Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem • Mini-course • 11–12 January ...

Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem • Mini-course • 11–12 January ...

Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem • Mini-course • 11–12 January ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

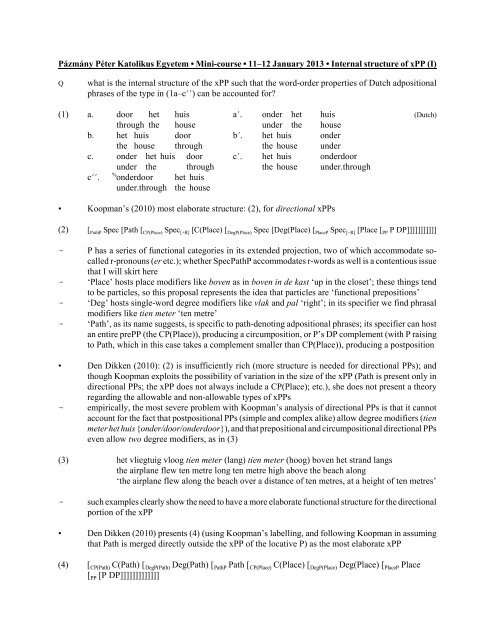

<strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> <strong>•</strong> <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> <strong>•</strong> <strong>11–12</strong> <strong>January</strong> 2013 <strong>•</strong> Internal structure of xPP (I)<br />

Q<br />

what is the internal structure of the xPP such that the word-order properties of Dutch adpositional<br />

phrases of the type in (1a–c) can be accounted for?<br />

(1) a. door het huis a. onder het huis (Dutch)<br />

through the house under the house<br />

b. het huis door b. het huis onder<br />

the house through the house under<br />

c. onder het huis door c. het huis onderdoor<br />

under the through the house under.through<br />

c.<br />

%<br />

onderdoor het huis<br />

under.through the house<br />

<strong>•</strong> Koopman’s (2010) most elaborate structure: (2), for directional xPPs<br />

(2) [ PathP Spec [Path [ CP(Place) Spec [+R] [C(Place) [ DegP(Place) Spec [Deg(Place) [ PlaceP Spec [+R] [Place [ PP P DP]]]]]]]]]]]<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

P has a series of functional categories in its extended projection, two of which accommodate socalled<br />

r-pronouns (er etc.); whether SpecPathP accommodates r-words as well is a contentious issue<br />

that I will skirt here<br />

‘Place’ hosts place modifiers like boven as in boven in de kast ‘up in the closet’; these things tend<br />

to be particles, so this proposal represents the idea that particles are ‘functional prepositions’<br />

‘Deg’ hosts single-word degree modifiers like vlak and pal ‘right’; in its specifier we find phrasal<br />

modifiers like tien meter ‘ten metre’<br />

‘Path’, as its name suggests, is specific to path-denoting adpositional phrases; its specifier can host<br />

an entire prePP (the CP(Place)), producing a circumposition, or P’s DP complement (with P raising<br />

to Path, which in this case takes a complement smaller than CP(Place)), producing a postposition<br />

<strong>•</strong> Den Dikken (2010): (2) is insufficiently rich (more structure is needed for directional PPs); and<br />

though Koopman exploits the possibility of variation in the size of the xPP (Path is present only in<br />

directional PPs; the xPP does not always include a CP(Place); etc.), she does not present a theory<br />

regarding the allowable and non-allowable types of xPPs<br />

empirically, the most severe problem with Koopman’s analysis of directional PPs is that it cannot<br />

account for the fact that postpositional PPs (simple and complex alike) allow degree modifiers (tien<br />

meter het huis {onder/door/onderdoor}), and that prepositional and circumpositional directional PPs<br />

even allow two degree modifiers, as in (3)<br />

(3) het vliegtuig vloog tien meter (lang) tien meter (hoog) boven het strand langs<br />

the airplane flew ten metre long ten metre high above the beach along<br />

‘the airplane flew along the beach over a distance of ten metres, at a height of ten metres’<br />

<br />

such examples clearly show the need to have a more elaborate functional structure for the directional<br />

portion of the xPP<br />

<strong>•</strong> Den Dikken (2010) presents (4) (using Koopman’s labelling, and following Koopman in assuming<br />

that Path is merged directly outside the xPP of the locative P) as the most elaborate xPP<br />

(4) [ CP(Path) C(Path) [ DegP(Path) Deg(Path) [ PathP Path [ CP(Place) C(Place) [ DegP(Place) Deg(Place) [ PlaceP Place<br />

[ [P DP]]]]]]]]]]]]]<br />

PP

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

2<br />

<br />

but he rejects (4) immediately: ‘We have now posited two full-blown functional sequences leading<br />

up to CP, one for Place and one for Path, in the extended projection of just a single lexical head: P.<br />

This is not right. The structure in [(4)] is ill formed: no single lexical head supports two extended<br />

projections that are simultaneously present. This entails that, in order to accommodate the full array<br />

of modification and r-word placement possibilities of directional PPs, the path domain must be an<br />

extended projection of a lexical P head in its own right. In other words, [(4)] should be revised as<br />

in [(5)], with a lexical PP in between Path and CP(Place), and with the projections outside PP Dir<br />

serving as members of the extended projection of P , the directional counterpart to P .’<br />

Dir<br />

Loc<br />

(5) [ CP(Path) C(Path) [ DegP(Path) Deg(Path) [ PathP Path [ PP P Dir [ CP(Place) C(Place) [ DegP(Place) Deg(Place)<br />

[ Place [ P DP]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]<br />

PlaceP PP Loc<br />

<strong>•</strong> Den Dikken (2010) goes on to demonstrate that, though (5) can be employed in full, many directional<br />

xPPs are structurally less elaborate than (5)<br />

he seeks to provide a principled account for the restrictions on the variation in the size of the locative<br />

and directional structural layers of the xPP<br />

he does so by relabelling some of the functional projections in the Koopman-style xPP on the basis<br />

of cross-categorial parallels with the extended projections of verbs and nouns<br />

‘Place’ and ‘Path’ are aspectual functional categories, corresponding to event aspect in the verbal<br />

domain (and number in the nominal domain) — the difference between locative and directional Ps<br />

is likened to the distinction between stative and dynamic Vs<br />

‘Deg(Place)’ and ‘Deg(Path)’ are likened to T and Dem, all brought together under the umbrella of<br />

‘deixis’ — temporal deixis (‘present’ vs ‘past’ vs ‘future’); demonstrative deixis (‘this’ vs ‘that’ vs<br />

‘yon’); spatial deixis (‘here/at the speaker’ vs ‘there/not at the speaker’ vs ‘yonder/far from the<br />

speaker’; ‘towards the speaker’ vs ‘away from the speaker’)<br />

(6) a. [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ V ...]]]]<br />

b. [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ N ...]]]]<br />

c. [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P ...]]]]<br />

CP<br />

[FORCE]<br />

DxP<br />

[TENSE]<br />

AspP<br />

[EVENT]<br />

VP<br />

CP<br />

[DEF]<br />

DxP<br />

[PERSON]<br />

AspP<br />

[NUM]<br />

NP<br />

CP<br />

[SPACE]<br />

DxP<br />

[SPACE]<br />

AspP<br />

[SPACE]<br />

PP<br />

<strong>•</strong> V can take a variety of xVP complements, but one logically possible complementation pattern is<br />

unattested: there is, apparently, a local dependency relationship between Asp and Dx, so (7b) fails<br />

(7) a. V [ VP V ...]<br />

b. *V [ AspP Asp<br />

[EVENT]<br />

[ VP V ...]]<br />

c. V [ DxP Dx<br />

[TENSE]<br />

[ AspP Asp<br />

[EVENT]<br />

[ VP V ...]]]<br />

d. V [ C [ Dx<br />

[TENSE]<br />

[ Asp<br />

[EVENT]<br />

[ V ...]]]]<br />

CP DxP AspP VP<br />

<br />

assuming that this restriction carries over to spatial aspect as well, and that no special restrictions<br />

hold on xPP beyond this general one on the licensing of aspect, we expect that P Dir should be able<br />

to take three possible xPP complements<br />

(8) a. P Dir [ PP P Loc DP]<br />

b. *P Dir [ AspP Asp<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ PP P Loc DP]]<br />

c.<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[PLACE]<br />

P Dir [ DxP Dx [ AspP Asp [ PP P Loc DP]]]<br />

d. P [<br />

[PLACE]<br />

C [<br />

[PLACE]<br />

Dx [<br />

[PLACE]<br />

Asp [ P DP]]]]<br />

Dir CP DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

P Dir can, in turn, have a variety of extended projections; only some of these can be V-complements

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

3<br />

(9) a. V [ PP P Dir ...]<br />

b. *V [ AspP Asp<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ PP P Dir ...]]]]<br />

c. *V [ DxP Dx<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ AspP Asp<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ PP P Dir ...]]]]<br />

d. V [ C<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ Dx<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ Asp<br />

[PATH]<br />

[ P ...]]]]<br />

CP DxP AspP PP Dir<br />

(9b) is ungrammatical because Asp is locally dependent on Dx, throughout (cf. *(7b) and *(8b))<br />

(9c) is ungrammatical because Dx<br />

[PATH]<br />

cannot be anaphorically bound by Dx<br />

[TENSE]; whenever a Dx<br />

head is not the immediate complement of C, it must be anaphorically bound by a higher Dx head (cf.<br />

Guéron & Hoekstra’s 1993 ‘T-chain’), but such binding succeeds only if binder and bindee are of<br />

the same type (i.e., both temporal, or both numeral, or both spatial)<br />

<strong>•</strong> non-directional xPPs serving as V-complements are apparently never smaller than CP<br />

[PLACE]<br />

— there<br />

is no postpositional order in non-directional xPPs; extraction from non-directional xPPs succeeds<br />

only in the case of r-pronouns; there is no P-incorporation with non-directional xPPs<br />

[NB: we can relate these properties of non-directional xPPs to the single hypothesis that non-directional<br />

xPPs serving as V-complements are always as large as CP , but why this is ostensibly the<br />

[PLACE]<br />

case is itself not clear at all; perhaps particularly intriguing is the fact that (9a.i), below, is a grammatical<br />

structure, so P Loc can incorporate into P Dir and, subsequently, into the V cluster, but it cannot<br />

incorporate into the V cluster directly, without the mediation of P Dir]<br />

for non-directional xPPs, therefore, we only have (9e)<br />

(9) e. V [ CP C<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ DxP Dx<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ AspP Asp<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ PP P Loc DP]]]]<br />

<strong>•</strong> combining (8) and (9), we obtain (9) as the maximal space of variation in xPPs serving as verbal<br />

complements<br />

(9a.ii) is ungrammatical for the same reason (9c) is: Dx<br />

[PLACE]<br />

does not have a local C licenser, and<br />

[TENSE]<br />

cannot be anaphorically bound by the Dx of the matrix clause<br />

[PLACE]<br />

(9a.iii) is subject to speaker variation: only for those speakers who allow a locative CP in the<br />

complement of a directional verb is this structure grammatical<br />

(NB: since P Dir in the a–structures does not have an extended projection of its own, it must be<br />

incorporated into V for its licensing; P–incorporation leads to the ‘government transparency’ effect<br />

of turning the complement of the incorporated head into a derived complement of the incorporator)<br />

(9) a.i V [ P [ P DP]]<br />

a.ii *V [ P [ Dx [ Asp [ P DP]]]]<br />

%<br />

a.iii V [ P [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P DP]]]]]<br />

b. *V [ Asp [ P ...]]]]<br />

c. *V [ Dx [ Asp [ P ...]]]]<br />

d.i V [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P [ P DP]]]]]]<br />

d.ii V [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P [ Dx [ Asp [ P DP]]]]]]]<br />

d.iii V [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P [ C [ Dx [ Asp [ P<br />

DP]]]]]]]]<br />

e. V [ C<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ Dx<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ Asp<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[ P DP]]]]<br />

PP Dir PP Loc<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[PLACE]<br />

PP Dir DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

[PLACE] [PLACE] [PLACE]<br />

PP Dir CP DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

[PATH]<br />

AspP PP Dir<br />

[PATH]<br />

[PATH]<br />

DxP AspP PP Dir<br />

[PATH] [PATH] [PATH]<br />

CP DxP AspP PP Dir PP Loc<br />

[PATH] [PATH] [PATH] [PLACE] [PLACE]<br />

CP DxP AspP PP Dir DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

[PATH] [PATH] [PATH] [PLACE] [PLACE] [PLACE]<br />

CP DxP AspP PP Dir CP DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

CP DxP AspP PP Loc<br />

<br />

in total, there are four directional xPPs that can grammatically serve as verbal complements for all<br />

speakers of — (9a.i) and all versions of (9d); in addition, some speakers allow (9a.iii), which<br />

correlates three properties that distinguish these speakers’ varieties from others’ (such as mine):

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

4<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

the (in)ability of prePPs to occur in the complement of directional manner-of-motion verbs<br />

(op de heuvel wandelen ‘on the hill walk’ — grammatical on a locative reading for all<br />

speakers; ambiguous between a locative and a directional reading only for some speakers)<br />

the (in)ability of the postP portion of a circumPP to be incorporated into the verbal cluster<br />

%<br />

(dat het water onder het huis is < door>gelopen ‘that the water under the house<br />

is run)<br />

the (in)ability of the prePP portion of a circumPP to be extracted with stranding of the postP<br />

%<br />

portion ( onder welk huis is het water door gelopen? ‘under which house is the water<br />

through run’)<br />

<strong>•</strong> I will not go through the nitty gritty of the Dutch xPP data in any (further) detail here (referring you<br />

to Koopman’s and Den Dikken’s papers for extensive exemplification and discussion)<br />

I only draw attention to a major problem with Den Dikken’s analysis of circumPPs, based on (9d.iii)<br />

the claim is that circumPP order results from raising CP<br />

[PLACE]<br />

in (9d.iii), which is prepositional, to<br />

SpecCP<br />

[PATH], yielding the ‘P Loc DP P Dir’ order that characterises circumPPs<br />

the problem is that, as (3) shows, in circumPPs are simultaneously modified by both a path modifier<br />

and a place modifier, the two modifiers are adjacent, with the former preceding the latter — (3),<br />

which is the expected word order on Den Dikken’s (2010) analysis of circumPPs, is ungrammatical<br />

[PLACE]<br />

[PATH]<br />

it seems that the landing-site of leftward movement of CP must be lower than SpecCP<br />

(3) *het vliegtuig vloog [ CP(Path) [ CP(Place) tien meter (hoog) boven het strand] [tien meter (lang) langs]]<br />

the airplane flew ten metre high above the beach ten metre long along<br />

Q where is the external argument of a predicative xPP base-generated?<br />

a question not addressed by either Koopman (2010) or Den Dikken (2010)<br />

<strong>•</strong> the subject of a predicative xPP surfaces, of <strong>course</strong>, outside the entire xPP<br />

but as is well known, the surface position of a subject is not necessarily its base position: subjects<br />

have a tendency to raise<br />

Q-float is generally a good diagnostic for the position(s) harbouring an empty category linked to the<br />

subject — specifically, a trace; as Baltin notes, PRO behaves differently from raising<br />

(10) a. the children seemed all to have left<br />

b. *the children promised Mary all to leave<br />

c. *all to leave would be difficult for them<br />

<strong>•</strong> a floating Q associated with the subject of the xPP is possible inside an xPP<br />

(11) (wat de tafel betreft), [er allemaal boven op] liggen de boeken<br />

what the table concerns there all up on lie the books<br />

‘as for the table, the books are all lying up on top of it’<br />

(12) (wat de verdediging betreft), met [de spitsen [er allebei hooguit een halve meter achter]]<br />

what the defence concerns with the forwards there both at.most a half metre behind<br />

ziet de scheidsrechter nooit of het buitenspel is<br />

sees the referee never whether it off.side is<br />

‘as for the defence, with the forwards both at most half a metre behind it, the referee will<br />

never be able to see whether they’re off-side or not’

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

5<br />

<br />

<br />

the topicalisation and with-absolute constructions are ideal testing grounds because they guarantee<br />

that er, the r-pronoun, is still within the maximal xPP: in these examples, er cannot have scrambled<br />

(for obvious reasons in the case of (11); and for the with-absolute in Dutch the ungrammaticality of<br />

placement of er to the immediate right of met ‘with’ (*met er de spitsen...) indicates that scrambling<br />

is also impossible there)<br />

note that topicalisation of a predicate along with a FQ belonging to its subject is grammatical only<br />

if the subject has raised up, not if the subject of the topicalised predicate is a PRO controlled by the<br />

matrix subject (in line with Baltin’s findings)<br />

(13) a. [allebei doodziek] zijn we van de verkiezingscampagne<br />

both dead.sick are we of the election.campaign<br />

b. *[allebei naakt] stonden ze voor het raam<br />

both naked stood they in.front.of the window<br />

c. *[allebei koud] at hij de kroketten<br />

both cold ate he the croquettes<br />

<br />

<br />

Q<br />

so in (11) we must be dealing with a trace of the subject, de boeken ‘the books’, somewhere inside<br />

the fronted constituent headed by op ‘on’<br />

similarly, in (12), there must be a trace of de spitsen ‘the forwards’ somewhere inside the xPP of<br />

achter ‘behind’<br />

where is this trace?<br />

<strong>•</strong> an investigation of the xVP is helpful for comparison<br />

in (6a), I presented a reasonably detailed picture of the xVP<br />

[FORCE] [TENSE] [EVENT]<br />

(6a) [ CP C [ DxP Dx [ AspP Asp [ VP V...]]]]<br />

<br />

<br />

but (6a) conspicuously does not include the v that Chomsky (1995:Chapter 4) holds responsible for<br />

introducing the external argument of the VP predicate — the RELATOR of the predicate and its subject,<br />

in the terminology of Den Dikken (2006)<br />

there is reason to believe that this RELATOR is introduced outside the projection of Asp — one interesting<br />

argument to this effect comes from (14): (14a), with a delimited/bounded event, is an idiom<br />

and provides a different è-role to the subject than does (14b), with a non-idiomatic unbounded event<br />

(14) a. he kicked the bucket in an hour idiom only (‘he died in an hour’)<br />

b. he kicked the bucket for an hour literal only (‘his foot hit the bucket for an hour’)<br />

<br />

so I situate RP (= Chomsky’s vP; but I will use category-neutral terminology here to facilitate crosscategorial<br />

comparison) between Dx and Asp<br />

(15) [ CP C<br />

[FORCE]<br />

[ DxP Dx<br />

[TENSE]<br />

[ RP SUBJECT [RELATOR [ AspP Asp<br />

[EVENT]<br />

[ VP V...]]]]]]<br />

<strong>•</strong> transposing this to the xPP leads to the hypothesis that the subject of a predicative xPP originates<br />

within CP, once again between Dx and Asp, as in (16)<br />

[SPACE] [SPACE] [SPACE]<br />

(16) [ CP C [ DxP Dx [ RP SUBJECT [RELATOR [ AspP Asp [ PP P...]]]]]]

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

6<br />

<br />

the fact that a FQ can occur between the r-word er and boven ‘up’ (which Koopman treats as a spellout<br />

of her Place, my Asp ), as in (11), is now immediately accounted<br />

[ SPACE]<br />

for<br />

(17) [ CP er [C[SPACE] [ DxP Dx<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ RP allemaal t SU [RELATOR [ AspP Asp<br />

[SPACE]<br />

=boven [ PP op ...]]]]]]]<br />

<br />

to account for (12), we may either part ways with Koopman and treat phrasal een halve meter ‘half<br />

a metre’ as an adjunct to AspP (which would be more in line with the standard treatment of ‘time<br />

frame adverbials’ like for/in x amount of time in the literature) or assume that it is adjoined to DxP<br />

below the ‘structural subject position’ within xPP, SpecDxP, and that allebei is stranded in DxP<br />

(18) a. [ CP er [C[SPACE] [ DxP Dx<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ RP allebei t SU [RELATOR [ AspP .5m [ AspP Asp<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ PP achter ...]]]]]]]]<br />

b. [ CP er [C[SPACE] [ DxP allebei t SU [ DxP .5m [ DxP Dx<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ RP t SU [RELATOR [ AspP Asp<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ PP achter<br />

...]]]]]]]]<br />

<br />

there is empirical reason to believe that (18b) is not right: if een halve meter ‘half a metre’ could be<br />

adjoined as high as DxP, one would expect allebei to freely be able to surface to its right; but as a<br />

matter of fact, allebei can occur in this position only on a marked focus reading, with emphasis on<br />

allebei [the ‘#’ diacritic is meant to bring this out: (19b) is bad in a neutral context, but grammatical<br />

in a special pragmatic context in which focus on the FQ is felicitous]<br />

(19) a. met [de spitsen [er allebei hooguit een halve meter achter]]<br />

with the forwards there both at.most a half metre behind<br />

b.<br />

#<br />

met [de spitsen [er hooguit een halve meter allebei achter]]<br />

<br />

exactly the same effect is found in the clause, with bare-nominal time-frame adverbials like een<br />

halve minuut ‘half a minute’<br />

(20) a. ze stonden allebei een halve minuut stil<br />

they stood both a half minute still<br />

‘they both stood still for half a minute’<br />

b.<br />

#<br />

ze stonden een halve minuut allebei stil<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

this strongly enhances the parallel between spatial modifiers like een halve meter ‘half a metre’ and<br />

temporal-aspectual time-frame modifiers like een halve minuut ‘half a minute’<br />

I conclude that it is AspP, not DxP, that phrasal modifiers like een halve meter ‘half a metre’ are<br />

attached to — in parallel with time frame adverbials<br />

this now fully divorces DxP from the role that it has in Koopman’s proposal (recall that Koopman<br />

labels it ‘DegP’ and uses it specifically to host modifiers like vlak ‘right’ and tien meter ‘ten metre’)<br />

— the relabelling of DegP as DxP already loosens the link between this projection and modifiers<br />

(see Den Dikken 2010:103); the conclusion, based on the Q-float data, that even phrasal modifiers<br />

like een halve meter ‘half a metre’ are not attached to DxP/DegP, weakens that link even further<br />

<strong>•</strong> the hypothesis that the RELATOR linking the predicate to its subject is projected outside AspP is<br />

empirically supported by the fact that FQs cannot show up to the right of things like pal ‘right’ and<br />

boven ‘up’<br />

[NB: Koopman has different positions for boven (Place=Asp) and pal (Deg=Dx); with degree modifiers<br />

shifted down to AspP, this positional difference is either lost or (preferably) recast in such a<br />

way that boven appears in the complement of Asp, as a particle (cf. aux verb) between Asp and PP]

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

7<br />

(21) a. [er allemaal pal boven op] liggen de boeken [cf. (11)]<br />

there all right up on lie the books<br />

b. *[er pal allemaal boven op] liggen de boeken<br />

c. *[er pal boven allemaal op] liggen de boeken<br />

(22) *[ CP C<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ DxP Dx<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ RP SUBJECT [RELATOR [ AspP Asp<br />

[SPACE]<br />

[ PP allemaal [P...]]]]]]]<br />

<br />

Q<br />

(22) is ungrammatical because, in general, a FQ must not be c-commanded by the trace of the noun<br />

phrase that it is associated with<br />

why is (23b) ungrammatical, in stark contrast to (23a)? — put differently, why can the subject of the<br />

xPP not surface in its base-generation site in these with-absolute constructions?<br />

(23) a. met [de spitsen er allebei een halve meter achter]<br />

with the forwards there both a half metre behind<br />

b. *met [er de spitsen allebei een halve meter achter]<br />

<br />

the obvious problem with (23b) is that de spitsen, which is supposed to check Case with met, is prevented<br />

from doing so by the intervening er — more technically, with er in SpecCP , there is a<br />

[SPACE]<br />

phase boundary between met and de spitsen in (23b), which causes the derivation to crash<br />

Q where, then, is de spitsen in (23a), and how does it manage to get there?<br />

the answer to the first question must be ‘outside the CP<br />

[SPACE]<br />

of achter altogether’<br />

the answer to the second question must be ‘via raising’ — after all, de spitsen cannot receive a è-role<br />

outside CP<br />

[SPACE]<br />

(met ‘with’ in absolutive constructions is not a è-role assigner)<br />

since the xPP of achter is as large as a full CP, and since de spitsen ‘the forwards’ must have<br />

originated inside this CP and have raised out of it, the conclusion emerges that ‘NP-raising’ can traverse<br />

CP boundaries; exactly how this is possible is a topic for research<br />

[NB: in the literature on raising, grammatical cases of ‘superraising’ and ‘hyperraising’ have been<br />

documented for diverse languages; I have always taken these to be instances of (covert) ‘copy raising’<br />

instead (cf. he seems like he’s enjoying himself), which arguably does not involve trans-CP<br />

movement; possibly, this is what we are dealing with in (23a) as well]<br />

<strong>•</strong> back to (3), repeated below: a directional circumPP featuring two space-frame modifiers<br />

Q where can FQs show up in this string?<br />

to test this, we need an example in which the subject is plural, as in (24); the topicalisation cases in<br />

(25a–c) provide the experimental stimuli<br />

(24) de vliegtuigen vlogen tien meter (lang) tien meter (hoog) boven het strand langs<br />

the airplanes flew ten metre long ten metre high above the beach along<br />

‘the airplanes flew along the beach over a distance of ten metres, at a height of ten metres’<br />

(25) a. [er allebei tien meter lang tien meter hoog boven langs] vlogen de vliegtuigen<br />

there both ten metre long ten metre high above along flew the airplanes<br />

b.<br />

?[er tien meter lang allebei tien meter hoog boven langs] vlogen de vliegtuigen<br />

c.<br />

#[er tien meter lang tien meter hoog allebei boven langs] vlogen de vliegtuigen<br />

d.<br />

[er<br />

allebei tien meter lang allebei tien meter hoog boven langs] vlogen de vliegtuigen

Marcel den Dikken — <strong>Pázmány</strong> <strong>Péter</strong> <strong>Katolikus</strong> <strong>Egyetem</strong> — <strong>Mini</strong>-<strong>course</strong> 2013 — The syntax of adpositional phrases<br />

8<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

the judgements for (25a) and (25c) are clear: the former is perfect, and the latter is good only with<br />

focus on the FQ, as previously<br />

my judgement for (25b) is not perfectly crisp, but it strikes me as acceptable<br />

[(25d) sounds pretty horrid, but it is hard to say whether this is due to grammatical or extragrammatical<br />

causes (so I leave the diacritic for this sentence undecided): (25d) really is pushing the limit;<br />

it is virtually impossible to find a context that would justify the use of two FQs]<br />

this suggests that there is a subject-of-predication inside the locative portion of a complex directional<br />

PP<br />

it is the directional xPP that is predicated of de vliegtuigen; the locative portion of the directional<br />

xPP is not (directly) predicated of de vliegtuigen<br />

so we have two subjects of predication, and we also need a structural subject position inside the<br />

locative portion of the structure, in order to make it possible for the subject to raise and license a FQ<br />

(26) [ er [C [ t [Dx [ allebei t [RELATOR [ [tien meter lang [Asp [ langs<br />

[ t [C [ PRO [Dx [ allebei t [RELATOR [ [tien meter hoog [Asp [ boven<br />

[DIR] [DIR] [DIR]<br />

CP DxP SU RP SU AspP PP<br />

[LOC] [LOC] [LOC]<br />

CP er DxP RP PRO<br />

AspP PP<br />

NB<br />

though a FQ cannot be locally associated to PRO, it can of <strong>course</strong> perfectly well be associated to the<br />

trace of PRO: (10b,c) both have grammatical variants with all to the right of to<br />

<strong>•</strong> the FQ facts have thus led us to the conclusion that a complex directional circumPP such as (24) is<br />

internally a control structure — effectively just the same as what we have in, say, (27)<br />

(27) the children both tried [PRO to both be successful]<br />

<br />

this result, if it holds up to further scrutiny, solidifies the parallel between xPPs and xVPs, and justifies<br />

Den Dikken’s (2010) decision to relabel Koopman’s functional projections as AspP and DxP<br />

<strong>•</strong> at least two empirical questions remain<br />

Q1 how to deal with word orders in which the FQ appears in front of the r-pronoun, as in (28)?<br />

?<br />

(28) [allemaal er pal boven op] lagen de boeken<br />

all there right up on lie the books<br />

<br />

er could potentially be in a lower position here, in particular, SpecAspP (cf. Koopman’s SpecPlaceP)<br />

Q2 how to deal with the difference between definite er and indefinite ergens in (29)?<br />

(29) a. [er allemaal pal boven op] liggen de boeken<br />

there all right up on lie the books<br />

b. [ergens allemaal pal boven op] liggen de boeken<br />

somewhere all right up on lie the books<br />

b. [allemaal ergens pal boven op] liggen de boeken<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

while (29b) is grammatical, it forces a [+specific] reading onto indefinite ergens; for a non-specific<br />

reading, (29b) must be used<br />

this is probably merely a matter of scope (relative to the universal FQ), but it may be indicative of<br />

something more profound<br />

the difference between er and ergens is relevant also in the context of the discussion of P-doubling<br />

in Flemish