1 Li8: The Structure of English http://www.ling.cam.ac.uk/Li8 Lecture ...

1 Li8: The Structure of English http://www.ling.cam.ac.uk/Li8 Lecture ...

1 Li8: The Structure of English http://www.ling.cam.ac.uk/Li8 Lecture ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

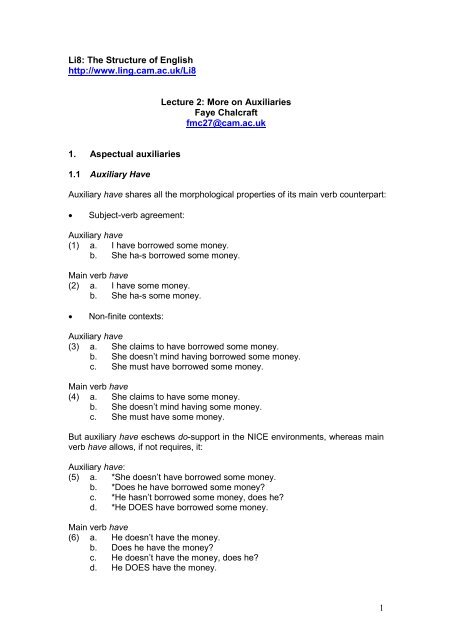

<strong>Li8</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Structure</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>English</strong><br />

<strong>http</strong>://<strong>www</strong>.<strong>ling</strong>.<strong>cam</strong>.<strong>ac</strong>.<strong>uk</strong>/<strong>Li8</strong><br />

<strong>Lecture</strong> 2: More on Auxiliaries<br />

Faye Chalcraft<br />

fmc27@<strong>cam</strong>.<strong>ac</strong>.<strong>uk</strong><br />

1. Aspectual auxiliaries<br />

1.1 Auxiliary Have<br />

Auxiliary have shares all the morphological properties <strong>of</strong> its main verb counterpart:<br />

• Subject-verb agreement:<br />

Auxiliary have<br />

(1) a. I have borrowed some money.<br />

b. She ha-s borrowed some money.<br />

Main verb have<br />

(2) a. I have some money.<br />

b. She ha-s some money.<br />

• Non-finite contexts:<br />

Auxiliary have<br />

(3) a. She claims to have borrowed some money.<br />

b. She doesn’t mind having borrowed some money.<br />

c. She must have borrowed some money.<br />

Main verb have<br />

(4) a. She claims to have some money.<br />

b. She doesn’t mind having some money.<br />

c. She must have some money.<br />

But auxiliary have eschews do-support in the NICE environments, whereas main<br />

verb have allows, if not requires, it:<br />

Auxiliary have:<br />

(5) a. *She doesn’t have borrowed some money.<br />

b. *Does he have borrowed some money?<br />

c. *He hasn’t borrowed some money, does he?<br />

d. *He DOES have borrowed some money.<br />

Main verb have<br />

(6) a. He doesn’t have the money.<br />

b. Does he have the money?<br />

c. He doesn’t have the money, does he?<br />

d. He DOES have the money.<br />

1

Auxiliary have is used to form the perfect:<br />

(7) a. He has swum the Channel.<br />

b. He had swum the Channel.<br />

1.2 Auxiliary Be<br />

Auxiliary be has the same morphology as main verb be:<br />

• Agreement<br />

Auxiliary be<br />

(8) a. I am invited to the party.<br />

b. John i-s invited to the party.<br />

Main verb be<br />

(9) a. I am tired.<br />

b. John i-s tired.<br />

• Non-finite contexts<br />

Auxiliary be<br />

(10) a. John claims to be invited to the party<br />

b. John doesn’t mind being invited to the party.<br />

c. John must be invited to the party.<br />

Main verb be<br />

(11) a. She claims to be tired.<br />

b. She doesn’t mind being tired.<br />

c. She must be tired.<br />

Significantly, main verb be and auxiliary be also pattern alike in the NICE<br />

environments, since not even main verb be allows do-support:<br />

Auxiliary be<br />

(12) a. *John doesn’t be invited to the party.<br />

b. *Does John be invited to the party?<br />

c. *John is invited to the party, doesn’t he?<br />

d. *John DOES be invited to the party.<br />

Main verb be<br />

(13) a. *She doesn’t be tired.<br />

b. *Does she be tired?<br />

c. *She is tired, doesn’t she?<br />

d. *She DOES be tired.<br />

Auxiliary be is used to form the progressive, (14), and the passive, (15):<br />

(14) She is/was singing a song.<br />

(15) <strong>The</strong> song is/was usually sung by Mary.<br />

2

2. Combining auxiliaries<br />

Auxiliaries can be strung together in the following order:<br />

MODAL – PERFECT HAVE – PROGRESSIVE BE – PASSIVE BE – MAIN VERB<br />

Examples with all slots filled are possible:<br />

(16) John may have been being executed.<br />

As are examples with just some slots filled. For instance:<br />

Combining aspect and voice:<br />

(17) a. <strong>The</strong> song is being sung.<br />

b. <strong>The</strong> song has been sung<br />

c. <strong>The</strong> song has been being sung.<br />

Combining modals and aspect:<br />

(18) a. John might have left.<br />

b. John might be leaving.<br />

Combining modals and voice:<br />

(19) a. John might be killed.<br />

b. John might be being killed.<br />

But auxiliaries always select for the inflectional form <strong>of</strong> the next verb in the<br />

sequence (see Huddleston & Pullum 2002: 106):<br />

• Modal + plain form (may leave)<br />

• Perfect have + past participle (has left)<br />

• Progressive be + present participle (is leaving)<br />

• Passive be + past participle (is left)<br />

3. Do-support<br />

3.1 Auxiliary do<br />

Like the other non-modal auxiliaries, auxiliary do has a main verb counterpart:<br />

Auxiliary do<br />

(20) a. I DO juggle.<br />

b. He DO-ES juggle.<br />

Main verb do<br />

(21) a. I do the washing up.<br />

b. He do-es the washing up.<br />

But the differences between them are more significant than what we have seen<br />

with have and be. Indeed, auxiliary do behaves much more like a modal, since,<br />

unlike the aspectual auxiliaries, it l<strong>ac</strong>ks non-finite forms:<br />

3

Auxiliary do<br />

(22) a. *He claims to do juggle.<br />

b. *His doing juggle was impressive (cf. That he did juggle was<br />

impressive).<br />

c. *He will do juggle.<br />

Main verb do<br />

(23) a. He helps to do the washing up.<br />

b. His doing the washing up was a great help.<br />

c. He will do the washing up.<br />

3.2 Do-support as last resort<br />

Standard descriptions <strong>of</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong> auxiliary do have it as a last resort<br />

device that turns up only when there is no alternative:<br />

(24) a. You didn’t do the washing up (cf. *you didn’t the washing up)<br />

b. Did you do the washing up (cf. *did you the washing up?)<br />

But note that there are some contexts in which auxiliary do appears not to be a<br />

last resort:<br />

3.2.1 Spurious do<br />

(25) I, the undersigned, being <strong>of</strong> sound mind do hereby bequeath …<br />

Spurious do is attested in <strong>English</strong> throughout the 16 th C and seems to have<br />

persisted well into 18 th Ellegård (1953: 151), for example, suggests that do + an<br />

infinitive was functionally synonymous with the finite main verb.<br />

<strong>The</strong> use is retained in some south-western British dialects (e.g. Schütze 2004),<br />

though in some such cases do may signal a habitual <strong>ac</strong>t:<br />

(26) a. John visited his brother<br />

b. John did visit his brother.<br />

3.2.2 Propredicate do as an alternative to VP ellipsis in British <strong>English</strong>:<br />

(27) a. John has finished, and Mary has (done) too.<br />

b. I’m leaving early, and you should (do) too.<br />

c. I don’t want to go tomorrow, but I probably will be (doing).<br />

American <strong>English</strong> has something similar (see Kato & Butters 1987):<br />

(28) To refuse to support the rebels in such circumstances, as the<br />

Democrats have done in the case <strong>of</strong> the “contras,” does not<br />

necessarily mean endorsement for the existing regimes.<br />

Is propredicate do auxiliary do or a main verb pro-form?<br />

4

Reasons to think it is a main verb:<br />

• Its morphological forms (participle and plain infinitive) are not those usually<br />

associated with auxiliary do.<br />

• It follows negation and adverbs, appearing in a structural position usually<br />

associated with main verbs:<br />

(29) I hope they will fix the computer, if they haven’t already done.<br />

• It requires do-support in the relevant environments:<br />

(30) He says he likes her, and I think he really does do.<br />

Reasons to think it is an auxiliary:<br />

• It co-occurs with stative antecedents; main verb do is an <strong>ac</strong>tivity verb:<br />

(31) a. Mary has always liked spaghetti. John always has done too.<br />

b. *Mary has always liked spaghetti. John always has done it too.<br />

• It appears in pseudogapping; main verb pro-forms don’t:<br />

(32) a. Have they fed the lions? No, but they have done the tigers.<br />

b. *Have they fed the lions? No, but they have done so the tigers.<br />

So there are at least reasons for wondering whether this might be an auxiliary<br />

use <strong>of</strong> do even though it appears alongside other auxiliaries.<br />

4. Historical development <strong>of</strong> a class <strong>of</strong> modal auxiliaries<br />

Di<strong>ac</strong>hronically, the appearance <strong>of</strong> a separate category <strong>of</strong> modals with a<br />

distinctive set <strong>of</strong> properties is a relatively recent development.<br />

All members <strong>of</strong> the category derive from main verbs, but up until the 16 th century<br />

none <strong>of</strong> the properties mentioned so far char<strong>ac</strong>terised the modals as a class<br />

distinct from main verbs.<br />

For example, modals did have non-finite forms:<br />

(33) but it sufficeth too hem to kunne her Pater Noster, …<br />

but it suffices to them to know their Pater Noster, …<br />

(?c1425 (?c1400) Loll. Serm. 2.325; Denison 1993:310)<br />

You could also get more than one modal in sequence:<br />

(34) Who this booke shall wylle lerne …<br />

He-who this book shall wish learn ..<br />

“He who wishes to master this book.”<br />

(c1483 (?a1480) Caxton, Dialogues 3.37; Denison 1993 : 310)<br />

5

4.1 Lightfoot (1979)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Old <strong>English</strong> (pre-) modals were (pretty normal) main verbs, which between<br />

Old <strong>English</strong> and around 1500 started to undergo a set <strong>of</strong> ‘preposing changes’<br />

which set them apart from the other members <strong>of</strong> their category:<br />

• All the other preterite-present verbs be<strong>cam</strong>e obsolete, leaving those that<br />

remained as a more distinct inflectional class.<br />

• <strong>The</strong>y failed to adopt the new to-infinitive, and took a plain infinitive instead.<br />

• <strong>The</strong>y lost their ability to take (nominal) direct objects<br />

• <strong>The</strong>ir ‘past tense’ forms stopped signal<strong>ling</strong> past time.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se changes made the modals exceptional, and prompted a radical reanalysis<br />

which saw them being treated as a distinct synt<strong>ac</strong>tic class with the properties<br />

associated with the modals today.<br />

Lightfoot’s analysis has proved controversial, with various authors pointing out<br />

that some <strong>of</strong> these developments were in evidence as early as Old <strong>English</strong>, and<br />

questioning the claim that the effects emerged abruptly, or that they would have<br />

been too exceptional to tolerate (see e.g. Warner 1993; Romaine 1981).<br />

4.2 Further reorganisation <strong>of</strong> the auxiliary system (Denison 1998, 2000)<br />

Once the process <strong>of</strong> grammaticalisation by which auxiliaries developed out <strong>of</strong><br />

main verbs had been completed, there has been further reorganisation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

system. Here are some examples.<br />

4.2.1 Loss <strong>of</strong> perfect be<br />

<strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong> be to form the perfect has been in decline since Old <strong>English</strong>:<br />

(35) Now they’re both gone and I can’t repl<strong>ac</strong>e them<br />

(Denison 1998: 135)<br />

4.2.2 <strong>The</strong> emergence <strong>of</strong> new combinatory possibilities<br />

Perfect have + passive be<br />

Old and Middle <strong>English</strong> examples exist, but there remained a tendency to use is<br />

+ past participle where modern <strong>English</strong> would have has been + past participle:<br />

(36) Your Castle is surpriz’d; your Wife, and Babes | Sauagely slaughter’d:<br />

(1623 [1606] Shakespeare, M<strong>ac</strong>beth IV.iii.204, Denison 2000: 13)<br />

Progressive be + passive be<br />

A late-eighteenth-century innovation:<br />

(37) <strong>The</strong> inhabitants <strong>of</strong> Plymouth are under arms, and everything is being done<br />

that can be.<br />

(1779 Mrs. Harris in Lett. 1st Ld. Malmesbury (1870) I.430, Denison 2000: 15)<br />

6

This used to be expressed either using passive be + past participle (omitting<br />

marking <strong>of</strong> progressive) or as passive be + present participle, a construction now<br />

obsolete:<br />

(38) He found that the co<strong>ac</strong>h had sunk greatly on one side, though it was still<br />

dragged forward by the horses;<br />

(1838–9 Dickens, Nickleby v.52, Denison 2000: 15)<br />

(39) <strong>The</strong> house is building.<br />

(Denison 2000: 15)<br />

Other examples<br />

Other combinations with date <strong>of</strong> earliest attestation from Denison (2000):<br />

• modal + perfect have + progressive be + V: ?a1425<br />

• modal + perfect have + passive be + V: c1300<br />

• perfect have + progressive be + passive be + V: 1886/1929<br />

• modal + progressive be + passive be + V: 1915<br />

4.2.3 <strong>The</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> combinations<br />

Gerunds <strong>of</strong> progressive forms have become ungrammatical:<br />

(40) a. Learning Spanish has been very useful.<br />

b. Having learned Spanish has been very useful.<br />

c. Having been learning Spanish has been very useful.<br />

d. *Being learning Spanish has been very useful.<br />

But used to be possible:<br />

(41) I being now making my new door into the entry,<br />

(Pepys, 1660, Denison 2000)<br />

4.2.4 Semantic developments (Traugott 1989)<br />

Epistemic uses <strong>of</strong> modals have developed from deontic uses. <strong>The</strong> time <strong>of</strong><br />

emergence varies. Sculan ‘shall, should’ is used as an evidential marker in Old<br />

<strong>English</strong>. Must and will in strongly epistemtic uses are much later:<br />

(42) a. <strong>The</strong> fruit muste be delicious, the tree being so beautiful.<br />

(1623 Middleton, Spanish Gipsie I, i.16, Traugott 1989: 42)<br />

b. This will be your luggage, I suppose.<br />

(1847 Ch. Brontë, Jane Eyre XI, Traugott 1989: 43)<br />

References and further reading<br />

Synchronic aspects<br />

* Huddleston, Rodney, and Pullum, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey K. 2002. <strong>The</strong> Cambridge Grammar<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong> Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1519–43.<br />

7

Butters, Ronald R. 1983. Synt<strong>ac</strong>tic change in British <strong>English</strong> propredicates.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>English</strong> Linguistics 16: 1-8.<br />

Halliday, Michael A. K., and Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1976. Cohesion in <strong>English</strong>. Harlow:<br />

Longman.<br />

Kato, Kazuo, and Butters, Ronald R. 1987. American instances <strong>of</strong> propredicate<br />

do. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>English</strong> Linguistics 20: 212-216.<br />

McCawley, James D. 1998 [1988]. <strong>The</strong> synt<strong>ac</strong>tic phenomena <strong>of</strong> <strong>English</strong>. Chicago:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, chapter 8.<br />

Schütze, Carson T. 2004. Synchronic and di<strong>ac</strong>hronic microvariation in <strong>English</strong> do.<br />

Lingua 114: 495–516.<br />

Di<strong>ac</strong>hronic aspects<br />

Beths, Frank. 1999. <strong>The</strong> history <strong>of</strong> dare and the status <strong>of</strong> unidirectionality.<br />

Linguistics 37: 1069–1110.<br />

Denison, David. 1985. <strong>The</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> periphrastic DO: Ellegård and Visser<br />

reconsidered. In Papers from the 4th International Conference on <strong>English</strong><br />

Historical Linguistics, eds. Roger Eaton, Olga Fischer, Willem Koopman<br />

and Frederike van der Leek. Amsterdam: Benjamins.<br />

Denison, David 1993. <strong>English</strong> Historical Syntax. London: Longman. [Chapter 11]<br />

Denison, David 1998. Syntax. <strong>The</strong> Cambridge history <strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong> language,<br />

vol. 4, 1776-1997, ed. Suzanne Romaine, 92-329. Cambridge: Cambridge<br />

University Press.<br />

Denison, David. 2000. Combining <strong>English</strong> auxiliaries. In Pathways <strong>of</strong> Change:<br />

Grammaticalization in <strong>English</strong>, eds. Olga Fischer, Anette Rosenb<strong>ac</strong>h and<br />

Dieter Stein, 111–147. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Downloadable from<br />

Denison’s website]<br />

Kemenade van, A. 1993. <strong>The</strong> history <strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong> modals: a reanalysis. Folia<br />

Linguistica Historica XIII/1-2:143-66.<br />

Lightfoot, David W. 1979. Principles <strong>of</strong> Di<strong>ac</strong>hronic Syntax. Cambridge:<br />

Cambridge University Press [Chapter 2].<br />

Nagle, S. J. 1989. Quasi-modals, marginal modals, and the di<strong>ac</strong>hrony <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>English</strong> modal auxiliaries. Folia Linguistica Historica 9: 93–104.<br />

Plank, Franz. 1984. <strong>The</strong> modals story retold. Studies in Language 8: 305–64.<br />

Roberts, Ian G. 1985. Agreement parameters and the development <strong>of</strong> <strong>English</strong><br />

modal auxiliaries. Natural Language and Linguistic <strong>The</strong>ory 3:21–58.<br />

Roberts, Ian. 1993. Verbs and Di<strong>ac</strong>hronic syntax. Dordrecht: Kluwer, Chapter 3.<br />

Romaine, Suzanne 1981 <strong>The</strong> transparency principle: what it is and why it doesn’t<br />

work. Lingua 55: 277-300.<br />

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 1989. On the rise <strong>of</strong> epistemic meanings in <strong>English</strong>: An<br />

example <strong>of</strong> subjectification in semantic change. Language 65: 31–55.<br />

Warner, Anthony. 1983. Review <strong>of</strong> Lightfoot 1979. Journal <strong>of</strong> Linguistics 19: 187-<br />

209.<br />

Warner, Anthony. 1990. Reworking the history <strong>of</strong> the <strong>English</strong> auxiliaries. In<br />

Papers from the 5th International Conference on <strong>English</strong> Historical<br />

Linguistics, eds. Sylvia Adamson, Vivien Law, Nigel Vincent and Susan<br />

Wright, 537–58. Amsterdam: Benjamins.<br />

8