Survey Research Types of Surveys Surveys are classified according ...

Survey Research Types of Surveys Surveys are classified according ...

Survey Research Types of Surveys Surveys are classified according ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

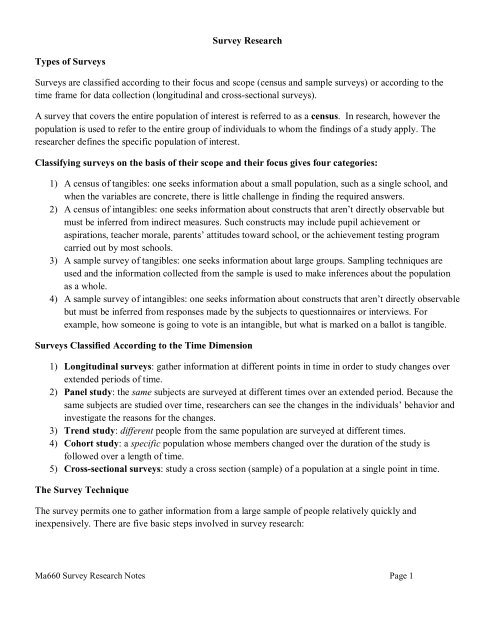

<strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

<strong>Types</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Survey</strong>s<br />

<strong>Survey</strong>s <strong>are</strong> <strong>classified</strong> <strong>according</strong> to their focus and scope (census and sample surveys) or <strong>according</strong> to the<br />

time frame for data collection (longitudinal and cross-sectional surveys).<br />

A survey that covers the entire population <strong>of</strong> interest is referred to as a census. In research, however the<br />

population is used to refer to the entire group <strong>of</strong> individuals to whom the findings <strong>of</strong> a study apply. The<br />

researcher defines the specific population <strong>of</strong> interest.<br />

Classifying surveys on the basis <strong>of</strong> their scope and their focus gives four categories:<br />

1) A census <strong>of</strong> tangibles: one seeks information about a small population, such as a single school, and<br />

when the variables <strong>are</strong> concrete, there is little challenge in finding the required answers.<br />

2) A census <strong>of</strong> intangibles: one seeks information about constructs that <strong>are</strong>n’t directly observable but<br />

must be inferred from indirect measures. Such constructs may include pupil achievement or<br />

aspirations, teacher morale, p<strong>are</strong>nts’ attitudes toward school, or the achievement testing program<br />

carried out by most schools.<br />

3) A sample survey <strong>of</strong> tangibles: one seeks information about large groups. Sampling techniques <strong>are</strong><br />

used and the information collected from the sample is used to make inferences about the population<br />

as a whole.<br />

4) A sample survey <strong>of</strong> intangibles: one seeks information about constructs that <strong>are</strong>n’t directly observable<br />

but must be inferred from responses made by the subjects to questionnaires or interviews. For<br />

example, how someone is going to vote is an intangible, but what is marked on a ballot is tangible.<br />

<strong>Survey</strong>s Classified According to the Time Dimension<br />

1) Longitudinal surveys: gather information at different points in time in order to study changes over<br />

extended periods <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

2) Panel study: the same subjects <strong>are</strong> surveyed at different times over an extended period. Because the<br />

same subjects <strong>are</strong> studied over time, researchers can see the changes in the individuals’ behavior and<br />

investigate the reasons for the changes.<br />

3) Trend study: different people from the same population <strong>are</strong> surveyed at different times.<br />

4) Cohort study: a specific population whose members changed over the duration <strong>of</strong> the study is<br />

followed over a length <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

5) Cross-sectional surveys: study a cross section (sample) <strong>of</strong> a population at a single point in time.<br />

The <strong>Survey</strong> Technique<br />

The survey permits one to gather information from a large sample <strong>of</strong> people relatively quickly and<br />

inexpensively. There <strong>are</strong> five basic steps involved in survey research:<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 1

1) Planning: <strong>Survey</strong> research begins with a question that the researcher believes can be answered most<br />

appropriately by means <strong>of</strong> the survey method. The researcher needs to decide on the data-gathering<br />

technique that will be used.<br />

2) Sampling: The researcher must make decisions about the sampling procedure that will be used and<br />

the size <strong>of</strong> the sample to survey. If one is to generalize the sample findings to the population, it is<br />

essential that the sample selected be representative <strong>of</strong> that population.<br />

3) Constructing the instrument: A major task in survey research is the construction <strong>of</strong> the instrument<br />

that will be used to gather the data from the sample.<br />

4) Conducting the survey: Once the data-gathering instrument is prep<strong>are</strong>d, it must be field-tested to<br />

determine if it will be provide the desired data. Also included in this step would be training <strong>of</strong> the<br />

users <strong>of</strong> the instrument, interviewing subjects or distributing questionnaires to them, and verifying the<br />

accuracy <strong>of</strong> the data gathered.<br />

5) Processing the data: The last step includes coding the data, statistical analysis, interpreting the<br />

results, and reporting the findings.<br />

Data Gathering Techniques<br />

There <strong>are</strong> two basic ways in which data <strong>are</strong> gathered in a survey research: interviews and questionnaires.<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> these has two options, thus providing four different approaches to collecting data:<br />

1) Personal interview: the interviewer reads the questions to the respondent in a face-to-face setting<br />

and records the answers.<br />

Advantages <strong>of</strong> personal interviews:<br />

a. Flexibility: The interviewer has the opportunity to observe the subject and the total situation<br />

in which he or she is responding. Questions can be repeated or their meanings explained in<br />

case they <strong>are</strong> not understood by the respondent(s). The interview can also press for additional<br />

information when a response seems incomplete or not entirely relevant.<br />

b. Greater Response Rate: Response rate refers to the proportion <strong>of</strong> the selected sample that<br />

agrees to be interviewed or returns a completed questionnaire. Personal contact increases the<br />

likelihood that the individual will participate and will provide the desired information.<br />

Furthermore, the interviewer is able to obtain an answer to all or most <strong>of</strong> the questions.<br />

c. Interviewer Control <strong>of</strong> Question Order: The interviewer has control over the order with which<br />

questions <strong>are</strong> considered. In some cases, it is very important that respondents not know the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> later questions because their responses to these questions might influence earlier<br />

responses. This problem is eliminated in an interview, where the subject does not know what<br />

questions <strong>are</strong> coming up and cannot go back and change answers previously given. For<br />

individuals who cannot read and understand a written questionnaire, interviews provide the<br />

only possible information-gathering technique.<br />

Disadvantages <strong>of</strong> personal interviews:<br />

a. Cost: Personal interviews <strong>are</strong> more costly than other survey methods. The selection and<br />

training <strong>of</strong> the interviewers and their travel to the interview site make the procedure costly. It<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 2

takes a great deal <strong>of</strong> time to contact potential respondents, set up appointments, and actually<br />

conduct the interview.<br />

b. Possibility <strong>of</strong> Interviewer Bias: Interviewer bias occurs when the interviewer’s own feelings<br />

and attitudes or the interview’s gender, race, and other characteristics influence the way in<br />

which the questions <strong>are</strong> asked or interpreted. The interviewer may verbally or nonverbally<br />

encourage or reward “correct” responses that fit his or her expectations.<br />

c. Social Desirability Bias: Social desirability bias occurs when the respondents want to please<br />

the interviewer by giving socially acceptable responses that they would not necessarily give<br />

on an anonymous questionnaire.<br />

2) Telephone interview: The telephone interview has become more popular and comp<strong>are</strong>s favorably<br />

with face-to-face interviewing.<br />

Advantages <strong>of</strong> telephone interviews:<br />

a. Lower Cost and Faster Completion with Relatively High Response Rates: Telephone<br />

interviews can be conducted over a relatively short time span with persons scattered over a large<br />

geographic <strong>are</strong>a. The phone permits the survey to reach people who would not open their doors to<br />

an interviewer, but who would not open their doors to an interviewer, but who might be willing to<br />

talk on the telephone.<br />

b. Respondent Anonymity: Respondents have a greater feeling <strong>of</strong> anonymity—hence there may be<br />

less interviewer bias and less social desirability bias than is found with personal interviews.<br />

c. Computer Usage: Computers can be used in administering the interview and in coding the<br />

responses. Wearing earphones, the interviewer can sit at a computer while it randomly selects a<br />

telephone number and dials. When the respondent answers, the interviewer reads the questions<br />

that appear on screen and types the answers directly into the computer. This saves the researcher<br />

time usually spent in coding, getting the data organized, and entering it into the computer for<br />

analysis.<br />

Disadvantages <strong>of</strong> telephone interviews:<br />

a. Less Opportunity for Establishing Rapport with the Respondent: It takes a great deal <strong>of</strong> skill<br />

to carry out a telephone interview so that valid results <strong>are</strong> obtained. It is <strong>of</strong>ten difficult to<br />

overcome the suspicions <strong>of</strong> the surprised respondents, especially when personal or sensitive<br />

questions <strong>are</strong> asked. An advance letter that informs the potential respondents <strong>of</strong> the approaching<br />

call is sometimes used to deal with this problem, but the letter can induce another problem. The<br />

recipient has time to think about responses or to prep<strong>are</strong> a refusal to participate when the call<br />

comes.<br />

b. <strong>Survey</strong> Exclusion: Households without telephones and those with unlisted numbers <strong>are</strong><br />

automatically excluded from the survey, which may bias results. There is, however, a technique<br />

known as random digit dialing that solves the problem <strong>of</strong> unlisted numbers (although it does not<br />

help to reach the households without a telephone).<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 3

3) Mailed questionnaire: Often much <strong>of</strong> the same information can be obtained by means <strong>of</strong> a<br />

questionnaire that is mailed to each individual in the sample, with a request that it be completed and<br />

returned at a given date. Because the questionnaire is mailed, it is possible to include a larger number<br />

<strong>of</strong> subjects as well as subjects in more diverse locations than is practical with the interview.<br />

Advantages <strong>of</strong> mailed questionnaires:<br />

a. Confidentiality or Anonymity: A mailed questionnaire guarantees confidentiality or anonymity,<br />

thus perhaps eliciting more truthful responses than would be obtained with a personal interview.<br />

b. No Interview Bias: The mailed questionnaire eliminates the problem <strong>of</strong> interviewer bias.<br />

Disadvantages <strong>of</strong> mailed questionnaires:<br />

a. Possibility <strong>of</strong> Question Misinterpretation: It is difficult to formulate a series <strong>of</strong> questions whose<br />

meanings <strong>are</strong> crystal-clear to every reader. The investigator may know exactly what is meant by a<br />

question, but the respondent may interpret question differently.<br />

b. Low Return Rate: It is easy for the individual who receives a questionnaire to lay it aside and<br />

simply forget to complete and return it. A low response rate limits the generalizability <strong>of</strong> the<br />

results <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire study. Factors that have been found to influence the rate <strong>of</strong> returns for<br />

a mailed questionnaire <strong>are</strong>:<br />

1) the length <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire<br />

2) the cover letter<br />

3) the sponsorship <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire<br />

4) the attractiveness <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire<br />

5) the ease <strong>of</strong> completing it and mailing it back<br />

6) the interest aroused by the content<br />

7) the use <strong>of</strong> a monetary incentive<br />

8) the follow-up procedures<br />

4) Directly-administered questionnaire: This questionnaire is administered to a group <strong>of</strong> people at a<br />

certain place for a specific purpose. Examples include surveying the freshmen or their p<strong>are</strong>nts<br />

attending summer orientation at a university.<br />

Advantages <strong>of</strong> directly-administered questionnaire:<br />

a. High Response Rate: The response typically reaches 100 percent.<br />

b. Low Cost<br />

c. <strong>Research</strong>er Availability: <strong>Research</strong>er is present to provide assistance or answer questions.<br />

Disadvantages <strong>of</strong> directly-administered questionnaire:<br />

a. <strong>Research</strong>er is restricted in terms <strong>of</strong> where and when the questionnaire can be administered.<br />

b. Because the sample is usually quite specific, the findings <strong>are</strong> generalizable only to the population<br />

that the sample represents.<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 4

Constructing the Instrument<br />

<strong>Types</strong> <strong>of</strong> Questions: Because survey data consist <strong>of</strong> peoples’ responses to questions, it is very important to<br />

start with good questions. Two basic types <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>are</strong> used in survey instruments:<br />

1) Closed-ended Questions: One uses closed-ended questions when all <strong>of</strong> the possible, relevant<br />

responses to a question can be specified and the number <strong>of</strong> possible responses is limited.<br />

Advantages:<br />

a. Responses <strong>are</strong> easier to tabulate.<br />

b. Responses can be coded directly on scannable sheets that can be “read” and the data put into a<br />

computer for analysis.<br />

c. Respondents can be answered more easily and quickly.<br />

d. Ensures that all subjects will have the same frame <strong>of</strong> reference in responding and may also make<br />

it easier for subjects to respond to questions dealing with topics <strong>of</strong> a sensitive or private nature.<br />

Disadvantages:<br />

a. Take more time to construct.<br />

b. Do not provide more insight into whether respondents really have information or any clearly<br />

formulated opinions about an issue.<br />

c. Easier for the uninformed respondent to choose one <strong>of</strong> the suggested answers than to admit to<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge on an issue.<br />

d. Respondents who have the knowledge or who have well-informed opinions on the issue may<br />

dislike being restricted to simple response categories that do not permit them to qualify their<br />

answers.<br />

2) Open-ended questions <strong>are</strong> used when there <strong>are</strong> a great number <strong>of</strong> possible answers or when the<br />

researcher is not able to predict all the possible answers.<br />

Advantages:<br />

a. Permit a free response rather than restricting the respondent to a choice from among stated<br />

alternatives.<br />

b. Individuals <strong>are</strong> free to respond from their own frame <strong>of</strong> reference, thus providing a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

responses.<br />

c. Easier to construct<br />

Disadvantages:<br />

a. Tedious analysis and time-consuming as the researcher must read and interpret each response,<br />

then develop a coding system that will make possible a quantitative analysis <strong>of</strong> the responses.<br />

b. Some responses may be unclear, and the researcher is unsure how to classify or code the<br />

response.<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 5

Writing <strong>Survey</strong> Questions<br />

Before beginning to write a structured set <strong>of</strong> survey questions, it can be helpful to have focus groups discuss<br />

the questions in a nonstructured form. A moderator keeps the discussions focused on a preset agenda and<br />

asks questions to clarify comments. Focus group discussions help the researcher understand how people talk<br />

about the survey issues, which is helpful in choosing vocabulary and in phrasing questions. Focus groups<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten can suggest issues, concerns, or points <strong>of</strong> view about the topic that the researcher has not considered.<br />

Characteristics <strong>of</strong> a Good Questionnaire:<br />

1) It deals with a significant topic, one the respondent will recognize as important enough to warrant<br />

spending one’s time on. The significance should be clearly and c<strong>are</strong>fully stated on the questionnaire<br />

or in the letter that accompanies it.<br />

2) It only seeks information that cannot be obtained from other sources such as school reports or census<br />

data.<br />

3) It is as short as possible and only long enough to get the essential data. Long questionnaires<br />

frequently find their way into the wastebasket.<br />

4) It is attractive in appearance, neatly arranged, and clearly duplicated or printed.<br />

5) Directions <strong>are</strong> clear and complete. Important terms <strong>are</strong> defined. Each question deals with a single idea<br />

and is worded as simply and clearly as possible.<br />

6) The questions <strong>are</strong> objective with no leading suggestions as to the responses desired.<br />

7) Questions <strong>are</strong> presented in good psychological order, proceeding from general to more specific<br />

responses. The order helps respondents to organize their own thinking so that their answers <strong>are</strong><br />

logical and objective.<br />

8) It is easy to tabulate and interpret.<br />

Preparing the Cover Letter<br />

<strong>Research</strong>ers may find it useful to mail an introductory letter to potential respondents in advance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

questionnaire itself. This procedure alerts the subject to the study so that he/she is not overwhelmed by the<br />

questionnaire package. In any case, a cover letter addressed to the respondent by name and title must<br />

accompany the questionnaire. The cover letter should be as brief as possible. One page is the maximum<br />

recommended length. Enclose the letter in an envelope along with the questionnaire. Always include a selfaddressed,<br />

stamped return envelope for the respondent’s use. This is indispensable for a good return rate.<br />

Token monetary incentive increases response rate; however, <strong>of</strong>fering a payment isn’t always possible<br />

because a token amount can greatly increase the cost <strong>of</strong> the survey if the sample is large.<br />

The cover letter introduces the potential respondents to the questionnaire and “sells” them on responding.<br />

The cover letter should include the following elements:<br />

1) The Purpose <strong>of</strong> the Study: The first paragraph should explain the purpose <strong>of</strong> the study and its<br />

potential usefulness. It will be helpful to relate the importance <strong>of</strong> the study to a reference group with<br />

which the individuals may identify.<br />

2) A Request for Cooperation: The letter should explain why the potential respondent was included in<br />

the sample and should make an appeal for the respondent’s cooperation. Respondents should be made<br />

to feel that they can make an important contribution to the study.<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 6

3) The Protection Provided the Respondent: The letter must not only assure the respondents that their<br />

responses will be confidential but must also explain how that confidentiality will be maintained.<br />

<strong>Research</strong>ers may use an identification coding system.<br />

4) Sponsorship <strong>of</strong> the Study: The signature on the letter is important in influencing the return <strong>of</strong> the<br />

questionnaire. If the study is part <strong>of</strong> a doctoral dissertation, it would be helpful if a person well<br />

known to the respondents, such as the head <strong>of</strong> a university department or the dean <strong>of</strong> the school, signs<br />

or countersigns the letter. Such a signature is likely to be more effective than that <strong>of</strong> an unknown<br />

graduate student.<br />

5) Promise <strong>of</strong> Results: An <strong>of</strong>fer may be made to sh<strong>are</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> the study with the respondents if<br />

they <strong>are</strong> interested. They should be told how to make the request for the results known to the<br />

researcher.<br />

6) Appreciation: An expression <strong>of</strong> appreciation for their assistance and cooperation with the study<br />

should be included.<br />

7) Recent Data on the Letter: The cover letter should be dated near the day <strong>of</strong> mailing. A potential<br />

respondent will not be impressed by a letter dated several weeks before receipt.<br />

8) Request for Immediate Return: Urge immediate return <strong>of</strong> the questionnaire. A questionnaire that<br />

fails to receive attention within a week is not likely ever to be returned.<br />

In order to reach the maximum percentage <strong>of</strong> returns in a mailed questionnaire survey, planned follow-up<br />

mailings <strong>are</strong> essential. First follow-up having both a letter and a replacement questionnaire should occur in<br />

about 7-10 days after the initial mailing; second follow-up in about 3 weeks, and third follow-up in about 6<br />

to 7 weeks. It is suggested that the researcher include in the third follow-up a postcard on which subjects<br />

could indicate that they do not wish to participate in the survey and will not be returning the questionnaire.<br />

Such a procedure permits definite identification <strong>of</strong> nonrespondents.<br />

Ma660 <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Notes Page 7