Abu-Lughod Asia.pdf

Abu-Lughod Asia.pdf

Abu-Lughod Asia.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

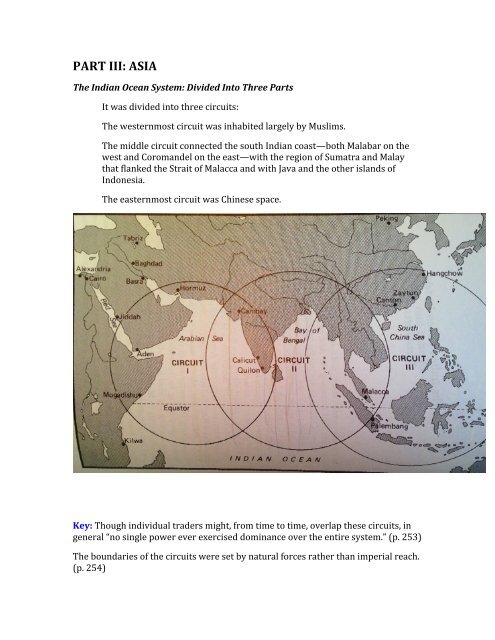

PART III: ASIA <br />

The Indian Ocean System: Divided Into Three Parts <br />

It was divided into three circuits: <br />

The westernmost circuit was inhabited largely by Muslims. <br />

The middle circuit connected the south Indian coast—both Malabar on the <br />

west and Coromandel on the east—with the region of Sumatra and Malay <br />

that flanked the Strait of Malacca and with Java and the other islands of <br />

Indonesia. <br />

The easternmost circuit was Chinese space. <br />

Key: Though individual traders might, from time to time, overlap these circuits, in <br />

general “no single power ever exercised dominance over the entire system.” (p. 253) <br />

The boundaries of the circuits were set by natural forces rather than imperial reach. <br />

(p. 254)

See pp. 256-‐57 for tables on winds/sailing conditions and times of year. <br />

When the Chinese (Ming Dynasty) withdrew from the sea in 1435, it created a <br />

power vacuum that would be filled by the Portuguese. <br />

Chapter 8: The Indian Subcontinent: On the Way to Everywhere. <br />

India has two macroecological zones: the Malabar Coast and the Coromandel. <br />

Sea trade to and from Gujarat, and possibly the Malabar Coast was already <br />

happening in 2000 BCE. <br />

The Abbasids were revitalizing this route in the 8 th century CE.

In the Mediterranean a perpetual state of naval warfare existed from the ninth <br />

century onward, and commercial ships, therefore, always traveled in military <br />

convoys. That was not true in the Indian Ocean since sea warfare did not <br />

characterize commerce there. The trade was essentially peaceful. (p. 275) <br />

It was a system of laissez-‐faire and multiethnic shipping, established over long <br />

centuries of relative peace and tolerance. In December 1500 the Portuguese captain, <br />

Cabral decided to attack and seize two Muslim ships loading pepper at Calicut. He <br />

was “sinning” against an “unwritten law.” (p. 276)

This use of violence, force, and extortion characterized the Portuguese approach in <br />

the early 16 th century. <br />

Lessons from the Indian Case <br />

India seems to have been indifferent to much of the items traded. <br />

Indian wealth kept her from being more aggressive in being involved in the <br />

sea trade. <br />

This meant that she was vulnerable to the expansion of sea power on either <br />

side of her.

Chapter 9: The Straight and Narrow <br />

The entrepot’s on the straight were important, but geography was somewhat <br />

arbitrary. Any port along the straight could have become an important <br />

intermediary. <br />

Sometimes, as in the case of Srivijaya, representatives could become important <br />

because they gained access to Chinese ports.

Lessons from the Straits: <br />

Comprador states that serve as gateways or interchange points for others are <br />

fully dependent upon the industrial production and commercial interests of <br />

the regions that use them. <br />

The existence of locally produced assets (even aromatics, spices, and <br />

precious metals) by no means guarantees a market; it only makes one <br />

possible. <br />

Whenever the Chinese moved aggressively outward, the intermediary ports <br />

paradoxically became more prosperous but less important. Whenever the <br />

Chinese pulled back from the western circuit or, even worse, interdicted <br />

direct passage of foreign ships into their harbors, the ports in the straits <br />

flourished, but only because Chinese vessels took up the easternmost circuit <br />

slack by meeting their trading partners at Palembang, Kedah, or, later, <br />

Malacca. <br />

When Europe filled that defenseless vacuum in the sixteenth century, the <br />

‘old’ world system of the thirteenth century became the embryo of the <br />

‘modern’ system that still shapes our world today, albeit with declining <br />

power. (p. 313) <br />

Today, Singapore most closely resembles its predecessor, Malacca.

Chapter 9: All the Silks of China <br />

Without question, the most extensive, populous, and technologically <br />

advanced country of the middle ages was China. <br />

<strong>Abu</strong>-‐<strong>Lughod</strong> questions the usual interpretations that see the Chinese as anti-merchant,<br />

especially if that is used as an explanation for their withdrawal <br />

under the Ming Dynasty. <br />

Furthermore, historians have pondered what would have happened if China <br />

had not withdrawn? What if the Portuguese met a Chinese navy instead of <br />

undefended merchant vessels? <br />

Factors related to textile production: <br />

Wool. The demand for grazing land comes into competition with land <br />

for agriculture, thus displacing farmers whose labor is made available <br />

for processing the wool—women largely spinning and men <br />

predominantly fulling, dyeing, and weaving. Wool is easily <br />

transportable in its raw state, which permits a separation between <br />

where it is raised and where it is transformed into cloth. <br />

Cotton and linen follow a different course. Agricultural land remains <br />

under cultivation and crop rotation (with legumes) is required to keep <br />

the soil fertile. This means that there is neither a division of labor <br />

between cotton and flax growers and ordinary farmers nor any <br />

displacement of labor from the land. The raw materials may be <br />

transported for further refining or may receive preliminary <br />

processing and cleaning before being shipped to spinners and <br />

weavers. <br />

The production of silk is very different. It involves a large portion of <br />

rural workers who must be close to the processing area. This leads to <br />

the establishment of agro-‐urban settlements. See pp. 329-‐330 for a <br />

description of the process. This process was not easily transferred to <br />

factories. <br />

Why China Withdrew <br />

It’s often blamed on Confucianism, but why would Confucianism have <br />

been more important under the Ming? <br />

She thinks it is due to the Ming desire to present themselves as the <br />

restorers of Chinese autonomy and values after Mongolian rule. <br />

They also had to divert attention elsewhere as they consolidated their <br />

rule. <br />

The Black Death also contributed to a general economic collapse.

Lessons from the Chinese Case <br />

Geographic position was very important. When the Mongols created <br />

the northern route, China was the place were the circuit could be <br />

complete, as it had sea routes linking to the Indian Ocean.