Knowing Endangerment - Hanford Challenge

Knowing Endangerment - Hanford Challenge

Knowing Endangerment - Hanford Challenge

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Knowing</strong> <strong>Endangerment</strong>:<br />

WORKER EXPOSURE TO TOXIC VAPORS<br />

AT THE HANFORD TANK FARMS<br />

September 2003

The “Investigation of Events” chapter of the 2001 CH2M Hill <strong>Hanford</strong> Group (CHG) Conduct of Operations<br />

Manual states that a systematic investigation should occur when workplace conditions are abnormal or<br />

unexplained, or hazardous material limits are exceeded. According to CHG procedure, the investigation should<br />

involve collecting data on the initial conditions, taking statements from involved personnel, and obtaining computer<br />

printouts, copies of log books, work permits, and procedures. The actual responses to the event or abnormality<br />

should be documented and then compared to the expected responses, and detrimental effects of safety issues should<br />

be determined. Once the investigation and reconstruction of the event has occurred, the root cause(s) of the event<br />

should be determined, in order to preclude recurrence of the event. Ultimately, a final Investigation Report should<br />

be prepared, and distributed as a Lessons Learned to those who may benefit from the information.<br />

It is apparent that neither the U.S. Department of Energy nor CHG are willing to truly investigate the recent<br />

abnormal events occurring at the <strong>Hanford</strong> Nuclear Reservation in Eastern Washington, involving dozens of tank<br />

farm workers being exposed to toxic chemical vapors and requiring medical attention. The <strong>Hanford</strong> Joint Council, a<br />

mediation board responsible for investigating and resolving conflicts between workers and DOE contractors, was<br />

recently eliminated by the Department of Energy. Thus, the Government Accountability Project (GAP), at the<br />

request of several tank farm workers, has endeavored to conduct its own investigation, using CHG’s Investigation<br />

Criteria. GAP has compiled the following information through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests,<br />

through interviews with tank farm workers, health care providers, toxicologists, and others, and through review of<br />

incident reports, deposition testimony, Problem Evaluation Requests, Occurrence Reports, Lessons Learned,<br />

newsletters, newspaper stories, and other reports and background information provided to us and publicly available.<br />

Though the information presented below may not be exhaustive, for example, if information has been withheld<br />

through FOIA exemptions, it does form a minimum baseline of information from which it is possible to draw<br />

conclusions.<br />

It is GAP’s hope that this Investigation Report will trigger the DOE, CHG, and government policy makers to take<br />

swift and decisive steps to protect the health and safety of <strong>Hanford</strong>’s Tank Farm workers.<br />

This report was prepared by Clare Gilbert and Tom Carpenter of GAP’s Nuclear Oversight Campaign with<br />

assistance provided by interns Billie Morelli, Jessica Barkas, Susannah Dougherty, Archana Dayalu, GAP’s<br />

Jennifer Slagle, and Atis Muehlenbachs. GAP also thanks everyone who reviewed and commented upon drafts of<br />

the report.<br />

The Government Accountability Project (GAP) is a private, non-profit organization that advocates on behalf of<br />

employees who witness and disclose fraud, waste and abuse, mismanagement, threats to public and worker health<br />

and safety, and environmental violations. GAP has represented dozens of <strong>Hanford</strong> employees in various<br />

whistleblower lawsuits since 1998.<br />

Government Accountability Project<br />

Nuclear Oversight Campaign<br />

www.whistleblower.org<br />

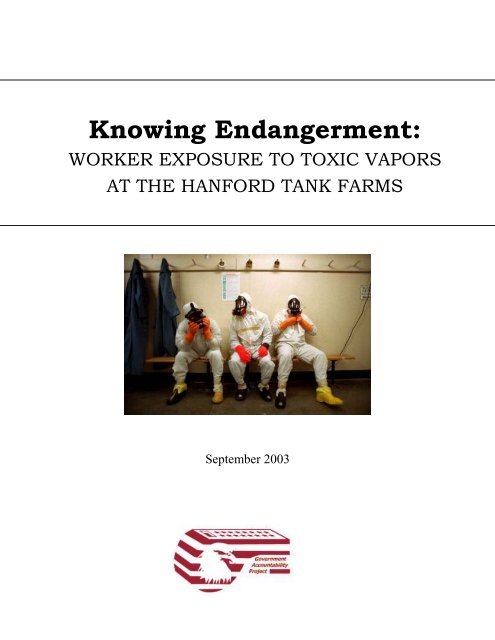

The photograph on the cover page was taken by Alan Berner of The Seattle Times<br />

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1<br />

II. BACKGROUND 4<br />

A. HANFORD TANK FARMS AND CHEMICAL VAPORS 4<br />

B. HEALTH EFFECTS OF TANK VAPORS 6<br />

EXPOSURES AND SYMPTOMS 6<br />

THE 1997 PNNL VAPOR REPORT 6<br />

C. HISTORICAL EXPOSURES AND RESPONSES 7<br />

THE 1992 DOE TYPE B INVESTIGATION 7<br />

THE HEWITT REPORT 8<br />

III. CURRENT CONDITIONS 10<br />

A. RECENT EXPOSURES 11<br />

B. CHEMICAL VAPOR MONITORING - CHG PROCEDURES AND PRACTICES 12<br />

MONITORING IN PROCEDURE 12<br />

MONITORING IN PRACTICE 13<br />

C. PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT – CHG PROCEDURES AND PRACTICES 19<br />

D. CHG RESPONSE TO CHEMICAL VAPOR EXPOSURES AND CONCERNS 23<br />

SUPPRESSED MONITORING DATA 25<br />

A CHILLED WORK ENVIRONMENT 28<br />

IV. HANFORD ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH FOUNDATION 29<br />

V. SYSTEMIC NATURE OF PROBLEM 35<br />

VI. REMEDIES AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS 38<br />

APPENDIX A: EXPOSURE EVENTS REQUIRING MEDICAL ATTENTION: 1987 - 1992 41<br />

APPENDIX B: EXPOSURE EVENTS REQUIRING MEDICAL ATTENTION: 2002 - 2003 42<br />

APPENDIX C: TANK VAPOR MONITORING EQUIPMENT 45<br />

iii

ACRONYMS<br />

> D Less than detectable level (on monitoring equipment)<br />

ACGIH American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists<br />

BHS Behavioral Health Services (at HEHF)<br />

CAS Chemical Abstracts Service<br />

CCC Command Control Center<br />

CCSI Contract Claims Services, Inc.<br />

CHG CH2M Hill, <strong>Hanford</strong> Group, Inc. (a DOE contractor)<br />

CT-ROSE Computed Tomography-Remote Optical Sensing of Emissions<br />

DOE United States Department of Energy<br />

DOE-RL US Department of Energy, Richland Field Office<br />

DST Double Shell Tank<br />

DRI Direct Reading Instrument<br />

FOIA Freedom of Information Act<br />

FY Fiscal Year<br />

GAP Government Accountability Project<br />

HAMTC <strong>Hanford</strong> Atomic Metal Trades Commission<br />

HASP Health and Safety Plan<br />

HAZWOPER Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response<br />

HEHF <strong>Hanford</strong> Environmental Health Foundation (a DOE contractor)<br />

HEPA High-Efficiency Particulate Air<br />

HLW High Level Waste<br />

HPT Health Physics Technician<br />

IDLH Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health<br />

IH<br />

Industrial Hygienist/ Industrial Hygiene<br />

IHT Industrial Hygiene Technician<br />

IME Independent Medical Examiner<br />

JHA Job Hazard Analysis<br />

Kadlec Local hospital in Richland<br />

L & I Labor and Industries (Workers Compensation)<br />

LEL Lower Explosive Limit (Flammable gas level)<br />

NCO Nuclear Chemical Operator<br />

NDMA n-nitrosodimethylamine<br />

NH 3 Ammonia<br />

NIOSH National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health<br />

NPO Nuclear Process Operator<br />

NWC Nuclear Weapons Complex<br />

OP-FTIR Open Path-Fourier Transform InfraRed<br />

OSHA Occupational Safety and Health Administration<br />

PAPR Powered Air Purifying Respirators<br />

PEL Permissible Exposure Limit<br />

PER Problem Evaluation Request<br />

PID Photo-ionization detector<br />

PNNL Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (operated by Battelle)<br />

PPE Personal Protective Equipment<br />

ppm Parts per million<br />

ppb Parts-per-billion<br />

ppbRAE RAE Systems parts per billion photo-ionization detector (PID) organics monitor<br />

iv

SCBA<br />

SST<br />

TLV<br />

TOC<br />

TWINS<br />

VOC<br />

WHC<br />

Self Contained Breathing Apparatus (or supplied air)<br />

Single-Shell Tank<br />

Threshold Limit Values<br />

Total Organic Carbon<br />

Tank Waste Information Network System<br />

Volatile Organic Compounds<br />

Westinghouse <strong>Hanford</strong> Corporation (a DOE contractor)<br />

v

KNOWING ENDANGERMENT:<br />

WORKER EXPOSURE TO TOXIC VAPORS AT THE HANFORD TANK FARMS<br />

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The <strong>Hanford</strong> Nuclear Reservation, located in southeastern Washington state, is a former nuclear<br />

weapons production facility owned by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), and operated under<br />

contract by private companies. The legacy of <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s plutonium production operations is a<br />

staggering quantity of deadly high-level radioactive and chemical byproducts, the worst of which, an<br />

estimated 53 million gallons of nuclear waste, are stored in 177 underground tanks. The tanks are<br />

arranged into eighteen farms, known as “tank farms,” and managed primarily by DOE contractor<br />

CH2M Hill <strong>Hanford</strong> Group, Inc. (CHG). The high level waste forms noxious vapors in the<br />

headspace of the tanks, which must vent through openings in the tanks to the atmosphere to prevent<br />

pressure buildup and possible explosion or tank rupture. This report focuses on the chemical vapors<br />

emitting from the high level waste tanks, the <strong>Hanford</strong> workers exposed to those vapors, and the<br />

willingness of the DOE and CHG to sacrifice worker health and safety in exchange for meeting<br />

“accelerated cleanup” deadlines at minimum financial cost.<br />

Over 1200 chemicals have been documented in the vapors contained within <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s tank<br />

headspaces, any number of which can and do escape through various tank equipment. Workers<br />

exposed to the tank vapors have suffered numerous health effects: nosebleeds, persistent headaches,<br />

tearing eyes, burning skin and lungs, coughing, difficulty breathing, sore throats, the need to<br />

constantly clear their throats, expectorating, dizziness, nausea, and increased heart rates. But the<br />

more serious health impacts may be long term in nature. DOE‟s Pacific Northwest National<br />

Laboratory (PNNL) concluded in a 1997 draft report that the risk of contracting cancer from<br />

exposure to these chemical vapors could be as high as 1.6 in 10.<br />

As DOE and CHG rush to pump and treat the high level waste to meet the DOE‟s new “accelerated<br />

cleanup” deadlines of faster, cheaper cleanup, worker exposures to chemical vapors have<br />

skyrocketed, with at least 45 documented chemical vapor exposure incidents involving over 67<br />

workers requiring medical attention between January 2002 and August 2003. There were an<br />

additional 75 complaints of tank vapor odors in the same time span.<br />

The DOE is conspicuously silent in the face of these rampant violations of worker health and safety.<br />

The lack of DOE oversight means that CHG is able to put on appearances of addressing the chemical<br />

vapor problem, without really making any significant changes:<br />

CHG‟s chemical vapor monitoring is woefully inadequate; its equipment can only<br />

accurately test for a small fraction of the over 1200 chemicals potentially coming out<br />

of the tanks and monitoring occurs only a small fraction of the time workers are in the<br />

field. CHG‟s recently acquired RAE Systems parts-per-billion (ppb) organics<br />

monitor was found to have such poor performance in tests for agent sensitivity that<br />

the U.S. Army discontinued testing of its ability to detect the presence of airborne<br />

chemical weapons.<br />

Despite knowledge of the soaring rate of chemical vapor exposures CHG refuses to<br />

let employees concerned about their own health and safety use supplied air<br />

respirators, and is, in fact, planning to reduce the amount of respiratory protection<br />

1

used in the tank farms and reduce the amount of administrative controls designed to<br />

protect workers. Already, CHG has done away with the “buddy system” whereby all<br />

work is performed in pairs, so that if one person is injured, there is another person on<br />

hand to provide assistance. CHG repeatedly has sent workers into known dangerous<br />

conditions wearing only dust masks as respiratory protection. The majority of<br />

workers in the <strong>Hanford</strong> tank farms wear no respiratory protection whatsoever.<br />

CHG either has intentionally falsified, covered-up, and skewed monitoring data or<br />

has maintained such haphazard chemical vapor monitoring procedures that the<br />

apparent falsifications and cover-ups are normal operating procedure. Excessively<br />

high contaminant readings on instruments frequently go unrecorded and<br />

unacknowledged by CHG, and health-affected tank farm workers are left with no<br />

dose record.<br />

CHG relies on an outdated, flawed 1996 report as a basis of several of its tank vapor<br />

monitoring and industrial hygiene practices, despite professional criticism that this<br />

report is no longer valid due to recent tank pumping and waste disturbances activities.<br />

Workers who raise concerns and insist on protecting themselves from chemical<br />

vapors have found themselves being denied overtime work, which can comprise over<br />

30% of a tank farm worker‟s annual income. They have been subjected to retaliation,<br />

harassment, and taunting by their peers and supervisors, which effectively creates a<br />

chilling atmosphere and discourages other workers from raising concerns.<br />

The <strong>Hanford</strong> Atomic Metal Trades Council (HAMTC), the bargaining agent representative of all<br />

unionized <strong>Hanford</strong> workers, recently considered withdrawing its support for CHG‟s Voluntary<br />

Protection Program (a DOE sponsored program that allows self regulation of worker health and<br />

safety), citing, among other things, a 300% increase in safety concerns in six months, “that<br />

employees feel cover-ups are taking place with limited critiques, no formal investigations or lessons<br />

learned,” and a “production over safety” environment created by CHG.<br />

Additionally, certain physicians and mental health counselors at the medical facility on site, the<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong> Environmental Health Foundation (HEHF), compound the problem for a tank farm worker<br />

seeking protection from chemical vapors. GAP has received several reports and documentation that<br />

HEHF management has:<br />

dismissed chemical vapor related symptoms as imagined or the result of allergies;<br />

designed policies of automatic referral to a mental health counselor for a host of<br />

questionable reasons;<br />

shredded and altered patients‟ progress notes;<br />

pressured workers to accept tank farm restrictions designed by tank farm contractors<br />

and suggested that the worker‟s job is at stake if they refuse;<br />

pressured HEHF health care providers not to write “recordable” medical restrictions<br />

for workers;<br />

prohibited patients from having a union steward, friend, or family member<br />

accompany them during medical visits.<br />

The 45 recent exposures in the past 20 months represent a 750% increase in the rate of similar<br />

exposures that triggered the last major DOE investigation into <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s chemical vapor exposures.<br />

When a former Assistant Secretary of Labor for OSHA reviewed that 1992 DOE Type B<br />

2

Investigation into 16 chemical vapor incidents requiring medical attention over a 55 month (4½ year)<br />

span, he commented that,<br />

The failure of those in responsible management charge to assign resources to this<br />

problem in the presence of repeated violations would, without any doubt, have been<br />

viewed by OSHA as willful violations of the [Occupational Safety and Health] Act<br />

and subject to possible criminal penalties. This conclusion would probably have been<br />

reached by the end of 1987 when three [worker exposure] episodes had occurred, but<br />

certainly by 1989 when the episodes reoccurred. The absence of high priority for<br />

solving this problem in 1990, with attendant lack of professional staff and resources<br />

could well put someone on trial for criminal behavior [had the occurrences been<br />

subject to OSHA enforcement and penalties]. Also, in 1989 with the reoccurrence of<br />

the episode, [an OSHA finding of] “imminent danger” and a series of restrictive<br />

procedures akin to closure of a manufacturing facility probably would have been<br />

invoked. 1<br />

Yet the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) does not have jurisdiction at the<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong> site or any other DOE site. Today, tank farm workers are left to fend for themselves as the<br />

DOE chooses not to exercise effective contractor oversight to ensure a quicker, cheaper „cleanup.‟<br />

In 2000, Congress enacted legislation in response to past injuries to workers at DOE sites such as<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong>. The legislation provides compensation to atomic workers in places like <strong>Hanford</strong> because of<br />

past exposures to radiation. Under this program, workers who can show that they were exposed to<br />

radiation and have contracted cancer can, in most instances, collect a one time payment of<br />

$150,000.00 and are eligible for lifetime medical care at taxpayer expense.<br />

This report documents that <strong>Hanford</strong> is in the process of creating a new generation of sick and injured<br />

workers. The de facto policy of placing production over safety that caused past ailments remains<br />

firmly in place at <strong>Hanford</strong>. And once again, workers are the ones who will have to live, and die, with<br />

the consequences of that policy.<br />

1 Morton Corn, Professor and Director, Division of Environmental Health Engineering, The Johns Hopkins<br />

University, School of Hygiene and Public Health, letter to T. O‟Toole, OTA, July 27, 1992, Cited in U.S. Congress,<br />

Office of Technology Assessment, HAZARDS AHEAD: MANAGING CLEANUP WORKER HEALTH AND SAFETY AT THE<br />

NUCLEAR WEAPONS COMPLEX 55-56 (OTA-BP-O-85) (Feb. 1993).<br />

3

II.<br />

BACKGROUND<br />

A. <strong>Hanford</strong> Tank Farms and Chemical Vapors<br />

High level nuclear waste (HLW) is recognized as one of the most dangerous substances known to<br />

humankind. It is created by processing irradiated nuclear reactor fuels in chemical solutions to<br />

recover plutonium for weapons production. In addition to being radioactive, HLW contains over one<br />

thousand chemicals. One Dixie cup full of HLW, placed in a crowded area such as a theatre, could<br />

kill nearly everyone within minutes. 2 The <strong>Hanford</strong> Nuclear<br />

Reservation (<strong>Hanford</strong>) stores 53<br />

million gallons of HLW in 149<br />

single shell and 28 double shell<br />

underground carbon steel storage<br />

tanks, ranging between 55,000<br />

and 1,000,000 gallon capacity<br />

and arranged in 18 groupings<br />

called „tank farms.‟ The HLW<br />

stored at the tank farms is<br />

chemically complex, due to the<br />

various reprocessing techniques<br />

and the wide array of substances<br />

added to the tanks over the<br />

years. 3 When irradiated fuel was<br />

reprocessed only shortly after<br />

irradiation, its waste liquid<br />

contained heat-generating<br />

radionuclides that made the<br />

waste so thermally hot that it<br />

would periodically burst into a<br />

violent surging boil that<br />

pressurized the tanks by<br />

releasing gases more than 20<br />

times the normal rate. Water<br />

was added to cool the waste. 4<br />

These various additions and the synergistic effects of the organic and inorganic chemicals and the<br />

radiation have transformed <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s HLW into a veritable “witches brew” of toxins. The waste in<br />

each tank forms varying mixtures of liquids and solids, including thick sludge, a dry, crystallized<br />

“saltcake,” liquid, and vapors. The tanks have to be monitored constantly. Probes detect leaks and<br />

measure temperatures, liquid levels, and other parameters associated with tank monitoring. There are<br />

risers that penetrate the tank dome and surrounding areas, and several process and service pits (called<br />

pump pits) are associated with the tanks. The pits are covered with heavy cover blocks and sealed<br />

2 Robert Alvarez, The Legacy of <strong>Hanford</strong>, THE NATION, Aug. 8, 2003, 31 – 35.<br />

3 Roy E. Gephart, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory [hereinafter PNNL], HANFORD: A CONVERSATION ABOUT<br />

NUCLEAR WASTE AND CLEANUP 5.16 (2002).<br />

4 Id.<br />

4

with foam. Waste routing equipment includes piping, pumps, valves, leak detection equipment,<br />

flexible jumper, and associated pump and valve pits. 5<br />

Because the chemical composition of <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s underground tanks is so<br />

dynamic in nature, the tanks are designed to vent in order to prevent excess<br />

vapors from over-pressurizing the tank head space and posing potentially<br />

serious safety consequences, such as explosions and fires. The single-shell<br />

tanks (SST) built before 1955 allow gases to vent to the atmosphere via<br />

breather “gooseneck” pipes. Thirteen of the SSTs and all of the double shell<br />

tanks were fitted with active ventilation systems and high-efficiency particulate<br />

air (HEPA) filters to remove particulates. 6 The remaining 136 of <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s<br />

SSTs are passively vented. 7 Vapors from these tanks are released at breaks in<br />

containment, breather filters, pump pits, saltwell pits, and other unsealed tank<br />

penetrations. Tank venting and chemical vapor exposures are influenced by the<br />

following: pumping or other waste intrusive activities; meteorological<br />

conditions (temperatures above 60 degrees F and changing barometric<br />

pressure); height of liquid in tank; hydrogen/flammable gas concentration; and<br />

activities conducted by tank farm employees (opening cabinets, pit entry,<br />

turning valves, flushing, performing monitoring phase). 8 Most reports of odor<br />

problems and exposure to chemical vapors and gases occur in the single shell<br />

tank farms, since they are older, not as well contained, and have passive breather filters. 9<br />

“<strong>Hanford</strong> waste tanks are, in<br />

effect, slow chemical<br />

reactors in which an<br />

unknown but large number<br />

of chemical (and<br />

radiochemical) reactions are<br />

running simultaneously.<br />

Over time, the reaction<br />

dynamics and compositions<br />

have changed and will<br />

continue to change . . . .”<br />

- Art. Janata et. al, REPORT OF THE AB<br />

INITIO TEAM FOR THE HANFORD TANK<br />

CHARACTERIZATION AND SAFETY ISSUE<br />

RESOLUTION TEAM , cited in Gephart,<br />

HANFORD: A CONVERSATION<br />

ABOUT NUCLEAR WASTE AND<br />

CLEANUP 5.16<br />

The limited tank headspace sampling that has been conducted demonstrates that the headspace<br />

vapors may contain any number of over 1200 different organic and inorganic chemicals, in addition<br />

to radiation. 10 Chemicals potentially venting from the tanks include: carcinogens such as radioactive<br />

particles, benzene, chloroform, and potential carcinogens, such as n-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA),<br />

acetone-trile, carbon tetrachloride, and ethylene-dibromide (the last 4 of which are also liver toxins).<br />

Other toxic compounds present include: ferrocyanide, hydrogen-sulfide, hydrogen-cyanide, sulfurdioxide,<br />

sulfur-trioxide, hydrogen-fluoride, nitrous-oxide, hydrazine, butanol, acetone, hexane,<br />

xylene, carbon monoxide, methylamine, and ammonia. 11 Methylamine smells like ammonia, but is<br />

5 Don Quilici, CIH, CSP, Baseline Hazard Assessment: <strong>Hanford</strong> Tank Farms 2003 E / 200 W Areas, 42 (Submitted<br />

to Westinghouse <strong>Hanford</strong> Company, Contract No. MJG-SCV-165890) (Oct. 15, 1993).<br />

6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY – RICHLAND FIELD OFFICE [hereinafter DOE-RL], TYPE<br />

B INVESTIGATION OF HANFORD TANK FARM VAPOR EXPOSURES 3-2 (April 1992) [hereinafter 1992<br />

TYPE B INVESTIGATION].<br />

7 CH2M HILL HANFORD GROUP [hereinafter CHG], TANK FARMS HEALTH AND SAFETY PLAN 30<br />

(HNF-SD-WM-HSP-002, Rev. 4) (Mar. 2002) [hereinafter HASP].<br />

8 Kathie Lavaty, Prezant Associates, Report Of CH2M Hill <strong>Hanford</strong> Group Tank Vapor Concern Evaluation, March<br />

11 Through March 29, 2002 Observations, Discussion And Recommendations, 10 (April 11, 2002).<br />

9 PNNL, HANFORD ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH FOUNDATION [hereinafter HEHF], EXPOSURE-BASED<br />

HEALTH ISSUES PROJECT REPORT: PHASE I OF HIGH-LEVEL WASTE TANK OPERATIONS,<br />

RETRIEVAL, PRETREATMENT, AND VITRIFICATION EXPOSURE-BASED HEALTH ISSUES ANALYSIS<br />

6.1 (PNNL-13722) (Nov. 2001).<br />

10 L.M. Stock & J.L. Huckaby, PNNL, A SURVEY OF VAPORS IN THE HEADSPACES OF SINGLE-SHELL<br />

WASTE TANKS, 4 (PNNL-13366) (Oct. 2000); See also, The Tank Waste Information Network System (TWINS)<br />

database, which contains tank waste and vapor characterization information on all the <strong>Hanford</strong> Tanks, available at<br />

http://twinswe.pnl.gov. Visitors to the TWINS database must first submit an application to DOE at<br />

Melvin_R_Adams@rl.gov, and identify name, organizational affiliation, phone number, email address, and the<br />

reason for requesting access.<br />

11 CHG, HASP, supra note 7, at 9.<br />

5

not detected on an ammonia monitor. These and hundreds more chemicals can be released into the<br />

workers‟ breathing environment via tank venting. 12<br />

B. Health Effects of Tank Vapors<br />

Workers exposed to<br />

tank vapors experience<br />

health effects such as<br />

nosebleeds, persistent<br />

headaches, tearing eyes,<br />

sticky eyes, burning<br />

skin, contact dermatitis,<br />

increased heart rate,<br />

difficulty breathing,<br />

coughing, sore throats,<br />

constant need to clear<br />

throats, expectorating,<br />

dizziness, nausea, and<br />

metallic taste in mouth<br />

and on lips.<br />

Exposures and Symptoms<br />

The chemical vapors emanating from the <strong>Hanford</strong> tanks have various described odors: ammonia,<br />

rotten eggs, wine, old socks, musty, diaper pail, garlic, whisky, gasoline, wet cardboard, mint, fruit,<br />

chloroform, and butter. Other chemicals coming off the tanks have no odors at all, such as n-<br />

nitrosmethanamine (a carcinogen and liver toxin), propane, propene (asphyxiant),<br />

trichlorofluoromethane (asphyxiant), nitrous oxide, and carbon monoxide (poison).<br />

The symptoms of workers exposed to tank vapors may best be<br />

illustrated in case studies of a few tank farm workers. One worker was<br />

exposed for approximately twenty minutes to high levels of what his<br />

co-workers described as an ammonia odor, though he could not smell it<br />

as he had a head cold. When he left the area, all of his exposed skin<br />

immediately became bright red and he had a putrid, metallic taste in his<br />

mouth. He later suffered a sore throat and vocal cords, recurring<br />

nosebleeds, and the need to constantly clear his throat. He suffered a<br />

series of headaches and for five months his “lungs just wept,” coughing<br />

up a white, milky substance, his voice underwent a permanent change,<br />

and he woke up in the middle of the night in severe respiratory distress<br />

and was rushed to the emergency room for treatment.<br />

Another worker suffered five separate vapor exposures between<br />

January and February 2002. He describes opening cabinets attached to<br />

tank piping, only to be overcome by vapors that were so powerful he<br />

stumbled backwards and had trouble inhaling. This worker suffered burning nasal passages,<br />

nosebleeds, a metallic taste on his lips, rashes, welts, and contact dermatitis which took several<br />

months to heal with prescription medication. Since these exposures he has become sensitive to<br />

gasoline, bleach, ammonia, some paints and deck stain.<br />

Yet another worker‟s 2002 exposures resulted in burning sinuses, nosebleeds, sore throat, hoarseness,<br />

tearing eyes, nausea, dizziness and increased heart rate. Three physicians each separately concluded<br />

that his sinus problems and nosebleeds were the likely result of his exposures to tank vapors.<br />

The 1997 PNNL Vapor Report<br />

In 1997, Battelle's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) issued to DOE a draft report<br />

examining the potential health risks associated with the vapors released from a single <strong>Hanford</strong> tank,<br />

C-103. 13<br />

12 Id. at 9 - 10.<br />

13 A. D. Maughan, J.G. Droppo, K.J. Castleton, PNNL, HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT FOR SHORT- AND<br />

LONG-TERM WORKER INHALATION EXPOSURE TO VAPOR-PHASE CHEMICALS FROM THE SINGLE-<br />

SHELL TANK 241-C-103, DRAFT (Mar. 1997) [hereinafter 1997 C-103 VAPOR HEALTH RISK<br />

ASSESSMENT]<br />

6

The PNNL report examined emissions from Tank C-103 and found that 221 gases released from C-<br />

103 were identified from the <strong>Hanford</strong> Tank Waste Information Network System (TWINS). The goal<br />

of the study was to determine the health risks from inhalation of the vapors exhausted from two<br />

exhauster tank stack configurations (one bent at the top and one straight stack) and whether worker<br />

exposures to the tank‟s chemical vapors were within OSHA guidelines. 14<br />

The PNNL study identified major uncertainties in knowledge pertaining to<br />

toxicity effects of many of the chemicals detected in the tank. The report<br />

emphasizes the synergistic effects of the chemicals upon each other,<br />

asserting that “many of the vapor-phase chemicals are in a volatile, reactive<br />

state” and that “the potential for synergism increases exponentially with the<br />

number of compounds making up the exposure.” 15 According to the report,<br />

tank farm workers<br />

may be at potentially greater risk than is commonly held for the<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong> Site. The scenario becomes more realistic as the<br />

maintenance of tank chemicals shifts to remediation. It is further<br />

unclear whether cancer is induced after chronic exposure or<br />

perhaps after a single release. In any case, because the latent<br />

period for manifesting most forms of cancer is approximately 20<br />

years, it will be unlikely that the etiology will be traced to any<br />

given event. 16<br />

The PNNL scientists<br />

concluded that the risk<br />

of contracting cancer<br />

from exposure to the<br />

chemical vapors from<br />

tank C-103 could be as<br />

high as 1.6 in 10, and<br />

that even this estimate<br />

“may not represent the<br />

highest potential risks.”<br />

They further asserted<br />

that if other nearby<br />

tanks were to vent to the<br />

outside, which all<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong> tanks do, then<br />

“the risks would be<br />

increased.”<br />

The report went on to state that while a tank worker may not receive a chemical vapor dose in excess<br />

of OSHA regulations (because of OHSA‟s methodology for determining exposures to mixtures of<br />

chemicals), “the worker would be at risk of developing cancer, or other chronic disease, from the<br />

exposure.” 17<br />

C. Historical Exposures and Responses<br />

The 1992 DOE Type B Investigation<br />

In the 55 months between July 1987 and January 1992, there were 16 incidents where tank farm<br />

workers were exposed to chemical vapors and required medical attention (see Appendix A). This<br />

series of events triggered investigations by the U.S. Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, the<br />

DOE‟s Office of Environment, Safety and Health, DOE‟s Office of Inspector General, and, upon<br />

invitation, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). 18 These investigations found<br />

that DOE contractors were failing to provide adequate worker protection after repeated internal<br />

14 Id.<br />

15 Id. at 7.2.<br />

16 Id. (emphasis added).<br />

17 Id. at 8.1.<br />

18 Robert Alvarez, Professional Staff, U.S. Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, Memorandum to Files,<br />

Environmental, Safety and Health Issues at the U.S. Department of Energy’s <strong>Hanford</strong> Site, April 10, 1993.<br />

7

warnings by safety experts, threatening workers with job loss if they reported injuries, and knowingly<br />

submitting false information regarding lost-time injuries. 19<br />

The 16 exposures also triggered a large scale investigation by the DOE and culminated in a highlevel,<br />

comprehensive Type B Investigation of <strong>Hanford</strong> Tank Farms Vapor Exposures, released in<br />

April of 1992. 20 The Type B Investigation found numerous problems underlying the then primary<br />

tank farms contractor‟s (Westinghouse <strong>Hanford</strong> Corporation (WHC)) inability to protect its tank<br />

farm workers, and concluded there were 37 “judgments of need” to be translated into corrective<br />

action. 21 The Type B Investigation resulted in the implementation of supplied air for workers at 84<br />

of the 177 tanks, constant air monitoring by Industrial Hygiene Technicians (IHT) at all sites where<br />

supplied air was not being used, requirements to characterize of tank contents and vapors, the<br />

creation and implementation of a tank farms Health and Safety Plan (HASP), and a plan to install<br />

permitted ventilation on single shell tanks. Reports of exposures decreased as a result of the<br />

implementation of these controls. Unfortunately, this did not last long.<br />

The Hewitt Report<br />

In July 1996, Westinghouse released a report, Tank Waste Remediation System Resolution of<br />

Potentially Hazardous Vapors Issue, authored by an employee named Elton Hewitt. 22 The Hewitt<br />

report concluded that due to implementation of controls around potential vapor release points,<br />

characterization of tank contents and vapors, and “as a result of better communications regarding<br />

vapor odors and risks” following the Type B Investigation, “employee exposure incidents have<br />

virtually ceased” and the vapor problem had been “resolved.” 23<br />

In reaching this conclusion, Hewitt noted that while ammonia and nitrous oxide compounds routinely<br />

were present in concentrations greater than 5 times permissible exposure limits (PELs) in the<br />

headspace of tanks, when vented, they did not pose a hazard to workers because barriers had been<br />

installed around release points and effective controls were in place. The report went on to assert that<br />

even if control measures failed, because ammonia has such a distinct odor and can be smelled at<br />

levels below the PEL, employees could leave the area before any overexposures occurred. 24<br />

Additionally, while acknowledging that “potential carcinogens have been identified as being present<br />

in the tank headspace,” Hewitt postulated that<br />

these chemicals are present at sufficiently low concentrations so that employees can<br />

be protected from overexposure by maintaining their ammonia exposure level below<br />

its PEL [25 ppm]. By protecting employees from an excess exposure to ammonia,<br />

the resulting exposure to other materials would also be at acceptable levels. 25<br />

19 Id.<br />

20 DOE-RL, 1992 TYPE B INVESTIGATION, supra note 6.<br />

21 Id. at 5.15 – 5.19.<br />

22 Elton R. Hewitt, et. al., WESTINGHOUSE HANFORD COMPANY [hereinafter WHC] , TANK WASTE<br />

REMEDIATION SYSTEM RESOLUTION OF POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS VAPORS ISSUE (WHC-SD-TWR-RPT-001) (June<br />

24, 1996) [hereinafter HEWITT REPORT].<br />

23 Id. at 2.<br />

24 Id. at 17.<br />

25 Id. at 7-8.<br />

8

As a result of Hewitt‟s conclusions, the use of supplied air as a precautionary measure was<br />

eliminated entirely at the <strong>Hanford</strong> tank farms. 26 The Hewitt report continues to guide CHG‟s<br />

industrial hygiene practices today, 27 to the point where workers cannot use supplied air even if they<br />

specifically request to do so because they have smelled, tasted, or suffered adverse health effects<br />

from these invisible vapors that are increasingly inundating the tank farms.<br />

There are many obvious flaws with the Hewitt report. First, Hewitt brushes aside the threats of<br />

carcinogens venting off of the tanks, by asserting that they are minimal and workers can be protected<br />

from them by protecting workers from ammonia. But ammonia is an inorganic chemical, while<br />

many of carcinogens venting from the tanks are organics, such as benzene. Relying on ammonia<br />

monitoring equipment and detection properties to protect workers from organic carcinogens is<br />

illogical.<br />

Second, by focusing on only ammonia and nitrous oxide, Hewitt downplays the synergistic effect of<br />

all the chemicals, brushes aside the significance of the carcinogens venting from the tanks, and<br />

ignores the fact that many of the constituents in the chemical vapors are unknown and not<br />

toxicologically profiled.<br />

Third, relying on workers sense of smell to protect them from toxic vapors is flawed and<br />

irresponsible for several reasons:<br />

Not only ammonia vents from the tanks, but also organics which may not have a<br />

characteristic odor. Carbon monoxide is a deadly poison, which has no odor at<br />

all. Likewise, NDMA is known to vent from the tanks, has no distinct odor, and<br />

is a potential carcinogen that also causes liver damage. 28<br />

Ammonia and organics may vent at different times, meaning that even if workers<br />

left the area when they smelled ammonia, they may not do so when other<br />

compounds vent from the tanks.<br />

By the time a worker identifies a tank vapor such as ammonia, they may have<br />

already been exposed to toxicants within the vapor that could be causing<br />

biological damage to their bodies. <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s exposure limit for ammonia is 25<br />

ppm; a person generally cannot identify that what they are smelling is ammonia<br />

until its ambient concentration reaches a level of at least 50 ppm. 29<br />

Workers may not smell the ammonia concentrations for a variety of reasons, such<br />

as acclimatization to the odor when the level slowlys increase, olfactory fatigue<br />

when the level is too high to smell (such as when levels concentrate in confined<br />

or closed spaces), or nasal congestion.<br />

26 Jim Jabarra, CHG, Chemical Vapors Solution Team, Formal written answer to question #5 from tank farm<br />

workers, July 2002.<br />

27 Id.<br />

28 CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL [hereinafter CDC], TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR N-<br />

NITROSODIMETHLYAMINE, CAS# 62-75-9, section 1.1, December 1989, available at<br />

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/phs141.html;<br />

29 CDC, TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR AMMONIA, CAS# 7664-41-7, section 1.3, September 2002, available at<br />

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles.phs126.html; John Harte, et. al., TOXICS A TO Z: A GUIDE TO EVERYDAY<br />

POLLUTION HAZARDS 216 (1991). These sources indicate that while ammonia‟s odor detection threshold can be as<br />

low as 5 ppm, ammonia‟s odor recognition threshold is 50 ppm.<br />

9

Not only does the science of the Hewitt report appear fundamentally flawed, but Hewitt‟s assertions<br />

that “employee exposure incidents had virtually ceased” and that the vapor problem had been<br />

“resolved” were rendered invalid within a matter of months. In August of 1997, GAP released a<br />

White Paper examining negligent exposures to workers at one particular <strong>Hanford</strong> tank – Tank C-103.<br />

The tank has a history of emitting toxic, cancer-causing vapors into the atmosphere. GAP revealed<br />

that, by the time of GAP‟s report, vapor emissions had resulted in over a dozen known worker<br />

exposure incidents from this tank alone. 30<br />

Finally, a consultant to CHG regarding the 2002-2003 vapor exposure incidents pointed out the flaw<br />

of relying upon the Hewitt report now that the conditions in the tanks have changed due to ongoing<br />

pump and treat activities:<br />

The [Tank Vapor] Industrial Hygiene Personal Monitoring Program Plan . . . appears<br />

to be based, to a large part, on conclusions reached in the 1996 [Hewitt report]. As<br />

noted above, data recently collected . . . indicates that the concentration of selected<br />

organic compounds has increased relative to data collected in 1995. Current pumping<br />

activities were not underway during the period that this data was collected and recent<br />

TDU sampling results suggest a need to evaluate what, if any, these activities might<br />

be having on tank vapor constituents and concentrations. 31<br />

III.<br />

CURRENT CONDITIONS<br />

In the last two years, many circumstances of <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s operations have changed considerably when<br />

compared with those when the Hewitt Report was released in 1996. First and foremost, the <strong>Hanford</strong><br />

tank farms are subjected to an “accelerated cleanup” schedule imposed by the Bush Administration.<br />

The DOE‟s current plan is to transfer most of the solid and liquid radioactive wastes from at least 26<br />

single-shell tanks into double-shell tanks by 2006, and then seal or “close” those tanks. The current<br />

pumping and other waste intrusive activities cause higher rates of vapor release events as the waste is<br />

stirred and transferred at high pressure from tank to tank.<br />

These current activities affect tank farm operations in two main ways. First, as the waste is disturbed<br />

more opportunities are created for vapor releases, potentially exposing workers to the chemical<br />

vapors. Second, as the waste is transferred from tank to tank, the chemical makeup of the vapors<br />

changes, rendering previous tank vapor characterization invalid. CHG has not taken seriously<br />

enough the risks that both of these factors pose to the health and safety of tank farm workers.<br />

In addition to increases in chemical vapor exposures, the rush toward accelerated cleanup also has<br />

resulted in 6 contamination events involving 17 individuals since January 2002. Several of these<br />

incidents involve workers who came in direct contact with tank waste, while others involve<br />

contamination by radioactive dust and cesium.<br />

In an April 22, 2002 letter to CHG threatening to withdraw support for the Voluntary Protection<br />

Program, the <strong>Hanford</strong> Atomic Metal Trades Council (HAMTC), the collective bargaining agent for<br />

<strong>Hanford</strong>‟s unionized workers, maintained that CHG‟s acceptance of an “accelerated cleanup<br />

30 Government Accountability Project, BLOWING OFF SAFETY AT THE HANFORD TANK FARMS: TOXIC NEGLIGENCE<br />

AT TANK 103-C, August 1997, at http://www.whistleblower.org; John Stang, <strong>Hanford</strong> Waste Tank Blasted By<br />

Group, TRI-CITY HERALD, Aug. 12, 1997.<br />

31 Kathie Lavaty, supra note 8, at 7.<br />

10

schedule with DOE-ORP [Office of River Protection] . . . has increased safety risk to workers and the<br />

environment.” 32 HAMTC also criticized the following behavior by CHG:<br />

“Loss of control outside radiological / contamination boundaries. Example:<br />

244A changing wind speed restrictions from 10 mph to 25 mph; historically<br />

10 mph proved less chance for spread of contamination;”<br />

“Accepting risks while exposing workers and the environment to known /<br />

unknown hazards based on the graded approach;”<br />

“300% increase in the number of safety concerns during the last six months.<br />

Exempt and professional staff are also contacting HAMTC with their<br />

concerns;”<br />

“Numerous violations, incomplete work packages, no review of USQ‟s while<br />

proceeding in the face of uncertainty. At the same time, doing away with the<br />

two-man rule, safety equipment is out of calibration and still used.”<br />

According to HAMTC, workers report that “it‟s production over safety.” 33<br />

A. Recent Exposures<br />

GAP has found evidence of 45 chemical vapor exposure events requiring medical attention for at<br />

least 67 people in the 20 months between January 2002 and August 2003. 34 (see Appendix B). There<br />

were at least an additional 75 chemical vapor odor complaints in the same time period. This sharply<br />

contrasts with the 16 exposure events requiring medical attention in the 55 months between July<br />

1987 and January 1992, and amounts to a 750% increase in the rate of significant chemical vapor<br />

exposures.<br />

CHG‟s written policy is that any employee who experiences any type of<br />

symptoms from chemical vapor exposures, such as watering eyes,<br />

burning nose, or headache, is required to notify their supervisor and<br />

report to the nearest HEHF first aid station. 35 When employees just smell<br />

an odor, and do not experience physical symptoms, they are not required<br />

to report to HEHF. GAP has received several reports though, that<br />

numerous tank farm workers experience symptoms such as headaches,<br />

nosebleeds, and metallic taste, but do not report to HEHF for fear of<br />

reprisal or fear of being perceived as troublemaker or as not a team<br />

player.<br />

Of the 45 documented chemical vapor exposure events requiring medical<br />

attention since January 2002, workers have experienced the following<br />

Between January 2002<br />

and August 2003,<br />

workers described the<br />

vapor odors they<br />

encountered in the<br />

following terms:<br />

ammonia, chemical-like,<br />

chlorine, creosote,<br />

diesel-like, foul, musty,<br />

obnoxious, onion, rotten<br />

egg, smoky, unfamiliar,<br />

wet cardboard, and as a<br />

“whiff of organics.”<br />

32 Signed Letter from Tom Schaeffer, President of the <strong>Hanford</strong> Atomic Metal Trades Commission, to Edward<br />

Aromi, President of CHG, dated April 22, 2003. Written on the front of the letter is “HOLD DO NOT RELEASE 4-<br />

23-03 13:15 JJJ.” [hereinafter HAMTC Letter].<br />

33 Id.<br />

34 This number includes only medical attention required by worker exposure to chemical vapors coming off of the<br />

high level waste tanks. This number does not include a worker smelling an odor without experiencing symptoms,<br />

and does not include non-vapor-exposure events requiring medical attention, such as exposure to or contact with<br />

liquid tank waste, or personal medical conditions that resulted in HEHF visits.<br />

35 CHG, HASP, supra note 7, at 41-42<br />

11

symptoms: burning skin, persistent rash on face, burning nasal passages, burning, running eyes, dry,<br />

productive or persistent coughs, persistent sore or scratchy throat, damaged vocal cords, instant or<br />

persistent headache, metallic taste in mouth, nosebleeds (one lasting for over 20 minutes), nausea,<br />

vertigo, shortness of breath, and increased heart rates.<br />

The chemical vapor exposure events requiring medical attention since January 2002 occurred in the<br />

following tank farms, followed by the number of separate events that occurred there: C Farm (11);<br />

AW Farm (8); AN Farm (7); A Farm (5); BY Farm (3); AP Farm (2); SX Farm (2); U Farm (3); SY<br />

Farm (1); AX Farm (1); AZ Farm (1); Unknown (1).<br />

B. Chemical Vapor Monitoring - CHG Procedures and Practices<br />

Monitoring in Procedure<br />

CHG uses a variety of equipment to monitor for chemical vapors coming off of the high level waste<br />

tanks, and conducts monitoring activities at several different locations.<br />

CHG conducts monitoring activities at several different locations for chemical vapors coming off of<br />

the high level waste tanks. Headspace monitoring (in the dome or vapor space of the tank) is<br />

performed by lowering a probe into the headspace through a portal to determine the potential for<br />

vapor release and to identify and quantify the chemicals in each tank. 36 Source monitoring is<br />

intended to take place close to the source of vapors, such as at exhausters, pump pits, and electrical<br />

cabinets. The data is to be used by industrial hygiene to determine the highest potential levels at<br />

which employees could be exposed. 37 Area<br />

monitoring, also called breathing zone monitoring,<br />

involves collection and analysis of samples in the<br />

general area where personnel work. 38 Personal<br />

monitoring consists of attaching various sampling<br />

devices to an employee during their work tasks and<br />

evaluating any determinant exposures. 39 CHG‟s new<br />

personal ammonia monitor is an example of personal<br />

monitoring; it is worn on the worker‟s clothing and<br />

changes color according to the intensity of the<br />

ammonia exposure the worker is receiving. 40<br />

CHG uses a variety of equipment to monitor for<br />

chemical vapors coming off of the high level waste<br />

tanks. Each instrument available to perform this monitoring is sensitive to varying numbers of<br />

specific chemicals. 41 No one specific monitor is required to detect a particular class of contaminant.<br />

36 Id. at 47.<br />

37 Id. at 46.<br />

38 Id.<br />

39 Id.<br />

40 CHG, Winds Of Change: Weekly Operational Changes, Mar. 6, 2003, Issue 37, p. 1 [hereinafter Winds of<br />

Change].<br />

41 Upon review of a sample of CHG‟s Direct Reading Instrument Survey records, GAP determined that CHG used at<br />

least 8 separate pieces of monitoring equipment (different pieces on different days for different contaminants) during<br />

November and December 2002.<br />

12

The most recently acquired and most commonly used Direct Reading Instrument (DRI) monitoring<br />

equipment used by CHG includes: portable colorimetric ammonia badges, SUMMA canisters, and<br />

hand-held ppbRAE organics readers that present results in parts-per-billion. 42 Some monitoring<br />

results are provided in real time measurements, such as with the ammonia badge or hand held<br />

monitors that instantly display contaminant levels. Other monitoring involves collecting samples and<br />

sending the samples to a laboratory to determine the contaminant levels in the air, such as with<br />

SUMMA canisters.<br />

From the over 1200 chemicals potentially venting from the tanks, CHG has identified 10 primary<br />

potential exposure chemicals as ammonia, nitrous oxide, benzene, butanol, acetone, hexane, xylene,<br />

hydrogen, acid gases, and sulfur containing compounds. CHG asserts that “ammonia is a primary<br />

constituent of concern.” 43<br />

Before any new tank-farm job begins, the industrial hygienist (IHT) conducts a job hazard analysis<br />

(JHA) by considering the location of the work, type of work to be performed, available<br />

characterization data, and source and area monitoring results in order to determine potential<br />

hazards. 44 According to CHG‟s health and safety plan (HASP), the levels of monitoring should<br />

occur as follows:<br />

If source monitoring conducted during the JHA indicates that concentration of<br />

organics exceeds 2 ppm, or ammonia exceeds 25 ppm, then the workers‟ breathing<br />

zone must be monitored while the work is being performed.<br />

If any organics are detected above 2 ppm, or ammonia above 25 ppm, in the<br />

workers‟ breathing zone, then the workers are required to wear a full face cartridge<br />

respirator.<br />

If levels in the breathing zone exceed 25 ppm organics or 300 ppm ammonia, then<br />

conditions are considered immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH), and the<br />

work area must be evacuated or supplied air must be used. 45<br />

Depending on the workplace conditions identified in the JHA, various controls may be put in place:<br />

engineering (i.e. use of a glove bag or an exhauster), administrative (i.e. establishment of barricaded<br />

areas or requirements that all work be done in pairs), or use of personal protective equipment (i.e.<br />

respirators). 46<br />

Monitoring in Practice<br />

GAP‟s investigation has found several flaws in CHG‟s current monitoring procedures and practices.<br />

These problems place tank farm workers at risk of unnecessary and dangerous exposures to chemical<br />

vapors.<br />

1. Limitations of Monitoring Equipment and Methods<br />

42 CHG, Winds of Change, supra note 40.<br />

43 CHG, HASP, supra note 7 at 9.<br />

44 Id. at 26, 46.<br />

45 Id. at 32-34, Table 2-4.<br />

46 CHG, HASP, supra, note 7, at 10.<br />

13

CHG‟s monitoring equipment has limited capabilities to detect hazards in the workplace<br />

environment, especially since many of the chemicals in the vapors are unknown and uncharacterized.<br />

Most of the sampling that has occurred on the tank headspaces is over seven years old. 47 Very little<br />

characterization of vapor space monitoring has occurred since the recent “accelerated cleanup”<br />

activities began. Only 11 tank headspaces have been sampled since 1999, and none of those<br />

occurred in 2002 or 2003. 48 As retrieval operations disturb and change the chemical constituents in<br />

the tank, monitoring of tank vapors must be revised and readjusted to reflect what is really in the<br />

tanks. One senior industrial hygienist for CHG recently admitted that there are unknown chemicals<br />

and compounds emitted from the tanks that cannot be tested for with CHG‟s monitoring equipment. 49<br />

Even if all the chemicals coming off the tanks are identified and characterized, most of CHG‟s air<br />

monitoring instruments can detect only a handful of compounds at one time, out of potentially 1200<br />

chemicals present in the vapors. 50 The instruments can only be calibrated to a few compounds at a<br />

time and within a certain range (see Appendix C).<br />

There are additional technical problems with the equipment. For example, CHG‟s recently acquired<br />

RAE Systems parts-per-billion photo-ionization organics monitor (ppbRAE) was found to have such<br />

“poor performance” in tests for agent sensitivity that the U.S. Army discontinued testing of this<br />

detector‟s ability to detect the presence of certain organic chemicals; specifically, airborne chemical<br />

weapons. 51 The ppbRAE had reduced sensitivity with increasing use, as the UV lamps used to ionize<br />

the vapor samples for detection were easily contaminated by dust, dirt, moisture, and other exposure<br />

residue. Frequent and thorough cleaning was needed to maintain detector performance. The report<br />

questioned the reliability of the ppbRAE, citing among other things, the need for frequent recalibration,<br />

the wide range of response factors observed, and its inability to detect some tested<br />

chemicals even at IDLH levels. 52<br />

Prior to acquiring the ppbRAE, CHG used the “580-EZ” to perform much lower explosive limit<br />

(LEL) and total organic compounds (TOC) 53 monitoring until late 2002. 54 The 580-EZ was<br />

manufactured to detect a few specific TOCs as well as ammonia. However, this instrument is known<br />

47 See TWINS database, supra note 10.<br />

48 May 6, 2003 letter from Mary Beth Burandt, DOE-RL, to Clare Gilbert, Government Accountability Project,<br />

responding to a request for information on tank waste characterization. 03-ORP-049.<br />

49 [Industrial Hygiene] Senior Safety Manager, CH2M Hill <strong>Hanford</strong> Group, Sworn Deposition in connection with<br />

Stone, et. al. v. CH2M Hill <strong>Hanford</strong> Group, filed with the Department of Labor, May 7, 2003, pg. 62 [hereinafter IH<br />

Deposition].<br />

50 L.M. Stock & J.L. Huckaby, supra note 10.<br />

51 Teri Longworth and Kwok Y. Ong, United States Army, Soldier and Biological Chemical Command, DOMESTIC<br />

PREPAREDNESS PROGRAM: TESTING OF RAE SYSTEMS PPBRAE VOLATILE ORGANIC COMPOUND (VOC) MONITOR<br />

PHOTO-IONIZATION DETECTOR (PID) AGAINST CHEMICAL WARFARE AGENTS, SUMMARY REPORT, ECBC-TR,<br />

September 2001, pg. 16, available at http://www2.sbccom.army.mil/hld/downloads/reports/ppbrae_final.pdf<br />

52 Id. at 12-16.<br />

53 GAP has consulted several representatives from various companies that manufacture and sell monitoring<br />

equipment used by CHG, and very few seem to know what TOC stands for. CHG asserts that it stands for Total<br />

Organic Compounds. Some company representatives assert that it stands for Total Organic Carbons. Still other<br />

experts assert that it stands for Toxic Organic Compounds. For purposes of this report, GAP assumes it means<br />

“Total Organic Compounds,” though what exactly that entails, we are still not sure.<br />

54 CHG still relied on the 580-EZ as of December 2002, although less frequently than in previous months. Most<br />

CHG DRI surveys for 2002 list the 580 EZ as the instrument used in its TOC monitoring surveys.<br />

14

to have significant detection problems, and is not even recommended by the company‟s sales<br />

representatives. 55<br />

There are also considerable time and space limitations<br />

to monitoring for chemical vapors in the tank farms.<br />

Monitoring coverage of potential exposures occurs at<br />

only a tiny fraction of the time a tank farm worker is<br />

in the field. According to experts consulted by GAP,<br />

even if CHG were able to monitor for all 1200 of the<br />

chemicals in the tanks, it would still only be<br />

monitoring 10% of a worker‟s potential exposures.<br />

With 136 passively vented tanks, each with numerous<br />

vapor release points, it is virtually impossible to<br />

physically monitor all potential exposures. 56 When<br />

monitoring takes place after the exposure has<br />

occurred, which often happens anywhere from one 57<br />

to several hours 58 after the exposure incident, the<br />

monitoring yields zero protection for the worker.<br />

Additionally, because the human body is several orders of magnitude more sensitive than vapor<br />

monitoring equipment, it is possible for humans to sense contaminants that the equipment is<br />

incapable of registering – not because contaminant levels are too low for the machines to detect, but<br />

because levels come in quick bursts 59 that sometimes are not consistent enough in time to be detected<br />

by monitoring equipment. The significance of this can be explained by examining ammonia, one of<br />

CHG‟s “primary constituents of concern.” Humans can identify ammonia at two thresholds. It is<br />

detectable as an irritant by the human nervous system at levels as low as 5 ppm. Yet, the human<br />

body is not able to recognize and identify the irritant odor as ammonia (an act involving sensory<br />

55 Personal communication between GAP legal intern Billie Morelli and sales representative at Pine Environmental<br />

Services, Inc. 1-800-301-9663, 2:30pm, Aug. 1, 2003.<br />

56 An appropriate formula according to one expert consulted by GAP is as follows: {[(# of chemicals monitored / #<br />

of chemicals in tank headspace vapors) * 100] * 0.1 monitoring time while workers are in exposure areas}.<br />

57 IH Deposition, supra note 49, at 54.<br />

58 For example, one IH DRI Survey notes that the IHT employees had reported smelling foul odors to the north and<br />

south of the AP-farm stack exhauster on Sept. 23, 2002. Yet the IHT did not take ammonia and organics<br />

measurements until 9:05 am the next morning, a minimum of nine hours after the odors were detected. All<br />

measurements were 0 ppm, despite that the IHT also smelled a “slight, brief foul odor.” CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID #<br />

02-2198, Sept. 24, 2002.<br />

59 There are numerous examples since January 2002 where vapors have been released in bursts: CHG, IH DRI<br />

Survey at Tank A-101, Feb. 13, 2002 (“Intermittent ammonia odors present downwind. Non-detectable”); CHG, IH<br />

DRI Survey at AY/AZ Farms, Mar. 28, 2002 (“Intermittent NH3 odors present at and around immediate area of<br />

breather filters”); CHG, IH DRI Survey at Tank AP-102, Sept. 18, 2002 (“Intermittent ammonia odor detected<br />

downwind of stack. NH3

glands tied to memory banks in the brain) until concentrations reach at least 50 ppm. 60 In 70<br />

milliseconds, humans can detect and recognize a 50 ppm or higher dose of ammonia. Yet, even if the<br />

monitoring equipment could measure contaminant levels at a two second time weighted average –<br />

this is orders of magnitude less sensitive than the human body‟s detection capabilities.<br />

Unfortunately, it only takes one quick burst of ammonia (or any other contaminant) at the higher<br />

concentrations for biological damage to occur. 61<br />

2. Inadequate Monitoring Procedures and Compliance<br />

In addition to characterization, equipment, and time limitations, CHG‟s monitoring procedures and<br />

methods are also inadequate and confusing.<br />

First, the HASP states that in conducting the Job Hazard Analysis (JHA), if ammonia and organics<br />

levels are exceeded at the source, then the breathing area should be monitored. 62 Yet there are<br />

numerous sources from which vapors could be venting (tank exhausters, pump pits, riggers, electrical<br />

cabinets, drill strings, glove bags, tank covers, nearby tanks), and IHTs are not required to monitor all<br />

sources. Many of the vapors are invisible and odorless, sometimes making it next to impossible to<br />

tell the source of a contaminant about which a worker is complaining. When an IHT misses an active<br />

vapor release point during source monitoring, the contaminants in the worker‟s breathing zone go<br />

unmonitored and undetected. GAP has even found documented instances where IHTs have<br />

responded to odor complaints (which are by nature in the breathing zone), and declined to monitor in<br />

the breathing zone upon finding source readings within permissible exposure limits. 63<br />

Although the HASP indicates that breathing zone monitoring should be performed when ammonia is<br />

detected at a source in excess of 25 ppm, GAP has reviewed other information that suggests that<br />

ammonia (an inorganic) monitoring is required only after non-specific organics have been detected<br />

above 2 ppm. 64<br />

Additionally, there are several instances where the wrong monitoring equipment was used to measure<br />

workers‟ breathing zone. One senior IHT recently pointed out that in reviewing Direct Reading<br />

Instrument (DRI) monitoring reports, she discovered two situations where IHT‟s had tested for<br />

ammonia in the breathing zone using a colormetric (Draeger) tube rather than the Manning EC-P2<br />

ammonia detector that should be used for area measurements. GAP reviewed DRIs obtained through<br />

60 CDC, TOXICOLOGICAL PROFILE FOR AMMONIA, CAS# 7664-41-7, section 1.3, September 2002. available at<br />

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/phs126.html ; John Harte, TOXICS A TO Z: A GUIDE TO EVERYDAY POLLUTION<br />

HAZARDS, supra note 29, at 216; Conversation with retired PNNL toxicologist Timothy Jarvis, PhD.<br />

61 Conversation with retired PNNL toxicologist Timothy Jarvis, PhD.<br />

62 Id.<br />

63 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0118, April 2, 2002 (This survey was in response to an odor complaint. Source<br />

readings were detectable, but not above HASP limits. No breathing zone surveys were conducted in spite of the<br />

workers‟ complaint of odors).<br />

64 In reviewing CHG‟s Industrial Hygiene Direct Reading Instrument Surveys [hereinafter IH DRI Survey], GAP<br />

has found references to a “Monitoring plan 7B100-MAA-02-022” that apparently instructs the IHT to monitor for<br />

ammonia only after non-specific organics have been detected above 2 ppm. For example, DRI Survey from May 2,<br />

2002 notes: “Area monitoring for ammonia was not performed due to no TOC readings above 2 ppm encountered, in<br />

accordance with monitoring plan 7B100-NAA-02-022.” Several DRIs throughout 2002 mention this plan and/or<br />

follow this procedure (i.e., no ammonia monitoring performed when TOC levels were below 2ppm). GAP has not<br />

yet seen a copy of this monitoring plan; CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 03-0225, Jan. 14, 2003 (IHT notes a slight<br />

ammonia smell during maintenance activity, yet only monitoring was for TOCs).<br />

16

FOIA for the months of January through June 2003,<br />

and found a total of 19 instances where Draeger<br />

tubes, rather than the Manning EC, were used to<br />

measure ammonia concentrations in workers‟<br />

breathing zones. 65 In all but two cases, the ammonia<br />

concentrations read non-detectible.<br />

There have been other instances where workers have<br />

entered potentially dangerous situations, such as to<br />

investigate an unexpected exhauster shut-down in<br />

SY farm, without anyone present to conduct any<br />

monitoring for chemical contaminants. 66<br />

An added factor in inaccurate chemical vapor<br />

measurements is the location of the IHT to the source being monitored or the worker complaining of<br />

odors. GAP has received reports from workers that IHTs have taken “source” readings up to a foot<br />

away from the source and area readings several feet away from where the work is being performed.<br />

Such practices increase the likelihood that the IHT will not detect whatever constituents the worker<br />

may smell. Workers have described the situation as similar to sitting around a campfire, where one<br />

person may be inundated by campfire smoke and yet a second person only two feet away may not<br />

notice anything.<br />

Finally, the monitoring procedures CHG has put in place cannot protect workers when those<br />

procedures are not followed, the equipment does not work properly, or decision-makers are<br />

unavailable during possible emergencies:<br />

On March 22, 2002, a heavy smoke odor was present at the work area. 67 The IHT did not<br />

call this in for over an hour.<br />

On April 1, 2002, an odor was present and high levels of organics were detected in the<br />

workers‟ breathing zone. The IHT did not check for ammonia. Instead he wrote a note on<br />

the survey that said, “closed doors to mitigate odors.” 68<br />

On April 8, 2002, the monitor was not working properly, yet the IHT continued using that<br />

instrument. 69<br />

On May 8, 2002, organics levels inside a tent were 27 ppm (respirators are required at 2<br />

ppm). The IHT‟s note does not mention respirators (supplied air is required where organics<br />

are above 25 ppm), but does comment that “operator cut windows into Petro tent to exhaust<br />

out fumes.” 70<br />

65 CHG, IH DRI Survey ID # [hereinafter DRI #] 03-0062 (Jan. 16, 2003); DRI # 03-0113 (Jan. 27, 2003); DRI #<br />

03-1004 (Jan. 27, 2003); DRI # 03-0421 (Jan. 30, 2003); DRI # 03-0132 (Jan. 30, 2003); DRI # 03-0187 (Feb. 10,<br />

2003); DRI # 03-0192 (Feb. 11, 2003); DRI # 03- 0193 (Feb. 11, 2003); DRI # 03-0199 (Feb. 12, 2003); DRI # 03-<br />

0638 (Feb. 19, 2003); DRI # 03-772 (Mar. 12, 2003); DRI # 03-726 (Mar. 17, 2003); DRI # 03-0776 (Mar. 28,<br />

2003); DRI # 03-0786 (Mar. 30, 2003); DRI # 03-01467 (Apr. 5, 2003); DRI # 03-1529 (Apr. 28, 2003); DRI # 03-<br />

1535 (Apr. 29, 2003); DRI # 03-1548 (May 2, 2003); DRI # 03-1565 (May 7, 2003).<br />

66 PER-2003-1121, Mar. 18, 2003.<br />

67 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0078, Mar. 22, 2002<br />

68 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-1468, April 1, 2002<br />

69 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0768, April 8, 2002<br />

70 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0235, May 8, 2002<br />

17

On June 14, 2002, headspace organics levels were consistently saturating the monitoring<br />

instrument, reading 9,999 ppm. When the IHT called in to report this, no one answered and<br />

he had to leave a message. When his call was returned, he was directed to proceed with<br />

monitoring, and call back if high levels were received again. A nearby health physics<br />

technician complained of a creosote odor. It wasn‟t until an hour later, when a pressurization<br />

alarm went off, that all personnel evacuated the farm. 71<br />

On November 19, 2002, workers were wearing HEPA respirators in the presence of high<br />

levels of organics. HEPA respirators do not filter organic vapors. 72<br />

In April 2003, the boundary demarcating the Air Monitoring Zone (AMZ) around an<br />

exhauster was reconfigured without the permission of the responsible IH person.<br />

Additionally, a vapor warning sign posted on the Constant Air Monitor (CAM) cabinet inside<br />

the AMZ was removed without the permission of the responsible IH person. 73<br />

3. A Case Study in Monitoring Failure<br />

The limitations of CHG‟s monitoring policies and practices are clearly demonstrated by the fact that<br />

there are several recorded instances that even while the person conducting the monitoring is smelling<br />

odors, the monitoring equipment indicates that contaminant levels are non-detectible. 74 CHG asserts<br />

that this is because workers can smell ammonia at levels that are lower than the equipment<br />

monitoring equipment can detect. Yet, as explained above, ammonia can not be detected until it<br />

reaches concentrations of 5 ppm and cannot be recognized as ammonia until it reaches a<br />

concentration of around 50 ppm. There are several potential explanations for the failure in CHG‟s<br />

ability to detect the contaminants that workers are experiencing:<br />

Workers are smelling something other than ammonia, to which the monitoring equipment is<br />

not calibrated or is incapable of detecting.<br />

The vapors are coming out of the source in intermittent bursts too inconsistent and quick for<br />

the monitoring equipment to register.<br />

Monitoring is not being conducted at the right place – too far from the workers, not at the<br />

source, or not in the vapor plume.<br />

71 CHG, IH DRI Survey,, ID # 02-0313, June 14, 2002<br />

72 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-2284, Nov. 19, 2002<br />

73 PER-2003-1591, Apr. 22, 2003.<br />

74 CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0024, Jan. 26, 2002 (“Called out to investigate high odor report by power operator<br />

. . . slight odor was apparent . . . readings remained 0 ppm in field.”); CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID #02-0716, Jan. 29,<br />

2002 (“Although no detectable readings were obtained, an odor was detected by the NPO, PO, IH, and IHT.”);<br />

CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0107, April 1, 2002 (“Operator asked about organics as he said he smelled a stinky<br />

egg odor in hole when putting monitoring tube down into pit. I told him no organics were detected.”); CHG, IH<br />

DRI Survey, ID # 02-0325, June 19, 2002 (“A mild ammonia odor was detected around breather filter however it<br />

was below the detection level of the instrument.”); CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-0341, July 2, 2002 (“Checked<br />

around areas where workers were and nothing detected on ammonia instrument, however there was a mild to<br />

moderate ammonia odor detected by me.”); CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-2139, Aug. 30, 2002 (“All readings were<br />

0 ppm. A very slight brief pungent smell occurred downwind of stack.”); CHG, IH DRI Survey, ID # 02-2198, Nov.<br />

9 2002 (“A slight brief foul odor was smelled approx. 50‟ downwind of stack and no readings were detected.”);<br />

CHG, IH DRI Survey ID # 03-0246, Jan. 22, 2003 (“When doing this job you could smell a faint odor but nothing<br />

detectable on any of the instruments.”); CHG, IH DRI Survey ID # 03-0187, Feb. 10, 2003 (“Mild ammonia odor<br />

detected around AN exhauster area, but instrument showed

The wrong kind of monitoring equipment is being used.<br />

C. Personal Protective Equipment – CHG Procedures and Practices<br />

CHG safety procedures restrict tank farm employees from working in an area without approved<br />

respiratory protection where contaminant levels in the breathing zone may exceed 2 ppm (for three<br />

minutes) for volatile organic compounds (VOC) and/or 25 ppm for ammonia. When the Job Hazard<br />

Analysis (JHA) indicates that employees may be entering an area in excess of these levels, workers<br />

are supposed to be required to use a full face respirator with cartridges, usually the GME-P100.<br />

Additionally, CHG asserts that employees may receive a nuisance mask or a full face respirator at<br />

any time, upon request. 75 The HASP requires workers to wear supplied air respirators when a<br />

potentially hazardous atmosphere exists and any of the following occur:<br />

conditions are unknown or uncharacterized 76<br />

contaminants have poor warning properties 77<br />

contaminant concentrations exceed the respirator canister limits 78<br />

contaminant concentrations are at levels that are considered to be immediately dangerous to<br />

life and health (IDLH). 79 There are three general categories of<br />

respirators used by CHG at <strong>Hanford</strong>‟s tank<br />

farms. There are dust or nuisance masks; full<br />

face respirators with cartridge filters (CHG<br />

primarily uses the Mine Safety Appliance<br />

GME-P100 Combination Cartridge); and<br />

supplied air (self contained breathing<br />

apparatus (SCBA) or air line respirators).<br />

Despite the sharp increase in recent vapor<br />

exposures, CHG rarely requires workers to<br />

wear basic respiratory protection (much less<br />

supplied air respirators) when going out on a<br />

job. Furthermore, when respirators are<br />

required, they are often insufficient or ineffective. A recent Problem Evaluation Request filed by a<br />

tank farm worker cogently explains the problem:<br />

During the course of my duties as an HPT [Health Physics Technician] . . . I was<br />

asked to respond to an “event” at the 241-C tank farm. An operator had complained<br />

of headache and nausea after being exposed to unknown tank vapors and was<br />

subsequently transported to KADLEC medical center for evaluation. At this time, C-<br />

farm was evacuated. My task was to accompany an operator and an IH technician<br />

into C Farm. I was to evaluate the radiological conditions while the IHT checked for<br />