The Archi - November 2011 - Alpha Rho Chi

The Archi - November 2011 - Alpha Rho Chi

The Archi - November 2011 - Alpha Rho Chi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

12<br />

Preserving<br />

America’s Best Idea<br />

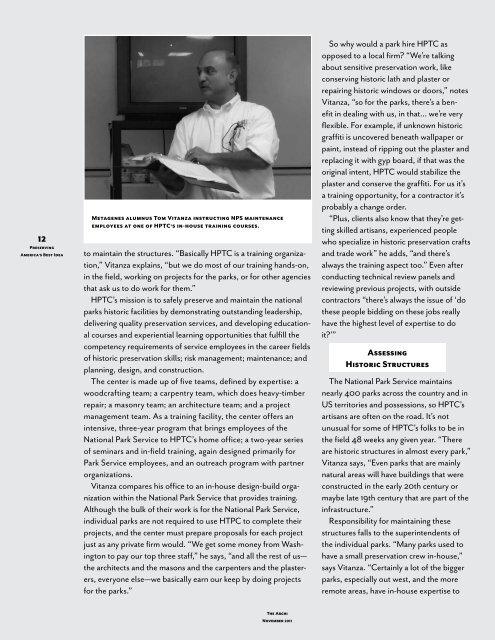

Metagenes alumnus Tom Vitanza instructing NPS maintenance<br />

employees at one of HPTC’s in-house training courses.<br />

to maintain the structures. “Basically HPTC is a training organization,”<br />

Vitanza explains, “but we do most of our training hands-on,<br />

in the field, working on projects for the parks, or for other agencies<br />

that ask us to do work for them.”<br />

HPTC’s mission is to safely preserve and maintain the national<br />

parks historic facilities by demonstrating outstanding leadership,<br />

delivering quality preservation services, and developing educational<br />

courses and experiential learning opportunities that fulfill the<br />

competency requirements of service employees in the career fields<br />

of historic preservation skills; risk management; maintenance; and<br />

planning, design, and construction.<br />

<strong>The</strong> center is made up of five teams, defined by expertise: a<br />

woodcrafting team; a carpentry team, which does heavy-timber<br />

repair; a masonry team; an architecture team; and a project<br />

management team. As a training facility, the center offers an<br />

intensive, three-year program that brings employees of the<br />

National Park Service to HPTC’s home office; a two-year series<br />

of seminars and in-field training, again designed primarily for<br />

Park Service employees, and an outreach program with partner<br />

organizations.<br />

Vitanza compares his office to an in-house design-build organization<br />

within the National Park Service that provides training.<br />

Although the bulk of their work is for the National Park Service,<br />

individual parks are not required to use HTPC to complete their<br />

projects, and the center must prepare proposals for each project<br />

just as any private firm would. “We get some money from Washington<br />

to pay our top three staff,” he says, “and all the rest of us—<br />

the architects and the masons and the carpenters and the plasterers,<br />

everyone else—we basically earn our keep by doing projects<br />

for the parks.”<br />

So why would a park hire HPTC as<br />

opposed to a local firm? “We’re talking<br />

about sensitive preservation work, like<br />

conserving historic lath and plaster or<br />

repairing historic windows or doors,” notes<br />

Vitanza, “so for the parks, there’s a benefit<br />

in dealing with us, in that… we’re very<br />

flexible. For example, if unknown historic<br />

graffiti is uncovered beneath wallpaper or<br />

paint, instead of ripping out the plaster and<br />

replacing it with gyp board, if that was the<br />

original intent, HPTC would stabilize the<br />

plaster and conserve the graffiti. For us it’s<br />

a training opportunity, for a contractor it’s<br />

probably a change order.<br />

“Plus, clients also know that they’re getting<br />

skilled artisans, experienced people<br />

who specialize in historic preservation crafts<br />

and trade work” he adds, “and there’s<br />

always the training aspect too.” Even after<br />

conducting technical review panels and<br />

reviewing previous projects, with outside<br />

contractors “there’s always the issue of ‘do<br />

these people bidding on these jobs really<br />

have the highest level of expertise to do<br />

it?’”<br />

Assessing<br />

Historic Structures<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Park Service maintains<br />

nearly 400 parks across the country and in<br />

US territories and possessions, so HPTC’s<br />

artisans are often on the road. It’s not<br />

unusual for some of HPTC’s folks to be in<br />

the field 48 weeks any given year. “<strong>The</strong>re<br />

are historic structures in almost every park,”<br />

Vitanza says, “Even parks that are mainly<br />

natural areas will have buildings that were<br />

constructed in the early 20th century or<br />

maybe late 19th century that are part of the<br />

infrastructure.”<br />

Responsibility for maintaining these<br />

structures falls to the superintendents of<br />

the individual parks. “Many parks used to<br />

have a small preservation crew in-house,”<br />

says Vitanza. “Certainly a lot of the bigger<br />

parks, especially out west, and the more<br />

remote areas, have in-house expertise to<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Archi</strong><br />

<strong>November</strong> <strong>2011</strong>