Didactics of mathematics: more than mathematics and school! - CIMM

Didactics of mathematics: more than mathematics and school! - CIMM

Didactics of mathematics: more than mathematics and school! - CIMM

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ZDM Mathematics Education (2007) 39:165–171<br />

DOI 10.1007/s11858-006-0016-x<br />

ORIGINAL ARTICLE<br />

<strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>: <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>school</strong>!<br />

Rudolf Straesser<br />

Accepted: 22 December 2006 / Published online: 10 February 2007<br />

Ó FIZ Karlsruhe 2007<br />

Abstract In the discipline didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>,<br />

the didactical triangle <strong>of</strong> subject–teacher–learner is<br />

sometimes too narrowly interpreted by shortening the<br />

human side <strong>of</strong> didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> ( fi teacher–<br />

learner) to teaching <strong>and</strong> learning in institutionalised<br />

settings, especially <strong>school</strong>s. In his working group <strong>of</strong> the<br />

‘‘Institute for <strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mathematics’’ (IDM) at Bielefeld<br />

University, Hans-Georg Steiner inserted good<br />

reasons <strong>and</strong> strong motivations to analyse technical <strong>and</strong><br />

vocational <strong>mathematics</strong> education as well as the vocational<br />

<strong>and</strong> everyday use <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>. In doing so, he<br />

helped developing research on teaching, learning <strong>and</strong><br />

use <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> outside <strong>school</strong>s. The text gives a<br />

short description <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> in technical <strong>and</strong><br />

vocational education <strong>and</strong> identifies major issues <strong>and</strong><br />

problems in this field <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> education: realistic<br />

modelling, situated <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> the hiding <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> in black boxes as opposed to a utilitarian<br />

reduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> for the workplace. This implies<br />

widening the horizon <strong>of</strong> <strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mathematic,<br />

opening a perspective on the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’<br />

much appreciated by Hans-Georg Steiner.<br />

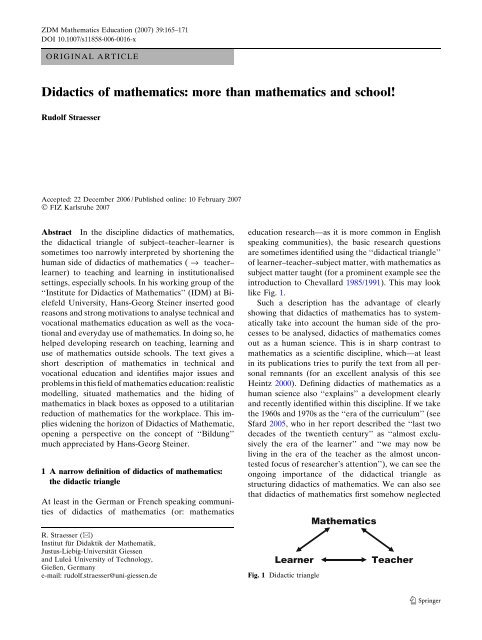

1 A narrow definition <strong>of</strong> didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>:<br />

the didactic triangle<br />

At least in the German or French speaking communities<br />

<strong>of</strong> didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> (or: <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

education research—as it is <strong>more</strong> common in English<br />

speaking communities), the basic research questions<br />

are sometimes identified using the ‘‘didactical triangle’’<br />

<strong>of</strong> learner–teacher–subject matter, with <strong>mathematics</strong> as<br />

subject matter taught (for a prominent example see the<br />

introduction to Chevallard 1985/1991). This may look<br />

like Fig. 1.<br />

Such a description has the advantage <strong>of</strong> clearly<br />

showing that didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> has to systematically<br />

take into account the human side <strong>of</strong> the processes<br />

to be analysed, didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> comes<br />

out as a human science. This is in sharp contrast to<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> as a scientific discipline, which—at least<br />

in its publications tries to purify the text from all personal<br />

remnants (for an excellent analysis <strong>of</strong> this see<br />

Heintz 2000). Defining didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as a<br />

human science also ‘‘explains’’ a development clearly<br />

<strong>and</strong> recently identified within this discipline. If we take<br />

the 1960s <strong>and</strong> 1970s as the ‘‘era <strong>of</strong> the curriculum’’ (see<br />

Sfard 2005, who in her report described the ‘‘last two<br />

decades <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century’’ as ‘‘almost exclusively<br />

the era <strong>of</strong> the learner’’ <strong>and</strong> ‘‘we may now be<br />

living in the era <strong>of</strong> the teacher as the almost uncontested<br />

focus <strong>of</strong> researcher’s attention’’), we can see the<br />

ongoing importance <strong>of</strong> the didactical triangle as<br />

structuring didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>. We can also see<br />

that didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> first somehow neglected<br />

R. Straesser (&)<br />

Institut für Didaktik der Mathematik,<br />

Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen<br />

<strong>and</strong> Luleå University <strong>of</strong> Technology,<br />

Gießen, Germany<br />

e-mail: rudolf.straesser@uni-giessen.de<br />

Fig. 1 Didactic triangle<br />

123

166 R. Straesser<br />

the human parts <strong>of</strong> its discipline by concentrating on<br />

the subject matter side via the focus on the curriculum.<br />

The focus on subject matter, the focus on <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

had different faces in different countries. In France for<br />

instance, the IREM movement clearly defined itself as<br />

coming from an epistemological fundament. Some<br />

French colleagues even suggested to define the<br />

fundamental ‘‘Didactique des Mathématiques’’ as<br />

‘‘experimental epistemology’’ (according to Brousseau<br />

(1986, p. 103): ‘‘épistémologie expérimentale’’). For<br />

Germany, we can exemplify the focus on subject matter<br />

with the then widely accepted definition ‘‘didactics<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> is the scientific development <strong>of</strong> courses<br />

to be effectively used to learn in the area <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>.<br />

It is also made up <strong>of</strong> the practical teaching <strong>of</strong><br />

such courses <strong>and</strong> their empirical evaluation. This includes<br />

reflections on the aims <strong>and</strong> subject matter<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> such courses’’ (‘‘Didaktik der Mathematik<br />

ist die Wissenschaft von der Entwicklung praktikabler<br />

Kurse für das Lernen im Bereich Mathematik sowie<br />

der praktischen Durchführung und empirischen<br />

Überprüfung der Kurse einschliesslich der Überlegungen<br />

zur Zielsetzung der Kurse und der St<strong>of</strong>fauswahl’’,<br />

see Griesel (1971, p. 296), nearly identical in<br />

Griesel (1974); a <strong>more</strong> recent, internationally read text<br />

is Wittmann (1992, English version 1995). In the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> the 1970s, Hans-Georg Steiner also took<br />

didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as fundamentally defined by<br />

the knowledge to be taught, by <strong>mathematics</strong>—as can<br />

be seen from his publication on ‘‘Bildung’’ (see Steiner<br />

1972). He described didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as<br />

‘‘thinking through <strong>mathematics</strong> under the perspective<br />

<strong>of</strong> the elementary <strong>and</strong> the motivation for the learner’’<br />

(loc. cit., free translation from p. 326; ‘‘Das Durchdenken<br />

des Gebäudes der Mathematik unter dem<br />

Gesichtspunkt des Elementaren und im Hinblick auf<br />

die Motivation des Lernenden gibt dieser Wissenschaft<br />

ein lebensnahes Fundament ...’’). Until around the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 1970s, the so-called St<strong>of</strong>fdidaktik was the predominant<br />

approach to didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> in<br />

Germany, sometimes even reducing didactics <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> to a mere ‘‘elementarisation’’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

for the purpose <strong>of</strong> its teaching.<br />

At the end <strong>of</strong> the 1970s, Steiner had a broader definition<br />

<strong>of</strong> didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>. He stated that the<br />

constraints <strong>and</strong> factors, which determine the classroom<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> its changeability, belong to didactics<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>. This includes the complex processes <strong>of</strong><br />

social interaction related to the teaching <strong>and</strong> learning <strong>of</strong><br />

content matter <strong>and</strong> ways <strong>of</strong> behaviour (free translation<br />

by RS <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Mathematikdidaktik wird dabei in einem<br />

erweiterten Sinne verst<strong>and</strong>en -als vorwiegend materialorientierte<br />

Entwicklungsarbeit, Einfügung RS, wonach<br />

sowohl die den mathematischen Unterricht und<br />

seine Veränderbarkeit bestimmenden Bedingungen<br />

und Faktoren als auch die komplexen sozialen Interaktionsprozesse<br />

im Unterricht in ihrem Zusammenhang<br />

mit der Vermittlung und dem Erwerb von Inhalten und<br />

Verhaltensweisen wesentliche Best<strong>and</strong>teile bzw. Dimensionen<br />

der Untersuchungsgegenstände sind’’; see<br />

Steiner 1978, p. XL). Obviously, <strong>and</strong> probably in relation<br />

with the creation <strong>of</strong> the national research institute<br />

for didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> (Institut für Didaktik der<br />

Mathematik—IDM) in Bielefeld, Steiner looked further<br />

<strong>than</strong> the curriculum <strong>and</strong> course developers abundant<br />

at that time—at least in Germany. Nevertheless,<br />

this perspective was still concentrating on the process <strong>of</strong><br />

teaching <strong>and</strong> learning in <strong>school</strong>s, institutions to <strong>of</strong>fer (an<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong>) <strong>mathematics</strong> to everybody.<br />

2 An opening: <strong>mathematics</strong> in technical<br />

<strong>and</strong> vocational education<br />

About 10 years later <strong>and</strong> in France, we find a slightly<br />

broader definition: didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> (is) the<br />

science <strong>of</strong> the specific conditions <strong>of</strong> the diffusion <strong>of</strong><br />

mathematical knowledge useful for the functioning <strong>of</strong><br />

the human institutions (‘‘La didactique des mathématiques<br />

se place ... dans le cadre des sciences cognitives<br />

comme la science des conditions spécifiques de la diffusion<br />

des connaissances mathématiques utiles au<br />

fonctionnement des institutions humaines’’, see<br />

Brousseau 1994, p. 52). Here, didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

has left the narrow area <strong>of</strong> <strong>school</strong>s <strong>and</strong> looks into the<br />

diffusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> in society at large.<br />

Even if nearly invisible in his list <strong>of</strong> publications,<br />

Steiner too had crossed this borderline <strong>of</strong> <strong>school</strong>s in his<br />

activities: Because <strong>of</strong> his interest in the pedagogical<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’ (see the text entitled ‘‘Mathematik<br />

und Bildung’’; Steiner 1972) <strong>and</strong> an ongoing<br />

German debate on a reform <strong>of</strong> upper secondary<br />

teaching in general, Steiner had taken the job <strong>of</strong> a<br />

scientific counsellor <strong>of</strong> a major German reform project—the<br />

‘‘Kollegstufe’’ piloted by Herwig Blankertz.<br />

Kollegstufe aimed at <strong>of</strong>fering upper secondary education<br />

for virtually everybody in need <strong>of</strong> this—from the<br />

future unskilled worker to the young adult planning an<br />

academic career. This reform project especially fitted<br />

with the intentions <strong>of</strong> the Bielefeld institute IDM <strong>and</strong><br />

Hans-Georg Steiner, because Blankertz wanted to<br />

build his project on the joint efforts <strong>of</strong> the different<br />

subject matter didactics (‘‘Fachdidaktiken’’) available<br />

at that time. Steiner integrated a <strong>mathematics</strong> teacher<br />

from the ‘‘Kollegstufe’’-project in his working group<br />

in Bielefeld after having made upper secondary<br />

123

<strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>: <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>school</strong>! 167<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> teaching <strong>and</strong> learning the field <strong>of</strong> research<br />

<strong>of</strong> his working group in the mid 1970s. With a first<br />

academic training as a <strong>mathematics</strong> teacher for Gymnasium,<br />

Steiner at that time broadened his interests to<br />

all types <strong>of</strong> education <strong>and</strong> training at the upper secondary<br />

level. As a consequence <strong>and</strong> in the German<br />

organisation <strong>of</strong> the educational system, this implied<br />

that <strong>mathematics</strong> also in technical <strong>and</strong> vocational<br />

education had to be studied in his working group. In<br />

addition to this <strong>and</strong> with the apprenticeship system as a<br />

major part <strong>of</strong> technical <strong>and</strong> vocational education <strong>and</strong><br />

training, the German upper secondary educational<br />

system <strong>of</strong>fered an opportunity not to study only classroom<br />

environments, but also look into <strong>mathematics</strong> in<br />

commercial <strong>and</strong> industrial settings.<br />

2.1 Vocational <strong>mathematics</strong>: a description<br />

Contrary to the practice <strong>of</strong> defining <strong>mathematics</strong> education<br />

at upper secondary by <strong>mathematics</strong> to prepare<br />

for university studies, looking into <strong>mathematics</strong> in<br />

technical <strong>and</strong> vocational education implies a different<br />

approach. The book edited by Bessot <strong>and</strong> Ridgeway<br />

(2000) gives an excellent overview <strong>of</strong> research into this<br />

field, showing that—apart from university bound<br />

young adults—one has to also care for the vast<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> adolescents who <strong>more</strong> or less directly go<br />

into the labour market <strong>and</strong> everyday life. In most,<br />

especially industrialised countries, some sort <strong>of</strong> mathematical<br />

knowledge is part <strong>of</strong> the vocational training—if<br />

there is an institutionalised training for<br />

vocations at all.<br />

Once upon a time, UNESCO described this training<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or education as ‘‘the educational process ...<br />

(which) involves, in addition to general education, the<br />

study <strong>of</strong> technologies <strong>and</strong> related sciences <strong>and</strong> the<br />

acquisition <strong>of</strong> practical skills <strong>and</strong> knowledge relating<br />

occupations in various sectors <strong>of</strong> economic <strong>and</strong> social<br />

life’’ (UNESCO 1978, p. 17). Even if it is methodologically<br />

rather difficult to describe the mathematical<br />

needs <strong>of</strong> the workplace, the common core <strong>of</strong> this part<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> was <strong>of</strong>ten described as ‘‘basic arithmetic,<br />

percentages <strong>and</strong> proportion, ... for some vocations,<br />

these techniques already seem to be all the<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong>’ topics needed’’ (cf. Straesser <strong>and</strong><br />

Zevenbergen 1996, p. 653). Apart from this, it seems to<br />

be very difficult to discern the ‘real’ pr<strong>of</strong>essional use <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong>. Straesser <strong>and</strong> Zevenbergen (loc. cit.) cite<br />

from the 1985-Cockcr<strong>of</strong>t-report: ‘‘It is therefore not<br />

possible to produce definitive lists <strong>of</strong> the mathematical<br />

topics <strong>of</strong> which a knowledge will be needed in order to<br />

carry out jobs with a particular title’’. Additional<br />

algebraic techniques seem to be in use in technical <strong>and</strong><br />

economical vocations, Geometry use seems to be restricted<br />

to the technical <strong>and</strong> building sector (loc. cit.).<br />

Little is known about the <strong>mathematics</strong> ‘‘needed’’ for<br />

the upper part <strong>of</strong> the qualification spectrum, even if<br />

‘‘<strong>mathematics</strong> as a service subject’’ is part <strong>of</strong> a lot <strong>of</strong><br />

academic training for future engineers <strong>and</strong> management<br />

personnel (see the pertinent ICMI-study no. 3 on<br />

this issue with Howson et al. 1988 as its proceedings).<br />

If one looks into the list <strong>of</strong> publications <strong>of</strong> Hans-<br />

Georg Steiner, studies into this broader field <strong>of</strong> upper<br />

secondary (<strong>mathematics</strong>) education are nearly invisible—with<br />

one major exception: Steiner <strong>and</strong> Straesser<br />

(1982). Here, the vast range <strong>of</strong> technical <strong>and</strong> vocational<br />

education is narrowed down to that part <strong>of</strong> the training<br />

<strong>and</strong> education <strong>of</strong> young adults who try a direct entry to<br />

the world <strong>of</strong> work after compulsory <strong>school</strong>ing. At least<br />

in Germany, this is still <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> half <strong>of</strong> the population<br />

<strong>and</strong> has a special organization called ‘Lehrlingsausbildung’,<br />

internationally known as ‘apprenticeship’,<br />

i.e. joint efforts <strong>of</strong> vocational colleges <strong>and</strong> companies<br />

to train a skilled workforce. From this short description,<br />

a major tension may already be obvious: How to<br />

cope with the specific, but ‘‘needs’’ <strong>of</strong> a whole variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> different vocations from hairdressing to the building<br />

sector <strong>and</strong> business administration or electrical <strong>and</strong><br />

even computer based information technology? What<br />

about the mathematical ‘‘needs’’ <strong>of</strong> this diverse occupational<br />

fields <strong>and</strong> (in Germany: <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> 400)<br />

vocations? What has didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> to <strong>of</strong>fer<br />

to this training/education linking classrooms <strong>of</strong> vocational<br />

colleges to workplaces in the different occupational<br />

fields?<br />

2.2 Realistic modelling<br />

Looking into vocational <strong>mathematics</strong>—in the narrow<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> a direct move or preparation for workplaces—<strong>of</strong>fers<br />

a chance, which <strong>mathematics</strong> in compulsory<br />

<strong>school</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten do not have: with the workplace <strong>and</strong><br />

vocation to be trained for clearly identified, there is an<br />

obvious field <strong>of</strong> application for <strong>mathematics</strong> in this<br />

type <strong>of</strong> training/education. To put it in a different<br />

wording: vocational <strong>mathematics</strong> in principle immediately<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers a field outside <strong>mathematics</strong>, to which<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> can be applied, it does not have to look in<br />

the vague ‘‘rest <strong>of</strong> the world’’ <strong>of</strong>ten mentioned when<br />

applications <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> are discussed. If the<br />

vocational field ‘‘asks’’ for <strong>mathematics</strong> to be used<br />

(<strong>and</strong> this is not always obvious, see the next subsection),<br />

the vocational field <strong>of</strong>fers a vast array <strong>of</strong> applications<br />

for <strong>mathematics</strong>.<br />

If we take the example <strong>of</strong> technical vocations related<br />

to metalwork, Schilling (1984, p. 116; in a text for a<br />

123

168 R. Straesser<br />

developmental project piloted by Steiner <strong>and</strong> Straesser)<br />

stressed the importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> for this<br />

vocational area, but also pointed to the fact that<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> is used as a ‘strategic’ tool to model the<br />

workplace situation, to fulfil the quantification needs <strong>of</strong><br />

the vocational situation in order to have easy predictions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the application <strong>of</strong> machines <strong>and</strong> procedures.<br />

Mathematics is not needed as such, it <strong>of</strong>fers a (very<br />

versatile) tool to model the workplace situation. Consequently,<br />

the vocational theory is not interested in a<br />

deep underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> mathematical concepts or procedures,<br />

but in an effective <strong>and</strong> fast prediction <strong>of</strong> the<br />

vocational situation (loc. cit., p. 118).<br />

A comparable description can be found for the<br />

workplaces related to (traditional, not computer related)<br />

electricity: Rauner (1984, p. 151) denies <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

an independent role in the training <strong>of</strong> future<br />

qualified worker in electricity surroundings, but mentions<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as a help to underst<strong>and</strong><br />

vocational situations—with trigonometric functions as<br />

the prototypic example helping to underst<strong>and</strong> alternating<br />

current. He even goes as far as saying that<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing electro technical devices is simply<br />

impossible without <strong>mathematics</strong>—but wants these<br />

mathematical models preferably presented in diagrams<br />

<strong>and</strong> graphs, not in numbers or equations (loc. cit., p.<br />

152f; for examples see the end <strong>of</strong> his paper).<br />

2.3 The utilitarian reduction<br />

Looking into <strong>mathematics</strong> in vocational training <strong>and</strong><br />

education is one efficient way to walk out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

classroom to study <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> its use out <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>school</strong>. This nevertheless implies a temptation, which<br />

Hans-Georg Steiner always resisted, but should nevertheless<br />

be mentioned: Studying workplace use <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten tends to reduce the purpose <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> to its importance for aims outside <strong>mathematics</strong>.<br />

Falling into this trap implies the idea, that<br />

teaching <strong>and</strong> learning <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> is (mainly, if not<br />

only) done for utilitarian reasons, for the sake <strong>of</strong> the<br />

role <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>’ in its applications. From the<br />

description <strong>of</strong> the developmental project mentioned<br />

above, one can see that Steiner (<strong>and</strong> his team) did not<br />

reduce vocational training to utilitarian purposes.<br />

Apart from three other problems <strong>of</strong> teaching <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

in this type <strong>of</strong> vocational training, the project<br />

wanted to take into account the tension between<br />

vocational <strong>and</strong> general education (in German: ‘‘beruflicher<br />

und allgemeiner Bildung’’, see Steiner <strong>and</strong><br />

Straesser 1982, p.16).<br />

The modelling approach <strong>of</strong> Sect. 2.2, especially the<br />

comments from the metalwork <strong>and</strong> electricity area,<br />

already show that a simplistic utilitarian approach to<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> is inappropriate for vocational training—last<br />

not least because the sheer practice <strong>of</strong> the<br />

workplace is not interested in the workers underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

the processes <strong>of</strong> production <strong>and</strong> distribution,<br />

but will only look into a continuous functioning <strong>of</strong><br />

machines <strong>and</strong> the labour force. Research into <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

at the workplace has shown the limitations <strong>of</strong><br />

such an approach in <strong>more</strong> detail: as long as the production/distribution<br />

process goes uninterrupted by<br />

unexpected events, goes without (unforeseen) problems,<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing the process (maybe with the help<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>) is not necessary, sometimes even disturbing.<br />

The worker may even override the information<br />

produced by a mathematical model.<br />

A nice confirmation <strong>of</strong> this statement from the<br />

banking sector may be the comment <strong>of</strong> a person ‘‘in<br />

charge <strong>of</strong> support <strong>and</strong> maintenance <strong>of</strong> computer<br />

equipment’’ in an investment bank (see Noss <strong>and</strong><br />

Hoyles 1996, p. 7f). He commented his evaluation <strong>of</strong> a<br />

piece <strong>of</strong> equipment by using a pre-programmed<br />

spreadsheet by ‘‘I press the button <strong>and</strong> see what it says.<br />

.... I look at the answer. If it seems to indicate what I<br />

think we should do, I use the number to justify my<br />

decision. If not, I ignore it, or put in figures which will<br />

support my hunch.’’ It its all too obvious that <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

cannot be used as an unquestioned, simple<br />

model <strong>of</strong> the vocational situation.<br />

A quote from an experienced teacher trainer in the<br />

metalworking area shows a different limitation <strong>of</strong> a too<br />

simplistic utilitarian reduction <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

in vocational situations: ‘‘Mathematics in<br />

vocational education is serving <strong>more</strong> as a background<br />

knowledge for explaining <strong>and</strong> avoiding mistakes, recognising<br />

safety risks, judicious measurement <strong>and</strong> various<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> estimation. ... Not practice at the<br />

workplace but deepening <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>essional knowledge,<br />

education to a responsible use <strong>of</strong> tools <strong>and</strong> machines<br />

<strong>and</strong> the underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong> coping with<br />

everyday mathematical problems legitimise <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

in vocational education’’ (quoted from Appelrath<br />

1985, pp. 133–139; translation R.S.). In the<br />

statement from metalwork, <strong>mathematics</strong> takes a specific<br />

role to further an underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the workplace<br />

situation. It is not directly operative in the situation on<br />

the shop floor.<br />

2.4 Black boxes<br />

As a consequence, <strong>mathematics</strong> is far from obvious in<br />

vocational situations—somehow confirming the difficulties<br />

to identify vocational <strong>mathematics</strong> already<br />

mentioned in Sect. 2.1. Difficulties to find <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

123

<strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>: <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>school</strong>! 169<br />

in the workplace seem to even grow with the increasing<br />

use <strong>of</strong> (modern) technology. Some people even speak<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ,,disappearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> from society’s<br />

perception’’ (title <strong>of</strong> Straesser 2002). The use <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> (in a simple utilitarian sense) as backbone<br />

<strong>of</strong> models <strong>of</strong> a vocational situation is <strong>of</strong>ten implemented<br />

in graphs <strong>and</strong> algorithms, maybe even machines,<br />

hides the inherent mathematical procedures<br />

<strong>and</strong> concepts from the direct perception <strong>of</strong> the user.<br />

S/he may see the situation as not containing any<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong>, because the <strong>mathematics</strong> parts is ‘‘crystallised’’<br />

in artefacts like graphs, tables or machines<br />

like automatic wages, control devices <strong>and</strong> protocols.<br />

The user might only be confronted with some pointer,<br />

which has to be kept within a given interval (in a<br />

steering/control situation) or answered by a certain<br />

activity (for instance in a buying situation with the<br />

price automatically given by a digital balance; for details<br />

<strong>of</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> weighing, see Straesser<br />

2002). The highly integrated automatic control systems<br />

<strong>of</strong> the flow <strong>of</strong> cash <strong>and</strong> goods are another illustration <strong>of</strong><br />

this tendency to hide <strong>mathematics</strong> from being noticed.<br />

The whole development can be described as the<br />

gradual, but steady introduction <strong>of</strong> ‘‘black boxes’’ into<br />

the production <strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> goods <strong>and</strong> services<br />

in a modern economy.<br />

Consequences for the teaching <strong>and</strong> learning <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> are far from obvious. In accordance with<br />

the proclaimed habit <strong>of</strong> mathematicians to always go<br />

back to the source <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>and</strong> leave no statement<br />

unproved, some educators explicitly opt for an<br />

opening <strong>of</strong> these boxes, which should go as far as<br />

possible—even avoiding the use <strong>of</strong> such algorithms <strong>and</strong><br />

automatisms as long as they have not been explained<br />

<strong>and</strong> understood (for an example see Buchberger 1989).<br />

In sharp contrast, Peschek for instance clearly stated<br />

the impossibility <strong>of</strong> such a procedure, advocating an<br />

intelligent <strong>and</strong> efficient use <strong>of</strong> black boxes (see Peschek<br />

1999, p. 270).<br />

Straesser (2002) even goes further in pointing to the<br />

fact that the role <strong>of</strong> technology in itself can be quite<br />

ambivalent. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, (modern computer)<br />

technology may be a very effective way to hide the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> from societal perception. ‘‘On the<br />

other h<strong>and</strong>, ... the same technology can be used to<br />

demystify the black boxes, to show the mathematical<br />

relations <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer an opportunity to explore the<br />

inherent, implemented relations in a way workplace<br />

reality would never allow because <strong>of</strong> the risk <strong>of</strong><br />

material, financial <strong>and</strong> time losses. The practice <strong>of</strong><br />

using sophisticated <strong>mathematics</strong> can be brought to the<br />

foreground <strong>and</strong> hence to the consciousness <strong>of</strong> the user<br />

by appropriate s<strong>of</strong>tware <strong>and</strong> vocational training/education.<br />

It is modern computer technology <strong>and</strong> appropriate<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware which can be successfully used to really<br />

explore <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the underlying ... <strong>mathematics</strong>’’<br />

(Straesser 2002, p. 130).<br />

2.5 Situated <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

What was reported about <strong>mathematics</strong> at the workplace<br />

<strong>and</strong> vocational training/education related to this<br />

all starts from a common, normally not contested<br />

assumption: <strong>mathematics</strong> is a special type <strong>of</strong> knowledge<br />

with a specific structure, special ways <strong>of</strong> proving<br />

<strong>and</strong> a clear borderline to separate <strong>mathematics</strong> from<br />

the ‘rest <strong>of</strong> the world’ (as Pollak described it at ICME<br />

3, see Pollak 1979). A modelling approach to applications<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as well as the idea <strong>of</strong> black boxes<br />

hiding <strong>mathematics</strong> heavily rely on this separation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> from the rest <strong>of</strong> the world.<br />

Workplace <strong>mathematics</strong> somehow questions this<br />

idea—last not least because the difficulties <strong>of</strong> identifying<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> used in the workplace. Inspired by<br />

research into the use <strong>of</strong> mathematical ideas in workplace<br />

situations like banking, nursing, piloting an airplane<br />

<strong>and</strong> engineering, Hoyles <strong>and</strong> Noss (2004)<br />

detailed the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘situated abstractions’ in<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> they had already brought forward earlier.<br />

• ‘‘mathematical meanings that emerge through webbing<br />

with tools that ‘embed’ <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

• in use or communication display ‘correct’ mathematical<br />

invariants<br />

• are expressed with the language <strong>of</strong> the tools <strong>and</strong><br />

community<br />

• are abstracted within, not away from (the workplace,<br />

insert RS) community’’.<br />

It is obvious that these situated abstractions related<br />

to <strong>mathematics</strong> are no longer part <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> or<br />

‘the rest <strong>of</strong> the world’ alone, but are a new type <strong>of</strong><br />

knowledge bridging the divide between <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> the rest <strong>of</strong> the world.<br />

To make this idea functional for teaching <strong>and</strong><br />

learning, Hoyles added the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘techno-mathematical<br />

literacies’ (see Hoyles <strong>and</strong> Noss 2004). Even if<br />

these concepts are developed from research into<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> in the workplace, these concepts can<br />

obviously be used in a <strong>more</strong> general sense, in the<br />

general scientific debate about teaching <strong>and</strong> learning<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong>—not isolating workplace <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

from the vast majority <strong>of</strong> a didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

research community not necessarily interested in<br />

workplace <strong>mathematics</strong>.<br />

123

170 R. Straesser<br />

3 Utilitarian <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’<br />

In Sect. 2, the consequences <strong>of</strong> looking into vocational<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> education <strong>and</strong> some results <strong>of</strong> research<br />

into this type <strong>of</strong> teaching <strong>and</strong> learning <strong>and</strong> on research<br />

into <strong>mathematics</strong> at the workplace have been described.<br />

One could see how this field <strong>of</strong> research throws<br />

a new light onto the human struggle with <strong>mathematics</strong>,<br />

how this breaking out <strong>of</strong> the narrow confines <strong>of</strong> the<br />

institution classroom/<strong>school</strong> can add to didactics <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mathematics</strong>. Looking into <strong>mathematics</strong> in the workplace<br />

<strong>and</strong> in vocational education obviously has<br />

something to <strong>of</strong>fer to didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> as a<br />

scientific discipline. One could also see that current<br />

research in this field is still mainly concerned with the<br />

subject matter <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> its role in the workplace<br />

<strong>and</strong> vocational education. The role <strong>and</strong> problems<br />

<strong>of</strong> the human learner are still somehow neglected in<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> in vocational education.<br />

The typical German concept <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’ may be<br />

an appropriate way to overcome this limitation. Even if<br />

the German word cannot be easily translated into<br />

English without loosing its distinct meaning, it may be<br />

a way to conceptually bridge the divide between the<br />

subject matter (to be) taught <strong>and</strong> the human being<br />

struggling with this subject matter. Steiner simply cited<br />

the well-known formula defining ‘‘Bildung’’ as what is<br />

left when everything that has been learned is forgotten<br />

(‘‘Wenn Bildung ... das ist, was übrig bleibt, wenn man<br />

vergessen hat, was man gelernt hat’’; Steiner 1972, p.<br />

334f). The afore-mentioned German educationalist<br />

Herwig Blankertz especially looked into Bildung from<br />

the perspective <strong>of</strong> vocational education (see Blankertz<br />

1969). In this paper, it is simply impossible to present<br />

the long-st<strong>and</strong>ing debate on ‘‘Bildung’’ <strong>and</strong> its implications<br />

for <strong>mathematics</strong> education in general. But it<br />

was the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’, which made Steiner<br />

aware <strong>of</strong> the fundamental role <strong>of</strong> the learner (see the<br />

citation in Sect. 1) <strong>and</strong> opened the way to his activities<br />

in vocational education, implying that Steiner inserted<br />

the question <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’ into the vocational project<br />

he took part in. Mathematics education in <strong>and</strong> for the<br />

workplace can pr<strong>of</strong>it from taking into account the human<br />

side <strong>of</strong> the teaching/learning process—possibly<br />

with the help <strong>of</strong> the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘‘Bildung’’.<br />

There is also a lesson to be learnt for general<br />

<strong>mathematics</strong> education. Some ten years later in the<br />

1980s, the human part <strong>of</strong> didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> is so<br />

evident, that Steiner makes ‘‘Bildung’’ a point <strong>of</strong> defence<br />

<strong>of</strong> the reform <strong>of</strong> the upper secondary <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

education bound for academic studies (the<br />

‘‘neugestaltete gymnasiale Oberstufe’’). According to<br />

Steiner, the pre-defined curriculum for everybody<br />

(with academic aspirations) should be substituted by an<br />

individually defined ‘‘diet’’ <strong>of</strong> learning objects <strong>and</strong><br />

experiences in order to have an adequate upper secondary<br />

education including <strong>mathematics</strong> (‘‘... die Beratungen<br />

und ... Betreuungen der Schüler ... unter dem<br />

Aspekt der Wahl eines individuellen Bildungsganges<br />

und damit unter bestimmte mit dem Bildungsgang<br />

verbundene Kompetenzentwicklungen zu stellen’’, see<br />

Steiner 1984, p. 21—explicitly referring to Blankertz<br />

<strong>and</strong> his reform work). Here again—<strong>and</strong> for general<br />

education, ‘‘Bildung’’ is the keyword to fight a utilitarian<br />

reduction <strong>of</strong> teaching <strong>and</strong> learning <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

in favour <strong>of</strong> a <strong>mathematics</strong> created for the individual<br />

learner.<br />

References<br />

Appelrath, K.-H. (1985). Zur Verwendung von Mathematik und<br />

zur Situation des Fachrechnens im Berufsfeld Metalltechnik<br />

(dargestellt an zwei Unterrichtsbeispielen). In P. Bardy, W.<br />

Blum, & H. G. Braun (Eds.), Mathematik in der Berufsschule<br />

- Analysen und Vorschläge zum Fachrechenunterricht.<br />

(pp. 127–139). Essen: Girardet.<br />

Bessot, A., & Ridgway, J. (2000). Education for <strong>mathematics</strong> in<br />

the workplace (Vol. 24). Dordrecht: Kluwer.<br />

Blankertz, H. (1969). Bildung im Zeitalter der grossen Industrie.<br />

Pädagogik, Schule und Berufsbildung im 19. Jahrhundert.<br />

Berlin: Hermann Schroedel.<br />

Blum, W., & Straesser, R. (1992). Mathematikunterricht in<br />

beruflichen Schulen zwischen Berufskunde und Allgemeinbildung.<br />

Zentralblatt für Didaktik der Mathematik 24(7),<br />

242–247.<br />

Brousseau, G. (1986). Forschungstendenzen der Mathematikdidaktik<br />

in Frankreich. Journal für Mathematikdidaktik 7(2/3),<br />

95–120.<br />

Brousseau, G. (1994). Perspectives pour la didactique des<br />

mathématiques. In M. Artigue (Eds.), Vingt Ans de Didactique<br />

des Mathématiques en France - Hommage à Guy<br />

Brousseau et Gerard Vergnaud (pp. 51–66). Grenoble: La<br />

Pensée Sauvage.<br />

Buchberger, B. (1989). Should students learn integration rules?<br />

(RISC-Linz-Series No. 89-07.0). Linz: RISC.<br />

Chevallard, Y. (1985/1991). La transposition didactique. Grenoble:<br />

Pensées sauvages.<br />

Griesel, H. (1971). Die Neue Mathematik für Lehrer und<br />

Studenten - B<strong>and</strong> 1: Mengen, Zahlen, Relationen, Topologie<br />

(Vol. 1). Hannover: Schroedel.<br />

Griesel, H. (1974). Überlegungen zur Didaktik der Mathematik<br />

als Wissenschaft. Zentralblatt für Didaktik der Mathematik<br />

6(3), 115–119.<br />

Heintz, B. (2000). Die Innenwelt der Mathematik. Zur Kultur<br />

und Praxis einer beweisenden Disziplin. Heidelberg: Springer.<br />

Howson, A. G., Kahane, J. P., Lauginie, P. & Turckheim, E.<br />

(Eds.). (1988). Mathematics as a service subject. Cambridge:<br />

Cambridge University Press (additional selected papers<br />

published by Springer (1988): Clements, R. B., Lauginie, P.<br />

& Turckheim, E. (Eds.) as CISM Courses <strong>and</strong> Lectures No.<br />

305).<br />

Hoyles, C. & Noss, R. (2004). Abstraction in workplace expertise.<br />

Copenhagen: ICME 10 conference website (paper from<br />

TSG 7 at www.ICME10.dk).<br />

123

<strong>Didactics</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>: <strong>more</strong> <strong>than</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>school</strong>! 171<br />

Noss, R., & Hoyles, C. (1996). The visibility <strong>of</strong> meanings:<br />

modelling the <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>of</strong> banking. International Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Computers for Mathematical Learning 1(1), 3–31.<br />

Peschek, W. (1999). Mathematische Bildung meint auch Verzicht<br />

auf Wissen. In G. Kadunz, G. Ossimitz, W. Peschek, E.<br />

Schneider, &B. Winkelmann (Eds.), Mathematische Bildung<br />

und neue Technologien (pp. 263–270). Stuttgart: Teubner.<br />

Pollak, H. O. (1979). The interaction between <strong>mathematics</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

other <strong>school</strong> subjects. In I. C. o. M. I. (ICMI) (Ed.), New<br />

trends in <strong>mathematics</strong> teaching (Vol. 4, pp. 232–248). Paris:<br />

United Nations Educational, Scientific <strong>and</strong> Cultural Organisation<br />

(UNESCO).<br />

Rauner, F. (1984). Die Lehre von der Elektrotechnik in der<br />

Berufsschule. In R. Straesser (Ed.), Bausteine zu einer<br />

Didaktik des mathematischen Unterrichts an Berufsschulen<br />

(Vol. 34, pp. 129–160). Bielefeld: Institut für Didaktik der<br />

Mathematik (IDM).<br />

Schilling, E.-G. (1984). Didaktischer Bezugsrahmen für die<br />

Beurteilung von Funktion und Rolle der Mathematik im<br />

Unterricht der Berufsschule (Berufsfeld Metalltechnik). In<br />

R. Straesser (Ed.), Bausteine zu einer Didaktik des mathematischen<br />

Unterrichts an Berufsschulen (Vol. 34, pp. 97–<br />

128). Bielefeld: Institut für Didaktik der Mathematik<br />

(IDM).<br />

Sfard, A. (2005). What could be <strong>more</strong> practical <strong>than</strong> a good<br />

research? On mutual relations between research <strong>and</strong><br />

practice <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> eduaction (Survey Team 1 Report<br />

on Relations between research <strong>and</strong> Practice <strong>of</strong> Mathematics<br />

Education). Educational Studies in Mathematics 58, 393–413.<br />

Steiner, H.-G. (1972). Mathematik und Bildung. In H. Meschkowski<br />

(Ed.), Grundlagen der modernen Mathematik (pp.<br />

310–340). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.<br />

Steiner, H.-G. (1978). Didaktik der Mathematik – Einleitung. In<br />

H.-G. Steiner (Ed.), Didaktik der Mathematik (Vol.<br />

CCCLXI, pp. IX–XLVIII). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche<br />

Buchgesellschaft.<br />

Steiner, H.-G. (1984). Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Bildung.<br />

Kritisch-konstruktive Fragen und Bemerkungen zum<br />

Aufruf einiger Fachverbände. In M. Reiss & H.-G. Steiner<br />

(Eds.), Mathematikkenntnisse – Leistungsmessung – Studierfähigkeit<br />

(Vol. 9, pp. 5–59). Köln: Aulis Verlag Deubner.<br />

Steiner, H.-G., & Straesser, R. (1982). Mathematik in der<br />

Berufsschule – gegenwärtiger St<strong>and</strong>, Entwicklungstendenzen,<br />

drängende Probleme. In R. Straesser (Ed.), Mathematik<br />

in der Berufsschule (Vol. 28, pp. 9–51). Bielefeld: Institut für<br />

Didaktik der Mathematik (IDM).<br />

Straesser, R. (2002). On the disappearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong> from<br />

society’s perception. In H.-G. Weig<strong>and</strong> (Eds.), Developments<br />

in <strong>mathematics</strong> education in German-speaking countries.<br />

selected papers from the annual conference on<br />

didactics <strong>of</strong> <strong>mathematics</strong>, Bern, 1999 (pp. 124–133). Hildesheim:<br />

Franzbecker.<br />

Straesser, R., & Zevenbergen, R. (1996). Further <strong>mathematics</strong><br />

mducation. In A. Bishop (Eds.), International H<strong>and</strong>book on<br />

Mathematics Education (Vol. 1, pp. 647–674). Dordrecht:<br />

Kluwer.<br />

UNESCO. (1978). Terminology <strong>of</strong> technical <strong>and</strong> vocational<br />

education – Terminologie de l’enseignement technique et<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionnel. Paris: UNESCO.<br />

Wittmann, E. C. (1992). Mathematikdidaktik als ‘‘design science’’.<br />

Journal für Mathematikdidaktik, 13(1), 55–70. English<br />

version (1995): Mathematics Education as a ‘‘Design<br />

Science’’. Educational Studies in Mathematics (29), 355–374.<br />

123