Theories of L1 Acq. Dr. D. Anderson, U. of Camb. 1 ... - Ling.cam.ac.uk

Theories of L1 Acq. Dr. D. Anderson, U. of Camb. 1 ... - Ling.cam.ac.uk

Theories of L1 Acq. Dr. D. Anderson, U. of Camb. 1 ... - Ling.cam.ac.uk

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

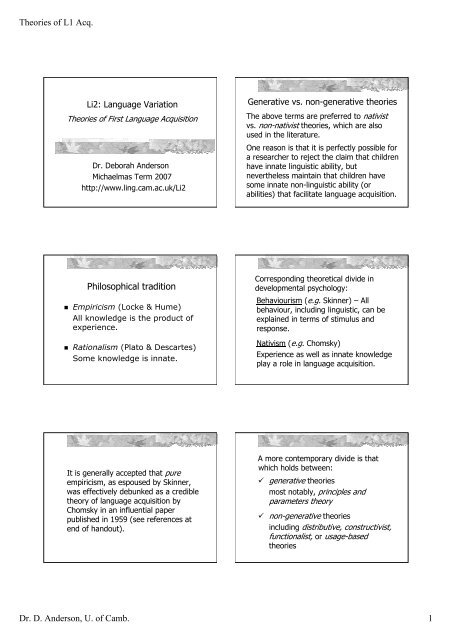

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Li2: Language Variation<br />

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> First Language <strong>Acq</strong>uisition<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. Deborah <strong>Anderson</strong><br />

Michaelmas Term 2007<br />

http://www.ling.<strong>cam</strong>.<strong>ac</strong>.<strong>uk</strong>/Li2<br />

Generative vs. non-generative theories<br />

The above terms are preferred to nativist<br />

vs. non-nativis theories, which are also<br />

used in the literature.<br />

One reason is that it is perfectly possible for<br />

a researcher to reject the claim that children<br />

have innate linguistic ability, but<br />

nevertheless maintain that children have<br />

some innate non-linguistic ability (or<br />

abilities) that f<strong>ac</strong>ilitate language <strong>ac</strong>quisition.<br />

<br />

<br />

Philosophical tradition<br />

Empiricism (Locke & Hume)<br />

All knowledge is the product <strong>of</strong><br />

experience.<br />

Rationalism (Plato & Descartes)<br />

Some knowledge is innate.<br />

Corresponding theoretical divide in<br />

developmental psychology:<br />

Behaviourism (e.g. Skinner) – All<br />

behaviour, including linguistic, can be<br />

explained in terms <strong>of</strong> stimulus and<br />

response.<br />

Nativism (e.g. Chomsky)<br />

Experience as well as innate knowledge<br />

play a role in language <strong>ac</strong>quisition.<br />

It is generally <strong>ac</strong>cepted that pure<br />

empiricism, as espoused by Skinner,<br />

was effectively debunked as a credible<br />

theory <strong>of</strong> language <strong>ac</strong>quisition by<br />

Chomsky in an influential paper<br />

published in 1959 (see references at<br />

end <strong>of</strong> handout).<br />

A more contemporary divide is that<br />

which holds between:<br />

generative theories<br />

most notably, principles and<br />

parameters theory<br />

non-generative theories<br />

including distributive, constructivist,<br />

functionalist, or usage-based<br />

theories<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 1

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

One reasonably reliable means <strong>of</strong><br />

distinguishing the two theoretical <strong>cam</strong>ps<br />

is <strong>ac</strong>cording to whether language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition is viewed as involving the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> language-specific and innately-given<br />

knowledge, which is standardly termed<br />

universal grammar (UG).<br />

As a rule, generative theories<br />

<strong>ac</strong>knowledge the role <strong>of</strong> UG, while nongenerative<br />

theories do not.<br />

Theoretical preliminaries<br />

Two defining char<strong>ac</strong>teristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong><br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition, which any theory <strong>of</strong> language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition must take into <strong>ac</strong>count<br />

(Crain & Lillo-Martin 1999)<br />

Universality: Every normal child <strong>ac</strong>quires<br />

a natural language.<br />

Uniformity: Every language is learned<br />

with equal ease.<br />

The generative appro<strong>ac</strong>h<br />

Two core tenets <strong>of</strong> generative (or<br />

nativist) theory:<br />

<br />

<br />

No negative evidence<br />

Poverty <strong>of</strong> the stimulus<br />

The poverty <strong>of</strong> the stimulus (P.O.S.)<br />

“These, then, are the salient f<strong>ac</strong>ts about language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition or, more properly, language growth.<br />

The child masters a rich system <strong>of</strong> knowledge<br />

without significant instruction and despite a …<br />

deficiency <strong>of</strong> experiential data. The process<br />

involves only a narrow range <strong>of</strong> “errors” or false<br />

hypotheses and takes pl<strong>ac</strong>e rapidly, even<br />

explosively, between two and three years <strong>of</strong> age.<br />

The main question is how children <strong>ac</strong>quire so<br />

much more than they experience.” (italics mine)<br />

Lightfoot (1999:64)<br />

The P.O.S. incorporates two separate<br />

contentions:<br />

1) Language <strong>ac</strong>quisition is <strong>ac</strong>hieved despite<br />

a deficiency <strong>of</strong> data/limited evidence.<br />

The input to the child is not uniformly<br />

grammatical, but contains speech errors,<br />

incomplete sentences, and other<br />

examples <strong>of</strong> ill-formed expressions.<br />

2) Certain linguistic knowledge is <strong>ac</strong>quired<br />

despite a l<strong>ac</strong>k <strong>of</strong> instruction or explicit<br />

evidence for the same.<br />

Example <strong>of</strong> grammatical knowledge the<br />

child <strong>ac</strong>quires which is not taught and<br />

which requires an understanding <strong>of</strong> nonobvious<br />

phrase structure relations:<br />

(1) a. Who do you wanna invite<br />

b. Who do you want to invite<br />

(2) a. When do you wanna go out<br />

b. When do you want to go out<br />

(3) a. *Who do you wanna come<br />

b. Who do you want to come<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 2

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Why is (3a) is grammatically illformed<br />

as compared to the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

the sentences (See Guasti 2002:9)<br />

In generative theory, the focus is thus not<br />

only on the data that can be observed (e.g.<br />

the child’s production <strong>of</strong> well-formed<br />

sentences), but also on aspects <strong>of</strong> the child’s<br />

knowledge that are not directly observable<br />

(e.g. the child’s failure to produce<br />

grammatically ill-formed questions, which<br />

suggests conformance to certain synt<strong>ac</strong>tic<br />

rules <strong>of</strong> English).<br />

(See Pinker 1994:271-3 or <strong>Anderson</strong> & Lightfoot<br />

2002, Chapter 2, for further examples.)<br />

No negative evidence<br />

Negative evidence is neither reliably nor<br />

systematically supplied in the speech to<br />

which the child is exposed (i.e. the PLD<br />

or primary linguistic data)<br />

Furthermore, even when children are<br />

provided with negative evidence, they<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten disregard it.<br />

(Fromkin et al. 2003)<br />

Child: Want other one spoon, Daddy.<br />

Father: You mean you want THE OTHER SPOON<br />

Child: Yes, I want other one spoon, please,<br />

Daddy.<br />

Father: Can you say ‘the other spoon’<br />

Child: Other… one … spoon<br />

Father: Say ‘other.’<br />

Child: Other<br />

Father: Spoon<br />

Child: Spoon<br />

Father: Other… spoon<br />

Child: Other… spoon. Now give me the other one<br />

spoon. (Braine 1971)<br />

Examples from Pinker (1995:119)<br />

Parent:<br />

Child:<br />

Parent:<br />

Child:<br />

Where’s Mommy<br />

Mommy goed to the store.<br />

Mommy goed to the store<br />

No! (annoyed) Daddy, I say<br />

it that way, not you.<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 3

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Child: (a different one): You readed some<br />

<strong>of</strong> it too … she readed all the rest.<br />

Parent: She read the whole thing to you,<br />

huh<br />

Child: Nu-uh, you read some.<br />

Parent: No, that’s right. I readed the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> it.<br />

Child: Readed (annoyed surprise) Read!<br />

(pronounced ‘red’)<br />

Parent: Oh, yeah. Read.<br />

Child: Will you stop that, Papa<br />

For the aforementioned reasons,<br />

then, it is claimed in the generative<br />

literature that provision <strong>of</strong> negative<br />

evidence is neither required nor<br />

sufficient for the successful<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition <strong>of</strong> a first language.<br />

Principle and parameters (P&P) theory<br />

(Chomsky 1981;1986)<br />

In the P&P model <strong>of</strong> language <strong>ac</strong>quisition,<br />

universal principles constrain the basic<br />

form <strong>of</strong> any grammar, while parameters<br />

specify limited and pre-determined ways in<br />

which the grammars <strong>of</strong> individual<br />

languages may vary.<br />

According to the theory, both types <strong>of</strong><br />

information are specified as part <strong>of</strong><br />

universal grammar (UG), an innate,<br />

biologically-specified mental f<strong>ac</strong>ulty that<br />

strongly directs the course <strong>of</strong> language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition.<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> UG principles (Pinker 1994;1995)<br />

Children are born with innate knowledge <strong>of</strong><br />

the existence <strong>of</strong>:<br />

(1) synt<strong>ac</strong>tic categories (e.g. noun, sentence)<br />

(2) grammatical functions (e.g. subject,<br />

object)<br />

(3) grammatical features (e.g.tense, number)<br />

(4) case features (e.g. nominative, absolutive)<br />

(5) phrase structure configurations (i.e. X-bar<br />

theory or phrase tree structures)<br />

The child’s task therefore is simply to<br />

identify how these grammatical<br />

elements are expressed in the<br />

particular language he/she is learning,<br />

(e.g. English, Turkish, Chinese, etc.)<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 4

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Example <strong>of</strong> a UG parameter<br />

Head/directionality parameter, which<br />

specifies that languages may vary in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> whether the heads <strong>of</strong> phrases<br />

(e.g. verbs) take their complements to<br />

the left or to the right (cf. John hit the<br />

girl vs. John the girl hit).<br />

Children <strong>ac</strong>quiring English must adopt<br />

the [+ initial] value <strong>of</strong> this parameter,<br />

while children <strong>ac</strong>quiring Japanese, in<br />

which heads take their complements to<br />

the left, must adopt the negative value,<br />

[- initial]. (see Goodluck 1991)<br />

Supportive evidence for P&P Theory<br />

A. Children’s early sensitivity<br />

to the synt<strong>ac</strong>tic properties<br />

<strong>of</strong> speech<br />

Preferential Looking Paradigm (Hirsh-Pasek & Golink<strong>of</strong>f 1996)<br />

Hirsh-Pasek and Golink<strong>of</strong>f (1996)<br />

14-month-old infants hear the sentence<br />

Hey! She’s kissing the keys! Subjects<br />

looked longer at the screen depicting a<br />

woman kissing some keys while holding<br />

a ball, than at the screen depicting a<br />

woman kissing a ball while holding<br />

some keys.<br />

This would seem to demonstrate, at<br />

the very least, that infants are<br />

sensitive to the grouping <strong>of</strong> basic<br />

sentential constituents.<br />

(But see Tomasello 2003:127-32 for<br />

an dissenting view).<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 5

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

More supportive evidence<br />

B. Creoles<br />

Kegl et al. (1999) – Creolization <strong>of</strong> a<br />

sign-language pidgin by deaf<br />

Nicaraguan children, who were raised<br />

by non-signing parents.<br />

Bickerton (1988) – The Bioprogram<br />

Hypothesis. Advanced to explain striking<br />

similarities in the grammatical properties<br />

<strong>of</strong> creoles throughout the world.<br />

See also Newport’s (1999) discussion <strong>of</strong><br />

children <strong>ac</strong>quiring sign languages (e.g.<br />

Simon).<br />

C. Cases <strong>of</strong> dissociation between<br />

general cognitive ability and linguistic<br />

performance<br />

• Laura (Yamada 1990)<br />

• Christopher (Smith and Tsimpli 1995)<br />

• William’s syndrome<br />

• SLI (Specific Language Impairment)<br />

The non-generative appro<strong>ac</strong>h<br />

As earlier noted, non-generative<br />

theories are in<strong>ac</strong>curately described as<br />

purely empiricist since even nongenerative<br />

researchers <strong>ac</strong>cept that<br />

certain biological f<strong>ac</strong>tors influence<br />

cognitive – and, therefore, linguistic –<br />

development.<br />

All such researchers, however, reject<br />

the generative notion <strong>of</strong> an innately<br />

specified, language-specific<br />

module/f<strong>ac</strong>ulty that guides language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition.<br />

“In usage-based appro<strong>ac</strong>hes,<br />

contentless rules, principles,<br />

parameters, constraints, features, and<br />

so forth are the formal devices <strong>of</strong><br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional linguists; they simply do<br />

not exist in the minds <strong>of</strong> speakers <strong>of</strong> a<br />

natural language.”<br />

Tomasello (2003:100)<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 6

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Core tenets <strong>of</strong> non-generative theory<br />

<br />

<br />

Language is <strong>ac</strong>quired through the<br />

application <strong>of</strong> general learning<br />

strategies and not language-specific<br />

ones.<br />

The communicative function <strong>of</strong><br />

language is central, as it is language<br />

use that dictates the form <strong>of</strong> the<br />

knowledge that the learner <strong>ac</strong>quires.<br />

<br />

The developmental course <strong>of</strong><br />

language <strong>ac</strong>quisition is subject to<br />

variation <strong>ac</strong>cording to differences<br />

in individual ability/individual<br />

experience/grammatical<br />

properties <strong>of</strong> various languages.<br />

Cognitive Functional Appro<strong>ac</strong>h<br />

(Tomasello 2000, 2001, 2003)<br />

Two fundamental abilities underlie <strong>ac</strong>quisition<br />

<strong>of</strong> a first language:<br />

1. intention-reading (i.e. theory <strong>of</strong> mind)<br />

incorporates shared attention, direction <strong>of</strong><br />

attention and imitation<br />

2. pattern-finding<br />

incorporates categorisation, distributional<br />

analysis, and making analogies<br />

Central claim: Children’s early linguistic<br />

competence is item-based: abstr<strong>ac</strong>t<br />

synt<strong>ac</strong>tic categories and ‘schemas’ emerge<br />

gradually and in piecemeal fashion.<br />

Tomasello’s (1992) diary study <strong>of</strong> his own<br />

daughter’s linguistic development during<br />

her second year revealed that her use <strong>of</strong><br />

verbs was considerably restricted compared<br />

to adult-like use <strong>of</strong> the same items.<br />

At the same stage <strong>of</strong> development, his<br />

daughter used semantically similar verbs<br />

in very distinct ways:<br />

cut (X) – Sole usage <strong>of</strong> this verb<br />

vs.<br />

wider use <strong>of</strong> the verb draw:<br />

draw (W) ; draw (W) on (X); draw (W)<br />

for (Y); draw on (Z)<br />

For draw:<br />

“draw-er” (vs. subject)<br />

“thing drawn” (vs. object)<br />

“thing drawn with” (vs. instrument)<br />

For cut:<br />

“thing cut” (vs. object)<br />

No evidence that argument structure <strong>of</strong><br />

cut includes a subject or an instrument,<br />

so no evidence yet for generalization <strong>of</strong><br />

these notions.<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 7

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Additionally:<br />

• Morphological marking (e.g. past<br />

tense) was uneven <strong>ac</strong>ross individual<br />

verbs.<br />

• The best predictor <strong>of</strong> her verb usage<br />

the next day was not her use <strong>of</strong><br />

other verbs but rather her use <strong>of</strong><br />

the same verb. Changes were<br />

conservative, typically involving only<br />

a small addition or modification.<br />

Some item-based schemas <strong>of</strong> a 24-month-old child<br />

(Tomasello 2003:120)<br />

Other item-based patterns in linguistic<br />

development:<br />

Rubino & Pine (1998) – Studied 3-<br />

yr-old child learning Brazilian<br />

Portuguese. Child produced adultlike<br />

subject-verb agreement only for<br />

those verbs that occurred with high<br />

frequency in the adult language<br />

(e.g. 1 st person singular).<br />

Berman & Armon-Lotem (1995) –<br />

Studied children <strong>ac</strong>quiring Hebrew.<br />

First 20 verb forms were nearly all<br />

morphologically unanalyzed,<br />

suggesting rote-learning alone.<br />

Notably, the cognitive-functional<br />

<strong>ac</strong>count strongly predicts individual<br />

variation in language development, in<br />

contrast to generative theories which<br />

typically emphasize developmental<br />

uniformity <strong>ac</strong>ross individuals.<br />

Reading Recommendations<br />

Generative (or nativist) theories <strong>of</strong> first language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition<br />

Crain, S. and D. Lillo Martin. 1999. An Introduction<br />

to <strong>Ling</strong>uistic Theory and Language <strong>Acq</strong>uisition.<br />

Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell. (Part I, pp. 1-70, is highly recommended.)<br />

<strong>Anderson</strong>, S. and D. Lightfoot. 2002. The Language<br />

Organ: <strong>Ling</strong>uistics as Cognitive Physiology. CUP.<br />

(Chapter 2 <strong>of</strong>fers examples <strong>of</strong> potential violations <strong>of</strong> UG<br />

constraints that are not attested in child language.)<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 8

<strong>Theories</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>L1</strong> <strong>Acq</strong>.<br />

Pinker, S. 1995. ‘Language <strong>ac</strong>quisition’ in L.<br />

Gleitman, L. & M. Liberman (eds.) Language: An<br />

Invitation to Cognitive Science. 2 nd ed. Vol. 1: 135-<br />

182.<br />

Gleitman, L. & E. Newport, 1995. ‘The invention <strong>of</strong><br />

language by children’ in L. Gleitman & M. Liberman<br />

(eds.) Language: An Invitation to Cognitive Science.<br />

2 nd ed. Vol. 1: 1-24. MIT Press. (Contains a<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> blind children’s <strong>ac</strong>quisition <strong>of</strong> language.)<br />

Guasti, M.T. 2002. Language <strong>Acq</strong>uisition: The<br />

Growth <strong>of</strong> Grammar. MIT Press. (An advanced<br />

source)<br />

J<strong>ac</strong>kend<strong>of</strong>f, R. 2002. Foundations <strong>of</strong> Language:<br />

Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution. OUP. (See<br />

especially Chapter 4, Universal Grammar, where<br />

standard arguments against generative theory are<br />

reviewed and refuted.)<br />

Lust, B. and C. Foley. 2004. First Language<br />

<strong>Acq</strong>uisition: The Essential Readings. Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell.<br />

(Contains reprints <strong>of</strong> important papers, including Chomsky<br />

1959, Lenneberg 1967 and Brown 1973.)<br />

Russell, J. 2004. What is Language Development:<br />

Rationalist, Empiricist and Pragmatist Appro<strong>ac</strong>hes to<br />

the <strong>Acq</strong>uisition <strong>of</strong> Syntax. OUP.<br />

Non-generative (or non-nativist) theories <strong>of</strong><br />

language <strong>ac</strong>quisition<br />

Tomasello, M. 2003. Constructing a Language: A<br />

Usage-Based Theory <strong>of</strong> Language <strong>Acq</strong>uisition.<br />

Harvard University Press. (Chapter 4, ‘Early synt<strong>ac</strong>tic<br />

constructions’, is highly recommended.)<br />

Clark, E. 2002. First Language <strong>Acq</strong>uisition. CUP.<br />

(Chapter 7, ‘First combinations, first constructions’)<br />

Tomasello, M. 2001. ‘The item-based nature <strong>of</strong><br />

children’s early synt<strong>ac</strong>tic development.’ In M.<br />

Tomasello and E. Bates (eds.) Language<br />

Development: Essential Readings. Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell.<br />

Slobin, D. 2001. ‘Form/function relations: How<br />

do children find out what they are’ In M.<br />

Tomasello and E. Bates (eds.) Language<br />

Development: Essential Readings. Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell.<br />

Snow, C.E. 1999. ‘Social perspectives on the<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> language’ in M<strong>ac</strong>Whinney, B (ed.)<br />

The Emergence <strong>of</strong> Language. Lawrence Erlbaum.<br />

Elman, J. 2001. ‘Connectionism and language<br />

<strong>ac</strong>quisition.’ In M. Tomasello and E. Bates (eds.)<br />

Language Development: Essential Readings.<br />

Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell. (A short introductory level paper.)<br />

Elman, J. 1999. ‘The emergence <strong>of</strong> language: A<br />

consipir<strong>ac</strong>y theory’ in B. M<strong>ac</strong>Whinney (ed.) The<br />

Emergence <strong>of</strong> Language. Lawrence Erlbaum.<br />

(Examines the issue <strong>of</strong> innateness from a<br />

neurophysiological perspective.)<br />

Tomasello, M. 2000. ‘Do young children have adult<br />

synt<strong>ac</strong>tic competence’ Cognition 74: 209-53.<br />

Other sources<br />

Bickerton, D. 1988. ‘Creole languages and the<br />

bioprogram.’ In Newmeyer, F.J. (ed.) <strong>Ling</strong>uistics: the<br />

<strong>Camb</strong>ridge Survey. Vol. 2: <strong>Ling</strong>uistic Theory,<br />

Extensions and Implications. CUP.<br />

Kegl, J., A. Senghas, and M. Coppola. 1999. ‘Creation<br />

through cont<strong>ac</strong>t’ in M. DeGraff (ed.) Language Creation and<br />

Language Change: Creolization, Di<strong>ac</strong>hrony and<br />

Development. MIT Press.<br />

Yamada, J. 1990. Laura: A Case Study for the Modularity <strong>of</strong><br />

Language. MIT Press.<br />

Smith, N. & I. Tsimpli. 1995. The Mind <strong>of</strong> a Savant:<br />

Language Learning and Modularity. Bl<strong>ac</strong>kwell. (Discussion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the linguistic savant Christopher.)<br />

Newport, E. 1999. ‘Reduced input in the <strong>ac</strong>quisition <strong>of</strong><br />

signed languages’ in M. DeGraff (ed.) Language Creation<br />

and Language Change: Creolization, Di<strong>ac</strong>hrony and<br />

Development. MIT Press. (Discussion <strong>of</strong> Simon.)<br />

<strong>Dr</strong>. D. <strong>Anderson</strong>, U. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Camb</strong>. 9