Mapping subversion

Mapping subversion

Mapping subversion

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network]<br />

On: 11 January 2009<br />

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864]<br />

Publisher Routledge<br />

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,<br />

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK<br />

Popular Music and Society<br />

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:<br />

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713689465<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>subversion</strong>:Queercore music's playful discourse of resistance<br />

D. Robert DeChaine a<br />

a<br />

Doctoral student in Cultural Studies, Claremont Graduate University,<br />

Online Publication Date: 01 December 1997<br />

To cite this Article DeChaine, D. Robert(1997)'<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>subversion</strong>:Queercore music's playful discourse of resistance',Popular Music<br />

and Society,21:4,7 — 37<br />

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03007769708591686<br />

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007769708591686<br />

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE<br />

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf<br />

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or<br />

systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or<br />

distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.<br />

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents<br />

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses<br />

should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,<br />

actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly<br />

or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion:<br />

Queercore Music's Playful Discourse of Resistance<br />

D. Robert DeChaine<br />

People have to make do with what they have ... there is a certain art<br />

of placing one's blows, a pleasure in getting around the rules of constraining<br />

space.<br />

—Michel de Certeau (18)<br />

Since the dawn of human history, social arrangements have tended<br />

to assume agonistic relations between the dominant and the subordinated.<br />

Long before terms like "culture," "folk," and "subculture" were<br />

coined, societies—guided specifically by those "on top"—were busy<br />

delineating structures of power, rule, and labor. From the ancient Egyptians<br />

to the Greeks to modern societies, one can track such cultural histories.<br />

Yet, only since the nineteenth century have scholars paid much<br />

critical attention to the ways in which culture "speaks"—that is, the<br />

ways that human social organizations define the lives and experiences of<br />

those who live them. In Culture and Anarchy, Matthew Arnold's description<br />

of culture as "the best which has been thought and said in the<br />

world" provoked a wave of early theories and critiques of culture—from<br />

Leavis's theory of mass civilization 1 to modem theories of marginality<br />

and mass culture. Meanwhile, Marx and Engels's critique of the ruling<br />

class spurred numerous critical responses to cultural forms of domination<br />

and oppression, such as those from the "Frankfurt scholars," critical<br />

theorists, and poststructuralists. Currently, there is an abundance of cultural<br />

theory and criticism from which to draw, spanning fields of sociology,<br />

cultural studies, rhetoric, and philosophy, to name a few.<br />

For modern scholars, the legacy of this rather recent turn to culture<br />

is a shared interest in understanding how marginalized groups—that is,<br />

counter- and subcultures—live both in and against the dominant culture,<br />

while at the same time maintaining some type of identities for themselves.<br />

In many ways, these "subaltern" groups lead double lives. Usually<br />

they must function in some fashion within dominant culture (one<br />

has to eat and have shelter, for instance); at the same time, their struggle<br />

becomes that of resisting forces of control which threaten to silence their<br />

7.

8 • Popular Music and Society<br />

values, attitudes, and beliefs. Such subaltern groups traverse lines of<br />

race, religion, gender, sexual preference, and even artistic expression,<br />

often challenging or shattering those lines in the process. That there are<br />

so many such groups in existence attests to the vibrancy of their discourses.<br />

My intention in this discussion is not to make a particular case for<br />

this or that group. Rather, I wish to suggest that by tracing discursive<br />

formations of subaltern groups—borrowing from Grossberg's terminology,<br />

by mapping "sensibilities"—one can uncover tactical choices which<br />

bring to light a subaltern group's motives. Following Grossberg, a "sensibility"<br />

signifies a subculture's dominant organization of effects, and it<br />

describes the various intersections or "articulations" of actions which<br />

account for that organization. This is not to say, however, that all actions<br />

are intentional in a particular subculture, nor that they are all neatly<br />

ordered or even "sensible." Discursive sensibilities are not monolithic<br />

structures—rather, they signify groupings of overlapping and interrelated<br />

possibilities for responding to situations. In this way, discursive<br />

sensibilities represent ever-shifting networks of time- and history-bound<br />

effects. By analyzing discourse in terms of sensibilities, one can not only<br />

chart particular group actions, but also tendencies, trajectories, and problematic<br />

implications of those actions.<br />

Specifically, I intend to explore one particular aesthetic discourse—<br />

the "queercore" musical movement—in order to attempt to uncover a<br />

"sensibility of play" which grounds its actions. Queercore above all represents<br />

a confluence of punk rock music and queer politics, although<br />

such a description oversimplifies the relationship. Queercore music<br />

exhibits many of punk rock's reactions to a rock formation now perceived<br />

as bloated and hopelessly corporate. The music is fast, loud, and<br />

often quite raw in form and production; a "do it yourself ethic often<br />

guides artistic and business choices. Queercore lyrics are often sexually<br />

explicit and, by popular standards, vulgar. They can be comic and playful,<br />

although some deal with serious themes as well. Queercore artists<br />

are ultimately political, since they often express a cultural "lifestyle" that<br />

rubs up against mainstream social norms. Queercore performances stress<br />

interaction; while they sometimes spectacularize and mock conventional<br />

rock stage behaviors, they also encourage spectators to "stage dive" and<br />

physically participate in the performance.<br />

These features of queercore allow the artists to share a kind of cultural<br />

identity or solidarity with their fans. While identity politics certainly<br />

plays an important role in their attitudes and behaviors, I am<br />

specifically interested in the signifying play which undergirds the discourse.<br />

Play endows queercore participants with a space in which to

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 9<br />

resist and subvert the materials of the dominant culture. It is a way of<br />

appropriating and turning against—of working within the system in<br />

order to sabotage and undermine the cultural values which it holds up as<br />

normative and "correct." A sensibility of play enables queercore participants<br />

the "semiotic guerrilla warfare" which Eco (103-24) speaks of; it<br />

signifies a "way of making" (de Certeau), a politics of the everyday<br />

which deconstructs (or at least problematizes) the inside/outside binary.<br />

Above all, play empowers. It offers for its participants a liberation, however<br />

temporary, from the ideological oppression of the dominant culture.<br />

Robert Walser argues this point in his discussion of signifying play with<br />

regard to heavy metal and gender politics:<br />

There is nothing superficial about such play; fans and musicians do their most<br />

important "identity work" when they participate in the formations of gender and<br />

power that constitute heavy metal. Metal is a fantastic genre, but it is one in<br />

which real social needs and desires are addressed and temporarily resolved in<br />

unreal ways. These unreal solutions are attractive and effective precisely<br />

because they seem to step outside the normal social categories that construct the<br />

conflicts in the first place. (133-34)<br />

Play in queercore functions in much the same capacity. Though queercore<br />

may ultimately aspire to "mere aesthetics," its ludic politics stress<br />

its symbolic defiance; thus, a playful sensibility can wage a powerful<br />

assault on "serious" cultural normativity.<br />

A variety of starting points and openings for this study are provided<br />

by the current breadth of scholarship in popular music and popular culture.<br />

For instance, one of the immediate difficulties of exploring connections<br />

between queer and punk discourses is the traditionally silent/<br />

silenced history of homosexuality in modern music. In his book Queer<br />

Noises, John Gill begins to trace such a history as a perpetuated "code of<br />

silence" controlled by the cultural elite, enforced by the music industry<br />

and ultimately manifested as a fear of public disclosure. Gill argues that<br />

traces of queerness have been evident in queer artists' music and in their<br />

often ambiguous lyrics. Queer listeners have always known this and<br />

have, as has Gill himself, reveled in the discovery of such "queer<br />

noises." Other scholars have come to similar conclusions. McClary has<br />

noted the academic impoverishment of studies linking music to issues of<br />

sexuality and gender, noting that it "is an intimidating task to try to<br />

unlock a medium that has been so securely sequestered for so long" (20).<br />

Her work uncovers a variety of musical, musicological, and power relations<br />

which have occluded one another throughout the twentieth century.<br />

Scholars have also traditionally ignored questions regarding music's dis-

10 • Popular Music and Society<br />

cursive inscriptions. With rare exception—Dave Laing's discourse on<br />

punk rock 2 and Dick Hebdige's Subculture: The Meaning of Style immediately<br />

come to mind—scholars have only recently turned their attention<br />

toward this significant dimension of culture. Pioneering work by Cagle<br />

and Walser and the collection of essays in the book Queering the Pitch<br />

(Brett, Wood, and Thomas) point toward new and important directions in<br />

popular music studies. Even so, recent scholarship continues to mark<br />

queer absences. For example, in The Sex Revolts Reynolds and Press<br />

devote nearly 400 pages to "a kind of psychoanalysis of rebellion" (xiv)<br />

in rock music; one wonders where, in all of their analysis of male and<br />

female strategies of rebellion, any space for queer discourse could even<br />

exist. Such absences call for continued attention to the "queer noises"<br />

that contribute to the discourse of popular culture.<br />

Several recent studies have argued for regarding popular music as<br />

dialogic, an argument which the present study aims to further advance.<br />

Lipsitz, for example, relates the "dialogic criticism" of Russian literary<br />

theorist and critic Mikhail Bakhtin to explain how popular music functions<br />

historically: "[P]opular music is nothing if not dialogic, the product<br />

of an ongoing historical conversation in which no one has the first or last<br />

word" (99). Lipsitz goes on to relate Bakhtin's notion of popular carnival<br />

traditions and their "polysémie" forms of representation, forms which he<br />

argues pervade the discourse of popular music. Lipsitz's dialogic critical<br />

approach allows for a reflexive view of culture as it avoids the trappings<br />

of formalism and essentialism. Shank, in his study of the Austin, Texas,<br />

music scene, also draws upon Bakhtin to further elucidate the temporality<br />

and polysemy of popular music in his description of the honky-tonk as a<br />

site for the prolongation and perpetuation of the liminality of the carnival<br />

scene. He argues that honky-tonks "were magical places where promises<br />

were made and new possibilities of life could be imagined in the free<br />

recombination of repressed elements of the human" (35). In much the<br />

same sense, I will argue, queercore participants imagine a liminal space<br />

in which such "repressed elements" are "played out" in carnivalesque<br />

ways. The work of scholars such as those noted above constitutes many<br />

of the trajectories of thought from which this study draws.<br />

In this discussion I wish, then, to ground the queercore discourse in<br />

a sensibility of play. First I consider play's carnivalesque atmosphere,<br />

elucidated by Bakhtin, as I argue that carnival signifies the space in<br />

which play circulates. From and within the playful sensibility, particular<br />

tactical operations will be seen to derive—namely, parody, pastiche, and<br />

bricolage. I next identify particular musical, lyrical, and performative<br />

examples of these playful tactics which exist specifically in the queercore<br />

discourse. In my subsequent analysis, I examine the music of the

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 11<br />

group Pansy Division, considered by many to be the foremost representatives<br />

of queercore. In analyzing Pansy Division's music, lyrics, and<br />

live performances, and personal narratives by band members, I intend to<br />

bring to light a sensibility of play in practice. Finally, I consider the<br />

implications of treating sensibilities as sites for discursive analysis, and<br />

draw some conclusions regarding the efficacy of play for queercore participants.<br />

In all, I hope to bring to light in the queercore discourse a<br />

sense of what Lipsitz eloquently captures in his discussion of postmodernism<br />

and popular music in ethnic minority cultures:<br />

Postmodern culture places ethnic minorities in an important role. Their exclusion<br />

from political power and cultural recognition has allowed aggrieved populations<br />

to cultivate sophisticated capacities for ambiguity, juxtaposition, and<br />

irony—all key qualities in the postmodern aesthetic. The imperatives of adapting<br />

to dominant cultures while not being allowed full entry into them leads to<br />

complex and creative cultural negotiations that foreground marginal and alienated<br />

states of consciousness. Unable to experience either simple assimilation or<br />

complete separation from dominant groups, ethnic cultures accustom themselves<br />

to a bifocality reflective of both the ways that they view themselves and<br />

the ways that they are viewed by others. (135)<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> a Sensibility of Play<br />

The queercore movement, as I have suggested, signifies intersections<br />

between two complex and highly developed discursive formations.<br />

More importantly, though, queercore describes a sensibility, that is, it<br />

articulates specific conditions in which the postmodern aesthetics of<br />

punk rock and the anti/identity dynamics of a queer politics give rise to<br />

a subversive and potentially liberatory "emergent" discourse. In attempting<br />

to locate this space, I shall map a "sensibility of play" which will be<br />

shown to derive from a carnivalesque view of culture. "Carnival," as<br />

elucidated by Bakhtin, describes conditions in which social and cultural<br />

hierarchies are inverted and/or debased, if only temporarily. Within such<br />

a carnival atmosphere, I will argue, particular resources are made available<br />

to participating subaltern groups, which they may in turn employ<br />

tactically to subvert forces of ideological oppression wielded by the<br />

dominant (mainstream) culture. Such tactics of resistance define a ludic<br />

politics—a playful yet tactical response to perceived conditions of<br />

oppression. By mapping out a sensibility of play, then, my intention is to<br />

ground subaltern discursive tactics such as those of the queercore movement<br />

in a practical theoretical matrix.<br />

I want to begin by tracing a dominant organization of a particular<br />

series of effects which operate in a given culture—what Grossberg terms

12 • Popular Music and Society<br />

a "sensibility" 3 —and grounding it in a discourse of signifying play. Recognizing<br />

that "play" carries a number of connotative meanings, my<br />

intention is to consider ways in which play can function tactically. Johan<br />

Huizinga's pathbreaking study of play and its bearing on culture provides<br />

a profitable starting point. Huizinga argues that play is one of the<br />

most fundamental characteristics of the human condition; indeed, he<br />

argues that "civilization arises and unfolds in and as play" (ix). Huizinga<br />

attempts to define some of play's formal characteristics thus: "play is a<br />

voluntary activity or occupation executed within certain fixed limits of<br />

time and place, according to rules freely accepted but absolutely binding,<br />

having its aim in itself and accompanied by a feeling of tension, joy and<br />

the consciousness that it is 'different' from 'ordinary life'" (28).<br />

Huizinga's definition, though problematic on some accounts, 4 highlights<br />

the significance of rules and "fixed limits," of tactical moves and negotiations<br />

and an omnipresent consciousness of difference. Other studies,<br />

such as in the work of John Fiske, have described playful tactics as<br />

rooted in orientations either of evasion or resistance. 5 Still others have<br />

situated signifying play as a postmodern strategy (Manuel) or as "disruptive"<br />

or "troublesome" performative acts (Butler, Gender Trouble;<br />

Berube and Escoffier; Hennessy). Rather than conflating or delineating<br />

definitions, or attempting to derive an embodied "meaning" for play, I<br />

wish at this point to examine the specific conditions in which play surfaces<br />

for particular subaltern groups as a strategy for locating gaps in the<br />

cultural fabric, and to specify ways in which play offers the possibility to<br />

step outside of the traditional, oppressive power structure. In light of<br />

such an objective, the following discussion considers Mikhail Bakhtin's<br />

concept of the camivalesque as a theoretical ground for an understanding<br />

of subaltern discursive practices and the social conditions in which they<br />

are given rise.<br />

Conditions for Play: Bakhtin and the Carnival Scene<br />

Bakhtin's notion of the carnival, originally worked out in his 1940<br />

thesis and elucidated in his book Rabelais and his World, has been recurrently<br />

studied in theoretical and critical scholarship (Stamm; Thompson;<br />

Clark and Holquist; Stallybrass and White). Bakhtin, a literary critic,<br />

compares Rabelais's treatment of the novel to the medieval carnival,<br />

arguing that particular "camivalesque" features allow Rabelais to endow<br />

the novelic hero with an open generic quality, and an openness to the<br />

dialogue between author and hero (Morris). These camivalesque features<br />

include: an inversion of social hierarchies and structures of power; an<br />

emphasis on bodily excesses and pleasures; comic debasements and parodie<br />

treatment of particular scapegoated individuals; uses of profanity,

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 13<br />

vulgarity, and degradation; and a generally festive atmosphere of spectacle<br />

and laughter. All of these "forms of protocol and ritual based on<br />

laughter and consecrated by tradition" (Bakhtin 5) served to offer:<br />

a completely different, nonofficial, extraecclesiastical and extrapolitical aspect<br />

of the world, of man, and of human relations; they built a second world and a<br />

second life outside officialdom, a world in which all medieval people participated<br />

more or less, in which they lived during a given time of the year. (6)<br />

Carnival in Bakhtin's view thus represented another reality, one in which<br />

the oppressions of the everyday were flip-flopped, and within which was<br />

provided a potential escape from one's inhibitions, one's socially<br />

imposed standards of normalcy, at least temporarily.<br />

Yet, at the same time that carnival offered an escape from societal<br />

norms of behavior, it was also sanctioned by those in power. It was<br />

regarded as a kind of cultural pressure valve—a way of regulating normativity<br />

by allowing it to periodically run loose in a ritual form. As<br />

such, persons in power often participated in the rituals, allowing themselves<br />

to be subjected to scapegoating and other acts of ridicule: "Carnival<br />

is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone<br />

participates because its very idea embraces all the people" (Bakhtin 7).<br />

Carnival rituals stressed laughter, a focus on sensual pleasures and a<br />

"strong element of play" (Bakhtin 7); thus, the Clown and the Fool were<br />

often celebrated as comic characters. Moreover, carnival laughter signifies<br />

an essential difference from modern satire:<br />

The satirist whose laughter is negative places himself above the object of his<br />

mockery, he is opposed to it. The wholeness of the world's comic aspect is<br />

destroyed, and that which appears comic becomes a private reaction. The<br />

people's ambivalent laughter, on the other hand, expresses the point of view of<br />

the whole world; he who is laughing also belongs to it. (12)<br />

As political, hierarchical, and ecclesiastical distinctions were dissolved,<br />

all were welcome to participate in the laughter. "In fact, carnival does<br />

not know footlights, in the sense that it does not acknowledge any distinction<br />

between actors and spectators" (Bakhtin 7).<br />

The result of this dissolution of space between actors and spectators<br />

was an emphasis on physical contact and physical excess, evidenced in a<br />

host of bodily inscriptions. Carnival politics as such were politics of the<br />

body, temporarily emptied of privilege beyond immediate meanings and<br />

pleasures. Bodies were displayed in all their excessive vulgarity;<br />

medieval carnival emphasized a "grotesque realism" (Bakhtin 18) in an

14 • Popular Music and Society<br />

extreme exaggeration of the "normal" bodily image. Vulgarity was also a<br />

prominent feature of carnival language and discourse. Profanities and<br />

abusive language, used in "isolation from context and intrinsic character"<br />

(Bakhtin 17), was prevalent; that is, language was emptied of its traditional<br />

relevance and meaning. It was a language of surfaces, of<br />

exaggerated tone and graphic offensiveness. Bakhtin argues that since "a<br />

new type of communication always creates new forms of speech or a<br />

new meaning given to the old forms," profane and abusive language created<br />

for participants of the carnival a "new type of carnival familiarity"<br />

(16), one in which meaning and, particularly, sincerity was made mockery.<br />

Within the carnival atmosphere profane language thus "acquired the<br />

nature of laughter and became ambivalent" (17). Finally, Bakhtin<br />

stresses such carnival ambivalence as endowing the participant with an<br />

open, incomplete subjectivity. He points out that in Rabelais's depictions<br />

of bodily and linguistic excess, "the grotesque images preserve their<br />

peculiar nature, entirely different from ready-made, completed being"<br />

(25), defying "classic" aesthetic sensibilities. Thus, one's image, behavior,<br />

and actions were open, undecidable, never complete.<br />

These five characteristics—the participatory status of subjects, the<br />

spectacularizing of ritual, the emphasis on the body and bodily excesses,<br />

the milieu of laughter and mockery of the conventional, and the openendedness<br />

of the subject—signify, then, both the actions and behaviors of<br />

the participants, and describe the conditions which bring about the scene<br />

of the carnivalesque. It is an atmosphere at once disconnected from the<br />

normal, the traditional, the "proper," but at the same time interwoven<br />

with and entirely dependent upon the larger sociocultural structure. It<br />

inverts, reorients, parodies, and debunks traditional sensibilities, even as<br />

its "players" recognize their roles in the "game." It reorganizes power<br />

both temporally and spatially, even as its spectacles offer only fleeting<br />

and temporary reconfigurations. It is at once aesthetic and base, political<br />

and depoliticized, structured and "wild." It is offensive, vulgar, and abusive,<br />

and its discourse resists depth and meaning. It signifies resistance to<br />

dominance, yet recognizes its own complicity in the game. It allows for<br />

both <strong>subversion</strong> and evasion, and invests its participants with a self-consciousness<br />

of their conditions and their actions. Ultimately, carnival signifies<br />

"a gap in the fabric of society . . . [SJince the dominant ideology<br />

seeks to author the social order as a unified text, fixed, complete, and forever,<br />

carnival is a threat" (Clark and Holquist 301).<br />

Tactics of Play<br />

A discourse grounded in a carnivalesque, playful sensibility provides<br />

the subaltern participant opportunities for various tactical deploy-

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 15<br />

ments. These moves, which I will term "tactics of play," signify the practical<br />

"tools" for a playful subculture. Within the purview of subcultural<br />

and postmodern theory, much work has been done to identify and elucidate<br />

tactics of resistance and <strong>subversion</strong>. In this section I wish to highlight<br />

four particular terms which will prove vital to this discussion:<br />

appropriation, parody, pastiche, and bricolage. The functional variations<br />

which these terms embody characterize a discourse operating within a<br />

sensibility of play. An understanding of how these four strategies inform<br />

a ludic politics will make clear the political implications of a playful aesthetic.<br />

Hebdige's study of subculture provides an insightful view of how<br />

appropriation becomes a strategic operation. He posits subcultures such<br />

as punk rockers as complex subordinate groups whose discourses often<br />

manifest themselves in their stylistic codes. Within such codes, struggles<br />

over symbols, both material and verbal, serve as a primary agency for<br />

signification and identity. Expanding upon Hall and Jefferson's study of<br />

youth subcultures in postwar Britain, Hebdige describes a process in<br />

which seemingly insignificant objects can be appropriated by a subculture<br />

in order to ideologically reverse or reorder existing meanings. This<br />

"double inflection" of illegitimating, while at the same time legitimating,<br />

uses and use values serves a subversive function: "These 'humble<br />

objects' can be magically appropriated; 'stolen' by subordinate groups<br />

and made to carry 'secret' meanings: meanings which express, in code, a<br />

form of resistance to the order which guarantees their continued subordination"<br />

(18). In the punk subculture, an object such as a safety pin<br />

becomes a statement of fashion, but also one of defiance; it symbolizes a<br />

transformation of what was once an object used to repair clothing, for<br />

instance, into a tool for self-mutilation. The object's (re)significance is<br />

thus ascribed by its appropriation, but also gauged by the reaction it generates<br />

from those against whom its use is directed.<br />

As symbols can be appropriated and stripped of their original meaning<br />

and significance by subcultural groups, so there are different modes<br />

of re/signification. Three important and related elements in this process<br />

merit discussion. The first, parody, operates in more or less a straightforward<br />

and linear manner. Parody marks the presence of carnival laughter:<br />

it pokes fun, it mocks the original meaning, but in a way such that its<br />

motives and devices are plain, recognizable to those it mocks. In parody,<br />

therefore, the form remains relatively stable with regard to the original<br />

form it parodies. The joke may be vicious, it may be subversive, but it is<br />

always recognized as such by the subject of the parody: "So there<br />

remains somewhere behind all parody the feeling that there is a linguistic<br />

norm" (Jameson, "Postmodernism and" 113-14).

16 • Popular Music and Society<br />

Pastiche, on the other hand, performs quite a different operation. In<br />

his seminal discussion of postmodernity, Jameson has described pastiche<br />

as a "blanking" of parody, a marker of an oncoming postmodernity:<br />

Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar mask, speech in a dead language:<br />

but it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without any of parody's ulterior<br />

motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any<br />

conviction that alongside the abnormal tongue you have momentarily borrowed,<br />

some healthy linguistic normality still exists. ("Postmodernism, or" 65)<br />

This distinction between parody and pastiche illustrates well the way in<br />

which contemporary forms of aesthetic communication, for example,<br />

still operating within "modernist" frames of irony and satire, often dare<br />

to fracture themselves across their own lines. Artists working within various<br />

forms of postmodern and avant-garde art employ a "cut and paste"<br />

pastiche technique in order to disrupt linearity and "completeness."<br />

Modern dancers and performance artists incorporate moves which disorganize<br />

and reorganize traditional performance styles. New journalism,<br />

postmodern literature, and poststructuralist criticism use pastiche to<br />

undercut modernist literary forms. Much avant-garde music, including<br />

rap, hip-hop, and punk, also employs techniques of pastiche, enabled by<br />

time- and space-altering instruments such as tape loops and the sampling<br />

machine. Scholars such as Beadle have argued that the incorporation of<br />

the sampler in pop music indeed signals its postmodern character.<br />

Another useful term is bricolage, which describes the process by<br />

which objects and musical forms are appropriated and reconstructed in<br />

punk. Following Levi-Strauss's characterization of bricolage as a "science<br />

of the concrete," Hebdige characterizes subcultures such as the<br />

mods and the punks as engaging in such actions, insofar as they "appropriated<br />

another range of commodities by placing them in a symbolic<br />

ensemble which served to erase or subvert their original straight meanings"<br />

(104). Hebdige goes on to evoke Eco's "semiotic guerrilla warfare"<br />

in reference to the subaltern fashion ensemble, which he describes<br />

as stripped of meaning and fetishized (105). Another example of bricolage<br />

can be seen in punk's incorporation of diverse stylistic musical<br />

forms such as reggae, industrial, and electronic music. Punk in its parodie<br />

frame often mocks and playfully mimics other musical genres; many<br />

punk groups use both parody and pastiche in their music, lyrics, and artwork,<br />

epitomizing a bricolage of form and genre. These three stylistic<br />

elements—parody, pastiche, and bricolage—together with the appropriation<br />

and excorporation of symbols in order to reposition semiotic control,<br />

thus signify playful tactics of resistance.

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 17<br />

Thus far I have examined the carnival conditions and the resultant<br />

tactical operations which signify a playful sensibility operating at once<br />

against and within mainstream cultural politics. This condition of<br />

(re)acting both within and without the cultural mainstream presents tensions<br />

which both empower and limit participants. In the section that follows,<br />

I situate the queercore musical movement as a site in which a<br />

sensibility of play can be seen to operate. Queercore brings many significant<br />

and unique social and aesthetic dynamics to the fore. I hope to<br />

demonstrate how such factors can contribute to a better understanding of<br />

subculture as a site of constant struggle, and how such struggle rubs up<br />

against the temporal strategies of play. Thus, a thorough examination of<br />

queercore music, and specifically of the group Pansy Division, will highlight<br />

particular questions which a sensibility of play must ultimately confront.<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> Queercore<br />

In the simplest of terms, queercore music might best be thought of<br />

as a queer(ed) punk rock. However, as one begins to peel back its layers,<br />

queercore equally demonstrates a queer identity politics with punk rock<br />

as its vehicle. In this section I examine each of these angles and follow<br />

out their trajectories in an effort to arrive at some understanding, at the<br />

least, of what a queercore discourse would look like from a critical vantage<br />

point. By highlighting some important dynamics which queer<br />

theory and queer identity bring to bear, I want to suggest that queercore<br />

represents a self-reflexive subculture which grounds its identity in a politics<br />

of difference, and which, through its playful tactics, enlists punk<br />

rock as its mode of communication. I first provide a general history of<br />

queercore which will foreground the discussion. Next I briefly sketch<br />

out some features of punk rock which signify queercore's aesthetic sensibility.<br />

I then demonstrate how issues of queer identity provide tactical<br />

points of intersection with punk, points which tear open a space for<br />

queers to rant a playful yet political resistance. <strong>Mapping</strong> a general terrain<br />

for queercore will allow for an analysis which takes into account not<br />

only its music and lyrical manifestations but also its larger discursive<br />

formation—its playful sensibility.<br />

A Brief History of Queercore<br />

The term "queercore," as I have suggested, describes a musical subformation<br />

which combines much of the aesthetic of punk rock music<br />

with radicalized perspectives on gay and lesbian politics and identity. It<br />

has been described in the media as "radical" and "in your face" (Sullivan<br />

9), explicit and amusing (Kot). At the same time, persons who align

Iß • Popular Music and Society<br />

themselves with the term are less apt to categorize its parameters. As<br />

Matt Wobensmith, editor of Outpunk, a queercore '"zine," has suggested:<br />

"I can't tell you what it means, because I don't know, and ultimately<br />

the definition starts with you. What do you want it to be? What<br />

do you want out of life? Please don't let what you see and hear be your<br />

only defining tools" (8). Wobensmith thus suggests that queercore participants<br />

take it upon themselves to "make" the discourse into something<br />

which has direct bearing upon their lives, rather than be limited by<br />

imposed labels and boundaries. This difference between the ways in<br />

which the (mainstream) media describe queercore and how queercore<br />

participants describe themselves highlights a significant tension. It<br />

shows an outward tendency to encapsulate and categorize a "movement,"<br />

and an internal struggle to define an inclusive and noncategorical<br />

identity marker. This tension signifies a major thematic marker which<br />

plays out in punk aesthetics and queer identity, the subjects of the following<br />

sections. It also sets the stage for queercore's playful sensibility<br />

and tactics which characterize the discourse.<br />

As a musical "movement," queercore can be traced back to the mideighties.<br />

Bruce LaBruce, a gay man who also happened to enjoy punk<br />

rock, felt disenfranchised by both scenes in his city of Toronto. He felt<br />

that the two movements had much in common as potentially empowering<br />

voices, so he launched JD's, a magazine which he dubbed "homocore."<br />

As his movement grew, LaBruce eventually released Homocore<br />

Hit Parade, a recorded collection of queer punk artists from Canada and<br />

America (Sullivan 9). Over the next few years, queercore continued to<br />

grow in popularity and media exposure, with dozens of new bands and<br />

hundreds of amateur 'zines emerging. In 1994, the Outpunk record label,<br />

headed by 'zine editor Wobensmith, released Outpunk Dance Party, "an<br />

eleven band queer punk compilation" which highlighted many of the<br />

premier queercore artists. These include Pansy Division, Tribe 8, Sister<br />

George, and the Mukilteo Fairies. Also in 1994, Pansy Division was<br />

asked to support Green Day, a popular punk rock band, on a worldwide<br />

tour. This exposed them to a massively expanded audience of both<br />

straights and queers and heightened queercore's media exposure. At present,<br />

queercore continues to attract a growing and more diverse audience<br />

of participants, both solidifying the discourse as a movement and heightening<br />

the participants' struggle against mainstream co-optation. I now<br />

turn to an examination of how this internal struggle is negotiated in and<br />

through the aesthetics of punk rock and through issues of queer politics<br />

and identity.

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 19<br />

An Aesthetic of Punk Rock<br />

As mentioned earlier, the queercore discourse is fashioned from two<br />

primary wellsprings of ideological resistance: punk rock music and radical<br />

gay politics. Queercore as a musical form takes as its primary inspiration<br />

a path blazed by a second wave of punks, emerging in response to<br />

the "alternative" rock of the 1980s. These new punks decry what they<br />

view as the corporate tainting and co-optation of punk and call for a<br />

return to a more localized, independent grassroots movement. Aligned<br />

with the "new" punk, queercore music favors an ethic of raw, "do it<br />

yourself performance and production hearkening to the original punk<br />

rock sound of the late 1970s. In addition to its fiercely anticorporate<br />

musical attitude, queercore borrows from punk's artistic forms of <strong>subversion</strong>.<br />

Henry compares punk rock to avant-garde art, citing similarities<br />

between punk and earlier twentieth-century artistic movements such as<br />

futurism, surrealism, and dadaism in their "unusual fashions, the blurring<br />

of boundaries between art and everyday life, juxtapositions of seemingly<br />

disparate objects and behaviors, intentional provocation of the audience,<br />

use of untrained artists or transcendence of technical expertise, and drastic<br />

reorganization (or disorganization) of accepted performative styles<br />

and procedures" (30). These hallmarks of punk can be said to describe<br />

much of queercore's musical discourse as well. Indeed, queercore is considered<br />

by many to be, at least musically, an offshoot of early punk<br />

rock—although such a description will be shown to be problematic.<br />

Following the cue of punk rock's raw <strong>subversion</strong> of conventional,<br />

"straight" rock, production values are often subverted in queercore<br />

recordings as well. In contrast to the slick commercial production prevalent<br />

in much rock music, queercore production celebrates a "do it yourself<br />

attitude meant to capture or emulate a live performance. Frith's<br />

claim that "punk demystified the production process itself—its message<br />

was that anyone could do it" (159) is readily applicable to queercore. As<br />

with punk, queercore often revels in its defects, its intentional "mistakes"<br />

which designate it as angry, emotional, frustrated, and, above all,<br />

authentic. Gow has posited a "pseudo-reflexive" strategy in the production<br />

of alternative music videos, in which some, but not all, aspects of<br />

the production process are deliberately "left in" the production, bolstering<br />

credibility and authenticity. These same aspects can be seen at work<br />

in punk and queercore records, in the form of "studio chatter," noises of<br />

strings breaking, and the trademark cry of "one, two, three, four!" which<br />

precedes some of the songs. In sum, queercore can be said to share many<br />

of (early) punk rock's aesthetic sensibilities. Its anticorporate, antiproduction<br />

attitude positions it as a voice of musical <strong>subversion</strong> in relation<br />

to commercial popular music.

20 • Popular Music and Society<br />

Queercore and Queer (Anti)identity<br />

As much as queercore resonates with the punk rock aesthetic, it is<br />

also informed by issues of queer identity and the tensions which a queer<br />

politics brings to traditional lesbian and gay subjectivities. Queercore is<br />

not just about the music—it is about the lives and values of the people<br />

who participate in it. First and foremost, being queer (or calling oneself a<br />

queer) signals a conscious move away from totalizing concepts of<br />

gender and sexuality. Sedgwick suggests that queerness can connote "the<br />

open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances,<br />

lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of<br />

anyone's gender, of anyone's sexuality aren't made (or can't be made) to<br />

signify monolithically" (8). In this conception, Sedgwick leaves open the<br />

prospect of an inclusive yet open category: an epistemological move<br />

away from oppositional binaries in which Western societies have<br />

become locked. Penn, alluding to the oppressive tendency to totalize categories<br />

like sexuality and normality, argues that queers "aim to destabilize<br />

the boundaries that divide the normal from the deviant and to<br />

organize against heteronormativity" (31). She also cites an aesthetic and<br />

political motive of queers to defy assimilation into the sociocultural<br />

mainstream, a traditional pursuit of many lesbian and gay individuals<br />

and groups. Pointing to Berube and Escoffier's claim that "queer" refers<br />

to a more confrontational challenge and the embracing of categories of<br />

the marginalized and the disempowered, Penn underlines both the antiassimilationist<br />

strategic aims and the embracing and valuing of difference<br />

which characterize a queer politics and aesthetics.<br />

These anti/categorical features of queerness, however, present a<br />

problematic view of the concept of categories themselves. That is, by<br />

assigning a category of "queer," the term seems to impose the very limitations<br />

it would seek to diminish. As Butler points out:<br />

As much as identity terms must be used, as much as "outness" is to be affirmed,<br />

these same notions must become subject to a critique of the exclusionary operations<br />

of their own production: For whom is outness a historically available and<br />

affordable option? Is there an unmarked class character to the demand for universal<br />

"outness"? (Bodies 277)<br />

Butler's problem is not with outness or queerness; rather, it lies in the<br />

totalizing and exclusionary implications inherent in the terms themselves.<br />

As a response to such categorical tyranny, Sedgwick argues that<br />

"queer" signifies not so much a category as a collection of "performative<br />

acts of experimental self-perception and filiation" (9), highlighting a<br />

processual radicalization and contestation of traditional, empirical cate-

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 21<br />

gorfes like "lesbian" or "gay." Sedgwick's attention to the performative<br />

aspects of queerness also stresses the individual, self-perceptive, and<br />

self-reflexive aspects of being queer. Queer identity is thus both<br />

reflected in individual pursuit of self-identity and problematized by constraints<br />

which a queer category may implicitly or explicitly embody.<br />

Queers, and specifically queer activist groups, attempt to explode<br />

what they view as oppressive social normativities by exposing or transgressing<br />

the binary divisions of the categories upon which they rest. This<br />

deconstructive impulse is seen in Sedgwick's argument, and is evidenced<br />

throughout much of queer theory and scholarship. There remains, however,<br />

a tension if not a contradiction between functions of power and<br />

one's social identity, be it individual or collective. By naming oneself as<br />

"queer," one strives for self-perception—an identity—yet at the same<br />

time resists a totalizing concept of what that perception would entail. In<br />

thwarting the oppressive forces of social (heteronormative) power, one<br />

attempts to regain control, yet that control—that power—is never fixed.<br />

By celebrating difference, in other words, the category of queer seems to<br />

be at odds with itself.<br />

Struggles over issues of identity politics—that is, struggles over<br />

what exactly can/must constitute an identity—lead some scholars to<br />

envision or theorize a lesbian, gay, or queer postidentity politics based<br />

upon difference (Patton; De Lauretis; Seidman, "Identity and Politics";<br />

Slagle) rather than essences. Slagle, for example, cites the queer activist<br />

group Queer Nation as largely transcending the confínes of identity politics<br />

and essentialist exclusionary practices by instead focusing their<br />

efforts on difference, thus subverting "the dominant structure by refusing<br />

to use its terms" (93). Others, such as Bersani, call for a kind of "gay<br />

specificity," which would signify "an anticommunal mode of connectedness<br />

we might all share, or a new way of coming together" (10). Such a<br />

specificity would denounce sexual preference as the sole criterion for<br />

sexual identity; rather, it would encourage the ways in which we might<br />

theorize past categories like identity and difference and instead focus on<br />

an ever-shifting "we," or, in Bersani's words, toward an "adventure in<br />

bringing out, and celebrating, 'the homo' in all of us" (10). Seidman suggests<br />

that queer interventions signify a shift toward a "cultural politics of<br />

knowledge" ("Deconstructing" 128) in which queer critics must be willing<br />

to lay out an ethical foundation for its postidentity if it is to effectively<br />

subvert notions of identity and difference. What seems clear in the<br />

demands of queer theory and queer politics is a shift away from identity<br />

itself toward a less confining and more open social empowerment.<br />

Whether by confrontational acts or strategies of visibility, or in the theoretical<br />

call by Fuss for a "politics of cultural <strong>subversion</strong>" (qtd. in Seid-

.22 • Popular Music and Society<br />

man, "Deconstructing" 131), issues raised by queer theorists are evidenced<br />

in the (anti)identity politics and subversive practices of activist<br />

groups like Queer Nation and ACT-UP, demonstrating a pragmatic cultural<br />

relevance in the everyday lives of queers.<br />

These focuses of queer theory and identity politics—of deconstructing<br />

oppositional binaries and social categories of gender, sexuality, and<br />

heteronormativity; and of undercutting identity politics by instead focusing<br />

on the permeability and openings allowed by difference—underpin<br />

the strategies of <strong>subversion</strong> and resistance which queers employ in their<br />

everyday lives. These "postmodern" discursive practices—appropriation,<br />

camp, genderfuck, visibility actions, and signifying play—<br />

empower queers in a forum which, at least ideally, avoids the trappings<br />

of embodied identity and instead promotes an inclusive, empowering<br />

voice of resistance. Queercore takes many of these foci as starting points<br />

for political and aesthetic <strong>subversion</strong> against both heteronormativity and<br />

musico-normativity. Therefore, these musicians rebel on two separate<br />

though related fronts, since homosexuality has traditionally been a silent<br />

(and silenced) force in both mainstream music and in punk rock.<br />

I have attempted to foreground an argument that queercore is more<br />

than simply punk rock which happens to be performed by queers. A<br />

recent San Francisco Chronicle article defines queercore as a term<br />

describing "punk rock bands formed by gays and lesbians whose politically<br />

charged music explores aspects of being gay with a defiant mixture<br />

of humor and anger" (Gina Arnold 25). Though I agree with this description<br />

generally, I hope to have underscored the point that queer issues are<br />

not limited to categories of sexuality and sexual preference, and that<br />

"anger" and "humor" are but discursive tactics "played out," as it were,<br />

yet anchored in real issues which impact the lives of human beings. An<br />

analysis of the music of Pansy Division, one of queercore's foremost<br />

groups, will demonstrate how a playful sensibility grounds queercore's<br />

tactical <strong>subversion</strong> and resistance to dominant and oppressive mainstream<br />

ideologies. In the analysis, I also intend to demonstrate some of<br />

the inherent tensions of a playful strategy—that the struggle for identity<br />

from within a playful discourse problematizes an outward political<br />

impact.<br />

A Sensibility of Play in the Music of Pansy Division<br />

Although it is problematic to attempt to "symbolize" queercore in<br />

one particular band, the San Francisco-based group Pansy Division signifies<br />

many of queercore's most prominent discursive features. First, as<br />

one of the original bands on the scene, Pansy Division has had a formidable<br />

impact on queercore participants, including fans and other artists,

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 23<br />

as evidenced in numerous articles in both the mainstream and queercore<br />

press. Second, their wide media exposure has thrust them (like it or not)<br />

into the mainstream musical spotlight, including a 1995 MTV special on<br />

queercore which featured the group. Their (relatively) high profile has<br />

thus placed a burden of "speaking for the movement" upon them. Jon<br />

Ginoli, Pansy Division's vocalist and principal songwriter, has stated<br />

that queercore as a term and a movement "is something that I embrace<br />

now" (Interview with author), which signals his support for queercore as<br />

a musical marker. Along with continued media visibility, it seems reasonable<br />

to anticipate Pansy Division's continued position as a prominent<br />

voice for queercore.<br />

In addition, as will be demonstrated in this analysis, Pansy Division's<br />

music and lyrics exhibit the most important characteristics of a<br />

sensibility of play. Since I am arguing that an explication of a playful<br />

sensibility and its representative tactical deployments can provide an<br />

important avenue for determining a subaltern group's motivations, I feel<br />

that a responsible discussion must provide concrete examples of play in<br />

practice. Future studies, it is hoped, may benefit from and expand upon<br />

discursive analyses of sensibilities, and can further develop the themes<br />

which I am exploring. Pansy Division provides an exemplary site for a<br />

preliminary examination of such themes and promises to uncover ways<br />

in which play might promote an empowering and potentially liberatory<br />

discourse for its participants. In this analysis I examine Pansy Division's<br />

music, lyrics, and nonmusical artistic expression (such as album.art and<br />

fashion) and aspects of their live concert performances which bear upon<br />

the discourse. As additional data to supplement my analysis, I consider<br />

opinions and commentary from vocalist and principal songwriter Jon<br />

Ginoli, including narratives gathered from a personal telephone interview<br />

with him which I conducted in January of 1996. Together, these<br />

investigations should provide a rigorous analysis of queercore's playful<br />

sensibility.<br />

Pansy Division's Musical Play<br />

Musically, Pansy Division exhibits many of the playfully subversive<br />

tendencies of early punk rock. The music is typically fast and raw,<br />

with an emphasis on distorted guitars and prominent percussive rhythms.<br />

For example, "I Can't Sleep," from the 1994 Outpunk Dance Party compilation,<br />

begins with a high-speed, scratchy staccato rhythm introduction<br />

which explodes into a raw, distorted three-chord arrangement. The musical<br />

performance is intentionally loose and even sloppy, with sour notes<br />

and other imperfections allowed to remain in the final recording. Vocals<br />

are out of tune and, at times, out of rhythm with the rest of the music,

24 • Popular Music and Society<br />

adding to the song's unpolished sound and feel. The song clocks in at<br />

1:30, which is typical of punk rock's intention of radically speeding up<br />

and shortening traditional conventions of pop arrangement. Over half of<br />

the twenty songs on Pansy Division's Pile Up album (a 1995 compilation<br />

of songs taken from their single releases, originally recorded<br />

between 1991 and 1995) display all of these fast, raw, and percussive<br />

musical characteristics.<br />

Other punk characteristics can be seen in Pansy Division's music as<br />

well. "Fuck Buddy" (1995) begins with an off-microphone shout of<br />

"one, two, three, four!" reminiscent of punk's send-up of early rock and<br />

roll conventions such as those employed by the Beatles. Other musical<br />

genres are parodied, such as in the song "Cowboys Are Frequently<br />

Secretly Fond of Each Other," which mocks conventions of country<br />

music. Often, songs are left to collapse into a cacophony of percussion<br />

and guitar feedback, adding dissonance and disrhythmia to the sound.<br />

Musical form itself thus becomes the terrain for parody and debasement<br />

of traditional popular musical conventions in much of Pansy Division's<br />

music.<br />

Such appropriations and excorporations, as it can be argued of early<br />

punk rock in general, are intended to disturb and mock the popular mainstream—as<br />

a mosquito on popular music's arm, so to speak. Ginoli<br />

states that his initial impetus for forming Pansy Division came from his<br />

association with punk rock in the late seventies and was largely a reaction<br />

to the perceived overblown, stagnant state of rock at the time:<br />

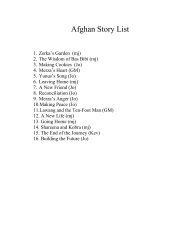

Promo photo of Pansy Division from their latest album, Wish I'd Taken<br />

Pictures. Courtesy of Lookout! Records.

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 25<br />

For me, punk was really good music.... I wanted something fast and exciting.<br />

At the time—the late seventies—the radio was just so bad. Everything was,<br />

like, REO Speed wagon/Foghat boogie rock or disco or really bad crappy pop.<br />

(Interview with author)<br />

In another interview, Ginoli states that Pansy Division is both a punk and<br />

a pop band, circulating between both categories (Vavra 14). Indeed, pop<br />

music sensibilities can be heard in some of their music, particularly<br />

taking into account the current and ongoing co-optation of punk rock<br />

into the popular mainstream. In any case, Pansy Division exhibits a predominant<br />

punk rock aesthetic in their musical form, arrangement, production<br />

values, and attitude.<br />

Pansy Division's Lyrical Play<br />

Pansy Division's song lyrics provide perhaps the most obvious evidence<br />

of a playful discursive sensibility. They display many of the carnivalesque<br />

characteristics which ground a playful sensibility. One of the<br />

most prevalent examples of carnival play can be seen in Pansy Division's<br />

lyrical emphasis on explicit subject matter—specifically, on the<br />

body and physical pleasures. For example, in the song "Ring of Joy," an<br />

explicit sexual reference to the body is made:<br />

Take a good long look at a buried treasure<br />

There between your cheeks, a hidden source of pleasure<br />

It's an orifice for elimination<br />

It's an orifice for exploration<br />

The song prescribes a pleasure to be derived from such self-exploration,<br />

playfully using "treasure" as a metaphor for the origin of bodily pleasure.<br />

In "Homo Christmas," another sexual exploit is suggested, again<br />

using a play of metaphor:<br />

We 'II push the packages<br />

Out of the way<br />

And after you 've unwrapped me<br />

Naked on the floor we'll play<br />

Here, the narrator seems to be engaged in a dialogue with his/her partner,<br />

or possibly is offering a proposition to him/her. In either case, the<br />

song vividly lays out an explicit scenario of potential sexual pleasure,<br />

described in terms of "play" (!).

26 • Popular Music and Society<br />

Finally, in a particularly explicit lyrical passage from "Fuck<br />

Buddy," a first-person narrative of a sexual encounter is described:<br />

Down and dirty, hot and squirty<br />

It's almost poetry<br />

The way his hair hangs down<br />

When he's on top of me<br />

This passage uses vivid language to describe a sexual encounter (or<br />

series of encounters) between the narrator and his/her partner. The word<br />

"buddy" in the song title seems to denote a friend as much as a partner—<br />

a casual relationship. This theme of casual and incidental sexual relations<br />

is evidenced in the lyrics of other Pansy Division songs as well,<br />

including "Strip U Down" and "I Can't Sleep." In using vivid language<br />

and linguistic tropes to explicitly describe various engagements in bodily<br />

pleasures and bodily acts, and in their depiction of such acts as offhanded<br />

and playfully hedonistic, Pansy Division's lyrics can thus be seen to<br />

embody the "grotesque realism" characteristic of the carnival scene.<br />

Another example of carnival play, some of which I have already<br />

demonstrated, can be seen in Pansy Division's extensive use of vulgarity<br />

and profanity in their lyrics. Profanity is used in many of the group's<br />

songs, including "Ring of Joy," "Denny (Naked)," "Jack U Off,"<br />

"Smells Like Queer Spirit," and "C.S.F." Profanity serves to intensify<br />

many of the explicit sexual themes in the songs, and it is undoubtedly<br />

meant to shock and annoy mainstream, straight sensibilities. But it also<br />

represents two other aspects of Pansy Division's music which help to<br />

explain the group's discursive motivations. Ginoli states that one of his<br />

intentions is to lyrically uncover the .base sexuality which drives all<br />

humans;<br />

Pop music, so much, deals with romance. The problem with a lot of pop music<br />

is that you hear all these romantic sentiments in songs, and really all they are is<br />

a sort of rationalization for sex. Like, "We're so romantically involved, now<br />

we're gonna have this wonderful business relationship." What we try. to do is<br />

sort of deconstruct that sort of thing and say, "Look, let's face it—sex is what<br />

it's about." You may couch it in all these romantic terms—and it's not like there<br />

isn't such a thing as romance to a certain extent—but I just wanted to get at the<br />

bare truth, which is that we're driven by sexuality. (Interview with author)<br />

He thus desires, through music, to express sexuality, viewing it as a<br />

repressed category of social behavior. But Ginoli also states that freedom<br />

of expression is an important aspect of his motivations. Referring to per-

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 27<br />

formance artist Karen Finley's influence on his attitude, he offers that<br />

"Just the idea to say things that were taboo inspired me to find whatever<br />

it was that I could say, instead of censoring yourself because you're<br />

afraid people don't want to hear it or hear about it, or how badly they'll<br />

react to it" (Interview with author). Thus, the freedom to express ideas<br />

publicly is also a motivation for Ginoli's often explicit and profane lyrical<br />

discourse.<br />

Clearly, Pansy Division's lyrics are explicit and sometimes vulgar.<br />

But it must be noted that there is an air of laughter and comic mockery<br />

evident in them, underscoring a comic and playful, rather than negative,<br />

tone. This point is crucial to a playful sensibility since, as I have shown,<br />

the carnivalesque atmosphere which grounds play stresses an antithetical<br />

counterpoint to negative laughter. Carnival profanity is ambivalent; its<br />

goal is not to hurt or destroy, but rather, to mock as a participant in the<br />

human comedy. This important difference between modern (negative)<br />

satire and carnival laughter is seen throughout Pansy Division's lyrics—<br />

evident even in song titles like "Touch My Joe Camel," a spoof on<br />

covert sexual imagery in modern advertising, and "Bill & Ted's Homosexual<br />

Adventure," a parody of the popular (and silly) early-nineties<br />

comedy movie. An objection can be raised that any communication,<br />

whether intentionally or unintentionally directed, may offend or degrade<br />

persons on any number of levels. I am also not arguing that much of<br />

Pansy Division's lyrical content is not intended to shock and upset—<br />

indeed, much of it undoubtedly serves exactly this function. However, I<br />

wish to stress that a sensibility of play signifies the distinction between<br />

an ambivalent self-reflexivity and a transcendent, self-serving negativity.<br />

Pansy Division's lyrics also demonstrate carnival play's intention of<br />

temporary escape from oppressive circumstances. Such an intention is<br />

seen in two lines from the final verse of "Smells Like Queer Spirit":<br />

The world's a mess, but for awhile<br />

We lick and suck and feel fine<br />

These lyrics allude to a temporary retreat (into a sexual encounter) from<br />

the "mess" of the world. There is a self-awareness in these lines, one<br />

which suggests that sex is only a temporary avoidance of "reality." In<br />

"Homo Christmas," another "temporal" solution is offered:<br />

Yourfamily<br />

Won't give you encouragement<br />

But let me give you<br />

Sexual nourishment

28 • Popular Music and Society<br />

Again, a sexual exploit is suggested as a temporary escape, this time<br />

from the oppression (or at least lack of encouragement) of one's family.<br />

These songs do not attempt to forecast or prescribe any "solutions" to<br />

society's ills—in this case, the oppressiveness of heteronormativity—but<br />

rather offer diversions and <strong>subversion</strong>s from the circumstances. In each<br />

of the examples above, the narrator of the song is situated as a participant<br />

within the circumstance. S/he is not above it, as an omniscient<br />

observer. In this way, Pansy Division's lyrics offer reflections on the<br />

human comedy—that is, the comedy in which we are all participants.<br />

Lyrics such as these thus attempt to negotiate an identity for queercore<br />

participants which also acknowledges their implication in the larger<br />

sociocultural milieu. Theirs is not a proposal for radical change. Rather,<br />

it is a tactical form of evasion and resistance. Such resistance can be<br />

therapeutic: Ginoli states that, though he recognizes that politics necessarily<br />

pervades their music and represents a motivation for their art, the<br />

band's major impetus was "the idea to do something that was really fun,<br />

and really funny, partly because so much gay art, or gay media, is sort of<br />

down and sad about all these terrible things that we've suffered in our<br />

lives. We wanted to show that it's not so bad" (Interview with author).<br />

Finally, Pansy Division's tactical appropriations and debasements<br />

of songs by popular artists playfully invert social hierarchies and thereby<br />

spectacularize their performances. Ginoli has claimed such practice as an<br />

important tactic for the group: "We're sort of seizing back the issue and<br />

saying, 'You're not going to use this song against us—we're going to<br />

use it against you' " (Interview with author). He cites two examples from<br />

the group's repertoire: Bob Mould's "The Biggest Lie" and a yet-unreleased<br />

version of the Police's song "On Any Other Day," in which certain<br />

words or phrases are strategically changed or modified to reflect a<br />

more queer interpretation. He adds that "other songs, just by the virtue of<br />

[our] doing them, take on a different context" (Interview with author).<br />

Thus, by inverting meanings in songs, Pansy Division succeeds in<br />

inverting straight/queer musical hierarchies as well, at least on an artistic<br />

level. Such temporal symbolic inversions are yet another hallmark of<br />

carnival play—one which celebrates an empowering voice for the<br />

oppressed. Spectacularizing or "queering" pop songs presents the popular<br />

musical mainstream with an uncomfortable twist. At the same time, it<br />

allows queercore participants, living simultaneously within and outside<br />

of the movement, to enjoy the irony in the joke.<br />

Pansy Division's Nonmusical Artistic Play<br />

Thus far I have examined playful elements within Pansy Division's<br />

musical discourse. There are other significant factors, however, which

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 29<br />

contribute to a playful sensibility. One important aspect of Pansy Division's<br />

discourse is their approach to art, as seen on their album, compact<br />

disc, and 7-inch record covers and in their liner notes. The artwork often<br />

depicts explicit sexual situations, and the group sometimes uses gay<br />

pornographic photographs on their record covers. Their records are usually<br />

relegated to a handful of independent record stores—most retail<br />

chains and many larger music stores choose not to stock them. Consequently,<br />

sales (as well as production) of the more explicitly adorned<br />

records are usually quite limited compared to that of other punk recordings.<br />

Here Pansy Division emphasizes the body and other features that<br />

would appear vulgar to straight and/ or conservative sensibilities. Again,<br />

Ginoli stresses his motivation in terms of freedom of expression:<br />

It's like, these bands that worry about what people are gonna think of their<br />

album cover, I just really have to wonder where they're coming from. We have<br />

the freedom to do these kinds of things, and maybe they'll get us in trouble. But<br />

it's just a matter of self-expression. Putting out sex as we have on our album<br />

covers as a male conventional sort of thing. '.. it's just a natural and normal sort<br />

of thing. If people find them titillating or obscene, ... I mean, I think Jesse<br />

Helms is obscene! (Interview with author)<br />

Emphasis on vulgarity and on bodily excesses and pleasures for Ginoli<br />

thus signifies his tactical artistic expression—another type of ambivalent<br />

laughter.<br />

Also present in Pansy Division's art is the use of photocollage, an<br />

effect of superimposed or "taped on" lettering, and other types of pastiche.<br />

This adds to the unprofessional, "do it yourself look which many<br />

punk rock groups employ in response to the slick packaging of most<br />

commercial album art. Especially evident in their 7-inch record art is a<br />

very plain, two-tone color motif, with offset, pastiched or handwritten<br />

lettering. The overall effect is akin to an impromptu flyer. Seven-inch<br />

artwork also frequently includes some type of caricature or cartoon art—<br />

again, a style employed in much punk rock 'zine and album art. Tactically,<br />

then, Pansy Division generally coheres with a punk rock aesthetic<br />

vis-à-vis artistic practices.<br />

Fashion also plays a role in Pansy Division's playful tactics.<br />

Though one cannot distinguish a particular, defining "look" for a Pansy<br />

Division fan, many traditional punk fashion characteristics are evident in<br />

fans' attire. At live concert performances, for example, an array of punk<br />

styles are apparent, including hair dyed in fluorescent colors and<br />

"mohawk"-style haircuts, ripped or disheveled clothing, body piercings<br />

(now a thoroughly co-opted practice, especially in youth culture), and

30 • Popular Music and Society<br />

accoutrements such as skull rings and safety pins. In punk, the body<br />

becomes a site for bricolage, giving an unfinishedness and openendedness<br />

to one's look. This carnivalesque tactic helps to dissolve<br />

the straight/queer binary among Pansy Division audiences, with punk<br />

pastiche serving as the deconstructive. Along with the various punk<br />

appropriations, one also sees queer appropriations of symbols of commodity<br />

culture. For example, on the back of the Pile Up album, Ginoli<br />

and bassist Chris Freeman are highlighted in close-up photographs<br />

wearing T-shirts. Freeman's shirt features a giant penis covering the<br />

entire front, while Ginoli's shirt is emblazoned with the words "Long<br />

Haired Fag." Such a term, traditionally used pejoratively against homosexuals<br />

(as is the term "queer" itself), is hence turned back against the<br />

mainstream, now transformed into a defiant identification badge. The<br />

giant penis is undoubtedly meant to shock but is also a way of turning<br />

the tables on culture through its own products, a way of saying, "I<br />

bought this T-shirt—how do you like it?" In this move, de Certeau's tactics<br />

of "making do" with the materials at one's disposal become apparent.<br />

The group members often perform in these and similar thematic<br />

shirts as well, as evidenced in photographs published in mainstream<br />

articles and 'zines. Thus, both fashion and artistic practices contribute<br />

tactically to Pansy Division's playful sensibility.<br />

Pansy Division's Performative Play<br />

Pansy Division's live concert performances represent an important<br />

dimension of queercore's often carnivalesque scene. To begin with, the<br />

group promotes a participatory experience between themselves and their<br />

audience. This is accomplished in three ways. The first can be readily<br />

seen as a ritual in which audience members climb up onto the stage and<br />

hurl themselves out into the audience, who (hopefully) catch them or at<br />

least break their fall. Originating in the formative years of punk rock,<br />

stagediving is a fairly common ritual among the current punk movement<br />

and other punk-influenced movements such as grunge and ska-core. In<br />

this way, Pansy Division can again be seen to align themselves with the<br />

aesthetics of punk ritual. However, as is not always the case with other<br />

bands and musical formations, Pansy Division actually encourages this<br />

behavior (much to the consternation of the concert security staff) and<br />

occasionally flail themselves into the audience, even in the middle of<br />

songs. There is a blurring between performer and audience which occurs<br />

in this ritual—a sense of unity and a deconstruction of power relations<br />

which invites the audience to participate in the spectacle's enactment;<br />

the audience, in effect, becomes not only a performer but part of the<br />

overall performance. Indeed, such behavior serves to spectacularize ritu-

<strong>Mapping</strong> Subversion • 31<br />

als such as traditional dancing and concert viewing, which are now<br />

replaced by stagediving and "moshing," a practice in which a group or<br />

groups of audience members create a circular mass of physical nudging<br />

and colliding off of one another.<br />

A second form of participation occurs as a result of Pansy Division's<br />

stage antics. Between songs, the group often playfully provokes<br />

its audience with "queer" jokes as well as "straight" jokes. This ironic<br />

behavior inserts laughter into occasionally shaky circumstances. For<br />

example, during a concert in 1994 in Winnipeg, Canada, Ginoli (playfully)<br />