Dispute Settlement under COMESA - Paul Roos Gymnasium

Dispute Settlement under COMESA - Paul Roos Gymnasium

Dispute Settlement under COMESA - Paul Roos Gymnasium

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Dispute</strong> <strong>Settlement</strong> <strong>under</strong><br />

<strong>COMESA</strong><br />

By<br />

Felix Maonera<br />

tralac Working Paper<br />

No 7<br />

October 2005

Abstract<br />

The <strong>COMESA</strong> Court of Justice, established in 1994 <strong>under</strong><br />

Article 7 of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Treaty, became operational in 1998.<br />

The Judges of the Court were appointed at the Third <strong>COMESA</strong><br />

Summit on 30 June 1998 at Kinshasa in the Democratic<br />

Republic of Congo. The Court was to be temporarily hosted<br />

within the <strong>COMESA</strong> Secretariat from 1998, and in March 2003,<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> decided that the seat of the Court be moved to<br />

Khartoum, in the Republic of Sudan. However, the Court has to<br />

date remained in Lusaka, Zambia. Although the Court is an<br />

integral part of the <strong>COMESA</strong> integration process, little appears<br />

to be known about it. This paper seeks to give a brief overview<br />

of the Court, its jurisdiction, and how it works, against the<br />

background of some cases that it has adjudicated upon.

Table of Contents<br />

Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 0<br />

1 Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1<br />

2 The judges, jurisdiction and the competent parties ............................................. 3<br />

3 Agents, lawyers, experts and costs ................................................................... 10<br />

4 Some decided cases ......................................................................................... 13<br />

5 Some concluding thoughts ................................................................................ 19<br />

References ............................................................................................................... 21<br />

List of cases filed, disposed of and pending 22<br />

www.tralac.org

Abbreviations<br />

Authority<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong><br />

PTA<br />

The Council<br />

The Court<br />

The President<br />

The Treaty<br />

The supreme policy organ of <strong>COMESA</strong>, made up of the Heads of<br />

State and Government<br />

Common Market for East and Southern Africa<br />

Preferential Trade Area<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> Council of Ministers<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> Court of Justice<br />

The Judge who is President of the Court<br />

Treaty Establishing the Common Market of East and Southern<br />

Africa, 1994<br />

0

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

1 Introduction<br />

The Common Market for East and Southern Africa (<strong>COMESA</strong>), a grouping of<br />

nineteen countries, 1 in 1994 replaced the former Preferential Trade Area (PTA) which<br />

had existed from 1981. <strong>COMESA</strong> was established as an organization of free,<br />

independent, sovereign states which agreed to cooperate in developing their natural<br />

and human resources for the good of all their people. Its main focus is on the<br />

formation of a large economic and trading unit that is capable of overcoming some of<br />

the barriers that are faced by individual states.<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> has a decision making structure at the head of which is the Authority, the<br />

supreme policy organ of <strong>COMESA</strong>, made up of the Heads of State and Government<br />

of all the member countries; a Council of Ministers responsible for policy making;<br />

technical committees and a number of other advisory bodies. Several institutions,<br />

which include a Court of Justice (the Court), have been created to promote subregional<br />

cooperation and development. Overall co-ordination of the activities of<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> is the responsibility of the Secretariat, based in Lusaka, Zambia.<br />

The Court was established in 1994 <strong>under</strong> Article 7 of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Treaty, and<br />

became operational in 1998. The Judges of the Court were appointed by the<br />

Authority during the Third <strong>COMESA</strong> Summit on 30 June 1998 at Kinshasa in the<br />

Democratic Republic of Congo. The Registrar of the Court was then appointed by the<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> Council of Ministers (the Council), during its meeting in June 1998, also at<br />

Kinshasa. The Court was to be temporarily hosted within the <strong>COMESA</strong> Secretariat<br />

from 1998. In March 2003, the Authority decided that the seat of the Court should be<br />

in Khartoum, in the Republic of Sudan, but due to some technical difficulties, the<br />

Court has to date remained in Lusaka, Zambia. To ensure the independence of the<br />

Court, Article 9 (2) (c) of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Treaty provides that the Council shall give<br />

directions to all subordinate organs of <strong>COMESA</strong> other than the Court.<br />

1 As shown on the <strong>COMESA</strong> website, http://www.comesa.int/countries/, last visited on 27/07/2005, the<br />

countries are Angola, Burundi, Comoros, D.R. Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya,<br />

Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sudan, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, and<br />

Zimbabwe.<br />

1

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

In addition to its other responsibilities, the Court took over the responsibilities of three<br />

other judicial organs that had existed <strong>under</strong> the PTA. One of these was the PTA<br />

Tribunal, whose function had been to ensure the proper interpretation of the<br />

provisions of the PTA Treaty and to adjudicate only in disputes between Member<br />

States, arising from the interpretation and application of the PTA Treaty. The<br />

jurisdiction of the Tribunal had been narrow and its ad hoc nature and lack of a<br />

separate budget were thought to stifle its development. The second PTA judicial<br />

organ whose responsibility the court took over was the PTA Administrative Appeals<br />

Board, whose jurisdiction <strong>under</strong> the PTA Treaty had been to adjudicate in disputes<br />

between the PTA and its staff, arising from the interpretation and application of the<br />

Treaty, Staff Rules and Regulations and terms and conditions of contracts of<br />

employment of the staff. The ad hoc status of the Board, its lack of an independent<br />

Registry and separate budget, in some instances, adversely affected the functioning<br />

of this organ. The third judicial organ whose responsibilities were subsumed by the<br />

Court was the PTA Centre for Commercial Arbitration, which was responsible for<br />

facilitating international arbitration and the conciliation of private commercial<br />

disputes. The Centre had been based in Djibouti and had operated <strong>under</strong> the<br />

auspices of the PTA Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry.<br />

The establishment of the Court was considered a major event in the history of<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> as an organization, and in the development of the <strong>COMESA</strong> community<br />

law and jurisprudence. <strong>COMESA</strong> pursues its aims exclusively through a body of law<br />

which is independent, separate from and yet superior to national law. The Court of<br />

Justice, as the judicial organ of the Common Market, is the backbone of that legal<br />

system. Its Judges are supposed to ensure that the law is not interpreted and applied<br />

differently in each Member State, and that as a shared legal system, it remains a<br />

Common Market 2 system that is uniformly applied.<br />

2 A ‘common market’ can be described as a group of countries that guarantee the free movement of<br />

goods, services and factors (labour and capital) produced within the group and the removal of all<br />

tariffs and non-tariff barriers between themselves. The Member countries also agree to levy a common<br />

external tariff on imports from outside the group. A common market is thus equivalent to, but also goes<br />

beyond a customs union, by allowing for the free movement of factors among the Members of the<br />

group. <strong>COMESA</strong> was notified to the WTO <strong>under</strong> the Enabling Clause on 29 June 1995.<br />

2

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

The Registrar is responsible for the day to day administration of the business of the<br />

Court <strong>under</strong> the supervision of the Judge President. The Court employs such other<br />

staff as are required to enable it to perform its functions, and its budget is borne by<br />

the Member States. The official languages of the Court are English, French and<br />

Portuguese.<br />

2 The judges, jurisdiction and the competent parties<br />

The Court is composed of seven Judges appointed by the Authority, with one of<br />

these judges appointed as the President of the Court. 3 Upon the request of the court,<br />

additional judges may be appointed. The President directs the judicial business and<br />

the administration of the Court and, unless he designates another Judge to do so,<br />

presides at its hearings and deliberations. The Judges of the Court are chosen from<br />

among persons of impartiality and independence, who fulfil the conditions required<br />

for the holding of high judicial office in their respective countries of domicile, or who<br />

are jurists of recognized competence. No two or more Judges of the Court can at any<br />

time be nationals of the same country.<br />

The Judges hold office for a period of five years, and are eligible for re-appointment<br />

for a further period of five years. They hold office throughout the term of their<br />

respective appointments unless they resign or die, or are removed from office in<br />

accordance with the provisions of the Treaty. The President of the Court or a Judge<br />

may not be removed from office except by the Authority for stated misbehaviour, or<br />

for inability to perform the functions of his office due to infirmity of mind or body. The<br />

President and the Judges are immune from legal action for any act or omission<br />

committed in the discharge of their functions <strong>under</strong> the Treaty.<br />

A Judge may, at any time, resign from office by letter delivered to the President of the<br />

Court for transmission to the Chairman of the Authority, and his resignation will take<br />

effect on the date it has been accepted by the Authority. However, where the term of<br />

office of a Judge comes to an end, or where a Judge resigns before a decision or<br />

3 At the time of publishing, it was not possible to ascertain the names of the current and former judges<br />

and their nationalities<br />

3

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

opinion of the Court is delivered with respect to a matter which has been argued<br />

before the Court of which he was a member, such Judge shall, only for the purpose<br />

of completing that particular matter, continue to sit as a Judge. The Judge who is the<br />

President of the Court may at any time resign from office by giving one year's written<br />

notice to the Chairman of the Authority, but his resignation shall not take effect until<br />

his successor has been appointed by the Authority and has taken office.<br />

It is rather curious that a Judge who resigns before a decision or opinion of the Court<br />

has been delivered with respect to a matter which has been argued before the Court<br />

of which he was a member, indicating by so resigning that he wishes to take no<br />

further part in the work of the Court, is still expected to continue sitting as a Judge in<br />

that matter even just for the purpose of completing that particular matter. While the<br />

motive for compelling a Judge who has resigned to stay until the case is concluded,<br />

and in the case of the Judge President, until a replacement is found, is obviously for<br />

the sake of continuity, the workability of such compulsion is in doubt. It would seem<br />

that resignation is the clearest way of indicating one's wish to have nothing more to<br />

do with the work of the Court. Asking a Judge to stay on, most probably against<br />

his/her will, would not appear to be in the best interests of the Court. It is imaginable<br />

that a case in which the resigning Judge was participating, could take a while to<br />

conclude and that finding a replacement for a resigning Judge President could also<br />

take long. It remains unclear what would happen to a Judge (or Judge President)<br />

who refuses to stay on as required.<br />

The Court has jurisdiction to adjudicate upon all matters which may be referred to it<br />

pursuant to the Treaty 4 , and to hear disputes between the Common Market and its<br />

employees that arise out of the application and interpretation of the Staff Rules and<br />

Regulations of the Secretariat or the terms and conditions of employment of the<br />

4 Article 23 of the Treaty. The articles relating to the Court’s jurisdiction, like any other provision of the<br />

Treaty, remain binding on <strong>COMESA</strong> Members for as long as they remain party to the Treaty. In terms<br />

of Article 191 of the Treaty, any Member State may withdraw from the Common Market upon giving to<br />

the Secretary-General one year's written notice of its intention to withdraw, and will at the end of such<br />

year, if such notice is not withdrawn, cease to be a Member State of the Common Market. During the<br />

period of one year referred to, a Member State wishing to withdraw from the Common Market shall<br />

nevertheless observe the provisions of the Treaty and shall remain liable for the discharge of its<br />

obligations <strong>under</strong> the Treaty. The obligations assumed by the Member States <strong>under</strong> the Treaty shall,<br />

to the extent necessary, survive the termination of membership of any Member State.<br />

4

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

employees of the Common Market. 5 It also has jurisdiction to determine claims by<br />

any person against the Common Market or its institutions for acts of their servants or<br />

employees in the performance of their duties. 6 The Court’s jurisdiction also extends<br />

to hearing and determining any matter arising from an arbitration clause contained in<br />

a contract which confers such jurisdiction to which the Common Market or any of its<br />

institutions is a party, and to any matter arising from a dispute between the Member<br />

States regarding this Treaty if the dispute is submitted to it <strong>under</strong> a special<br />

agreement between the Member States concerned. 7 Except where the jurisdiction is<br />

conferred on the Court by or <strong>under</strong> the Treaty, disputes to which the Common Market<br />

is a party shall not on that ground alone be excluded from the jurisdiction of national<br />

courts. 8<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> Member States, the <strong>COMESA</strong> Secretary General, and legal and natural<br />

persons have locus standi to refer matters to the Court. A Member State that<br />

considers that another Member State, or the Council, has failed to fulfil an obligation<br />

<strong>under</strong> the Treaty or has infringed a provision of the Treaty, may refer the matter to<br />

the Court for determination. A Member State may also refer for determination by the<br />

Court, the legality of any act, regulation, directive or decision of the Council on the<br />

grounds that such act, regulation, directive or decision is ultra vires (that is, goes<br />

beyond what the Treaty allows), or is unlawful, or is an infringement of the provisions<br />

of the Treaty or of any rule of law relating to its application, or amounts to a misuse or<br />

abuse of power. 9<br />

The <strong>COMESA</strong> Secretary General has the power to refer a matter to the Court, 10 but<br />

in a rather circuitous way. Where the Secretary-General considers that a Member<br />

State has failed to fulfil an obligation <strong>under</strong> the Treaty, or has infringed a provision of<br />

the Treaty, he can submit his findings to the Member State concerned to enable that<br />

Member State to submit its observations on the findings. If the Member State<br />

5 Article 27 of the Treaty.<br />

6 Article 27(2) of the Treaty.<br />

7 Article 28 of the Treaty.<br />

8 Article 29 of the Treaty.<br />

9 Article 24 of the Treaty.<br />

10 Article 25 of the Treaty.<br />

5

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

concerned does not submit its observations to the Secretary-General within two<br />

months, or if the observations submitted are unsatisfactory, the Secretary-General<br />

can refer the matter to the Bureau of the Council (composed of the Chairman, Vice-<br />

Chairman and Rapporteur) that will decide whether the matter should immediately be<br />

referred to the Court by the Secretary-General, or be referred to the Council. Where<br />

a matter has been referred to the Council and the Council fails to resolve the matter,<br />

the Council can direct the Secretary-General to refer the matter to the Court.<br />

It would appear that the Secretary General’s decision to refer a matter to the Court is<br />

not really his decision. The Bureau of the Council is the Secretary General’s first port<br />

of call if he feels a matter should be brought to the attention of the Court. It is the<br />

Bureau, not the Secretary General, that shall decide whether the matter should be<br />

referred to the Council. And it is the Council, not the Secretary General, that will<br />

direct that the matter be referred to the Court. No time limit is given for the Council,<br />

which meets only once a year immediately preceding a meeting of the Authority or in<br />

extraordinary sessions at the request of a Member State supported by at least one<br />

third of the Member States, to try and resolve the matter. No time limit is given as to<br />

how soon after failing to resolve the matter the Council shall direct the Secretary<br />

General to take the matter to the Court.<br />

Any person who is resident in a Member State may refer for determination by the<br />

Court the legality of any act, regulation, directive, or decision of the Council or of a<br />

Member State on the grounds that such act, directive, decision or regulation is<br />

unlawful, or is an infringement of the provisions of the Treaty. 11 However, where the<br />

matter for determination relates to any act, regulation, directive or decision by a<br />

Member State, such a person will not refer the matter for determination unless he<br />

has first exhausted local remedies in the national courts, or tribunals, of the Member<br />

State. It is clear that a person who can refer the case does not have to be a citizen of<br />

a Member State. Neither does he have to be a resident, or a citizen, of the country he<br />

is complaining against, since the Treaty states that a person who is resident in a<br />

Member State may refer for determination by the Court a matter involving a Member<br />

State. This means that a person who is not even a citizen, but only a resident of any<br />

11 Article 26 of the Treaty.<br />

6

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> Member State, can take a matter involving another Member State, in which<br />

he does not even reside, to the Court.<br />

The Court also has the jurisdiction to hear disputes between <strong>COMESA</strong> and its<br />

employees that arise out of the application and interpretation of the Staff Rules and<br />

Regulations of the Secretariat or the terms and conditions of employment of the<br />

employees of <strong>COMESA</strong>. The Court has jurisdiction to determine claims by any<br />

person against <strong>COMESA</strong> or its institutions for acts of their servants or employees in<br />

the performance of their duties. It also has jurisdiction to hear and determine any<br />

matter, arising from an arbitration clause contained in a contract which confers on the<br />

Court such jurisdiction, and to which <strong>COMESA</strong>, or any of its institutions, is a party. It<br />

can also adjudicate upon a dispute between the Member States regarding the Treaty,<br />

if the dispute is submitted to the Court by an agreement of the Member States<br />

concerned.<br />

Except where jurisdiction is conferred on the Court by or <strong>under</strong> the Treaty, disputes<br />

to which <strong>COMESA</strong> is a party will not, on that ground alone, be excluded from the<br />

jurisdiction of Members’ national courts. However, decisions of the Court on the<br />

interpretation of the provisions of the Treaty will have precedence over decisions of<br />

national courts. In other words, decisions of national courts that relate to the<br />

interpretation of any provision of the Treaty will be taken into account only where they<br />

agree with the decision, if any, arrived at by the Court or where the Court has not<br />

made any pronouncement on that provision. If the national court’s decision relating to<br />

the interpretation of any provision of the Treaty does not agree with a decision of the<br />

Court, then that national court’s decision shall be overridden by that of the Court.<br />

However, it is recognized that the national courts may find it necessary to make a<br />

decision relating to the interpretation of a provision of the Treaty. To avoid a situation<br />

where the national court’s decision could conflict with a decision the Court may<br />

make, where a question is raised before any court or tribunal of a Member State<br />

concerning the application or interpretation of the Treaty or the validity of the<br />

regulations, directives and decisions of <strong>COMESA</strong>, such court or tribunal is expected,<br />

if it considers that a ruling on the question is necessary to enable it to give judgment,<br />

to request the Court to give a preliminary ruling.<br />

7

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

The Court is to consider and determine every case referred to it <strong>under</strong> the Treaty in<br />

accordance with the Rules of Court, which regulate the detailed conduct of business<br />

of the Court such as the organization of the court, the power of the President of the<br />

court, duties of the registrar, seat, sessions and sittings of the court, quorum and the<br />

manner in which the Judges conduct their deliberations. The Court’s sessions are<br />

open to the public, and the Court is expected to deliver its judgments in public<br />

sessions. But if the Court considers that, in special circumstances, it is not desirable<br />

that its judgment be delivered in public, the Court may deliver its judgment before the<br />

parties privately.<br />

The judgment, subject to the provisions of the Court’s rules as to review, will be final<br />

and conclusive, and is not open to appeal. 12 An application for revision of a judgment<br />

may be made to the Court only if it is based upon the discovery of some fact which<br />

by its nature might have had a decisive influence on the judgment if it had been<br />

known to the Court at the time the judgment was given, but which in fact, at that time,<br />

was unknown to both the Court and the party making the application, and which<br />

could not have been discovered by that party before the judgment was made. A<br />

revision may also be entertained if there was a mistake or error on the record. The<br />

Court will deliver only one judgment in respect of every matter before it, which will be<br />

the judgment of the Court, reached in private by majority verdict. In other words, no<br />

dissenting opinion from any other Judge can be delivered.<br />

The proceedings before the Court will be either written or oral, and every party to a<br />

matter before the Court is to be represented by Counsel appointed by that party.<br />

There is no provision, in either the Treaty or the Rules of Court, for the rendering of<br />

assistance to any party involved in the proceedings. It would appear that a party to a<br />

matter before the Court, who is himself a lawyer or an advocate, still has to be<br />

represented by Counsel since this requirement is expressed in mandatory terms. A<br />

Member State, the Secretary-General or a resident of a Member State who is not a<br />

12 It is not clear what the motivation behind the prohibition of an appeal was. However, it may have been<br />

the fact that, unlike in the case of domestic courts, the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court is the court of first instance and<br />

appeal all in one; in other words, any appeal would have to be heard by the same Court since there is<br />

no other Court, <strong>under</strong> the Treaty, higher than the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court. While it could be envisaged that<br />

judges different from those that passed the initial judgment could be assigned to hear the appeal, it<br />

may be that Members did not want a situation whereby the Court system would be clogged by such<br />

appeals at the expense of new cases.<br />

8

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

party to a case before the Court may, with the permission of the Court, also<br />

participate in that case. However, the participation of that Member State, Secretary<br />

General or resident, will be limited to the submission of evidence supporting or<br />

opposing the arguments of a party to the case. 13<br />

The Court has the inherent power to make such orders as may be necessary to meet<br />

the ends of justice or to prevent the abuse of the process of the Court. A Member<br />

State, or the Council, is to take, without delay, 14 the measures required of it to<br />

implement a judgment of the Court. The Court may prescribe such sanctions or<br />

penalties as it considers necessary against a party who defaults in implementing the<br />

decisions of the Court. The execution of a judgment of the Court, which imposes a<br />

pecuniary obligation on a person, will be governed by the rules of civil procedure in<br />

force in the Member State in which execution is to take place. Since the rules of civil<br />

procedure may not be identical in all countries, it is possible that the speed with<br />

which judgments will be executed in the Members States will differ. 15<br />

The order for execution, which will be attached to the judgment of the Court, will<br />

require only the verification of the authenticity of the judgment by the Registrar before<br />

the party in whose favour execution is to take place can proceed to execution in<br />

accordance with the rules of civil procedure in force in that Member State. Although<br />

this is not clearly stated, it would appear that in the event of a dispute over a party’s<br />

compliance with a Court’s decision, the matter will be referred back to the Court,<br />

since it is stated that if the Court finds that a party has defaulted in implementing the<br />

Court's judgment, or otherwise defied it, the Court may impose a financial penalty on<br />

that party, to be paid to the Court. 16 When a judgment of the Court has been<br />

complied with, the Registrar will insert a note in the register to that effect against the<br />

record of the judgment. 17<br />

13 This does not appear to have happened as yet in practice, from a perusal of the cases decided so far<br />

and those pending.<br />

14 It is not clear from the Treaty who determines what constitutes ‘delay.’ Presumably, this will be<br />

determined by the Court if brought to its attention by the winning party.<br />

15 It was not possible, at the time of publication, to gather information regarding the enforcement of the<br />

Court’s rulings in the domestic sphere, i.e. the degree of difficulty, if any, victorious parties have faced<br />

when attempting to enforce the Court’s judgments.<br />

16 Rule 58 of the Rules of Court.<br />

17 A perusal of the decided cases indicates that it has taken the Court an average of between 9-12<br />

months to dispose of a case, which is quite efficient and is comparable for example to the time the<br />

9

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

The Court can assume the role of a court of arbitration in any matter arising from an<br />

arbitration clause contained in a contract to which <strong>COMESA</strong>, or any of its institutions,<br />

is a party and which confers jurisdiction on the Court to arbitrate. The Court can also<br />

arbitrate in a dispute between the Member States regarding the interpretation of the<br />

Treaty, if the Member States concerned agree to submit such matter to the Court. It<br />

would appear that in conducting the arbitration, the Court has wide discretion as<br />

regards what law to apply since it is stated that the Court, sitting as a Court of<br />

Arbitration, may conduct the arbitration in such manner as it considers appropriate. 18<br />

Unless the parties have agreed upon the place where the arbitration is to be held,<br />

such place will be determined by the Court, having regard to the circumstances of the<br />

case.<br />

Besides making determinations on matters brought before it and sitting as a court of<br />

arbitration, the Court can give an advisory opinion on questions of law arising from<br />

the provisions of the Treaty affecting <strong>COMESA</strong>, at the request of the Authority, the<br />

Council or a Member State. 19 In the exercise of its advisory function, the Court will be<br />

governed by the provisions of the Treaty and the Rules of Court relating to the<br />

resolution of disputes to the extent that the Court considers appropriate.<br />

3 Agents, lawyers, experts and costs<br />

Member States, institutions or other eligible parties are to be represented before the<br />

Court by an agent who is a lawyer entitled to practise before a court of a Member<br />

State. This requirement is mandatory. The agent may, however, be assisted by an<br />

adviser or by a lawyer certified to practise before a court of a Member State. Agents<br />

appearing before the Court enjoy immunity in respect of words spoken or written by<br />

them concerning the case, or the parties. In particular, their papers and documents<br />

relating to the proceedings are exempt from both search and seizure.<br />

WTO dispute settlement system takes (6 months if case is not appealed and 9 months if the case is<br />

appealed).<br />

18 Rule 6 of the Rules of Arbitration.<br />

19 It is not clear from a reading of the Treaty what the status of these advisory opinions is.<br />

10

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

In order to qualify for the privileges and immunities, the agents need to produce proof<br />

of their status. These privileges and immunities are granted exclusively in the<br />

interests of the proper conduct of proceedings. The Court may waive the privileges<br />

and immunities where it considers that the proper conduct of proceedings will not be<br />

hindered by so doing. In addition, any agent whose conduct towards the Court, a<br />

Judge or the Registrar is incompatible with the dignity of the Court, or who uses his<br />

rights for purposes other than those for which they are granted, may at any time be<br />

excluded from the proceedings.<br />

The Court can appoint one or more experts to report to it on specific issues it wishes<br />

to determine. The parties to the dispute are expected to give to the expert any<br />

relevant information or any relevant documents or goods that the expert may require.<br />

When the Court is sitting as a court of arbitration, it may also order that an expert's<br />

report be obtained.<br />

An important aspect of any dispute settlement system is the aspect of costs. The<br />

amount of costs to be paid may be the determining factor as to whether or not one<br />

will participate in proceedings before the Court. Parties in a dispute can run up a<br />

huge bill of costs and the other party usually demands that the other pay all the costs<br />

associated with the case. The rules and regulations of the Court provide an intricate<br />

system of how the costs of the participation of the parties in the dispute shall be paid<br />

at the end of the case. It is important to note that proceedings before the Court are<br />

free of charge, meaning that nothing has to be paid to the Court or to the judges by<br />

the participating parties. However, where a party has caused the Court to incur costs<br />

that could have been avoided, the Court may order that party to refund those costs.<br />

And where copying or translation work is carried out at the request of a party, the<br />

costs will be paid for by that party if the Registrar considers those costs excessive.<br />

The costs that have to be paid and that are ‘recoverable’, relate only to sums payable<br />

to witnesses and experts, and expenses necessarily incurred by the parties for the<br />

purpose of the proceedings, in particular the travel and subsistence expenses and<br />

the remuneration of agents, advisers or lawyers. In terms of the regulations of the<br />

Court, the decision as to costs shall be given in the final judgment or in the order<br />

which closes the proceedings. The principle as regards matters brought before the<br />

11

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

Court is that the unsuccessful party shall be ordered to pay the costs if they have<br />

been applied for by the successful party. If costs are not claimed, the parties will bear<br />

their own costs. Where there are several unsuccessful parties, the Court will decide<br />

how the costs are to be shared among them. Where each party succeeds on some<br />

and fails on other issues in the case, or where the circumstances are exceptional, the<br />

Court may order that the costs be shared or that the parties bear their own costs. The<br />

Court may order a party, even if successful, to pay costs, which the Court considers<br />

that party to have unreasonably caused the opposite party to incur.<br />

A party who discontinues or withdraws from proceedings shall be ordered to pay the<br />

costs of the proceedings up to the point of discontinuation, if they have been applied<br />

for in the other party's pleadings. However, if the party who discontinues or withdraws<br />

from proceedings makes a request to the Court, the costs could be borne by the<br />

other party who has not withdrawn, if this appears justified by the conduct of that<br />

party. Where a case does not proceed to judgment, the costs will be paid at the<br />

discretion of the Court. Parties may choose to agree as to how the costs will be<br />

borne by either one of them. Where this happens, the decision as to costs will be in<br />

accordance with the parties’ agreement. In proceedings between <strong>COMESA</strong> and its<br />

employees, <strong>COMESA</strong> shall bear its own costs.<br />

When the Court is sitting as a court of arbitration, it will fix the costs of arbitration in<br />

its award. In such a case, the term 'costs' shall be <strong>under</strong>stood to include the fees of<br />

the Court to be fixed by the Court itself, the travel and other expenses incurred by the<br />

Court, the costs of expert advice and of other assistance required by the Court, the<br />

travel and other expenses of witnesses, to the extent that such expenses are<br />

approved by the Court, and the costs for legal representation and assistance of the<br />

successful party, if such costs were claimed during the arbitral proceedings, and only<br />

to the extent that the Court determines that the amount of such costs is reasonable.<br />

Where an expert is engaged, the Court may request the parties, or one of them, to<br />

lodge security for the costs of the expert's report. It is expected that the fees of the<br />

Court will be reasonable in amount, taking into account the amount in dispute, the<br />

complexity of the subject matter, the time spent by the Court, and any other relevant<br />

circumstances of the case.<br />

12

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

The costs of arbitration will, in principle, be borne by the unsuccessful party. The<br />

Court may, however, apportion such costs between the parties if it determines that<br />

apportionment is reasonable. With respect to the costs of legal representation and<br />

assistance, the Court may determine which party will bear such costs, or may<br />

apportion such costs between the parties if it determines that apportionment is<br />

reasonable. On its establishment as a court of arbitration, the Court may request<br />

each party to deposit an equal amount as an advance for the costs, and may request<br />

supplementary deposits from the parties during the course of the arbitral<br />

proceedings. If the required deposits are not paid in full within thirty days after the<br />

receipt of the request, the Court will inform the parties in order that one or another of<br />

them may make the required payment. If such payment is not made, the Court may<br />

order the suspension or termination of the arbitral proceedings.<br />

The bills of costs so far filed have ranged from a high of US$ 463.084, which was<br />

taxed and allowed at US$145,448, to a low of US$12,277.90, which was taxed and<br />

allowed at US$7,536.00. 20 Extracts of court documents may be obtained on payment<br />

of US$2.00 per page. 21<br />

4 Some decided cases<br />

At the end of 2003 22 the Court had adjudicated upon 19 cases 23 , either as the Court<br />

proper or as a court of arbitration. These disputes were brought before the Court by<br />

Member States, <strong>COMESA</strong>, and by both natural and legal persons. The cases have<br />

dealt with a wide range of issues, including questions of the exhaustion of local<br />

remedies, the Court’s jurisdiction, locus standi and costs.<br />

20 It was not possible to determine how these costs compare with costs in cases decided by the WTO or<br />

the ICJ.<br />

21 According to Habben Nkonkesha, Officer in Charge of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court of Justice, in an e-mail<br />

sent to the writer on 26 July 2005.<br />

22 The Judges’ contracts expired in June 2003, and the vacuum that followed was only filled in June<br />

2005 by the appointment of new Judges.<br />

23 See attached list of cases filed, disposed off and pending, 2005.<br />

13

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

In the matter of The Republic of Kenya and Commissioner of Lands v Coastal<br />

Aquaculture 24 , Coastal Aquaculture, a limited liability company incorporated <strong>under</strong><br />

the Laws of the Republic of Kenya, filed with the Court an application asking the<br />

Court to stop the Republic of Kenya, its servants, agents or officers from acquiring<br />

certain of its land, without (among other things) first making provision for the advance<br />

payment of adequate compensation and payment of damages, complying with the<br />

relevant provisions of the Constitution of Kenya, and complying fully with the<br />

provisions of the land acquisition of Kenya. By legal notices issued in November<br />

1993, the Commissioner of Lands of Kenya had shown an intention to compulsorily<br />

acquire the land belonging to Coastal Aquaculture, in terms of the power for<br />

compulsory acquisition of land in Kenya conferred on him by the Constitution.<br />

Coastal Aquaculture had brought this matter before the courts in Kenya in 1994, and<br />

the courts had held that the notices of acquisition issued by the Government of<br />

Kenya were defective and invalid. This judgment had received the full approval of the<br />

Court of Appeal. However, on 16 June 2000, the Commissioner of Lands published<br />

further notices indicating the Government’s intention once again to acquire Coastal<br />

Aquaculture’s same land. The notices were drawn in identical terms to the previous<br />

Gazette Notices of 1993 which had been declared defective, null and void.<br />

The Court began by observing that as an organ of the Treaty it had no power outside<br />

what is bestowed upon it by the Treaty, and noted that Article 19 of the Treaty<br />

enjoined the Court to 'ensure the adherence to law in the interpretation and<br />

application of this Treaty'. Unless a party is imbued with a legal right to refer matters<br />

to the Court for adjudication in terms of the Treaty, he has no locus standi to file a<br />

Reference in the Court, the Court further observed. It noted however, that Coastal<br />

Aquaculture, being a legal person resident in a Member State, had the requisite locus<br />

standi to refer proceedings to the Court for determination only if it had exhausted all<br />

local remedies in the national courts or tribunals of Kenya.<br />

24 Reference No. 3 of 2001. [JUDGMENT OF 26/4/2002]. The full citation of the Cases decided by the Court begins<br />

by stating the parties involved, followed by a reference number, the subject matter, what the Court’s decision was<br />

and then the judgment number. The full citation of the case referred to here would be as follows: 'The Republic of<br />

Kenya and Commissioner of Lands v Coastal Aquaculture – Reference No. 3 of 2001. Interlocutory Application to<br />

strike out Reference for want of Locus Standi. The Application was allowed. [JUDGMENT OF 26/4/2002] '.<br />

14

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

Indeed, Coastal Aquaculture had filed a civil suit in 1996 in the High Court of Kenya<br />

at Nairobi, seeking damages purportedly suffered as a result of the prohibited<br />

attempts by the Government to compulsorily acquire its land. It did not, however,<br />

prosecute that action to finality in the High Court of Kenya, having withdrawn it just<br />

before commencing the proceedings in the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court of Justice. It gave the<br />

reason for the withdrawal as the ‘unbearable’ situation it found itself in – for which the<br />

national courts were powerless to provide relief, since the Government, over a period<br />

of eight years or more, had been unable to follow the simple legal procedures laid<br />

down in the Land Acquisition Act to their logical conclusion, despite repeated<br />

guidance from the High Court and the Court of Appeal of Kenya.<br />

The Court stated that the withdrawal by Coastal Aquaculture of its action for<br />

damages in a civil suit did not constitute exhaustion by it of the legal remedies in the<br />

national courts of Kenya. As such, Coastal Aquaculture did not have the locus standi<br />

to commence a case before the Court. Since <strong>under</strong> the Kenyan law once the<br />

responsible Minister certifies that the land is acquired, that acquisition can only be<br />

withdrawn as a matter of Ministerial discretion, and since a court of law cannot direct<br />

the Minister to withdraw the acquisition, the Court ruled that the matter of the<br />

compulsory acquisition of Coastal Aquaculture’s land was still pending in Kenya and<br />

that, therefore, Coastal Aquaculture could not commence a case before the Court.<br />

The application by the Government of Kenya to strike out Coastal Aquaculture’s case<br />

for want of locus standi was allowed, and in the circumstances of the case, the Court<br />

made no order as to costs.<br />

As has already been stated, reference of a matter to the Court by legal and natural<br />

persons is permitted <strong>under</strong> Article 26 of the Treaty in respect of the legality of any<br />

act, regulation, directive, or decision of a Member State on the grounds that such act,<br />

directive, decision or regulation is unlawful or is an infringement of the provisions of<br />

the Treaty. It would have been useful for the Court to explain whether the action by<br />

the Government of Kenya was unlawful as judged against the laws of Kenya, or<br />

whether it was an infringement of the provisions of the Treaty. Presumably the Court<br />

would have addressed this issue if it had found that Coastal Aquaculture had<br />

exhausted the legal remedies in the national courts of Kenya.<br />

15

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

In the case of Ethiopia v Eritrea 25 the Government of Ethiopia sought from the<br />

Government of Eritrea, among other things, the release of goods belonging to<br />

Ethiopians detained at the Eritrean Ports of Assab and Massawa. The Government of<br />

Eritrea objected to the case through a preliminary application on the grounds that this<br />

was an abuse of the process of the Court, and was not a matter that arose from the<br />

Treaty, which would entitle the Court to hear the action. By letter, the Government of<br />

Eritrea sought an adjournment of its preliminary application. On its part, the<br />

Government of Ethiopia also sought a stay of proceedings citing the fact that prior to<br />

the service of the notice of hearing of the preliminary application, the Governments of<br />

Ethiopia and Eritrea had entered into a Peace Agreement <strong>under</strong> which the dispute<br />

could be settled. The Government of Eritrea did not oppose the application for the<br />

stay of proceedings.<br />

In the circumstances, the Court held that the matter be adjourned sine die, that is,<br />

indefinitely, thereby leaving the parties to recommence the action as and when they<br />

thought fit. 26 The costs, the Court said 'will be in the cause', meaning that a<br />

determination as to costs would only be made when the matter was finalized.<br />

In the case of Martin Ogang v Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development<br />

Bank (PTA Bank) and Dr Michael Gondwe 27 Martin Ogang, who was at one time the<br />

President of the Eastern and Southern Africa Trade and Development Bank, sought<br />

an order for the committal to jail for six months of Michael Gondwe, the then acting<br />

President of the PTA Bank, and two other persons in the employment of the Bank,<br />

and for the sequestration of all their properties for being in contempt of the Court in<br />

that they had disobeyed orders earlier given by the Court. Mr Ogang had earlier filed<br />

an application seeking orders to suspend and to stop a scheduled meeting of the<br />

PTA Bank Board of Directors and Board of Governors, and to stop the Board of<br />

Directors from committing certain other acts. On the same day that the application<br />

was filed, and without it having been served on the Bank and its acting President, the<br />

President of the Court had granted the orders sought.<br />

25 Judgment of 21/3/2001. This remains the only case so far brought by one state against another .<br />

26 Since a case can be postponed indefinitely, there is no provision in the Rules of Court providing for<br />

the lapse of a case if parties do not pursue it within a certain period.<br />

27 Judgment of 27/3/2001.<br />

16

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

The Rules of Court 28 provide that an application such as that which had been filed by<br />

Mr Ogang be served on the opposite party, and that the President prescribe a short<br />

period within which either party may submit written or oral observations. Even though<br />

the rules then go on to provide that the President may grant the application even<br />

before the observations of the opposite party have been submitted, the Court<br />

observed in this case that this does not exempt the initial mandatory requirement<br />

(that the application must first be served on the opposite party), from being complied<br />

with before an application can be granted. The Court reasoned that the only matter<br />

that could be dispensed with before an application had been granted, was the<br />

submission of the observations of the opposite party; and it observed that if the<br />

intention of the rules was that such a drastic remedy as a suspension order could be<br />

made by the President without the opposite party having been first served with the<br />

application involved, this would have been clearly spelled out.<br />

The Court then ruled that it was obvious that the order of the President made in<br />

favour of Mr Ogang, and the disobedience thereof, which constituted the foundation<br />

of the case, was contrary to the applicable rules, and was, therefore, a nullity. As<br />

such, it could not possibly be the basis of the committal for contempt of court and the<br />

sequestration of property, or other proceeding, against the Bank, Mr Gondwe and the<br />

other two bank employees. On that ground, the application was dismissed. Since at<br />

the beginning of the court action the Agents appearing for the Bank and Mr Gondwe<br />

had refused to take part in the proceedings and 'stalked out of court', the Court made<br />

no order as to costs.<br />

In the case of Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank (PTA<br />

Bank) and Dr Michael Gondwe v Martin Ogang 29 the PTA Bank and Dr Michael<br />

Gondwe challenged the jurisdiction of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court to hear an application for a<br />

suspension order filed by Mr Ogang. By that application, Mr Ogang asked the Court<br />

for an order suspending the operation of a resolution passed by the Board of<br />

Directors of the PTA Bank. The PTA Bank argued that, by its Charter, it enjoyed<br />

certain privileges and immunities from legal proceedings in territories of PTA Member<br />

28 Sub-rule 1 of Rule 76.<br />

29 Judgment 29/372001.<br />

17

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

States. It contended further that the failure by Mr Ogang to state the law or statute,<br />

upon which his standing before the Court was established, deprived him of locus<br />

standi, and disentitled him from any of the remedies he sought, and that the Court<br />

lacked jurisdiction to entertain the case, or to try the issues raised, as Mr Ogang had<br />

not pleaded the law or statute upon which the Court’s jurisdiction was founded.<br />

Regarding the PTA Bank’s argument that it was granted privileges and immunities<br />

from prosecution by its Charter, the Court observed that the original Charter of the<br />

PTA Bank had stipulated that cases could be brought against the Bank in the<br />

territories of the Member States, or elsewhere, in a court of competent jurisdiction.<br />

But by an amendment subsequently made by its Board of Governors, the PTA Bank<br />

was granted immunity from every form of legal process. The Court noted that the<br />

Treaty did not provide 'for the existence of a rogue organ or institution flouting with<br />

impunity, all the rules of the organization from which it derives birth', and that any<br />

privileges and immunities that the PTA Bank assumed by an amendment of its<br />

Charter were ultra vires (went beyond) the Treaty that breathed life into the Bank.<br />

The Court then recalled the well-known principle of law that an international<br />

organization cannot confer on itself privileges and immunities to be granted to it by its<br />

member states. The Court said that the amended Article of the Charter of the PTA<br />

Bank purporting to confer privileges and immunities upon itself, conferred no<br />

privileges and immunities that had the force of law within <strong>COMESA</strong>. As to the locus<br />

standi of Mr Ogang, the Court said that there were no Rules of the Court that had<br />

been breached, so Mr Ogang had locus standi in the matter.<br />

This application was supposed to have been heard on 22 March 2001. The Notice<br />

stipulating the date and time of hearing of the application had been served on the<br />

legal representatives of the parties as early as 23 January 2001. However, on the<br />

day of the hearing, counsel for the PTA Bank applied for a deferment of the<br />

application on the ground that leading counsel was not available. The Court observed<br />

that it had a very tight schedule arising from the fact that it is composed of Judges<br />

from different countries, and considered the omission of leading counsel to appear on<br />

the scheduled date to argue the application, a slight on the Court. 'It is for counsel to<br />

wait on the Court and not the Court to wait on counsel', the Court stressed, and<br />

added that such a situation was unacceptable and one for which the party asking for<br />

18

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

deferment had to be ‘mulcted in costs’. Consequently, the PTA Bank was ordered to<br />

bear the wasted costs of the abortive hearing on 22 March 2001. Since the Court<br />

was satisfied that the application on both issues was misconceived and without merit,<br />

it dismissed the application ‘with costs’, meaning that the PTA Bank, besides having<br />

to meet its own costs, had to meet Mr Ogang’s costs as well.<br />

In the case of Building Design Enterprise v Common Market for Eastern and<br />

Southern Africa 30 the Court sat as a court of arbitration. However, the parties to the<br />

arbitration by means of a letter addressed to the Registrar of the Court intimated that<br />

they had reached a settlement of their dispute. That being so, the Court ordered that<br />

the arbitration be removed from the Register of the Court. As regards costs, the<br />

parties indicated in the same letter that they had reached a mutual agreement<br />

regarding costs. In the circumstances, the Court ordered that costs would be in terms<br />

of that mutual agreement.<br />

5 Some concluding thoughts<br />

It would appear from the cases decided that the Court has so far functioned as it<br />

should, and has been able to provide an effective system of judicial safeguards<br />

where the law has been challenged or applied. The Judges have ensured that the<br />

law is not interpreted and applied differently in each Member State, and that as a<br />

shared legal system, the system remains identical, allowing for legal or natural<br />

persons affected by any act, directive, decision or regulation of the Council or<br />

Member State, or the unlawful infringement of the provisions of the Treaty, to request<br />

the Court to determine the legality of such an act, directive, decision or regulation.<br />

However, a delay in the hearing of cases was experienced when the Judges’<br />

contracts expired in June 2003. The vacuum created by the absence of Judges from<br />

June 2003 to May 2005, was only filled by the appointment of new Judges in June<br />

2005.<br />

So far, parties that have brought cases before the Court appear to have had no<br />

problems as to information gathering and presentation or as regards any aspect of<br />

30 Application for Arbitration No. 1 of 2002.<br />

19

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

bringing or defending a case before the Court. 31 It could be rather limiting, in terms of<br />

costs, however, that every party to a matter before the Court is to be represented by<br />

counsel.<br />

The Court’s jurisdiction is wide enough, able as it is to adjudicate upon disputes to<br />

which Member States, the Secretary General, residents of Member States (which<br />

includes individuals and legal persons) may be parties. It is quite progressive that a<br />

Member State that considers that another Member State, or the Council, has failed to<br />

fulfil an obligation <strong>under</strong> the Treaty, or has infringed a provision of the Treaty, can<br />

refer a case to the Court for determination, or for arbitration.<br />

One aspect that could disadvantage the development of the Court’s jurisprudence is<br />

the fact that no dissenting opinion of a Judge is allowed when the Court delivers a<br />

judgment. The Court can deliver only one judgment, and the conclusions reached by<br />

the majority of the Judges after final deliberations shall be the decision of the Court.<br />

Although Judges deliberating in closed session must state their opinion in a case and<br />

give the reasons for such opinion, they cannot in open Court disagree with the<br />

judgment, or aspects of it. It is doubtful that judges always agree on every aspect of a<br />

judgment, and preventing a judge from making his/her dissenting view publicly<br />

known, and the reasons for that dissent, robs the jurisprudence of some flavour in its<br />

development. History has shown that dissenting judges’ opinions are a rich<br />

contribution to the development of jurisprudence and the progressive development of<br />

any body of law. Sometimes what one judge may say in dissent may gain currency,<br />

and with time and changing circumstances, become accepted principle.<br />

While the Treaty states that the Court shall have jurisdiction to adjudicate upon all<br />

matters which may be referred to it pursuant to the Treaty, and that decisions of the<br />

Court on the interpretation of the provisions of the Treaty have precedence over<br />

decisions of national courts, the Treaty does not address the question of what<br />

happens in the case of trade disputes, where it is possible for parties to bring<br />

disputes both <strong>under</strong> the <strong>COMESA</strong> dispute settlement system and the World Trade<br />

31 According to Habben Nkonkesha, Officer in Charge of the <strong>COMESA</strong> Court of Justice, in sentiments<br />

expressed in an e-mail sent to the writer on 22 July 2005.<br />

20

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system. This is possibly one issue on which<br />

an advisory opinion from the Court could be sought.<br />

The Members’ conviction on setting up the Court was that the stronger the Court of<br />

Justice, the stronger the foundation upon which <strong>COMESA</strong> will develop. The Court<br />

has been better able to contribute to the process of regional integration as one<br />

integrated judicial body, rather than the pre-existing three relatively weak and limited<br />

judicial bodies. However, a need appears for the Court to conduct publicity seminars<br />

in Member States, which should prove most beneficial to all stake-holders who would<br />

then gain an insight into the operations of the Court, as little appears to be known<br />

about it. It can be imagined that while the task entrusted to agents and lawyers<br />

appointed to handle the process/documents of the Court may appear routine since<br />

the agents and lawyers are supposed to be competent to handle Court processes in<br />

their national courts, these lawyers are, by the nature of their jobs, of varied origin<br />

and practical experience.<br />

References<br />

1. Building Design Enterprise v Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa,<br />

Application for Arbitration No. 1 of 2002.<br />

2. <strong>COMESA</strong> website http://www.comesa.int/index_html/view<br />

3. Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank (PTA Bank) and Dr<br />

Michael Gondwe v Martin Ogang, Judgment 29/3/2001.<br />

4. Martin Ogang v Eastern and Southern African Trade and Development Bank<br />

(PTA Bank) and Dr Michael Gondwe, Judgment 27/3/2001.<br />

5. The Republic of Kenya and Commissioner of Lands v Coastal Aquaculture,<br />

Reference No. 3 of 2001.<br />

6. Treaty Establishing the Common Market of East and Southern Africa of 1994.<br />

21

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

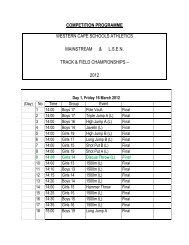

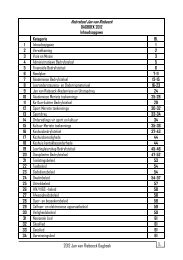

List of Cases Filed, Disposed of, and Pending<br />

DATE<br />

CAUSE<br />

PARTIES<br />

PEND-<br />

WITHDRAWN<br />

SETTLED OUT<br />

DATE OF<br />

STATUS<br />

FILED<br />

NO.<br />

ING<br />

OF COURT<br />

JUDGE-<br />

MENT<br />

24/9/1999 1/99 ETHIOPIA<br />

vERITREA<br />

- - - 21/3/2001<br />

Adjourned sine<br />

die with leave to<br />

apply<br />

20/1/2000 1A/2000 MARTIN<br />

OGANG vPTA<br />

BANK<br />

- - - 30/03/2001<br />

Dismissed<br />

Withdrawn<br />

20/1/2000 1B/2000 MARTIN<br />

- Notice of<br />

- -<br />

OGANG vPTA<br />

discontinuous<br />

BANK<br />

Filed on<br />

19/8/2002<br />

31/1/2000 1C/2000 MARTIN<br />

OGANG vPTA<br />

BANK<br />

- - - 30/3/2001<br />

Dismissed<br />

20/1/2000 1D/2000 MARTIN<br />

OGANG v<br />

PTA BANK<br />

- - - 29/3/2001<br />

Dismissed<br />

21/3/2000 1E/2000 MARTIN<br />

OGANG vPTA<br />

BANK<br />

- - - 27/3/2001<br />

Dismissed<br />

20/4/2000 1F/2000 MARTIN<br />

OGANG vPTA<br />

BANK<br />

- - - 27/3/2001<br />

Dismissed<br />

22

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

05/3/2001 1/2001 ETHIOPIA v<br />

ERITREA<br />

- - - 21/3/2001<br />

Application for<br />

stay of<br />

proceedings in<br />

Ref. 1/99<br />

granted with<br />

leave to apply<br />

26/6/2001 2/2001 DR KABETA<br />

MULEYA v<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong><br />

- - - 23/4/2002<br />

Applicant<br />

succeeded on<br />

the principal<br />

prayer<br />

19/7/2001 3 of 001 COASTAL<br />

AQUACULTU<br />

RE<br />

- - - 23/4/2002<br />

Application<br />

struck out for<br />

want of locus<br />

standi<br />

v<br />

THE<br />

REPUBLIC<br />

OF KENYA<br />

27/1/2003 1/2003 KABETA<br />

MULEYA<br />

- - - 01/7/2003<br />

Applicant<br />

awarded<br />

damages for libel<br />

v<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> &<br />

ERASTUS<br />

MWENCHA<br />

05/3/2003 P.A.<br />

1/2003<br />

KABETA<br />

MULEYA<br />

v<br />

- - - 03/4/2003<br />

Second<br />

Respondent<br />

struck out from<br />

the proceedings,<br />

costs awarded to<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> &<br />

Mwencha<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong> &<br />

ERASTUS<br />

MWENCHA<br />

16/4/2002 1 of 2002 BUILDING<br />

DESIGN<br />

- - Parties<br />

reached a<br />

18/10/2002<br />

Settled out of<br />

Court, claim<br />

abandoned<br />

23

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

ENTERPRISE<br />

v<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong><br />

settlement of<br />

their dispute<br />

and the claim<br />

therein had<br />

been<br />

abandoned.<br />

07/8/2002 3 of 2002 BILIKA<br />

SIMAMBA<br />

- - Parties<br />

reached a<br />

25/10/2002<br />

Settled out of<br />

Court, claim<br />

abandoned<br />

v<br />

settlement of<br />

their dispute<br />

<strong>COMESA</strong><br />

and the claim<br />

therein had<br />

been<br />

abandoned.<br />

13/5/2002 2 of 2002 MARTIN<br />

OGANG v<br />

PTA BANK<br />

Pending<br />

for<br />

hearing<br />

- - -<br />

Reference<br />

stayed pending<br />

compliance with<br />

an order for<br />

costs in a<br />

discontinued<br />

reference<br />

25/10/2002 4 of 2002 STANDARD<br />

CHARTERED<br />

FINANCIAL<br />

SERVICES<br />

(LTD) AND 2<br />

OTHERS<br />

v<br />

THE COURT<br />

OF APPEAL<br />

Pending<br />

for<br />

hearing<br />

- - -<br />

On 20/11/2003 it<br />

was ordered that<br />

the Republic of<br />

Kenya be<br />

substituted for<br />

Court of Appeal,<br />

and that King<br />

Wollen Mills Ltd<br />

and Gallot<br />

Industries be<br />

made<br />

Respondents<br />

before Court.<br />

The amended<br />

Reference is<br />

pending for<br />

hearing<br />

OF KENYA<br />

22/1/2004 4 of 2002 MRS.<br />

Pending<br />

- - -<br />

Pending for<br />

hearing<br />

NKURUNZIZA<br />

for<br />

AND 4<br />

hearing<br />

OTHERS<br />

24

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

v<br />

PTA BANK<br />

13/1/2003 4 of 2002 STANDARD<br />

CHARTERD<br />

FINANCIAL<br />

Pending<br />

for<br />

hearing<br />

- - -<br />

Preliminary<br />

application<br />

seeking to struck<br />

out the<br />

substantive<br />

reference<br />

SERVICES<br />

(LTD)<br />

v<br />

Pending<br />

together with a<br />

notice of<br />

objection for lack<br />

of jurisdiction<br />

THE<br />

REPUBLIC<br />

OF KENYA<br />

AND 2<br />

OTHERS<br />

31/7/2003 2 of 2002 PTA BANK<br />

v<br />

MARTIN<br />

OGANG<br />

Pending<br />

for<br />

hearing<br />

- - - Preliminary<br />

application in<br />

Reference No. 2<br />

of 2002 filed<br />

pursuant to the<br />

Judgment and<br />

Ruling of costs<br />

ordered by the<br />

Court which<br />

were not paid.<br />

The Applicant<br />

may apply to<br />

have Reference<br />

No. 2 of 2002<br />

struck off.<br />

25

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

26<br />

Working Papers<br />

2002<br />

US safeguard measures on steel imports: specific implications<br />

by Niel Joubert & Rian Geldenhuys.<br />

WP 1/2002, April<br />

A few reflections on Annex VI to the SADC Trade Protocol<br />

by Jan Bohanes<br />

WP 2/2002, August<br />

Competition policy in a regional context: a SADC perspective on trade investment & competition issues<br />

by Trudi Hartzenberg<br />

WP 3/2002, November<br />

Rules of Origin and Agriculture: some observations<br />

by Hilton Zunckel<br />

WP 4/2002, November<br />

2003<br />

A new anti-dumping regime for South Africa and SACU<br />

by Stuart Clark & Gerhard Erasmus<br />

WP 1/2003, May<br />

Why build capacity in international trade law?<br />

by Gerhard Erasmus<br />

WP 2/2003, May<br />

The regional integration facilitation forum: a simple answer to a complicated issue?<br />

by Henry Mutai<br />

WP 3/2003, July<br />

The WTO GMO dispute<br />

by Maxine Kennett<br />

WP 4/2003, July<br />

WTO accession<br />

by Maxine Kennett<br />

WP 5/2003, July<br />

On the road to Cancun: a development perspective on EU trade policies<br />

by Faizel Ismail<br />

WP 6/2003, August<br />

GATS: an update on the negotiations and developments of trade in services in SADC<br />

by Adeline Tibakweitira<br />

WP 7/2003, August<br />

An evaluation of the capitals control debate: is there a case for controlling capital flows in the SACU-US free<br />

trade agreement?<br />

by Calvin Manduna<br />

WP 8/2003, August<br />

Non-smokers hooked on tobacco<br />

by Calvin Manduna<br />

WP 9/2003, August<br />

Assessing the impact of trade liberalisation: the importance of policy complementarities and policy processes<br />

in a SADC context<br />

by Trudi Hartzenberg<br />

WP 10/2003, October<br />

An examination of regional trade agreements: a case study of the EC and the East African community<br />

by Jeremy Everard John Streatfeild<br />

WP 11/2003, October<br />

Reforming the EU sugar regime: will Southern Africa still feature?<br />

by Daniel Malzbender<br />

WP 12/2003, October<br />

2004<br />

Complexities and inadequacies relating to certain provision of the General Agreement on Trade in Services<br />

by Leon Steenkamp<br />

WP 1/2004, March<br />

Challenges posed by electronic commerce to the operation and implementation of the General Agreement on<br />

Trade in Services<br />

by Leon Steenkamp<br />

WP 2/2004, March<br />

Trade liberalisation and regional integration in SADC: policy synergies assessed in an industrial organisation<br />

framework<br />

by Martine Visser and Trudi Hartzenberg<br />

WP 3/2004, March<br />

Tanzania and AGOA: opportunities missed?<br />

by Eckart Naumann and Linda Mtango<br />

WP 4/2004, March

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

Rationale behind agricultural reform negotiations<br />

by Hilton Zunkel<br />

WP 5/2004, July<br />

The impact of US-SACU FTA negotiations on Public Health in Southern Africa<br />

by Tenu Avafia<br />

WP 6/2004, November<br />

Export Performance of the South African Automotive Industry<br />

by Mareika Meyn<br />

WP 7/2004 December<br />

2005<br />

Textiles and clothing: Reflections on the sector’s integration into the post-quota environment<br />

by Eckart Naumann<br />

WP 1/2005, March<br />

Assessing the Causes of Sub-Saharan Africa's Declining Exports and Addressing Supply-Side Constraints<br />

by Calvin Manduna<br />

WP 2/2005, May<br />

A Few Reflections on Annex VI to the SADC Trade Protocol<br />

by Jan Bohanes<br />

WP 3/2005, June<br />

Tariff Liberalisation Impacts of the EAC Customs Union in Perspective<br />

by Heinz - Michael Stahl<br />

WP 4/2005, August<br />

Trade facilitation and the WTO: A critical analysis of proposals on trade facilitation and their implications for<br />

African countries.<br />

by Gainmore Zanamwe<br />

WP 5/2005, August<br />

An evaluation of the alternatives and possibilities for countries in sub-Saharan Africa to meet the sanitary<br />

standards for entry into the international trade in animals and animal products<br />

by Gideon K. Brückner<br />

WP 6/2005, October<br />

Trade Briefs<br />

2002<br />

Cost sharing in international dispute settlement: some reflections in the context of SADC<br />

by Jan Bohanes & Gerhard Erasmus.<br />

TB 1/2002, July<br />

Trade dispute between Zambia & Zimbabwe<br />

by Tapiwa C. Gandidze.<br />

TB 2/2002, August<br />

2003<br />

Non-tariff barriers: the reward of curtailed freedom<br />

by Hilton Zunckel<br />

TB 1/2003, February<br />

The effects of globalization on negotiating tactics<br />

by Gerhard Erasmus & Lee Padayachee<br />

TB 2/2003, May<br />

The US-SACU FTA : implications for wheat trade<br />

by Hilton Zunckel<br />

TB 3/2003, June<br />

Memberships in multiple regional trading arrangements : legal implications for the conduct of trade<br />

negotiations<br />

by Henry Mutai<br />

TB 4/2003, August<br />

2004<br />

Apparel Trade and Quotas: Developments since AGOA’s inception and challenges ahead<br />

by Eckart Naumann<br />

TB 1/2004, March<br />

Adequately boxing Africa in the debate on domestic support and export subsidies<br />

by Hilton E Zunckel<br />

TB 2/2004, July<br />

Recent changes to the AGOA legislation<br />

by Eckart Naumann<br />

TB 3/2004, August<br />

2005<br />

Trade after Preferences: a New Adjustment Partnership?<br />

by Ron Sandrey<br />

TB1/2005, June<br />

27

tralac Working Paper no. 7<br />

www.tralac.org<br />

TRIPs and Public Health: The Unresolved Debate<br />

by Tenu Avafia<br />

TB2/2005, June<br />

Daring to <strong>Dispute</strong>: Are there shifting trends in African participation in WTO dispute settlement?<br />

by Calvin Manduna<br />

TB3/2005, June<br />

South Africa’s Countervailing Regulations<br />

by Gustav Brink<br />

TB4/2005, August<br />

Trade and competitiveness in African fish exports: Impacts of WTO and EU negotiations and regulation<br />

by Stefano Ponte, Jesper Raakjær Nielsen, & Liam Campling<br />

TB5/2005, September<br />

28