Fitness effects of inbreeding and outbreeding on golden paintbrush ...

Fitness effects of inbreeding and outbreeding on golden paintbrush ...

Fitness effects of inbreeding and outbreeding on golden paintbrush ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fitness</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong> (Castilleja levisecta):<br />

Implicati<strong>on</strong>s for recovery <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> reintroducti<strong>on</strong><br />

September 2003<br />

Thomas N. Kaye<br />

Beth Lawrence<br />

Institute for Applied Ecology<br />

Corvallis, Oreg<strong>on</strong><br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Resources<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Institute for Applied Ecology

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

PREFACE<br />

This report is the result research c<strong>on</strong>ducted by the Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE) under c<strong>on</strong>tract<br />

with a public agency, the Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Resources, Natural heritage Program<br />

under C<strong>on</strong>tract No. 03-218. IAE is a n<strong>on</strong>-pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>it organizati<strong>on</strong> dedicated to natural resource c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

research, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong>. Our aim is to provide a service to public <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> private agencies <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals<br />

by developing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> communicating informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> ecosystems, species, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> effective management<br />

strategies <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> by c<strong>on</strong>ducting research, m<strong>on</strong>itoring, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> experiments. IAE <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fers educati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

opportunities through 3-4 m<strong>on</strong>th internships. Our current activities are c<strong>on</strong>centrated <strong>on</strong> rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

endangered plants, habitat management <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> invasive species.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Questi<strong>on</strong>s regarding this report or IAE should be directed to:<br />

Thomas N. Kaye<br />

Institute for Applied Ecology<br />

227 SW 6 th<br />

Corvallis, Oreg<strong>on</strong> 97333<br />

ph<strong>on</strong>e: 541-753-3099<br />

fax: 541-753-3098<br />

Funding for this project was provided by the Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Resources<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Institute for Applied Ecology. We thank the Oreg<strong>on</strong> State University Seed Lab <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Dale<br />

Brown for providing germinati<strong>on</strong> assistance <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> facilities used in this study. We also thank<br />

Melissa Carr, Emerin Hatfield, Rebecca Kessler, Melanie Barnes, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Angela Br<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>t<br />

(IAE/Native Plant Society <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Oreg<strong>on</strong> Interns) for assistance with plant propagati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> data<br />

collecti<strong>on</strong>. Manuela Huso provided generous <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> invaluable statistical support <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> assistance.<br />

We thank Florence Caplow <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Carla Wise for their discussi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> comments <strong>on</strong> an earlier<br />

draft <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this report.<br />

i

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Preface i<br />

Acknowledgments i<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong> 1<br />

Background 1<br />

The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mating system: <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1<br />

Methods 4<br />

Pollinati<strong>on</strong> experiment 4<br />

Propagati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crossed progeny 6<br />

Analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fitness measures 6<br />

Results 8<br />

Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> fitness 8<br />

Discussi<strong>on</strong> 11<br />

Mating system <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta 11<br />

Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> fitness 11<br />

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for recovery <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> reintroducti<strong>on</strong> 14<br />

Literature cited 16<br />

ii

INTRODUCTION<br />

Background<br />

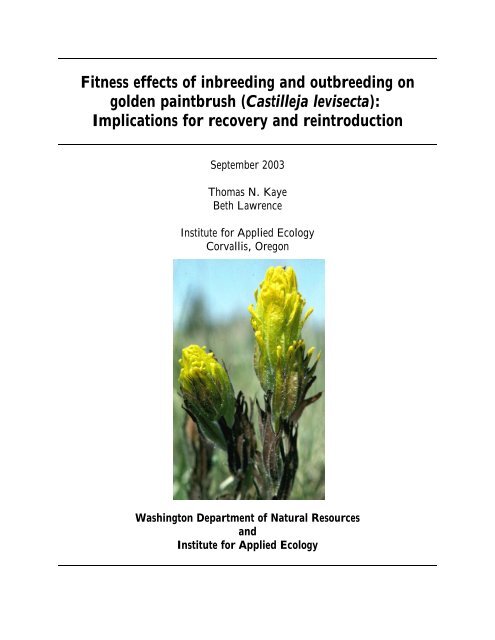

Castilleja levisecta (<strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong>)<br />

<strong>on</strong>ce occupied prairies <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grassl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

throughout the Puget Trough <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Willamette Valley. Habitat destructi<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> alterati<strong>on</strong> over the past century have<br />

resulted in substantial declines in native<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> in this ecoregi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> several<br />

species, including <strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong>, are<br />

now listed by state <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> federal agencies as<br />

threatened or endangered. All remaining<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong> occur in<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

Figure 1. Castilleja levisecta (<strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong>).<br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> British Columbia; the species is c<strong>on</strong>sidered to be extirpated in Oreg<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Castilleja levisecta is an herbaceous perennial that appears to reproduce <strong>on</strong>ly by seed. Many<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s are declining, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> past research indicates that disturbances such as fire <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

mowing may be useful for maintaining or exp<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing existing populati<strong>on</strong>s (USFWS 2000).<br />

Like most <strong>paintbrush</strong>es (Heckard 1962), this species is a hemiparasite – its roots penetrate the<br />

roots <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> neighboring plant species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> derive nutrients, carbohydrates, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> possibly other<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>dary compounds from these hosts.<br />

The Recovery Plan for <strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong> (USFWS 2000) identifies populati<strong>on</strong> reintroducti<strong>on</strong>,<br />

development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> propagati<strong>on</strong> methods, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the pollinati<strong>on</strong> biology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the species as<br />

high priority acti<strong>on</strong>s to meet recovery objectives. Because no populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this species are<br />

known to remain in Oreg<strong>on</strong>, populati<strong>on</strong> reintroducti<strong>on</strong> will be crucial to recovery in this regi<strong>on</strong><br />

as well as porti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the range to the north.<br />

1

The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mating system: <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Creating new populati<strong>on</strong>s from propagated material should c<strong>on</strong>sider the source <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these<br />

materials as well as their genetic relati<strong>on</strong>ship to <strong>on</strong>e another. When plants self or mate with<br />

close relatives their <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring may show negative <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> related to <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong>. On<br />

the other h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, individuals that are distantly related may produce <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring that show higher<br />

fitness than either parent, or their <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring can have reduced vigor due to <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> (see reviews by Kaye 2001a <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hufford <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mazer 2003). The reintroducti<strong>on</strong><br />

plan for C. levisecta (Caplow 2002) recommends that the risks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> be examined experimentally.<br />

Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> – Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> occurs when close relatives mate (or plants<br />

self-fertilize) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring display reduced vigor or fitness. Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> is a<br />

well-known <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> studied phenomen<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten occurs in small, fragmented, or isolated<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s, or when mating is frequent between close neighbors. It may result when<br />

deleterious recessive alleles are paired (creating homozygotes) so that their negative <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> are<br />

expressed in the progeny. When these genes are not paired (as after outcrossing), they may be<br />

masked by a more favorable allele (as a heterozygote), so the progeny functi<strong>on</strong> normally.<br />

Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> may also result from loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> heterozygote advantage. In plants,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> can be expressed at any stage in the life cycle, including seed<br />

germinati<strong>on</strong>, seedling establishment, plant growth rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> survival, flowering, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed<br />

producti<strong>on</strong>. Populati<strong>on</strong>s suffering from <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> can <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten benefit from<br />

out-crossing with individuals in other populati<strong>on</strong>s, which may result in higher heterozygosity,<br />

improved health <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> greater populati<strong>on</strong> viability. This is <strong>on</strong>e factor used to<br />

support the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> multiple sources <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant materials in restorati<strong>on</strong> (<strong>on</strong>e side <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Single or<br />

Multiple Source debate [Kaye 2001a]).<br />

Outbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> – Outbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong>, which is a reducti<strong>on</strong> in fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> progeny<br />

from distant parents, has a much shorter history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> study <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is less documented <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

understood than <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong>. A recent literature search (Kaye 2001a) found 468<br />

papers <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> but <strong>on</strong>ly 25 references to <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong>. Even so,<br />

this hot topic in genetic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> research has been dem<strong>on</strong>strated in various organisms,<br />

including salm<strong>on</strong> (Gharrett 1999), fruit flies (Aspi 2000), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> chimpanzees (Morin et al.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

2

1992). Some animal studies have found a positive effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g>, however, such as in<br />

bats (Rossiter et al. 2001). Am<strong>on</strong>g plants it may occur in larkspur (Waser <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Price 1991,<br />

1994), skyrocket (Waser et al. 2000), a carnivorous pitcher plant (Sheridan <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Karowe<br />

2000), Hawaiian silversword (Friar et al. 2001), a Mediterranean borage (Quilichini et al.<br />

2001), a subshrub (M<strong>on</strong>talvo <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ellstr<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2001), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> an exotic roadside weed (Keller et al.<br />

2000). In many cases, crossing between unrelated individuals results in F1 progeny with<br />

increased fitness, followed by the expressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> in later generati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(Hufford <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mazer 2003). Most researchers (e.g., Lynch 1991, Waser 1993) believe that<br />

there is hybrid vigor in the first generati<strong>on</strong> followed by reduced fitness in later generati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

from loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecological adaptati<strong>on</strong> (at least <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the original parents was poorly adapted to<br />

the site) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>/or disrupti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> coadapted gene complexes.<br />

In this paper we examine the mating system <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> explore the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> F1 progeny fitness at multiple life history stages. The results<br />

have direct bearing <strong>on</strong> reintroducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> recovery acti<strong>on</strong>s for the species because the risks<br />

associated with <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> need to be identified in order to assist with seed<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> outplanting activities.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

3

METHODS<br />

Pollinati<strong>on</strong> experiment<br />

We performed c<strong>on</strong>trolled cross-pollinati<strong>on</strong> between<br />

individuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> differing known heritage. These crosses were<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> four major types: self-pollinati<strong>on</strong>, crosses between<br />

siblings, crosses between n<strong>on</strong>-sibling plants from the same<br />

source populati<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> crosses between individuals from<br />

different populati<strong>on</strong>s. The plants used in these crosses were<br />

grown in pots from seed collected in wild populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong><br />

Whidbey Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> San Juan Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Washingt<strong>on</strong> in<br />

September, 2000. Sources <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plants <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each<br />

type <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cross are listed in Table 1. Genetic identities am<strong>on</strong>g<br />

the three source sites (False Bay [San Juan Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>], West<br />

Beach, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fort Casey [Whidbey Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>]) were all very high<br />

(0.93-0.94, Godt <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hamrick [2002]) although their<br />

geographic distances ranged from 13.3 to 45.4 km (Table 1).<br />

Seeds from individual plants were kept separate at the time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

collecti<strong>on</strong>, so that maternal lines could be documented.<br />

Crosses between siblings involved pollinati<strong>on</strong> between two<br />

plants grown from seed taken from the same maternal parent.<br />

Flowers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta are borne <strong>on</strong> a raceme, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

each flower has <strong>on</strong>e pistil <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> stigma as well as a single<br />

ovary with numerous ovules. The mean number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ovules<br />

per flower in C. levisecta is 183 ± 5.8 (Kaye, unpubl. data).<br />

Each fruit is a capsule <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the seeds are typically very small<br />

(~0.5 mm). The flowers are protogynous; their pistils<br />

extend bey<strong>on</strong>d the opening <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the flower <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the stigma<br />

becomes receptive prior to anther dehiscence (Figure 2). We<br />

grew all plants in a screen house to prevent insects from<br />

visiting the experimental flowers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> moving pollen between<br />

plants.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

Figure 2. The inflorescence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Castilleja levisecta is a raceme, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the individual flowers arepartly<br />

covered by a showy yellow bract<br />

(shown here pulled back to expose a<br />

flower). The receptive stigmas can be<br />

seen as two-lobed, rounded structures<br />

emerging above the flowers.<br />

Figure 3. Pollinated flowers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> C.<br />

levisecta were marked with colorcoded<br />

thread.<br />

4

To prevent unwanted self-pollinati<strong>on</strong>, all crosses first involved emasculati<strong>on</strong>, i.e., removing<br />

the anthers from the flowers identified as pollen recipients (dames) prior to anther dehiscence.<br />

We then used forceps to remove a mature, dehiscing anther from a pollen d<strong>on</strong>or plant (sire)<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> applied pollen directly to the stigma <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the dame. Each dame flower <strong>on</strong> a raceme was<br />

marked with color coded thread tied around its base (Figure 3).<br />

When fruits matured, they were removed from the dames <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> returned to the lab for<br />

examinati<strong>on</strong> under a dissecting microscope. Each fruit was measured for length <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> width,<br />

then opened to count normally developed seeds as well as undeveloped ovules. We used this<br />

informati<strong>on</strong> to calculate the proporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total ovules that set seed.<br />

Table 1. Crossing types, source populati<strong>on</strong>s involved, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample sizes (number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crosses<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted). Geographic distances between populati<strong>on</strong>s are given in parentheses.<br />

Cross type source populati<strong>on</strong>s used sample size<br />

self Fort Casey<br />

West Beach<br />

sibling False Bay<br />

West Beach<br />

within-populati<strong>on</strong> False Bay<br />

Fort Casey<br />

West Beach<br />

between-populati<strong>on</strong> False Bay × Fort Casey (45.4 km)<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

False Bay × West Beach (33.1 km)<br />

Fort Casey × West Beach (13.3 km)<br />

2<br />

17<br />

Total=19<br />

3<br />

9<br />

Total=12<br />

5<br />

7<br />

23<br />

Total=35<br />

6<br />

9<br />

12<br />

Total=27<br />

5

Propagati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crossed progeny<br />

To germinate seeds from each cross, the seeds were placed <strong>on</strong> germinati<strong>on</strong> pads moistened<br />

with distilled water in individual plastic boxes with tight fitting lids. We used 50 seeds from<br />

each cross except where fewer were available. The seeds were then exposed to cool<br />

temperatures (4 °C) for six weeks, followed by alternating warm temperatures (15 °C <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 25<br />

°C) for two weeks. This method has resulted in high germinati<strong>on</strong> rates (generally >75%),<br />

depending <strong>on</strong> source populati<strong>on</strong>) in previous studies with C. levisecta (Wentworth 1998, Kaye<br />

2001b). After these treatments we counted the total number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seedlings emerging in each<br />

box.<br />

Up to ten seedlings from each cross were then planted in fine potting soil in 5 x 5 cm by 6 cm<br />

deep pots in a greenhouse. The plants were watered from beneath by flooding the greenhouse<br />

bench for 30 minutes, twice per week. After 4 weeks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> growth, the small plants were then<br />

repotted into 10 x 10 cm by 9 cm deep pots with a seedling <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Eriophyllum lanatum, an<br />

herbaceous plant in the Asteraceae that proved to be a superior host in earlier propagati<strong>on</strong><br />

experiments with C. levisecta (Kaye 2001b). The potted plants were then moved out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> doors<br />

to a flat garden bed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> allowed to grow an additi<strong>on</strong>al 8 weeks. All plants were fertilized <strong>on</strong>ce<br />

per week throughout this period. The total growth period from first potting to the end <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

experiment was 89 days (ending 30 June 2003). We measured plant size <strong>on</strong> the 89 th day as<br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stems, length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each stem, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> flowering racemes.<br />

Analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fitness measures (seed set, seed germinati<strong>on</strong>, plant growth, flowering)<br />

To determine the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crossing distance <strong>on</strong> fitness in Castilleja levisecta, we performed<br />

separate statistical analyses <strong>on</strong> each measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant performance we observed (Table 2). We<br />

tested the hypothesis that pollinati<strong>on</strong>-type had no effect <strong>on</strong> seed set with a Kruskal-Wallis<br />

<strong>on</strong>e-way ANOVA <strong>on</strong> ranks combined with Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparis<strong>on</strong> Z-value tests<br />

to compare individual treatments. These n<strong>on</strong>-parametric tests were used because the seed-set<br />

data, especially residuals for sibling crosses, did not c<strong>on</strong>form to the assumpti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> normal<br />

distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> equal variances required for st<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard ANOVA. We examined seed<br />

germinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> flowering with logistic regressi<strong>on</strong> to determine if the odds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> germinati<strong>on</strong> or<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

6

flowering differed am<strong>on</strong>g the treatments. Our examinati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these data suggested that their<br />

distributi<strong>on</strong>s were not strictly binary, so we used quasi-likelihood methods. And finally, we<br />

used <strong>on</strong>e-way ANOVA to test for a treatment effect <strong>on</strong> plant growth expressed as the sum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

all stem lengths <strong>on</strong> each plant, followed by Fisher’s protected LSD multiple-comparis<strong>on</strong> test to<br />

compare individual treatments.<br />

Table 2. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fitness</str<strong>on</strong>g> measures used to evaluate the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

Castilleja levisecta, the statistical analysis implemented in this study, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample sizes for each<br />

treatment.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fitness</str<strong>on</strong>g> measure (resp<strong>on</strong>se variable) Statistical analysis<br />

Seed set (proporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ovules developing<br />

into normal seeds)<br />

Seed germinati<strong>on</strong> (odds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seeds<br />

germinating)<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

Kruskal-Wallis <strong>on</strong>e-way ANOVA <strong>on</strong> ranks<br />

with Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparis<strong>on</strong><br />

Z-value test. Sample sizes: self=19,<br />

sibling=12, same populati<strong>on</strong>=35, different<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>=27.<br />

Logistic regressi<strong>on</strong>, quasi-likelihood.<br />

Sample sizes: self=8, sibling=10, same<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>=35, different populati<strong>on</strong>=26.<br />

Plant growth (total stem length) One-way ANOVA, Fisher’s protected LSD<br />

Flowering (odds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> producing a flowering<br />

stem)<br />

multiple-comparis<strong>on</strong> test. Sample sizes:<br />

self=6, sibling=9, same populati<strong>on</strong>=35,<br />

different populati<strong>on</strong>=25.<br />

Logistic regressi<strong>on</strong>, quasi-likelihood.<br />

Sample sizes: self=6, sibling=9, same<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>=35, different populati<strong>on</strong>=25.<br />

7

RESULTS<br />

Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> fitness<br />

Seed set – Castilleja levisecta appears to be almost completely self-incompatible, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed-set<br />

appears to increase as the genetic relati<strong>on</strong>ship am<strong>on</strong>g mating individuals becomes more distant.<br />

The proporti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ovules that set normal seeds was significantly affected by pollinati<strong>on</strong> cross-<br />

type in Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (df=3, P 2 corrected for ties=44.3, P

Seed germinati<strong>on</strong> – We found no evidence that seed germinati<strong>on</strong> was affected by cross type.<br />

Logistic regressi<strong>on</strong> did not detect any significant difference in germinati<strong>on</strong> rate am<strong>on</strong>g the<br />

mating types tested here (df=3,75; P 2 =0.32; P=0.957). The overall seed germinati<strong>on</strong> rate<br />

averaged 84.5% ± 3% (SE). Note that few seeds were produced from self <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sibling<br />

crosses, so that little statistical power was available to detect differences between these matings<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> other types. This rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> germinati<strong>on</strong> is typical <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild-collected seeds, which tend to have<br />

greater than 75% germinati<strong>on</strong> (Kaye 2001b) under the same envir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s as<br />

applied in the current study.<br />

Plant Growth – Plant size was affected substantially by mating type (df=3,71; F=0.12.72;<br />

P

Flowering – The rate at which plants flowered was also significantly different am<strong>on</strong>g plants<br />

from different cross-types (logistic regressi<strong>on</strong>; df=3,71; P 2 =8.77; P=0.033). On average,<br />

11% (±3% SE) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crosses between n<strong>on</strong>-sibling individuals from the same populati<strong>on</strong> produced<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring that flowered (Figure 6), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> the odds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these plants flowering was not significantly<br />

different from self or sibling crosses. However, the odds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> flowering for plants from crosses<br />

between different populati<strong>on</strong>s was 1.1 to 4.6 times higher than within populati<strong>on</strong> crosses.<br />

flowering rate<br />

30%<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

self sibling same populati<strong>on</strong> different populati<strong>on</strong><br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

pollen source<br />

Figure 6. Mean (±1 SE) percentage flowering <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> F1 plants from different cross types.<br />

10

DISCUSSION<br />

Mating system <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta<br />

Castilleja levisecta appears to require out-crossing for reliable seed set because the species<br />

possesses barriers to self-fertilizati<strong>on</strong>. These barriers include protogyny in the flowers which<br />

may prohibit self-pollinati<strong>on</strong> in the field (but possibly not geit<strong>on</strong>ogamy by insects), as well as<br />

genetic or physiological self-incompatibility. Although the mechanism <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> self-incompatibility<br />

is unknown, it appears to block seed set almost completely, with the excepti<strong>on</strong> that a small<br />

number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seeds may be produced in fruits from self-pollinati<strong>on</strong>s. We found that am<strong>on</strong>g 19<br />

selfings, <strong>on</strong>ly 8 produced fruits with any filled seeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> these seeds generally numbered <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

1 or 2, while in outcrossed plants fruits c<strong>on</strong>taining seeds were produced from all pollinati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Self-incompatibility may be typical in the genus Castilleja. Although we found no published<br />

studies that specifically address compatibility within species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this genus, Heckard (1968), in<br />

his extensive study <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> polyploidy in Castilleja, stated that most species appear to be self-sterile<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> no seed is produced unless pollinators are present.<br />

Many species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plants maintain a mixed-mating system in which both self- <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cross-<br />

pollinati<strong>on</strong> serve to fertilize embryos. However, because Castilleja levisecta is nearly self-<br />

incompatible, the vast majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seeds produced in its populati<strong>on</strong>s are likely from insect-<br />

mediated crosses between different individuals. This predicti<strong>on</strong> is c<strong>on</strong>sistent with findings<br />

from a recent genetic study (Godt <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hamrick 2001) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> allozyme diversity in C. levisecta,<br />

which found no evidence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in its populati<strong>on</strong>s. The authors also noted that there<br />

could be str<strong>on</strong>g selecti<strong>on</strong> against inbred individuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> our measurements <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fitness traits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

inbred plants support this assumpti<strong>on</strong>. In additi<strong>on</strong>, heterozygosity is generally higher than<br />

expected in populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> C. levisecta (Godt <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hamrick 2001), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> self-incompatibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

failure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> flowering in inbred individuals could have c<strong>on</strong>tributed to this.<br />

Effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> fitness<br />

We found evidence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crossing distance <strong>on</strong> fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta at multiple<br />

stages in the life cycle <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the species. Both <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> advantage<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

11

(hybrid vigor) were detected. For example,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g>, including selfing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

am<strong>on</strong>g siblings (which, <strong>on</strong> average, share 50%<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their alleles), reduced seed producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

plant growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the F1 generati<strong>on</strong> significantly<br />

when compared to crosses between n<strong>on</strong>-siblings<br />

from the same or different populati<strong>on</strong>s (Figures<br />

4, 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 7). Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> was not<br />

detected in seed germinati<strong>on</strong> or flowering rate,<br />

but this may be because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> insufficient statistical<br />

power due to the small sample sizes available<br />

for the inbred treatments.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

Figure 7. Castilleja levisecta individuals (30 days<br />

old) from self-pollinati<strong>on</strong> (left) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

(right).<br />

One recent example <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> (Richards 2000) in a perennial plant, white<br />

campi<strong>on</strong> (Silene alba), showed that isolated populati<strong>on</strong>s had high <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> (in the<br />

form <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> low seed germinati<strong>on</strong> success), crosses between related individuals resulted in reduced<br />

germinati<strong>on</strong> success, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> gene-flow was higher between unrelated individuals. This study is<br />

important because it dem<strong>on</strong>strates the potential for a “rescue-effect” for populati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

experiencing <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> by intenti<strong>on</strong>ally mixing unrelated individuals into such a<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>. Although <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> has not been detected in Castilleja levisecta populati<strong>on</strong>s to<br />

date (Godt <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hamrick 2002), small populati<strong>on</strong>s could experience a decline in seed<br />

producti<strong>on</strong> due to insufficient numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetically compatible individuals. In additi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> could accumulate in very small populati<strong>on</strong>s in which the surviving<br />

members are genetically related. In either case, intenti<strong>on</strong>ally introducing pollen or individual<br />

plants from other populati<strong>on</strong>s (preferably nearby sites) could improve seed producti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> play<br />

a role in populati<strong>on</strong> recovery.<br />

Outbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> was not detected at any level in our study <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed set <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> F1 plant<br />

traits. Instead, we found significant increases in fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plants produced by crosses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

individuals from different populati<strong>on</strong>s. In particular, plant growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> flowering rate were<br />

substantially higher in outbred plants (Figures 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6). Crosses between plants from different<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s produced F1 individuals that produced 25% more stem length, <strong>on</strong> average, than<br />

12

plants from within-populati<strong>on</strong> crosses. Further, flowering was 1.1 to 4.6 times more likely in<br />

outbred plants than those from within populati<strong>on</strong> matings.<br />

One c<strong>on</strong>cern about this study is that multiple populati<strong>on</strong>s were used for each treatment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

pooled for analysis. For example, sibling crosses involved two different source populati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> their relative decline in fitness might best be compared <strong>on</strong>ly to their parents or other plants<br />

from the same populati<strong>on</strong>. One reas<strong>on</strong> for this c<strong>on</strong>cern is that differences in heterozygosity<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g populati<strong>on</strong>s could affect the severity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> detected in sibling<br />

crosses. However, we believe that our analysis with pooled data is justified because the levels<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> heterozygosity in these populati<strong>on</strong>s were similar (<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> high, 0.174 at West Beach <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 0.231<br />

at False Bay; Godt <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hamrick 2002). In additi<strong>on</strong>, measurements <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> parental<br />

plants <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all crosses detected no significant differences in stem producti<strong>on</strong> or flowering (Kaye,<br />

unpubl. data). Another c<strong>on</strong>cern is that the crosses between populati<strong>on</strong>s to detect <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> could differ if the various pairs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s crossed differed in their genetic<br />

similarity. For example, a between-populati<strong>on</strong> cross between two populati<strong>on</strong>s that were<br />

similar genetically might result in a different effect than a cross between two genetically<br />

distant populati<strong>on</strong>s. The pairs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong>s used for crosses in our study all had high <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

similar genetic identities (0.93 - 0.94, Hamrick <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Godt 2002), despite variability in their<br />

geographic distances (Table 2).<br />

Although we did not detect <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> in the F1 generati<strong>on</strong>, this phenomen<strong>on</strong> may<br />

yet act in Castilleja levisecta. Several studies (reviewed in Kaye 2001a <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Hufford <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Mazer 2003) have found that expressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> may be delayed to the F2<br />

or F3 generati<strong>on</strong>s. Even so, it may not occur at all, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> some studies have found no risk <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> even for very l<strong>on</strong>g-distance crosses. For example, in a study <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata, an annual legume) Fenster <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Galloway (2000)<br />

collected plants from various populati<strong>on</strong>s ranging from 100 m to 1000 km apart, performed<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trolled crosses, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grew the parents <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> progeny in comm<strong>on</strong> gardens. They found that<br />

first-generati<strong>on</strong> hybrids between plants from different populati<strong>on</strong>s outperformed their parents,<br />

regardless <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the geographic distance between sources. By the third generati<strong>on</strong>, however, this<br />

increase in fitness declined. The level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline varied with distance between parent<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s, with crosses between plants from

plants at least as vigorous as their original parents. Thus, crosses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> up to 1000 km had a<br />

short-term beneficial effect, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> little l<strong>on</strong>g-term risk (at least through the third generati<strong>on</strong>).<br />

There have been too few studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> out-breeding depressi<strong>on</strong> to make generalizati<strong>on</strong>s about the<br />

level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> risk, however. Some studies have documented negative <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> across<br />

short distances (tens <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> meters to 100 m) (Price <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Waser 1979, Waser <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Price 1989, 1991,<br />

1994) or between different habitats (M<strong>on</strong>talvo <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ellstr<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2001), while others have found<br />

great variability in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g>, even in the same species (e.g., Waser et al.<br />

2000). The threat <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> is <strong>on</strong>e argument against mixing seed sources<br />

during plant restorati<strong>on</strong> (Kaye 2001a). It is also <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the dangers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> moving plants a great<br />

distance to a restorati<strong>on</strong> area where they could interbreed with a local populati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Outbreeding advantage may play a role in the formati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> new species through hybridizati<strong>on</strong><br />

in Castilleja, which is a process that has been documented in the genus (Heckard 1962),<br />

especially in the Intermountain West (Heckard <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Chuang 1977). In additi<strong>on</strong>, the presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

hybrid swarms in mixed species populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja may be facilitated by the lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

inter-specific mating barriers (Anders<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Taylor 1983) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> hybrid vigor <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mixed species<br />

crosses.<br />

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for recovery <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> reintroducti<strong>on</strong><br />

1. If seed producti<strong>on</strong> is found to be low in any small, wild populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja<br />

levisecta, the intenti<strong>on</strong>al importati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pollen or transplanted individuals should be<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sidered to restore compatible mating types (or genetically unrelated individuals) to<br />

the populati<strong>on</strong>. This potential recovery acti<strong>on</strong> should be evaluated al<strong>on</strong>g with other<br />

explanati<strong>on</strong>s for low seed producti<strong>on</strong>, including insufficient pollinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> resource<br />

limitati<strong>on</strong> (due to climatic <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g>, interspecific competiti<strong>on</strong>, or other factors).<br />

2. Seed collecti<strong>on</strong> for reintroducti<strong>on</strong> projects should be managed to spread collecti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g many individuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> emphasize n<strong>on</strong>-neighbors, if possible. Neighboring plants<br />

may be more genetically related than distant plants in the same populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> more<br />

likely to cross-pollinate with each other, thus increasing the potential for <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

14

depressi<strong>on</strong>. In additi<strong>on</strong>, seeds from different individual plants should be stored<br />

separately.<br />

3. Reintroducti<strong>on</strong> projects should c<strong>on</strong>sider the genetic relati<strong>on</strong>ship <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals in<br />

founder populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> take steps to minimize the chances that members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the new<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> are siblings or close relatives. Specifically, n<strong>on</strong>-relatives should be planted<br />

close to <strong>on</strong>e another <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> relatives should be kept distant.<br />

4. Mixing plants from different source populati<strong>on</strong>s at reintroducti<strong>on</strong> sites may improve the<br />

fitness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their progeny, at least in the short term. At this time, this recommendati<strong>on</strong><br />

should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>on</strong>ly for adjacent populati<strong>on</strong>s in regi<strong>on</strong>s where the species is still<br />

extant (e.g., Whidbey Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> or San Juan Isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> when there is some suggesti<strong>on</strong><br />

that the populati<strong>on</strong> is declining or is already very small, or in areas where the species<br />

has been extirpated (such as the Willamette Valley) so that any risks <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> local genetic c<strong>on</strong>taminati<strong>on</strong> are minimized.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

15

LITERATURE CITED<br />

Anders<strong>on</strong>, A.V.R. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> R.J. Taylor. 1983. Patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> morphological variati<strong>on</strong> in a populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

mixed species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja (Scrophulariaceae). Systematic Botany 8:225-232.<br />

Aspi, J. 2000. Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> in male courtship s<strong>on</strong>g characters in<br />

Drosophila m<strong>on</strong>tana. Heredity 84:273-282.<br />

Caplow, F. 2002. Reintroducti<strong>on</strong> plan for Castilleja levisecta (<strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong>).<br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong> Natural Heritage Program, Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Resources,<br />

Olympia, Washingt<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Fenster, C.B. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> L.F. Galloway. 2000. Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> in natural<br />

populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Chamaecrista fasciculata (Fabaceae). C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Biology<br />

14:1406-1412.<br />

Friar, E.A., D.L. Boose, T. Ladoux, E.H. Roals<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> R.H. Robichaux. 2001. Populati<strong>on</strong><br />

structure in the endangered Mauna Loa silversword, Argyroxiphium kauensis<br />

(Asteraceae), <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> its bearing <strong>on</strong> reintroducti<strong>on</strong>. Molecular Ecology 10:1153-1164.<br />

Gharrett, A.J. 1999. Outbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> between odd-<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> even-broodyear pink salm<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Aquaculture 173:117-129.<br />

Godt, M.J.W. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> J.L. Hamrick. 2002. Allozyme diversity in the federally threatened <strong>golden</strong><br />

<strong>paintbrush</strong>, Castilleja levisecta (Scrophulariaceae). Unpublished report from the<br />

University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Georgia, Athens, Georgia to the Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural<br />

Resources, Olympia, Washingt<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Guerrant, E.O., Jr. 2003. Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for the reintroducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Castilleja levisecta based<br />

<strong>on</strong> patterns <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic diversity as revealed by allozyme data. Unpublished report from the<br />

Berry Botanic Garden, Portl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Oreg<strong>on</strong> to the Washingt<strong>on</strong> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural<br />

Resources, Olympia, Washingt<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

16

Heckard, L.R. 1962. Root parasitism in Castilleja. Botanical Gazette 124:21-29<br />

Heckard, L.R. 1968. Chromosome numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> polyploidy in Castilleja (Scrophulariaceae).<br />

Britt<strong>on</strong>ia 20:212-226.<br />

Heckard, L.R. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> T.-I. Chuang. 1977. Chromosome numbers, polyploidy, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> hybridizati<strong>on</strong> in<br />

Castilleja (Scrophulariaceae) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Great Basin <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rocky Mountains. Britt<strong>on</strong>ia 29:159-<br />

172.<br />

Hufford, K.M. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> S.J. Mazer. 2003. Plant ecotypes: genetic differentiati<strong>on</strong> in the age <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

ecological restorati<strong>on</strong>. Trends in Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Evoluti<strong>on</strong> 18:147-155.<br />

Kaye, T.N. 2001a. Comm<strong>on</strong> ground <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>troversy in native plant restorati<strong>on</strong>: the SOMS<br />

debate, source distance, plant selecti<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a restorati<strong>on</strong>-oriented definiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> native.<br />

In, Native Plant Propagati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Restorati<strong>on</strong> Strategies. R. Rose <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> D. Haase, editors.<br />

Nursery Technology Cooperative <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Western Forestry <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Associati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Corvallis, Oreg<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Kaye, T.N. 2001b. Restorati<strong>on</strong> research for <strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong> (Castilleja levisecta), a<br />

threatened species. Institute for Applied Ecology, Corvallis, Oreg<strong>on</strong>. Available <strong>on</strong>line at<br />

http://www.appliedeco.org/Reports/Cale_research.PDF.<br />

Keller, M., J. Kollmann <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> P.J. Edwards. 2000. Genetic introgressi<strong>on</strong> from distant<br />

provenance reduces fitness in local weed populati<strong>on</strong>s. Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Applied Ecology<br />

37(4): 647-659.<br />

Lynch, M. 1991. The genetic interpretati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Evoluti<strong>on</strong> 45:622-629.<br />

Meffe, G.K. 1996. Genetic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> eco-logical guidelines for species re-introducti<strong>on</strong> programs.<br />

Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Great Lakes Research 21:3-9.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

17

M<strong>on</strong>talvo, A.M. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> N.C. Ellstr<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>. 2001. N<strong>on</strong>local transplantati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> in the subshrub Lotus scoparius (Fabaceae). American Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Botany<br />

88:258-269.<br />

Price, M.V. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> N.M. Waser. 1979. Pollen dispersal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> optimal outcrossing in Delphinimum<br />

nels<strong>on</strong>ii. Nature 277:294-297.<br />

Quilichini, A., M. Debussche, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> J.D. Thomps<strong>on</strong>. 2001. Evidence for local <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> inthe Mediterranean isl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> endemic, Anchusa crispa Viv. (Boraginaceae).<br />

Heredity 87:190-197.<br />

Richards, C.M. 2000. Inbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> genetic rescue in a plant metapopulati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

The American Naturalist 155:383-394.<br />

Rossiter, S.J., G. J<strong>on</strong>es, R.D. Ransome, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> E.M. Barratt. 2001. Out-breeding increases<br />

survival in wild greater horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum). Proceedings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the Royal Society <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> Biological Society 22:1055-1061.<br />

Sheridan, P.M. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> D.N. Karowe. 2000. Inbreeding, <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> heterosis in the yellow<br />

pitcher plant, Sarracenia flava (Sarraceniaceae), in Virginia. American Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Botany 87:1628-1633.<br />

Waser, N.M. 1993. Populati<strong>on</strong> structure, optimal <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> assortative mating in<br />

angiosperms. Pages173-199 in N.W. Thornhill, ed., The Natural History <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Inbreeding<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Outbreeding: Theoretical <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Empirical Perspectives. University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Chicago Press,<br />

Chicago.<br />

Waser, N.M. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> M. Price. 1989. Optimal outcrossing in Ipomopsis aggregata: seed set <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fspring fitness. Evoluti<strong>on</strong> 43:1097-1109.<br />

——. 1991. Outcrossing distance <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Delphinium nels<strong>on</strong>ii: pollen loads, pollen tubes,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> seed set. Ecology 72:171-179.——. 1994. Crossing distance <str<strong>on</strong>g>effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Delphinium<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

18

nels<strong>on</strong>ii: <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>inbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> depressi<strong>on</strong> in progeny fitness. Evoluti<strong>on</strong><br />

48:842-852.<br />

Waser, N.M., M. Price, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> R.G. Shaw. 2000. Outbreeding depressi<strong>on</strong> varies am<strong>on</strong>g cohorts<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ipomopsis aggregata planted in nature. Evoluti<strong>on</strong> 54:485-491.<br />

Wentworth, J.B. 1998. Castilleja levisecta, a threatened South Puget Sound prairie species.<br />

Pages 101-104 in P. Dunn <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> K. Ewing (eds.), Ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the South<br />

Puget Sound Prairie L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape. The Nature C<strong>on</strong>servancy, Seattle, Washingt<strong>on</strong>.<br />

U.S. Fish <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Service. 2000. Recovery plan for the <strong>golden</strong> <strong>paintbrush</strong> (Castilleja<br />

levisecta). U.S. Fish <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Service, Portl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Oreg<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Inbreeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>outbreeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Castilleja levisecta, 2003<br />

19