National Medical Policy - Health Net

National Medical Policy - Health Net

National Medical Policy - Health Net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

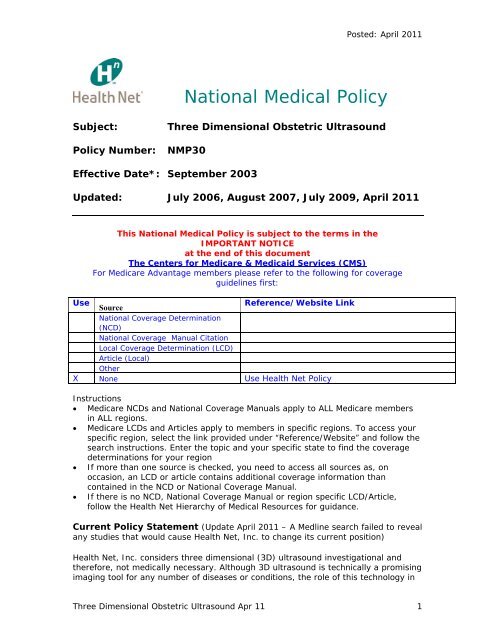

Posted: April 2011<br />

<strong>National</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Policy</strong><br />

Subject:<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Number:<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound<br />

NMP30<br />

Effective Date*: September 2003<br />

Updated: July 2006, August 2007, July 2009, April 2011<br />

This <strong>National</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> is subject to the terms in the<br />

IMPORTANT NOTICE<br />

at the end of this document<br />

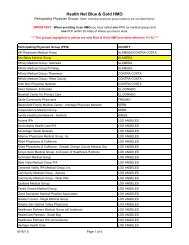

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)<br />

For Medicare Advantage members please refer to the following for coverage<br />

guidelines first:<br />

Use<br />

Source<br />

Reference/Website Link<br />

<strong>National</strong> Coverage Determination<br />

(NCD)<br />

<strong>National</strong> Coverage Manual Citation<br />

Local Coverage Determination (LCD)<br />

Article (Local)<br />

Other<br />

X None Use <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> <strong>Policy</strong><br />

Instructions<br />

• Medicare NCDs and <strong>National</strong> Coverage Manuals apply to ALL Medicare members<br />

in ALL regions.<br />

• Medicare LCDs and Articles apply to members in specific regions. To access your<br />

specific region, select the link provided under “Reference/Website” and follow the<br />

search instructions. Enter the topic and your specific state to find the coverage<br />

determinations for your region<br />

• If more than one source is checked, you need to access all sources as, on<br />

occasion, an LCD or article contains additional coverage information than<br />

contained in the NCD or <strong>National</strong> Coverage Manual.<br />

• If there is no NCD, <strong>National</strong> Coverage Manual or region specific LCD/Article,<br />

follow the <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> Hierarchy of <strong>Medical</strong> Resources for guidance.<br />

Current <strong>Policy</strong> Statement (Update April 2011 – A Medline search failed to reveal<br />

any studies that would cause <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>, Inc. to change its current position)<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>, Inc. considers three dimensional (3D) ultrasound investigational and<br />

therefore, not medically necessary. Although 3D ultrasound is technically a promising<br />

imaging tool for any number of diseases or conditions, the role of this technology in<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 1

Posted: April 2011<br />

reaching the correct diagnosis has not been clearly translated into clinical<br />

improvement of patient outcome.<br />

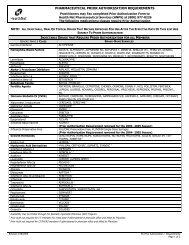

Codes Related To This <strong>Policy</strong><br />

ICD-9 Codes<br />

V22.0-V22.2 Normal pregnancy<br />

V23.0-V23.9 Supervision of high-risk pregnancy<br />

CPT Codes<br />

76375<br />

Coronal sagittal, multiplanar, oblique, 3-Dimensional and/or<br />

holographic reconstruction of computerized tomography,<br />

magnetic resonance imaging, or other topographic modality<br />

(may be considered medically unnecessary and denied if<br />

equivalent information to that obtained from the test has<br />

already been provided by another procedure (magnetic<br />

resonance imaging, ultrasound, angiography, etc.), or could be<br />

provided by a standard CT Scan (2-Dimensional) without<br />

reconstruction (deleted 12/31/05)<br />

76376 3D rendering with interpretation and reporting of computed<br />

tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, or other<br />

tomographic modality; not requiring image post processing on<br />

an independent workstation<br />

76377 3D rendering with interpretation and reporting of computed<br />

tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, or other<br />

tomographic modality; requiring image post processing on an<br />

independent workstation<br />

HCPCS Codes<br />

N/A<br />

Scientific Rationale – Update July 2009<br />

Ultrasonography in pregnancy should be performed only when there is a valid<br />

medical indication. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)<br />

[2009] stated, "The use of either two-dimensional or three-dimensional<br />

ultrasonography only to view the fetus, obtain a picture of the fetus, or determine<br />

the fetal sex without a medical indication is inappropriate and contrary to responsible<br />

medical practice."<br />

Current guidelines on ultrasonography in pregnancy from the American College of<br />

Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2009) state: "The technical advantages of 3-<br />

dimensional ultrasonography include its ability to acquire and manipulate an infinite<br />

number of planes and to display ultrasound planes traditionally inaccessible by 2-<br />

dimensional ultrasonography. Despite these technical advantages, proof of a clinical<br />

advantage of 3-dimensional ultrasonography in prenatal diagnosis in general is still<br />

lacking. Potential areas of promise include fetal facial anomalies, neural tube<br />

defects, and skeletal malformations where 3-dimensional ultrasonography may be<br />

helpful in diagnosis as an adjunct to, but not a replacement for, 2-dimensional<br />

ultrasonography. Until clinical evidence shows a clear advantage to conventional 2-<br />

dimensional ultrasonography, 3-dimensional ultrasonography is not considered a<br />

required modality at this time."<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 2

Posted: April 2011<br />

Scientific Rationale – Update August 2007<br />

According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) practice<br />

bulletin, Ultrasonography in Pregnancy, “Proof of a clear advantage of 3-dimensional<br />

ultrasonography in prenatal diagnosis is not present when compared with 2-<br />

dimensional imaging by an experienced clinician. Therefore, 3-dimensional imaging is<br />

not considered a required modality at this time.”<br />

Wang et al. (2007) investigated the prenatal diagnostic accuracy of two-dimensional<br />

ultrasound (2DUS) alone versus 2DUS in conjunction with three-dimensional<br />

ultrasonography (3DUS) including orthogonal display (OGD) and three-dimensional<br />

extended imaging for cleft lip and primary palate. Fetuses being suspected of having<br />

a facial cleft by previous ultrasound examination or family history were examined<br />

sequentially with 2DUS and then 3DUS. Of a total of 30 infants, 22 had cleft lip and<br />

nine also had cleft palate at birth. The use of 2DUS with or without 3DUS correctly<br />

identified all cases of cleft lips prenatally. However, the use of 2DUS in conjunction<br />

with 3DUS correctly identified more cleft primary palate than 2DUS alone (88.9% vs<br />

22.2%). Cleft primary palate was well demonstrated in both the multi-slice view<br />

(MSV) and OGD modes. In one case, a cleft palate was shown in the MSV mode but<br />

not in the Oblique view(OBV) mode. All the unaffected fetuses were reported as no<br />

cleft palate with the use of MSV mode. The investigator concluded the combined<br />

approach of 2DUS and 3DUS with both OGD and MSV modes significantly improved<br />

the prenatal detection rate for a cleft palate compared with 2DUS alone (88.9% vs<br />

22.2%) without decreasing the specificity.<br />

Goncalves et al. (2005) performed a review of the published literature on 3-<br />

dimensional ultrasound (3DUS) and 4-dimensional ultrasound (4DUS) in obstetrics to<br />

determine whether 3DUS adds diagnostic information to what is currently provided<br />

by 2-dimensional ultrasound (2DUS) and, if so, in what areas. A PubMed search<br />

found 525 articles reporting on the use of 3DUS or 4DUS in obstetrics related to the<br />

subject of the review. Articles describing technical developments, clinical studies,<br />

reviews, editorials, and studies on fetal behavior or maternal-fetal bonding were<br />

reviewed. The reviewers found that three-dimensional ultrasound provides<br />

additional diagnostic information for the diagnosis of facial anomalies, especially<br />

facial clefts. They also found evidence that 3DUS provides additional diagnostic<br />

information in neural tube defects and skeletal malformations. Large studies<br />

comparing 2DUS and 3DUS for the diagnosis of congenital anomalies have not<br />

provided conclusive results. They noted preliminary evidence suggests that<br />

sonographic tomography may decrease the examination time of the obstetric<br />

ultrasound examination, with minimal impact on the visualization rates of anatomic<br />

structures. The reviewers concluded three-dimensional ultrasound provides<br />

additional diagnostic information for the diagnosis of facial anomalies, evaluation of<br />

neural tube defects, and skeletal malformations. Additional research is needed to<br />

determine the clinical role of 3DUS and 4DUS for the diagnosis of congenital heart<br />

disease and central nervous system anomalies. Future studies should determine<br />

whether the information contained in the volume data set, by itself, is sufficient to<br />

evaluate fetal biometric measurements and diagnose congenital anomalies.<br />

In a prospective randomized pilot study among low risk women with singleton<br />

fetuses in the second and third trimester, Lapaire et al. (2007) assessed the impact<br />

of three-dimensional (3D) versus two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound (US) on<br />

maternal-fetal bonding. Sixty women were randomized to either 2D US or 3D US<br />

and the effects were recorded with standardized questionnaires. Although the<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 3

Posted: April 2011<br />

quality of 2D US, assessed by the examinator, was superior to 3D US, maternal<br />

recognition was higher with 3-D US. With 2D US, nulliparous patients had<br />

significantly more difficulties visualizing the fetus, than multiparous. However, the<br />

maternal preference of 3D US had no significant impact on maternal-fetal bonding.<br />

The investigator concluded ultrasound had no significant effect on maternal-fetal<br />

bonding. Three-dimensional images may facilitate recognition of the fetus, but 3D US<br />

did not have higher impact on maternal-fetal bonding. This finding may be a reason<br />

not to consider 3D ultrasound for routine scanning<br />

According to the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, “Currently, twodimensional<br />

(2D) gray-scale real-time sonography is the primary method of<br />

medically indicated anatomic imaging with ultrasound. The term three-dimensional<br />

(3D) ultrasound refers to the acquisition of imaging data from a volume of tissue.<br />

This volumetric data can be displayed as slabs of varying thickness, multiplanar<br />

reconstruction or as a rendered image. The 2D display remains the primary method<br />

of image presentation regardless of the method of acquisition. While 3D ultrasound<br />

may be helpful in diagnosis, it is currently an adjunct to, but not a replacement for<br />

2D ultrasound. As with any developing technology, its clinical value may improve and<br />

its diagnostic role will be periodically re-evaluated”<br />

Scientific Rationale<br />

Two-dimensional (2D) sonography is the traditional way we have been using<br />

ultrasound in all areas of medicine to display normal and abnormal anatomy. More<br />

recently, three dimensional (3D) ultrasound has emerged as the novel sonographic<br />

method that can enhance diagnostic capability over standard 2D ultrasound. Even<br />

though this ability to display a 3D image may become one of the most powerful<br />

recent advances in sonography, critics of the technique feel that three-dimensional<br />

ultrasound has been over rated and that the training afforded to 2D sonographers<br />

enables them to perform 3D reconstructions in their mind’s eye, with similar results<br />

as those described with actual 3D displays.<br />

Numerous studies conducted on the use of 3D ultrasound demonstrate that this noninvasive<br />

method is technically feasible and suggest potential benefits for some of the<br />

proposed indications. However, there is a paucity of high quality direct evidence<br />

demonstrating the impact on diagnostic thinking and therapeutic decision-making. In<br />

addition, the techniques of acquiring the capabilities to perform 3D ultrasound,<br />

appropriate patient selection criteria, and interpreting the results are not well<br />

standardized. There is no adequate evidence that 3D ultrasound can prevent or<br />

retard the development and/or progression of the long-term complications of any<br />

diseases or conditions; nor is there evidence that 3D ultrasound can prolong the life<br />

of patients. Prospective clinical studies are needed to determine the clinical value of<br />

3D ultrasound over standard 2D ultrasound in the assessment of patients. The<br />

following enumerates the potential uses of 3D ultrasound.<br />

2D ultrasound is used routinely in obstetrics and gynecology. Today, nearly all<br />

pregnant women undergo at least one ultrasound during her pregnancy. These<br />

ultrasounds are designed to assess fetal well-being and gestational age. The<br />

traditional 2D ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to bounce off the<br />

surfaces and structures of the fetus producing echos, which can be assessed on the<br />

video screen. Although clinicians are generally adept at using this information, the<br />

image remains distorted and vague to say the least. In the last couple of years, the<br />

creation of 3D ultrasound for use in obstetrics has come to fruition. 3D ultrasound is<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 4

Posted: April 2011<br />

done the same way as the traditional ultrasound with the addition of software to<br />

enhance the image and produce a three dimensional image.<br />

A further benefit of 3D ultrasonography is that it can provide caregivers in primary<br />

facilities with less experience and expertise in ultrasonography an opportunity for<br />

remote referrals and consultations for complicated cases. 3D images can be digitally<br />

stored with the complete data set conveyed by an Internet connection from the<br />

primary caregiver to experts across the world. This allows the consultant to have an<br />

entirety of imaging information required to make a diagnosis. Furthermore, the online<br />

transmission enables feedback and interaction with a specialist at the time of or<br />

immediately after an ultrasonographic examination, thus limiting the need for further<br />

referrals. Telemedicine has only begun to demonstrate itself as a useful tool and 3D<br />

ultrasonography is ideally suited to promote this upcoming aspect of care in<br />

medicine. Imaging physicians already use 3D volume imaging techniques in CT and<br />

MR and are likely to become comfortable working in a volume or multiplanar<br />

environment in ultrasound as well.<br />

One of the most consistently used justifications for the use of obstetric<br />

ultrasonography is that accurate diagnosis of fetal malformations before delivery can<br />

provide both health care providers and parents a number of management options<br />

that before the advent of this technique were unavailable. However, reports from the<br />

Routine Antenatal Diagnostic Imaging with Ultrasound (RADIUS) trial have<br />

challenged this particular tenet. These researchers indicated that screening with<br />

ultrasonography did not significantly influence the management or outcome of<br />

pregnancies complicated by congenital malformations. Its role in gynecology has not<br />

been clearly established. It may be indicated only when equivalent information<br />

resulting in clinical improvement in fetal and maternal outcome cannot be obtained<br />

by another standard test (2D ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, CT Scan,<br />

angiography, etc.). 3D ultrasound may be useful in differentiating between a septate<br />

and a bicornuate uterus or to determine the exact location of a malpositioned<br />

intrauterine device (IUD).<br />

The fetal brain is one of the areas where 3D ultrasound has been most helpful.<br />

Surface rendering of the skull is instrumental in evaluating the status of cranial<br />

sutures and determining whether or not an abnormal head shape is secondary to<br />

craniosynostosis. Three-dimensional surface rendering is also particularly helpful in<br />

the evaluation of other surfaces of the fetal head and face, such as the fetal ears,<br />

which are not normally focused upon using standard 2D cross sectional imaging.<br />

Surface imaging of the fetal face using 3D sonography has probably been the most<br />

notable area of study, not only in the ultrasound literature but also in the lay press<br />

where patients have been able to see the face of their unborn baby more clearly than<br />

ever before. Everyone agrees that 3D sonography of the face is not a screening<br />

technique but an adjunct to a good 2D scan. To date, it is not yet possible to detect<br />

dysmorphologic features using 3D surface rendering although it is hoped that as the<br />

techniques improve, the dysmorphologic fetal facies will be detectable. It is the<br />

evaluation of the fetal cleft lip and palate that has gotten the most attention in the<br />

literature.<br />

Three-dimensional imaging of the normal and abnormal extremities has been studied<br />

extensively using both multi-planar reconstruction and surface rendering. Several<br />

studies have described fetal skeletal dysphasia’s viewed with 3D ultrasound, where<br />

practitioners found that 3D provided additional information on affected fetuses as<br />

compared to 2D. On the other hand, other investigators have not been as<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 5

Posted: April 2011<br />

enthusiastic about the role of 3D for fetuses with these malformations, thus requiring<br />

further investigation to come to a consensus. Opinions that 3D provides diagnostic<br />

details not available using two-dimensional ultrasound remains somewhat anecdotal<br />

and restricted to small case series. It is clear from several reports that although 3D<br />

made additional diagnostic information possible, the technique was not necessary for<br />

definitive diagnosis of spina bifida. 3D ultrasounds, however, did display the level of<br />

the defect more accurately than with conventional scanning. Scoliosis resulting from<br />

vertebral body anomalies was also recognized more easily on a single 3D rendered<br />

image whereas multiple standard 2D images were needed to make the same<br />

diagnosis.<br />

Evaluation of the fetal heart is an intense area of research, however, evaluation of<br />

the heart in 3D can be tricky and requires Doppler gated capabilities. There is still<br />

much work to be done to bring 3D imaging of the heart up to a standard currently<br />

possible using 2D operated by trained personnel. Other areas of investigation include<br />

fetal genital scanning where the fetal perineum can be visualized, although to date,<br />

the performance of 3D technology is reportedly not as good in evaluating fetal<br />

genitals than is 2D imaging alone. By far, the most important function of first<br />

trimester 3D scanning may become the evaluation of the nuchal translucency<br />

measurement of fetuses 11-14 weeks.<br />

Another important clinical application of 3D is volume measurements calculations<br />

based on 3D volume acquisition. Current literature has demonstrated the accuracy of<br />

volume based 3D ultrasonography measurement on follicle aspiration performed<br />

using transvaginal needle guided technique. Other practitioners have also shown that<br />

3D sonographic methods provide accurate measurements of serial fetal lung volume<br />

measurements for the prenatal detection of pulmonary hypoplasia, the fetal thoracolumbar<br />

spine as well as kidneys, brain, liver and heart. Additionally, at the current<br />

time fetal cardiac malformations, which remain the least identifiable of major<br />

malformations, have thus far had only limited benefit from this 3D technique<br />

because of motion artifact. Hypothetically, if the 3D examination demonstrates an<br />

abnormality not seen with 2D imaging, then clinical management of patients may be<br />

altered.<br />

Craniofacial abnormalities that have been identified with 3D ultrasound include cleft<br />

lip or palate, micrognathia, midface hypoplasia, facial dysmorphia, intracranial<br />

abnormalities, hypotelorism, holoprosencephaly and skull defects in the second- and<br />

third-trimester. In expert hands, a 2D ultrasound is sufficient and 3D ultrasound<br />

does not add any valuable diagnostic information. Three-dimensional ultrasound may<br />

facilitate the understanding of the lesion by the parents and facilitate communication<br />

with the plastic surgeons. However, these potential benefits need to be carefully<br />

weighed against the costs of the ultrasound instrumentation, increased examination<br />

time and training of personnel.<br />

Computer technology and software advanced sufficiently in the past five years to<br />

allow real-time reconstruction of 3D images and their visualization and manipulation<br />

on inexpensive desktop computers. Nevertheless, ultrasound imaging still suffers<br />

from several disadvantages related to its 2 dimensional nature, which 3D imaging<br />

attempts to address. Despite decades of exploration, it is only in the past five years<br />

that 3D imaging in ultrasound moved out of the research laboratory to become a<br />

commercial product for routine clinical use.<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 6

Posted: April 2011<br />

A major advantage of 2D ultrasound is its flexibility, allowing the sonologist to<br />

manipulate the transducer and view the desired anatomical section. Paradoxically,<br />

this advantage is one of its weaknesses that 3D imaging attempts to address. Using<br />

conventional ultrasonography, only one thin slice of the patient can be viewed at any<br />

time, and the location of this image plane is controlled by physically manipulating the<br />

transducer orientation. It is difficult to place the 2D image plane at a particular<br />

location within an organ, and even more difficult to find the same location again<br />

later. Thus, 2D US is not optimal for planning or monitoring therapeutic procedures,<br />

or for performing quantitative prospective or follow-up studies.<br />

Consequently, the diagnostician or physician must mentally integrate many 2D<br />

images to form an impression of the 3D anatomy and pathology. This process is<br />

time-consuming and inefficient, but more important, variable and subjective.<br />

Most 3D ultrasound systems have used conventional ultrasound machines with 1D<br />

arrays to collect multiple 2D images and reconstruct them into 3D images. Two<br />

important criteria must be met to avoid inaccuracies or distortions: (1) the relative<br />

position and angulation of the acquired 2D images must be accurately known so that<br />

the reconstructed 3D image is not distorted; and (2)<br />

the image acquisition must be carried out rapidly and/or gated to avoid artifacts<br />

caused by respiratory, cardiac and involuntary motion.<br />

Although 3D ultrasound is a promising tool to image many anatomical sites in the<br />

fetus and the adult female, its clinical benefits are still being researched. There is no<br />

question that the pictures far exceed the surface detail of the traditional grainy,<br />

black-and-white, 2D ultrasound images. However, at the present time 3D ultrasound<br />

is rarely critical in reaching the correct diagnosis and it may take a few more years<br />

before the place of 3D ultrasound as a diagnostic tool can be defined more precisely.<br />

There are scant outcome studies and much research is needed as the 3D technology<br />

is further developed.<br />

Review History<br />

September 9, 2003<br />

July 2006<br />

August 2007<br />

July 2009<br />

April 2011<br />

<strong>Medical</strong> Advisory Council<br />

Update – no revisions<br />

Update – no revisions<br />

Update. No Revisions. Codes reviewed.<br />

Update. Added Medicare Table. No revisions.<br />

Patient Education Websites<br />

English<br />

1. American College of Radiology, Radiological Society of North America.<br />

Ultrasound: Obstetric. Available at:<br />

http://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?PG=obstetricus<br />

Spanish<br />

1. American College of Radiology, Radiological Society of North America.<br />

Ultrasonido obstétrico. Acesso en:<br />

http://www.radiologyinfo.org/sp/info.cfm?pg=obstetricus<br />

This policy is based on the following evidence-based guidelines:<br />

1. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. (ACOG) Practice Bulletin<br />

Number 58. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologist.<br />

Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. December 2004<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 7

Posted: April 2011<br />

2. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 3D Technology. Nov 2005.<br />

Available at:<br />

http://www.aium.org/publications/statements/_statementSelected.asp?stateme<br />

nt=23<br />

3. Hayes <strong>Medical</strong> Technology Directory. Three-Dimensional and Four-Dimensional<br />

Ultrasound for Extrafetal and Maternal Structures in Pregnancy. July 2006<br />

4. Hayes <strong>Medical</strong> Technology Directory. Three-Dimensional and Four-Dimensional<br />

Ultrasound for Diagnosis of Fetal Head Abnormalities. Nov 2005<br />

5. Hayes <strong>Medical</strong> Technology Directory Three-Dimensional and Four-Dimensional<br />

Ultrasound for High-Risk Pregnancies and Routine Screening. Nov 2005<br />

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Committee on<br />

Practice Bulletins. Obstetrics. Ultrasonography in pregnancy. ACOG Practice<br />

Bulletin No. 101. Washington, DC: ACOG; February 2009.<br />

References – Update April 2011<br />

1. Yagel S, Cohen SM, Messing B, Valsky DV. Three-dimensional and fourdimensional<br />

ultrasound applications in fetal medicine. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol.<br />

2009;21(2):167-174.<br />

2. Chen M, Wang HF, Leung TY, et al. First trimester measurements of nasal bone<br />

length using three-dimensional ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(8):766-770.<br />

References – Update July 2009<br />

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Committee on<br />

Practice Bulletins. Obstetrics. Ultrasonography in pregnancy. ACOG Practice<br />

Bulletin No. 98. Washington, DC: ACOG; October 2008.<br />

2. Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee; Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee,<br />

Delaney M, Roggensack A, Leduc DC, et al. Guidelines for the management of<br />

pregnancy at 41+0 to 42+0 weeks. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(9):800-<br />

823.<br />

3. Chen M, Lee CP, Lam YH, et al. Comparison of nuchal and detailed morphology<br />

ultrasound examinations in early pregnancy for fetal structural abnormality<br />

screening: A randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol.<br />

2008;31(2):136-146; discussion 146.<br />

References – Update August 2007<br />

1. Wang LM, Leung KY, Tang M. Prenatal evaluation of facial clefts by threedimensional<br />

extended imaging. Prenat Diagn. 2007 May 29;<br />

2. Lapaire O, Alder J, Peukert R, Holzgreve W, Tercanli S. Two- versus threedimensional<br />

ultrasound in the second and third trimester of pregnancy: impact<br />

on recognition and maternal-fetal bonding. A prospective pilot study. Arch<br />

Gynecol Obstet. 2007 Apr 25.<br />

3. Goncalves LF, Lee W, Espinoza J, Romero R. Three- and 4-dimensional<br />

ultrasound in obstetric practice: does it help? J Ultrasound Med. 2005<br />

Dec;24(12):1599-624.<br />

4. Towner D, Boe N, Lou K, Gilbert WM. Cervical length measurements in<br />

pregnancy are longer when measured with three-dimensional transvaginal<br />

ultrasound. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004 Sep;16(3):167-70.<br />

References<br />

1. Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, et al. Reproducibility of three-dimensional<br />

ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet<br />

Gynecol 2003; 21(6):578-82<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 8

Posted: April 2011<br />

2. Ghi T. Two-dimensional ultrasound is accurate in the diagnosis of fetal<br />

craniofacial malformation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 19(6):543-51<br />

3. Timor-Tritsch IE, Platt LD. Three-dimensional ultrasound experience in<br />

obstetrics. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2002; 14(6):569-75<br />

4. Pooh RK, Pooh K. Transvaginal 3D and Doppler ultrasonography of the fetal<br />

brain. Semin Perinatol 2001; 25(1):38-43<br />

5. Kurjak A, Hafner T, Kos M, et al. Three-dimensional sonography in prenatal<br />

diagnosis: a luxury or a necessity? J Perinat Med 2000; 28(3):194-209<br />

6. Lai TH, Chang CH, Yu CH, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of alobar holoprosencephaly<br />

by two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasound. Prenat Diagn 2000;<br />

20(5):400-3<br />

7. Ayida G, Kennedy S, Barlow D, et al. Contrast sonography for uterine cavity<br />

assessment: A comparison of conventional two-dimensional with threedimensional<br />

transvaginal ultrasound: A pilot study. Fertil Steril 1996; 66:848<br />

8. Baba K, Okai T, Kozuma S, et al: Real-time processable three-dimensional US in<br />

obstetrics. Radiology 1997; 203:571<br />

9. Brandl H, Gritzky A, Haizinger M. Three-dimensional ultrasound: A dedicated<br />

system. Eur Radiol 1999; 9(suppl 3):S331,<br />

10. Brunner M, Obruca A, Bauer P, et al. Clinical application of volume estimation<br />

based on three-dimensional ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1995;<br />

6:358<br />

11. Chang FM, Hsu KF, Ko HC, et al. Fetal heart volume assessment by threedimensional<br />

ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 9:942<br />

12. Chang FM, Hsu KF, Ko HC, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound assessment of<br />

fetal liver volume in normal pregnancy: A comparison of reproducibility with<br />

two-dimensional ultrasound and a search for a volume constant. Ultrasound<br />

Med Biol 1997; 23:381<br />

13. Downey DB, Fenster A. 3-D US: A maturing technology. Ultrasound Quarterly<br />

1998;14:25<br />

14. Feichtinger W. Transvaginal three-dimensional imaging. Fertil Steril 1998;<br />

70:374<br />

15. Thomas R, Pretorius N, Pretorius DH. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging.<br />

UMB 1998; 24, 1243.<br />

16. Gilja OH, Hausken T, Berstad A, et al. Measurements of organ volume by<br />

ultrasonography. Proc Inst Mech Eng 1999; 213:247<br />

17. Johnson DD, Pretorius DH, Budorick NE, et al. Three-dimesnional ultrasound of<br />

the fetal lip and primary palate. Radiology 2000; 217:236<br />

18. Jurkovic D, Geipel A, Gruboeck K, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound for the<br />

assessment of uterine anatomy and detection of congenital anomalies: A<br />

comparison with HSG and two-dimensional sonography. Ultrasound Obstet<br />

Gynecol 1995; 5:233<br />

19. Jurkovic D, Gruboeck K, Tailor A, et al. Ultrasound screening for congenital<br />

uterine anomalies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 199; 104:1320<br />

20. Kupesic S, Kurjak A. Diagnosis and treatment outcome of the septate uterus.<br />

Croat Med J 1998; 39:185,<br />

21. Lee A, Eppel W, Sam C, et al. Intrauterine device localization by threedimensional<br />

transvaginal sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 10:289<br />

22. Lee A, Kratochwil A, Stumpflen I, et al. Fetal lung volume determination by<br />

three-dimensional ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 175:588<br />

23. Merz E. Three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound in gynecological diagnosis.<br />

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 14:81<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 9

Posted: April 2011<br />

24. Merz E, Weber G, Bahlmann F, et al. Application of transvaginal and abdominal<br />

three-dimensional ultrasound for the detection or exclusion of malformations of<br />

the fetal face. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 9:237<br />

25. Nelson TR, Pretorius DH. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound<br />

Med Biol 1998; 24:1243,<br />

26. Platt LD, Santulli T, Carlson DE, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasonography in<br />

obstetrics and gynecology: Preliminary experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;<br />

178:1199<br />

27. Session DR, Daniel SW, Dumesic DA. Three-dimensional ultrasound in<br />

gynecology. Journal of Gynecologic Techniques 1998; 4:125<br />

28. Shih JC, Shyu MK, Lee CN, et al. Antenatal depiction of the fetal ear with threedimensional<br />

ultrasonography. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 91:500<br />

29. Fenster A, Downey DB. 3-D ultrasound imaging: A review. IEEE Engineering in<br />

Medicine and Biology 1996; 15:41-51<br />

30. Fenster A, Tong S, Sherebrin S, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging.<br />

SPIE 1995; 2432:176.<br />

31. Rankin RN, Fenster A, Downey DB, et al. Three-dimensional sonographic<br />

reconstruction: techniques and diagnostic applications. AJR 1993; 161:695-702.<br />

32. Sherebrin S, Fenster A, Rankin R, Spence JD. Freehand three-dimensional<br />

ultrasound: implementation and applications. SPIE Physics of <strong>Medical</strong> Imaging<br />

1996; 2708:296-303.<br />

33. Pretorius DH, Nelson TR. Prenatal visualization of cranial sutures and<br />

fontanelles with three-dimensional ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med 13:871-<br />

876, 1994.<br />

34. Pretorius DH, Nelson TR. Fetal face visualization using three-dimensional<br />

ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med 14:349-356, 1995.<br />

35. Nelson TR, Pretorius DH. Three-dimensional ultrasound of fetal surface features.<br />

Ultras Obstet Gynecol 1992; 2:166.<br />

Important Notice<br />

General Purpose.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>'s <strong>National</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> Policies (the "Policies") are developed to assist <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> in administering<br />

plan benefits and determining whether a particular procedure, drug, service or supply is medically<br />

necessary. The Policies are based upon a review of the available clinical information including clinical<br />

outcome studies in the peer-reviewed published medical literature, regulatory status of the drug or device,<br />

evidence-based guidelines of governmental bodies, and evidence-based guidelines and positions of select<br />

national health professional organizations. Coverage determinations are made on a case-by-case basis<br />

and are subject to all of the terms, conditions, limitations, and exclusions of the member's contract,<br />

including medical necessity requirements. <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> may use the Policies to determine whether under the<br />

facts and circumstances of a particular case, the proposed procedure, drug, service or supply is medically<br />

necessary. The conclusion that a procedure, drug, service or supply is medically necessary does not<br />

constitute coverage. The member's contract defines which procedure, drug, service or supply is covered,<br />

excluded, limited, or subject to dollar caps. The policy provides for clearly written, reasonable and current<br />

criteria that have been approved by <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>’s <strong>National</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> Advisory Council (MAC). The clinical<br />

criteria and medical policies provide guidelines for determining the medical necessity criteria for specific<br />

procedures, equipment, and services. In order to be eligible, all services must be medically necessary and<br />

otherwise defined in the member's benefits contract as described this " Important Notice" disclaimer. In all<br />

cases, final benefit determinations are based on the applicable contract language. To the extent there are<br />

any conflicts between medical policy guidelines and applicable contract language, the contract language<br />

prevails. <strong>Medical</strong> policy is not intended to override the policy that defines the member’s benefits, nor is it<br />

intended to dictate to providers how to practice medicine.<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Effective Date and Defined Terms.<br />

The date of posting is not the effective date of the <strong>Policy</strong>. The <strong>Policy</strong> is effective as of the date determined<br />

by <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>. All policies are subject to applicable legal and regulatory mandates and requirements for<br />

prior notification. If there is a discrepancy between the policy effective date and legal mandates and<br />

regulatory requirements, the requirements of law and regulation shall govern. * In some states, new or<br />

revised policies require prior notice or posting on the website before a policy is deemed effective. For<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 10

Posted: April 2011<br />

information regarding the effective dates of Policies, contact your provider representative. The Policies do<br />

not include definitions. All terms are defined by <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong>. For information regarding the definitions of<br />

terms used in the Policies, contact your provider representative.<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Amendment without Notice.<br />

<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> reserves the right to amend the Policies without notice to providers or Members. In some<br />

states, new or revised policies require prior notice or website posting before an amendment is deemed<br />

effective.<br />

No <strong>Medical</strong> Advice.<br />

The Policies do not constitute medical advice. <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> does not provide or recommend treatment to<br />

members. Members should consult with their treating physician in connection with diagnosis and<br />

treatment decisions.<br />

No Authorization or Guarantee of Coverage.<br />

The Policies do not constitute authorization or guarantee of coverage of particular procedure, drug, service<br />

or supply. Members and providers should refer to the Member contract to determine if exclusions,<br />

limitations, and dollar caps apply to a particular procedure, drug, service or supply.<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Limitation: Member’s Contract Controls Coverage Determinations.<br />

The determination of coverage for a particular procedure, drug, service or supply is not based upon the<br />

Policies, but rather is subject to the facts of the individual clinical case, terms and conditions of the<br />

member’s contract, and requirements of applicable laws and regulations. The contract language contains<br />

specific terms and conditions, including pre-existing conditions, limitations, exclusions, benefit maximums,<br />

eligibility, and other relevant terms and conditions of coverage. In the event the Member’s contract (also<br />

known as the benefit contract, coverage document, or evidence of coverage) conflicts with the Policies,<br />

the Member’s contract shall govern. Coverage decisions are the result of the terms and conditions of the<br />

Member’s benefit contract. The Policies do not replace or amend the Member’s contract. If there is a<br />

discrepancy between the Policies and the Member’s contract, the Member’s contract shall govern.<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Limitation: Legal and Regulatory Mandates and Requirements.<br />

The determinations of coverage for a particular procedure, drug, service or supply is subject to applicable<br />

legal and regulatory mandates and requirements. If there is a discrepancy between the Policies and legal<br />

mandates and regulatory requirements, the requirements of law and regulation shall govern.<br />

<strong>Policy</strong> Limitations: Medicare and Medicaid.<br />

Policies specifically developed to assist <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> in administering Medicare or Medicaid plan benefits and<br />

determining coverage for a particular procedure, drug, service or supply for Medicare or Medicaid<br />

members shall not be construed to apply to any other <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Net</strong> plans and members. The Policies shall<br />

not be interpreted to limit the benefits afforded Medicare and Medicaid members by law and regulation.<br />

Three Dimensional Obstetric Ultrasound Apr 11 11