Booklet

Booklet

Booklet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

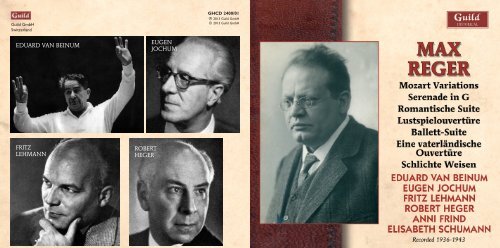

Guild GmbH<br />

Switzerland<br />

GHCD 2400/01<br />

2013 Guild GmbH<br />

© 2013 Guild GmbH<br />

EDUARD VAN BEINUM<br />

EUGEN<br />

JOCHUM<br />

FRITZ<br />

LEHMANN<br />

ROBERT<br />

HEGER

CD1<br />

MAX REGER (1873-1916)<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

Eine Lustspielouvertüre, Op.120 7:08<br />

Staatskapelle Berlin, FRITZ LEHMANN, 10 May 1941 – Odeon O-9121<br />

Serenade in G, Op.95<br />

I. Allegro molto 12:59<br />

II. Vivace a Burlesca 3:34<br />

III. Andante semplice 10:24<br />

IV. Allegro con spirito 13:24<br />

Berliner Philharmoniker, EUGEN JOCHUM, 8 July 1943 – Urania URLP 7052<br />

Eine Ballett-Suite, Op.130<br />

I. Entrée. Tempo di marcia 2:56<br />

II. Colombine. Adagietto 3:52<br />

III. Harlequin. Vivace 2:07<br />

IV. Pierrot et Pierrette. Larghetto 3:20<br />

V. Valse d amour. Sostenuto 2:54<br />

VI. Finale. Presto 2:24<br />

Concertgebouw Orkest Amsterdam, EDUARD van BEINUM,<br />

17–21 May 1943 – Polydor 68227–229, 2355–2360 GE 5<br />

Waldeinsamkeit, Op.76 Nr.3 1:57<br />

Des Kindes Gebet, Op.76 Nr.22 2:29<br />

ANNI FRIND, Orchestra, Bruno Seidler-Winkler<br />

11 March 1936 – Electrola E. G. 3643, 0RA 1124–1125<br />

Mariä Wiegenlied, Op.76 Nr.52 2:06<br />

Zum Schlafen, Op.76 Nr.59 2:07<br />

ELISABETH SCHUMANN, Orchestra<br />

22 and 2 November 1937 – Electrola D.A. 1619; OEA 5900–5901<br />

A GUILD HISTORICAL RELEASE<br />

• Master source: The collection of Jürgen Schaarwächter, Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe<br />

• Remastering: Peter Reynolds<br />

• Final master preparation: Reynolds Mastering, Colchester, England<br />

• Photos of Max Reger by L. O. Weber (Meiningen, 1915) courtesy of Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe<br />

• Design: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford<br />

• Art direction: Guild GmbH<br />

• Executive co-ordination: Guild GmbH<br />

• We would like to express our gratitude to the assistance of Professor Dr. Jan Derom (Belgium),<br />

Rob Kruijt, Koog aan de Zaan (Netherlands), Gert Schäfer (Schlangenbad), Professor Dr. Klaus<br />

Schöler (Kreuztal) and Jörg Wyrschowy, Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, Frankfurt/Main.<br />

The second Eichendorff poem was translated by John Bernhoff around 1900.<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

Guild GmbH, Moskau 314b, 8262 Ramsen, Switzerland<br />

Tel: +41 (0) 52 742 85 00 Fax: +41 (0) 52 742 85 09 (Head Office)<br />

Guild GmbH, PO Box 5092, Colchester, Essex CO1 1FN, Great Britain<br />

e-mail: info@guildmusic.com World WideWeb-Site: http://www.guildmusic.com<br />

WARNING: Copyright subsists in all recordings under this label. Any unauthorised broadcasting, public<br />

performance, copying or re-recording thereof in any manner whatsoever will constitute an infringement of such<br />

copyright. In the United Kingdom licences for the use of recordings for public performance may be obtained from<br />

Phonographic Performances Ltd., 1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9EE.

ALSO AVAILABLE ON GUILD<br />

CD2<br />

GHCD 2371<br />

GHCD 2372<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

Eine romantische Suite, Op.125<br />

I. Notturno 9:57<br />

II. Scherzo 7:25<br />

III. Finale 10:45<br />

Groot Symfonieorkest van Zender Brussel, FRITZ LEHMANN<br />

7–15 April 1942 – Odeon O-9136–39<br />

Variationen und Fuge über ein Thema von Mozart, Op.132<br />

Thema. Andante grazioso 2:37<br />

Variation 1. L’istesso tempo 2:27<br />

Variation 2. Poco agitato 2:12<br />

Variation 3. Con moto 1:33<br />

Variation 4. Vivace 0:40<br />

Variation 5. Quasi presto 1:28<br />

Variation 6. Sostenuto (quasi adagietto) 2:14<br />

Variation 7. Andante grazioso 2:48<br />

Variation 8. Molto sostenuto 7:51<br />

Fugue. Allegretto grazioso 8:42<br />

Concertgebouw Orkest Amsterdam, EDUARD van BEINUM<br />

17–21 May 1943 – Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 68222–226, 2369–2378<br />

Eine vaterländische Ouvertüre, Op.140 14:01<br />

Städtisches Orchester Berlin, ROBERT HEGER<br />

10 November 1942 – Polydor 59194–95, gs 2013–2016 gs<br />

GHCD 2363 GMCD 7192<br />

3

The knowledge of the music of Max Reger is usually restricted to a comparatively small<br />

number of compositions, particularly for organ. Yet his orchestral output was smaller<br />

maybe in number, but not in substance. From fairly early on, Reger was interested in<br />

orchestral music, one of his first compositions as a fifteen-years old boy (soon after destroyed<br />

by the composer) being a lengthy Overture in B minor. Several early orchestral attempts have, if<br />

ever, been performed only once, e.g. an Overture in D minor (Heroide) (1889) and two first (and<br />

only) movements of Symphonies in D minor (1890 and 1902 respectively). All these projects were<br />

abandoned by the composer (the 1902 symphonic movement not even completed), and it was to<br />

take until 1904 that Reger produced his first fully valid orchestral work, which he called Sinfonietta<br />

but which is a Symphony in all but name. The controversy arising from its first performance in<br />

Munich (following the premiere performance in Essen in 1905) and insinuating that Reger wasn’t<br />

an orchestral composer of any real capability at all resulted in the composer taking up the challenge<br />

and providing an orchestral work of the utmost clarity and refinement. He called this work, hardly<br />

shorter in duration than the Sinfonietta, Serenade in G, Op. 95, and the work received its first<br />

performance on 23 October 1906 in Cologne. Eugen Jochum (1902–1987) became an important<br />

interpreter of the work, making a studio recording of it for Telefunken in Amsterdam on 21-22 June<br />

1943 (which has been re-issued on Tahra). Also two live renderings of the Serenade conducted by<br />

Jochum have survived, one, much later, also from Amsterdam (22 January 1979), the other being a<br />

concert performance on 8 July 1943 with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Reichspropagandaamt. In<br />

1941 Jochum toured the occupied countries with the Berlin Philharmonic and was, in 1944, one of<br />

the “Divinely Gifted” in a list authorized by Hitler. He used this position, at least as long as he could<br />

until the end of the 1930s, to perform music of composers otherwise banned in Germany, including<br />

Hindemith, Stravinsky, and Bartók. The 1943 Berlin Reichsrundfunk broadcast was after the war<br />

taken to the United States and released there on the Urania label.<br />

It is interesting to see which of Reger’s works were the first ones to be recorded. Figuring in<br />

central place is the orchestral music, which may be explained by the comparatively easy accessibility<br />

of some of the compositions. It took sometime before a larger selection of chamber music was<br />

recorded, due, as in fact with Reger’s organ music, to its complex texture, which would suffer from<br />

4<br />

surprising that famous singers not always chose Reger’s own orchestrations but new arrangements<br />

were made for them. Furthermore, Zum Schlafen and Waldeinsamkeit, two lieder from Reger’s<br />

famous collection of a total of sixty Schlichte Weisen, Op. 76, were not orchestrated by Reger himself.<br />

Of course, sopranos Elisabeth Schumann (1888–1952) and Anni Frind (1900–1987) were only two<br />

of several singers to record Reger lieder in the 1930s and ‘40s, but their individual voices fit most<br />

perfectly the four delightful miniatures. Schumann, who emigrated in 1937 to the United States, is<br />

of course the much better-known name as one of the best lieder singers of her time. Frind on the<br />

contrary, who retired from performing at the outbreak of the war in order to avoid collaboration<br />

with the Nazis, is nowadays almost totally forgotten, not least because of the smaller number of her<br />

recordings; still she was considered one of the most highly recorded lyric sopranos in Germany<br />

during the 1920s and ‘30s.<br />

© Jürgen Schaarwächter, 2013<br />

Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe<br />

9

Hermann Abendroth lacked the fugue – so van Beinum was the first to profit from the advanced<br />

sound recording quality being a by-product of warfare.<br />

The Reger orchestral composition that matched best the demands of the Nazi forces was a<br />

work that here receives its CD premiere – the Vaterländische Ouvertüre (Patriotic Overture),<br />

Op. 140, Reger’s last orchestral composition which had received its first performance in the same<br />

concert as the Mozart Variations, on 8 January 1915 in Wiesbaden, conducted by Reger himself.<br />

An occasional work by nature, it is pure Reger by matter of contrapuntal mastery and motivic<br />

development, culminating in the “contrapuntal miracle” of a combination of the German National<br />

Anthem, the chorale Nun danket alle Gott, and the patriotic songs Die Wacht am Rhein and Ich hab<br />

mich ergeben, and so musically was only in part suited to Nazi purposes. It was, amongst others,<br />

performed (and recorded) by the Orchestra of the Deutschlandsender on the eve of the Second<br />

World War, the studio recording for the Deutsche Grammophon following only some three years<br />

later. This comparatively late recording date makes clear that there were in Reger’s music matters<br />

concerned that were largely diverging from the Nazis’ intentions. Yet since the Second World War<br />

the work has never been performed again in Germany, Reger’s (short-lived) “Great War” euphoria<br />

being stigmatized by the abuse of the work during dark times. The conductor of the only-ever<br />

commercial recording of the overture was Robert Heger (1886–1978), who had been an opera<br />

conductor nearly all of his life, including engagements at Strasbourg, Ulm, Vienna, Munich and the<br />

Berlin State Opera (from 1936); he concluded his career in Bavaria from 1950 as Chief Conductor<br />

at the Munich State Opera and (until 1954) President of the Conservatoire.<br />

In concert performance Reger often combined piano and chamber music with sections of piano<br />

lieder, and the same practice was regularly encountered in vocal orchestral concerts; yet Reger as<br />

a performer was deeply dissatisfied with the impression the lieder made after the performance of<br />

a symphony or a concerto, and so he began orchestrating songs by himself and by others (Brahms,<br />

Grieg, Schubert, Wolf), such arrangements reaching their peak in the Meiningen years 1914-5.<br />

Apart from some exceptions (for example Kirsten Flagstad recorded Reger’s orchestration of Grieg’s<br />

Eros, Op. 70 No. 1 for EMI) these orchestrations remained largely forgotten until well into the late<br />

1990s, when Horst Stein recorded all twelve of Reger’s own lied orchestrations. And so it is not<br />

8<br />

the possibilities of sound recordings in these times. This might also have affected Reger’s orchestral<br />

works, but from the earliest attempts of recording orchestral Reger (in Fritz Busch’s rendering of<br />

part of the Mozart Variations Op. 132, in Stuttgart in 1919, GHCD 2371) it became clear that Reger<br />

is an orchestral composer who, with sufficient rehearsal time, is very successful on record.<br />

Another important exponent of German Reger conductors of the time was, apart from Jochum<br />

and Fritz Busch, Fritz Lehmann (1904–1956). Lehmann, a prolific Bach conductor who died during<br />

a performance of the St. Matthew Passion from a heart attack, had conducted his career largely<br />

unhindered by the Nazis, from 1938 as General Music Director in Wuppertal, a post which he<br />

held until 1946. He resigned, however, in 1944 from the post as Artistic Director of the Göttingen<br />

International Händel Festival after conflict with the Nazi authorities. Like Jochum, Lehmann served<br />

Nazi purposes by conducting in the occupied countries. There, with the Brussels Radio Symphony<br />

Orchestra, he made a studio recording of Reger’s Romantische Suite, Op. 125, the composer’s most<br />

“impressionist” work written in 1912 during his position as Chief Conductor of the Meiningen<br />

Court Orchestra (a position previously held, amongst others, by Hans von Bülow, Richard Strauss<br />

and Fritz Steinbach). The composition based on three poems by Joseph von Eichendorff. Since the<br />

poems are essential to the work’s understanding, they are given here.<br />

Notturno<br />

Hörst du nicht die Quellen gehen<br />

Zwischen Stein und Blumen weit<br />

Nach den stillen Waldesseen,<br />

Wo die Marmorbilder stehen<br />

In der schönen Einsamkeit?<br />

Von den Bergen sacht hernieder,<br />

Weckend die uralten Lieder,<br />

Steigt die wunderbare Nacht,<br />

Und die Gründe glänzen wieder,<br />

Wie du’s oft im Traum gedacht ...<br />

5<br />

Notturno<br />

Don’t you hear the springs running<br />

between stone and flowers far<br />

t’ward the calm wood lakes,<br />

where the marble statues stand<br />

in fine solitude?<br />

From the mountains, gently,<br />

awakening ancient songs,<br />

wondrous night descends,<br />

and the meadows shine again,<br />

as you’d dreamt many times ...

Scherzo<br />

Bleib bei uns! wir haben den Tanzplan im Tal<br />

Bedeckt mit Mondesglanze,<br />

Johanneswürmchen erleuchten den Saal,<br />

die Heimchen spielen im Tanze.<br />

Die Freude, das schöne leichtgläubige Kind,<br />

Es wiegt sich in Abendwinden:<br />

Wo Silber auf Zweigen und Büschen rinnt,<br />

Da wirst du die schönsten finden.<br />

Finale<br />

Steig nur, Sonne,<br />

Auf die Höhn!<br />

Schauer wehn,<br />

Und die Erde bebt vor Wonne.<br />

Kühn nach oben<br />

Greift aus Nacht<br />

Waldespracht,<br />

Noch von Träumen kühl durchwoben ...<br />

Scherzo<br />

Stay with us! our playmates await but our call<br />

to join our moonlight prancing,<br />

ten thousand glowworms illumine the hall,<br />

the crickets play to our dancing.<br />

There pleasure, our princess, lies in her bower<br />

‘mid blossoms with odours teeming:<br />

the moonbeams o’er silver each op’ning flower,<br />

come, youth, where our Queen lies dreaming!<br />

Finale<br />

Rise, sun,<br />

onto the heights!<br />

Showers blow,<br />

and earth writhes blissfully.<br />

Boldly upwards<br />

spreads from night<br />

forest’s splendour,<br />

yet coolly interweaved by dreams ...<br />

One year previously, Lehmann had conducted a Berlin studio recording of Reger’s Eine<br />

Lustspielouvertüre, Op. 120 of 1911, a Comedy Overture which has never attained the popularity<br />

of the sister-work composed by Ferruccio Busoni some years previously. The reason is simple –<br />

the contrapuntal textures provided by Reger were quite a different matter for the performers who<br />

simply required more rehearsal time – in the past as in the present day, a serious drawback to a<br />

work’s popularity. Which does not mean that the composition isn’t a most spirited work of art,<br />

taking up the best qualities of the Hiller Variations, Op. 100 and foreshadowing the Ballet Suite.<br />

The Ballet Suite, Op. 130 was another product from Reger’s Meiningen years, written one year<br />

after the Romantic Suite. In it, Reger enforced his increasingly concept of critical “condensation”<br />

(a technique already found in earlier substantial compositions such as the Sinfonietta or the Violin<br />

Concerto, Op. 101), deleting one movement altogether after it had already been engraved. In the<br />

Ballet Suite, Reger relates to the figures of the commedia dell’arte, a feature that just went back<br />

into fashion during the days of composition. The deleted movement was devoted to one more of<br />

the commedia dell’arte characters, Pantalon, Harlequin’s opponent in the love matters concerning<br />

Colombine, Pierrot and Pierrette being another love-couple of the commedia dell’arte. With Valse<br />

d’amour Reger wrote a comparatively popular piece which was for some time regularly performed<br />

in the light music sector and which Reger also arranged for piano solo (as early as 1914 there were<br />

already arrangements of this movement for small and salon orchestra, and a version for violin and<br />

piano was published in 1933). The first complete studio recording of the work was made in occupied<br />

Amsterdam by the Concertgebouw Orkest, conducted by Eduard van Beinum, the orchestra’s<br />

co-principal conductor alongside Willem Mengelberg. Van Beinum’s way with the orchestra<br />

was altogether different from Mengelberg’s, who was an absolute autocrat, while van Beinum<br />

understood his musicians as partners rather than subordinates. Furthermore, van Beinum detested<br />

the Nazis and kept himself as aloof as he could; that he at the same time was an ardent performer<br />

of Reger (who had once had a strong controversy with Mengelberg on the first performance of the<br />

Concert im alten Styl op. 123) and made two studio recordings of his orchestral music, is caused by<br />

the fact that the compositions of Reger, who died in 1916, were attempted to be misused by the Nazi<br />

forces but at the same time had a complexity and a wealth of modern compositional techniques that<br />

simply would not do for the intended purposes.<br />

The other van Beinum Reger recording for Deutsche Grammophon was the Mozart Variations,<br />

Op. 132, Reger’s most popular work, which had already received its first complete recording in<br />

1937 by Karl Böhm (with the Dresden Staatskapelle); another recording made in 1942 in Paris by<br />

6 7