Orientalizing the Pacific Rim: - History, Department of

Orientalizing the Pacific Rim: - History, Department of

Orientalizing the Pacific Rim: - History, Department of

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

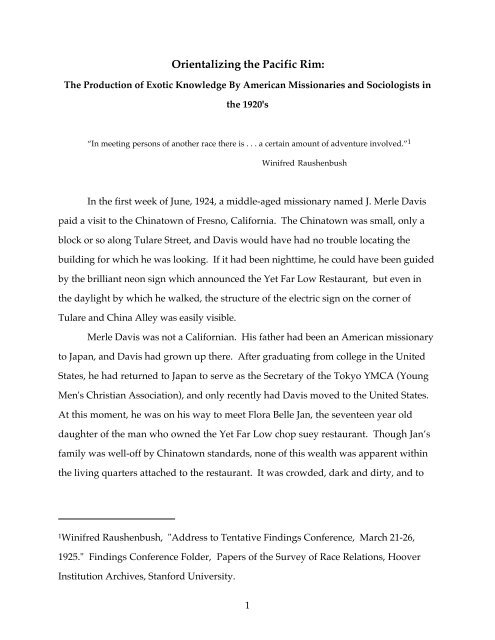

<strong>Orientalizing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Rim</strong>:<br />

The Production <strong>of</strong> Exotic Knowledge By American Missionaries and Sociologists in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1920's<br />

“In meeting persons <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r race <strong>the</strong>re is . . . a certain amount <strong>of</strong> adventure involved.” 1<br />

Winifred Raushenbush<br />

In <strong>the</strong> first week <strong>of</strong> June, 1924, a middle-aged missionary named J. Merle Davis<br />

paid a visit to <strong>the</strong> Chinatown <strong>of</strong> Fresno, California. The Chinatown was small, only a<br />

block or so along Tulare Street, and Davis would have had no trouble locating <strong>the</strong><br />

building for which he was looking. If it had been nighttime, he could have been guided<br />

by <strong>the</strong> brilliant neon sign which announced <strong>the</strong> Yet Far Low Restaurant, but even in<br />

<strong>the</strong> daylight by which he walked, <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> electric sign on <strong>the</strong> corner <strong>of</strong><br />

Tulare and China Alley was easily visible.<br />

Merle Davis was not a Californian. His fa<strong>the</strong>r had been an American missionary<br />

to Japan, and Davis had grown up <strong>the</strong>re. After graduating from college in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States, he had returned to Japan to serve as <strong>the</strong> Secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tokyo YMCA (Young<br />

Men's Christian Association), and only recently had Davis moved to <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

At this moment, he was on his way to meet Flora Belle Jan, <strong>the</strong> seventeen year old<br />

daughter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> man who owned <strong>the</strong> Yet Far Low chop suey restaurant. Though Jan’s<br />

family was well-<strong>of</strong>f by Chinatown standards, none <strong>of</strong> this wealth was apparent within<br />

<strong>the</strong> living quarters attached to <strong>the</strong> restaurant. It was crowded, dark and dirty, and to<br />

1 Winifred Raushenbush, "Address to Tentative Findings Conference, March 21-26,<br />

1925." Findings Conference Folder, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, Hoover<br />

Institution Archives, Stanford University.<br />

1

Davis, reeking <strong>of</strong> Chinatown smells. Within this humble home, Flora Belle Jan slept in a<br />

half l<strong>of</strong>t, one side <strong>of</strong> which was divided into a place for clucking hens.<br />

Davis was fascinated by <strong>the</strong> young woman. This was his second visit, and<br />

despite her surroundings, he saw enormous potential in her. Jan was witty, poised and<br />

talkative, with a penchance for being "modern" and "unconventional" in <strong>the</strong> manner <strong>of</strong><br />

a young flapper. Armed with a vivacious intelligence and imagination, she had<br />

ambitions to be a writer, and several <strong>of</strong> her stories had been published in William<br />

Randolph Hearst’s prestigious San Francisco Examiner. During his visit, Davis chatted<br />

with Jan about her parents’ disapproval <strong>of</strong> her conduct, and how she was afraid that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would not support her wish to attend Berkeley and fur<strong>the</strong>r her career.<br />

Afterwards, he left convinced that with <strong>the</strong> “right handling and leadership she might<br />

make a great deal <strong>of</strong> herself and become a real help to her own people.” 2<br />

What was going on here? Why was this missionary from Boston through Japan<br />

so interested in this young Chinese American flapper in Fresno? From this initial<br />

location in <strong>the</strong> Yet Far Low chop suey restaurant in Fresno, I would like to fan out in a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> directions and answer certain questions. How did it happen that J. Merle<br />

Davis, and behind him a network <strong>of</strong> American Protestant missionaries, came to this<br />

2 Descriptions and quotes are from letters, J. Merle Davis to Robert E. Park, June 1 and<br />

June 5, 1924. J. Merle Davis Correspondence Files, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race<br />

Relations, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University. Biographical information<br />

on J. Merle Davis from his correspondence and from his biography <strong>of</strong> his fa<strong>the</strong>r, Soldier<br />

Missionary: A Biography <strong>of</strong> Rev. Jerome D. Davis, D.D., Lieutenant-Colonel <strong>of</strong> Volunteers and<br />

for Thirty-Nine Years a Missionary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American Board <strong>of</strong> Commissioners for Foreign<br />

Missions in Japan (Boston: The Pilgrim Press, 1916). For more on Flora Belle Jan, see<br />

<strong>the</strong> extensive research on her in Judy Yung’s Unbound Feet: A Social <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chinese<br />

American Women in San Francisco (Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California Press, 1995).<br />

2

small Chinatown in California? What did he see in her? And what did his interest have<br />

to do with <strong>the</strong> American institutions <strong>of</strong> Orientalism in <strong>the</strong> 1920's?<br />

This essay will trace how American missionaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> YMCA International<br />

connected <strong>the</strong> conversion <strong>of</strong> "Orientals' in Asia with <strong>the</strong> sociological study <strong>of</strong> 'Orientals'<br />

in America. 3 Beginning with <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

3 I use <strong>the</strong> term "Oriental" not because I condone its use as a name or marker, but<br />

because it reflects a specific historic usage and category. The current usage for people<br />

who can trace <strong>the</strong>ir heritage back to Asia or <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Ocean is "Asian <strong>Pacific</strong> Islanders,"<br />

a label which encompasses Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Samoan, Hawaiian,<br />

Vietnamese, Cambodian, Thai, Indonesian and o<strong>the</strong>r such ancestry. The term "Asian<br />

American," which replaced "Oriental" in <strong>the</strong> 1970's, still works as a more pleasant and<br />

politically useful label for many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same people who were formerly known as<br />

"Orientals." There has been a voluminous literature on <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> term<br />

"Oriental," spurred especially by Edward Said's Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1978).<br />

For a larger discussion <strong>of</strong> American "Orientalism," particularly in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> social<br />

scientific definitions, see Henry Yu, Thinking About 'Orientals:' Race, Migration and <strong>the</strong><br />

Production <strong>of</strong> Exotic Knowledge in Modern America (Oxford University Press, manuscript in<br />

progress). Relatedly, I use <strong>the</strong> term "white" for that constellation <strong>of</strong> people who benefit<br />

from inclusion into <strong>the</strong> category <strong>of</strong> "whiteness" by being defined as different from those<br />

Americans <strong>of</strong> "color." For <strong>the</strong> central role <strong>of</strong> race in American history, see Michael Omi<br />

and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in <strong>the</strong> United States (New York: Routledge, 1986).<br />

See David Roediger, The Wages <strong>of</strong> Whiteness: Race and <strong>the</strong> Making <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American Working<br />

Class (London: Verso, 1991); Tomás Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins <strong>of</strong><br />

White Supremacy in California (Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California Press, 1994); Alexander<br />

Saxton, The Rise and Fall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> White Republic (London: Verso, 1990); Virginia<br />

Dominguez, White by Definition (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986) for<br />

3

United States between 1923 and 1926, and continuing through <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Relations in 1926, a network <strong>of</strong> American missionaries and social<br />

scientists criss-crossed Asia, America, and Hawaii, producing knowledge about <strong>the</strong><br />

relations between people living at each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se locations. In <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

explorations <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong>y labelled <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Rim</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y created a body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ories about<br />

<strong>the</strong> differences between 'Orientals' and 'Occidentals.' 4 Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> American<br />

missionaries and sociologists would entrench <strong>the</strong>ir scholarly discourse within a set <strong>of</strong><br />

academic and funding institutions which would disseminate and reproduce <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

interesting discussions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> "whiteness" as a social, legal, and economic<br />

category.<br />

4 The term "<strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Rim</strong>" achieved a currency in <strong>the</strong> 1980's, due in large part to <strong>the</strong> rising<br />

awareness <strong>of</strong> economists and policy experts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> Asian economies and <strong>the</strong><br />

declining role <strong>of</strong> American trade with Europe. West coast cities such as Seattle, San<br />

Francisco, and Los Angeles were seen to be <strong>the</strong> economic future <strong>of</strong> America, connected<br />

to <strong>the</strong> rising trade centers <strong>of</strong> Tokyo, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Singapore. The rise in<br />

Asian versus European immigration to <strong>the</strong> U.S. in <strong>the</strong> decades since <strong>the</strong> immigration<br />

reform or 1965 also contributed to an awareness that it would be Asian connections and<br />

culture which would define America's future. The most popular rendition <strong>of</strong> this shift<br />

from Eurocentrism to Asiacentrism was Frank Gibney's television series and book,The<br />

<strong>Pacific</strong> Century: America and Asia in a Changing World (New York: Scribner's, 1992).<br />

Though missionaries and sociologists in <strong>the</strong> 1920's occasionally used <strong>the</strong> term <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

<strong>Rim</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y also used phrases such as <strong>Pacific</strong> Basin, with no singular term achieving <strong>the</strong><br />

popular usage which <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Rim</strong> had in <strong>the</strong> 1980's. See <strong>the</strong> various essays highly critical<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recent usage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> term <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Rim</strong> in Arif Dirlik, editor, What is in a <strong>Rim</strong>? Critical<br />

Perspectives on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Region Idea (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993).<br />

4

definitions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 'Orient.' 5 This essay examines how American institutions <strong>of</strong><br />

'Orientalism' arose in <strong>the</strong> 1920's, putting in place definitions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great physical and<br />

cultural "distance" between 'Orientals' and 'Americans' which would have long term<br />

effects on how Asians were understood within American academia for <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

twentieth-century.<br />

Our first question concerns what <strong>the</strong> missionary J. Merle Davis was doing in<br />

California. He had been sent on a reconnaissance trip to <strong>the</strong> West Coast by <strong>the</strong> Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Social and Religious Research, a New York-based organization which channelled<br />

Rockefeller Foundation money into what it deemed worthy social research projects.<br />

Run by a number <strong>of</strong> Protestant ministers with a deep concern over social welfare and<br />

<strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> religiousity in <strong>the</strong> United States (<strong>the</strong>y were <strong>of</strong>ten connected with <strong>the</strong> label<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘social gospel’), <strong>the</strong> Institute’s stated purpose was to finance scientific research which<br />

would serve <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> social reform. 6 One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Institute’s key members was John R.<br />

Mott, a leader in <strong>the</strong> YMCA movement in <strong>the</strong> United States, and <strong>the</strong> founder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

YMCA International. The YMCA movement had been planned in <strong>the</strong> last two decades<br />

5 For <strong>the</strong> relationship between power and knowledge, see Michel Foucault, The Order <strong>of</strong><br />

Things: An Archaelogy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1973), andThe <strong>History</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Sexuality , Volumes One and Two (New York: Vintage, 1990); and Edward Said,<br />

Orientalism .<br />

6 The Institute was also at that time funding Robert and Helen Lynd’s research in<br />

Muncie, Indiana which would result in <strong>the</strong>ir famous book, Middletown: A Study In<br />

American Culture (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1929). On <strong>the</strong> missionaries'<br />

internal histories <strong>of</strong> John Mott and <strong>the</strong> YMCA movement, see Galen M. Fisher, John R.<br />

Mott: Architect <strong>of</strong> Cooperation and Unity (New York: 1952) and Citadel <strong>of</strong> Democracy: The<br />

Story <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Affairs Record <strong>of</strong> Stiles Hall (Berkeley: The YMCA <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong><br />

California, 1955).<br />

5

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 19th-century as an attempt to make Christianity a practical element <strong>of</strong> everyday<br />

modern life, targeting <strong>the</strong> urban centers <strong>of</strong> America and <strong>the</strong> world. The mission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

YMCA was to promote goodwill and harmony through institutions which organized<br />

social activities that encouraged fair play and cooperation. As an act <strong>of</strong> 'social gospel,'<br />

<strong>the</strong> YMCA was an attempt to expand religiousity from a private, individual orientation<br />

into <strong>the</strong> social acts <strong>of</strong> everyday life.<br />

In 1922, several YMCA missionaries who had returned from Japan pressed for a<br />

research survey into <strong>the</strong> widespread anti-Japanese agitation on <strong>the</strong> West Coast. 7<br />

George Gleason, <strong>the</strong> secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> YMCA in Los Angeles, and Galen Fisher, <strong>the</strong><br />

secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Institute in New York, had both worked in an earlier time at <strong>the</strong> YMCA<br />

in Tokyo, and along with Davis <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>of</strong> a generation <strong>of</strong> highly trained and<br />

devoted ministers who had answered John Mott’s call to promote international<br />

understanding and goodwill through foreign missions. To <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> increasingly<br />

strident calls for Japanese exclusion in California and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pacific</strong> states demanded<br />

attention. Davis, <strong>the</strong>refore, had been sent to <strong>the</strong> West Coast to find out what could be<br />

done.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> first anti-Chinese riots <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1870’s, Protestant missionaries had been<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few allies <strong>of</strong> Asian immigrants in <strong>the</strong> United States. Concurrent with <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

7 Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, already cited, Boxes 11-14. Surveys had<br />

become a popular research and social reform device at <strong>the</strong> time, particularly after <strong>the</strong><br />

Pittsburgh Survey, a large scale effort carried out between 1909 and 1914 which<br />

investigated <strong>the</strong> conditions <strong>of</strong> industrial workers in that city. Considering topics such as<br />

health, sanitation, housing, wages, industrial accidents, education, crime, juvenile<br />

delinquency, and o<strong>the</strong>r social conditions, <strong>the</strong> Pittsburgh Survey became a model for<br />

reform-minded research. Paul Kellogg Papers, Social Welfare Archives, University <strong>of</strong><br />

Minnesota.<br />

6

Far Eastern missions, Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians had set up missions to<br />

‘hea<strong>the</strong>ns’ within America itself. Beyond <strong>the</strong> goals <strong>of</strong> conversion and saving souls,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se missionaries were also concerned with <strong>the</strong> social welfare <strong>of</strong> immigrants. The<br />

missionaries believed that <strong>the</strong> numerous laws passed by state and federal legislatures<br />

which discriminated against ‘Asiatics’ in America made <strong>the</strong>ir work in Asian countries<br />

more difficult; however, despite <strong>the</strong> fact that it was in <strong>the</strong>ir own interests to lessen <strong>the</strong><br />

harsh treatment <strong>of</strong> ‘Orientals’ in America, <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ condemnations <strong>of</strong><br />

American injustice were none<strong>the</strong>less heartfelt. 8<br />

The missionaries had a long history <strong>of</strong> involvement in <strong>the</strong> effort to counter anti-<br />

Asian agitation. For example, <strong>the</strong> most prominent friend <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese in <strong>the</strong><br />

country, <strong>the</strong> Reverend Sidney Gulick, had been born in Japan and by <strong>the</strong> 1920's had<br />

spent <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> his life <strong>the</strong>re. As Oriental Secretary for <strong>the</strong> Federal Council <strong>of</strong><br />

Churches <strong>of</strong> Christ in America, he had published a series <strong>of</strong> pamphlets and books<br />

attacking restrictive American immigration and land-owning legislation in regard to<br />

Asians, and calling for equal and just treatment <strong>of</strong> immigrants and aliens regardless <strong>of</strong><br />

race, color or religion. 9 The Federal Council, as an umbrella organization <strong>of</strong> Protestant<br />

evangelical churches, was internationalist in orientation. Besides immigration reform, it<br />

had tried to promote "friendly relations" between <strong>the</strong> United States and Asian<br />

8 Elmer Clarence Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Urbana:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Illinois Press, 1939), 35-36. Also see Wesley Woo, “Protestant Work<br />

Among <strong>the</strong> Chinese in <strong>the</strong> San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1920,” Unpublished PhD<br />

dissertation, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, 1983.<br />

9 The American Japanese Problem: A Study <strong>of</strong> The Racial Relations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> East and <strong>the</strong> West<br />

(New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1914) Gulick also wrote a book emphasizing <strong>the</strong> danger to<br />

American ideals which mistreatment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chinese and Japanese presented, American<br />

Democracy and Asiatic Citizenship (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1918).<br />

7

countries by calling for such acts as <strong>the</strong> elimination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> opium trade, universal<br />

disarmament, and Philipine independence. Both Sidney Gulick and J. Merle Davis were<br />

solidly esconced within a network <strong>of</strong> ‘social gospel’ ministers and missionaries which<br />

composed <strong>the</strong> Federal Council <strong>of</strong> Churches <strong>of</strong> Christ, <strong>the</strong> American Board <strong>of</strong> Foreign<br />

Missions, <strong>the</strong> YMCA and YWCA, and <strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Social and Religious Research.<br />

By <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> 1923, Davis had decided that <strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Social and Religious<br />

Research should pledge $55,000 towards a Survey on Race Relations on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong><br />

Coast. This ambitious effort was aimed at not only discovering <strong>the</strong> facts about <strong>the</strong><br />

"racial situation" in <strong>the</strong> West, but also at bringing pro- and anti-Asian groups toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

in a united research project. 10 Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> political polarization and hostility over <strong>the</strong><br />

desirability <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ immigration, Davis believed that just getting <strong>the</strong> two sides to<br />

talk would be a difficult endeavor. But in accordance with <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ larger aims<br />

<strong>of</strong> good-will and peaceful reconciliation, he felt that <strong>the</strong> bringing toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

opposing sides into a mutual dialogue about ‘objective’ facts would be one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest accomplishments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey. 11<br />

10 Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, Box 11. The Institute was to pay $30,000 <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey, and it was hoped that private fund-raising on <strong>the</strong> West Coast<br />

would cover <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r $25,000. No funds were to be taken from Japanese or Chinese<br />

organizations in <strong>the</strong> United States though, since <strong>the</strong> Institute was afraid that such<br />

money would taint <strong>the</strong> neutral reputation which <strong>the</strong> survey was seeking.<br />

11 “[W]e can, I believe, make this survey one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> big Christian works <strong>of</strong> this year on<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole West Coast. This survey will, we believe, set a precedent for dealing with<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole terrific race question. It will also, Galen, be a contribution, if not an original<br />

contribution, to <strong>the</strong> whole question <strong>of</strong> approaching any serious problem on which<br />

opinions differ.” Letter from George Gleason to Galen Fisher, May 17, 1923, Gleason<br />

Correspondence, Box 11, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey.<br />

8

Davis recognized that <strong>the</strong> missionaries and <strong>the</strong> nativists had more than opposing<br />

sympathies in regard to ‘Orientals,’ <strong>the</strong>y also had vastly different backgrounds. In<br />

private letters, <strong>the</strong> missionaries pinned <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> anti-‘Oriental’ sentiments on<br />

several traits <strong>of</strong> West Coast ‘whites’: <strong>the</strong>ir general lack <strong>of</strong> education, <strong>the</strong>ir origins in <strong>the</strong><br />

American South or Catholic Ireland, and <strong>the</strong>ir ignorance <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ culture. It was<br />

no coincidence that <strong>the</strong> Protestant ministers associated with <strong>the</strong> survey had <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

all been college educated, had all originated from <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>astern United States, and<br />

had all spent significant time in <strong>the</strong> ‘Orient.’ 12<br />

Curiously, <strong>the</strong> missionaries believed that <strong>the</strong>ir backgrounds in dealing with <strong>the</strong><br />

subtleties <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ culture made <strong>the</strong>m uniquely qualified to overcome <strong>the</strong> divisions<br />

between differing groups on <strong>the</strong> West Coast. In recommending his friend Merle Davis<br />

to lead <strong>the</strong> survey, George Gleason pointed to <strong>the</strong> time which all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m had spent in<br />

Japan:<br />

The large unanimity <strong>of</strong> desire to have, as far as possible, labor unions, <strong>the</strong><br />

American Legion, chambers <strong>of</strong> commerce, as well as religious and educational<br />

bodies combine in <strong>the</strong> survey, makes it very necessary to have an executive<br />

head who possesses <strong>the</strong> kind <strong>of</strong> tact which years <strong>of</strong> experience in Japan seem to<br />

develop in us. I question whe<strong>the</strong>r any man on <strong>the</strong> Coast, or any ordinary man<br />

who has not lived in <strong>the</strong> Far East, could do <strong>the</strong> job that needs to be done. 13<br />

12 Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey, Box 11, Davis Correspondence, letters between Merle Davis,<br />

George Gleason, Hugo Guy, and Galen Fisher.<br />

13 Letter from Gleason to Fisher, April 20, 1923, Davis Correspondence, Box 11, Papers<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey.<br />

9

The missionaries believed that <strong>the</strong>y knew <strong>the</strong> Japanese from first-hand<br />

experience, and <strong>the</strong>y remembered how frustrating and difficult it could be to deal with<br />

‘Orientals’ whom <strong>the</strong>y thought might take <strong>of</strong>fense at <strong>the</strong> slightest mistake. They<br />

blamed <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fenses, <strong>of</strong> course, on <strong>the</strong> strict demands <strong>of</strong> social etiquette and politeness<br />

which Japanese society demanded, and not on <strong>the</strong> difficulties <strong>of</strong> cross cultural relations,<br />

or even <strong>the</strong>ir own penchance for social miscues. In <strong>the</strong> end, <strong>the</strong>y felt that after dealing<br />

with such an exotic and intricate society as <strong>the</strong> Japanese, handling <strong>the</strong> nativists would be<br />

relatively easy.<br />

Who’s Oriental and What’s <strong>the</strong> Problem<br />

“Is <strong>the</strong>re an Oriental Problem in America? If so, where is it? What are its<br />

manifestations? What do we know <strong>of</strong> our Chinese, East Indians, Filipinos, and<br />

Japanese? How do <strong>the</strong>y contribute to our wealth and welfare? To what extent<br />

are our impressions in accordance with <strong>the</strong> facts? These are some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

questions which The Survey <strong>of</strong> Race <strong>of</strong> Relations is trying to answer.” 14<br />

In setting out to research race relations on <strong>the</strong> West Coast, both missionaries and<br />

nativists agreed that <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental problem’ was <strong>the</strong> central concern. But who was an<br />

‘Oriental’? And what was <strong>the</strong> ‘problem’?<br />

The answers to <strong>the</strong>se questions, not<br />

surprisingly, depended upon who was being asked. For <strong>the</strong> Japanese Exclusion<br />

League, <strong>the</strong> Sons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Golden West, <strong>the</strong> American Legion, and o<strong>the</strong>r nativist<br />

organizations, ‘Oriental’ was a racial classification bounded not only by presumed<br />

origins in Asia and <strong>the</strong> Far East (<strong>the</strong> mythical Orient), but it also reflected a history <strong>of</strong><br />

14 “The Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations,” Eliot Grinnel Mears, The Stanford Illustrated Review<br />

(April, 1925). Reprint found in Box 5 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations.<br />

10

struggles over <strong>the</strong> threat to ‘whites’ <strong>of</strong> cheap labor. Labor organizations and<br />

unionizers had portrayed Chinese ‘coolie’ workers during <strong>the</strong> late 19th-century as <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest threat to ‘free labor’ (‘free’ as opposed to ‘enslaved’), excluding <strong>the</strong>m from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir organizational efforts and using <strong>the</strong>m as <strong>the</strong> whip to bring ‘white’ labor into<br />

line. 15 By 1923, <strong>the</strong> Chinese had been so effectively excluded from most occupations<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y were no longer considered a threat. But <strong>the</strong> nativist rhetoric <strong>of</strong> a ‘yellow<br />

peril’ and <strong>the</strong> danger <strong>of</strong> ‘Orientals’ to America rested largely upon <strong>the</strong> continuing<br />

memory <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong> Chinese ‘problem’ was overcome. When large numbers <strong>of</strong><br />

Japanese immigrants came to <strong>the</strong> West Coast at <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> century, , <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

designated easily as <strong>the</strong> latest "Oriental invasion."<br />

Anti-Japanese organizations pointed to what <strong>the</strong>y saw as unnaturally productive<br />

farming practices as an indication that <strong>the</strong> growing numbers <strong>of</strong> Japanese were about to<br />

take over <strong>the</strong> West. Just like <strong>the</strong> Chinese before <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> Japanese were portrayed as<br />

unfair competition because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir work habits and <strong>the</strong>ir ability to endure hardship and<br />

sacrifice, threatening to crowd out helpless ‘white’ workers and farmers who could not<br />

compete. Worse still, <strong>the</strong> nativists were frustrated by <strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

15 For discussions <strong>of</strong> how ‘whiteness’ was constructed with <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> racialized labor<br />

divisions, see Alexander Saxton, The Indispensible Enemy: Labor and The Anti-Chinese<br />

Movement in California (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> California Press, 1971);<br />

Saxton, The Rise and Fall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> White Republic, Chapter 12 and 13; Roediger, The Wages<br />

<strong>of</strong> Whiteness; and Ron Takaki, Iron Cages: Race and Culture in 19th-Century America<br />

(New York: Knopf, 1979). On <strong>the</strong> images <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Orient which Americans connected to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Chinese, see Stuart Creighton Miller, The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chinese, 1785-1882 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> California Press,<br />

1969) in particular Chapter 8. For a good general discussion <strong>of</strong> anti-Asian hostility,<br />

Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive <strong>History</strong> (Boston: Twayne, 1991).<br />

11

government in protecting Japanese nationals in <strong>the</strong> United States. Unlike <strong>the</strong> Chinese<br />

government, which had been relatively powerless to stop <strong>the</strong> Chinese Exclusion Act <strong>of</strong><br />

1882, <strong>the</strong> Japanese government had been able to forestall any federal legislation in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States which was discriminatory against Japanese immigrants. The Gentlemen’s<br />

Agreement in 1907 between Japan and <strong>the</strong> United States had <strong>the</strong> appearance <strong>of</strong> a<br />

voluntary act made by <strong>the</strong> Japanese to limit <strong>the</strong>ir emigration to <strong>the</strong> U.S., and nativist<br />

groups in <strong>the</strong> West universally called for a strong federal exclusion act; successful anti-<br />

Japanese legislation up until <strong>the</strong> 1920’s, though, had almost all been on <strong>the</strong> state level. 16<br />

Not until <strong>the</strong> new federal immigration laws <strong>of</strong> 1924, which excluded Asians from entry<br />

into America, did <strong>the</strong> U.S. government seem to act against <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental invasion.’<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> conspiracy <strong>the</strong>ories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nativists, <strong>the</strong> ‘Mikado’ or Japanese<br />

16 The Gentlemen's Agreement was atypical to that point in diplomatic relations<br />

between Western and Asian powers because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recognition gained by <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

government that <strong>the</strong>y were relatively 'equal' to Western nations, a status won by <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

victory over a 'white' nation in <strong>the</strong> Russo-Japanese War in 1904. Treatments <strong>of</strong> anti-<br />

Japanese legislation can be found in Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese<br />

in <strong>the</strong> United States since 1850 (Seattle: University <strong>of</strong> Washington Press, 1988) and<br />

Jacobus tenBroek, et. al., Prejudice, War and <strong>the</strong> Constitution: Causes and Consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Evacuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese Americans in World War II (Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong><br />

California Press, 1954). Discussions <strong>of</strong> anti-Chinese legislation can be found in Charles<br />

J. McClain, In Search <strong>of</strong> Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discrimination in Nineteenth-<br />

Century America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> California Press, 1994) and<br />

Sucheng Chan, editor, Entry Denied: Exclusion and <strong>the</strong> Chinese Community in America,<br />

1882-1943 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991)<br />

12

Emperor was <strong>the</strong> ultimate fount <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘yellow peril’ and served as a symbol for <strong>the</strong><br />

effective opposition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese government to federal laws against <strong>the</strong> Japanese. 17<br />

The tendency <strong>of</strong> nativist and labor groups to link racial definitions <strong>of</strong> ‘Orientals’<br />

with perceived economic conflicts led to <strong>the</strong> extension <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ classification to East<br />

Indian and Filipino migrant agricultural workers, even though during <strong>the</strong> early 1920’s<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir absolute numbers were miniscule compared to Chinese and Japanese in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States. To <strong>the</strong> undiscerning eye which could not tell a “Chinaman” from a<br />

“Jap,” <strong>the</strong> perceived visual difference between ‘traditional Orientals’ and <strong>the</strong> East<br />

Indians and Filipinos was bridged by <strong>the</strong>ir similar economic threat. During <strong>the</strong> early<br />

days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, Davis even responded to <strong>the</strong> suggestions <strong>of</strong> labor<br />

leaders to consider including Mexicans in <strong>the</strong> survey’s purview, since <strong>the</strong>y were seen as<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> larger ‘racial’ labor forces. However, he eventually decided that <strong>the</strong><br />

definition <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ would not stretch that far, and so <strong>the</strong> practical focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

survey was to be <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental problem.’ 18<br />

17 One labor leader responded to Davis’ suggestion for an impartial research survey<br />

with <strong>the</strong> accusation: “I know who you are and where you come from. You are from<br />

Japan and a spy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mikado. . . This Survey is loaded with religion and capital. Who’s<br />

going to pay for it anyway? Capital. The capitalists will pay for it and <strong>the</strong> church will<br />

run it and ei<strong>the</strong>r way labor will get flimflammed.” Though sounding slightly paranoid,<br />

<strong>the</strong> accusation had some truth to it: Davis was from Japan and <strong>the</strong> money did come<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Rockefeller Foundation. Quote from Winifred Raushenbush, Robert E. Park:<br />

Biography <strong>of</strong> a Sociologist (Durham: Duke University Press, 1979), 108; originally found<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations.<br />

18 Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey, Box 11, Davis Correspondence. The terms ‘Asiatic’ and<br />

‘Oriental,’ though sometimes interchangeable, could also refer to different<br />

conglomerations <strong>of</strong> people. For instance, <strong>the</strong> USC sociologist Emory Bogardus<br />

13

The survey’s focus upon ‘Orientals’ had much to do with its missionary<br />

organizers. Davis, Gleason, and Fisher had begun <strong>the</strong>ir project because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

background in Japan and <strong>the</strong>ir concern over anti-Japanese agitation; <strong>the</strong>y had only<br />

expanded <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey to include <strong>the</strong> Chinese at a much later date.<br />

Strangely, this expansion was less in response to labor leaders, who no longer had<br />

much ‘problem’ with <strong>the</strong> Chinese, but to <strong>the</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>r missionaries who worked<br />

among <strong>the</strong> Chinese in both China and <strong>the</strong> United States. The definition <strong>of</strong> who in <strong>the</strong><br />

end was an ‘Oriental’ was intimately connected with <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ interest in <strong>the</strong><br />

Orient as <strong>the</strong> geographical location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir mission. They empathized with ‘Orientals’<br />

in America because <strong>the</strong>y viewed <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> same way that <strong>the</strong>y viewed ‘Orientals’ in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Orient, as potential converts. Organizations such as <strong>the</strong> YMCA International and<br />

<strong>the</strong> American Board <strong>of</strong> Foreign Missions pr<strong>of</strong>essed a global vision <strong>of</strong> not only<br />

Christianization but Americanization, spreading <strong>the</strong> ‘good word’ about <strong>the</strong> American<br />

way <strong>of</strong> life, which <strong>the</strong>y saw as a concurrent goal. The Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations was<br />

only one step towards <strong>the</strong> remaking <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental’ at home, but it fit into <strong>the</strong><br />

broader attempt <strong>of</strong> remaking <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental’ abroad. In his justification for <strong>the</strong> necessity<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey, George Gleason explained <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> returned missionaries who<br />

were on <strong>the</strong> west coast:<br />

referred in 1919 to “Asiatic immigrants” by including Armenians and Syrians from<br />

“Western Asia” toge<strong>the</strong>r with Chinese and Japanese from “Eastern Asia.” By <strong>the</strong><br />

Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations five years later, he was referring more specifically to Chinese<br />

and Japanese as “Oriental immigrants.” The point is that <strong>the</strong> boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

definitions changed through time with <strong>the</strong> contexts and situations <strong>of</strong> usage. Emory S.<br />

Bogardus, Essentials <strong>of</strong> Americanization (Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California<br />

Press, 1919, 2nd edition, 1920), 201.<br />

14

It is up to us in this country to find <strong>the</strong> right way to handle <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

problems out here. To do this requires first <strong>of</strong> all more accurate knowledge than<br />

we now possess. After this knowledge is secured, political action and Christian<br />

Americanization efforts must follow. 19<br />

The inclusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chinese within <strong>the</strong> purview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey also had much to<br />

do with <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental problem.’ For <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> ‘problem’<br />

lay not with <strong>the</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> Chinese and Japanese labor, but with West Coast ‘whites’<br />

and <strong>the</strong> terrible treatment which <strong>the</strong>y accorded ‘Orientals’ in America. 20 Davis,<br />

Gleason, Fisher, and Gulick had all known Christianized ‘Orientals’ in Japan, and many<br />

converted ‘Orientals’ had ultimately come to <strong>the</strong> United States. The ‘conversion’ <strong>of</strong><br />

‘Orientals’ linked up to <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ability to be assimilated into American life,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> missionaries truly believed that if <strong>the</strong> American public could come to see<br />

‘Orientals’ as <strong>the</strong>y did, as potential and successful converts to Christianity and<br />

Americanism, <strong>the</strong>n all would be well. The economic threat <strong>of</strong> ‘Oriental’ labor was a<br />

non-issue once ‘Orientals’ were recognized as fellow Christians and Americans.<br />

19 Gleason to Davis, October 28, 1922, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey, Box 11.<br />

20 Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> missionaries were quite pessimistic about <strong>the</strong> potential success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

survey in ameliorating this ill-treatment <strong>of</strong> ‘Orientals.’ Harvey H. Guy <strong>of</strong> Berkeley,<br />

California, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> returned missionaries from Japan, referred to <strong>the</strong> impending<br />

exclusion legislation against Asians using <strong>the</strong> language <strong>of</strong> a pathologist: “[T]he case<br />

looks very bad. As a friend <strong>of</strong> mine said about <strong>the</strong> Survey, it looks like our<br />

investigations will be too late, <strong>the</strong> diagnosis has become an autopsy. But. . . we may<br />

learn something even from a corpse, so we must go on with <strong>the</strong> Survey.” Letter from<br />

Guy to Davis, November 26, 1923. Box 11, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey.<br />

15

In an attempt to dispel <strong>the</strong> illusion that <strong>the</strong>re was a ‘yellow peril’ in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States and that Asians were “unassimilable,” <strong>the</strong> Reverend Sidney Gulick had included<br />

in his book The American Japanese Problem chapters answering ‘Yes’ to questions such<br />

as “Are Japanese Assimilable?” and “Can Americans Assimilate Japanese?” Examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘assimilability’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese centered around ‘Americanized’ Japanese<br />

children in Christian homes and schools in America, complete with pictures <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m in<br />

American dress and hair-styles. Proudly, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> picture captions announced that<br />

<strong>the</strong> “American-Japanese” man in <strong>the</strong> photograph could “speak no Japanese” and was<br />

a graduate <strong>of</strong> Yale--obvious pro<strong>of</strong> that he had reached <strong>the</strong> pinnacle <strong>of</strong> ‘white, anglosaxon,<br />

Protestant’ achievement in America. 21 Even <strong>the</strong> reference to ‘American<br />

Japanese’ ra<strong>the</strong>r than Japanese American was a calculated attempt at emphasizing <strong>the</strong><br />

‘American’ ra<strong>the</strong>r than ‘Japanese’ nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> young man.<br />

Outward signs such as clothing and hair style became <strong>the</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> outright<br />

assimilation, since <strong>the</strong>y signified <strong>the</strong> ‘loss’ <strong>of</strong> traditional dress and speech. Gulick and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r pro-Japanese writers <strong>of</strong>ten used <strong>the</strong>se signs as a rhetorical weapon to combat <strong>the</strong><br />

fears <strong>of</strong> anything less than ‘100% Americanism’ which <strong>the</strong> nativist organizations were<br />

propagating. 22 Americanization was a focal term in <strong>the</strong> debate which surrounded <strong>the</strong><br />

image <strong>of</strong> America as a ‘melting pot,’ and as we shall see, <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> ‘assimilation’<br />

became <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental problem.’ For <strong>the</strong> missionaries, a key claim for <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

argument against nativist groups such as <strong>the</strong> American Legion and <strong>the</strong> Sons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Golden West was that ‘Orientals’ were in fact ‘assimilable’ to American life, as proven<br />

21 Gulick, The American Japanese Problem, cited above, 220.<br />

22 The best study <strong>of</strong> 19th-Century American nativism remains John Higham, Strangers<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Land: Patterns <strong>of</strong> American Nativism, 1860-1925 (New Brunswick: Rutgers<br />

University Press, 1955)<br />

16

y <strong>the</strong>ir adoption <strong>of</strong> superficial signs <strong>of</strong> Americanization such as clothing, speech, and<br />

hair-style. American manners and Christian beliefs would surely follow.<br />

The fascination <strong>of</strong> Merle Davis with Flora Belle Jan, <strong>the</strong> young daughter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

chop suey restauranteur, fit into <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ interest with symbols <strong>of</strong> effective<br />

assimilation. Jan was American-born, had <strong>the</strong> mannerisms <strong>of</strong> a young American<br />

flapper, and proved to all who met her that she was not like <strong>the</strong> typical ‘Oriental.’ As<br />

Davis gushed, Jan was “<strong>the</strong> only Oriental in town apparently who has <strong>the</strong> charm, wit<br />

and nerve to enter good White society. She has been accepted...” 23 In <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong><br />

Davis, Flora Belle Jan was <strong>the</strong> perfect embodiment <strong>of</strong> successful Americanization, and as<br />

such was <strong>the</strong> very type <strong>of</strong> person for which <strong>the</strong> survey was searching. For <strong>the</strong>se<br />

reasons, she would be used over and over again as an exemplar that successful<br />

assimilation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Oriental’ was going on in America.<br />

The difference, in <strong>the</strong> end, between <strong>the</strong> nativists' definition and <strong>the</strong> missionaries'<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 'Oriental problem' was that <strong>the</strong> nativists' believed that <strong>the</strong> 'Orientals'<br />

were <strong>the</strong> problem, and <strong>the</strong> missionaries believed that <strong>the</strong> nativists were <strong>the</strong> problem.<br />

In trying to bring everyone concerned toge<strong>the</strong>r during <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations,<br />

<strong>the</strong> missionaries recruited a group <strong>of</strong> sociologists as experts who could study <strong>the</strong><br />

problems in an "scientific" manner. For <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong> 'Oriental problem' was limited<br />

nei<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>the</strong> 'Orientals' nor <strong>the</strong> nativists; according to <strong>the</strong> sociologists, <strong>the</strong> missionaries<br />

were part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem, too.<br />

A Pr<strong>of</strong>ession <strong>of</strong> Faith <strong>of</strong> a Different Order<br />

23 Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey, Box 11, Davis Correspondence, Davis to Robert E. Park, June<br />

1, 1924.<br />

17

During <strong>the</strong> early planning stages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, Merle Davis<br />

saw a way to overcome <strong>the</strong> gulf between <strong>the</strong> pro- and anti-‘Oriental’ forces: <strong>the</strong><br />

survey needed to bring in scientific experts who seemingly had no political stake in <strong>the</strong><br />

debate over Asian immigration. The experts would have to come from <strong>the</strong> outside,<br />

since some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> West Coast academic institutions such as Stanford University had<br />

become associated with pro-‘Oriental’ stands. 24 Davis felt as long as <strong>the</strong> surveyors<br />

could claim to be conducting ‘scientific’ research and merely ‘ga<strong>the</strong>ring facts,’ <strong>the</strong><br />

survey would appear politically neutral. 25 In public relations releases to <strong>the</strong> press, <strong>the</strong><br />

rewards for <strong>the</strong> special role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> universities and research experts in <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong><br />

Race Relations were touted repeatedly:<br />

Educators here believe that <strong>the</strong> race relations survey meeting has been one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> most important ga<strong>the</strong>rings in many years that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Coast has seen.<br />

The Survey, it is believed, has thrown more real light on <strong>the</strong> Asiatic situation, as<br />

it affects <strong>the</strong> Coast states, than has any o<strong>the</strong>r ga<strong>the</strong>ring in years. Educated<br />

24 David Starr Jordan at Stanford University was an outspoken defender <strong>of</strong> Chinese and<br />

Japanese immigrants, and <strong>the</strong>re had been a large controversy at <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

century when E.A. Ross, <strong>the</strong> prominent social scientist at Stanford, had been fired by<br />

Leland Stanford’s widow because <strong>of</strong> his open stand against Chinese and Japanese labor.<br />

Leland Stanford, though himself opposed to large-scale settlement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> West Coast<br />

by Asians, had <strong>of</strong> course made his fortune by using Chinese workers to build his<br />

railroads during <strong>the</strong> 1860’s.<br />

25 “[W]e are not only promoting <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> a survey <strong>of</strong> race relations, but we are also<br />

doing what may eventually prove <strong>the</strong> bigger thing--promoting <strong>the</strong> principle <strong>of</strong> an<br />

unbiased and scientific united approach, by all factions interested, to a controversial<br />

problem.” Gleason to Davis, March 11, 1924, Box 11, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey.<br />

18

persons experience a sense <strong>of</strong> relief when <strong>the</strong>y learn <strong>of</strong> any endeavors, entirely<br />

divorced from legislative programs or special formulas, which center about <strong>the</strong><br />

greatness <strong>of</strong> fact. 26<br />

The aura <strong>of</strong> knowledge and expertise which surrounded <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

university campus was one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rhetorical myths into which <strong>the</strong> surveyors wanted to<br />

tap. Like <strong>the</strong> shrine <strong>of</strong> a local Shinto deity, or a Catholic pilgrimmage site, <strong>the</strong><br />

university campus was a location suffused with powerful meanings: research, facts,<br />

learning, above all, knowledge. For those who believed in enlightenment through<br />

greater knowledge, <strong>the</strong> "scientific experts" from <strong>the</strong> hallowed ground <strong>of</strong> elite<br />

universities could make a rhetorical claim for <strong>the</strong> greatness <strong>of</strong> fact in a way in which<br />

<strong>the</strong> missionaries could not. A correspondent for <strong>the</strong> Chicago Daily News wrote on<br />

March 23, 1925:<br />

The Survey is looked upon as <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> a permanent surveillance <strong>of</strong><br />

interracial movements and contacts throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> Slope. Scholarship<br />

will inspire and control <strong>the</strong> work. The G.H.Q. [General Headquarters], in o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

words, will be in <strong>the</strong> universities.<br />

The grandiloquent claims <strong>of</strong> ‘real enlightenment’ and ‘surveillance’ <strong>of</strong> ‘racial<br />

movements’ were partly a product <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> missionaries’ desire for impartial factfinding,<br />

but <strong>the</strong>y also reflected <strong>the</strong> current image <strong>of</strong> social science. Although scientific<br />

sociology as an academic discipline was barely thirty years old, it had already carved<br />

out an impressive niche in almost all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elite universities <strong>of</strong> America. Perhaps <strong>the</strong><br />

most famous social scientist <strong>of</strong> those years was <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin’s E.A. Ross,<br />

26 March 26, 1925 edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> San Francisco Bulletin.<br />

19

<strong>the</strong> former Stanford University pr<strong>of</strong>essor and prominent Progressive Party intellectual<br />

who had advocated an instrumental role for social science in <strong>the</strong> control and progress <strong>of</strong><br />

society. 27 Ross and many <strong>of</strong> his contemporaries pioneered a vision <strong>of</strong> social science<br />

which shared a tenet with <strong>the</strong> missions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Protestant ministers--social reform<br />

planned and implemented by highly educated elites. 28 Indeed, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early<br />

27 Ross, who had written Social Control (New York: Macmillan, 1901), extolled <strong>the</strong><br />

power <strong>of</strong> social science in <strong>the</strong> aid <strong>of</strong> planned social reform. He was also one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sociologists with <strong>the</strong> most hierarchical conceptions <strong>of</strong> race. For <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> sociology as a<br />

discipline, see Mary Furner, Advocacy and Objectivity: A Crisis in <strong>the</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalization <strong>of</strong><br />

American Social Science, 1865-1905 (Lexington: University Press <strong>of</strong> Kentucky, 1975); and<br />

Dorothy Ross, The Origins <strong>of</strong> American Social Science (Cambridge: Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1991). In a ra<strong>the</strong>r complicated book, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> myriad things Ross<br />

does is to place <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> social science in <strong>the</strong> United States within <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> a<br />

language <strong>of</strong> ‘American exceptionalism,’ <strong>the</strong> end achievement being <strong>the</strong><br />

transformation by Park’s Chicago school <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> America as a ‘melting pot’ into<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘objective,’ ‘natural process’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘assimilation cycle.’<br />

28 The ‘enlightenment project’ <strong>of</strong> American social reformers at <strong>the</strong> turn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> century<br />

owed much to <strong>the</strong> European Enlightenment which spawned <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> social science,<br />

but its alliance with organized religion differed markedly from <strong>the</strong> ‘enlightenment’ <strong>of</strong><br />

Voltaire and Denis Diderot. The American social scientists scoured <strong>the</strong> European<br />

traditions for antecedents to <strong>the</strong>ir fledgling social science, and found <strong>the</strong> most<br />

conducive ‘fa<strong>the</strong>r figures’ in <strong>the</strong> Scottish Enlightenment (Adam Smith and Adam<br />

Ferguson), who were much less anti-clerical than <strong>the</strong> French philosophes. For a<br />

canonical discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘science <strong>of</strong> human society,’ see Peter Gay, The<br />

Enlightenment: An Interpretation, Volume II: The Science <strong>of</strong> Freedom (New York: Vintage,<br />

1969). It is interesting to contrast Gay’s reading <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> European Enlightenment with<br />

20

sociologists had been ministers or missionaries <strong>the</strong>mselves before converting to social<br />

science. The ties <strong>of</strong> social science and social work inspired by <strong>the</strong> ‘social gospel’<br />

remained strong. 29<br />

Enlightenment was a means to a better world, and <strong>the</strong> pursuit <strong>of</strong> knowledge<br />

about race relations on <strong>the</strong> West Coast was an end in itself. This goal reflected a belief<br />

in <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> learning, as well as a reflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deep faith which both Protestant<br />

Carl Becker’s The Heavenly City <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Eighteenth-Century Philosphers (New Haven: Yale<br />

University Press, 1932) which in comparison is a revealing reflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance<br />

which ‘progressive’ American thinkers placed upon religion and faith in both <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own ‘enlightenment’ and in <strong>the</strong>ir view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> 18th-century version.<br />

29 Chicago sociologist Ellsworth Faris was a former missionary and remained an<br />

ordained minister, and both Ernest Burgess and W.I. Thomas were <strong>the</strong> sons <strong>of</strong><br />

ministers. Robert Park was a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church <strong>of</strong> Edward Scribner Ames, a<br />

pragmatist philosopher at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Chicago and a prominent minister <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

‘social gospel.’ Both Albion Small and Charles Henderson, early members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Chicago department, saw sociology as a science in service <strong>of</strong> social problems, and <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sociology was an important ally <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Social Work and<br />

Administration which was housed across <strong>the</strong> Midway from sociology’s Harper Hall.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> twentieth-century, Ernest Burgess and Louis Wirth both had close<br />

connections to <strong>the</strong> social workers at <strong>the</strong> school founded by Edith Abbot and<br />

Sophonisbia Breckenridge, a reflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir deep interest in immigrant adjustments.<br />

Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most famous ‘social work’ institution which social scientists at Chicago<br />

became associated with was Jane Addams’ Hull House Settlement. See Robert E. L.<br />

Faris, Chicago Sociology, 1920-1932 (San Francisco: Chandler, 1967) for a description <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> missionary background <strong>of</strong> Chicago sociology. Robert Faris was <strong>the</strong> son <strong>of</strong><br />

Ellsworth Faris, and a sociology student at Chicago during those years.<br />

21

missionaries and social scientists had in <strong>the</strong> socially regenerative power <strong>of</strong> applied<br />

knowledge. We cannot understand <strong>the</strong> project <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> social scientists without putting it<br />

within <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> religious reformers who shared such similar backgrounds and<br />

goals. As an example, consider Emory Bogardus and William Carlson Smith, both<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essors <strong>of</strong> sociology at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California who became involved<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations through <strong>the</strong>ir connection with George Gleason and<br />

<strong>the</strong> YMCA <strong>of</strong> Los Angeles. Bogardus had grown up on a farm outside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> small<br />

Midwest town <strong>of</strong> Belvidere, Illinois. Upon attending college in Chicago, he had been<br />

shocked and forever changed by <strong>the</strong> progressive and cosmopolitan values which he<br />

encountered, explaining that until that time he had accepted without question <strong>the</strong> literal<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bible. The YMCA movement had affected him powerfully, and for<br />

<strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> his life Bogardus struggled to fulfil <strong>the</strong> tenets <strong>of</strong> ‘practical religion’: “I<br />

learned that real tests <strong>of</strong> religion are what one does with his religious beliefs, what <strong>the</strong>y<br />

do for one, and that daily behavior is a yardstick <strong>of</strong> what a person’s religion means to<br />

him.” He served as <strong>the</strong> Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Social Work at USC as well as <strong>the</strong> head<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sociology, and was instrumental in <strong>the</strong> Goodwill Industries <strong>of</strong> Los<br />

Angeles, which collected donated goods and sold <strong>the</strong>m to raise funds for charity<br />

work. 30 William Carlson Smith had been a teacher in Assam, India, with <strong>the</strong> American<br />

30 All information from Emory Bogardus, A <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sociology at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong><br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California (Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California Press, 1972) and his<br />

autobiography, Much Have I Learned (Los Angeles: University <strong>of</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn California<br />

Press, 1962). Quote from page 27. Bogardus’ autobiography was written during his<br />

retirement, along <strong>the</strong> narrative <strong>of</strong> a personal journey <strong>of</strong> constant learning and selfdiscovery.<br />

Curiously, he also published two autobiographical volumes <strong>of</strong><br />

Shakespearian sonnets which he had written throughout his life and travels, entitled<br />

The Traveller (1956) and The Explorer (1961).<br />

22

Baptist Foreign Mission Society before attending graduate school in sociology, and<br />

Smith’s dissertation at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Chicago was based upon his mission<br />

experiences among <strong>the</strong> Ao Naga tribe in India. 31 The ‘social gospel’ which advocated<br />

daily efforts to make <strong>the</strong> world a better place underwrote every moment <strong>of</strong> Bogardus<br />

and Smith’s work in social science. We cannot understand <strong>the</strong>ir devotion to sociology<br />

without taking into account <strong>the</strong>ir involvement in programs <strong>of</strong> personal and social<br />

improvement.<br />

The overlapping backgrounds and shared sense <strong>of</strong> social mission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Protestant ministers and <strong>the</strong> social scientists allow us to understand why <strong>the</strong> one man<br />

who did not subscribe to <strong>the</strong> vision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations as a device for social<br />

reform, Robert E. Park <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Chicago, was so insistent in his criticisms <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> missionaries who were his allies. Park, a member <strong>of</strong> Chicago’s <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Sociology and Anthropology, felt that sociology had been too closely allied with<br />

missionaries for too long, and made it a point to try and distance social science from<br />

religious organizations. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most prominent social scientists in <strong>the</strong> country at<br />

<strong>the</strong> time, Park had been chosen by Merle Davis and <strong>the</strong> Insitute <strong>of</strong> Social and Religious<br />

Research to become <strong>the</strong> Research Director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations. He brought<br />

to <strong>the</strong> survey not only a badge <strong>of</strong> scientific expertise, but a very different outlook on<br />

social science than many <strong>of</strong> his colleagues. To <strong>the</strong> eventual consternation <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> missionaries, Park was also <strong>the</strong> most influential <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey researchers.<br />

Park was not a follower <strong>of</strong> E.A. Ross and o<strong>the</strong>r sociologists who saw <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

as advocates for social reform. To him, <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> sociology was not <strong>the</strong> improvement<br />

<strong>of</strong> society, but <strong>the</strong> description <strong>of</strong> it and how it worked. Park <strong>of</strong>ten pr<strong>of</strong>essed a deep-felt<br />

distaste for <strong>the</strong> motives <strong>of</strong> ‘do-gooders:’<br />

31 William Carlson Smith Papers, UCSB Library, micr<strong>of</strong>ilmed from originals in <strong>the</strong><br />

Robert Cantwell Papers, University <strong>of</strong> Oregon Library, Special Collections.<br />

23

The first thing you have to do with a student who enters sociology is to show<br />

him that he can make a contribution if he doesn’t try to improve anybody....The<br />

trouble with our sociology in America is that it has had so much to do with<br />

churches and preachers. . . . The sociologist cannot condemn some people and<br />

praise o<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

Sociology cannot be mixed with welfare and religion. “A moral man<br />

cannot be a sociologist.” Sociology should not help to build up reform<br />

programs, but it should help those who have to build <strong>the</strong>se programs to do it<br />

more intelligently. 32<br />

Park’s stance, though it has been called conservative and fatalistic, was one which<br />

was pr<strong>of</strong>oundly anthropological. 33 Sociology was <strong>the</strong> ‘science <strong>of</strong> human behavior,’<br />

and <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> study was <strong>the</strong> mental: <strong>the</strong> ‘subjective attitudes’ which people have.<br />

The sociologist should be able to understand a social situation from <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong><br />

all its participants; moral approbation or disapproval merely blinded <strong>the</strong> sociologist to<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘inner world’ <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r people. The findings <strong>of</strong> sociology could be used by<br />

reformers to make changes, but social scientists <strong>the</strong>mselves should restrict <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

to discovering and describing what was going on. Park had been a journalist for many<br />

years before coming to sociology, and his style <strong>of</strong> empirical sociology had more to do<br />

32 Quoted from Raushenbush, Robert E. Park..., 97.<br />

33 See Fred H. Mat<strong>the</strong>ws, Quest for an American Sociology: Robert E. Park and <strong>the</strong> Chicago<br />

School (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1977), 79-189 for a discussion <strong>of</strong> later attacks<br />

on Park’s <strong>the</strong>ories. Also Paul Takagi, “The Myth <strong>of</strong> Assimilation in American Life,”<br />

Amerasia Journal 2 (Fall 1973):149-159, for an attack on Park from <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Asian American movement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1970’s.<br />

24

with empathy and description than <strong>the</strong> social prescriptions which <strong>the</strong> ministers expected<br />

from him. 34<br />

Robert Park tried very hard to distinguish <strong>the</strong> sociologists from <strong>the</strong> missionary<br />

reformers, but during <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations, <strong>the</strong> distinction was <strong>of</strong>ten hard to<br />

maintain. Without <strong>the</strong> ministers’ network <strong>of</strong> connections up and down <strong>the</strong> West Coast,<br />

<strong>the</strong> sociologists would never have been able to contact someone like Flora Belle Jan.<br />

Protestant church workers were <strong>of</strong>ten some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few ‘whites’ who had close<br />

personal contact with large numbers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chinese and Japanese on <strong>the</strong> West Coast. 35<br />

34 See Mat<strong>the</strong>ws, Quest for..., 112-115, for an introduction to <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race<br />

Relations, especially on how <strong>the</strong> survey came out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> missionary project, and a<br />

much more insightful analysis <strong>of</strong> Robert Park than that contained in Raushenbush’s<br />

biography (cited above). For an intellectual history <strong>of</strong> race and ethnicity within<br />

Chicago sociology, as well as a good discussion <strong>of</strong> what he calls <strong>the</strong> “Anglo-American<br />

Burden,” see Stow Persons, Ethnic Studies at Chicago, 1905-45 (Urbana: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Illinois Press, 1987). Person discusses <strong>the</strong> survey and <strong>the</strong> ‘ethnic cycle’ on pages 68-72.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r study <strong>of</strong> race <strong>the</strong>ory at <strong>the</strong> Chicago school is Fred Wacker, Ethnicity, Pluralism,<br />

and Race: Race Relations Theory in America Before Myrdal (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood<br />

Press, 1983), which, unfortunately, does not mention Asians or Asian Americans as<br />

<strong>the</strong> studied or <strong>the</strong> studiers. On <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> a <strong>the</strong>oretical sociology which became equated<br />

with a more ‘scientific’ approach, see John Madge, The Origins <strong>of</strong> Scientific Sociology<br />

(Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1962).<br />

35 George Gleason remarked on how he was forced to use his YMCA and church<br />

contacts to do much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research for <strong>the</strong> survey in sou<strong>the</strong>rn California because: “Dr.<br />

Bogardus’ work is largely confined to <strong>the</strong> university, and Dr. Smith’s largely to <strong>the</strong> city<br />

and <strong>the</strong> immediate vicinity.” Gleason to Davis, Sept 2, 1924 , Box 11, Papers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Survey.<br />

25

Although Jan pr<strong>of</strong>essed herself to be “quite out <strong>of</strong> sympathy with <strong>the</strong> Baptist Mission<br />

people” and “emanicipated from all religious influence,” Merle Davis was alerted to<br />

<strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> Jan through his contacts with <strong>the</strong> Fresno Baptist Mission. 36 Davis<br />

located many o<strong>the</strong>r research ‘subjects’ through his church connections.<br />

The reliance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Survey <strong>of</strong> Race Relations on <strong>the</strong> network <strong>of</strong> Protestant<br />

churches and missions on <strong>the</strong> West Coast had several important ramifications. For one,<br />

<strong>the</strong> sociologists, because <strong>the</strong>y felt <strong>the</strong>ir project was entwined and conflated with <strong>the</strong><br />

missionaries, tried to distance <strong>the</strong>mselves rhetorically from <strong>the</strong> missionary reformers.<br />

The strident tone <strong>of</strong> Park’s attempts to distinguish <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> social science from <strong>the</strong><br />