (Julius Caesar)<br />

rhetorische Frage (rhetorical question) Hath Hath not not a a Jew Jew eyes? eyes? Hath Hath not not a a Jew Jew hands, hands, organs, organs, dimen- dimen<br />

si sions, si<br />

ons, senses, senses, af affections, af fections, passions?<br />

fections, passions? (The Merchant of Venice)

1. 1.4 1. DDrama<br />

D Drama<br />

rama and and Drama Drama Analysis Analysis: Analysis : Key Key Terms<br />

Terms<br />

Nieragden: ILCS 17<br />

The basic insights from drama history and theory presented below can, for the largest<br />

parts, be transferred to other forms of performance-related verbal art as well, i.e. the<br />

musical, the opera and, of course, the movie (s. s. model 2 2 on on on p p 12 above above). above Section 4<br />

can be applied to narrative texts (s. 1.5 below) just as well; section 6 is of special value<br />

to everybody with an interest in structural fim analysis.<br />

1. Elements<br />

dialogue dialogue dialogue A sequence of conversational 'turns' exchanged between two or more speakers or<br />

'interlocutors'. The more specific term duologue is occasionally used to refer to a dialogue<br />

between exactly two speakers.<br />

monologue monologue A long speech in which a character talks to him- or herself. Often, only one<br />

character is on stage during a m., in which case the m. becomes a soliloquy (from Latin<br />

solus, 'alone'). M.s and soliloquies have a number of important dramatic functions: they<br />

foreground the monologist/soliloquist; they provide a transition (or bridge) between scenes;<br />

they open a source of information and exposition; and they let the audience know something<br />

of the private thoughts, motives, and plans of characters.<br />

aside aside A remark that is not heard by the other characters on stage. There are three types of<br />

a.: monological, dialogical, and ad spectatores. A monological a. is a remark that occurs in a<br />

dialogue, but is not meant to be heard by any of the speaker's interlocutors (it is 'monological'<br />

because it is basically a self-communication). A dia dialogical dia<br />

logical logical a. a. in contrast, is a remark that<br />

is addressed to a specific hearer, but is heard by nobody else present (i.e., by nobody but<br />

the intended hearer). Finally, an a. a. ad ad ad ad spectatores<br />

spectatores spectatores<br />

spectatores is addressed directly to the audience and<br />

thus is an important technique of breaking the illusion of the play.<br />

dramatis dramatis personae personae The list of characters. This is an extratextual element usually accompanied<br />

by a brief explicit characterization indicating role, social status, etc. ("JELLABY, a butler,<br />

middle-aged", Stoppard, Arcadia). Often the characters are simply listed in their order of<br />

appearance, but other arrangements are also frequent. For instance, the dramatis personae<br />

may reflect the hierarchy of an aristocratic society, listing the king and his relatives first, then<br />

the dukes and earls, and then the common citizens.<br />

stage stage direction direction A descriptive or narrative passage of secondary text (usually set in italics)<br />

describing the set, scenery, props, costumes, and the nonverbal behavior of the characters<br />

(such as their movements). Ideally, in performance, a s.d. is translated into a property or a<br />

behavioral pattern which is directly perceptible to the audience. Authors' practice in the use<br />

of long or short, narrative or descriptive, strictly prescriptive or merely suggestive stage directions,<br />

varies widely.<br />

irony irony A term with a range of meanings, all of them involving some sort of discrepancy or incongruity.<br />

I. suggests the difference between appearance and reality, between expectation<br />

and fulfillment, the complexity of experience. 1: Verbal <strong>II</strong>.<br />

I<br />

- the opposite is said from what is<br />

intended. / 2: Dramatic <strong>II</strong>.<br />

I<br />

- the contrast between what a character says and what the reader<br />

knows to be true; can be comi comic comi<br />

or tragic tragic. tragic<br />

/ 3: I. of situation - discrepancy between what is<br />

and what would seem appropriate.<br />

2. Types<br />

A play is a plurimedial narrative form designed to be staged in a public performance: it<br />

uses both auditory and visual media: a play's audience has to use their eyes as well as<br />

their ears (a novel, in contrast, is a 'monomedial' form). A play is also a special form of<br />

narrative form because it presents a story.<br />

absolute absolute drama drama A type of drama that does not employ a level of fictional mediation; a play<br />

that makes no use of narrator figures, chorus characters, story-internal stage managers, or<br />

any other 'epic' elements (to be specified in more detail below). The audience witnesses the<br />

action of the play as if it happened 'absolutely', i.e., as if it existed independently of either<br />

author, or narrator, or, in fact, the spectators themselves.<br />

closet closet closet drama drama drama A play that is primarily designed to be read.

Nieragden: ILCS 18<br />

epic epic drama drama drama In contrast to the absolute drama, this is one that has 'epic features' or makes<br />

use of 'epic devices', mainly a narrator figure whose presence creates a distinct, fictional<br />

level of communication complete with addressee, setting, and time line.<br />

tragedy tragedy In Aristotle's definition, t. is the imitation in dramatic form of an action that is serious<br />

and complete, with incidents arousing pity and fear wherewith it effects a catharsis of such<br />

emotions. The language used is pleasurable and throughout appropriate to the situation in<br />

which it is used. The chief characters are noble personages ("better than ourselves," says<br />

Aristotle) and the actions they perform are noble actions..<br />

comedy comedy The essential difference between tragedy and c. is in the depiction of human nature:<br />

tragedy shows greatness in human nature and human freedom whereas c. shows human<br />

weakness and human limitation. The norms of c. are primarily social; the protagonist is<br />

always in a group or emphasizes commonness. A tragic hero possesses overpowering individuality<br />

- so that the play is often named after her/him (Antigone, Othello); the comic protagonist<br />

tends to be a type and the play is often named for the type (The Misanthrope, The<br />

Alchemist, The Brute). Plausibility is not usually the central characteristic (cause-effect progression)<br />

but coincidences, improbable disguises, mistaken identities make up the plot. The<br />

purpose of c. is to make us laugh and at the same time, help to illuminate human nature and<br />

human weaknesses. Conventionally, comedies have a happy ending. Accidental discovery,<br />

acts of divine intervention (deus deus ex ex machina machina), machina or sudden reforms are common devices.<br />

3. 'People'<br />

character character Not a real-life person but only a 'paper being', a being created by an author and<br />

existing only within a fictional text, usually on the level of action. Example: the character<br />

Hamlet in the play Hamlet by Shakespeare.<br />

flat/round flat/round character character A f.c. is known by one or two traits, and remains static from the beginning<br />

of the plot to the end. A r.c. is complex with many features and dynamic, i.e. undergoes<br />

permanent change. To be credible, this change must be within the possibilities of the character,<br />

sufficiently motivated, and allowed sufficient time for change.<br />

protagonist/antagonist protagonist/antagonist The p. is the central character, sympathetic or unsympathetic. The<br />

forces working against her/him, whether persons, things, conventions of society, or traits of<br />

their own character, are the as.<br />

stock stock character character character A stereotyped, conventionalized character type whom the audience recognizes<br />

immediately (e.g. the country bumpkin, the absent-minded professor, the mad scientist,<br />

the cruel mother-in-law, the heartless banker, the shrewish wife)<br />

4. Characterisation (adapted from Manfred Pfister. 1988. The Theory and Analysis of Drama. Cambridge: CUP [orig<br />

1977: Das Drama. Theorie und Analyse. München: Fink])<br />

The most relevant characterisation techniques are:<br />

AUTHORIAL<br />

AUTHORIAL AUTHORIAL<br />

FIGURAL<br />

FIGURAL<br />

EXPLICIT EXPLICIT description in secondary text /<br />

telling names<br />

IMPLICIT IMPLICIT correspondence and contrast relations<br />

auto-commentary /<br />

altero-commentary<br />

NON NON-VERBAL<br />

NON VERBAL VERBAL: VERBAL physiognomy; facial expression;<br />

gestures; masks & costume;<br />

properties; setting; behaviour<br />

VERBAL VERBAL: VERBAL voice; dialect; sociolect; idiolect;<br />

jargon; register; style<br />

5. Action<br />

action action The sum of events (or action units) occurring on a play's level of action. Sometimes it<br />

is possible to distinguish the 'primary story line' from other 'external' events that take place<br />

before the beginning or after the end of the play.<br />

point point of of attack attack The event chosen to begin the play's action. There are three main options: (i)<br />

a play beginning at an 'early' p.o.a. or ab ab ovo ovo (literally, 'from the egg') typically begins with a<br />

state of equilibrium or non-conflict; (ii) for a beginning medias medias medias in in in res res ('in the midst of things'),<br />

the p.o.a. is set close to the climax of the action; and (iii) for a beginning ultimas in res ('with<br />

the last event'), the p.o.a. occurs after the climax and near the end.

Nieragden: ILCS 19<br />

unity unity of of time, time, place, place, and and action action ("the ("the unities") unities") Aristotelian 'presciption' of limiting the time,<br />

place, and action of a play to a single spot and a single action over the period of 24 hours<br />

6. Structure (following the classic Technique of the Drama (1863) by Gustav Freytag).<br />

In the traditional five-act tragedy (as established by Horace 50 BC), we tend to meet a recurrent<br />

organization of moments in the plot:<br />

EXPOSITION EXPOSITION The introduction of time, place, characters and background of the play's action.<br />