Outcomes and Impacts of International Education ... - IDP Education

Outcomes and Impacts of International Education ... - IDP Education

Outcomes and Impacts of International Education ... - IDP Education

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Outcomes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: From<br />

<strong>International</strong> Student<br />

to Australian Graduate, the<br />

Journey <strong>of</strong> a Lifetime<br />

Edited by Melissa Banks <strong>and</strong> Alan Olsen

ISBN: 978-0-9758194-5-6<br />

Copyright statement: © 2008 <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd (ABN: 59 117 676 463)<br />

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means,<br />

without permission in writing from the publisher.

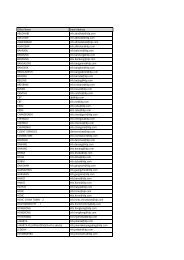

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Foreword<br />

Introduction<br />

Chapter 1: <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Students<br />

Chapter 2: <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Graduates<br />

Chapter 3: <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Alumni<br />

Chapter 4: <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Providers<br />

Chapter 5: <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> on Communities<br />

References List<br />

1<br />

3<br />

6<br />

23<br />

49<br />

62<br />

96<br />

110

Foreword<br />

<strong>International</strong> education makes a positive difference on many levels <strong>and</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong>’s major<br />

publication for 2008, <strong>Outcomes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: From <strong>International</strong><br />

Student to Australian Graduate, the Journey <strong>of</strong> a Lifetime, spells this out with clarity <strong>and</strong> detail.<br />

The book’s structure reflects the journey – from student, to graduate, to alumni – which an<br />

international student might take when he or she decides to study in Australia.<br />

Two important new pieces <strong>of</strong> research illuminate the journey. Firstly, there is yet more confirmation<br />

that the academic performance <strong>of</strong> international students is virtually identical to Australian students.<br />

This result comes from an analysis <strong>of</strong> the performance <strong>of</strong> nearly 200,000 students in Group <strong>of</strong> 8<br />

universities in 2007.<br />

Secondly, through a very detailed survey <strong>of</strong> nearly 2,000 alumni <strong>of</strong> the Australian Technology<br />

Network <strong>of</strong> Universities, we find out what Australia’s international students do after they graduate –<br />

where they live, what jobs they have, what they aspire to <strong>and</strong> what they think about their education.<br />

What emerges is a picture <strong>of</strong> graduates who are part <strong>of</strong> the global workforce, who establish global<br />

networks <strong>and</strong> who become part <strong>of</strong> Australia’s connectedness with Asian countries <strong>and</strong> beyond.<br />

<strong>International</strong> education also has an impact on Australia, the scale <strong>of</strong> which is only now coming to be<br />

appreciated. Two sections <strong>of</strong> the book examine this – one looking at the impact on Australian<br />

education providers <strong>and</strong> the other looking at the impact on the Australian community as a whole.<br />

It is my view that international education is a unique <strong>and</strong> valuable industry. Not only is it an activity<br />

<strong>of</strong> immense economic worth <strong>and</strong> benefit to Australia, but it achieves business success by fulfilling<br />

the aspirations <strong>of</strong> people who want better lives. Furthermore it generates influence <strong>and</strong> goodwill for<br />

Australia internationally. Over one million international students – potential future leaders <strong>and</strong><br />

influencers – have returned to their home countries after completing courses in Australia.<br />

It is particularly appropriate that this book is being launched at the 2008 Australian <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> Conference in Brisbane, where the authors are presenting its findings. This year’s<br />

conference theme, Global Citizens, Global Impact, very aptly sums up the book’s message.<br />

Finally, I would like thank the Group <strong>of</strong> 8 universities <strong>and</strong> the Australian Technology Network <strong>of</strong><br />

Universities for facilitating the research which provided the main new findings in the book. And I<br />

wish to commend the authors, Melissa Banks, Alan Olsen, Helen Cook, Rob Lawrence <strong>and</strong> Tim<br />

Dodd for producing a well-researched, rigorous <strong>and</strong> thought provoking piece <strong>of</strong> work.<br />

Anthony Pollock<br />

Chief Executive<br />

<strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd<br />

1<br />

Foreword | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Introduction<br />

Australia’s international student program has produced significant outcomes for international<br />

students. As international graduates contribute to the global workforce, establish global diasporic<br />

networks <strong>and</strong> join global brain circulation, it is apparent that Australia’s international student<br />

program is a key driver <strong>of</strong> Australia’s connectedness with Asia <strong>and</strong> beyond. The impacts go global.<br />

With an emphasis on these outcomes <strong>and</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> international education, <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd<br />

has undertaken in 2008 a series <strong>of</strong> research studies for presentation at the Australian <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> Conference <strong>and</strong> for publication as five papers in this book.<br />

Research Papers<br />

The five research papers commissioned by <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd each form a chapter <strong>of</strong> this book.<br />

In Chapter 1 <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Students, Alan Olsen explores the comparative<br />

academic performance <strong>of</strong> international <strong>and</strong> Australian students, using measures such as<br />

progression <strong>and</strong> retention, including international comparisons. The editor wishes to acknowledge<br />

the contribution <strong>of</strong> data regarding academic performance from the Group <strong>of</strong> 8 universities.<br />

In Chapter 2 <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Graduates, Melissa Banks <strong>and</strong> Robert Lawrence present the results <strong>of</strong><br />

new market research quantifying the outcomes for international graduates including employment,<br />

labour market <strong>and</strong> migration outcomes. The editor wishes to acknowledge the contribution <strong>of</strong> alumni<br />

data from the Australian Technology Network group <strong>of</strong> universities.<br />

In Chapter 3 <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Alumni, Melissa Banks asks “where are they now?”, looks at the extent<br />

to which Australia’s international alumni contribute to Australia’s connectedness in Asia <strong>and</strong> beyond<br />

<strong>and</strong> addresses issues such as brain circulation, global workforces <strong>and</strong> global diasporic networks.<br />

The editor wishes to acknowledge the contribution <strong>of</strong> alumni data from the Australian Technology<br />

Network group <strong>of</strong> universities.<br />

In Chapter 4 <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Providers, Helen Cook looks at the pr<strong>of</strong>ound impact <strong>of</strong> a<br />

high growth international student program on Australian education providers in the higher education,<br />

vocational education <strong>and</strong> training (VET), English language training (ELT) <strong>and</strong> school sectors.<br />

In Chapter 5 <strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> on Communities, Tim Dodd considers the impacts <strong>and</strong><br />

outcomes <strong>of</strong> international education on communities, looking at how international student programs<br />

impact the wider community in Australia <strong>and</strong> at the communities which international students create<br />

for themselves.<br />

3<br />

Introduction | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

About the Authors<br />

This research was commissioned, <strong>and</strong> the results are published, by <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd.<br />

Melissa Banks, Head <strong>of</strong> Research Services at <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd, is responsible for <strong>IDP</strong>’s<br />

corporate <strong>and</strong> industry research. Melissa has over 18 years experience in Australia’s international<br />

education industry encompassing roles across various sectors <strong>and</strong> education providers, <strong>and</strong> her<br />

own successful consultancy business. Melissa is widely known for her practical insights about the<br />

business <strong>of</strong> international education gained from her senior institutional <strong>and</strong> private industry roles in<br />

marketing, recruitment <strong>and</strong> research. Melissa was a joint author in 2007 <strong>of</strong> Global Student Mobility:<br />

An Australian Perspective Five Years On. She is a graduate <strong>of</strong> Deakin University <strong>and</strong> Monash<br />

University.<br />

Helen Cook has 20 years experience in Australia’s international education arena. Helen has held a<br />

range <strong>of</strong> institutional management positions covering international admissions, policy development,<br />

marketing communications, market strategy <strong>and</strong> planning <strong>and</strong> student recruitment. She is able to<br />

draw on an extensive network <strong>of</strong> industry contacts both within Australia <strong>and</strong> overseas. Helen’s most<br />

recent university role was as Executive Director, QUT <strong>International</strong>. She now works as a senior<br />

researcher for Strategy Policy <strong>and</strong> Research in <strong>Education</strong> Limited <strong>and</strong> is a board member for the<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Association <strong>of</strong> Australia.<br />

Tim Dodd is External Relations Manager for <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd. Previously, Tim was a journalist<br />

with the Australian Financial Review (AFR) where he established the weekly <strong>Education</strong> section in<br />

the AFR in 2003, setting a new benchmark in Australia for reporting <strong>and</strong> analysing higher education<br />

policy matters. From 1999 to 2003 Tim was the AFR South East Asia Correspondent based in<br />

Jakarta. Tim spent seven years from 1988 to 1995 based in the Canberra Press Gallery writing on<br />

economic policy for the AFR, <strong>and</strong> a year, 1984/1985, as a policy <strong>of</strong>ficer in the Department <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Prime Minister <strong>and</strong> Cabinet. Tim is a graduate <strong>of</strong> The University <strong>of</strong> Adelaide.<br />

Robert Lawrence is hailed as one <strong>of</strong> the world’s leading specialists in education market research,<br />

market planning <strong>and</strong> br<strong>and</strong> building. His experience includes the development <strong>of</strong> destination<br />

strategies for many national, state <strong>and</strong> provincial governments; over 60 universities across seven<br />

countries; <strong>and</strong> numerous organisations ranging from multinationals to government agencies. With<br />

extensive experience in market planning <strong>and</strong> communications, Robert is widely regarded as an<br />

expert in forecasting education dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> industry trends, audience needs <strong>and</strong> expectations, <strong>and</strong><br />

key influencing factors. Robert is a graduate <strong>of</strong> Queen Mary, University <strong>of</strong> London.<br />

Alan Olsen, an Australian living <strong>and</strong> working in Hong Kong, is Director <strong>of</strong> Strategy Policy <strong>and</strong><br />

Research in <strong>Education</strong> Limited www.spre.com.hk. Alan is a consultant in international education,<br />

carrying out research, strategy <strong>and</strong> policy advice for client institutions <strong>and</strong> organisations on<br />

international education, transnational education <strong>and</strong> international student programs. He has<br />

published extensively, with 31 items on Australian <strong>Education</strong> <strong>International</strong>’s Database <strong>of</strong> Research<br />

on <strong>International</strong> <strong>Education</strong> http://aei.dest.gov.au. He was joint author in 2007 <strong>of</strong> Global Student<br />

Mobility: An Australian Perspective Five Years On. Alan is a graduate <strong>of</strong> The University <strong>of</strong><br />

Sydney <strong>and</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Technology Sydney.<br />

4<br />

Introduction | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Acknowledgements<br />

The editors also wish to acknowledge the contribution <strong>of</strong> data from the Group <strong>of</strong> 8 (Go8) universities<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Australian Technology Network <strong>of</strong> Universities (ATN).<br />

In Melbourne, Racquel Shr<strong>of</strong>f, a graduate <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Madras, <strong>and</strong> Paresh Kevat, a graduate <strong>of</strong><br />

Massey University in New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, provided research assistance. In Hong Kong, Jen Spain, a<br />

graduate <strong>of</strong> The Australian National University, <strong>and</strong> Rebecca Wright, a graduate <strong>of</strong> Queensl<strong>and</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Technology, provided research assistance.<br />

5<br />

Introduction | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

1<br />

<strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> for Students<br />

Alan Olsen explores the comparative academic performance <strong>of</strong> international <strong>and</strong> Australian<br />

students, using measures such as progression <strong>and</strong> retention, including international comparisons.<br />

The editors wish to acknowledge the contribution <strong>of</strong> data regarding academic performance from the<br />

Group <strong>of</strong> 8 (Go8) universities.<br />

Background<br />

A study <strong>of</strong> the comparative academic performance in 2007 <strong>of</strong> the following three cohorts <strong>of</strong> students<br />

in Go8 universities in Australia was undertaken in 2008<br />

Australian students on campus in Australia<br />

international students on campus in Australia<br />

international students <strong>of</strong>fshore, resident outside Australia but studying at a Go8 university,<br />

including those at <strong>of</strong>fshore campuses <strong>and</strong> those international students studying by distance or<br />

online.<br />

All Go8 universities participated: The Australian National University, Monash University, The<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Adelaide, The University <strong>of</strong> Melbourne, The University <strong>of</strong> New South Wales, The<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Queensl<strong>and</strong>, The University <strong>of</strong> Sydney <strong>and</strong> The University <strong>of</strong> Western Australia.<br />

The study used student progress rates to measure <strong>and</strong> compare academic performance. Student<br />

progress rates are generated when students complete subjects successfully. The student progress<br />

rate is the ratio <strong>of</strong> successfully completed student load to total assessed student load, simply the<br />

ratio <strong>of</strong> subjects passed to subjects attempted. The study calculated mean student progress rates<br />

for groups <strong>of</strong> students <strong>and</strong> compared these means between groups, allowing comparison <strong>of</strong> the<br />

relative performance <strong>of</strong> groups <strong>of</strong> students.<br />

The definitive Australian study in this area is the Dobson, Sharma <strong>and</strong> Calderon 1998 paper The<br />

Comparative Performance <strong>of</strong> Overseas <strong>and</strong> Australian Undergraduates 1 , which provided an<br />

extensive background on the use <strong>of</strong> the student progress rate methodology. In that study,<br />

international bachelor degree students in 1996 passed 84.3% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong><br />

outperformed Australian bachelor degree students who passed 79.3% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted.<br />

In 2006, Olsen, Burgess <strong>and</strong> Sharma published The Comparative Academic Performance <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>International</strong> Students 2 , again using the student progress rate methodology. In that study <strong>of</strong><br />

338,445 full time students at all levels in 22 Australian universities in 2003, international students<br />

performed as well as Australian students. The 73,929 international students passed 88.8% <strong>of</strong> what<br />

they attempted; the 264,516 Australian students passed 89.4% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted.<br />

1 Dobson I, Sharma R <strong>and</strong> Calderon A 1998<br />

2 Olsen A, Burgess Z <strong>and</strong> Sharma R 2006<br />

6<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

In 2007 the then Australian Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Science <strong>and</strong> Training (DEST) published<br />

Appendix 4. Attrition Progress <strong>and</strong> Retention Rates for commencing bachelor students as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> Students 2006 [full year]: selected higher education statistics 3 . This put into the public<br />

domain for the first time information for each university on the comparative academic performance<br />

<strong>of</strong> international <strong>and</strong> Australian students, but specifically the population was commencing bachelor<br />

degree students.<br />

The DEST data enabled the comparison <strong>of</strong> student progress rates for international <strong>and</strong> Australian<br />

commencing bachelor degree students in 2006 for each university, with the Go8 universities<br />

highlighted in orange as in Chart 1.1 Student Progress Rates by Universities 2006.<br />

Chart 1.1<br />

Student Progress Rates by Universities 2006<br />

100<br />

95<br />

90<br />

<strong>International</strong> Student Progress Rate %<br />

85<br />

80<br />

75<br />

70<br />

65<br />

60<br />

60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100<br />

Domestic Student Progress Rate %<br />

Like the 1998 <strong>and</strong> 2006 studies, this study uses the student progress rate methodology. It involves<br />

two enhancements, in that it excludes postgraduate research students <strong>and</strong> adds a third cohort,<br />

<strong>of</strong>fshore students.<br />

The study includes international <strong>and</strong> Australian full time students in undergraduate <strong>and</strong><br />

postgraduate coursework programs who were enrolled in 2007. Specifically it includes study abroad<br />

<strong>and</strong> exchange students.<br />

3 Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Science <strong>and</strong> Training 2007<br />

7<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

The study excludes part time students, because there are no international part time students with<br />

which to compare Australian part time students, <strong>and</strong> excludes postgraduate research students on<br />

the ground that student progress units for research students are just about meaningless.<br />

The study compares student progress rates in 2007 for a total population <strong>of</strong> 195,694 students in the<br />

eight Go8 universities.<br />

Overall Student Progress Rate<br />

In Go8 universities in Australia in 2007, 195,694 students passed 91.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted.<br />

Their student progress rate was 91.8%.<br />

Across the eight Go8 universities, student progress rates ranged from 89.6% to 94.4%. The average<br />

was 91.8%, the median 91.8%. Overall, international students on campus in Australia passed 91.6%<br />

<strong>of</strong> what they attempted, international students <strong>of</strong>fshore 89.2% <strong>and</strong> Australian students 92.0%.<br />

Specifically, in 2007 the 46,812 international students on campus in Australia passed 91.6% <strong>of</strong> what<br />

they attempted, <strong>and</strong> did just as well as the 140,903 Australian students, who passed 92.0%. This is<br />

consistent with the 2006 study where, across 22 universities, the 73,929 international students on<br />

campus in Australia in 2003 passed 88.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted, <strong>and</strong> did just as well as the<br />

264,516 Australian students, who passed 89.4%.<br />

In this study, in terms <strong>of</strong> student progress rates<br />

women did better than men<br />

postgraduate coursework students did better than undergraduates<br />

international students on campus in Australia did as well as Australian students <strong>and</strong> did better<br />

than international students <strong>of</strong>fshore.<br />

Chart 1.2 Student Progress Rates by Groups compares the student progress rates for these<br />

seven groups with the total population.<br />

8<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.2<br />

Student Progress Rates by Groups<br />

88% 90% 92% 94% 96% 98% 100%<br />

Gender<br />

The population included 105,987 female students <strong>and</strong> 89,707 male students, as in Table 1.1<br />

Gender: Population.<br />

Table 1.1<br />

Gender: Population<br />

Female Male Total<br />

<strong>International</strong> Onshore 25,082 21,770 46,852<br />

<strong>International</strong> Offshore 4,318 3,621 7,939<br />

Australian 76,587 64,316 149,903<br />

Total 105,987 89,707 195,694<br />

In total, 54% <strong>of</strong> students in the study were women, consistent with the fact that 55% <strong>of</strong> students in<br />

Australian universities in 2007 were women.<br />

<strong>International</strong> female students onshore passed 93.1% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than<br />

international male students onshore (89.9%). <strong>International</strong> female students <strong>of</strong>fshore passed 90.9%<br />

<strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than international male students <strong>of</strong>fshore (87.2%). Australian<br />

female students passed 93.5% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than Australian male students<br />

(90.1%).<br />

Overall, female students passed 93.3% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than male students<br />

(89.9%), as in Table 1.2 Gender: Student Progress Rates.<br />

9<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Table 1.2<br />

Gender: Student Progress Rates<br />

Female Male Total<br />

<strong>International</strong> Onshore 93.1% 89.9% 91.6%<br />

<strong>International</strong> Offshore 90.9% 87.2% 89.2%<br />

Australian 93.5% 90.1% 92.0%<br />

Total 93.3% 89.9% 91.8%<br />

This gender difference was consistent with the 2006 study, where female students passed 91.6% <strong>of</strong><br />

what they attempted, <strong>and</strong> male students 86.5%.<br />

Level <strong>of</strong> Study<br />

The population in the study included 164,214 undergraduate students <strong>and</strong> 31,480 postgraduate<br />

coursework students, as in Table 1.3 Level <strong>of</strong> Study: Population.<br />

Table 1.3<br />

Level <strong>of</strong> Study: Population<br />

Undergraduate Postgraduate Coursework Total<br />

<strong>International</strong> Onshore 31,133 15,719 46,852<br />

<strong>International</strong> Offshore 6,711 1,228 7,939<br />

Australian 126,370 14,533 140,903<br />

Total 164,214 31,480 195,694<br />

34% <strong>of</strong> international students onshore were postgraduate coursework students, 15% <strong>of</strong> international<br />

students <strong>of</strong>fshore were postgraduate coursework students <strong>and</strong> 10% <strong>of</strong> Australian students were<br />

postgraduate coursework students. In total, 16% <strong>of</strong> students in the study were postgraduate<br />

coursework students.<br />

<strong>International</strong> postgraduate coursework students onshore passed 95.0% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong><br />

did better than international undergraduate students onshore (89.9%). <strong>International</strong> postgraduate<br />

coursework students <strong>of</strong>fshore passed 95.3% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than<br />

international undergraduate students <strong>of</strong>fshore (88.1%). Australian postgraduate coursework<br />

students passed 94.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than Australian undergraduate<br />

students (91.6%).<br />

Overall, postgraduate coursework students passed 94.9% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better<br />

than undergraduate students (91.2%), as in Table 1.4 Level <strong>of</strong> Study: Student Progress Rates.<br />

10<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Table 1.4<br />

Level <strong>of</strong> Study: Student Progress Rates<br />

Undergraduate Postgraduate Coursework Total<br />

<strong>International</strong> Onshore 89.9% 95.0% 91.6%<br />

<strong>International</strong> Offshore 88.1% 95.3% 89.2%<br />

Australian 91.6% 94.8% 92.0%<br />

Total 91.2% 94.9% 91.8%<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students<br />

Overall, international students on campus in Australia (91.6%) did as well as Australian students<br />

(92.0%) <strong>and</strong> did better than international students <strong>of</strong>fshore (89.2%), as in Table 1.5 <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> Australian Students: Student Progress Rates.<br />

Table 1.5<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students: Student Progress Rates<br />

Population Student Progress Rate<br />

<strong>International</strong> Onshore 46,852 91.6%<br />

<strong>International</strong> Offshore 7,939 89.2%<br />

Australian 140,903 92.0%<br />

Total 195,694 91.8%<br />

Broad Field <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong><br />

Student progress rates were compared for students in Natural <strong>and</strong> Physical Sciences, Information<br />

Technology, Engineering <strong>and</strong> Related Technologies, Architecture <strong>and</strong> Building, Agriculture,<br />

Environmental <strong>and</strong> Related Studies, Health, <strong>Education</strong>, Management <strong>and</strong> Commerce, Society <strong>and</strong><br />

Culture <strong>and</strong> Creative Arts 4 .<br />

Student progress rates varied across these ten Broad Fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> as in Table 1.6 <strong>and</strong> Chart<br />

1.3 Broad Field <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: Student Progress Rates.<br />

4 There is an eleventh field, Food, Hospitality <strong>and</strong> Personal Services, but there were no students in<br />

this field in Go8 in 2007<br />

11<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Table 1.6<br />

Broad Field <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: Student Progress Rates<br />

Field Population Student Progress Rate<br />

Management/Commerce 44,365 91.1%<br />

Society/Culture 43,627 90.7%<br />

Health 28,006 96.4%<br />

Science 21,998 90.7%<br />

Engineering 21,349 90.0%<br />

Creative Arts 11,160 93.8%<br />

<strong>Education</strong> 7,779 94.8%<br />

Architecture/Build 6,158 93.5%<br />

IT 5,035 84.9%<br />

Agriculture/Env 3,557 88.7%<br />

Chart 1.3<br />

Broad Field <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: Student Progress Rates<br />

84% 86% 88% 90% 92% 94% 96% 98% 100%<br />

Overall, across all fields <strong>of</strong> education, Go8 students passed 91.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted. Students<br />

in Health, <strong>Education</strong>, Creative Arts, <strong>and</strong> Architecture/Building did better than this, <strong>and</strong> did better<br />

than students in Management/Commerce, Society/Culture, Science, Engineering,<br />

Agriculture/Environment <strong>and</strong> IT.<br />

Across these ten Broad Fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, student progress rates were compared between<br />

international students onshore, international students <strong>of</strong>fshore <strong>and</strong> Australian students, as in Table<br />

1.7 <strong>and</strong> Chart 1.4 Broad Fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students. The<br />

performance <strong>of</strong> one international <strong>of</strong>fshore student in Agriculture/Environment was not included in the<br />

table or the chart.<br />

12<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Table 1.7<br />

Broad Fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students<br />

Population<br />

Student Progress Rate<br />

Field<br />

Int Int<br />

Int Int<br />

Onshore Offshore Australian Onshore Offshore Australian<br />

Mgt/Com 19,090 3,039 22,236 91.0% 88.5% 91.5%<br />

Soc/Culture 5,876 805 36,946 90.9% 89.3% 90.7%<br />

Health 4,455 825 22,726 96.1% 93.6% 96.6%<br />

Science 3,318 1,130 17,550 91.9% 91.7% 90.4%<br />

Engineering 5,456 912 14,981 89.8% 91.0% 90.0%<br />

Creative 1,782 282 9,096 94.8% 88.8% 93.8%<br />

<strong>Education</strong> 857 358 6,564 96.8% 90.0% 94.8%<br />

Arch/Build 1,473 51 4,634 92.2% 94.0% 94.0%<br />

IT 2,125 426 2,484 88.0% 81.6% 82.9%<br />

Ag/Env 512 3,044 91.6% 88.3%<br />

Chart 1.4<br />

Broad Fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>: <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students<br />

IT<br />

Ag/Env<br />

Business<br />

98%<br />

96%<br />

94%<br />

92%<br />

90%<br />

88%<br />

86%<br />

84%<br />

82%<br />

80%<br />

Arts<br />

Health<br />

<strong>International</strong><br />

Onshore<br />

<strong>International</strong><br />

Offshore<br />

Australian<br />

Arch/Build<br />

Sci<br />

<strong>Education</strong><br />

Engineering<br />

Creative Arts<br />

13<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Home Countries<br />

The Go8 universities reported international country codes for 46,438 international students on<br />

campus in Australia. The students came from 179 countries, with 90 countries each the source <strong>of</strong><br />

fewer than 10 students.<br />

There were 21 home countries with 200 students or more in Go8 universities, <strong>and</strong> these 21<br />

countries made up 91% <strong>of</strong> the international student population, on campus in Australia, as in Table<br />

1.8 Home Country <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> Students Onshore: Student Progress Rates.<br />

Table 1.8<br />

Home Country <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> Students Onshore: Student Progress Rates<br />

Population Student Progress Rate<br />

China 14,291 89.1%<br />

Malaysia 5,724 94.2%<br />

Singapore 4,231 94.7%<br />

HK 3,515 90.1%<br />

Indonesia 2,953 94.0%<br />

US 2,211 96.4%<br />

India 1,738 90.2%<br />

Korea 1,427 85.9%<br />

Vietnam 895 92.8%<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong> 858 94.4%<br />

Japan 739 90.6%<br />

Taiwan 699 90.7%<br />

Canada 637 97.5%<br />

Germany 464 94.2%<br />

Sri Lanka 395 89.4%<br />

Brunei 284 90.9%<br />

Pakistan 268 95.7%<br />

Mauritius 258 92.4%<br />

Norway 237 95.1%<br />

Saudi Arabia 214 88.6%<br />

Bangladesh 200 88.3%<br />

Chart 1.5 Home Country <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> Students Onshore: Student Progress Rates on the<br />

following page displays the student progress rates for these 21 countries, with some colour coding<br />

into regions.<br />

14<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.5<br />

Home Country <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> Students Onshore: Student Progress Rates<br />

100%<br />

98%<br />

96%<br />

94%<br />

92%<br />

90%<br />

88%<br />

86%<br />

84%<br />

82%<br />

80%<br />

Staying the Course<br />

Forthcoming research on attrition <strong>and</strong> retention in Australian universities 5 also enables some<br />

comparisons between academic outcomes <strong>of</strong> international <strong>and</strong> Australian students.<br />

The nouns retention <strong>and</strong> attrition do not lend themselves readily to active verbs. In the forthcoming<br />

report, students who are counted in retention figures stay the course, students who are counted in<br />

attrition figures drop out. The expression staying the course, used in the title, is taken from the UK<br />

National Audit Office 2007 report Staying the Course: The Retention <strong>of</strong> Students in Higher<br />

<strong>Education</strong> 6 . The House <strong>of</strong> Commons Committee <strong>of</strong> Public Accounts kept this expression in its 2008<br />

report Staying the Course: The Retention <strong>of</strong> Students on Higher <strong>Education</strong> Courses 7 .<br />

The concepts <strong>of</strong> attrition <strong>and</strong> retention need some clarity.<br />

5 Olsen A 2008a<br />

6 National Audit Office 2007<br />

7 House <strong>of</strong> Commons Committee <strong>of</strong> Public Accounts 2008<br />

15<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

In this forthcoming study, retention simply is the inverse <strong>of</strong> attrition, <strong>and</strong> 2006 is the base year, as<br />

follows<br />

Attrition = (T-C-G)/T (the proportion <strong>of</strong> students in year 2006 who neither completed nor returned<br />

in year 2007)<br />

Retention = Inverse <strong>of</strong> Attrition = (C+G)/T (the proportion <strong>of</strong> students in year 2006 who either<br />

completed or returned in year 2007)<br />

where<br />

T is Total number <strong>of</strong> students enrolled in 2006<br />

C is number <strong>of</strong> students in population T who continued in 2007<br />

G is number <strong>of</strong> students in population T who completed in 2006<br />

example<br />

If, <strong>of</strong> 100 students in 2006, 30 graduated in 2006 <strong>and</strong> 60 continued in 2007<br />

Attrition = (100-60-30)/100 = 10%<br />

Retention = Inverse <strong>of</strong> Attrition = (60+30)/100 = 90%.<br />

In this forthcoming study <strong>of</strong> 485,983 students in 32 Australian universities in 2006, the retention<br />

figure was 89.5%; the attrition figure was 10.5%. 89.5% <strong>of</strong> students in 2006 stayed the course,<br />

10.5% dropped out.<br />

This study <strong>of</strong> retention <strong>and</strong> attrition <strong>of</strong> Australian <strong>and</strong> international students was carried out with the<br />

cooperation <strong>of</strong> the Australian Universities <strong>International</strong> Directors’ Forum (AUIDF), the forum <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>International</strong> Directors in the 38 universities that are members <strong>of</strong> Universities Australia. 32<br />

universities chose to participate in the study.<br />

The base student population included both international <strong>and</strong> Australian students who were enrolled<br />

in an award course in at least one reporting period in 2006, who were studying full time on campus<br />

in Australia, <strong>and</strong> excluding postgraduate research students. The study excluded <strong>of</strong>fshore students,<br />

external students, part time students, postgraduate research students <strong>and</strong> non-award students.<br />

Specifically, study abroad <strong>and</strong> exchange students were excluded as non-award students.<br />

In 2007 the then DEST published Appendix 4. Attrition Progress <strong>and</strong> Retention Rates for<br />

commencing bachelor students as part <strong>of</strong> Students 2006 [full year]: selected higher education<br />

statistics 8 . This put into the public domain for the first time information for each university on the<br />

comparative attrition rates <strong>of</strong> international <strong>and</strong> Australian students, but specifically the population<br />

was commencing bachelor degree students.<br />

The DEST data enabled the comparison <strong>of</strong> attrition rates for international <strong>and</strong> Australian<br />

commencing bachelor degree students in 2005 for each university, as in Chart 1.6 Attrition Rates<br />

by Universities 2005.<br />

8<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Science <strong>and</strong> Training 2007<br />

16<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.6<br />

Attrition Rates by Universities 2005<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

<strong>International</strong>Attrition Rate<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40%<br />

Domestic Attrition Rate<br />

In the 2008 study <strong>of</strong> 485,983 students in 32 Australian universities in 2006<br />

women stayed the course better than men<br />

undergraduates did better than postgraduate coursework students<br />

international students stayed the course better than Australian students.<br />

Chart 1.7 Attrition Rates by Groups compares the attrition rates for these six groups with the total<br />

population.<br />

17<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.7<br />

Attrition Rates by Groups<br />

7.0% 7.5% 8.0% 8.5% 9.0% 9.5% 10.0% 10.5% 11.0% 11.5% 12.0%<br />

Overall, 7.6% <strong>of</strong> the 102,686 international students dropped out, staying the course better than the<br />

383,297 Australian students, 11.3% dropped out, as in Table 1.9 <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian<br />

Students: Attrition.<br />

Table 1.9<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students: Attrition<br />

Population<br />

Attrition<br />

<strong>International</strong> 102,686 7.6%<br />

Australian 383,297 11.3%<br />

Total 485,983 10.5%<br />

Across the population, 99.8% <strong>of</strong> students were aged between 17 <strong>and</strong> 60. Overall, 10.5% <strong>of</strong> students<br />

dropped out.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> staying the course, students aged 19 to 23, 57.5% <strong>of</strong> the overall student population, did<br />

better than this.<br />

15.8% <strong>of</strong> 17 year olds (6.1% <strong>of</strong> the student population) <strong>and</strong> 12.1% <strong>of</strong> 18 year olds (13.1% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

student population) dropped out, suggesting that slightly older students stay the course better,<br />

perhaps benefiting from experiences such as gap years. But this study did not distinguish between<br />

freshers <strong>and</strong> sophomores.<br />

From 23 years old on, attrition rates increase with age.<br />

Attrition rates across age groups were compared between international <strong>and</strong> Australian students, as<br />

in Chart 1.8 Age: <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students. At every age, international students<br />

stayed the course better than Australian students.<br />

18<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.8<br />

Age: <strong>International</strong> <strong>and</strong> Australian Students<br />

80,000<br />

70,000<br />

60,000<br />

Students in Age Group<br />

Domestic Attrition<br />

<strong>International</strong> Attrition<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

50,000<br />

15%<br />

40,000<br />

30,000<br />

10%<br />

20,000<br />

10,000<br />

5%<br />

0<br />

0%<br />

For the 32 universities, attrition rates for international students were compared with attrition rates for<br />

Australian students. In 27 universities, international students stayed the course better than<br />

Australian students <strong>and</strong> in five universities Australian students stayed the course better than<br />

international students.<br />

<strong>International</strong> Comparisons<br />

<strong>International</strong> comparisons are more readily available for retention than for student progress.<br />

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation <strong>and</strong> Development (OECD) defines survival rates for<br />

university undergraduate students as representing the proportion <strong>of</strong> those who enter such a<br />

program who go on to graduate from such a program.<br />

OECD in <strong>Education</strong> at a Glance 2007: OECD Indicators 9 compared survival rates in 2004.<br />

Against an OECD average <strong>of</strong> 71.0%, the figure for Australia was 67.3%, as in Chart 1.9 OECD<br />

Survival Rates.<br />

9 Organisation for Economic Cooperation <strong>and</strong> Development 2007<br />

19<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 1.9<br />

OECD Survival Rates<br />

50% 55% 60% 65% 70% 75% 80% 85% 90% 95%<br />

Japan<br />

Irel<strong>and</strong><br />

Korea<br />

Greece<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Belgium (Fl.)<br />

Spain<br />

Turkey<br />

Germany<br />

OECD average<br />

Finl<strong>and</strong><br />

Mexico<br />

Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

Portugal<br />

Australia<br />

Icel<strong>and</strong><br />

Pol<strong>and</strong><br />

Austria<br />

Czech Republic<br />

Hungary<br />

Sweden<br />

New Zeal<strong>and</strong><br />

United States<br />

67.3%<br />

71.0%<br />

The OECD survival rate for US in 2004 was 53.7%. In the Summer 2008 issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

Higher <strong>Education</strong>, Arthur M Hauptman 10 commented on participation <strong>and</strong> persistence in US<br />

Another traditional means <strong>of</strong> comparing OECD countries is persistence rates—the proportion <strong>of</strong><br />

entering students who complete their programs. Periodic longitudinal surveys <strong>of</strong> students<br />

entering universities in the United States suggest that about half <strong>of</strong> them receive a degree within<br />

six years. For community college students, the degree completion rate in the United States is<br />

much lower—certainly less than 20 percent <strong>and</strong> perhaps less than 10 percent, as many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

students who enroll do not plan to receive a degree. The view is that the United States has<br />

tended to be below the average <strong>of</strong> many other countries in terms <strong>of</strong> persistence, in part because<br />

as one <strong>of</strong> the first <strong>of</strong> the mass or universal systems in the world, the United States has adhered<br />

to the policy <strong>of</strong> letting more <strong>and</strong> more people try higher education <strong>and</strong> not worrying as much<br />

about how many complete their programs.<br />

The OECD survival rate for UK in 2004 was 77.7%. The UK National Audit Office 11 in 2007 reported<br />

on two measures <strong>of</strong> retention<br />

the completion rate, the proportion <strong>of</strong> starters in a year who continue their studies until they<br />

obtain their qualification, with no more than one consecutive year out <strong>of</strong> higher education (As<br />

10 Hauptman A M 2008<br />

11 National Audit Office 2007<br />

20<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

higher education courses take years to complete, an expected completion rate is calculated by<br />

the Higher <strong>Education</strong> Statistics Agency. Data to check whether the expected rates are close to<br />

the actual completion rates has only recently become available.)<br />

the continuation rate, the more immediate measure <strong>of</strong> retention, the proportion <strong>of</strong> an institution’s<br />

intake which is enrolled in higher education in the year following their first entry to higher<br />

education.<br />

The National Audit Office concluded<br />

From the published performance indicators, <strong>of</strong> the 256,000 full-time, first-degree students<br />

starting higher education in 2004-05, 91.6 per cent continued into their second year. Also, the<br />

projected outcomes table shows that 78.1 per cent are expected to qualify with a first degree,<br />

with a further 2.2 per cent expected to obtain a lower qualification, <strong>and</strong> 5.8 per cent expected to<br />

transfer to another institution to continue their studies.<br />

The OECD survival rate for New Zeal<strong>and</strong> in 2004 was 54.4%. In the March 2005 issue <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Higher <strong>Education</strong> Policy <strong>and</strong> Management, David Scott 12 reported research on<br />

completion rates for domestic undergraduates in New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. Of domestic students commencing<br />

bachelor degrees at public providers in 1998, 46% had completed successfully five years later, by<br />

2002, <strong>and</strong> 7% were still studying.<br />

The Gender Agenda<br />

A comment on the extent to which girls do better than boys, <strong>and</strong> on the importance <strong>of</strong> taking gender<br />

into account in research on outcomes <strong>of</strong> higher education, may be appropriate.<br />

In Go8 in 2007, female students passed 93.3% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted <strong>and</strong> did better than male<br />

students (89.9%). This gender difference was consistent with the 2006 study <strong>of</strong> 22 universities in<br />

2003, where female students passed 91.6% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted; male students 86.5%.<br />

In 32 universities in Australia in 2006, 9.9% <strong>of</strong> female students dropped out, staying the course<br />

better than male students; 11.2% dropped out.<br />

From the 2005 study in New Zeal<strong>and</strong> 13<br />

Women are more likely to complete a tertiary qualification successfully than men. For degreelevel<br />

qualifications <strong>and</strong> below, the rate at which men complete is 6% to 9% lower than the rate<br />

for women.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> outgoing international student mobility, a study <strong>of</strong> 37 universities in Australia in 2007 14<br />

found that women dominated all types <strong>of</strong> international study experiences. The 37 universities<br />

reported that 57.5% <strong>of</strong> students with international study experiences in 2007 were women. This is<br />

similar to the gender gap in US, where 65.5% <strong>of</strong> all study abroad students in 2005/06 were women.<br />

12 Scott D 2005<br />

13 Scott D 2005<br />

14 Olsen A 2008b<br />

21<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Girls do better than boys to the extent that, in any research on outcomes <strong>of</strong> higher education, it may<br />

be that a cohort dominated by women will do better than a cohort dominated by men. For this<br />

reason, gender needs to be on the agenda in any research on academic outcomes.<br />

<strong>Outcomes</strong><br />

Go8 is a coalition <strong>of</strong> leading Australian universities, intensive in research <strong>and</strong> comprehensive in<br />

general <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional education. In this elite group <strong>of</strong> Australian universities, 195,694 students in<br />

2007 passed 91.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted.<br />

Specifically, in 2007 the 46,812 international students on campus in Australia passed 91.6% <strong>of</strong> what<br />

they attempted, <strong>and</strong> did just as well as the 140,903 Australian students, who passed 92.0%. This is<br />

consistent with the 2006 study where, across 22 universities, the 73,929 international students on<br />

campus in Australia in 2003 passed 88.8% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted, <strong>and</strong> did just as well as the<br />

264,516 Australian students, who passed 89.4%.<br />

In 2007, 7,939 international students <strong>of</strong>fshore, resident outside Australia but studying at a Go8<br />

university, including those at <strong>of</strong>fshore campuses <strong>and</strong> those international students studying by<br />

distance or online, passed 89.2% <strong>of</strong> what they attempted.<br />

Go8 universities are attracting talented international students to Australia, are setting entry<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards at about the right levels <strong>and</strong> are achieving successful outcomes in educating these<br />

international students. In Go8 universities, international students in Australia do just as well as<br />

Australian students in key fields such as Management <strong>and</strong> Commerce, Society <strong>and</strong> Culture, Health<br />

<strong>and</strong> Engineering, <strong>and</strong> do a little bit better in Science.<br />

<strong>International</strong> students in Australia also have successful outcomes in terms <strong>of</strong> staying the course. Of<br />

102,686 international students in 32 Australian universities in 2006, 92.4% completed or continued,<br />

staying the course better than the 88.7% <strong>of</strong> 383,279 Australian students who completed or<br />

continued.<br />

22<br />

Chapter 1 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

2<br />

<strong>Outcomes</strong> for Graduates<br />

Melissa Banks <strong>and</strong> Robert Lawrence present the results <strong>of</strong> new market research quantifying the<br />

outcomes for international graduates including employment, labour market <strong>and</strong> migration outcomes.<br />

The editors wish to acknowledge the contribution <strong>of</strong> alumni data from the Australian Technology<br />

Network <strong>of</strong> Universities.<br />

Introduction<br />

The significance <strong>of</strong> Australia’s international student program is <strong>of</strong>ten measured in terms <strong>of</strong> scale, its<br />

economic contribution <strong>and</strong> more recently its contribution to Australia’s labour market, yet little is<br />

known about the outcomes for its graduates.<br />

Immediate employment outcomes, four months post graduation, are measured by Graduate<br />

Careers Australia through the Graduate Destination Survey. The Australian Bureau <strong>of</strong> Statistics<br />

reports export earnings, universities report revenue from international student fees <strong>and</strong> international<br />

student enrolments through Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Employment <strong>and</strong> Workplace Relations<br />

(DEEWR) submissions, Australian <strong>Education</strong> <strong>International</strong> (AEI) reports international student<br />

enrolments <strong>and</strong> commencing enrolments across all sectors, <strong>and</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Immigration <strong>and</strong><br />

Citizenship (DIAC) reports student visa <strong>and</strong> migration statistics.<br />

We know that in 2007/08 international education contributed $13.7 billion to the Australian<br />

economy 15 , <strong>and</strong> that revenue from international student fees contributed an average 14.9% <strong>of</strong> total<br />

university revenues in 2006 16 . In July 2008 there were a total <strong>of</strong> 459,692 international students<br />

enrolled in Australian education institutions across all sectors, 177,954 <strong>of</strong> these were in higher<br />

education 17 <strong>and</strong> in 2007 international students represented 19.4% <strong>of</strong> all students studying onshore<br />

in Australia’s universities 18 . There are many measures <strong>of</strong> Australia’s international student program<br />

yet none measure the outcomes for our graduates.<br />

Australia first accepted international students into its higher education system via the Colombo Plan<br />

for Cooperative Economic Development in South <strong>and</strong> South East Asia in the 1950s. Australia’s<br />

international student program has changed significantly since then in its scale, scope <strong>and</strong> intent. Yet<br />

despite the scale <strong>and</strong> longevity <strong>of</strong> Australia’s international student program, little is known about our<br />

graduates.<br />

15 Australian Bureau <strong>of</strong> Statistics 2008c<br />

16 Bradley et al 2008<br />

17 Australian <strong>Education</strong> <strong>International</strong> 2008a<br />

18 Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Employment <strong>and</strong> Workplace Relations 2007<br />

23<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Some studies have traced the outcomes for international scholarship recipients who returned to<br />

their home countries on completion <strong>of</strong> their studies. These studies have reported positive outcomes<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> graduates’ career <strong>and</strong> personal development but questioned the appropriateness <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Australian education to local conditions to which graduates return 19 . But today, anecdotally, we<br />

know that not all graduates return home <strong>and</strong>, as privately funded students, graduates will have<br />

choices about their employment <strong>and</strong> career directions that will be very different from those <strong>of</strong><br />

scholarship recipients.<br />

This chapter provides the results <strong>of</strong> new market research quantifying the many <strong>and</strong> various<br />

outcomes for international graduates including employment, <strong>and</strong> labour market <strong>and</strong> migration<br />

outcomes building on the prevailing measures <strong>of</strong> international education on Australia, the economy,<br />

the labour market <strong>and</strong> on our providers.<br />

The Study<br />

In order to examine the journey <strong>of</strong> Australian tertiary educated international graduates, <strong>IDP</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd (<strong>IDP</strong>) sought the collaborative support <strong>of</strong> the five university members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Australian Technology Network <strong>of</strong> Universities (ATN) (Curtin University <strong>of</strong> Technology, Queensl<strong>and</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Technology, RMIT University, University <strong>of</strong> South Australia, <strong>and</strong> University <strong>of</strong><br />

Technology Sydney) to explore the journeys <strong>of</strong> their international alumni.<br />

To qualify for this study, graduates must have completed at least 12 months <strong>of</strong> study on campus in<br />

Australia <strong>and</strong> must have been enrolled in an undergraduate or postgraduate coursework program.<br />

Graduates from 2005 or earlier were specifically targeted in order to provide some insights as to<br />

where they are now, where they have been, what they have been doing <strong>and</strong> what they are likely to<br />

do next.<br />

This is the only survey <strong>of</strong> its kind to build our knowledge <strong>of</strong> what actually happens to our graduates<br />

after graduation. The objectives <strong>of</strong> this exercise were<br />

where possible, to quantify the actual outcomes for a group <strong>of</strong> international graduates from<br />

selected Australian universities in terms <strong>of</strong> their employment <strong>and</strong> career outcomes, <strong>and</strong><br />

residency outcomes including locating graduates: where they are now <strong>and</strong> where they have<br />

been<br />

to measure international graduate perceptions <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> their Australian study experience<br />

based on their experiences post graduation<br />

to gain a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the ongoing benefits international graduates provide to<br />

Australia after completion <strong>of</strong> their studies.<br />

The research was commissioned by <strong>IDP</strong> in mid-2008 <strong>and</strong> was undertaken by Robert Lawrence <strong>of</strong><br />

Prospect Research. It is arguably the most in-depth Australian international alumni investigation yet<br />

undertaken, not only because <strong>of</strong> the collaborative nature <strong>of</strong> the study, but also the breadth <strong>and</strong><br />

depth <strong>of</strong> the enquiry lines.<br />

19 Cuthbert D, Smith W <strong>and</strong> Boey J 2008<br />

24<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Methodology <strong>and</strong> Sample<br />

The methodology for this research project consisted <strong>of</strong> an online survey distributed by each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ATN universities to their international alumni. Eligible alumni were invited to participate in the survey<br />

prior to <strong>and</strong> during the survey going live over a four week period, with data collected online <strong>and</strong> in<br />

real time.<br />

In total, the survey was distributed to approximately 8,000 graduates with a validated return <strong>of</strong> 1,940,<br />

a response rate <strong>of</strong> 25%.<br />

The aggregate <strong>of</strong> responses is used in this paper together with several banners<br />

age b<strong>and</strong>s: up to 26 years <strong>of</strong> age, 27 to 30 years <strong>of</strong> age <strong>and</strong> 31 years <strong>of</strong> age <strong>and</strong> over<br />

nationality b<strong>and</strong>s: specifically, the six largest sample markets <strong>of</strong> Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore,<br />

Hong Kong, India <strong>and</strong> China; other represented nationalities, <strong>of</strong> which there were 49, are listed<br />

under the heading ‘other’<br />

by major field <strong>of</strong> study: Business, Accounting <strong>and</strong> Finance, Engineering, Information Technology,<br />

Health <strong>and</strong> Medicine, Arts <strong>and</strong> Humanities, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Education</strong>; other fields <strong>of</strong> study have been<br />

included under the heading ‘other’.<br />

In interpreting the results there are several important skews which need to be taken into<br />

consideration<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

under nationality, 139 students cited their nationality as Australian, even though they were most<br />

definitely international students up to the point <strong>of</strong> graduation, a finding in itself<br />

fields relating to Accountancy <strong>and</strong> Finance, such as economics <strong>and</strong> actuarial studies, have been<br />

included under this heading<br />

social sciences have been included under the heading Arts <strong>and</strong> Humanities<br />

allied medical fields, such as psychology, pharmacy <strong>and</strong> optometry have been included under<br />

Health <strong>and</strong> Medicine.<br />

The final sample was 1,940.<br />

Chart 2.1 Sample by Nationality shows the major nationality cohorts, with Malaysia (552),<br />

Indonesia (263), Singapore (250), Hong Kong (139), India (101) <strong>and</strong> China (65) the six largest<br />

nationality groups. This distribution <strong>of</strong> responses by nationality reflects the enrolment pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong><br />

international students in Australian higher education in early to mid-2000 when China <strong>and</strong> India<br />

were only emerging as key source markets.<br />

25<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 2.1<br />

Sample by Nationality<br />

Other Countries<br />

UK<br />

Norway<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

China<br />

India<br />

Australia<br />

HK<br />

Singapore<br />

Indonesia<br />

Malaysia<br />

0 100 200 300 400 500 600<br />

Chart 2.2 Sample by Field <strong>of</strong> Study shows the sample segmented by field <strong>of</strong> study. Business has<br />

been separated from Accounting <strong>and</strong> Finance. Business represents the largest sample group by<br />

field <strong>of</strong> study at 474 participants. This is followed by Accounting <strong>and</strong> Finance (315), Engineering<br />

(225), Information Technology (171), Health <strong>and</strong> Medicine (152), Arts <strong>and</strong> Humanities (124) <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Education</strong> (86). The remaining 388 participants are included under the heading ‘other’.<br />

Chart 2.2<br />

Sample by Field <strong>of</strong> Study<br />

Others<br />

<strong>Education</strong><br />

Arts / Humanities<br />

Health / Medicine<br />

IT<br />

Engineering<br />

Accounting / Finance<br />

Business<br />

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450 500<br />

26<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 2.3 Sample by Age Cohort shows the sample by age b<strong>and</strong>. It was deemed most appropriate<br />

to have a minimum age cell <strong>of</strong> 300 in order to provide a comparative measure by age b<strong>and</strong>. The<br />

largest sample group is for those aged 31 or over at 982. This is followed by the age b<strong>and</strong> 27 to 30<br />

years <strong>of</strong> age (635) <strong>and</strong> up to 26 years <strong>of</strong> age (302). Twenty-one participants did not answer this<br />

question.<br />

Chart 2.3<br />

Sample by Age Cohort<br />

1,200<br />

1,000<br />

800<br />

600<br />

400<br />

200<br />

0<br />

Up to 26 27 - 30 31 or more<br />

Chart 2.4 Sample by Gender shows the sample by gender with male participants constituting 1,012<br />

<strong>and</strong> female participants constituting 919. Nine participants did not answer this question.<br />

Chart 2.4<br />

Sample by Gender<br />

Male<br />

Female<br />

919<br />

1,012<br />

27<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

When evaluating the results there are several additional sample considerations to take into account<br />

<br />

<br />

21.5% <strong>of</strong> the total sample (417 participants) currently reside in Australia<br />

27.9% <strong>of</strong> the total sample (541 participants) are Australian permanent residents<br />

the peak graduation years <strong>of</strong> the total sample are 2005 (15.9%), 2004 (14.5%), 2003 (11.7%),<br />

2001 (10.0%) <strong>and</strong> 2002 (9.2%).<br />

Scholarships<br />

Of the total sample, 302 graduates (15.6%) received a scholarship to study in Australia with the<br />

largest group being those in the 31 years <strong>and</strong> over cohort; 21.4% <strong>of</strong> this cohort had a scholarship to<br />

study in Australia compared to 9% for the other two cohorts.<br />

Across the total sample<br />

5.3% were recipients <strong>of</strong> a scholarship from their home country<br />

4.9% were recipients <strong>of</strong> an AusAid scholarship<br />

3% were recipients <strong>of</strong> a university scholarship<br />

scholarship recipients were most likely to be studying in the fields <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (17.4% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Education</strong> sample), Science (12.5%) <strong>and</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> Medicine (9.2%).<br />

Currently Studying<br />

Across the total sample, 211 graduates (10.9% <strong>of</strong> the total sample) were studying at the time <strong>of</strong><br />

completing the survey. Of those currently studying<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

16.4% had graduated in Health <strong>and</strong> Medicine, followed by Arts <strong>and</strong> Humanities (15.3%) <strong>and</strong><br />

Accounting <strong>and</strong> Finance (14.3%)<br />

14.9% <strong>of</strong> all aged 26 or less were studying, compared to 10% for the other two age cohorts<br />

across each <strong>of</strong> the nationality groups the largest sample by nationality currently studying hail<br />

from Hong Kong (20.9%) <strong>and</strong> China (15.4%); 12.9% <strong>of</strong> graduates who now cite their nationality<br />

as Australian are currently studying <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> those currently located in Australia 14.4% are<br />

studying compared to 9.9% <strong>of</strong> those located <strong>of</strong>fshore<br />

38.9% <strong>of</strong> the sample who are currently studying are undertaking their program in Australia.<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong> Study<br />

This line <strong>of</strong> enquiry was to determine how long graduates studied in Australia <strong>and</strong> to determine<br />

whether there were any patterns by nationality or field <strong>of</strong> study.<br />

28<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Chart 2.5 Duration <strong>of</strong> Study by Nationality shows the shortest duration market is India, with 41%<br />

<strong>of</strong> graduates having only studied in Australia for up to 18 months. Australian higher education<br />

enrolments from India are mostly masters degrees by coursework.<br />

In contrast the longest duration markets are Hong Kong, China <strong>and</strong> Indonesia, with 56.1% <strong>of</strong><br />

graduates from Hong Kong, 43.1% from China <strong>and</strong> 42.6% <strong>of</strong> graduates from Indonesia having<br />

studied in Australia for four years or more.<br />

Chart 2.5<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong> Study by Nationality<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Malaysia Indonesia Singapore HK India China Thail<strong>and</strong> Others<br />

4 years or more<br />

3 years<br />

2 years<br />

Up to 18 months<br />

Further<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

27.7% <strong>of</strong> graduates from India studied in Australia for three years or more, compared with<br />

63.1% <strong>of</strong> graduates from China<br />

Engineering graduates reported the longest period <strong>of</strong> duration in Australia.<br />

39.1% <strong>of</strong> Thai graduates studied in Australia for two years.<br />

Interestingly 43.2% <strong>of</strong> graduates who now cite their nationality as Australian studied in Australia for<br />

five years or more.<br />

Where Are They Now?<br />

Australia, like many OECD countries, has developed migration policies <strong>and</strong> a skilled migration<br />

program that aims to attract skilled workers. <strong>International</strong> graduates represent a valuable source <strong>of</strong><br />

skilled labour sought after by Australia’s labour market <strong>and</strong> the labour markets <strong>of</strong> other OECD<br />

countries. Recent policy initiatives have transformed international graduates into a readily available<br />

source <strong>of</strong> skilled labour. Australia’s international education program is becoming increasingly<br />

enmeshed in Australia’s broader migration program.<br />

When asked what respondents wanted to do on completion <strong>of</strong> their studies, 19% said they aspired<br />

to live in Australia temporarily while 38% sought to stay permanently.<br />

29<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

At the time <strong>of</strong> the survey 21.5% were actually residing in Australia <strong>and</strong> 28% had gained residency.<br />

This is consistent with other comparative data.<br />

In Australia in 2005, 125,249 international students across all sectors finished studying, Of these<br />

125,249 students, 56,842 were higher education students 20 . In 2005/06, 23,205 students on student<br />

visas applied for migration, 15,767 <strong>of</strong> these were on higher education visas 21 . This tells us that in<br />

2005/06 19% <strong>of</strong> all finishing international students across all sectors applied for skilled migration.<br />

For international students finishing higher education the figure was higher at 28%.<br />

But the settlement <strong>of</strong> international graduates is not necessarily permanent. Whilst 28% had gained<br />

residency in our survey, a further 32% had a right to work in Australia. Amongst our respondents<br />

temporary migration is more prevalent than permanent migration as in Chart 2.6 Residential Status<br />

by Nationality.<br />

Chart 2.6<br />

Residential Status by Nationality<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

% who reside in Australia<br />

% who have an Australian working visa<br />

% who have Australian permanent residency<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Malaysia Indonesia Singapore Hong Kong India China Thail<strong>and</strong> Norway UK Other<br />

Countries<br />

Contrary to popular perception, the proportion <strong>of</strong> international students in Australian universities is in<br />

line with the proportion <strong>of</strong> people <strong>of</strong> overseas background in the Australian community. In Chapter 4<br />

Impact on Providers we see that in 2006, 18% <strong>of</strong> students in onshore higher education in Australia<br />

were international students <strong>and</strong> a further 12% <strong>of</strong> students were Australians who speak a language<br />

other than English at home 22 . This compares with figures from the 2006 Australian census which<br />

show that 22.2% <strong>of</strong> Australian residents were born overseas <strong>and</strong> that a further 21.5% spoke a<br />

language other than English at home 23 .<br />

20Australian <strong>Education</strong> <strong>International</strong> 2005<br />

21 Department <strong>of</strong> Immigration <strong>and</strong> Citizenship 2008<br />

22Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>, Employment <strong>and</strong> Workplace Relations 2007<br />

23Australian Bureau <strong>of</strong> Statistics 2006<br />

30<br />

Chapter 2 | <strong>IDP</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Pty Ltd

Our study found that <strong>of</strong> the total sample 28% had gained permanent residency. Chart 2.7<br />

Australian Permanent Residents by Nationality shows the proportion <strong>of</strong> graduates from our study<br />

who have gained residency.<br />

Chart 2.7<br />

Australian Permanent Residents by Nationality<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

%who haveAustralian permanentresidency<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Malaysia Indonesia Singapore Hong Kong India China Thail<strong>and</strong> Norway UK Other<br />

Countries<br />

When considering those who have working visas, those with permanent residence <strong>and</strong> those who<br />

are actually living in Australia some patterns emerge by nationality, field <strong>of</strong> study <strong>and</strong> age cohort<br />

graduates from China <strong>and</strong> India are more likely to have a working visa (66.2% <strong>and</strong> 58.4%,<br />

respectively), to have permanent residency (60% <strong>and</strong> 44.6%, respectively) <strong>and</strong> actually live in<br />

Australia (50.8% <strong>and</strong> 44.6%, respectively) compared to graduates from other nations<br />

<br />

<br />

graduates in Information Technology <strong>and</strong> Engineering are more likely to have a working visa<br />

(53.2% <strong>and</strong> 40%, respectively), to have permanent residency (47.4% <strong>and</strong> 36.9%, respectively)<br />

<strong>and</strong> actually live in Australia (39.2% <strong>and</strong> 29.3%, respectively) compared to graduates from other<br />

disciplines<br />

graduates aged 26 years or less are more likely to have a working visa (44%), to have<br />

permanent residency (36.8%) <strong>and</strong> actually live in Australia (34.1%) compared to other age<br />

cohorts.<br />

There are some exceptions<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

41.9% <strong>of</strong> graduates in <strong>Education</strong> have an Australian working visa<br />